Abstract

Here, we describe a case of a solitary pulmonary nodule due to Mycobacterium intracellulare infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case reported in Korea. A 45-year-old female, exhibiting no respiratory symptoms, was admitted to our hospital due to the appearance of a solitary pulmonary nodule on a chest radiograph. Computed tomography revealed a 2.5cm nodule with an irregular shape and some marginal spiculation in the right upper lobe. Positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose imaging revealed positive tumor uptake (maximum standardized uptake value=8.8). Bronchoscopy yielded no specific histological findings and no bacteriological findings. Percutaneous transthoracic lung biopsy revealed epithelioid granuloma but no acid-fast bacilli were detected. The patient received isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for the treatment of "tuberculoma". Five weeks after the patient was admitted, numerous mycobacterial colonies were detected on a bronchial washing fluid culture. These colonies were subsequently identified as Mycobacterium intracellulare. A final diagnosis of M. intracellulare pulmonary disease was made, and the patient's treatment regimen was changed to a combination therapy consisting of clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol.

Keywords: Pulmonary coin lesion, atypical mycobacteria, Mycobacterium avium complex, tuberculosis, tuberculoma

INTRODUCTION

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous organisms. They have been increasingly recognized as important causes of chronic pulmonary infection in immunocompetent individuals.1 Among NTM, the Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC), consisting of two species, M. avium and M. intracellulare, constitutes the most commonly encountered pathogen of NTM pulmonary disease in many countries including Korea.1-5 Similar to other granulomatous infections, NTM infection occasionally results in the formation of a solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN). These nodules are frequently an incidental finding in otherwise asymptomatic patients.6,7 There have been several previous reports of SPN due to MAC infection in the United States and Japan.8,9 Therefore, it is possible that some of the histologically diagnosed cases of "tuberculoma" in Korea are actually due to NTM infection, rather than to M. tuberculosis infection. However, until now, no such cases have been reported in Korea.

Here, we describe a case of a SPN due to M. intracellulare, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the first case reported in Korea.

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old woman was admitted to Samsung Medical Center after an incidental detection of an SPN on a chest radiograph. A chest radiograph obtained 4 years before revealed no such abnormality. The patient was a non-smoker. On admission, results of the patient's physical examination and laboratory tests were normal.

A chest radiograph, obtained at admission, revealed a nodular opacity in the right upper lobe (Fig. 1A). Chest computed tomography showed a 25×16mm nodule located in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe. This nodule featured necrotic low-attenuation portions and tiny calcifications were detected within the nodule (Fig. 1B). The lung window image revealed the irregular shape of the nodule, and also showed some marginal spiculation, making it difficulty to rule out malignancy (Fig. 1C). Positron emission tomography with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) imaging revealed positive tumor uptake in the nodule (maximum standardized uptake value=8.8).

Fig. 1.

45-year-old woman with Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease manifesting as an SPN. (A) The posteroanterior chest radiograph reveals a nodular opacity in the right upper lung zone (arrow). (B) Contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography scan (5-mm collimation) obtained at the level of the aortic arch reveals a solitary peripheral pulmonary nodule located in the right upper lobe. Note the necrotic low-ttenuation portions and tiny calcifications within the nodule. (C) Lung window image reveals the irregular shape of the nodule, which also exhibits some marginal spiculation.

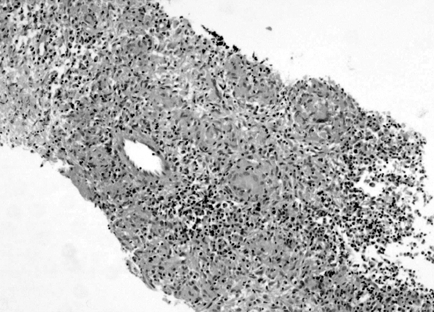

A bronchoscopy was performed. The results of a smear for acid-fast bacilli, a cytological examination, and a nucleic acid amplification test for M. tuberculosis in bronchoscopic washing fluid were all negative. Therefore, a fluoroscope-guided percutaneous transthoracic lung biopsy was conducted, and the biopsy specimens revealed epithelioid granuloma without caseating necrosis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Microscopic findings of the percutaneous transthoracic lung biopsy specimens indicate epithelioid granuloma (HE staining, ×100).

Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with "tuberculoma," and was prescribed a medication regimen including isoniazid (300mg), rifampin (600mg), ethambutol (1,200mg), and pyrazinamide (1500mg). Five weeks later, 200-500 mycobacterial colonies with confluent growth on Ogawa's egg medium (3+ growth) were detected on a bronchial washing fluid culture. The commercial nucleic acid amplification test for M. tuberculosis was negative (Gen-Probe Amplified Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Direct Test; Gen-Probe Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). The precise species identification was accomplished via a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism-based method that identified differences in the rpoB gene.10 The colonies were subsequently identified as M. intracellulare.

The patient was re-diagnosed with M. intracellulare pulmonary disease, and was put on a new treatment regimen, which consisted of daily clarithromycin (500mg bid), rifampin (600mg), and ethambutol (800mg). A chest radiograph taken 6 months after the new treatment regimen, showed a decreased nodular shadow in the right upper lobe. Total treatment duration was scheduled to last for 12 months, as initial and follow-up sputum cultures were all negative.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of an SPN due to MAC infection in Korea. SPNs are focal, round, or oval areas of increased opacity in the lung, which measure less than 3cm in diameter. These nodules are frequently discovered incidentally on chest radiographs or by computed tomography.11 SPNs can develop as a consequence of a variety of disorders including neoplasms, infection, inflammation, as well as vascular and congenital abnormalities.11 In the United States, more than 80% of SPN cases represent either lung cancers or benign granulomas, and these conditions occur with roughly equal frequency.12,13 The most common cause of benign granulomas is tuberculoma; this is particularly true in tuberculosis-endemic regions, such as Korea.14-16

Pulmonary tuberculoma is usually diagnosed via percutaneous needle aspiration or biopsy, and sometimes by surgical lung biopsy. Historically, SPNs that are pathologically similar to granulomas are often assumed to be attributable to M. tuberculosis infection, and, in such cases, bacteriological confirmation is not always sought.16,17 A similar pathology of granulomatous inflammation has been observed in fungal infections including histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and coccidioidosis. In Korea, the only reported cases have been patients who developed the disease after travel to regions in which this particular fungus is endemic.16

NTM infection may also result in the formation of SPNs, similar to those observed in association with other granulomatous infections.6,7 In most previous studies of tuberculomas, however, there was no distinction made between tuberculous and NTM infection.14-18 In 1981, Gribetz et al. reported that 12 of their 20 cases (60%), all of which had a solitary nodular shadow and positive acid-fast bacilli staining from a resected specimen, were due to MAC infection.8 Kobashi et al. recently reported 9 cases of SPNs due to MAC infection in Japan.9 These nodules ranged in size from 15 to 50mm.9 These findings suggest that some percentage of histologically-diagnosed solitary pulmonary "tuberculomas" is actually attributable to NTM infection, particularly MAC, rather than to M. tuberculosis infection. In these studies, most patients were treated with drug regimens for presumed tuberculosis, because the physician was frequently unaware of, or ignored, the fact that NTM and not M. tuberculosis had grown on the patients' cultures.8,9 This was also true in our case. We had initially diagnosed this patient with a pulmonary tuberculoma based on histological diagnosis and had initiated combined therapy with antituberculous drugs. However, the culture suggested a different diagnosis. In these situations, it is important that tissue be cultured from transthoracic lung biopsy or surgical lung biopsy specimens to differentiate M. tuberculosis from NTM.

In Korea, NTM pulmonary disease is most frequently caused by MAC, and less frequently by M. abscessus.2-5 We recently performed a 2-year study of 794 patients with positive NTM cultures at the Samsung Medical Center from 2002 to 2003.4 Among those, 195 (25%) patients were found to have clinical pulmonary disease, including MAC (n=94), and M. abscessus (n=64). Interestingly, there were no cases with an SPN due to NTM infection found during this study period.

Unlike M. tuberculosis, NTM are not obligate pathogens. Accordingly, the isolation of an NTM species from a respiratory sample is not sufficient evidence of NTM pulmonary disease. In 1997, the American Thoracic Society issued a revised set of diagnostic criteria for NTM pulmonary disease.1 According to these criteria, a patient with NTM pulmonary disease must have compatible symptoms and signs, and a compatible chest X-ray or computed tomography abnormalities, such as multiple nodules.1 The present case did not strictly satisfy the diagnostic criteria proposed by the American Thoracic Society, although there was evidence of histopathologic features of mycobacterial infection and the strong positive culture of NTM from bronchial washing specimens. The diagnostic criteria of NTM pulmonary disease must be expanded to include such cases with SPN.

In conclusion, MAC pulmonary disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an SPN, even when encountered in geographic regions with a high prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis, such as Korea. Our case report highlights the importance of differentiating between tuberculosis and MAC infection in cases of SPN, as well as the importance of differentiating between malignant and benign nodules.

References

- 1.Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(2 Pt 2):S1–S25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scientific Committee in Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. National survey of mycobacterial diseases other than tuberculosis in Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis. 1995;42:277–294. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Lee KS. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases in immunocompetent patients. Korean J Radiol. 2002;3:145–157. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2002.3.3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Jeon K, Kim TS, Lee KS, Park YK, et al. Clinical significance of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from respiratory specimens in Korea. Chest. 2006;129:341–348. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Lee KS. Diagnosis and treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: a Korean perspective. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:913–925. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.6.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller WT., Jr Spectrum of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Radiology. 1994;191:343–350. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.2.8153304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, Farrell MA, Patz EF., Jr Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: radiologic manifestations. Radiographics. 1999;19:1487–1505. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no101487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gribetz AR, Damsker B, Bottone EJ, Kirschner PA, Teirstein AS. Solitary pulmonary nodules due to nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Am J Med. 1981;70:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobashi Y, Yoshida K, Miyashita N, Niki Y, Matsushima T. Pulmonary Mycobacterium avium disease with a solitary pulmonary nodule requiring differentiation from recurrence of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Intern Med. 2004;43:855–860. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Park HJ, Cho SN, Bai GH, Kim SJ. Species identification of mycobacteria by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the rpoB gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2966–2971. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2966-2971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erasmus JJ, Connolly JE, McAdams HP, Roggli VL. Solitary pulmonary nodules: Part I. Morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Radiographics. 2000;20:43–58. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.1.g00ja0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lillington GA, Caskey CI. Evaluation and management of solitary and multiple pulmonary nodules. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Payne WS, Viggiano RW, Pairolero PC, Trastek VF. An integrated approach to evaluation of the solitary pulmonary nodule. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H, Kang SJ, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kwon OJ, Rhee CH, et al. Predictors for benign solitary pulmonary nodule in tuberculosis-endemic area. Korean J Intern Med. 2001;16:236–241. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2001.16.4.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi CA, Lee KS, Kim EA, Han J, Kim H, Kwon OJ, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: dynamic enhanced multi-detector row CT study and comparison with vascular endothelial growth factor and microvessel density. Radiology. 2004;233:191–199. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2331031535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HS, Oh JY, Lee JH, Yoo CG, Lee CT, Kim YW, et al. Response of pulmonary tuberculomas to anti-tuberculous treatment. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:452–455. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00087304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goo JM, Im JG, Do KH, Yeo JS, Seo JB, Kim HY, et al. Pulmonary tuberculoma evaluated by means of FDG PET: findings in 10 cases. Radiology. 2000;216:117–121. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl19117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida T, Yokoyama H, Kaneko S, Sugio K, Sugimachi K, Hara N. Pulmonary tuberculoma and indications for surgery: radiographic and clinicopathological analysis. Respir Med. 1992;86:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]