Abstract

Spontaneous regression of intra-abdominal cystic tumors in adults is unusual. Here, we present the case of an apparently spontaneous regression of a large intra-abdominal cystic mass found in the postpartum period of an 18-year-old woman. The regression was demonstrated using serial computed tomography (CT) examinations over a two-year period.

Keywords: Lymphangioma, CT, MRI

Intra-abdominal cystic tumors are occasionally encountered in clinical practice, and management depends on the clinical symptoms, size of the cyst, and the degree of clinical suspicion for malignancy.1 Although histological diagnosis may be difficult, imaging can provide useful information for the planning of treatment.2-4 If a cystic mass is asymptomatic and determined to be benign, close surveillance may be preferable to intervention. Cystic lymphangioma is one of the more common intra-abdominal cystic tumors and may present with characteristic imaging features; this can potentially provide the radiologist with a specific preoperative diagnosis.2,5,6 The growth of a lymphangioma can be seen during pregnancy.7-9 Spontaneous regression of nuchal or mediastinal lymphangioma has been reported, but regression of an intra-abdominal lymphangioma has not.10-13 Here, we report the peculiar case involving a postpartum woman and the gradual regression of a radiologically suggested intra-abdominal cystic lymphangioma.

CASE REPORT

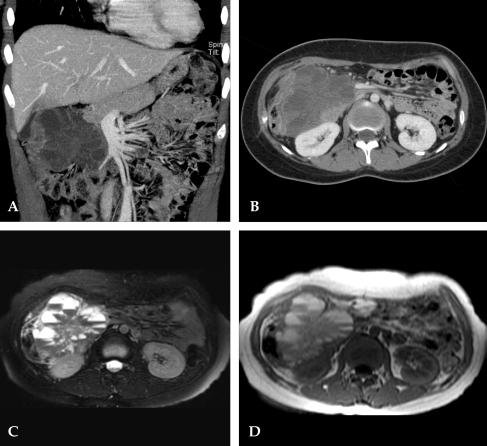

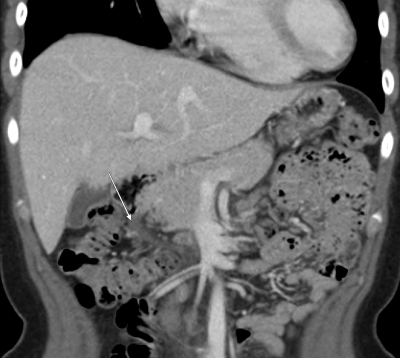

An 18-year-old woman was referred to our institution for further evaluation of a painful and palpable mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. She reported feeling the mass immediately after a cesarean section which she had had two months prior. She had no history of recent trauma or coexisting disease. Laboratory data, including tumor markers (CA 19-9 and CA 125), were within normal limits. Initial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an 11-cm multilobulated, multilocular, heterogeneous cystic mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The mass displaced the hepatic flexure of the colon inferiorly, with compression of the pancreatic head and duodenum, and displaced the gallbladder superiorly (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of intestinal wall or adjacent organ invasion. The average attenuation within the cysts was 28 Hounsfield units (range, 15-40) and the internal fluid-fluid level within the cysts was visible on CT. On axial T2-weighted spin echo image (8000/ 105) with fat suppression (1C) and axial T1-weighted incoherent gradient-echo (SPGR) images (230/4.2) (1D), the upper portions of the fluid within the cysts showed high signal intensity, and the area of the lower portions of fluid showed low signal intensity. These findings may reflect the presence of variable stages of hemorrhage within the cysts. A tentative diagnosis of a retroperitoneal cystic lymphangioma with internal hemorrhage was made based on the imaging findings. A follow-up CT scan two months later revealed that the mass had decreased from 11cm to 7cm. There was also a reduction in the degree of intra-cystic hemorrhage, and the patient no longer complained of discomfort. Serial follow-up study by CT and MRI showed progressive reduction in the size of the mass, and on the sixth follow-up CT scan two years later, the cystic mass was no longer visible except for a tiny residual lesion in the abdomen (Fig. 2). No treatment was administered, and the patient remains in good health.

Fig. 1.

Coronal (A) and axial (B) view of contrast enhanced CT scan demonstrating a large, multilobulated, multilocular, heterogeneous cystic mass with internal septa in the right upper quadrant abdomen. On axial T2-weighted spin echo image (8000/105) with fat suppression (C) and axial T1-weighted incoherent gradient-echo (SPGR) images (230/4.2) (D), the signal intensity of the upper portions of the fluid within the cysts showed high signal intensity, and the area of the lower portions of fluid showed low signal intensity.

Fig. 2.

Follow-up CT scan two years after initial examination shows marked regression of the mass with a tiny remaining cystic lesion in the right upper quadrant abdomen.

DISCUSSION

Intra-abdominal cystic tumors usually require surgical resection for a definitive diagnosis. In the present case, characteristic imaging features suggested internal hemorrhage in a cystic lymphangioma. Therefore, the patient was watched closely and no surgical exploration was performed.

The differential diagnosis of intra-abdominal cystic masses includes cystic lesions of lymphatic, mesothelial, enteric or urogenital origin, dermoid cysts or teratomas, and pseudocysts from trauma or infectious origins.3,4,14 Cystic degeneration of solid tumors may also be a possible cause.4

Imaging features are valuable in the diagnosis of these lesions. Characteristic radiologic findings (and their respective lesions) are as follows:3,4,15 Cystic lymphangioma usually presents as a large, multilocular cystic mass with internal chylous component, but hemorrhagic contents may also, though rarely, be present;16 enteric duplication cysts have enhancing thick walls. Enteric cysts have a few thin septa but no discernible wall; nonpancreatic pseudocysts usually present as a unilocular or multilocular cystic masses, with thick enhancing walls and internal hemorrhagic or purulent contents; cystic mesothelioma has no discernible wall or internal septa; cystic mesothelioma and cystic spindle cell tumors tend to invade or recur locally.17,18 Cystic teratomas have calcification and fat components. Other neoplastic cystic masses usually contain a solid component, and have not shown spontaneous regression.

In the present case, a radiological impression of a cystic lymphangioma was rendered based on such findings as hemorrhagic fluid levels with a honeycombing appearance of the cystic lesion with numerous septa in a thin-walled cystic mass. Although a diagnosis of cystic lymphangioma can be made by a histologic examination, the preoperative diagnosis on imaging can be complicated by superimposed reactive changes.19 In our case, the absence of an enhancing solid component or mural nodules, and the absence of recent trauma or infection excluded the possibility of complicated pseudocysts or other tumors.

Cystic lymphangioma is thought to be due to malformed or malpositioned congenital lymphatic tissue, but other factors such as abdominal trauma, lymphatic obstruction, inflammatory processes, surgery, or radiation therapy may lead to the secondary formation of such tumors.20 Mesenteric cysts are uncommon in pregnancy but can occur at any stage during gestation.7 There have been reports that mesenteric lymphangioma may be associated with the enlargement of the uterus during pregnancy.8 In previous cases, patients were treated surgically. However, in our case, the large mass found in the postpartum period demonstrated progressive, spontaneous regression without treatment. There is no known theory regarding the spontaneous regression of intra-abdominal cystic lymphangioma. We believe that the source of the initial pain was the internal hemorrhage of the cyst. Progressive resolution of internal hemorrhage may have contributed to the gradual spontaneous regression of the cyst, along with resolution of the pain.

Lymphangiomas are usually asymptomatic but may present as acute abdominal pain requiring surgery.20 The intra-abdominal location accounts for less than 2% of lymphangiomas, and the most common location within the abdominal cavity appears to be the mesentery of the small or large intestine.20 In the fetal stage or during childhood, spontaneous resolution has been reported for cystic hygromas originating in the neck or mediastinum;10-13 however, spontaneous resolution has not been reported for intra-abdominal lymphangioma. This may be due to the fact that histologic diagnosis has been based on surgical resection. Spontaneous regressions of mesothelioma have been reported,21,22 but such lesions had a solid appearance and can be distinguished from our case by imaging features.

CT scan images are valuable in the diagnosis of these lesions. The most characteristic radiologic finding of intra-abdominal cystic lymphangioma is a mono- or multiloculated cystic lesion with enhanced walls, in addition to multiple thin septa containing uncomplicated fluid commonly located on the left side of the abdomen.5 MRI is useful for characterization of the cystic consistency; the most characteristic feature was heterogeneity with low signal intensity (similar to that of muscle) on T1-weighted images, and high signal intensity (greater than that of fat) on T2- weighted images.16 In the present case, the layering of fluid with different signal intensity within the cyst suggested the presence of internal hemorrhage; the pain may have resulted from the hemorrhage or inflammation of the cyst.23

The lack of a histologic diagnosis is a limitation of this report. However, advanced imaging techniques may render a correct diagnosis for lesions presenting with specific characteristics.4,6 Although the diagnosis was not histologically confirmed, our case suggests that a period of careful observation before a surgical treatment may be justified if the lesion demonstrates characteristic features of a benign cystic lesion on imaging studies.

In conclusion, we saw an unusual case of a large cystic lymphangioma with internal hemorrhage diagnosed during the postpartum period. The lesion regressed spontaneously without treatment. Imaging studies were valuable for evaluating gross features and in assessing serial changes in the lesion. Therefore, if the imaging findings are characteristic of a benign cystic lymphangioma, conservative management with close surveillance may be a treatment option in patients without signs and symptoms necessitating a surgery.

References

- 1.Chen JS, Lee WJ, Chang YJ, Wu MZ, Chiu KM. Laparoscopic resection of a primary retroperitoneal mucinous cystadenoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:343–345. doi: 10.1007/s005950050137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ros PR, Olmsted WW, Moser RP, Dachman AH, Hjermstad BH, Sobin LH. Mesenteric and omental cysts: histologic classification with imaging correlation. Radiology. 1987;164:327–332. doi: 10.1148/radiology.164.2.3299483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoupis C, Ros PR, Abbitt PL, Burton SS, Gauger J. Bubbles in the belly: imaging of cystic mesenteric or omental masses. Radiographics. 1994;14:729–737. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.14.4.7938764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang DM, Jung DH, Kim H, Kang JH, Kim SH, Kim JH, et al. Retroperitoneal cystic masses: CT, clinical, and pathologic findings and literature review. Radiographics. 2004;24:1353–1365. doi: 10.1148/rg.245045017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson AJ, Hartman DS. Lymphangioma of the retroperitoneum: CT and sonographic characteristic. Radiology. 1990;175:507–510. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.2.2183287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi JY, Kim MJ, Chung JJ, Park SI, Lee JT, Yoo HS, et al. Gallbladder lymphangioma: MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:54–57. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liew SC, Glenn DC, Storey DW. Mesenteric cyst. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64:741–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb04530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torashima Y, Yamaguchi J, Taniguchi K, Fujioka H, Shimokawa I, Izawa K, et al. Surgery for ileal mesenteric lymphangioma during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:616–620. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quack Loetscher KC, Jandali AR, Garzoli E, Pok J, Beinder E. Axillary cavernous lymphangioma in pregnancy and puerperium. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2005;60:108–111. doi: 10.1159/000085584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warner AA, Kofinas AD, Melone PJ. Spontaneous resolution of cystic hygroma. Prenat Diagn. 1990;10:758. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970101111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Distell BM, Hertzberg BS, Bowie JD. Spontaneous resolution of a cystic neck mass in a fetus with normal karyotype. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:380–382. doi: 10.2214/ajr.153.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson WJ, Katz VL, Thorp JM. Spontaneous resolution of fetal nuchal cystic hygroma. J Perinatol. 1991;11:213–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu MP, Wu RC, Lee JS, Yao WJ, Kuo PL. Spontaneous resolution of fetal mediastinal cystic hygroma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995;48:295–298. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(94)02286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Perrot M, Bründler M, Tötsch M, Mentha G, Morel P. Mesenteric cysts. Toward less confusion? Dig Surg. 2000;17:323–328. doi: 10.1159/000018872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takiff H, Calabria R, Yin L, Stabile BE. Mesenteric cysts and intra-abdominal cystic lymphangiomas. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1266–1269. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390350048010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel MJ, Glazer HS, St Amour TE, Rosenthal DD. Lymphangiomas in children: MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;170:467–470. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.2.2911671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozgen A, Akata D, Akhan O, Tez M, Gedikoglu G, Ozmen MN. Giant benign cystic peritoneal mesothelioma: US, CT, and MRI findings. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:502–504. doi: 10.1007/s002619900387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bos SD, Jansen W, Ypma AF. Multicystic mesothelioma presenting as a pelvic tumour: case report and literature review. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995;29:225–228. doi: 10.3109/00365599509180568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Intraabdominal cystic lymphangiomas obscured by marked superimposed reactive changes: clinicopathological analysis of a series. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daniel S, Lazarevic B, Attia A. Lymphangioma of the mesentery of the jejunum: report of a case and a brief review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:726–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maniwa Y, Tsubota N, Yoshimura M, Murotani A, Miyamoto Y, Takagi Y, et al. A case of the localized fibrous mesothelioma which size decreased temporarily. Kyobu Geka. 1994;47:948–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson BW, Robinson C, Lake RA. Localised spontaneous regression in mesothelioma-possible immunological mechanism. Lung Cancer. 2001;32:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iyer R, Eftekhari F, Varma D, Jaffe N. Cystic retroperitoneal lymphangioma: CT, ultrasound and MR findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1993;23:305–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02010922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]