Abstract

A 70-year-old man with past history of hemicolectomy due to colon cancer underwent a follow-up abdominal/pelvic CT scan. CT revealed a right adrenal metastasis and then he underwent FDG-PET/CT study to search for other possible tumor recurrence. In PET images, other than right adrenal gland, there was an unexpected intense FDG uptake at right inguinal region and at first, it was considered to be an inguinal metastasis. However, correlation of PET images to concurrent CT data revealed it to be a bladder herniation. This case provides an example that analysis of PET images without corresponding CT images can lead to an insufficient interpretation or false positive diagnosis. Hence, radiologists should be aware of the importance of a combined analysis of PET and CT data in the interpretation of integrated PET/CT and rare but intriguing conditions, such as bladder herniation, during the evaluation of PET scans in colon cancer patients.

Keywords: Bladder hernia, inguinal, bladder, FDG-PET, PET/CT imaging

INTRODUCTION

Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) plays an important role in the detection and assessment of recurrent colorectal cancer.1,2 FDG-PET has an overall detection sensitivity of over 90%, but specificity may be only approximately 70%.2,3 There are several common causes of false-positive diagnoses associated with FDG-PET, namely, the normal physiologic uptake of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract and benign infectious or inflammatory lesions.2,4 To avoid false-positive diagnoses, careful correlation with anatomy from CT analysis is often necessary. Current PET/CT system have demonstrated to improve the diagnostic accuracy for recurrent colorectal cancer compared to PET imaging alone.4 In this report, we present the case of an inguinal hernia of the bladder that was correctly diagnosed by combined review of PET/CT, but initially simulated nodal recurrence during the first, isolated interpretation of PET.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old man with a history of extended right hemicolectomy due to adenocarcinoma of the ascending colon was assessed every 6 months for evaluation of tumor recurrence. At the 12-month follow up abdomen/pelvic CT scan showed a new solid mass arising from the right adrenal gland that appeared as an adrenal metastasis and the patient underwent FDG PET/CT studies in order to detect any other recurrent lesions.

PET/CT studies were performed using the GEMINI Dual PET-CT scanner (Philips Medical systems). The GEMINI Dual scanner is an open PET-CT system that combines a helical dual slice CT with a 3D PET scanner equipped with its own transmission source. Patients are scanned 1 hour after injection of 0.14mCi/Kg FDG. At first, the PET emission scan is obtained without the low-dose CT. The emission scan consists of 9 bed positions of 2 minutes 30 seconds each, covering 85.2cm, followed by the Cs-137 transmission scan. The high activity of the Cs-137 source (10 mCi with a half-life of 30 years) and the detection of a single event allows for a fast transmission scan. The total duration of the Cs-137 transmission scan is approximately 1 minute (100cm scan length). A diagnostic high dose CT scan was performed (scan field of 500mm, increment of 3mm, slice thickness 3.0 mm, pitch of 1.5 second per rotation, matrix 512 × 512, 120KV, 450mAs) after an automated intravenous injection of 120mL of a low osmolar, nonionic, iodinated contrast agent (2cc/Kg, Omnipaque, Amersham health). The total acquisition time of the PET/CT was 35 minutes.

For the PET, patients fasted at least 6 hours before the intravenous injection of 18F-FDG,with scanning beginning 60 minutes afterwards. Images from the neck to the proximal thigh were obtained on an Allegro PET scanner (Philips-ADAC Medical Systems), with a spatial resolution of 5.3mm in the center of the field of view. The Allegro acquired data in the 3D mode after administration of 5.18MBq (0.14mCi)/kg of 18F-FDG. Transmission scans (2 minutes 30 seconds per bed position) to correct for non-uniform attenuation were obtained using 137Cs point sources. Transmission scans were interleaved between the multiple emission scans. The images were reconstructed using an iterative reconstruction algorithm, the low-action maximal-likelihood algorithm.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis was performed on HiSpeed CT (GE Medical System) using a slice thickness of 7mm, with 200mA and 120 kvp.

Our institute used the same algorithm for analyzing the PET/CT scans. Initially, PET images were read independently from CT images. Evaluation of PET images included only attenuation-corrected images. The interpretation of a lesion as benign or malignant was based primarily on a visual analysis. SUVmaxs served solely as guidance. After the PET reviews, a combined review of PET and CT images was performed. Lesions classified as malignant by the PET maintained a malignant status when the corresponding CT image revealed a morphologic correlation, for example, lymph node abnormality. Any abnormality on the CT without a corresponding increased 18F-FDG uptake was interpreted as nonmalignant. The results presented are based primarily on the information provided by the PET, and the CT was used for exact anatomic localization.

In our patient, PET images showed an intense FDG uptake in the right adrenal gland corresponding to the lesion previously detected on the abdomen/pelvis CT. In addition, an unexpected intense FDG uptake was seen in the right inguinal region and was considered to be an inguinal lymph node metastasis (Fig. 1). Ultrasound had been performed for further evaluation of the right inguinal region. However, this did not reveal an abnormal solid mass corresponding to the region of FDG uptake in PET, but only multiple small benign lymph nodes which were less than 1cm in size with fatty hila.

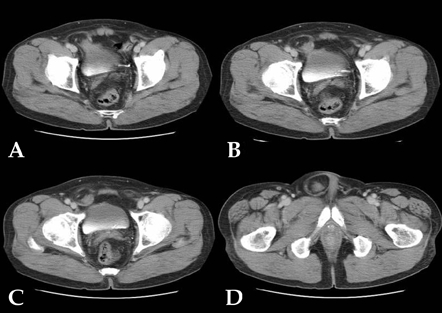

Fig. 1.

Serial axial (A) and coronal (B) FDG PET showed an unexpected an intense FDG uptake in right inguinal region, which was considered to be inguinal nodal metastasis (arrows).

Subsequently, the PET/CT images were retrospectively reviewed together with the relevant CT anatomic data, specifically focused on the inguinal region. The lesion with intense FDG uptake was interpretated as a herniation of the right anterior wall of the bladder into the right inguinal canal. And then, initial abdomen/pelvis CT scan was reviewed, and the inguinal mass was revelaed to be a herniation of the bladder rather than metastasis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Initial abdomen/pelvis CT showed that the right anteroinferior wall of bladder was herniated into the right inguinal canal without contrast enhancement within the herniated sac. The neck of the hernial sac was relatively wide (A and B) and within the hernial sac there was homogeneous cystic low density due to trapped urine without calcification (C and D).

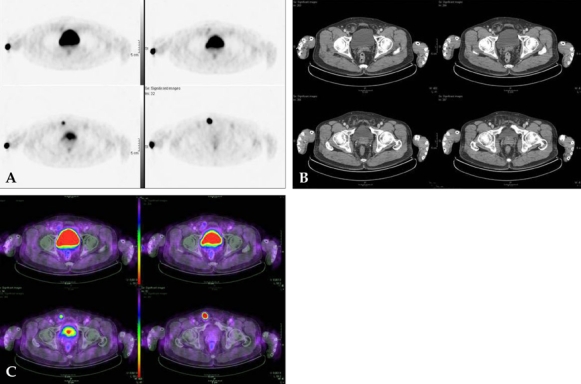

We retrospectively evaluated the 18FDG uptake by semiquantitative analysis using the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) for each focus of adrenal metastasis, urinary bladder, hernia and ureter. SUVmax was 9.3 for adrenal metastasis, 33.8 for urinary bladder, 28.6 for hernial segment, and 1.2 for focal faint radiotracer uptake in the right ureter. The high SUVmax in the bladder and hernia was explained by accumulated intense radiotracer activity by urinary excretion of FDG.

It was later confirmed the patient had suffered for 30 years from a herniation in the inguinal area that often extended to the scrotal region when he walked for long periods. The herniated segments were easily reduced by manual assistance and by changing positions from standing to supine. The patient was asymptomatic and had no difficulty in micturition even during the herniated status. The patient had been treated with chemotherapy for tumor recurrence without herniorrhaphy.

DISCUSSION

Bladder hernia represents 0.5% to 3% of all lower abdominal hernias and is most prevalent among men between 50 and 70 years of age5 and the bladder is involved in approximately 1% to 4% of all inguinal hernias.6 Bladder hernias rarely have clinical sequelae and are usually found incidentally in imaging studies or during inguinal hernia repair.7

Most patients with bladder hernia are asymptomatic and in symptomatic patients, the most frequent clinical findings are two-phase or double micturition.8 The patient described here has no difficulty with urination and did not suffer two-phase micturition, which was likely due to the relatively wide neck of the herniated segment of bladder. Sixteen percent of bladder herniations are diagnosed postoperatively with intraoperative bladder injury during the repair of an inguinal hernia8 thus it is important to recognize the presence of bladder herniation preoperatively. Hernias involving the bladder are usually a direct type, as in this case9 and typical radiological findings include abnormal localization of the herniated structures and asymmetry, protrusion of the ureter outside the pelvic bones, and indentation of the bladder wall.10

In the presented case, a bladder hernia presented as a region of intense FDG uptake in the right inguinal area simulating inguinal metastasis. Pirson et al.11 reported a similar case of a 67-year-old man with cerebral metastasis where, in order to determine the primary focus, the patient underwent an FDG PET that showed increased FDG uptake in the brain, right colon, and in the inguinal region. While the increased FDG uptake in the brain corresponded to the cerebral metastasis, a CT scan revealed that the inguinal uptake was due to an inguinal hernia.

Caution is also required in the interpretation of FDG PET images in patients who have undergone pelvic surgery in order to avoid interpreting the alterations of normal pelvic anatomy as pathologic lesions. During the detection of pelvic recurrence in patients with rectal cancer who underwent abdominoperineal or anterior resection, thirteen (35%) of the 37 pelvic sites of 18F FDG uptake were either false-positive or equivocal using only PET. This rate was reduced by the integrated examination of the PET/CT.4 It has been reported that combined PET/CT imaging increases the accuracy and certainty of locating lesions in colorectal cancer when compared with PET alone.12

Our case report demonstrates the possibility of misinterpreting PET images without combining relevant CT data. We routinely examine the CT data of the PET/CT scan together with the PET data. However, in this case we hastily classified the inguinal hot uptake as malignant using only the PET image before applying a morphologic correlation with the corresponding CT image. The patient had a previous history of colon cancer, and the inguinal region is a common site of lymph node metastasis. In this case, we realized that a combined review of PET and CT data is important in any situation. A proper interpretation of PET/CT implies a combined PET and CT data analysis, while keeping in mind the possible inaccuracies of FDG uptake location generated by peristaltic motions occurring between CT and PET image acquisitions.13

In conclusion, this report describes a case in which an inguinal hernia of a portion of the bladder wall simulated a nodal recurrence of colon cancer, as determined by PET imaging. Concurrent interpretation of the PET with the corresponding CT data revealed the correct diagnosis. It is important that radiologists remain aware of this rare condition during the evaluation of PET scans for colorectal cancer. Furthermore, this case demonstrates the importance of a combined analysis of PET and CT data in the interpretation of integrated PET/CT.

Fig. 3.

Starting from the top, PET (A), CT (B) and fusion images (C) were seen. Intense FDG uptake in right inguinal region resulted from accumulation of FDG in the trapped urine of hernial segment of bladder.

References

- 1.Hustinx R. PET imaging in assessing gastrointestinal tumors. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:1123–1139. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delbeke D, Martin WH. PET and PET-CT for evaluation of colorectal carcinoma. Semin Nucl Med. 2004;34:209–223. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huebner RH, Park KC, Shepherd JE, Schwimmer J, Czernin J, Phelps ME, et al. A meta-analysis of the literature for whole-body FDG PET detection of recurrent colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1177–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Even-Sapir E, Parag Y, Lerman H, Gutman M, Levine C, Rabau M, et al. Detection of recurrence in patients with rectal cancer: PET/CT after abdominoperineal or anterior resection. Radiology. 2004;232:815–822. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323031065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conde Sánchez JM, Espinosa Olmedo J, Salazar Murillo R, Vega Toro P, Amaya Gutiérrez J, Alonso Flores J, et al. Giant inguino-scrotal hernia of the bladder. Clinical case and review of the literature. Actas Urol Esp. 2001;25:315–319. doi: 10.1016/s0210-4806(01)72623-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koontz AR. Sliding hernia of diverticulum of bladder. AMA Arch Surg. 1955;70:436–438. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1955.01270090114025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher PC, Hollenbeck BK, Montgomery JS, Underwood W., 3rd Inguinal bladder hernia masking bowel ischemia. Urology. 2004;63:175–176. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciancio G, Burke GW, Nery J, Huson H, Coker D, Miller J. Positional obstructive uropathy secondary to ureteroneocystostomy herniation in a renal transplant recipient. J Urol. 1995;154:1471–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catalano O. Computed tomography findings in scrotal cystocele. Eur J Radiol. 1995;21:126–127. doi: 10.1016/0720-048x(95)00715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andac N, Baltacioğlu F, Tüsney D, Cimşit NC, Ekinci G, Biren T. Inguinoscrotal bladder herniation: is CT a useful tool in diagnosis? Clin Imaging. 2002;26:347–348. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(02)00447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirson AS, Krug B, Lacrosse M, Luyx D, Barbeaux A, Borght TV. Bladder hernia simulating metastatic lesion on FDG PET study. Clin Nucl Med. 2004;29:767. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200411000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohade C, Osman M, Leal J, Wahl RL. Direct comparison of (18)F-FDG PET and PET/CT in patients with colorectal carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1797–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutman F, Alberini JL, Wartski M, Vilain D, Le Stanc E, Sarandi F, et al. Incidental colonic focal lesions detected by FDG PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:495–500. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]