Abstract

We examined trends in utilization of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), THA, and hemiarthroplasty (HA) for femoral neck fractures. Closed femoral neck fractures managed with ORIF or hip arthroplasty (n = 162,257) were extracted from 1990 to 2001 Nationwide Inpatient Samples. Trends were examined during three periods (1990–1993 [Period I], 1994–1997 [Period II], and 1998–2001 [Period III]). Utilization of HA increased from 67.8% in Period I to 75.3% in Period III. In the same period, utilization of THA decreased from 11.6% to 6.6%. The trend of decreased use of THA was consistent regardless of age, hospital, or surgeon volume. In Period III, 28.7% of patients were managed at urban teaching hospitals as compared with 19.6% in Period I. Increased utilization of HA conforms with recent evidence that arthroplasty has better outcomes than ORIF. However, the decrease in THA is contrary to what was expected, and its impact on patient outcomes needs to be evaluated. The increase in the proportion of femoral fractures managed at urban teaching hospitals may reflect a change in the organization of trauma systems during the last decade.

Level of Evidence: Level II, diagnostic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Fractures of the femoral neck are common, disabling, and expensive [19]. They rarely are managed nonoperatively, and this generally occurs only when the patient or family choose to initiate comfort measures only. Surgical management options for femoral neck fractures include ORIF, HA, and THA [5, 15].

Although there is debate regarding the preferred procedure for management of displaced femoral neck fractures, recent studies suggest arthroplasty has better outcomes as compared with ORIF [7, 8, 14, 22], and one report suggests THA may have better outcomes as compared with HA in elderly patients [14]. However, in many patients, THA can be more technically challenging owing to the nature of the fracture. In patients without fractures, THA has optimal outcomes when performed by surgeons who perform a high-volume of arthroplasties [3, 12, 13, 16]. In situations when arthroplasty is the optimal management, other factors such as surgeons’ technical expertise, surgeons’ annual THA or HA volume, and variation in practice patterns across hospitals also may play a role in surgical decision-making.

Thus, the best choice of surgical procedure for hip fracture is complex and evolving. Numerous studies have provided evidence for better outcomes after arthroplasty (HA or THA) as compared with ORIF [4, 7, 10, 11, 17, 20–22]. However, there are no established clinical guidelines for indications and choice of surgical procedures for patients with femoral neck fractures. To gain insight into this clinical choice, it would be useful to determine trends in utilization of procedures performed for patients with femoral neck fractures in actual clinical practice across the United States and assess whether these trends conform to recent evidence in the literature. It would be helpful for clinicians and policymakers to determine whether these trends are influenced by patient, hospital, and surgeon characteristics.

Therefore, we examined trends in relative utilization of ORIF, HA, and THA for closed femoral neck fractures during the last decade in the United States. We also assessed whether utilization trends varied by three provider characteristics: hospital volume, hospital location, and surgeon volume.

Materials and Methods

We used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample databases for 1990 through 2001. The Nationwide Inpatient Sample is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [1]. The Nationwide Inpatient Sample is the largest all-payer inpatient care database publicly available in the United States and contains between five and eight million records of inpatient stays per year from approximately 1000 hospitals. This represents a 20% stratified sample of community hospitals in the United States [1]. To ensure maximal representation of US hospitals, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample included hospitals according to five important hospital characteristics: geographic region (Northeast, North Central, West, South); ownership (public, private not-for-profit, private investor-owned); location (urban, rural); teaching status (teaching hospital, nonteaching hospital); and bed size (small, medium, large). Additional details on these variables can be found at the HCUP web site [1].

The HCUP assigned validation and quality assessment of these data sets to an independent contractor [2]. The Nationwide Inpatient Sample also was validated extensively against the National Hospital Discharge Survey and confirmed to perform well for many estimates [23].

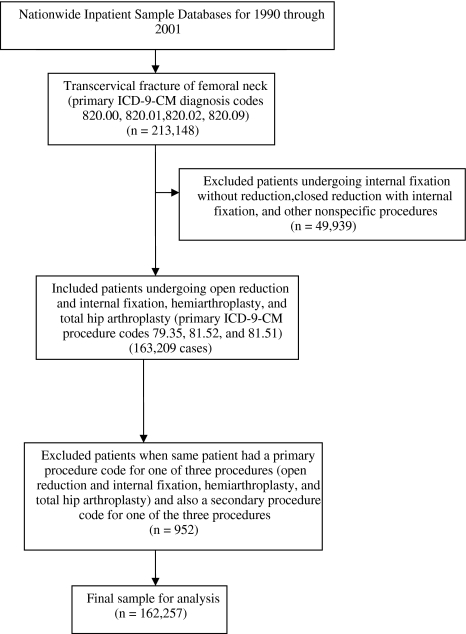

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample database contains information on primary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes and 14 secondary diagnoses and procedure codes for each patient record. Each record in the data set represents one patient admission and has a unique identification number. We selected admissions with an ICD-9-CM primary diagnosis code for closed transcervical fracture of femoral neck (820.00, 820.01, 820.02, 820.09). We included patients in whom ORIF (79.35), HA (81.52), or THA (81.51) was designated as the primary procedure code, which represented a majority of patients (n = 163,209 of 164,093 patients with femoral neck fractures; 99.5% of patients). Other procedures such as internal fixation without reduction (including prophylactic internal fixation of bone, reinsertion of fixation device, revision of broken or displaced fixation device; n = 13,307) and closed reduction with internal fixation (n = 12,654) were used in fewer patients. We also did not include patients with closed base of femoral neck fractures because their management is different from that of patients with other femoral neck fractures (n = 13,058). Records in which the same patient had a primary procedure code for one of the three procedures (ORIF, HA, or THA) and also a secondary procedure code for one of the three procedures also were not included (n = 952). Our final analysis included 162,257 patients who had surgical repair of a closed transcervical femoral neck fracture between 1990 and 2001 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The case inclusion schema is shown for patients with femoral neck fractures undergoing HA, THA, or ORIF. ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification.

We grouped the admissions into the three periods: Period I (1990–1993), Period II (1994–1997), and Period III (1998–2001), creating approximately equal intervals. Patient race-ethnicity was categorized in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample databases as white, black, Hispanic, and other (including Asian or Pacific Islander and Native American). The category “black” may include African-American and Caribbean-American patients. We categorized age into younger than 50, 50 to 64, 65 to 79, and 80 years or older based on distribution of procedure utilization within age groups. A majority of patients managed surgically for femoral neck fractures were female (75% to 78% in Periods I through III), white (91% to 94% in Periods I through III), and in age groups of 65 to 79 and 80 years or older (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients managed surgically, 1990–2001

| Characteristics | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1993 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2001 | |

| (Period I) | (Period II) | (Period III) | |

| (n = 47,435) | (n = 59,269) | (n = 55,553) | |

| Number (percentage of patients) | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| Younger than 50 | 849 (1.8) | 1011 (1.7) | 993 (1.8) |

| 50–64 | 2644 (5.6) | 2981 (5.0) | 2939 (5.3) |

| 65–79 | 17,366 (36.6) | 20,348 (34.3) | 18,131 (32.6) |

| 80 or older | 26,473 (55.8) | 34,919 (58.9) | 33,489 (60.3) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 36,828 (77.6) | 45,550 (76.9) | 42,132 (75.8) |

| Male | 10,607 (22.4) | 13,716 (23.1) | 13,419 (24.2) |

| Race* | |||

| White | 25,166 (94.2) | 45,591 (92.9) | 40,538 (91.1) |

| Black | 638 (2.4) | 1585 (3.2) | 1595 (3.6) |

| Hispanic | 586 (2.2) | 1284 (2.6) | 1400 (3.1) |

| Other† | 335 (1.3) | 638 (1.3) | 986 (2.2) |

| Hospital bed size | |||

| Small | 4,594 (9.7) | 9,018 (15.2) | 7,848 (14.1) |

| Medium | 13,695 (29.0) | 19,199 (32.5) | 15,966 (28.8) |

| Large | 29,025 (61.4) | 30,956 (52.3) | 31,687 (57.1) |

| Location and teaching status of hospital | |||

| Rural | 7587 (16.0) | 10,492 (17.7) | 11,180 (20.1) |

| Urban nonteaching | 30,442 (64.2) | 35,945 (60.7) | 28,395 (51.1) |

| Urban teaching | 9285 (19.6) | 12,736 (21.5) | 15,926 (28.7) |

| Hospital annual THA volume | |||

| 0 | 1326 (2.8) | 1249 (2.1) | 921 (1.7) |

| 1–24 | 13,727 (28.9) | 15,390 (26.0) | 13,494 (31.7) |

| 25–99 | 22,787 (48.0) | 29,642 (50.1) | 26,328 (47.4) |

| 100–199 | 7366 (15.5) | 10,431 (17.6) | 11,597 (20.9) |

| 200 or more | 2229 (4.7) | 2557 (4.3) | 3213 (5.8) |

| Hospital annual HA volume | |||

| 0 | 198 (0.4) | 75 (0.1) | 74 (0.1) |

| 1–14 | 7638 (16.1) | 6667 (11.3) | 5807 (10.5) |

| 15–25 | 7636 (16.1) | 8022 (13.5) | 8393 (15.1) |

| 25–100 | 30,110 (63.5) | 40,170 (67.8) | 36,667 (66.0) |

| 100 or more | 1853 (3.9) | 4335 (7.3) | 4612 (8.3) |

| Surgeon annual THA volume | |||

| 1–9 | 12,529 (26.4) | 18,543 (31.3) | 12,305 (22.2) |

| 10–19 | 4781 (10.1) | 7622 (12.9) | 5385 (9.7) |

| 20–497 | 2665 (5.6) | 4231 (7.1) | 2567 (4.6) |

| 50 or more | 485 (1.0) | 803 (1.4) | 764 (1.4) |

| Not reported | 26,975 (56.9) | 28,070 (47.4) | 34,532 (62.2) |

| Surgeon annual HA volume | |||

| 1–4 | 7198 (15.2) | 10,534 (17.8) | 7314 (13.2) |

| 5–9 | 8590 (18.1) | 11,729 (19.8) | 8685 (15.6) |

| 10–20 | 5868 (12.4) | 10,820 (18.3) | 6825 (12.3) |

| 20 or more | 1402 (3.0) | 3343 (5.6) | 2154 (31.2) |

| Not reported | 24,377 (51.4) | 22,843 (38.5) | 30,575 (55.0) |

Overall missing for age n = 114 (0.1%); for gender n = 5 (0.0%); for hospital bed size n = 269 (0.2%); for location and teaching status of hospital n = 269 (0.2%); *as a result of a high percentage missing for race (43.7% for 1990–1993; 17.2% for 1994–1997; and 19.9% for 1998–2001), percentages are expressed as those of data excluding missing values; †other includes Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, and other.

Hospital teaching status for a given year was obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey by the HCUP. A hospital was considered a teaching hospital if it had an American Medical Association-approved residency program, was a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals, or had a ratio of full-time-equivalent interns and residents to beds of 0.25 or greater. We characterized hospitals as urban if they were in a metropolitan statistical area and rural if they were in a nonmetropolitan statistical area. We calculated hospital volume per year for THA and HA separately using unique hospital identifiers provided in the databases. This was performed by looking at all THA and HA procedures performed by a given hospital in the entire Nationwide Inpatient Sample data sets. Thus, THA and HA annual volumes were calculated for each of these respective procedures performed in a hospital for any indication (and not only for femoral neck fractures). Annual hospital volume of THA was divided into zero procedures, one to 24 procedures, 25 to 99 procedures, 100 to 199 procedures, and 200 or more procedures; and that of HA was divided into zero procedures, one to 14 procedures, 15 to 25 procedures, 25 to 100 procedures, and 100 or more procedures. This was based on the distribution of procedure utilization in our patient population. Annual THA and HA surgeon volume was calculated in a similar way. Because surgeon identifiers were missing in 46% of patient records, we could not determine whether a surgeon did not perform any THAs or HAs in a year or the information was missing. Therefore, for records with available surgeon identifiers, we divided annual surgeon volume of THA into one to nine procedures, 10 to 19 procedures, 20 to 49 procedures, and 50 or more procedures; and that of HA was divided into one to four procedures, five to nine procedures, 10 to 20 procedures, and 20 or more procedures. We performed analyses to determine if surgeon identifier was especially likely to be missing in particular patient or provider groups. These analyses indicated the missing data were distributed evenly across patient and hospital characteristics.

We described patient demographics, surgeon characteristics, and hospital characteristics across periods using proportions. The overall association between times and the distribution of ORIF, HA, and THA utilization was examined using the chi square test of independence. Additional analyses focused on identification of factors influencing the association between times and the distribution of ORIF, HA, and THA. Factors considered were age, hospital volume, and surgeon volume. We performed statistical analyses using Intercooled STATA for Windows (version 8.2; Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and SAS for Windows (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

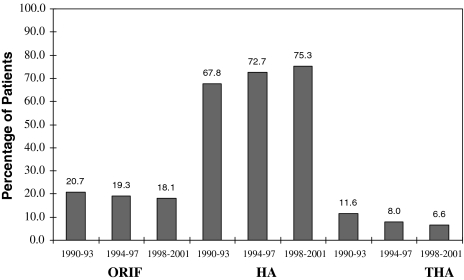

Overall, the proportion of patients undergoing HA increased from 67.8% in Period I to 75.3% in Period III (Fig. 2). However, the proportion of patients undergoing THA diminished (p < 0.001) from 11.6% in Period I to 6.6% in Period III. When stratified by age, a majority of patients younger than 50 years underwent ORIF in all three periods (Table 2). Hemiarthroplasty was performed in a majority of patients in the 65 to 79 years (67.1% to 75.2% between Periods I and III) and 80 years or older (71.6% to 78.5% between Periods I and III) age groups. The proportion of patients undergoing HA in these age groups increased (p < 0.001) steadily between Periods I and III (from 67.1% to 75.2% in patients 65 to 79 years and from 71.6% to 78.5% in patients of 80 years or older). However, we observed an overall trend of a declining proportion (p < 0.001) of patients undergoing THA with time across all age groups.

Fig. 2.

Temporal trends in increased utilization of HA and decreased utilization of THA for surgical management of femoral neck fractures are shown. ORIF = open reduction and internal fixation.

Table 2.

Temporal trends in surgical management by age, 1990–2001

| Surgical procedure by age* | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1993 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2001 | |

| (Period I) | (Period II) | (Period III) | |

| (n = 47,435) | (n = 59,269) | (n = 55,553) | |

| Number (percentage of patients) | |||

| Younger than 50 years | |||

| ORIF | 657 (77.4) | 759 (75.1) | 776 (78.2) |

| HA | 153 (18.0) | 212 (21.0) | 188 (18.9) |

| THA | 39 (4.6) | 40 (4.0) | 29 (2.9) |

| 50–64 years | |||

| ORIF | 1041 (39.4) | 1059 (35.5) | 933 (31.8) |

| HA | 1293 (48.9) | 1624 (54.5) | 1745 (59.4) |

| THA | 310 (11.7) | 298 (10.0) | 261 (8.9) |

| 65–79 years | |||

| ORIF | 3571 (20.6) | 3955 (19.4) | 3214 (17.7) |

| HA | 11,651 (67.1) | 14,490 (71.2) | 13,642 (75.2) |

| THA | 2144 (12.4) | 1903 (9.4) | 1275 (7.0) |

| 80 years or older | |||

| ORIF | 4524 (17.1) | 5678 (16.3) | 5116 (15.3) |

| HA | 18,963 (71.6) | 26,773 (76.7) | 26,280 (78.5) |

| THA | 2986 (11.3) | 2468 (7.1) | 2093 (6.3) |

*Overall missing for age n = 114 (0.1%).

We found a decline (p < 0.001) in utilization of THA across all hospital volume categories (Table 3). In hospitals with an annual THA volume of 200 or more procedures, THA was performed in 18.8% of patients in Period I and 8.9% of patients in Period III. In hospitals with annual THA volumes of one to 24 procedures, 8.6% of patients received THA in Period I and 5.7% in Period III. Similar trends were observed in distribution of procedures across surgeon THA volume categories (data not shown because this analysis was exploratory as a result of missing data on surgeon identifiers). An increasing proportion (p < 0.001) of patients were managed at urban teaching hospitals in the later periods (28.7 in Period III as compared with 19.6 in Period I). The distribution of missing surgeon identifiers was similar across hospital and patient characteristics. Surgeons performing 50 or more THAs per year used THA in 27.0% of their patients in Period I as compared with 16.9% in Period III. During the same period, surgeons with annual THA volumes of one to nine procedures used THA in 10.0% of their patients in Period I as compared with 7.7% in Period III. The proportion of patients managed across hospital and surgeon volume categories remained consistent throughout the three periods with most procedures being performed by low- to medium-volume providers.

Table 3.

Temporal trends in surgical management by hospital and surgeon volume, 1990–2001

| Annual volume | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1993 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2001 | |

| (Period I) | (Period II) | (Period III) | |

| (n = 47,435) | (n = 59,269) | (n = 55,553) | |

| Number (percentage of patients) | |||

| Hospital THA | |||

| 0 | |||

| ORIF | 194 (14.6) | 224 (17.9) | 179 (19.4) |

| HA | 1132 (85.4) | 1025 (82.1) | 742 (80.6) |

| THA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1–24 | |||

| ORIF | 3045 (22.2) | 3057 (19.9) | 2414 (17.9) |

| HA | 9497 (69.2) | 11,351 (73.8) | 10,309 (76.4) |

| THA | 1185 (8.6) | 982 (6.4) | 771 (5.7) |

| 25–99 | |||

| ORIF | 4670 (20.5) | 5637 (19.0) | 4670 (17.7) |

| HA | 15,445 (67.8) | 21,562 (72.7) | 19,945 (75.8) |

| THA | 2672 (11.7) | 2443 (8.2) | 1713 (6.5) |

| 100–199 | |||

| ORIF | 1362 (18.5) | 2029 (19.5) | 2146 (18.5) |

| HA | 4792 (65.1) | 7477 (71.7) | 8563 (73.8) |

| THA | 1212 (16.5) | 925 (8.9) | 888 (7.7) |

| 200 or more | |||

| ORIF | 533 (23.9) | 505 (19.8) | 630 (19.6) |

| HA | 1278 (57.3) | 1693 (66.2) | 2297 (71.5) |

| THA | 418 (18.8) | 359 (14.0) | 286 (8.9) |

| Hospital HA | |||

| 0 | |||

| ORIF | 89 (45.0) | 41 (54.7) | 40 (54.1) |

| HA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| THA | 109 (55.1) | 34 (45.3) | 34 (46.0) |

| 1–14 | |||

| ORIF | 1772 (23.2) | 1558 (23.4) | 1244 (21.4) |

| HA | 4357 (57.0) | 4162 (62.4) | 3945 (67.9) |

| THA | 1509 (19.8) | 947 (14.2) | 618 (10.6) |

| 15–25 | |||

| ORIF | 1649 (21.6) | 1606 (20.0) | 1569 (18.7) |

| HA | 4895 (64.1) | 5682 (70.8) | 6188 (73.7) |

| THA | 1092 (14.3) | 734 (9.2) | 636 (7.6) |

| 25–99 | |||

| ORIF | 6006 (20.0) | 7494 (18.7) | 6483 (17.7) |

| HA | 21,420 (71.1) | 29,891 (74.4) | 28,042 (76.5) |

| THA | 2684 (8.9) | 2785 (6.9) | 2142 (5.8) |

| 100 or more | |||

| ORIF | 288 (15.5) | 753 (17.4) | 703 (15.2) |

| HA | 1472 (79.4) | 3373 (77.8) | 3681 (79.8) |

| THA | 93 (5.0) | 209 (4.8) | 228 (4.9) |

Discussion

The best choice of surgical procedure for hip fracture is complex and evolving. We examined trends in relative utilization of ORIF, HA, and THA for closed femoral neck fractures during the last decade in the United States.

The limitations of our study include lack of information for clinical variables such as the degree of displacement of fractures, presence of osteoporosis, extent of osteoarthritis in the hip, prior functional status, and acetabular integrity, as these variables are not available from the databases. Because controversy regarding choice of procedure exists mainly in the management of displaced femoral neck fractures, whether the fracture was displaced plays an important role in surgical decision-making. It is unlikely there would be systematic differences in distribution of displaced versus nondisplaced femoral neck fractures with time. Also, most reports comparing THA versus HA were published after the duration of our study. However, the objective of our study was to determine trends in utilization of surgical procedures for management of femoral neck fractures and not to study which procedure had better patient outcomes. Our data source had 46% missing surgeon identifiers, making our analysis of surgeon volume exploratory. The distribution of missing surgeon identifiers, however, was similar across hospital and patient characteristics suggesting this would not substantially alter the findings.

There is debate regarding the best surgical management of displaced femoral neck fractures [5]. Numerous studies have provided evidence for better outcomes after arthroplasty (HA or THA) as compared with internal fixation [4, 7, 10, 11, 17, 20–22]. Blomfeldt et al. performed a randomized, controlled trial of 102 elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures [7]. The rate of hip complications was 4% in patients undergoing THA as compared with 42% in the internal fixation group. Revision rates were 4% in the THA group and 47% in the internal fixation group. Rogmark et al. performed a similar study comparing arthroplasty with internal fixation [20] and reported higher rates of failure and poor functional outcomes, as measured by pain and impaired walking ability, in patients undergoing internal fixation as compared with arthroplasty. Bhandari et al. reported a meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing arthroplasty and internal fixation between 1969 and 2002 [4]. Among 1933 patients, the authors reported patients undergoing arthroplasty had a relative risk of 0.23 for revision surgery as compared with those who had internal fixation. There was no difference between the two groups in pain relief after surgery, but the risk of infection was greater with arthroplasty as compared with internal fixation (relative risk = 1.81 for arthroplasty versus internal fixation).

The literature comparing THA and HA for displaced femoral neck fractures is less conclusive. In a recently reported study [14], Keating et al. reported that rates of fixation failure, hip dislocation, revision surgery, and postoperative morbidity were similar between HA and THA. However, functional outcomes and quality of life were considerably better in the THA group as compared with the HA group. Two other studies also suggest better outcomes with THA as compared with HA [8, 18]. In a recent randomized trial, Blomfeldt et al. studied elderly patients with acute displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck and concluded total hip replacement provided better function than a bipolar HA, without increasing the complication rate [6]. However, these studies have methodologic limitations such as small sample size, short duration of followup, inadequate information on randomization technique, and limited number of outcomes that were compared.

Our study shows an increase in the use of HA and a small decrease in the utilization of ORIF during the last decade. Contrary to what was expected, there also was a decrease in the utilization of THA. We observed the decrease in THA utilization across all age groups, hospital volume categories, and surgeon volume categories. The trend of minor reduction in ORIF and increase in HA with time conforms to recent studies showing better outcomes with arthroplasty as compared with internal fixation for displaced femoral neck fractures. However, a trend of decreasing THA utilization also was observed. It is likely that because there is no definitive evidence or clear clinical guidelines for use of HA versus THA in patients with femoral neck fractures, surgeons choose a technically less demanding procedure, ie, HA (particularly in less active patients). Additionally, there is evidence that better outcomes are achieved if a procedure is performed by a surgeon with high volume for the respective procedure. This has been reported for hip arthroplasties in patients without fractures [3, 13] and for shoulder arthroplasties in patients with and without fractures [9]. Therefore, outcomes may be better for a patient with a femoral neck fracture if a surgeon with low THA volume and high HA volume performs a HA. This also could be a factor in surgical decision-making.

Although evidence for better outcomes with arthroplasty as compared with internal fixation existed during the time frame of our study, most evidence comparing THA and HA was published after 2000. Given the decreasing utilization of THA in our study, it becomes essential to compare outcomes of THA versus HA for displaced femoral neck fractures. Clinical trials comparing the two procedures should be performed. Practice may lag behind the evidence. This may explain in part the decline in THAs despite preliminary evidence supporting the procedure.

In the absence of definitive trials, it is not possible to comment on whether the trend of decreasing THA utilization observed in our study is beneficial from the standpoint of patient outcomes. The role of hospital cost in the decision to perform HA versus THA is also an important variable that cannot be evaluated further from our data. It is possible, and in many cases appropriately so, that in the absence of definitive clinical guidelines hospitals/surgeons prefer HA as compared with THA owing to the cost differential. Therefore, it is essential that professional organizations develop evidence-based guidelines for the choice of procedure(s) for femoral neck fractures in different clinical situations.

Urban teaching hospitals had an increasing proportionate share of patients in the later periods of our study. Because femoral neck fracture is generally an urgent medical condition, this trend likely represents a change in the organization of trauma systems (the treatment and referral patterns of injured senior citizens) in the recent decade encouraging more patients to be transferred to academic urban hospitals by emergency services. Other possible reasons for this trend include patient preferences and referral patterns of other physicians or reductions in reimbursements with a shifting of patients to teaching hospitals. Older patients also are more likely to have multiple medical comorbidities, making their perioperative course more complex and more suitable for urban teaching hospitals.

Our study provides evidence for changing trends in the management of femoral neck fractures during the last decade. Some of these trends such as the decreasing utilization of THA raise important clinical and policy questions as described. The implications of possible variation in surgical practice by nonclinical factors such as the surgeons’ annual THA volume on patient outcomes should be investigated. Results of our study also emphasize the need for better clinical guidelines and studies on the comparison of THA and HA for displaced femoral neck fractures.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors have received funding from the Turner Fellowship (NBJ) from New England Baptist Hospital, Boston, MA and National Institutes of Health P60 AR 47782 (JNK) and National Institutes of Health K24 AR 02123 (JNK).

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp. Accessed June 1, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Quality Control Procedures. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/sasddocu/techsupp2.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2008.

- 3.Battaglia TC, Mulhall KJ, Brown TE, Saleh KJ. Increased surgical volume is associated with lower THA dislocation rates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P 3rd, Obremskey W, Koval KJ, Nork S, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH, Guyatt GH. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1673–1681. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Tornetta P 3rd, Swiontkowski MF, Berry DJ, Haidukewych G, Schemitsch EH, Hanson BP, Koval K, Dirschl D, Leece P, Keel M, Petrisor B, Heetveld M, Guyatt GH. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: an international survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2122–2130. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Blomfeldt R, Tornkvist H, Eriksson K, Soderqvist A, Ponzer S, Tidermark J. A randomised controlled trial comparing bipolar hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement for displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:160–165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Blomfeldt R, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S, Soderqvist A, Tidermark J. Comparison of internal fixation with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures: randomized, controlled trial performed at four years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1680–1688. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Healy WL, Iorio R. Total hip arthroplasty: optimal treatment for displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Jain N, Pietrobon R, Hocker S, Guller U, Shankar A, Higgins LD. The relationship between surgeon and hospital volume and outcomes for shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:496–505. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Johansson T, Jacobsson SA, Ivarsson I, Knutsson A, Wahlstrom O. Internal fixation versus total hip arthroplasty in the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: a prospective randomized study of 100 hips. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jonsson B, Sernbo I, Carlsson A, Fredin H, Johnell O. Social function after cervical hip fracture: a comparison of hook-pins and total hip replacement in 47 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:431–434. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Katz JN, Losina E, Barrett J, Phillips CB, Mahomed NN, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E, Harris WH, Poss R, Baron JA. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and outcomes of total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1622–1629. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Katz JN, Phillips CB, Baron JA, Fossel AH, Mahomed NN, Barrett J, Lingard EA, Harris WH, Poss R, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E, Wright EA, Losina E. Association of hospital and surgeon volume of total hip replacement with functional status and satisfaction three years following surgery. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:560–568. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Keating JF, Grant A, Masson M, Scott NW, Forbes JF. Randomized comparison of reduction and fixation, bipolar hemiarthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty: treatment of displaced intracapsular hip fractures in healthy older patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:249–260. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Laursen JO. Treatment of intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck in Denmark: trends in indications over the past decade. Acta Orthop Belg. 1999;65:478–484. [PubMed]

- 16.Mahomed NN, Barrett JA, Katz JN, Phillips CB, Losina E, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E, Harris WH, Poss R, Baron JA. Rates and outcomes of primary and revision total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Puolakka TJ, Laine HJ, Tarvainen T, Aho H. Thompson hemiarthroplasty is superior to Ullevaal screws in treating displaced femoral neck fractures in patients over 75 years: a prospective randomized study with two-year follow-up. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2001;90:225–228. [PubMed]

- 18.Ravikumar KJ, Marsh G. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty for displaced subcapital fractures of femur: 13 year results of a prospective randomised study. Injury. 2000;31:793–797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ray NF, Chan JK, Thamer M, Melton LJ 3rd. Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:24–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Rogmark C, Carlsson A, Johnell O, Sernbo I. A prospective randomised trial of internal fixation versus arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the neck of the femur: functional outcome for 450 patients at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:183–188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Soreide O, Molster A, Raugstad TS. Internal fixation versus primary prosthetic replacement in acute femoral neck fractures: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Br J Surg. 1979;66:56–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Soderqvist A, Tornkvist H. Internal fixation compared with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly: a randomised, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:380–388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Whalen D, Houchens R, Elixhauser A. Final 2000 NIS Comparison Report. HCUP Methods Series Report #2003-1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/2000NISComparisonReportFinal.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2008.