1. Introduction

Avian Tree of Life (TOL) projects using multilocus sequence data have begun to reweave Sibley and Ahlquist’s (1990) “tapestry” of the systematic relationships among birds, which was based on DNA-DNA hybridization. Many of these studies have focused on relationships among members of the most species-rich avian order, Passeriformes, or the perching birds (e.g., Barker et al., 2002, 2004; Cibois and Cracraft, 2004; Voelker and Spellman, 2004; Alström et al., 2006). Bringing direct sequence-based character evidence to bear on the systematic relationships among passerine birds has demonstrated that monophyly cannot be assumed for many lineages (Barker et al., 2004), from suborder to tribe, proposed by Sibley and Ahlquist (1990) and Sibley and Monroe (1990). However, many of the paraphyletic passerine lineages identified by modern sequence-based studies represent taxa identified as difficult to place or otherwise problematic by Sibley and Ahlquist (1990).

One of the consistently problematic groups has been the Bombycillidae (waxwings and allies). Sibley and Ahlquist (1990, p. 630) ultimately placed the Bombycillidae within the superfamily Muscicapoidea, but they were not confident of this placement. Recent studies have only confirmed the ambiguous placement of Bombycillidae, removing the family from the “core Muscicapoidea” because of poorly supported (low Bayesian credibility and bootstrap values) relationships with the core Muscicapoidea (Barker et al., 2002, 2004; Cibois and Cracraft, 2004; Voelker and Spellman, 2004), but keeping it in the superfamily.

A potentially confounding factor for placing the Bombycillidae within the passerine phylogeny is that membership in and relationships among members of the family have long been controversial; therefore, a more thorough sampling of the group is desirable. Many early taxonomies recognized the morphological similarities among waxwings (Bombycilla, 3 spp.), silky-flycatchers (Phainopepla, Phainoptila, and Ptilogonys, 4 spp.), and the palmchat (Dulus, 1 sp.) and proposed them as members of a single family Bombycillidae (Arvey, 1951; Beecher, 1953). However, studies of egg white proteins in the waxwings, silky-flycatchers, and palmchat indicated a close relationship between the former two, but not the latter (Sibley, 1970). The DNA-DNA hybridization analyses of Sibley and Ahlquist (1990) supported the close association among these three groups as indicated by morphology, leading these authors and Sibley and Monroe (1990) to maintain these species as members of the Bombycillidae, while also recognizing their differences by labeling them as distinct tribes (Bombycillini, Ptilogonatini, and Dulini; Table 1). Other modern taxonomies of the bombycillids (Voous, 1977; Cramp, 1988; AOU, 1998) have followed Wetmore (1930) in emphasizing skeletal differences among the three groups and elevating each to the family level (Bombyicillidae, Ptilogonatidae, and Dulidae). If the waxwings, silky-flycatchers, and palmchat are considered the “core” bombycillids (but relationships among the core groups are still unknown), then the remaining ambiguity lies in placement of the only other species ever to be considered among the bombycillids, the grey hypocolius (Hypocolius ampelinus). The grey hypocolius is generally considered to belong to a monotypic family, Hypocoliidae; however, at various points in its taxonomic history it has been considered closely allied with shrikes of the families Prionopidae and Laniidae (morphological characters; Mayr and Amadon, 1951), cuckoo-shrikes (jaw musculature; Campephagidae, Beecher, 1953), bulbuls (morphology; Pycnonotidae, Sibley and Ahlquist, 1990; Sibley and Monroe, 1990; Clements, 1991), and the Bombycillidae (plumage and morphological characters; Lowe, 1947; Delacour and Amadon, 1949). The most recent taxonomic treatment of waxwings, silky-flycatchers, palmchat, and grey hypocolius listed each as a separate but closely related family (Bombycillidae, Ptilogonatidae, Dulidae, and Hypocoliidae), reflecting the continued ambiguity of relationships among the groups (del Hoyo, 2005).

Table 1.

Specimen information.

| Superfamily | Family | Subfamily | Tribe | Representative taxon | Voucher Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corvoidea | Corvidae | Pachycephalinae | Hylocitrea bonensis | AMNH12574 | |

| Petroicidae | Tregellasia leucops | KUMNH 4701 (AM819), voucher BPBM | |||

| Muscicapoidea | Bombycillidae | Dulini | Dulus dominicus | AMNH 25478 (NKK1035) | |

| Ptilogonatini | Ptilogonys cinereus | FMNH (Tissue 6132) | |||

| Ptilogonatini | Ptilogonys caudatus (1) | FMNH 398067 | |||

| Ptilogonatini | Ptilogonys caudatus (2) | FMNH 393064 | |||

| Ptilogonatini | Phainopepla nitens | FMNH 343270 (MEX145) | |||

| Ptilogonatini | Phainoptila melanoxantha | AMNH (PEP2205) | |||

| Bombycillini | Bombycilla garrulus | AMNH Unvouchered (PRS1417) | |||

| Bombycillini | Bombycilla japonica | Mus. Nat. d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris | |||

| Bombycillini | Bombycilla cedrorum | AMNH (PAC631) | |||

| Hypocoliidae | Hypocolius ampelinus | AMNH | |||

| Cinclidae | Cinclus cinclus | AMNH NA (PRS2328) | |||

| Muscicapidae | Turdinae | Turdus falklandii | AMNH NA (PRS1825) | ||

| Sturnidae | Sturnini | Sturnus vulgaris | FMNH 389606 (MCP96-437) | ||

| Sylvioidea | Certhiidae | Certhiinae | Certhia familiaris | FMNH 351158 (S87-0026) | |

| Cisticolidae | Cisticola anonymus | AMNH 832156 (PB159) | |||

| Passeroidea | Fringillidae | Emberizinae | Thraupini | Thraupis cyanocephala | AMNH 24097 (GFB3133) |

In this study, we attempted to identify a monophyletic bombycillid lineage and to clarify the phylogenetic relationships among the members of this group. To identify membership within the bombycillid lineage, we first compared nuclear RAG-1 sequences from each putative bombycillid with the extensive RAG-1 dataset available for passerines (Barker et al., 2002; Barker et al., 2004). Then, to clarify relationships among bombycillid species, we analyzed sequence variation at three loci (RAG-1, RAG-2, and mtDNA).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Taxon Sampling, DNA isolation and sequencing

Because the purpose of this study was to identify taxa that belong to a monophyletic bombycillid lineage and to elucidate relationships within this lineage, we conducted phylogenetic analyses with all the putative members of the family, as described by Lowe (1947), Cramp (1988), Sibley & Monroe (1990), and Clements (1991). This list included: Bombycilla cedrorum, B. garrulus, B. japonica, Phainopepla nitens, Phainoptila melanoxantha, Ptilogonys cinereus, P. caudatus, Dulus dominicensis, and Hypocolius ampelinus (Table 1). Also included in the analysis was the Indonesian endemic and enigmatic olive-flanked whistler, Hylocitrea bonensis, which in an exploratory molecular analysis had demonstrated affinities with members of the Bombycillidae (Moyle, unpublished). In addition, we gathered new data from a number of non-bombycillid outgroups, representing all of the superfamily groups and most of the major lineages in Sibley and Monroe’s (1990) Passerida, to match RAG1 and RAG2 sequences already available from these taxa (Table 1). Genomic DNA was extracted from cryopreserved muscle tissue for all samples except Hypocolius ampelinus using a Qiagen DNeasy Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. Our sample of Hypocolius ampelinus came from a cut toepad from a museum specimen; therefore, genomic DNA was extracted from this sample using a modified Qiagen extraction protocol described by Nishiguchi et al. (2002). We amplified and sequenced 2 nuclear loci (partial single exons of the RAG-1 and RAG-2 genes, 2887 bp and 1164 bp, respectively) and two mitochondrial genes (ND2 and cyt b, 1041 bp and 1000 bp, respectively) for all samples except Hypocolius ampelinus, for which we were only able to sequence a portion of the RAG-1 gene and the nearly complete ND2 gene. Methods of amplification, sequencing, and sequence alignment followed Barker et al. (2002) for the nuclear loci and Klicka et al. (2005) for the mitochondrial genes. All newly-derived sequences have been deposited in GenBank (accession FJ177315-FJ177361).

2.2 Phylogenetic analyses

To identify all the members of a monophyletic bombycillid lineage, we conducted preliminary analyses with previously published RAG-1 sequences. RAG-1 sequences (2887 bp, for all taxa except Hypocolius ampelinus for which only a portion of the RAG-1 gene was amplifiable; see above) for all putative ingroup taxa plus sequences for several other enigmatic avian taxa were aligned by eye with RAG-1 data from Barker et al. (2004). This dataset included 153 taxa and 2947 bp of aligned sequence data. Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis (Multiphyl; Keane et al., 2007; SPR branch swapping on an initial neighbour-joining tree) using the GTR+I+Γ model of sequence evolution was performed using this alignment to determine the taxa that had affinity with the bombycillid lineage.

Bayesian and ML phylogenetic analyses were conducted on the expanded molecular dataset, which included RAG1, RAG2, and the mitochondrial genes. The fit of 56 nested nucleotide substitution models was evaluated separately for each gene region using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC1) option in the program multiphyl (Keane et al., 2007). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed using mrbayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck, 2003) and the best-fit nucleotide substitution models selected by MULTIPHYL for each of the separate gene regions (RAG-1, GTR+I+Γ; RAG-2, HKY+I+Γ; mtDNA, GTR+I+Γ). Two independent runs of four (one cold and three heated) Metropolis-coupled Markov chains were run for 20,000,000 generations, and trees were saved every 1000th generation. Both runs were checked by eye for stationarity, and the first 5000 saved trees from each run were discarded as burn-in. Consensus trees were constructed from the remaining 15,000 trees for each run to confirm that the independent runs converged upon the same topology and posterior estimates, and then were combined into a single consensus tree (made up of 30,000 trees total). All ML analyses were performed in multiphyl. multiphyl was used to evaluate nucleotide substitution model fit, construct a ML phylogeny, and test the robustness of the inferred phylogeny (100 nonparametric bootstrap replicates) for the complete concatenated dataset.

3. Results

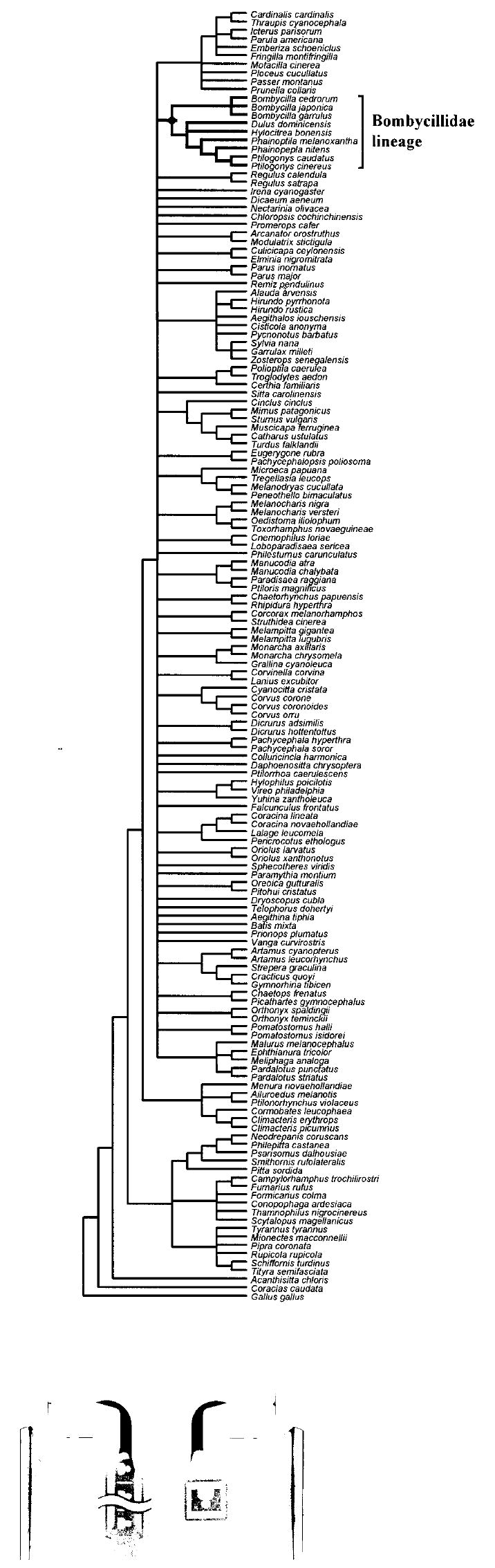

The preliminary analysis of the RAG-1 alignment suggested that all the putative Bombycillidae taxa listed above plus a single enigmatic SE Asian bird, Hylocitrea bonensis, belong to the bombycillid lineage (Fig. 1). Inclusion of these taxa in the bombycillid lineage was supported by 100% of 100 bootstrapped datasets and a synapomorphic insertion of a single codon in the RAG-1 reading frame (data not shown). Because only a partial RAG-1 sequence was available for Hypocolius, it was not included in the global tree search; however, the portion of the RAG-1 gene sequenced for Hypocolius contained the previously described and uniquely derived synapomorphic one-codon insertion possessed by all other taxa in the Bombycillid lineage, and Hypocolius was included in all subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny estimated from the expanded RAG-1 dataset (Barker et al. 2004) showing the position and membership of taxa within the Bombycillidae lineage. All branches with less than 70% bootstrap support were collapsed.

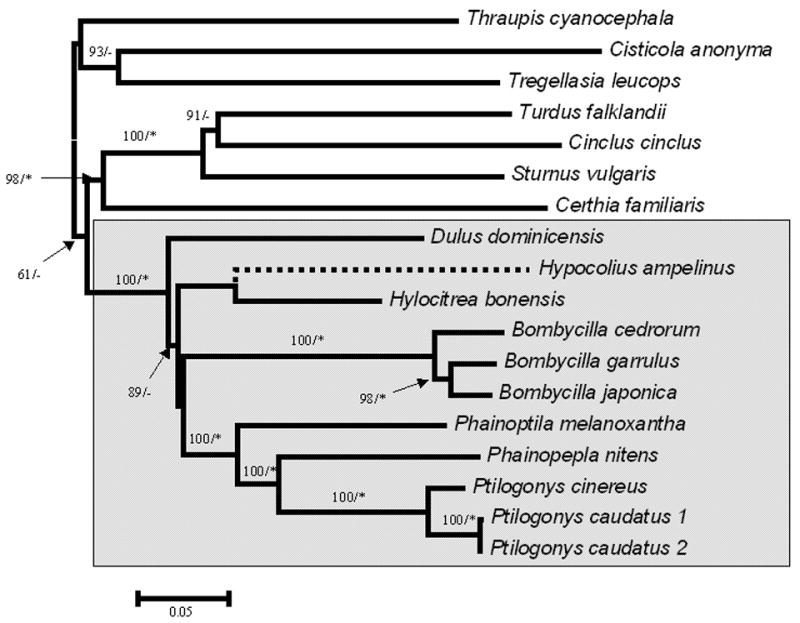

Sequence features and selected nucleotide substitution models for the 3-locus dataset (to clarify relationships among the bombycillids) are detailed in Table 2. Both Bayesian and ML phylogenetic analysis of this dataset yielded identical tree topologies (Fig. 2). The monophyly of the bombycillid clade was strongly supported (100% bootstrap and 1.00 posterior probability), and the members of this clade included Bombycilla cedrorum, B. garrulus, B. japonica, Phainopepla nitens, Phainoptila melanoxantha, Ptilogonys cinereus, P. caudatus, Dulus dominicensis, Hypocolius ampelinus, and Hylocitrea bonensis. Within the bombycillid clade there was strong support for the monophyly of the waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum, B. garrulus, B. japonica) and silky-flycatchers (Phainopepla nitens, Phainoptila melanoxantha, Ptilogonys cinereus, P. caudatus) and evidence that each of the other members belonging to monotypic genera (Dulus dominicensis, Hypocolius ampelinus, and Hylocitrea bonensis) was genetically very distinct (each on long branches; Fig. 2). Support for higher-level relationships among members of the clade were generally poorly supported; however, there was substantial bootstrap support (but not significant posterior probability) for an early divergence of Dulus from the rest of the members of the clade.

Table 2.

Sequence features for the 17 taxon, 3 locus (6093 bp) dataset.

| Locus |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| mtDNA (ND2 & cyt b) | RAG 1 | RAG 2 | |

| Number of Characters | 2042 | 2887 | 1164 |

| Phylogenetically informative (%) | 927 (45.4) | 235 (8.14) | 118 (10.14) |

| Nucleotide frequencies (%) | |||

| A | 28.43 | 31.28 | 29.23 |

| C | 32.53 | 20.49 | 21.64 |

| G | 12.07 | 23.91 | 22.88 |

| T | 23.7 | 23.75 | 25.92 |

| Average pairwise distance | 0.3846 | 0.0433 | 0.0486 |

| Model selected | GTR+I+Γ | GTR+I+Γ | HKY+I+Γ |

Figure 2.

Relationships among members of the Bombycillidae lineage. The phylogeny presented is the best maximum likelihood estimate rooted with Tregellasia, Thraupis, and Cisticola. The numbers above or beside the branches indicate maximum likelihood bootstrap support (100 replicates) and the asterisk (≥0.95) and dash (<0.95) indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities.

4. Discussion

The analysis of nuclear exon data (RAG-1) and combined nuclear exon (RAG-1 and RAG-2) and mtDNA data resolved the persistent ambiguity concerning the systematic affinities of the waxwings and their proposed allies. High bootstrap support and statistically significant posterior probability combined with a synapomorphic insertion in the reading frame of the RAG-1 gene identified membership in a monophyletic bombyillid clade. The members of this clade include all the previously hypothesized members of the bombycillids, Hypocolius ampelinus, and the enigmatic monotypic genus Hylocitrea bonensis. However, well-resolved phylogenetic relationships among members of the clade remain elusive.

To our knowledge, this is the first molecular phylogenetic treatment of the bombycillids to include sequence data from Hypocolius ampelinus, and this inclusion appears to resolve the longstanding controversy over this taxon’s association with the other members of the clade. Although we were unable to obtain complete sequences from the museum skin sample of Hypocolius, the data obtained were sufficient to confidently place it in the bombycillid clade. Specifically, the occurrence of a one-codon insertion in RAG1 also present in all other bombycillids strongly supports this contention. In addition, combined analysis of nuclear and mtDNA data with an array of outgroups representing most major lineages of Passerida yielded strong support for its placement (Fig. 2).

More surprising was the inclusion of Hylocitrea bonensis (olive-flanked whistler) in the bombycillid clade. Hylocitrea bonensis has an extremely convoluted taxonomic history and under various taxonomic treatments is currently placed within the Pachycephalidae (Morony et al., 1975), Corvidae (Sibley and Monroe, 1990), and Muscicapidae (Peters, 1987). A recent systematic assessment of the crown Corvida (Jønsson et al., 2008) included Hylocitrea bonensis and was the first to recognize that the species is not a member of the avian parvorder Corvida, but instead groups with parvorder Passerida. The placement of Hylocitrea within the bombycillid clade, a systematic relationship never previously hypothesized, further demonstrates the need to reconsider the systematics of many Wallacean taxa using molecular techniques.

The lack of statistically significant support for the basal nodes within the bombycillid lineage makes a biogeographic hypothesis for the evolution of the group difficult. If all poorly supported nodes are collapsed, then a large polytomy defines the relationships among the major lineages within the bombycillid clade. Two of the lineages stemming from the polytomy have multiple species and broad distributions: waxwings (Bombycilla; Holarctic) and silky-flycatchers (Ptilogonatinae; New World temperate and tropical regions). The remaining three lineages each include only a single species with restricted geographic distributions: Palmchat (Dulus; Hispaniola), grey Hypocolius (Iraq and Iran), and the olive-flanked whistler (Hylocitrea; SE Asia). The restricted geographic distributions and long branches of these monotypic taxa suggest that extinction has likely been important in the evolution of this group (Novacek and Wheeler, 1992). However, the inclusion of Hylocitrea in the bombycillid clade suggests that additional taxonomically enigmatic avian taxa might belong to this clade, and that future taxonomic studies of such taxa may help resolve systematic relationships within recognized groups.

While a thorough taxonomic revision of the bombycillid lineage is needed and should wait until a well-resolved phylogeny is available, we recommend the following taxonomic changes in the interim. The common ancestry of all the species within the clade should be recognized at the family level, Bombycillidae. The well-supported clades within the Bombycillidae (waxwings and silky-flycatchers) along with the monotypic lineages should all receive subfamily recognition: Bombycillinae (Bombycilla), Ptilogonatinae (Phainopepla, Phainoptila, Ptilogonys), Dulinae (Dulus), Hypocoliinae (Hypocolius), and Hylocitreinae (Hylocitrea). All generic and species nomenclature should remain the same.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the curators and staff of the ornithological frozen tissue collections at the American Museum of Natural History, Field Museum of Natural History, and the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History for their willingness to contribute resources to this study. The project described was also supported in part by Grant Number 2 P20 RR016479 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alström P, Ericson PGP, Olsson U, Sundberg P. Phylogeny and classification of the avian superfamily Sylvioidea. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;38:381–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Ornithologists’ Union. Check-list of North American Birds. 7. A.O.U.; Washington, D.C: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arvey MD. Phylogeny of the waxwings and allied birds. Publ Univ Kansas Mus Nat Hist. 1951;3:473–530. [Google Scholar]

- Barker FK, Barrowclough GF, Groth JG. A phylogenetic hypothesis for passerine birds: taxonomic and biogeographic implications of an analysis of nuclear DNA sequence data. Proc R Soc London, Ser B. 2002;269:295–308. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker FK, Cibois A, Schikler PA, Feinstein J, Cracraft J. Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11040–11045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401892101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecher WJ. A phylogeny of the oscines. Auk. 1953;70:270–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cracraft J, Barker FK. Passeriformes. In: Hedges SB, Kumar S, editors. The Timetree of Life. Oxford University Press; New York: In press. [Google Scholar]

- Cramp S. Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa: The Birds of the Western Palearctic Vol V: Tyrant Flycatchers to Thrushes. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford & New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cibois A, Cracraft J. Assessing the passerine “Tapestry”: phylogenetic relationships of the Muscicapoidea inferred from nuclear DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements J. Birds of the Word: a Checklist. 4. Ibis Publ.; Vista, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- del Hoyo J, Elliot A, Christie D, editors. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 10: Cuckoo-Shrikes to Thrushes. Lynx Edicions; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Delacour J, Amadon D. The Relationships of Hypocolius. Ibis. 1949;91:427–429. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jønsson KA, Irestedt M, Fuchs J, Ericson PGP, Christidis L, Bowie RCK, Norman JA, Pasquet E, Fjeldså J. Explosive avian radiations and multi-directional dispersal across Wallacea: Evidence from the Campephagidae and other Crown Corvida (Aves) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;47:221–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Naughton TJ, McInerney JO. MultiPhyl: A high-throughput phylogenomics webserver using distributed computing. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:W33–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm359. http://distributed.cs.nuim.ie/multiphyl.php. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klicka J, Voelker G, Spellman GM. A systematic revision of the true thrushes (Aves: Turdinae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;34:486–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr E, Amadon D. A classification of recent birds. Am Mus Novit. 1951;1496:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Morony JJ, Bock WJ, Farrand J. Amer Mus of Nat Hist. New York: 1975. Reference List of the Birds of the World. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiguchi MK, Doukakis P, Egan M, Kizirian D, Phillips A, Prendini L, Rosenbaum HC, Torres E, Wyner Y, DeSalle R, Giribet G. DNA isolation protocols. In: DeSalle R, Wheeler W, Giribet G, editors. Techniques in Molecular Systematics and Evolution. Birkhîuser, Basel; Germany: 2002. pp. 243–81. [Google Scholar]

- Novacek MJ, Wheeler QD. Extinction and Phylogeny. Columbia University Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JL. Check-list of Birds of the World. Harvard University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley CG. A comparative study of the egg-white proteins of passerine birds. Bull Peabody Mus Nat Hist. 1970;32:1–131. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley CG, Ahlquist JE. Phylogeny and Classification of Birds: a Study in Molecular Evolution. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley CG, Monroe BL., Jr . Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Voelker G, Spellman GM. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA evidence of polyphyly in the avian superfamily Muscicapoidea. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;30:386–394. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voous KH. List of Recent Holarctic Bird Species. British Ornithologists’ Union/Academic Press Ltd; London: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wetmore A. A systematic classification for the birds of the world. Proc U S Natl Mus. 1930;76:1–8. [Google Scholar]