Abstract

Ependymomas usually develop from neuroectodermal organs. Here, we present an ependymoma arising from the pelvic cavity. A 27-year-old Korean female was admitted to the hospital with a sensation of abdominal fullness. Imaging studies revealed a huge heterogeneous nodular mass in the pelvis and lower abdomen. Laparotomy showed that two large masses with multiple nodules were located between the uterus and rectum and uterus and bladder, respectively. Histologically, the tumor was characterized by compact columnar neoplastic cells divided by fibrovascular septae. The neoplastic cells formed true ependymal rosettes and perivascular pseudorosettes. Immunohistochemical staining showed a strong positive reaction for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin and a partial positive reaction for S100 and EMA. The tumor was thus diagnosed as an ependymoma arising from the pelvic cavity. The patient was treated with a debulking operation and chemotherapy based upon the in vitro chemosensitivity test results. The patient was free of cancer for 4 years following surgery. This is a rare case of extraneural ependymoma for which an in vitro chemosensitivity test was critical in determining the multidisciplinary approach for treatment.

Keywords: Ependymoma, in vitro chemosensitivity test, chemotherapy

INTRODUCTION

In children, ependymoma is a frequently encountered brain tumor but in adults it is a rare tumor arising from extraneural sites with fewer than ten cases reported in the literature. We report a case of a 27-year-old woman with an ependymoma arising from the pelvic cavity, which was treated by surgery and a combinational chemotherapy of topotecan and carboplatin. To our knowledge, this is the first extraneural ependymoma case in which an in vitro chemosensitivity test was used to determine the most effective chemotherapy drugs for treatment.

CASE REPORT

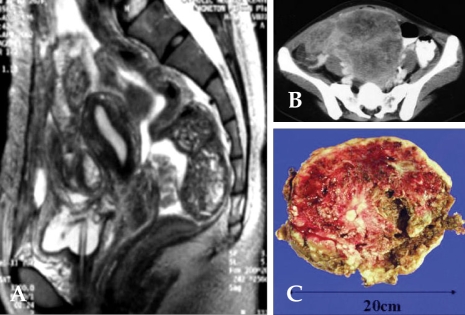

In 2002, a 27-year-old Korean female was admitted to the hospital due to a sensation of abdominal fullness. CT scan and MRI revealed a huge heterogeneous nodular mass in the pelvis and lower abdomen (Fig. 1). Under the diagnosis of ovarian cancer, a laparotomy was performed. During the operation, two large masses (20 × 20 cm and 8 × 8cm) with clear-cut margins were located between the uterus and rectum and the uterus and bladder, respectively. In addition, multiple small-sized nodules were disseminated at the double pouch, rectal wall, peritoneal wall, and right subphrenic area. We performed a wide excision of the two large masses but not the widespread small-sized nodules.

Fig. 1.

Two 20 × 20cm and 8 × 8cm-sized large masses with clear cut margins were located between the uterus and rectum and the uterus and bladder, respectively (A and B). Carcinomatosis and seeding metastasis on Rt. subhepatic space were also observed (A and B). On gross pathology, the cut surface of one of the masses shows a pale brown fish flesh solid and partly white pale brown friable appearance with several hemorrhagic foci (C).

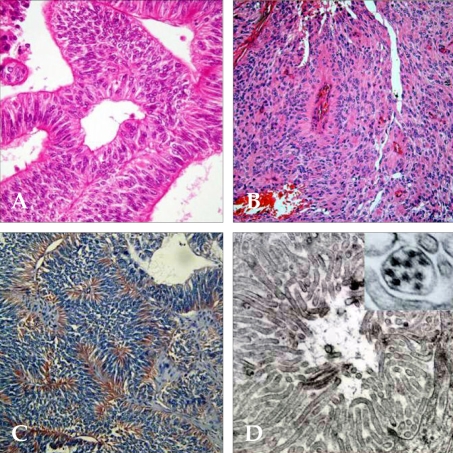

The histopathological examination of the masses showed a mostly solid growth of compact columnar neoplastic cells divided by fibrovascular septae. The neoplastic cells formed true ependymal rosettes and perivascular pseudorosettes, in which long cytoplasmic process headed for the vessel wall (Fig. 2A and 2B). The tumor did not show any necrosis or psammoma body. The neoplastic cells showed mild to moderate cellular pleomor-phism and infrequent mitotic counts. Immunohistochemical staining revealed a strong positive reaction for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin and a partial positive reaction for S100 and EMA (Fig. 2C). Immunostaining for hormone receptor showed diffuse and focal staining for progesterone and estrogen receptor. In most of the tumorogenic area, the proliferative index by MIB-1 was around 10%. A primary diagnosis of ependymoma arising from the pelvic cavity was made. We excluded involvement of the spine and brain by whole body bone and whole body PET (Positron emission tomography) scans. To determine the appropriate chemotherapy treatment, we performed an in vitro chemosensitivity test using the 3-(4, 5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H tetrazolium bromide (MMT) assay. This assay showed an inhibition rate of 67% for cisplatin, 67% for carboplatin, 54% for topotecan, 32% for doxorubicin, 24% for gemcitabine, 18% for ifosfamide, 6% for VP-16, 4% for paclitaxel and 2% for docetaxel. The patient was treated with eight cycles of combinational chemotherapy with intravenous topotecan (1mg/m2 for 5 days) and carboplatin (AUC 5, day 1), resulting in a partial response shown by follow-up imaging studies. A second open-look laparotomy was performed and revealed an irregular mass under the right diaphragm and the multiple nodular lesions in the lower abdominal and pelvic cavity. Right hemidiaphragmectomy and peritoneal resection were performed. Few viable tumor cells were identified by light microscopic examination. The patient received an additional 4 cycles of chemotherapy with doxorubicin and gemcitabine based upon the previous chemosensitivity test results. The patient is still alive and has not had a tumor recurrence.

Fig. 2.

Tumor cells are arranged in true perivascular pseudorosettes (A) and ependymal rosettes (B). Tumor cells show positive immunoreactivity for GFAP (C). Ultrastructural examination revealed compact arrangement of the tumor cells interlacing with the cytoplasmic process and abundant intermediate filaments in the cytoplasmic process. The presence of cilia in the cyst and intracytoplasmic lumen and intercellular junctions; Original magnification (D): × 12,000, right upper: × 30,000.

DISCUSSION

Ependymomas usually develop from neuroectodermal organs. Primary extraneural ependymomas are rare and are typically defined as a sacrococcygeal, pelvic or extrapelvic ependymoma depending on the site of origin. The most common site for extraneural ependymomas is the sacrococcygeal region, with more than 50 cases reported. The most common pelvic ependymomas originate in the ovary (9 cases) and sites of origin for extraovarian pelvic ependymomas (6 cases) include the mesovarium,1 broad ligament,2 uterosacral ligament,3 small bowel4 and omentum.5 Other sites of origin include lung6 and liver.7 We are reporting an ependymoma arising from the pelvic cavity between the uterus and rectum, which is an extremely rare location. Extramedullary ependymomas arising in the sacrococcygeal region are thought to arise from ependymal cell rests, which might result from incomplete regression of the caudal cell nests. The origin of this ependymoma is supported by the observation that most of the pelvic ependymomas are myxopapillary types, which is a characteristic of an ependymoma arising from the filum terminale. However, extramedullary ependymoma that do not originate from filum terminale such as ependymoma in the pelvic cavity and ovarian ependymomas, are not considered myxopapillary type. Therefore, the widely accepted hypothesis regarding the origin of these ependymomas is as follows:2,3,8

1. a germ cell origin regarded to teratoma

2. "neometaplasia" of the peritoneum or mullerian duct-derived tissues

3. congenitally ectopic tissue or fetal tissue deposited at the pelvic cavity

In our case, the ependymoma from the pelvic cavity expressed estrogen and progesterone receptors but did not show a myxopapillary pattern suggesting that a primitive germ cell that fails to integrate into the ovary could become malignant during the reproductive period.

Because this neoplasm is extremely rare, only a few cases have been reported and all these involved surgical treatment. Chemotherapy has been given to ovarian ependymoma patients (6/9) and to extraovarian pelvic ependymoma patients (2/7). Three patients with ovarian ependymoma received irradiation with chemotherapy and 2 patients with extraovarian pelvic ependymoma received chemotherapy without radiotherapy. In these cases, radiotherapy was not performed because the tumor widely disseminated and the initial response to chemotherapy showed tumor regression, which led to subsequent surgery. The period of clinical follow-up ranged from 7 months to 51 years and the recurrence rate was about 41% (7/17). The chemotherapy regimens were variable. Cisplatin is the most commonly used drug, accounting for up to 20% of all cases. Cyclophosphamide, etoposide, bleomycin, vinblastin and adriamycin have also been used against this dismal malignancy.

Even though ependymoma is a slowly growing tumor, the prognosis is generally poor due to the large tumor size, carcinomatosis and the high proliferative index of 10% by MIB-1 (p53 and MIB-1 in central ependymoma suggest high grade). However, our patient has survived more than 4 years and currently shows no evidence of recurrence.

In vitro chemosensitivity does not guarantee a similar in vivo response because sampled tissue is not necessarily a true representation of the whole tumor. Although the in vitro chemosensitivity test has been evaluated for more than 20 years, it is not recommended for use outside of a clinical trial setting because the potential clinical benefits including survival are not yet established. However, some clinical trials showed a better response rate with an in vitro-selected chemotherapy regimen than with empirically-derived treatments.9,10 In conclusion, we found that a combination of appropriate surgery and in vitro chemosensitivity-based chemotherapy was an effective and successful treatment for this rare pelvic ependymoma and this approach may be a worthwhile option for the treatment of future cases of this rare malignancy.

References

- 1.Grody WW, Nieberg RK, Bhuta S. Ependymoma-like tumor of the mesovarium. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109:291–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell DA, Woodruff JM, Scully RE. Ependymoma of the broad ligament. A report of the two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:203–209. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duggan MA, Hugh J, Nation JG, Robertson DI, Stuart GC. Ependymoma of the uterosacral ligament. Cancer. 1989;64:2565–2571. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891215)64:12<2565::aid-cncr2820641226>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofman V, Isnard V, Chevallier A, Motamedi JP, Michiels JF, Hassoun J, et al. Pelvic ependymoma arising from the small bowel. Pathology. 2001;33:26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dekmezian RH, Sneige N, Ordonez NG. Ovarian and omental ependymomas in peritoneal washings: cytologic and immunocytochemical features. Diagn Cytopathol. 1986;2:62–68. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840020113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crotty TB, Hooker RP, Swensen SJ, Scheithauer BW, Myers JL. Primary malignant ependymoma of the lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:373–378. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiendl H, Feiden W, Scherieble H, Renz T, Dichgans J, Weller M. March 2003: a 41-year-old female with a solitary lesion in the liver. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:421–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinman GM, Young RH, Scully RE. Ependymoma of the ovary: report of three cases. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:632–638. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Hoff DD, Kronmal R, Salmon SE, Turner J, Green JB, Bonorris JS, et al. A Southwest Oncology Group study on the use of a human tumor cloning assay for predicting response in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1991;67:20–27. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910101)67:1<20::aid-cncr2820670105>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samson DJ, Seidenfeld J, Ziegler K, Aronson N. Chemotherapy sensitivity and resistance assays: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3618–3630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]