Abstract

Mycobacterium xenopi is a nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) that rarely causes pulmonary disease in Asia. Here we describe the first case of M. xenopi pulmonary disease in Korea. A 66-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a 2-month history of productive cough and hemoptysis. His past medical history included pulmonary tuberculosis 44 years earlier, leading to a right upper lobectomy. Chest X-ray upon admission revealed cavitary consolidation involving the entire right lung. Numerous acid-fast bacilli were seen in his initial sputum, and M. xenopi was subsequently identified in more than five sputum cultures, using molecular methods. Despite treatment with clarithromycin, rifampicin, ethambutol, and streptomycin, the infiltrative shadow revealed on chest X-ray increased in size. The patient's condition worsened, and a right completion pneumonectomy was performed. The patient consequently died of respiratory failure on postoperative day 47, secondary to the development of a late bronchopleural fistula. This case serves as a reminder to clinicians that the incidence of NTM infection is increasing in Korea and that unusual NTM are capable of causing disease in non-immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: Atypical mycobacteria, Mycobacterium xenopi, Korea

INTRODUCTION

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous organisms, increasingly recognized as an important cause of chronic pulmonary infection in non-immunocompromised individuals.1 Among NTM, the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and M. abscessus constitute the most commonly encountered agents of NTM lung disease in Korea.2-4

Mycobacterium xenopi is a slow-growing NTM. The prevalence of M. xenopi varies geographically; it is one of the most commonly isolated NTMs in the United Kingdom,5 France,6 and Canada.7 In contrast, it is less commonly identified in the U.S.1 M. xenopi is a very rare pathogen of pulmonary disease in Asia. Until recently, only eight cases of M. xenopi pulmonary disease have been reported in Japan.8

Here, we describe a case of M. xenopi pulmonary disease, the first reported in Korea. The isolates were identified, using both conventional microbiological methods and heat-shock protein 65 gene (hsp65) sequence analysis.

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old man with no history of smoking was referred to our hospital for further examination and management of probable NTM lung disease. His history was significant for pulmonary tuberculosis 44 years earlier, for which he underwent right upper lobectomy to palliate recurrent hemoptysis.

Two months before admission to our hospital, the patient reported a 2-month history of productive cough, hemoptysis, and mild fever. He also experienced 10kg weight loss, associated with a poor appetite. Chest X-ray demonstrated cavitary consolidation in the right lung, and an acid-fast bacilli (AFB) stain was positive in his sputum (2+). The patient was initially diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and received isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. After two months of anti-tuberculous treatment, during which the patient failed to improve clinically, he was transferred to our hospital.

Physical examination upon presentation showed that the patient was 172cm tall and weighed 54kg. Vitals included a body temperature of 37.5℃ and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. Coarse crackles over the right hemithorax were revealed upon auscultation. No lymphadenopathy was appreciated.

Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 10,520/µL, with a differential of 84.7% neutrophils. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 120mm/h, and the level of C-reactive protein was elevated at 16.55mg/dL. Total proteins were 7.0g/dL, with a low albumin level (2.3g/dL). A human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative.

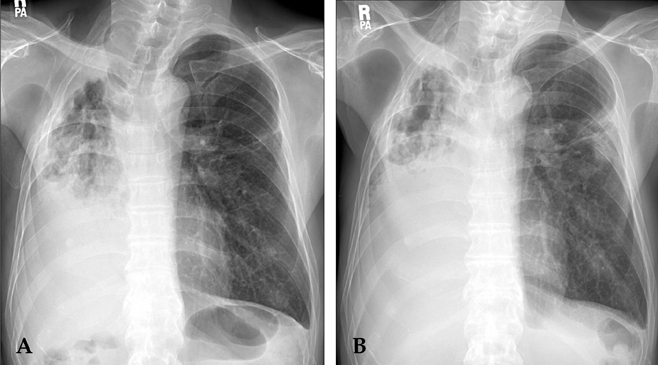

Chest radiograph revealed a huge cavitary consolidation involving the entire right lung (Fig. 1A). Significant AFBs were visualized in multiple sputum specimens; however, repeated nucleic acid amplification tests for M. tuberculosis, using a commercial DNA probe (Gen-Probe Amplified Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Direct Test; Gen-Probe Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) were negative. Combination chemotherapy, which included clarithromycin (1000mg/day), rifampicin (600mg/day), ethambutol (800mg/day), and streptomycin (750mg intramuscular injection three times per week), was initiated under the tentative diagnosis of MAC disease.

Fig. 1.

A 66-year-old man with Mycobacterium xenopi pulmonary disease. (A) The posteroanterior chest radiograph revealed cavitary consolidation in the entire right lung. (B) The follow-up chest radiograph, after antibiotic treatment for four months, showed that the size of the cavitary consolidation in the right lung had increased and that a new infiltrative shadow appeared in the left lung.

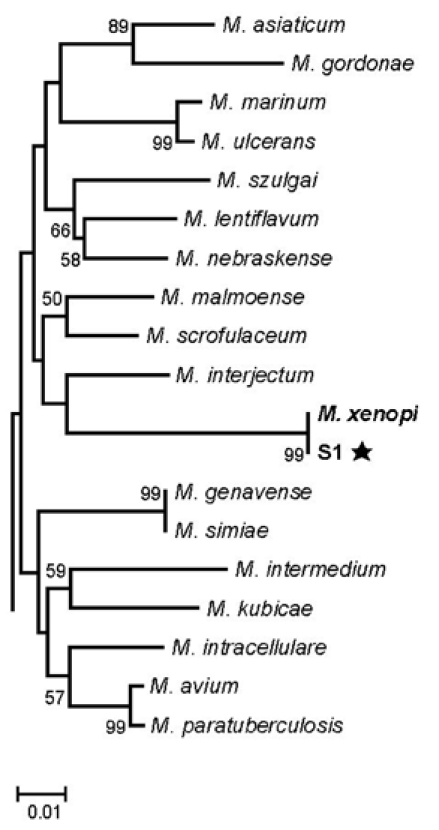

Subsequently, more than five isolates of mycobacteria, obtained from sputum specimens at both hospitals, were transferred to the Korean Institute of Tuberculosis and Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the College of Medicine of Seoul National University. Species isolation was performed, using both conventional microbiological and molecular methods.9,10 All isolates were identified as M. xenopi, based on heat-shock protein 65 gene (hsp65) sequence analysis, showing 100% sequence similarity with the M. xenopi reference strains (Fig. 2). Other mycobacteria were not isolated along with M. xenopi. The isolates from this patient were sensitive to isoniazid (0.2 µg/mL), rifampicin (40 µg/mL), streptomycin (4 µg/mL), and kanamycin (40 µg/mL); but were resistant to ethambutol (2.0 µg/mL) on Lowenstein-Jensen media. The isolates were also susceptible to clarithromycin (16 µg/mL), rifabutin (2 µg/mL), amikacin (16 µg/mL), and moxifloxacin (1 µg/mL) in Middlebrook7H9 broth.

Fig. 2.

Species identification of strain S1 in this study based on a comparative analysis of partial hsp65 sequences (422bp). The tree was constructed from all 56 mycobacteria reference strains and strain S1, using the neighbor-joining method. The percentages indicated at nodes represent bootstrap levels supported by 1,000 re-sampled datasets. Bootstrap values < 50% are not shown.

Despite four months of antibiotic therapy, the disease was progressive. The patient suffered from profound sputum production and hemoptysis. A chest X-ray revealed that the size of the right lung cavitary consolidation had increased, and a new infiltrative shadow appeared in the left lung (Fig. 1B). The patient complained of decreased hearing, leading to a discontinuation of streptomycin treatment. In light of disease progression and the side effects of streptomycin, the patient was re-admitted to the hospital whereupon moxifloxacin (400mg/day) was added to the treatment. The patient's condition improved slightly; however, he eventually underwent right completion pneumonectomy. Pathology specimens revealed a near-totally destroyed lung and severe necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with caseating necrosis. Postoperatively, gradual improvements of the clinical features and radiologic findings were observed, and a negative conversion of sputum examinations was achieved. However, a late bronchopleural fistula developed acutely 47 days postoperatively, and the patient subsequently expired with pneumonia and respiratory failure.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium xenopi in Korea. M. xenopi was clearly shown to be the etiologic agent of the cavitary consolidative changes in our case. Considering clinical and radiographic features, in addition to repeated isolation of M. xenopi, the diagnostic criteria for NTM pulmonary disease were fulfilled.1

M. xenopi is a ubiquitous, thermophilic, slow-growing NTM. This organism is found in freshwater and has been isolated from water samples collected in homes and hospitals.1 M. xenopi appears to have a variable geographic distribution. It has been recovered frequently from clinical specimens in the United Kingdom, northwestern Europe, and Canada; rarely has it been isolated in the U. S. prior to the AIDS epidemic.11 M. xenopi is a very rare pathogen of pulmonary disease in Asian countries, including Japan and Korea. Recently, we reported the clinical significance of NTM isolates from respiratory specimens in Korea.4 In that study, only one of more than 1,500 isolates of NTM from about 800 patients was confirmed to be M. xenopi, and its clinical significance was doubtful.

However, M. xenopi is increasingly recognized as a cause of pulmonary infection. Clinical illness typically presents as an indolent, cavitary lung infection in middle-aged men. Most of those patients have a history of underlying chronic pulmonary disease.1 Conditions predisposing an individual to M. xenopi infection include previously treated pulmonary tuberculosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and a bad postoperative state.5-7,12,13 The classic radiographic appearance of M. xenopi pulmonary disease is a cavitary, apical pulmonary process.5-7,12-14

The optimal therapy and duration of treatment for pulmonary disease secondary to M. xenopi has not been established. Current protocols for M. xenopi infection recommend chemotherapeutic combination with three or four drugs and an overall treatment duration of 18-24 months.1,7,15 The in vitro susceptibility to anti-tuberculosis agents is variable, although enhanced drug activity has been demonstrated with the combination of rifampicin and streptomycin, or rifampicin and ethambutol.16 There was no correlation between treatment outcome and in vitro susceptibility.5 The cornerstone of treatment for M. xenopi infection is currently a combination of rifampicin and ethambutol. Although about 70% of clinical isolates of M. xenopi are resistant to ethambutol, ethambutol is strongly recommended.5 A prospective, randomized study found that the addition of isoniazid is of little or no value in the treatment of M. xenopi infection.5 Some studies of clarithromycin-containing regimens demonstrated good bactericidal activity.17,18 In addition, the successful treatment of M. xenopi infection with a combination of clarithromycin and newer quinolones has also been described.19

The death rate of pulmonary disease secondary to M. xenopi is as high as 70% within five years of onset.5 Although underlying comorbidities might be a major factor determining the death rate, the poor response to antibiotic treatment is alarming. Given the relative ineffectiveness of medical therapy, surgery is an important alternative in patient who can tolerate it.20 Although some investigators have reported success with surgical therapy, others have had disappointing results.6,13

Based on recommended treatment regimens and the results of in vitro susceptibility testing, we initially selected a combination of clarithromycin, rifampicin, ethambutol, and streptomycin for our patient. After four months of antibiotic therapy, moxifloxacin was added due to adverse effects with streptomycin and disease progression. Finally, pulmonary resection was performed. Unfortunately, the patient expired because a bronchopleural fistula developed and led to pneumonia and respiratory failure.

In conclusion, Mycobacterium xenopi is considered to be a cause of pulmonary infection in immunocompetent patients with pre-existing lung disease. This case serves as a reminder to clinicians that the incidence of NTM infection is increasing in Korea, and that unusual NTM organisms are capable of causing disease in non-immunocompromised patients.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the SRC/ERC program of MOST/KOSEF (R11-2002-103)

References

- 1.Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:S1–S25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Lee KS. Diagnosis and treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases: a Korean perspective. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:913–925. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.6.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeon K, Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kim H, et al. Recovery rate of NTM from AFB smear-positive sputum specimens at a medical centre in South Korea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:1046–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Jeon K, Kim TS, Lee KS, Park YK, et al. Clinical significance of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from respiratory specimens in Korea. Chest. 2006;129:341–348. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkins PA, Campbell IA, Research Committee of The British Thoracic Society Pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium xenopi in HIV-negative patients: five year follow-up of patients receiving standardised treatment. Respir Med. 2003;97:439–444. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parrot RG, Grosset JH. Post-surgical outcome of 57 patients with Mycobacterium xenopi pulmonary infection. Tubercle. 1988;69:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(88)90040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simor AE, Salit IE, Vellend H. The role of Mycobacterium xenopi in human disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:435–438. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamazaki Y, Fujiuchi S, Matsumoto H, Takahashi T, Takeda A, Fujita Y, et al. Two cases of pulmonary Mycobacterium xenopi infection. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;41:556–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H, Kim SH, Shim TS, Kim MN, Bai GH, Park YG, et al. PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (PRA)-algorithm targeting 644 bp Heat Shock Protein 65 (hsp65) gene for differentiation of Mycobacterium spp. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;62:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H, Kim SH, Shim TS, Kim MN, Bai GH, Park YG, et al. Differentiation of Mycobacterium species by analysis of the heat-shock protein 65 gene (hsp65) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1649–1656. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falkinham JO., 3rd Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:177–215. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MJ, Citron KM. Clinical review of pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium xenopi. Thorax. 1983;38:373–377. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.5.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banks J, Hunter AM, Campbell IA, Jenkins PA, Smith AP. Pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium xenopi: review of treatment and response. Thorax. 1984;39:376–382. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.5.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittram C, Weisbrod GL. Mycobacterium xenopi pulmonary infection: evaluation with CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:225–228. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199803000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contreras MA, Cheung OT, Sanders DE, Goldstein RS. Pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:149–152. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks J, Jenkins PA. Combined versus single antituberculosis drugs on the in vitro sensitivity patterns of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Thorax. 1987;42:838–842. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.11.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lounis N, Truffot-Pernot C, Bentoucha A, Robert J, Ji B, Grosset J. Efficacies of clarithromycin regimens against Mycobacterium xenopi in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3229–3230. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3229-3230.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majoor CJ, Schreurs AJ, Weers-Pothoff G. Mycobacterium xenopi infection in an immunosuppressed patient with Crohn's disease. Thorax. 2004;59:631–632. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.010546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt H, Schnitzler N, Riehl J, Adam G, Sieberth HG, Haase G. Successful treatment of pulmonary Mycobacterium xenopi infection in a natural killer cell-deficient patient with clarithromycin, rifabutin, and sparfloxacin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:120–124. doi: 10.1086/520140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang-Lazdunski L, Offredo C, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, Danel C, Dujon A, Riquet M. Pulmonary resection for Mycobacterium xenopi pulmonary infection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1877–1882. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]