Abstract

Mid-ventricular obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (MVOHCM) is a rare type of cardiomyopathy, associated with apical aneurysm formation in some cases. We report a patient presenting with ventricular fibrillation, an ECG with an above normal ST segment, and elevated levels of cardiac enzymes but normal coronary arteries. Left ventriculography revealed a left ventricular obstruction without apical aneurysm. There was a significant pressure gradient between the apical and basal sites of the left ventricle. Cine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed on the 10th hospital day, showed asymmetric septal hypertrophy, mid-ventricular obstruction, and an apical aneurysm with a thrombus. The first evaluation by contrast-enhanced imaging showed a subendocardial perfusion defect and delayed enhancement. It was speculated that the intraventricular pressure gradient, due to mid-ventricular obstruction, triggered myocardial infarction, which subsequently resulted in apical aneurysm formation.

Keywords: Mid-ventricular obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Mid-ventricular obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (MVOHCM) is a rare form of cardiomyopathy, characterized by the presence of a pressure gradient between the left ventricular basal and apical chambers, as well as by asymmetric left ventricular hypertrophy. MVOHCM is frequently associated with an apical aneurysm,1-7 but the mechanism of aneurysm formation remains unknown. We describe a patient with MVOHCM in whom the apical aneurysm developed rapidly after an episode of acute myocardial ischemia.

CASE REPORT

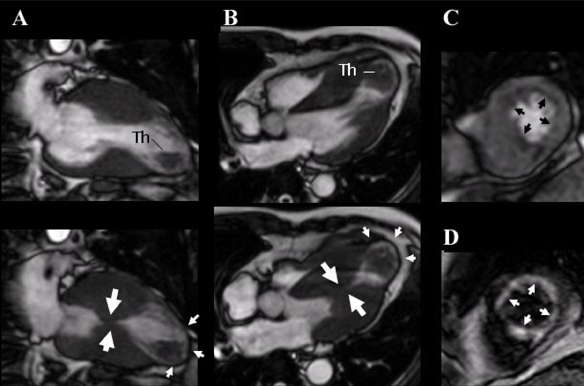

A 58-year-old man presented with ventricular fibrillation. There was no family history of cardiomyopathy or sudden death. After successful defibrillation, his blood pressure was 106/60mmHg, and his pulse rate was 80beats/min. A 12-lead ECG showed ST-segment elevations in leads V3-V6 but no Q waves. Chest X-ray showed no cardiomegaly or pulmonary congestion. Laboratory examination revealed a mild increase in creatine kinase-MB (38mIU/mL) and troponin T (0.3ng/mL) levels. With provisional diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, coronary angiography and left ventriculography were performed. Coronary angiography yielded normal results (Fig. 1A), but the left ventriculogram showed severe left ventricular obstruction during systole with no aneurysmal bulging in the apical segment (Fig. 1B). There was a significant pressure gradient (45mmHg) between the basal and apical sites of the left ventricle at rest (Fig. 2). Using continuous wave Doppler echocardiography, the pressure gradient was measured as 60mmHg. The patient had been diagnosed as having MVOHCM, and medical treatment with a beta blocker and amiodarone was started. ECG-gated, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on the 10th hospital day, using an Intera Achieva (1.5 T, Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands). Cine MRI showed mid-ventricular obstruction and an apical aneurysm with a large thrombus on long-axis (Fig. 3A) and 4-chamber (Fig. 3B) images. Initial gadolinium-diethylenetriomine pentaacetic acid-enhanced imaging showed reduced subendomyocardial perfusion in the mid-ventricular portion of the left ventricle (Fig. 3C). Fifteen minutes later, delayed enhancement of the subendomyocardium was noted (Fig. 3D). Because medical treatment with a beta blocker (carvedilol) did not reduce the intraventricular pressure gradient determined by continuous wave Doppler echocardiography, the patient underwent surgery in which left ventricular aneurysmectomy and removal of the thrombus were performed. The patient received a beta-blocker postoperatively, and the 8-week follow-up period was uneventful.

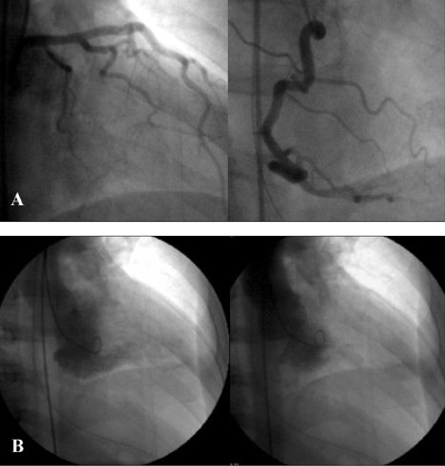

Fig. 1.

(A) Coronary aniogram showing normal left (left panel) and right (right panel) coronary arteries. (B) Left ventriculogram in the 30° right anterior oblique projection, showing a small left ventricular cavity during diastole (left panel) and complete obstruction of the apical site during systole (right panel).

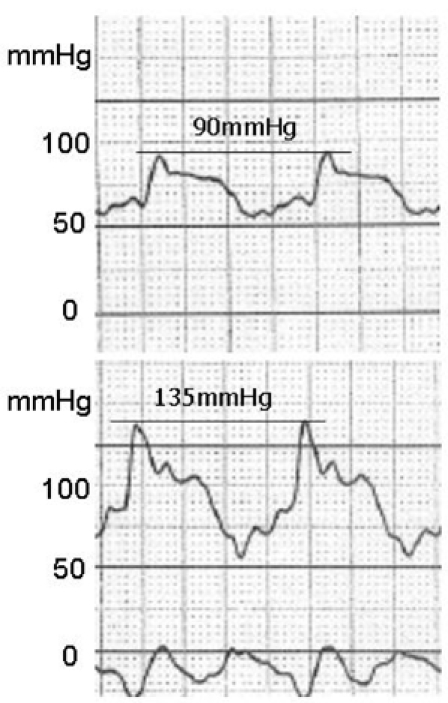

Fig. 2.

Left ventricular pressure in the apex (upper panel) and in the base (lower panel), showing a pressure gradient of 45mmHg

Fig. 3.

ECG-gated, cine magnetic resonance imaging of the long axis (A) and 4-chamber view (B), showing mid-ventricular obstruction during systole (large arrows) (lower panels), an apical aneurysm (small arrows), and a thrombus (Th, upper panels) during diastole. Contrast-enhanced first-pass myocardial perfusion (C) and delayed enhancement (D) images, showing a subendomyocardial perfusion defect (arrows) and delayed enhancement (arrows), respectively.

DISCUSSION

MVOHCM is a rare form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, characterized by the presence of a pressure gradient between the apical and basal chambers of the left ventricle. It is frequently associated with an apical aneurysm without significant atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.1-7 The mechanisms responsible for apical aneurysm formation are not well understood. Major causes of aneurysm formation that have been proposed are increased afterload and high apical pressure, resulting from mid-ventricular obstruction, which lead to compression of the intramyocardial coronary arteries and/or greater oxygen demand due to increased myocardial thickness and decreased oxygen supply due to the decreased capillary network.7 In addition, the apex is subject to greater and sustained systolic stress due to the high pressure gradient. In two cases, Maron et al. discovered extremely high pressure in the apex (260mmHg and 225mmHg)8. However, in the present case, the peak systolic pressure in the apex was 135mmHg, which might not be sufficient to cause aneurysmal bulging. Furthermore, apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may show a myocardial perfusion defect in the apex on stress images even in the absence of epicardial coronary artery obstruction, suggesting decreased coronary flow reserve in the hypertrophic apical segment.9 One limitation of our report is that we do not have evidence of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in our patient prior to the acute ischemic event. The process of aneurysm formation has been believed to occur over a long period of time due to predisposing ischemic episodes resulting from a chronic increase of systolic wall stress.7,10,11 However, the present case involved rapid aneurysm development within 10 days after the acute ischemic episode. A left ventriculogram showed no aneurysm, and the increase in cardiac enzyme levels was mild in the acute phase, whereas MRI performed after 10 days revealed extensive myocardial necrosis at the site of the apical aneurysm. Thus, it was hypothesized that the initially small infarction arose in the apex as a result of compression of intramyocardial coronary arteries and/or oxygen supply-demand imbalance and expanded rapidly because of the further increase in systolic wall stress due to the sustained pressure gradient.

Management of MVOHCM is obscure because it may result in life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias4 and sudden death.5 Generally, beta blockers are the first choice of treatment for patients with subaortic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,12 but the optimal treatment for MVOHCM has not yet been established. Dual-chamber pacing13,14 and percutaneous myocardial ablation6,15 have been proposed as non-surgical treatments, but their long-term prognosis and procedural safety await further observation with a large patient population.

In conclusion, our case demonstrated that apical aneurysm may develop rapidly after an episode of acute myocardial ischemia in patients with MVOHCM. Acute increase in the intraventricular pressure gradient was thought to be the major cause of apical aneurysm formation.

References

- 1.Akutsu Y, Shinozuka A, Huang TY, Watanabe T, Yamada T, Yamanaka H, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with apical left ventricular aneurysm. Jpn Circ J. 1988;62:127–131. doi: 10.1253/jcj.62.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin CS, Chen CH, Ding PY. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 1998;64:305–307. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(98)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harada K, Shimizu T, Sugishita Y, Yao A, Suzuki J, Takenaka K, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with midventricular obstruction and apical aneurysm: a case report. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:915–919. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito N, Suzuki M, Enjoji Y, Nakamura M, Namiki A, Hase H, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with mid-ventricular obstruction complicated with apical left ventricular aneurysm and ventricular tachycardia: a case report. J Cardiol. 2002;39:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tse HF, Ho HH. Sudden cardiac death caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with midventricular obstruction and apical aneurysm. Heart. 2003;89:178. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tengiz I, Ercan E, Türk UO. Percutaneous myocardial ablation for left mid-ventricular obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2006;22:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s10554-005-5295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsubara K, Nakamura T, Kuribayashi T, Azuma A, Nakagawa M. Sustained cavity obliteration and apical aneurysm formation in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00576-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron BJ, Hauser RG, Roberts WC. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular apical diverticulum. Am J Cardiol. 1999;77:1263–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward RP, Pokharna HK, Lang RM, Williams KA. Resting "Solar Polar" map pattern and reduced apical flow reserve: characteristics of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy on SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2003;10:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(03)00455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fighali S, Krajcer Z, Edelman S, Leachman RD. Progression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy into a hypokinetic left ventricle: higher incidence in patients with midventricular obstruction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9:288–294. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura T, Matsubara K, Furukawa K, Azuma A, Sugihara H, Katsume H, et al. Diastolic paradoxic jet flow in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: evidence of concealed apical asynergy with cavity obliteration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:516–524. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maron BJ, Casey SA, Poliac LC, Gohman TE, Almquist AK, Aeppli DM. Clinical course of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a regional United States cohort. JAMA. 1999;281:650–655. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maron BJ, Nishimura RA, McKenna WJ, Rakowski H, Josephson ME, Kieval RS. Assessment of permanent dual-chamber pacing as a treatment for drug-refractory symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A randomized, double-blind, crossover study (M-PATHY) Circulation. 1999;99:2927–2933. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.22.2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe H, Kibira S, Saito T, Shimizu H, Abe T, Nakajima I, et al. Beneficial effect of dual-chamber pacing for a left mid-ventricular obstruction with apical aneurysm. Circ J. 2002;66:981–984. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seggewiss H, Faber L. Percutaneous septal ablation for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and mid-ventricular obstruction. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2000;1:277–280. doi: 10.1053/euje.2000.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]