Abstract

Three regions of the biphenyl dioxygenase (BDO) of Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 have previously been shown to significantly influence the interaction between enzyme and substrates at the active site. For a further discrimination within these regions, we investigated the effects of 23 individual amino acid exchanges. The regiospecificity of substrate dioxygenation was used as a sensitive means to monitor changes in the steric-electronic structure of the active site. Replacements of residues that, according to a model of the BDO three-dimensional structure, directly interact with substrates in most, but not all, cases (Met231, Phe378, and Phe384) very strongly altered this parameter (by factors of >7). On the other hand, a number of amino acids (Ile243, Ile326, Phe332, Pro334, and Trp392) which have no contacts with substrates also strongly changed the site preference of dioxygenation (by factors of between 2.6 and 3.5). This demonstrates that residues which had not been predicted to be influential can play a pivotal role in BDO specificity.

Aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases (ARHDOs) are key enzymes of the aerobic bacterial metabolism of aromatic compounds (3, 4). This family of enzymes is of increasing interest due to the range of substrates that it is able to accept and the variety of reactions that it can catalyze (3, 21). Applications range from the breakdown of environmental pollutants (4, 7) to the stereospecific synthesis of chiral synthons (3, 12). For a better understanding of substrate acceptance by ARHDOs, the identification of crucial amino acid (AA) residues at the active site is of major importance. The only three-dimensional structure of an ARHDO that has been solved to date is that of a class III enzyme preferentially accepting naphthalene (5, 13, 14). The influences of a number of single and multiple AA exchanges on substrate oxidation have been investigated with this enzyme as well as with class II biphenyl, toluene, and chlorobenzene dioxygenases (1, 6, 15, 18, 19, 20, 28). In the case of biphenyl dioxygenases (BDOs), these studies led to the identification of three regions of the α subunit (BphA1) that crucially influence the interaction with substrates at the active site. According to the X-ray crystal structure of the naphthalene dioxygenase (NDO), the majority of residues that form the substrate-binding site appear to be located within or close to these segments. The influence of most AAs in these three regions on the interaction with substrates is still unknown. We therefore undertook an investigation of 23 such residues of a broad-substrate-range BDO. Among these residues, 15 had not previously been examined in any ARHDO.

Construction of mutant α subunit genes.

Mutations were introduced into the bphA1 gene of Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 (2, 10) as follows. With appropriate mutagenic primers, two overlapping DNA fragments which contained a given mutation were synthesized by PCR (22). Subsequently, these two fragments were joined by overlap extension PCR (9). By using established procedures (24), the resulting products were cleaved with restriction enzymes and ligated into identically cleaved and dephosphorylated pAIA100, a recombinant expression vector harboring the four genes of the BDO system, bphA1mA2A3A4 (bphA1m contains silent mutations that introduce additional restriction sites), downstream of a phage T7 late promoter (28). After cloning, the integrity of all PCR-synthesized fragments was verified by DNA sequencing (11). The names of the resulting plasmids and the respective AA exchanges are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Activity toward biphenyl and regiospecificity of CB dioxygenation of WT and variant BDOs

| Name of plasmid construct | AA exchange in BphA1 | Activity with biphenyl [mA434/OD600·min)]a | % of dioxygenation productb derived from:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,3′-CB

|

3,4′-CB

|

||||||||

| Product 1 (4′,5′-dioxygenatedc) | Product 2 (5,6-dioxygenatedc) | Product 3 (5′,6′-dioxygenatedd) | Product 4 (2,3-dioxygenatede) | Product 1 (4,5-dioxygenatedc) | Product 2 (2′,3′-dioxygenatedc) | Product 3 (5,6-dioxygenatedf) | |||

| pAIA100 | None | 86 ± 8.1 | 8.0 ± 1.9 | 16.7 ± 1.7 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 70.8 ± 2.2 | 12.8 ± 0.8 | 49.8 ± 2.7 | 37.4 ± 2.4 |

| pMZ101 | Ile216Ala | 68 ± 7.9 | 16.6 ± 5.7 | 17.1 ± 6.4 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 60.5 ± 2.1 | 10.6 ± 0.8 | 52.5 ± 2.3 | 36.9 ± 1.5 |

| pMZ102 | Pro217Ala | 81 ± 9.8 | 12.6 ± 4.7 | 13.6 ± 1.7 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 70.2 ± 2.8 | 10.1 ± 0.6 | 56.3 ± 2.7 | 33.6 ± 2.1 |

| pMZ103 | Phe222Ala | 55 ± 5.9 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 14.8 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 75.8 ± 1.0 | 14.9 ± 0.7 | 44.6 ± 1.4 | 40.6 ± 0.7 |

| pMZ104 | Ala223Ser | 41 ± 4.8 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 18.2 ± 1.7 | 3.4 ± 2.0 | 70.7 ± 0.5 | 12.0 ± 1.1 | 54.4 ± 2.5 | 33.5 ± 1.4 |

| pMZ105 | Met231Ala | 28 ± 3.0 | NDg | 12.3 ± 8.3 | 32.1 ± 9.7 | 55.5 ± 1.4 | 58.4 ± 2.4 | ND | 41.6 ± 2.4 |

| pMZ106 | Ala234Ser | 28 ± 3.4 | 15.5 ± 1.5 | 15.1 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 66.2 ± 1.5 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 62.5 ± 0.3 | 32.5 ± 0.2 |

| pMZ107 | Leu240Ala | 112 ± 28 | 11.5 ± 4.5 | 12.9 ± 2.9 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 72.0 ± 1.6 | 15.3 ± 0.2 | 48.3 ± 1.2 | 36.5 ± 1.0 |

| pMZ108 | Ile243Ala | 60 ± 14 | 12.3 ± 2.0 | 17.6 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 65.0 ± 0.8 | 23.0 ± 0.5 | 13.5 ± 0.4 | 63.5 ± 0.5 |

| pMZ109 | Met324Ala | 67 ± 6.9 | 15.1 ± 2.2 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 72.1 ± 1.7 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 52.7 ± 0.9 | 38.0 ± 0.8 |

| pMZ110 | Ile326Ala | 5 ± 1.2 | 13.2 ± 2.1 | 14.4 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 71.7 ± 2.1 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 61.3 ± 1.0 | 28.9 ± 1.3 |

| pMZ111 | Phe332Ala | 21 ± 5.2 | 13.1 ± 1.0 | 18.7 ± 7.7 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 67.4 ± 6.1 | 15.3 ± 0.2 | 50.5 ± 0.6 | 34.2 ± 0.5 |

| pMZ112 | Pro334Ala | 34 ± 4.4 | 21.9 ± 1.1 | 17.9 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 55.1 ± 0.5 | 36.6 ± 0.2 | 20.7 ± 0.5 | 42.7 ± 0.6 |

| pMZ113 | Ile339Ala | 30 ± 5.3 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 15.4 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 76.3 ± 1.2 | 14.6 ± 0.6 | 49.4 ± 1.3 | 36.0 ± 0.6 |

| pMZ114 | Trp342Ala | 30 ± 3.4 | 10.8 ± 1.9 | 11.9 ± 3.2 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 76.1 ± 0.4 | 29.7 ± 2.4 | 27.5 ± 6.2 | 42.9 ± 3.9 |

| pMZ115 | Ile375Ala | 14 ± 2.2 | 7.9 ± 3.2 | 14.4 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 75.2 ± 0.7 | 15.8 ± 0.2 | 51.1 ± 0.9 | 33.1 ± 0.7 |

| pMZ116 | Asn377Ala | 51 ± 9.9 | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 6.5 ± 1.6 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 83.3 ± 1.2 | 23.8 ± 0.1 | 21.5 ± 1.5 | 54.7 ± 1.4 |

| pMZ117 | Phe378Ala | 1 ± 0.3 | ND | 44.8 ± 18.5 | 29.0 ± 14.9 | 26.3 ± 4.5 | 82.1 ± 5.8 | ND | 17.9 ± 3.8 |

| pMZ118 | Ala380Ser | 83 ± 14 | 14.6 ± 7.4 | 13.3 ± 3.1 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 67.5 ± 4.0 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | 52.1 ± 1.3 | 36.1 ± 1.1 |

| pMZ119 | Val383Ser | 21 ± 3.8 | 11.2 ± 2.0 | 7.6 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 79.7 ± 0.9 | 17.6 ± 0.4 | 33.2 ± 1.5 | 49.2 ± 1.2 |

| pMZ120 | Phe384Ala | 3 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 21.3 ± 6.7 | 8.4 ± 5.0 | 67.4 ± 1.2 | 99.2 ± 0.8 | ND | ND |

| pMZ121 | Gly389Ala | 65 ± 1.0 | 22.5 ± 6.7 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 65.1 ± 4.3 | 15.0 ± 1.2 | 46.5 ± 4.7 | 38.5 ± 3.5 |

| pMZ122 | Trp392Ala | 10 ± 1.9 | 13.0 ± 1.1 | 11.6 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 73.2 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 82.0 ± 0.5 | 14.6 ± 0.4 |

| pMZ123 | Val393Ser | 96 ± 19 | 22.3 ± 5.0 | 16.1 ± 3.0 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 56.2 ± 4.3 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 65.5 ± 0.5 | 27.2 ± 0.4 |

mA434, concentration of 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoate determined as absorbance at 434 nm. OD600, concentration of cells, determined as turbidity at 600 nm. Values are means and standard deviations from three individual measurements.

Metabolites were quantitated from high-pressure liquid chromatography peak areas determined at the λmax of the individual metabolite and were normalized to the internal standard (28). The sum of the values for all metabolites formed from a given substrate by a given enzyme represents 100%. Percentages are apparent, as molar extinction coefficients are unknown. Values are means and standard deviations from three individual measurements.

Tentative assignment of dioxygenation based on the observation that typically the WT BDO prefers o, m dioxygenation to m,p dioxygenation.

Assignment of dioxygenation based on comparison with the 5′,6′-dioxygenated metabolite formed by the BDO of Rhodococcus globerulus P6 (M. Seeger, M. Zielinski, and B. Hofer, unpublished results).

Assignment of dioxygenation from reference 8.

Assignment of dioxygenation from reference 17.

ND, not detected.

Concentrations and activities of variants.

Genes were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS) (26). Subsequently, resting cells were prepared and disrupted with a French press as previously described (28). The supernatants obtained by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 45 min were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10). Despite exchanges of only single residues, some of the variants differed in mobilities (not shown). No significant differences were observed in the concentrations of dissolved wild-type (WT) and variant subunits. BDO activities were assayed with resting cells (final optical density at 600 nm, 0.1). They were mixed with resting cells harboring pDD372 (final optical density at 600 nm, 0.2), which contains bphBC (10). The conversion of biphenyl into 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoate was monitored for 60 min as described previously (28). Activities varied between approximately 1 and 130% of the WT value (Table 1). Such differences are not unusual when enzymes are modified at or near the active site. The largest effects were observed with variants Ile326Ala, Phe378Ala, and Phe384Ala. An explanation for the effect of the Ile326Ala exchange is not apparent; however, a model of the BDO structure (see below) suggests that the replacements of the Phe residues decrease the activity by enlarging the substrate-binding pocket. Additionally, Phe378Ala may eliminate a stacking interaction with the biphenyl.

Effects of AA replacements on the structure of the active site.

Two substituted biphenyls, 2,3′- and 3,4′-chlorobiphenyl (CB), are dioxygenated by the WT enzyme at a total of seven different sites (28). Therefore, they were selected as sensitive probes to monitor the effects of individual AA replacements on the steric-electronic structure of the active site. As described previously (28), resting cells were incubated with the CBs, products were quantitated by high-pressure liquid chromatography-UV spectrometry, and their percentages were determined (Table 1). If the percentages for the WT and the variant, after convergence by one standard deviation, still differed by a factor of ≥1.5, 2.5, or 4.0 for at least one of the metabolites, the effects were classified as moderate, strong, or very strong, respectively. Numerical values are given in Fig. 1.

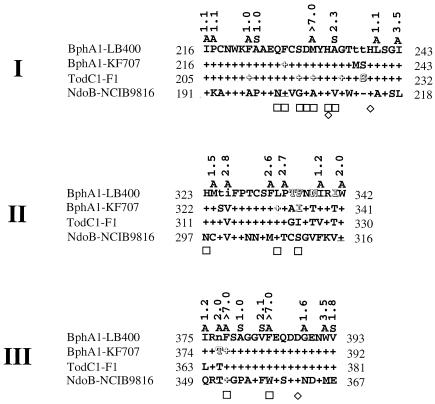

FIG. 1.

Overview of involvement of AAs in ARHDO-substrate interaction. Sequence alignments of segments I to III are shown for four ARHDOs. The positions of the first and last residues are given. The AA exchanges described in the present study and the magnitudes of their effects on the regiospecificity of dioxygenation are indicated above the alignments. Effects of >7.0 were assigned whenever one of the WT metabolites was below the level of detection. +, AA identical to BphA1-LB400; −, gap. The effects of previous AA replacements (1, 6, 15, 18, 19, 20, 27) are symbolized as follows: lowercase letters, no or weak effect; underlined symbol, moderate effect; outlined symbol, strong or very strong effect. The residues that in the NDO structure are part of the substrate-binding site or are ligands of the mononuclear iron (5, 16) are indicated by squares or diamonds, respectively, below the alignments.

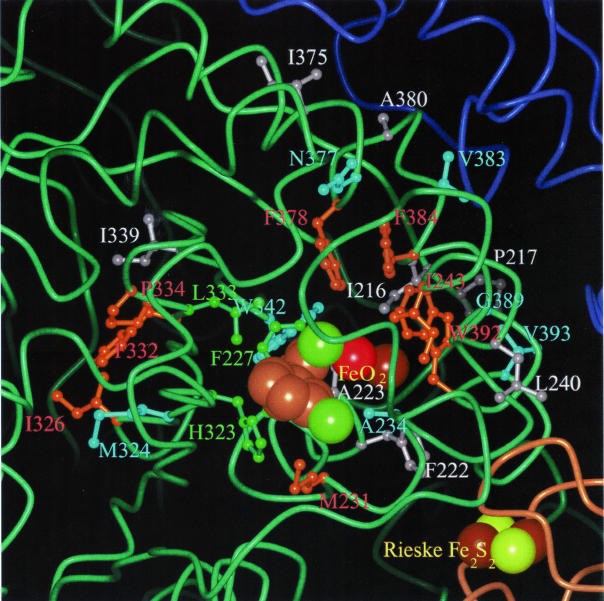

Significant effects of AA exchanges were observed in all three regions. For correlations with the spatial positions of the respective residues, a model of the BDO hydroxylase was derived from NDO crystal structures (5, 14) by using Modeller (23). Restraint parameters were kept at the default values. The root mean square deviation of modeled C-alpha atoms to the template coordinates was 0.5 Å, and no short nonbonded contacts smaller than 2.5 Å occurred. In order to stay as close as possible to the template structure, no additional molecular dynamics calculations were attempted. The dioxygen was positioned side-on relative to the mononuclear iron (13). A ligand molecule, derived by using Sybyl 6.8 (Tripos Inc., St. Louis, Mo.) from a template structure obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (Cambridge, United Kingdom), was placed manually in the active site of the model at the approximate position of the ligand in the NDO structure (Fig. 2). Below, the assignments of functions to specific residues are based on the BDO model.

FIG. 2.

Structural model of a hydroxylase-substrate complex of BDO-LB400 in the region around the catalytic center. A substrate molecule, 2,3′-CB, is shown in the active-site cavity. Main chains of subunits are drawn as tubes. green, α subunit A; brown, α subunit B; blue, β subunit A. The substrate molecule, the Rieske cluster, and the mononuclear iron-dioxygen complex are shown in CPK representation. Light brown, substrate carbons; green, substrate chlorines; yellow, sulfur; dark brown, iron; red, oxygen. AA side chains are shown in ball-and-stick representation. Side chains that were replaced in this work are colored according to the effect of the exchange upon substrate dioxygenation: orange, (very) strong; cyan, moderate; gray, weak. Other substrate-lining side chains that are discussed in the text are in greenish colors. The figure was drawn by using Molscript (16) and rendered with PovRay.

Very strong effects (factors of >7) were observed for the exchanges of three residues (Met231, Phe378, and Phe384) that belong to the substrate-binding pocket (Fig. 2). In contrast, the replacement of Ala234, another substrate-lining residue, resulted in only a 2.3-fold difference from the WT value. On the other hand, significant effects (factors of between 1.5 and 3.5) were also observed for replacements of AAs that do not directly interact with substrate molecules and may be regarded as second-shell residues, i.e., Ile243, Met324, Ile326, Phe 332, Pro334, Trp342, Asn377, Val383, Gly389, Trp392, and Val393 (Fig. 2). In most, although not all, of these cases, the model suggests potential mechanisms. Five of the AAs (Met324, Phe 332, Pro334, Asn377, and Val383) are direct neighbors of substrate-lining residues (His323, Leu333, Phe378, and Phe384, respectively) (Fig. 2). Their replacements most likely influence the spatial positions of the latter and thereby affect the preferred positions of the substrate. Similarly, Ile243Ala and Ile326Ala could transfer their influence through main chain shifts to residues His239 and His323, respectively, which directly interact with the mononuclear iron and the substrate, respectively (Fig. 2). Bulky Trp residues often act as spacers between structural elements. The replacements of Trp342 and Trp392 by the much smaller Ala residues should cause an approach between the β strand or α helix, respectively, carrying these residues and the α helix containing the substrate-binding Phe227 (Fig. 2).

Altogether, eight α subunit positions examined in the present work have previously been investigated in class II and class III ARHDOs. Agreements with the present results are found for five positions, disagreements are found in two cases, and a partial agreement is found in one instance (Fig. 1). This suggests that in most cases the available data should correctly predict whether or not the replacement of a specific residue in another class II or class III ARHDO will influence substrate interaction.

As pointed out above, exchanges of residues that are not in the immediate vicinity of the bound substrate were found to significantly influence the structure of the active site. An importance of such residues has also been observed with other enzymes (25). The medium- or long-range interactions that are responsible for such indirect effects of AA replacements are neither obvious nor currently predictable and are thus of particular interest. A determination of the structure of a respective variant-substrate complex is required for a definite elucidation of the underlying mechanisms. The present results identified a number of candidates for such studies. Moreover, the present study suggests several sensitive positions as key targets for AA replacements that aim at the generation of enzymes with optimized substrate or product specificities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Standfuss-Gabisch and Wera Collisi for help with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis and Michael Seeger for critical reading of the manuscript.

We gratefully acknowledge funding of this work through a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ho 1219/2-1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Beil, S., J. R. Mason, K. N. Timmis, and D. H. Pieper. 1998. Identification of chlorobenzene dioxygenase sequence elements involved in dechlorination of 1,2,4,5-tetrachlorobenzene. J. Bacteriol. 180:5520-5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bopp, L. H. 1986. Degradation of highly chlorinated PCBs by Pseudomonas strain LB400. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1:23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd, D. R., and G. N. Sheldrake. 1998. The dioxygenase-catalyzed formation of vicinal cis-diols. Nat. Prod. Rep. 15:309-325. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler, C. S., and J. R. Mason. 1997. Structure-function analysis of the bacterial aromatic ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 38:47-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carredano, E., A. Karlsson, B. Kauppi, D. Choudhury, R. E. Parales, J. V. Parales, K. Lee, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Ramaswamy. 2000. Substrate binding site of naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase: functional implications of indole binding. J. Mol. Biol. 296:701-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson, B. D., and F. J. Mondello. 1993. Enhanced biodegradation of polychlorinated biphenyls after site-directed mutagenesis of a biphenyl dioxygenase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3858-3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson, D. T., and R. E. Parales. 2000. Aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenases in environmental biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddock, J. D., J. R. Horton, and D. T. Gibson. 1995. Dihydroxylation and dechlorination of chlorinated biphenyls by purified biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. J. Bacteriol. 177:20-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higuchi, R., B. Krummel, and R. K. Saiki. 1988. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:7351-7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofer, B., L. D. Eltis, D. N. Dowling, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Genetic analysis of a Pseudomonas locus encoding a pathway for biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl degradation Gene. 130:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofer, B., S. Backhaus, and K. N. Timmis. 1994. The biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl-degradation locus (bph) of Pseudomonas sp. LB400 encodes four additional metabolic enzymes. Gene 144:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudlicky, T., D. Gonzalez, and D. T. Gibson. 1999. Enzymatic hydroxylation of aromatics in enantioselective synthesis: expanding asymmetric methodology. Aldrichim. Acta 32:35-62. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson, A., J. V. Parales, R. E. Parales, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Ramaswamy. 2003. Crystal structure of naphthalene dioxygenase: side-on binding of dioxygen to iron. Science 299:1039-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kauppi, B., K. Lee, E. Carredano, R. E. Parales, D. T. Gibson, H. Eklund, and S. Ramaswamy. 1998. Structure of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase—naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. Structure 6:571-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura, N., A. Nishi, M. Goto, and K. Furukawa. 1997. Functional analyses of a variety of chimeric dioxygenases constructed from two biphenyl dioxygenases that are similar structurally but different functionally. J. Bacteriol. 179:3936-3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. Molscript: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 24:946-950. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKay, D. B., M. Seeger, M. Zielinski, B. Hofer, and K. N. Timmis. 1997. Heterologous expression of biphenyl dioxygenase-encoding genes from a gram-positive broad-spectrum polychlorinated biphenyl degrader and characterization of chlorobiphenyl oxidation by the gene products. J. Bacteriol. 179:1924-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondello, F. J., M. P. Turcich, J. H. Lobos, and B. D. Erickson. 1997. Identification and modification of biphenyl dioxygenase sequences that determine the specificity of polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3096-3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parales, R. E., K. Lee, S. M. Resnick, H. Jiang, D. J. Lessner, and D. T. Gibson. 2000. Substrate specificity of naphthalene dioxygenase: effect of specific amino acids at the active site of the enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 182:1641-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parales, R. E., S. M. Resnick, C.-L. Yu, D. R. Boyd, N. D. Sharma, and D. T. Gibson. 2000. Regioselectivity and enantioselectivity of naphthalene dioxygenase during arene cis-dihydroxylation: control by phenylalanine 352 in the alpha subunit. J. Bacteriol. 182:5495-5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resnick, S. M., K. Lee, and D. T. Gibson. 1996. Diverse reactions catalyzed by naphthalene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp strain NCIB 9816. J. Ind. Microbiol. 17:438-457. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saiki, R. K., D. H. Gelfand, S. Stoffel, S. J. Scharf, R. Higuchi, G. T. Horn, K. B. Mullis, and H. A. Erlich. 1988. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 239:487-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sali, A., and T. L. Blundell. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraint. J. Mol. Biol. 234:779-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Shimotohno, A., S. Oue, T. Yano, S. Kuramitsu, and H. Kagamiyama. 2001. Demonstration of the importance and usefulness of manipulating non-active-site residues in protein design. J. Biochem. 129:943-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Studier, F. W. 1991. Use of bacteriophage T7 lysozyme to improve an inducible T7 expression system. J. Mol. Biol. 219:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suenaga, H., T. Watanabe, M. Sato, Ngadiman, and K. Furukawa. 2002. Alteration of regiospecificity in biphenyl dioxygenase by active-site engineering. J. Bacteriol. 184:3682-3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zielinski, M., S. Backhaus, and B. Hofer. 2002. The principal determinants for the structure of the substrate-binding pocket are located within a central core of a biphenyl dioxygenase alpha subunit. Microbiology 148:2439-2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]