Abstract

A novel cell wall hydrolase encoded by the murA gene of Listeria monocytogenes is reported here. Mature MurA is a 66-kDa cell surface protein that is recognized by the well-characterized L. monocytogenes-specific monoclonal antibody EM-7G1. MurA displays two characteristic features: (i) an N-terminal domain with homology to muramidases from several gram-positive bacterial species and (ii) four copies of a cell wall-anchoring LysM repeat motif present within its C-terminal domain. Purified recombinant MurA produced in Escherichia coli was confirmed to be an authentic cell wall hydrolase with lytic properties toward cell wall preparations of Micrococcus lysodeikticus. An isogenic mutant with a deletion of murA that lacked the 66-kDa cell wall hydrolase grew as long chains during exponential growth. Complementation of the mutant strain by chromosomal reintegration of the wild-type gene restored expression of this murein hydrolase activity and cell separation levels to those of the wild-type strain. Studies reported herein suggest that the MurA protein is involved in generalized autolysis of L. monocytogenes.

The ability of cell wall hydrolases to hydrolyze the peptidoglycans of their native cell walls is a phenomenon that has been observed during growth of a number of bacterial species, including Listeria monocytogenes (26). These enzymes have been implicated in various biological functions, including cell wall turnover, cell separation, competence for genetic transformation, formation of flagella, sporulation, cell division, and the lytic action of some antibiotics. Autolysins were believed until recently to contribute only indirectly to the pathogenicity of bacteria by facilitating the release of immunologically active cell wall components or toxins (3, 9). However, recent reports have indicated that autolysins such as the invasion-associated protein (Iap, or p60) and the cell wall amidase (Ami) may contribute directly to the pathogenicity of the gram-positive bacterium L. monocytogenes by mediating bacterial adherence (19). This direct correlation with pathogenicity further reinforces the importance of understanding bacterial autolysis. Recent findings suggest that autolysis is not just an unfavorable side effect of the enzymes that control bacterial cell wall synthesis but that it provides some advantage to the organism that is necessary for its survival.

Autolysins are classified according to their specific types of cleavage, e.g., N-acetylmuramidases, N-acetylglucosaminidases, N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidases, endopeptidases, and transglycosylases (27). In a seminal paper on the role of murein hydrolases, researchers revealed by use of an Escherichia coli strain with deletions of seven enzymes exhibiting lytic cell wall activity that transglycolases, amidases, and endopeptidases are required for cell separation following cell division. The strain lacking hydrolases grew in chains comprising up to 100 cells per chain (13). N-Acetylmuramidases are also specifically involved in cell separation in several gram-positive organisms. Loss of the acmA gene from Lactococcus lactis resulted in the organism growing in very long chains (2). One of the two muramidases (muramidase-2) in Enterococcus hirae is believed to facilitate cell separation while acting in conjunction with muramidase-1 in peptidoglycan hydrolysis (8). A mutant of Enterococcus faecalis which contained a disruption of a gene encoding an autolysin was shown to form longer chains (2 to 10 cells per chain) than the wild type (mainly single cells) (21). A similar phenotype of long chain formation was observed with a Streptococcus pneumoniae mutant lacking the LytB protein (7).

L. monocytogenes is a gram-positive facultative anaerobe that is responsible for severe food-borne infections in humans. Following host consumption of listeria-contaminated food, the bacterium is capable of breaching epithelial and endothelial barriers to cause disseminated infection. In its severest forms, listeriosis manifests as a deadly meningoencephalitis and is a common cause of abortions. Thus, the unborn, newborn, immunocompromised, and elderly are most at risk for infection (30).

The iap gene encodes the p60 protein, which has been shown to possess cell wall hydrolase activity in L. monocytogenes. Spontaneously occurring mutants exhibiting deficient expression of p60 show rough colony morphology and form long chains separated by double septa (15). These mutants have reduced virulence in the mouse model of infection and do not invade fibroblasts efficiently (15). The expression of p60 is controlled at the posttranscriptional level (32), although it is not yet known if the regulation of p60 is at the translational or posttranslational level. It was initially thought that p60 was essential for cell viability because iap mutations were always lethal. However, a mutant harboring a transposon inserted within iap has been isolated (1, 31), indicating that other proteins may be able to compensate for the loss of p60 activity.

Previous work using a monoclonal antibody (MAb) (EM-7G1) specific for L. monocytogenes revealed reactivity with a 66-kDa cell surface protein of L. monocytogenes (4, 20). The expression of p66 is variable and appears to be best detected in bacteria grown in rich media (20). Intriguingly, MAb EM-7G1 also cross-reacts with Iap (p60) (see Fig. 4). Examination of the genome sequence of the L. monocytogenes EGDe strain revealed only one potential open reading frame (ORF), denoted lmo2691 (murA), with regionalized homology to p60, that could encode a cell surface protein of approximately 66 kDa. Here we report the cloning and expression of the gene encoding p66 and identify it as a cell wall hydrolase. Studies using an isogenic ΔmurA mutant revealed that MurA in L. monocytogenes is important for cell separation and autolysis of this bacterium.

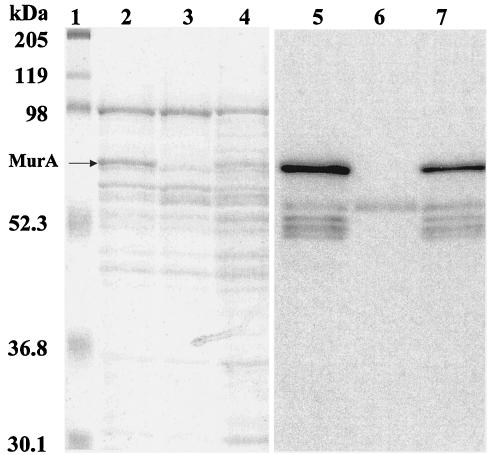

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie blue and immunoblot of MurA from L. monocytogenes EGDe (lanes 2 and 5), isogenic chromosomal deletion mutant ΔmurA (lanes 3 and 6), and complemented ΔmurA attB::murA (lanes 4 and 7). The MAb EM-7G1 was detected via a secondary reaction with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were developed with ECL Western blotting detection reagent. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of prestained SDS marker (Bio-Rad) (lane 1) and MurA are indicated on the left.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, primers, and growth conditions.

L. monocytogenes EGDe was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco) at 37°C. E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) (Difco) at 37°C. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and erythromycin (300 μg/ml for E. coli and 5 μg/ml for L. monocytogenes) were added to broth or agar as needed. When necessary, IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (0.1 mM) and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (20 μg/ml) were spread on agar plates 30 min prior to plating. The strains, plasmids, and primers used for this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this work

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Genotype, description, or sequence | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. monocytogenes | ||

| EGDe 1/2a | Virulent clinical isolate | 12 |

| E. coli | ||

| TOP 10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| BL21 | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 φ80 lacZΔM15 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | |

| DH10β | F′ mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX174 deoR recA1 φaraD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK λ−rpsL endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| XL1-Blue MRF′ Kan | (mcrA)183 (mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn5 (Kanr)] | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEX-6P-1 | GST fusion vector for overexpression of murA | Amersham Biosciences |

| pGEX-6P-1-murA | AprlacIqtac promoter carrying a 1,650-bp PCR fragment of murA | This work |

| pAUL-A | Temperature-sensitive shuttle vector; Emr | 5 |

| pAUL-A-murA | Shuttle vector with flanked murA gene regions | This work |

| pPL2 | L. monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vector | 16 |

| pPL2-murA | Integration vector harboring the murA gene | This work |

| pCR-Script SK+ | pBluescript II SK(+) with a SrfI site incorporated into the polylinker; Apr | Stratagene |

| pCR-XL-TOPO | Shuttle vector for E. coli | Invitrogen |

| Primers | ||

| SC1 | 5′-GAAGTAATCGTTGGATCCGACGAAACAGCGCCTGCTG-3′ | This work |

| SC2 | 5′-GTAGGCTTTTTAGAATTCCTTAATTGTTAATTTCTGACC-3′ | This work |

| SC3 | 5′-ATTGGATCCAACCCGCTCATACAAATA-3′ | This work |

| SC4 | 5′-TTTTTTGCATGCGGCCGCGGTAAGTCACTTCCAATT-3′ | This work |

| SC5 | 5′-TAACAATTAAGCGGCCGCGTGAATGTAAAAAGCCTA-3′ | This work |

| SC6 | 5′-AAGTCTAGAATAGCAACCGTTTGTCTG-3′ | This work |

| SC7 | 5′-CTAAGTAAGCACTTGCTTAT-3′ | This work |

| SC8 | 5′-CTATAATGGGAATTAGATGC-3′ | This work |

DNA isolation and manipulations.

The procedures for the isolation of plasmid and chromosomal DNA from L. monocytogenes were performed as previously described (20). Standard protocols were used for recombinant DNA techniques (23).

Cloning and overexpression.

The gene (murA) encoding the 66-kDa protein was cloned into the glutathione S-transferase (GST) expression vector with primer pairs designed to amplify the murA gene without its signal sequence. The oligonucleotide pair SC1-SC2, incorporating a BamH1 and EcoRI restriction site, respectively, was used to amplify a 1,650-bp PCR fragment of the murA gene for the GST gene fusion system. The amplified fragment was purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit; Qiagen), digested with BamHI and EcoRI, and cloned into the GST gene fusion vector, pGEX-6P-1 (Amersham Biosciences), creating plasmid pGEX-6P-1-murA. The oligonucleotide pair SC1-SC2 was used to verify the sequence of the gene.

The fusion protein was overexpressed by using protocols provided by the vendor of the GST gene fusion system (Amersham Biosciences). The fusion protein was purified from the bacterial lysate by affinity chromatography using glutathione-Sepharose 4FF GSTrap columns. PreScission protease (Amersham Biosciences) was used to remove the GST tag from the recombinant fusion protein. The eluted protein fractions were dialyzed against 1× phosphate-buffered saline, combined, and stored at −20°C for use in further experiments. The fractions from the various steps of the purification process were run on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel and visualized by staining with Coomassie blue.

Detection of proteins by immunoblotting.

The fractions eluted from the glutathione-Sepharose 4FF column were pooled, concentrated, and separated by SDS-12.5% PAGE, after which they were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (28) by use of a semidry transfer cell. Immunoblotting was performed with MAb EM-7G1 (obtained through the courtesy of Michael Johnson, Department of Food Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville) as the primary antibody. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as the secondary antibody. Antibodies bound to the filters were detected by use of ECL Western blotting detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences).

Detection of lytic activity in SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

Procedures for the isolation of cell wall proteins have been previously described (10). Cell wall proteins were obtained from 50-ml cultures grown in BHI broth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0.

Lytic activity was detected by using SDS-12.5% polyacrylamide gels containing 0.2% (wt/vol) autoclaved, lyophilized Micrococcus lysodeikticus ATCC 4698 cells (Sigma) or cell walls of L. monocytogenes EGDe. To allow for protein renaturation after electrophoresis, the gels were gently shaken at room temperature for 24 h, with three to five changes of 100 ml of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7) containing 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Bands of lytic activity were visualized by staining with 1% (wt/vol) methylene blue (Sigma) in 0.01% (wt/vol) KOH and subsequent destaining with distilled water.

Generation of the ΔmurA deletion mutant.

Primers were designed to amplify the flanking regions of the murA gene. The oligonucleotide pair SC3-SC4, containing a NotI restriction site, was used to amplify a 563-bp DNA fragment at the 5′-flanking region of gene murA. The oligonucleotide pair SC5-SC6, containing a NotI restriction site, served to amplify a 520-bp region at the 3′-flanking region of gene murA. The flanking regions were amplified from the chromosome of L. monocytogenes EGDe, digested with NotI, and ligated. The ligation product with the deletion was selectively amplified with oligonucleotide pair SC3-SC6. The PCR product was purified by use of the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), cloned into pCR-Script (Stratagene), and transformed into Epicurian coli XL1-Blue MRF′ Kanr supercompetent cells (Stratagene). Recombinants were identified by blue-white screening. The resulting plasmid was isolated by use of a DNA Qiaquick spin kit (Qiagen). The plasmid DNA and the vector pAUL-A were digested with SacI and XbaI, ligated, and transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells. The recombinants, identified as Lac-negative colonies on erythromycin-containing LB plates (300 μg/ml), were restreaked onto LB-erythromycin (300 μg/ml) plates and screened for the presence of the plasmid by PCR using the SC3-SC6 primer pair. Plasmid DNA of pAUL-A-ΔmurA was isolated from the recombinants and used to transform L. monocytogenes EGDe to generate the chromosomal deletion mutant using previously described methods (24). The presence of the deletion in the murA gene was verified by sequencing.

Complementation of ΔmurA deletion mutant.

The site-specific phage integration vector pPL2 (16) was used for complementation of the ΔmurA mutant. The murA gene and flanking regions were amplified by use of the oligonucleotides SC7 and SC8 and were introduced by the TA cloning method into the vector pCR Topo XL (Invitrogen). The ligation mixture was transformed by electroporation into E. coli DH10β, which was plated onto LB agar plates containing 50 μg of kanamycin per ml. The plasmid was isolated from a murA-harboring recombinant and digested with the restriction endonucleases BamHI and XhoI to release the inserted DNA. Following agarose gel electrophoresis, the murA-harboring fragment was isolated and ligated to BamHI/XhoI-restricted vector pPL2 DNA. Following electroporation of the ligation mixture, recombinant E. coli DH10β clones were plated onto LB agar plates containing 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. One representative recombinant, pPL2::murA, was sequenced to verify the authenticity of the gene cloned and was introduced into the isogenic ΔmurA strain by electroporation. Selection of transformants was performed on BHI agar plates supplemented with 7.5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Insertion of the pPL2::murA plasmid into the PSA bacteriophage attachment site at tRNAArg-attBB′ was verified by using the primer pair NC16-PL95 to specifically amplify a 499-bp PCR product from the integrant strains. Additional primer pair SC1-SC2 was used to specifically detect the murA gene. The complemented strain was examined for expression of the MurA polypeptide and subjected to further phenotypic analysis as described in Results.

Autolysis assay.

Triton X-100-stimulated autolysis in glycine buffer (pH 8.0) was measured as previously described (6). Cells were grown exponentially to an OD620 of 0.3. The culture was then quickly chilled in an ice-ethanol bath, centrifuged (10,000 × g, 4°C, 5 min), and washed once with ice-cold distilled water. The cells were resuspended to an OD620 of 1.0 in 50 mM glycine-0.01% Triton X-100 buffer. Triton X-100-stimulated autolysis was measured during incubation with aeration at 37°C as a decrease in the OD620 by using an Ultrospec III spectrophotometer (Amersham Biosciences).

Penicillin-induced autolysis.

Penicillin-induced autolysis was measured as previously described (21). Bacterial cells from a late-exponential-phase (OD600, 1.0) culture were diluted 1:20 in fresh BHI medium to an OD600 of 0.08 to 0.10. Penicillin G was added to a final concentration of 1.25 μg/ml (10 times the MIC) (18), and the cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking. Aliquots of 1 ml were removed at different time points to measure the OD600.

RESULTS

Database searches for proteins with homology to Listeria p60.

The MAb EM-7G1 recognizes both a 66-kDa protein and the p60 protein in the cell walls of L. monocytogenes EGDe (see Fig. 4). We looked for regional homologies in ORFs from the L. monocytogenes genome sequence to the Iap (p60) protein. The gene identified in the database (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/ListiList) is annotated ORF lmo2691 (murA). The murA nucleotide sequence comprises 1,770 bp and is preceded by a putative ribosome binding site and a possible −10 and −35 region present upstream of the murA gene. An inverted repeat that may function as a transcriptional rho-independent terminator is located downstream, suggesting that it is transcribed as a single gene.

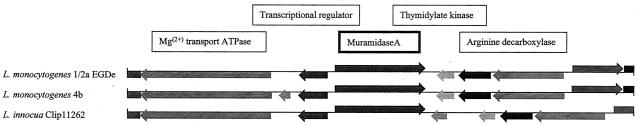

In both L. monocytogenes 4b (http://www.tigr.org) and Listeria innocua CLIP11262, there are corresponding orthologs of murA. Comparison of the regions surrounding murA in L. monocytogenes EGDe, L. monocytogenes 4b, and L. innocua CLIP11262 indicates a conserved genome structure among these three Listeria species (Fig. 1). A divergent reading frame encoding a putative transcriptional regulator (TetR family) with homologies to that of Bacillus subtilis was detected upstream of murA, followed by a Mg2+-dependent transport ATPase. In the region downstream of murA, there are two housekeeping genes, one for a thymidylate kinase followed by one for an arginine decarboxylase. Closer examination of the sequence of L. monocytogenes 4b indicates that a hypothetical ORF resides between the transcriptional regulator and the Mg2+-dependent transport ATPase. In the case of L. innocua CLIP11262, an 818-bp sequence is interposed between murA and the thymidylate kinase gene. A small ORF with some homology to a CTP synthase of Rickettsia prowazekii is present within this inserted sequence.

FIG. 1.

Genome organization of the chromosomal region surrounding the murA gene (lmo2691) in L. monocytogenes strains 1/2a EGDe and 4b and L. innocua CLIP11262. Putative ORFs are represented by filled boxes; murA is displayed with a bold outline. Hypothetical ORFs are shown in gray.

Deduced amino acid sequence and homology comparisons.

It was predicted that murA would encode a protein of 590 amino acids (Fig. 2A), with a deduced molecular mass of 63,571 Da. The first 52 amino acids have all the properties of a gram-positive signal peptide. Cleavage of the scissile bond after residue 52 by a signal peptidase would result in a mature secreted protein of 57,946 Da. Protein database searches showed that the MurA proteins of L. monocytogenes EGDe, L. monocytogenes 4b, and L. innocua CLIP11262 are highly conserved, with 96 and 84% identities at the amino acid level.

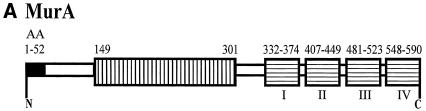

FIG. 2.

MurA sequence. (A) Schematic presentation of the muramidase A protein (MurA) of L. monocytogenes EGDe. The black box indicates the putative signal sequence. The amidase_4 region of the protein is located within the N-terminal amino acids 149 to 301 of the protein. The C-terminal LysM repeats are named I to IV. AA, amino acids. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of repeated carboxy-terminal LysM motifs I to IV of murA plus intervening sequences. CLUSTAL W (1.81) was used for multiple sequence alignment. The consensus sequence proposed by Joris et al. (14) is shown in bold. *, identical amino acids; :, similar amino acids.

A motif comprising the amidase_4 domain (mannosyl glycoprotein endo-beta-N-acetylglucosamidase; accession number PF01832), with conserved catalytic residues glutamic acid (E 216) and aspartic acid (D 242), was located between amino acids 149 and 301 of MurA (Fig. 2A). This finding indicates that MurA is a putative muramidase. BLAST searches with the amidase_4 motif region of MurA revealed additional ORFs in the L. monocytogenes EGDe genome (lmo1076, lmo1215, lmo1216, lmo2203, and lmo2591) that display homology to this domain.

The C-terminal portion of the MurA protein harbors four repeated regions containing a LysM domain (accession number PF01476) (Fig. 2A). The regions are each composed of 43 amino acids (Fig. 2B) separated by intervening sequences that are highly enriched in serine, threonine, and asparagine residues. The overall similarity between the repeated regions was approximately 76%. The C-terminal repeats of MurA had 80% homology to the C-terminal repeated regions of the muramidase-2 of E. hirae as well as homology with the cell wall hydrolases of L. lactis (three LysM repeats) and E. faecalis (five LysM repeats). The C-terminal region also showed homology to two LysM repeat domains in the N-terminal region of the Iap protein of L. monocytogenes. Further searches in the Listeria genome database (12) indicated the presence of other LysM repeat-containing proteins. These include the Iap (p60) protein and other less well-defined ORFs (lmo0880, lmo1303, lmo1941, and lmo2522).

Recombinant GST-MurA fusion proteins are recognized by MAb EM-7G1.

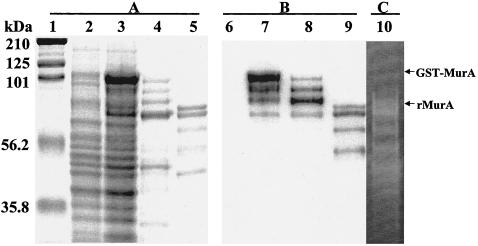

We sought evidence that the cell wall protein recognized by MAb EM-7G1 was indeed MurA. The L. monocytogenes gene (murA) encoding the 66-kDa protein was cloned into the GST expression vector, and its expression was monitored as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 3A, induction of E. coli BL21 recombinants harboring the GST-MurA fusion protein led to the induced expression of an ∼97-kDa polypeptide (cf. lanes 3 and 4). The recombinant ∼97-kDa polypeptide showed specific cross-reactivity in immunoblot studies to the MAb EM-7G1 (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 and 8), indicating that MurA is indeed the listerial gene product recognized by this antibody. The GST-MurA fusion protein was purified directly from the bacterial lysate by using affinity matrix glutathione-Sepharose 4FF GSTrap columns. The fusion protein was eluted under mild, nondenaturing conditions, with glutathione elution buffer used in order to preserve the antigenicity and functionality of the protein. Substantial specific degradation of the GST-MurA fusion occurred during purification. It appeared that the lower-molecular-weight proteins found in the purification of the GST-MurA fusion protein were breakdown products of this protein, because the antibody also showed cross-reactivity to these bands (Fig. 3B, lane 8).

FIG. 3.

Induction and purification of GST-MurA and rMurA. (A) Samples were run on SDS-12.5% PAGE gels and stained with Coomassie blue. (B) Immunoblot of uninduced, induced, and purified GST-MurA and rMurA detected by use of MAb EM-7G1. MAb EM-7G1 was detected via a secondary reaction with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were developed with ECL Western blotting detection reagent. (C) Cell wall hydrolase activity of rMurA detected by SDS-12.5% PAGE after renaturation. The gel contained 0.2% (wt/vol) autoclaved M. lysodeikticus cells. Bands of lytic activity were made visible by alkaline methylene blue staining. Lanes: 1, molecular size marker; 2 and 6, uninduced GST-MurA; 3 and 7, induced GST-MurA; 4 and 8, purified GST-MurA; 5, 9, and 10, purified rMurA. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standard proteins, GST-MurA, and rMurA are indicated.

Purified recombinant MurA (rMurA) devoid of the GST tag was produced by proteolytic cleavage with subsequent purification. Purified rMurA had a molecular weight of ∼72 kDa and was specifically recognized by MAb EM-7G1 (Fig. 3B, lane 9). Cell wall hydrolase activity of rMurA was detected by SDS-12.5% PAGE with 0.2% (wt/vol) M. lysodeikticus autoclaved cells followed by renaturation of the gel (Fig. 3C, lane 10). Specific degradation products of rMurA also exhibited cell wall hydrolase activities (Fig. 3A, lane 5, and Fig. 3C, lane 10). N-terminal amino acid sequencing studies on all of the polypeptide bands seen in Fig. 3A, lane 5, showed that they all had identical N-terminal sequences (data not shown), suggesting that the degradation observed is initiated at the C-terminal end of the molecule and indicating that cell wall hydrolase activity is located within the N-terminal region. The smallest degradation fragment exhibiting hydrolase activity did not cross-react with MAb EM-7G1, suggesting that the epitope recognized is no longer present in this protein fragment.

Construction and analyses of a chromosomal ΔmurA deletion mutant.

To investigate the physiological role of murA, we made a chromosomal in-frame deletion of murA by homologous recombination. After transformation of L. monocytogenes EGDe with the suicide vector pAUL-A-ΔmurA, which carries the flanking sequences of murA, the integrants (Emr) were confirmed by PCR. Subsequently, erythromycin-sensitive colonies were selected and screened for the loss of murA by PCR using the SC3-SC6 primer set. Colonies that produced a PCR product of approximately 1,056 bp were selected for further studies. The mutants were sequenced to show that an internal in-frame deletion of the murA gene had indeed occurred. Several independent mutants were characterized, all of whom had identical characteristics.

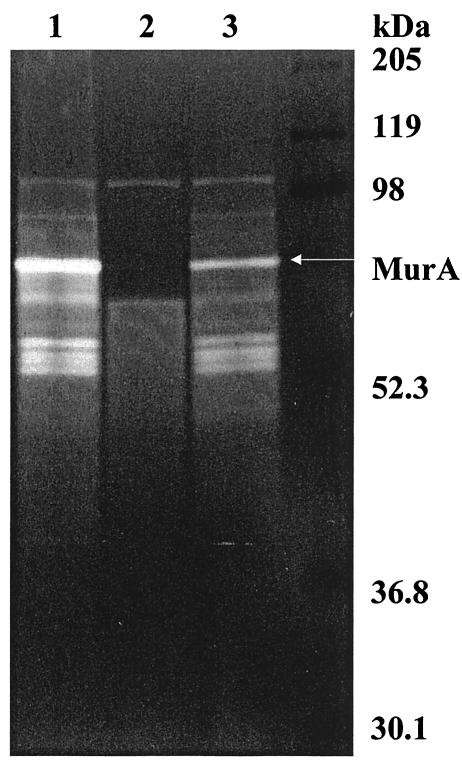

MurA encodes a peptidoglycan hydrolase.

Cell surface proteins of the deletion mutant were isolated, and immunoblot analysis with MAb EM-7G1, the antibody against the 66-kDa cell surface protein, was performed. We also used the bacteriophage integration vector pPL2 to complement the ΔmurA strain by inserting the wild-type gene as a single copy at the PSA bacteriophage attachment site (16). Cell surface proteins from the complemented strain were also used in this analysis. As shown in Fig. 4, the mutant clearly lacked the MurA protein, which was reexpressed in the ΔmurA strain complemented with a chromosomally reinserted murA gene (lanes 5, 6, and 7). This analysis also showed that MurA is a major cell surface protein of L. monocytogenes that is clearly visible following Coomassie staining of cell wall polypeptides after SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4, cf. lanes 2, 3, and 4). In this figure, it is also clear that the MAb EM-7G1 specifically recognizes an epitope common to both MurA and Iap. This is best illustrated in the immunoblot of cell wall proteins of the ΔmurA mutant, in which in the absence of MurA it clearly recognizes the Iap protein (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 6).

Cell surface proteins of L. monocytogenes, its isogenic ΔmurA mutant, and the complemented strain were also analyzed on a renaturing SDS-PAGE gel containing autoclaved M. lysodeikticus cells as a substrate. The clearing band, which represented cell wall hydrolase activity, corresponded to the 66-kDa cell surface protein and was no longer present in the mutant strain but reappeared in the complemented strain (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 3). This band represented one of the major lytic bands present when M. lysodeikticus was used as the substrate. Loss of p66 cell wall hydrolase activity also abolishes the lytic activity of a series of polypeptide species with molecular masses of 52 to 56 kDa, indicating that these are degradation products of p66 MurA. The remaining bands with prominent lytic activity, at 102 and 60 kDa, probably represent activities deriving from the previously described amidase (Ami) and p60 proteins, respectively (20). Comparison of both zymograms (Fig. 3, lane 10, and Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 3) indicated a difference in the autolysis banding pattern for MurA when it was derived either as a recombinant cytosolic protein or as a cell wall protein in L. monocytogenes. These differences are probably the result of the activity of various endo- and exoproteases present in the respective bacterial host strains.

FIG. 5.

Cell wall hydrolase activity of MurA from L. monocytogenes EGDe (lane 1), isogenic deletion mutant ΔmurA (lane 2), and complemented mutant ΔmurA attB::murA (lane 3) detected by SDS-12.5% PAGE after renaturation. The gel contained 0.2% (wt/vol) autoclaved M. lysodeikticus cells. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of standard proteins and MurA are indicated on the right.

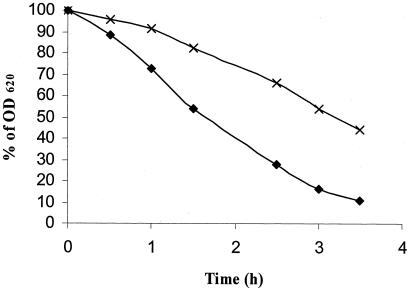

The growth of EGDe ΔmurA was compared to that of the wild type over a range of temperatures (25, 37, and 42°C). The growth of the deletion mutant in BHI broth was similar to that of the wild type at all temperatures, indicating that the cell wall hydrolase was not essential for cell growth. Autolysis of L. monocytogenes EGDe ΔmurA, compared to that of L. monocytogenes EGDe, was considerably diminished and delayed during prolonged stationary-phase growth (data not shown). The mutant was more resistant to Triton X-100-stimulated autolysis (Fig. 6), indicating that p66 is involved in generalized lysis of the host cell. Penicillin-induced cell lysis was determined by the addition of penicillin G to growing cultures. Over a period of 24 h, there was no difference between the wild-type and deletion mutant, as detected by measuring OD600 (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Triton X-100-stimulated autolysis of L. monocytogenes EGDe and EGDe ΔmurA. Autolysis was measured as the decline in optical density. Symbols: ♦, EGDe; ×, EGDe ΔmurA.

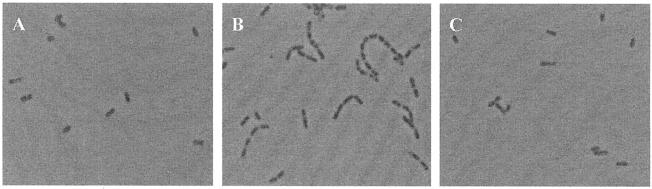

The cells of EGDe and EGDe ΔmurA were also examined by light microscopy when the cultures reached an OD600 of 0.5. EGDe ΔmurA formed longer chains than EGDe, which gave mostly single cells (Fig. 7). Seventy-three percent of EGDe ΔmurA cells were arranged in chains of 3 to 12 bacteria compared to no chains seen with the wild-type strain. The data imply the involvement of p66 in cell separation. However, during stationary-phase growth, the cells of EGDe ΔmurA did not appear to form as many long chains as during the logarithmic phase, suggesting that other cell wall hydrolases are able to compensate for the loss of p66 in EGDe ΔmurA. The complemented strain showed no growth defects over a wide range of growth temperatures and restored cell separation levels to those seen with the wild-type strain (Fig. 7). When plated on BHI agar, the mutant formed smooth colonies that were indistinguishable from those of the wild-type strain.

FIG. 7.

Light microscopic view of L. monocytogenes EGDe (A), deletion mutant ΔmurA (B), and complemented strain ΔmurA attB::murA (C). The pictures were taken at an OD600 of 0.5. Magnification, ×1,000.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified another cell wall hydrolase in L. monocytogenes and characterized the gene, murA, encoding this enzyme. As our studies show, MurA is recognized by the previously well-characterized L. monocytogenes-specific MAb EM-7G1, which recognizes a p66 cell surface protein. Comparative genome analysis of the region surrounding the murA gene shows that this region is highly conserved in the Listeria genus. In the L. monocytogenes EGDe 1/2a, L. monocytogenes 4b, and L. innocua genomes, the murA gene is preceded by a divergently transcribed putative transcriptional regulator. Expression of MurA has been previously shown to be strongly dependent on growth media and other environmental conditions (20). Further studies will be required to examine if the juxtapositioning of these two genes is fortuitous. Intriguingly, although we show here that murA is also present in L. innocua, its expression in this species has not been detected to date (4, 22).

Several distinctive features were apparent from the primary amino acid sequence of MurA. The apparent molecular mass of MurA is larger than would be expected from its primary amino acid sequence, i.e., 66 versus 58 kDa, for the mature protein. Indeed, the purified GST-MurA and rMurA polypeptides had molecular masses that were larger than their theoretical molecular weights (Fig. 4). This feature is not unusual among listerial cell wall proteins (20) and is probably the result of the unusual amino acid composition of the multiple LysM repeats in the protein that must extend through the murein sacculus so that the protein can exhibit its activity.

The N-terminal portion has elements that are similar to amidase_4 domains of muramidases. An overall identity of 35% and similarity of 50% was found between MurA (amino acids 152 to 590) and muramidase-2 of E. hirae (amino acids 64 to 531). MurA (amino acids 57 to 590) also exhibited 33% similarity and 46% identity to the autolysin of E. faecalis (amino acids 89 to 609). An identity of 46% and similarity of 59% was found in the N-terminal region (amino acids 149 to 301) between MurA and muramidase-2, the autolysin of E. faecalis, and AcmA of L. lactis.

In the C terminus of MurA, there are four repeated regions that align with a consensus sequence known as the LysM motif (14). These repeats are similar to those found in several Bacillus lysozymes, the Iap protein of L. monocytogenes, and protein A of Staphylococcus aureus and may recognize a very specific binding site in the peptidoglycan substrate. Other unrelated repeat sequences have been shown to be involved with the binding of pneumococcal autolysins to the cell wall, and the presence of choline in the cell wall teichoic acid is important for this binding (11). It is likely that these highly conserved C-terminal sequence repeats in p66 are also involved in substrate recognition and binding in L. monocytogenes.

In a standardized assay to detect autolytic activity in a renaturing SDS-PAGE gel, several bands exhibiting lysis zones were found in the cell surface fractions of an L. monocytogenes EGDe culture when both M. lysodeikticus and L. monocytogenes cell walls were used as substrates. However, the lytic activities were far more detectable with M. lysodeikticus as a substrate, which is consistent with previous reports obtained using bacterial extracts of L. lactis, Clostridium perfringens, Bacillus megaterium, and E. faecalis (2, 17). One of the lytic bands observed for L. monocytogenes with both substrates corresponded to the 66-kDa cell surface protein that is recognized by MAb EM-7G1. When M. lysodeikticus is used as the substrate, MurA is by far the largest and brightest lytic band in the gel, indicating its role as a major autolysin of L. monocytogenes.

An in-frame L. monocytogenes murA deletion mutant was created in the wild-type background to determine the role of the cell wall hydrolase. The ability to generate this deletion mutation indicates that murA is not an essential gene. L. monocytogenes EGDe ΔmurA, which did not synthesize the 66-kDa cell surface protein, grew in long chains during exponential growth. The aberrant septation phenotype of the deletion strain was overcome in the complemented integrant strain, and the reexpression of the 66-kDa cell wall polypeptide restored murein hydrolase activity resulting from this protein. Interestingly, unlike previously described variants of L. monocytogenes that form chains during logarithmic growth and rough colonies when plated on agar (22, 33), the EGDe ΔmurA strain only forms smooth colonies, with no observable rough colony variants.

Autolysis of L. monocytogenes has been described extensively in a previous study (29) in which five different strains showed autolysis immediately at the end of the exponential growth phase. Cell wall hydrolases are thought to be involved in autolysis of the bacterial cell, and this phenomenon is usually observed after inhibition of further synthesis of peptidoglycan either nutritionally or by the addition of an antibiotic or treatment with certain nonspecific chemicals (26). In this work, we observed that the deletion mutant was more resistant to both prolonged stationary-phase autolysis and Triton X-100-induced autolysis, suggesting that the 66-kDa MurA cell surface protein was involved in generalized autolysis of the host cell.

As do other gram-positive bacteria, L. monocytogenes expresses multiple autolysins, including members of the p60 family such as p60 (iap) (32), p45 (spl) (25), and lmo0394 (12) and members of the amidase (Ami) protein family such as Ami, lmo1215, lmo1216, lmo1521, and lmo2203 (12, 19), which appear to have alternative functions in the organism. The presence of multiple autolysins complicates the process of determining the roles of each autolysin in the organism.

The p60 protein of L. monocytogenes has also been shown to be involved in cell separation (32), and it may be the combination of both enzymes that controls the proper cell separation of this organism. The presence of some single cells in the culture of the deletion mutant as well as the loss of the long chains during stationary-phase growth suggested that Iap (p60) may partially substitute for the function of MurA. The creation of a strain lacking multiple hydrolases could better reveal the exact role of additional proteins such as Ami, p45, and p60 with regard to cell separation in L. monocytogenes. For E. coli, a mutant lacking seven murein hydrolases of different specificities was still viable for growth but could not undergo proper cell separation. In that study, analysis of E. coli mutant strains with various deletions for different combinations of cell wall hydrolases indicated that amidases play the major role in cell separation, followed by transglycosylases and endopeptidase (13).

In conclusion, evidence is presented implicating a role for the p66 protein MurA of L. monocytogenes as a cell wall hydrolase with significant similarities to muramidases present in other related gram-positive microorganisms. MurA appears to be involved in cell separation of the organism, and under times of unfavorable growth conditions it can participate in cell lysis. Regulation governing these two functions is very critical. It must allow for the continuous activity of the enzymes needed for cell wall growth, turnover, and separation while in turn preventing out-of-control hydrolysis of peptidoglycan that can lead to autolysis. Further study of MurA may reveal other roles for this cell wall hydrolase in the physiology of L. monocytogenes.

Acknowledgments

S. A. Carroll and T. Hain contributed equally to this work.

We thank Michael Johnson, University of Arkansas, for the kind gift of monoclonal antibody EM-7G1, Richard Calendar for the gift of plasmid pPL2, Daniela Kaleve and Nelli Schklarenko for excellent technical assistance, and Sonja Otten and Yossi Paitan for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Programm “Proteomik” to T.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bielecki, J. 1994. Insertions within iap gene of Listeria monocytogenes generated by plasmid pLIV are not lethal. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 43:133-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buist, G., J. Kok, K. J. Leenhouts, M. Dabrowska, G. Venema, and A. J. Haandrikman. 1995. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the major peptidoglycan hydrolase of Lactococcus lactis, a muramidase needed for cell separation. J. Bacteriol. 177:1554-1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canvin, J. R., A. P. Marvin, M. Sivakumaran, J. C. Paton, G. J. Boulnois, P. W. Andrew, and T. J. Mitchell. 1995. The role of pneumolysin and autolysin in the pathology of pneumonia and septicemia in mice infected with a type 2 pneumococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 172:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll, S. A. 2001. Ph.D. thesis. University of Maryland, College Park.

- 5.Chakraborty, T., M. Leimeister-Wachter, E. Domann, M. Hartl, W. Goebel, T. Nichterlein, and S. Notermans. 1992. Coordinate regulation of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes requires the product of the prfA gene. J. Bacteriol. 174:568-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jonge, B. L., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 1991. Suppression of autolysis and cell wall turnover in heterogeneous Tn551 mutants of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. J. Bacteriol. 173:1105-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Las, R. B., J. L. Garcia, R. Lopez, and P. Garcia. 2002. Purification and polar localization of pneumococcal LytB, a putative endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase: the chain-dispersing murein hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 184:4988-5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Mar, L. M., R. Fontana, and M. Solioz. 1995. Identification of a gene (arpU) controlling muramidase-2 export in Enterococcus hirae. J. Bacteriol. 177:5912-5917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz, E., R. Lopez, and J. L. Garcia. 1992. Role of the major pneumococcal autolysin in the atypical response of a clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 174:5508-5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domann, E., S. Zechel, A. Lingnau, T. Hain, A. Darji, T. Nichterlein, J. Wehland, and T. Chakraborty. 1997. Identification and characterization of a novel PrfA-regulated gene in Listeria monocytogenes whose product, IrpA, is highly homologous to internalin proteins, which contain leucine-rich repeats. Infect. Immun. 65:101-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia, P., J. L. Garcia, E. Garcia, J. M. Sanchez-Puelles, and R. Lopez. 1990. Modular organization of the lytic enzymes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. Gene 86:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. G. Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidrich, C., A. Ursinus, J. Berger, H. Schwarz, and J. V. Holtje. 2002. Effects of multiple deletions of murein hydrolases on viability, septum cleavage, and sensitivity to large toxic molecules in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:6093-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joris, B., S. Englebert, C. P. Chu, R. Kariyama, L. Daneo-Moore, G. D. Shockman, and J. M. Ghuysen. 1992. Modular design of the Enterococcus hirae muramidase-2 and Streptococcus faecalis autolysin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 70:257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn, M., and W. Goebel. 1989. Identification of an extracellular protein of Listeria monocytogenes possibly involved in intracellular uptake by mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 57:55-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauer, P., M. Y. Chow, M. J. Loessner, D. A. Portnoy, and R. Calendar. 2002. Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. J. Bacteriol. 184:4177-4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leclerc, D., and A. Asselin. 1989. Detection of bacterial cell wall hydrolases after denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Can. J. Microbiol. 35:749-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlan, A. M., and S. J. Foster. 1998. Molecular characterization of an autolytic amidase of Listeria monocytogenes EGD. Microbiology 144:1359-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milohanic, E., R. Jonquieres, P. Cossart, P. Berche, and J. L. Gaillard. 2001. The autolysin Ami contributes to the adhesion of Listeria monocytogenes to eukaryotic cells via its cell wall anchor. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1212-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nannapaneni, R., R. Story, A. K. Bhunia, and M. G. Johnson. 1998. Unstable expression and thermal instability of a species-specific cell surface epitope associated with a 66-kilodalton antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody EM-7G1 within serotypes of Listeria monocytogenes grown in nonselective and selective broths. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3070-3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin, X., K. V. Singh, Y. Xu, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 1998. Effect of disruption of a gene encoding an autolysin of Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2883-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowan, N. J., J. G. Anderson, and A. A. Candlish. 2000. Cellular morphology of rough forms of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from clinical and food samples. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 31:319-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Schaferkordt, S., and T. Chakraborty. 1995. Vector plasmid for insertional mutagenesis and directional cloning in Listeria spp. BioTechniques 19:720-725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schubert, K., A. M. Bichlmaier, E. Mager, K. Wolff, G. Ruhland, and F. Fiedler. 2000. P45, an extracellular 45 kDa protein of Listeria monocytogenes with similarity to protein p60 and exhibiting peptidoglycan lytic activity. Arch. Microbiol. 173:21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shockman, G. D., and J. V. Holtje. 1994. Microbial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases, p. 131-166. In J. M. Ghuysen and R. Hakenbeck (ed.), Bacterial cell wall. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 27.Tomasz, A. 1984. Building and breaking of bonds in the cell wall of bacteria—the role for autolysins, p. 3-12. In C. Nombela (ed.), Microbial cell wall synthesis and autolysis. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 28.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyrrell, E. A. 1973. Autolysis of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 113:1046-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vazquez-Boland, J. A., M. Kuhn, P. Berche, T. Chakraborty, G. Dominguez-Bernal, W. Goebel, B. Gonzalez-Zorn, J. Wehland, and J. Kreft. 2001. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:584-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wisniewski, J. M., and J. E. Bielecki. 1999. Intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes insertional mutant deprived of protein p60. Acta Microbiol. Pol. 48:317-329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wuenscher, M. D., S. Kohler, A. Bubert, U. Gerike, and W. Goebel. 1993. The iap gene of Listeria monocytogenes is essential for cell viability, and its gene product, p60, has bacteriolytic activity. J. Bacteriol. 175:3491-3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zachar, Z., and D. C. Savage. 1979. Microbial interference and colonization of the murine gastrointestinal tract by Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 23:168-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]