Abstract

Migration of an implantable port catheter tip is one of the well-known complications of this procedure, but the etiology of this problem is not clear. We describe here a case of migration of the tip of a port catheter from the right atrium to the right axillary vein in a patient with severe cough. Coughing was suggested for this case as the cause of the catheter tip migration. We corrected the position of the catheter tip via transfemoral snaring.

Keywords: Catheters and catheterization, complications; Veins, interventional procedure; Chemoport

Implantable port catheters are widely used for the patients who need long-term chemotherapy. Migration of the tip of an implantable port catheter is not an uncommon event and the mechanism for this is not clear. Increased intrathoracic pressure due to coughing, sneezing or weight lifting, changing the body position or physical movements such as abduction or adduction of the arms are thought to be the cause of such migration (1). We present here a case of a patient with a port catheter tip that migrated into the right axillary vein; repositioning the catheter tip was done via transfemoral snaring. After repositioning the tip, we observed lateral bending of the upper one third of the catheter towards the right subclavian vein while the patient was coughing.

CASE REPORT

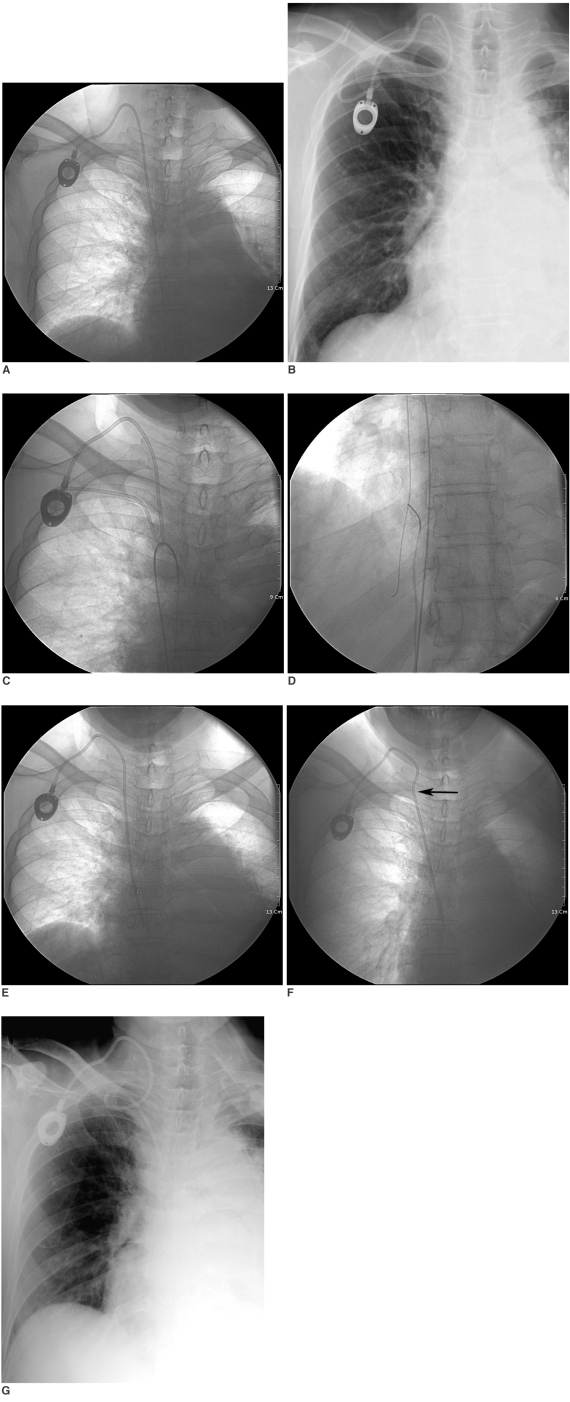

A 64-year-old man with squamous cell lung cancer (T4N2M0, stage IIIb) had an 8-Fr port device catheter (Healthport, Baxter Healthcare Co., McGaw Park, IL) implanted via the right jugular vein under radiologic intervention for administering his monthly chemotherapy. After the implantation, the catheter tip was well-placed at the right atrium, as was noted with on chest radiography with the patient in the supine position (Fig. 1A). Four days after the procedure, the chest posteroanterior radiograph showed migration of the catheter tip with coiling into the right axillary vein, but the location of the port was not changed (Fig. 1B). The patient was in a state of remission and he usually rested in bed without strenuous exercise, yet the patient had a severe cough during this period. On the next day, we tried to reposition the tip of the port catheter. Two punctures were made in the right femoral vein. A 5-Fr pigtail catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) was inserted, via the first puncture site, with a 0.035-inch guide wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). The 5-Fr pigtail catheter was advanced to the right subclavian vein to hook the migrated catheter. The guide wire was directed backward to the inferior vena cava (IVC) (Fig. 1C). A gooseneck snare wire (C.R. Bard, Inc, Murray Hill, NJ) with a cobra catheter (Cook, Bloomington, IN) was inserted via the second puncture site and it was used to grasp the end of the guide wire in the suprarenal IVC (Fig. 1D). By simultaneous pulling of the wire loop, repositioning of the tip of the port catheter was successfully achieved and the tip was relocated at the initial position. The patient still had intermittent cough during the procedure and we observed lateral bending of the upper one third of the catheter to the right subclavian vein when the patient was coughing. After the reposition procedure, when we induced the patient to cough, we were able to again demonstrate this movement on fluoroscopy (Figs. 1E, F). This was very suggestive to have caused the catheter migration. Two days later, migration and coiling of the catheter were again demonstrated on the chest posteroanterior radiograph (Fig. 1G) in spite that there was no active physical movement by the patient. Because the tip of the catheter was still located in the superior vena cava and there was a considerable risk of remigration due to the patient's sustained cough, additional repositioning was not attempted thereafter. There was no additional positional change of the catheter seen on the serial follow up chest radiographs. Chemotherapy was delayed because the patient developed pneumonia. The port was used for administering central venous fluid and the function of the port catheter was preserved well. Sadly, about four weeks later, the patient expired due to aggravated pneumonia and respiratory failure.

Fig. 1.

Migration of implantable port catheter in 64-year-old man.

A. Implantable port catheter is inserted via jugular approach. Tip of catheter is well-placed in right atrium.

B. Four days after implantation procedure, chest PA radiograph shows coiled catheter and migration of tip from right atrium to right axillary vein. Associated pulmonary edema, cardiomegaly, air space consolidation with volume loss in left lung and pleural thickening with effusion in left hemithorax are also noted.

C. 5-Fr pigtail catheter is advanced to right subclavian vein to hook migrated port catheter.

D. Gooseneck snare wire and cobra catheter were used to capture wire.

E, F. After repositioning (E), catheter shows normal position and curve. However, when we induced patient to cough (F), bending of catheter toward subclavian vein (arrow) was found on fluoroscopy.

G. Two days later, recurrent catheter migration was found on chest radiograph. Coiling is noted in middle of catheter, but catheter tip is still located in superior vena cava.

DISCUSSION

An implantable port device provides an easily accessible central route for long-term chemotherapy patients. Many immediate and late complications of implantable port catheters have been reported on. The early complications include pneumothorax, hematoma, malposition, embolism or arrhythmia, and these are often related to the placement technique. The delayed complications include skin necrosis, infection, catheter fracture, occlusion or thrombosis (2).

Migration is one of the well-known complications of implantable port catheters. The incidence of spontaneous migration of a port catheter is reported to be about 0.9-1.8%, yet the mechanism of migration is not clear. The intravascular and extravascular portions of the catheter are not fixed and both sides are movable. The extravascular component of the port device can be moved by changing the body position or by physical movement, and especially in obese persons or woman with big breasts. Initial positioning of the port is important to prevent this kind of migration. The intravascular portion of the catheter is also movable and this is related with the inherent flexibility of the catheter. The intravascular component of the port catheter can be influenced by high intrathoracic pressure that's induced by coughing, sneezing, straining or weight lifting. A high infusion flow rate can also make the tip migrate. A case of tip migration after the catheter flushing has been reported (3).

Some authors have reported spontaneous migration of the catheter from the subclavian vein into the ipsilateral jugular vein (1, 3-5). Wu et al. (1) reported two cases of implantable port catheter tip migration in patients with severe cough. Our case also presented recurrent catheter migration and this was probably related to the patient's sustained cough. We identified the bending of the catheter that was induced by cough on fluoroscopy, and this strongly suggested that the migration of the catheter was the result of coughing. If the predisposing factors for this kind of the migration are not corrected, then remigration can occur.

Periodic check ups of the catheter location by performing chest radiograph are crucial to detect catheter tip migration. Some authors have recommended monitoring the catheter's position at least bimonthly when it is not in use and more frequently when it is in use (3). Once migration is detected, prompt correction is important because catheter tip migration can result in further complications such as thrombosis, venous phlebitis or occlusion. Revision or replacement is usually performed, but if the initial location of the catheter is ideal, then radiologic intervention by transfemoral snaring is useful to correct the tip position (6). The transfemoral approach has several advantages such as avoiding surgery and the associated risk of infection, and it decreases the patient's discomfort. This repositioning technique showed a high initial success rate of over 80% (7). The transfemoral snaring technique was a quick and easy method to reposition the catheter tip in our patient, and it was convenient for both the operator and the patient.

We present here a case of migration of the tip of a port catheter from the right atrium to the right axillary vein in a patient with severe cough. We are sure the coughing was the cause of the catheter tip migration, and we corrected the position of the catheter tip by transfemoral snaring. Radiologists should be familiar with catheter-related complications and their management, and they should pay attention to the catheter position not only during the procedure, but also on the follow up chest radiographs, and especially for the patients who suffer with severe cough.

References

- 1.Wu PY, Yeh YC, Huang CH, Lau HP, Yeh HM. Spontaneous migration of a Port-a-Cath catheter into ipsilateral jugular vein in two patients with severe cough. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:734–736. doi: 10.1007/s10016-005-4638-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballarini C, Intra M, Pisani Ceretti A, Cordovana A, Pagani M, Farina G, et al. Complications of subcutaneous infusion port in the general oncology population. Oncology. 1999;56:97–102. doi: 10.1159/000011947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasuli P, Hammond DI, Peterkin IR. Spontaneous intrajugular migration of long-term central venous access catheters. Radiology. 1992;182:822–824. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.3.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roblin D, Porter JC, Knight RK. Spontaneous migration of totally implanted venous catheter systems from subclavian into jugular veins. Thorax. 1994;49:281–282. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiGiacomo JC, Tarlian HS. Spontaneous migration of long-term indwelling venous catheters. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1991;15:574–577. doi: 10.1177/0148607191015005574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lois JF, Gomes AS, Pusey E. Nonsurgical repositioning of central venous catheters. Radiology. 1987;165:329–333. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.2.3310092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartnell GG, Gates J, Suojanen JN, Clouse ME. Transfemoral repositioning of malpositioned central venous catheters. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:329–331. doi: 10.1007/BF02570184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]