Abstract

Objective To evaluate benefits for postnatal women of two psychologically informed interventions by health visitors.

Design Prospective cluster trial randomised by general practice, with 18 month follow-up.

Setting 101 general practices in Trent, England.

Participants 2749 women allocated to intervention, 1335 to control.

Intervention Health visitors (n=89 63 clusters) were trained to identify depressive symptoms at six to eight weeks postnatally using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) and clinical assessment and also trained in providing psychologically informed sessions based on cognitive behavioural or person centred principles for an hour a week for eight weeks. Health visitors in the control group (n=49 38 clusters) provided usual care.

Main outcome measures Score ≥12 on the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale at six months. Secondary outcomes were mean Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measure (CORE-OM), state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI), SF-12, and parenting stress index short form (PSI-SF) scores at six, 12, 18 months.

Results 4084 eligible women consented and 595 women had a six week EPDS score ≥12. Of these, 418 had EPDS scores available at six weeks and six months. At six months, 34% women (93/271) in the intervention group and 46% (67/147) in the control group had an EPDS score ≥12. The odds ratio for score ≥12 at six months was 0.62 (95% confidence interval 0.40 to 0.97, P=0.036) for women in the intervention group compared with women in the control group. After adjustment for covariates, the odds ratio was 0.60 (0.38 to 0.95, P=0.028). At six months, 12.4% (234/1880) of all women in the intervention group and 16.7% (166/995) of all women in the control group had scores ≥12 (0.67, 0.51 to 0.87, P=0.003). Benefit for women in the intervention group with a six week EPDS score ≥12 and for all women was maintained at 12 months postnatally. There was no differential benefit for either psychological approach over the other.

Conclusion Training health visitors to assess women, identify symptoms of postnatal depression, and deliver psychologically informed sessions was clinically effective at six and 12 months postnatally compared with usual care.

Trial registration ISRCTN92195776.

Introduction

Postnatal depression is a global problem and an important public health issue. About 13% of women experience depression during the first postnatal year,1 yet there are problems in recognition because its clinical assessment is complex. There can be serious consequences for the mother, her child,2 and family and a risk of suicide (the leading cause of maternal death in England and Wales) and infanticide in some severely depressed mothers.3 Fathers are also more likely to be depressed if their partner is depressed,4 and the children of fathers who experience depression in the postnatal period are at increased risk of behaviour problems.5

In primary care, psychological interventions are as clinically effective in the management of depression as routine care from a general practitioner or antidepressants in the short term and might be cost effective.6 7 8 9 10 There are problems in treating postnatal women with antidepressants11 and psychological therapies provide a practical alternative12 and are preferred by women.13 In the United Kingdom the role of health visitors in managing postnatal depression has been promoted.14

Cochrane and other reviews covering studies worldwide have examined interventions for postnatal depression.15 16 They found insufficient good evidence to recommend treatment, mainly because of inadequacies in design or reporting of random allocation method, sample size, follow-up, or failure to use intention to treat analysis. Psychosocial and psychological interventions might be an effective treatment option, but the long term effectiveness remains unclear.16

In this pragmatic trial we examined outcomes for postnatal women of special training for health visitors compared with usual care. We chose a cluster allocation by general practice to minimise contamination between intervention and control group. We tested the hypotheses that there would be no differences between the groups in outcome for mother, infant, or family nor between the groups randomised to the two different psychological approaches.

Methods

Setting and participants

The pragmatic cluster trial took place from April 2003 to March 2006 in 101 general practices (clusters) in 29 primary care trusts in the former Trent Regional Health Authority, comprising a blend of urban and rural areas, with a population of about 5.2 million people. Clusters were eligible if they were based in the Trent region. Health visitors recruited eligible women antenatally if they were registered with participating practices, were aged 18 or more, were able to give informed consent, and had no severe mental health problems. In 101 clusters there were 7649 eligible women, and 4084 consented to take part.

Health visitor training

Health visitors in the intervention group were trained to identify depressive symptoms using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS)17 and to use clinical assessment skills to assess a mother’s mood including suicidal thoughts. The EPDS is a self report measure with a score ranging from 0 to 30 (the highest symptom level). It is widely used in research and clinical practice but on its own is inadequate for confirming depression without a clinical interview. These health visitors were also trained to deliver psychologically informed sessions based on distinct psychological theories, either cognitive behavioural principles18 or on person centred principles.19 We then compared these two approaches.

Baseline measurement and identification of women with six week score ≥12

Women were sent a postal questionnaire at six weeks postnatally to collect demographic details, measure depressive symptoms using the EPDS, and measure social support and stressful life events using the measure of social relationships20 and list of threatening experiences,21 and previous depression.22

Administration of the questionnaire coincided with an existing health visitor contact. We used the recommended pragmatic EPDS threshold score of 12 to identify women with symptoms of depression.23 24 In the first validation study, this score correctly identified all women with major depression and most with minor depression.17 The sensitivity for identifying depressed women (true positives) was 86% and the specificity for identifying true negatives was 78%. A cut off of 9 or 10 correctly identified all women with definite minor depression but the original researchers considered that there would be an untenable workload for health visitors if health visitors used this lower threshold.23 As some women could simply be unhappy when they completed the six week EPDS, women with a raised score completed a repeat EPDS after two weeks to identify those who needed further support.24

We used the recommended score17 to identify women more likely to benefit from psychologically informed sessions. The main comparison was between women in the two groups with an EPDS score ≥12 at six weeks.

We also followed up all consented women as some who scored <12 at six weeks might have been depressed at that time and others would have developed depression over the following months. All women whose infants were 6, 12, and 18 months old within the trial follow-up phase were sent a postal follow-up questionnaire.

Intervention group

In clusters in the intervention group the psychologically informed approach comprised a package of health visitor training, combining three main elements of assessing women, identifying depressive symptoms, and delivering either a cognitive behavioural18 or a person centred approach.19 A training reference group of experienced academically based trainers in psychological therapy, who represented both the cognitive behavioural and person centred approaches, maximised the rigour, effectiveness, and comparability of the two training programmes. This was to ensure that the trial would be considered by advocates of each approach to have been a credible and fair test of that approach. The manualised health visitor training ensured that unintentional bias supporting either of the two interventions was minimised and prepared the health visitors to provide an appropriate, pragmatic, distinctive, derivative approach, delivering critical elements from cognitive behavioural therapy or person centred therapy, not psychotherapy.

The common areas for training in both approaches enabled health visitors to acquire further generic skills in developing helpful relationships such as positive regard and empathy. The cognitive behavioural training emphasised the identification of unhelpful patterns of behaviours, perceptions, or thoughts in a woman’s life, and that these are common and normal, to help the woman to change these herself.18 The person centred training used the three principles of the actualising tendency, a non-directive attitude, and the necessary and sufficient conditions of change.19 Person centred counselling has previously been referred to as non-directive counselling.25 See bmj.com for further details on the training of the health visitors.

As usual in the application of psychologically informed approaches in the NHS, the health visitors had access to clinical supervision with the trainers by telephone. The health visitors were asked to attend monthly reflective practice sessions to ensure they carried out the sessions according to their training.

Women eligible for psychologically informed sessions

In the intervention group the health visitors re-administered the EPDS face to face at eight weeks postnatally to all women with a six week EPDS score ≥12. Those who still had a score ≥12 were offered either cognitive behavioural or person centred sessions according to the cluster randomisation.

The health visitor delivered weekly one hour sessions in the woman’s home for up to eight weeks, focusing on the woman’s needs, starting around eight weeks postnatally.

Usual care

In the UK, general practitioners, midwives, and hospital obstetricians meet women early in pregnancy to plan care. Care is then given by a midwife, shared between the midwife and possibly a general practitioner, or otherwise. Consultant led care is based on clinical need. UK health visitors have routine contact with women at a new birth visit and at well baby clinics.

Before random allocation, 47% of all participating health visitors had used an EPDS assessment at six weeks postnatally, according to primary care trust policy, and would typically refer women to a general practitioner but not offer psychologically informed sessions. After randomisation, control health visitors in 38 clusters continued to represent this variability so women in the control group continued to receive the range of usual postnatal care as provided by these health visitors. All health visitors continued to fulfil other aspects of their role.

Outcomes

We measured outcomes using a postal questionnaire at six, 12, and 18 months postnatally.

Primary outcome—The patient centred primary outcome was the proportion of women with a six week EPDS ≥12, who had a six month EPDS score ≥12.

Secondary outcomes—Secondary outcomes included the mean EPDS score at six and 12 months postnatally. The other secondary outcomes had all been used with perinatal women and had good psychometric properties.15 To capture the broader impact of the intervention we measured women’s general health using the SF-12 mental component summary (SF-MCS) and physical component summary (SF-PCS).26 We used the clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measure (CORE-OM)27 as a measure of global distress. We also measured symptoms of postnatal anxiety using the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI)28 because anxiety disorders are as common as depression after delivery.29 Women completed the parenting stress index short form (PSI-SF)30 as a measure of adjustment to new parenthood.

Recruitment and randomisation

We systematically approached a range of networks to facilitate the recruitment of clusters. Health visitors worked with the general practitioners, were usually based in the same premises, and held a caseload of families registered with the practice. To avoid selection bias in the clusters, health visitors and a general practitioner in each practice signed a consent form before the random allocation. The health visitors aimed to recruit all eligible individual women on their caseload consecutively to avoid bias in the selection of women.

Sequence generation and random assignment

An independent statistician generated the allocation sequence using a computer randomisation programme (RANDOM, Southampton University). To minimise imbalance across groups, the clusters were stratified by the number of expected births per cluster per year into three groups (<70, 70-100, >100). Clusters were allocated to either cognitive behavioural or person centred approach (intervention) or the control group in a ratio of 1:1:1. The sequence was concealed to clusters. The principal investigator (CJM) enrolled the general practitioners and health visitors and informed them of their allocation. We could not blind participants or health visitors to group assignment.

Sample size calculation

To calculate the sample size we assumed an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.00631 and an average of six women per cluster with a six week score ≥12. Eighty seven clusters or 520 women with a six week score ≥12 (350 intervention, 170 control) would yield 90% power at the 5% two sided level of significance to detect a 15% absolute difference (50% v 35%) in the proportions of women in each group with a six month score ≥12. We assumed a 20% loss to follow-up at six months, requiring 649 women in total and a recruitment phase of 15 months. Within the intervention group we also had 80% power to detect a 15% significant difference in the proportions of women with a six month score ≥12 (43% v 28%) between the two intervention groups.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were by intention to treat, analysed as randomised, irrespective of receipt of psychologically informed sessions, with P<0.05 regarded as significant. The primary analysis compared scores at six months for women with a six week EPDS score ≥12 in all intervention clusters with those in the control group.

We used a marginal generalised linear model with coefficients estimated using generalised estimating equations32 with robust standard errors and an exchangeable auto correlation matrix in Stata v8 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) to analyse the outcomes and adjust for the potential clustering of the data. We have shown estimates of the group coefficients from these regression models with their associated 95% confidence intervals. In all the analyses we first fitted a simple model and then one to adjust for individual level covariates (living alone, history of postnatal depression, and stressful life events, as the strongest predictors of postnatal depression)22 and six week EPDS score. For secondary outcomes we compared mean values at six, 12, and 18 months using similar models. We included in the statistical analysis women with EPDS scores at both six weeks and six months and did not impute missing data.

Results

Cluster characteristics

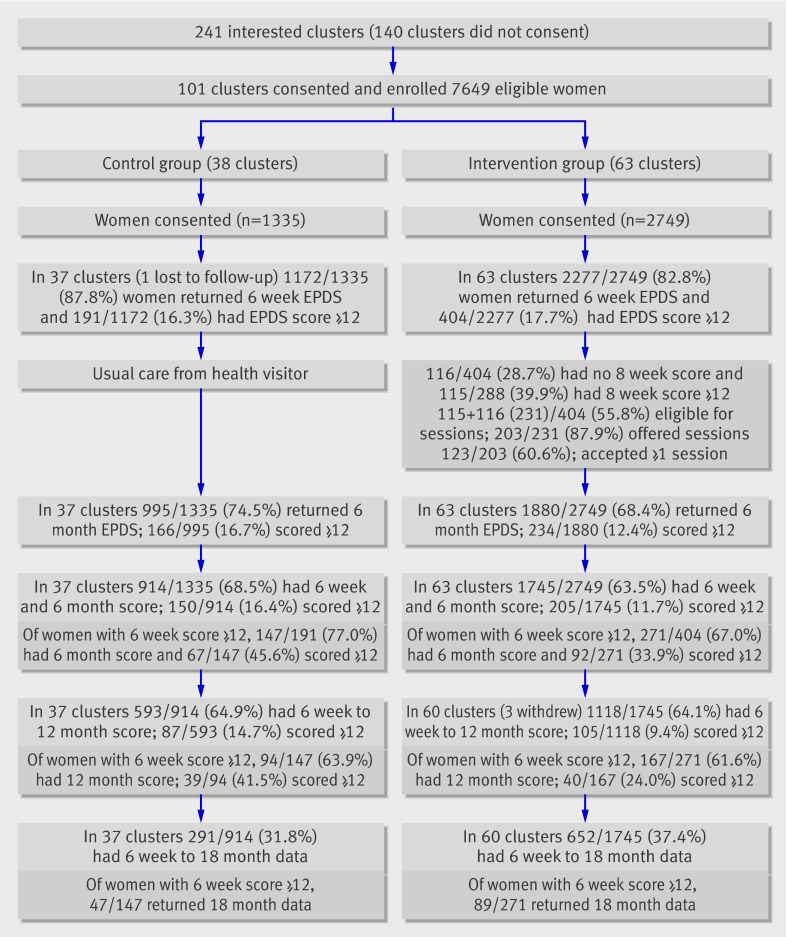

Figure 1 shows the flow of clusters and participants through the trial. Among 241 interested practices, 101 consented to take part. These recruited practices were in areas representative of Trent and England as a whole according to the index of multiple deprivation.33 The 101 clusters yielded 7649 eligible women of whom 4084 (53%) with a live baby consented to take part.

Fig 1 Trial profile of clusters, all women and women with six week EPDS score ≥12 in control and intervention groups. Note: 597 women were not sent 12 month questionnaire as their baby was <12 months, and 1879 women were not sent 18 month questionnaire as their baby was not 18 months when follow-up interval ended

Six week response and identification of women with six week EPDS score ≥12

Of all the women in 101 clusters, 85% (3449/4084) completed a six week questionnaire: 16% (191/1172) in the control group and 18% (404/2277) in the intervention group scored ≥12 on the EPDS.

Characteristics of women in the comparison groups

Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics of women with a six week EPDS score ≥12 (n=418) and all women (n=2659) who returned questionnaires at six weeks and six months, indicating that the randomisation resulted in well balanced groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women with score ≥12 on Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) at six weeks postnatally and all consented women who returned questionnaire at six weeks and six months, for intervention group (specially trained health visitors) versus control group (usual care). Figures are means (SD) or numbers (percentages) of women

| Women with six week EPDS score ≥12 (n=418) | All women (n=2659) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | All | Control | Intervention | All | ||

| Age (years): | |||||||

| No of women | 147 | 271 | 418 | 913 | 1745 | 2658 | |

| Mean (SD) | 30.6 (5.5) | 31.0 (5.4) | 30.9 (5.4) | 32.0 (5.1) | 31.3 (5.0) | 31.5 (5.1) | |

| Age (years) at birth of first child: | |||||||

| No of women | 145 | 265 | 410 | 889 | 1714 | 2603 | |

| Mean (SD) | 27.5 (6.0) | 27.4 (5.8) | 27.4 (5.8) | 29.0 (5.3) | 28.0 (5.3) | 28.4 (5.3) | |

| No of other children: | |||||||

| No of women | 147 | 271 | 418 | 914 | 1745 | 2659 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.9) | |

| EPDS score at six weeks: | |||||||

| No of women | 147 | 271 | 418 | 914 | 1745 | 2659 | |

| Mean (SD) | 15.4 (3.2) | 15.1 (2.9) | 15.2 (3.0) | 6.8 (5.0) | 6.6 (4.8) | 6.7 (4.8) | |

| CORE-OM score at six weeks: | |||||||

| No of women | 146 | 269 | 415 | 906 | 1735 | 2641 | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.40 (0.50) | 1.35 (0.49) | 1.37 (0.49) | 0.55 (0.51) | 0.51 (0.49) | 0.52 (0.50) | |

| SF-12 MCS score at six weeks: | |||||||

| No of women | 143 | 265 | 408 | 888 | 1719 | 2607 | |

| Mean (SD) | 29.4 (9.2) | 29.1 (8.0) | 29.2 (8.4) | 42.7 (9.5) | 42.9 (9.3) | 42.9 (9.4) | |

| SF-12 PCS score at six weeks: | |||||||

| No of women | 143 | 265 | 408 | 888 | 1719 | 2607 | |

| Mean (SD) | 48.5 (10.9) | 50.1 (9.4) | 49.6 (10.0) | 50.5 (8.7) | 51.4 (8.0) | 51.1 (8.3) | |

| Twin births | 2/147 (1.4) | 3/270 (1.1) | 5/417 (1.2) | 5/833 (0.6) | 19/1727 (1.1) | 24/2560 (0.9) | |

| Living alone with no adults | 7/146 (4.8) | 19/269 (7.1) | 26/415 (6.3) | 31/912 (3.4) | 58/1706 (3.3) | 89/2618(3.4) | |

| History of major life events | 73/145 (50.3) | 152/269 (56.5) | 225/419 (54.3) | 368/906 (40.6) | 715/1735 (41.2) | 1083/2641 (41.0) | |

| White ethnicity | 133/147 (90.5) | 257/271 (94.8) | 390/418 (93.3) | 871/914 (95.3) | 1686/1744 (96.6) | 2557/2658 (96.2) | |

| English first language | 136/147 (92.5) | 266/271 (98.2) | 402/418 (96.2) | 877/914 (96.0) | 1699/1744 (97.4) | 2576/2658 (96.9) | |

CORE-OM=clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measure; SF-12 MCS=short form 12 mental component summary; SF-12 PCS=short form 12 physical component summary. Better health represented by lower EPDS and CORE-OM score and higher SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS score.

Six month follow-up and analysis for women with six week EPDS score ≥12

Seventy per cent (418/595) of women with a six week EPDS score ≥12 from 86 clusters had a six week and a six month score available for analysis; 77% (147/191) in the control group v 67% (271/404) in the intervention group (fig 1). For the primary outcome, 46% women (67/147) in the control group and 34% (93/271) in the intervention group scored ≥12 on the six month EPDS (table 2). The difference of 11.7% (95% confidence interval 0.4% to 22.9%) was significant (P=0.039). This means that we would need to treat nine women who had a six week EPDS score ≥12 for one additional woman to have an EPDS score <12 at six months.

Table 2.

Primary outcome: numbers (percentages) of women with score ≥12 on Edinburgh postnatal depression scale at six months among 418* women with score ≥12 at six weeks, all women (n=2659*), and 2241 women with score <12 at six weeks

| Control | Intervention | % Difference (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | ||||

| Score ≥12 at six weeks | 67/147 (45.6) | 92/271 (33.9) | 11.7 (0.4 to 22.9) | 0.62 (0.40 to 0.97), P=0.036 | 0.60 (0.38 to 0.95), P=0.028 |

| All women | 150/914 (16.4) | 205/1745 (11.7) | 4.7 (0.7 to 8.6) | 0.67 (0.51 to 0.87), P=0.003 | 0.67 (0.52 to 0.86), P=0.002 |

| Score <12 at six weeks | 83/767 (10.8) | 113/1474 (7.7) | 3.1 (0.4 to 5.9) | 0.68 (0.51 to 0.92), P=0.016 | — |

*For adjusted odds ratio, n=409 for women with score ≥12 at six weeks and 2624 for all women.

†Adjusted for score at six weeks, living alone, history of postnatal depression, any life events.

After adjustment for living alone, history of postnatal depression, stressful life events, and six week EPDS score the odds ratio (0.60, 0.38 to 0.95, P=0.028) further indicated that women in the intervention group with a six week score ≥12 were 40% less likely to have a six month score ≥12 than women in the control group.

For women with a six week score ≥12, the mean EPDS score at six months was 11.3 (SD 5.8) in the control group and 9.2 (SD 5.4) in the intervention group (table 3). The mean difference of −2.1 (−3.4 to −0.8, P=0.002) remained significant after we adjusted for variables at six weeks (P=0.001). Table 3 also shows the differences in the mean scores for the secondary outcomes in favour of the intervention group women with a six week EPDS score ≥12.

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes at six months for women with score ≥12 on Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) at six weeks and all women, for control group versus intervention group

| Control | Intervention | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of women | Mean (SD) | No of women | Mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI) | P value | Difference (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Women with score ≥12 at six weeks (n=418): | |||||||||||

| EPDS | 147 | 11.3 (5.8) | 271 | 9.2 (5.4) | −2.1 (−3.4 to −0.8) | 0.002 | −2.1 (−3.3 to −0.9) | 0.001 | |||

| CORE-OM | 146 | 1.05 (0.69) | 269 | 0.82 (0.62) | −0.23 (−0.39 to −0.07) | 0.006 | −0.22 (−0.36 to −0.09) | 0.001 | |||

| STATE anxiety | 136 | 45.5 (12.5) | 254 | 41.7 (11.8) | −3.8 (−6.6 to 1.0) | 0.008 | −3.9 (−6.1 to −1.4) | 0.003 | |||

| SF-12 MCS | 142 | 37.8 (11.8) | 263 | 42.3 (10.8) | 4.7 (1.8 to 7.6) | 0.001 | 5.2 (2.5 to 7.8) | 0.001 | |||

| SF-12 PCS | 142 | 54.3 (9.0) | 263 | 53.0 (7.6) | −1.4 (−3.5 to 0.7) | 0.204 | −1.7 (−3.6 to 0.1) | 0.069 | |||

| PSI-SF total stress | 106 | 139.6 (20.4) | 211 | 148.9 (17.0) | 9.2 (4.8 to 13.7) | 0.001 | 9.3 (5.2 to 13.4) | 0.001 | |||

| All women (n=2659): | |||||||||||

| EPDS | 914 | 6.4 (5.2) | 1745 | 5.5 (4.7) | −1.0 (−1.5 to −0.4) | 0.001 | −0.8 (−1.2 to −0.4) | 0.001 | |||

| CORE-OM | 906 | 0.53 (0.53) | 1736 | 0.45 (0.46) | −0.09 (−0.15 to −0.04) | 0.001 | −0.07 (−0.11 to −0.03) | 0.001 | |||

| STATE anxiety | 858 | 34.3 (11.7) | 1634 | 33.2 (10.9) | −1.3 (−2.7 to −0.1) | 0.042 | −1.3 (−2.5 to −0.1) | 0.033 | |||

| SF-12 MCS | 885 | 47.6 (10.5) | 1694 | 48.9 (9.5) | 1.5 (0.3 to 2.6) | 0.010 | 1.4 (0.5 to 2.3) | 0.003 | |||

| SF-12 PCS | 885 | 54.5 (6.8) | 1694 | 54.7 (6.1) | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.7) | 0.469 | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.5) | 0.871 | |||

| PSI-SF total stress | 698 | 155.9 (16.9) | 1310 | 157.9 (15.3) | 2.1 (0.3 to 3.9) | 0.021 | 2.3 (0.6 to 3.9) | 0.007 | |||

CORE-OM=clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measure; SF-12 MCS=short form 12 mental component summary; SF-12 PCS=short form 12 physical component summary; PSI-SF=parenting stress index short form. Better health represented by lower score in EPDS, CORE-OM, and STATE anxiety; higher score in others

*Adjusted for six week score, living alone, history of postnatal depression, any life events.

Six month follow-up and analysis for all women as randomised

Of all the women who returned a six week questionnaire, 77% (2659/3449) also returned a six month questionnaire (fig 1): 78% (914/1172) in the control group and 77% (1745/2277) in the intervention group.

At the six month follow-up 16% (150/914) of all women in the control group and 12% (205/1745) of all women in the intervention group had a six week score ≥12, an absolute difference of 4.7% (0.7% to 8.6%, P=0.003). The difference was still significant (P=0.002) after we adjusted for living alone, history of postnatal depression, stressful life events, and six week EPDS score (table 2). The mean score was 6.4 (SD 5.2) in the control group and 5.5 (SD 4.7) in the intervention group (P<0.001) (table 3). Table 3 also shows the secondary outcome mean scores for all women favouring the intervention group women.

Intracluster correlation coefficient

The observed intracluster correlation coefficient for the primary outcome at six months was 0.037 (0.000 to 0.114) for the 418 women with a six week score ≥12 in 86 clusters and 0.009 (0.000 to 0.022) for all 2659 women in 100 clusters.

Comparison of the cognitive behavioural approach and person centred approach

Examination of the two intervention groups separately showed that 33% (46/140) of women with a six week score ≥12 in the cognitive behavioural group and 35% (46/131) in the person centred group had a six month score ≥12 (P=0.74) (table 4). The mean six month score was 9.2 (SD 5.3) for women in the cognitive behavioural group and 9.2 (SD 5.5) for women in the person centred group (P=0.99).

Table 4.

Primary outcome: numbers (percentages) of women with score ≥12 on Edinburgh postnatal depression scale at six months among 418* women with score ≥12 at six weeks and all women (n=2659*) according to therapeutic approach: cognitive behavioural (CBA) or person centred (PCA)

| CBA | PCA | Difference % (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

| Score ≥12 at six weeks | 46/140 (32.9) | 46/131 (35.1) | 2.2 (−10.1 to 14.2) | 1.09 (0.64 to 1.88), P=0.74 | 1.00 (0.57 to 1.77), P=0.99 |

| All women | 98/848 (11.6) | 107/897 (11.9) | 0.3 (−2.6 to 3.4) | 1.04 (0.78 to 1.39), P=0.80 | 1.09 (0.81 to 1.46), P=0.59 |

*For adjusted odds ratio, n=265 for women with score ≥12 at six weeks and 1726 for all women.

For all women in the intervention group, 12% (98/848) in the cognitive behavioural group and 12% (107/897) in the person centred group had a six month score ≥12 (P=0.80). The mean six month score was 5.5 (SD 4.7) for all women in each of the groups (P=0.94).

Secondary outcomes at 12 and 18 months

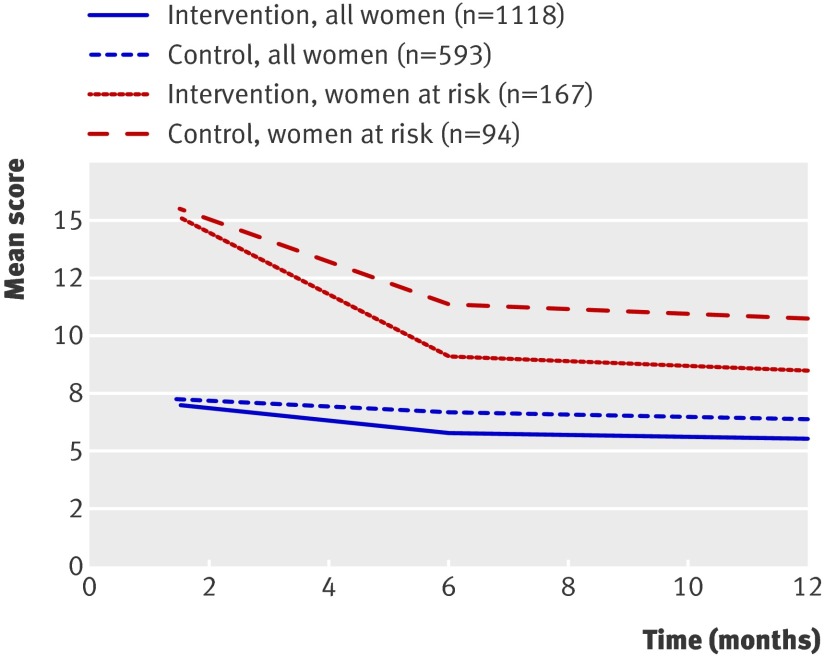

Figure 2 shows how the mean score changed over time from six weeks to 12 months for women with a six week score ≥12 and all women by group. Table 5 shows that the differences in the mean EPDS scores at six months and secondary outcome scores were sustained at 12 months for the women with a six week score ≥12 and for all women. Table 6 shows that in some measures, differences in secondary outcomes were maintained at the 18 month follow-up for women with a six week score ≥12 and for all women.

Fig 2 Mean EPDS scores over time by intervention and control group for women at risk (score ≥12 on EPDS at six weeks) and for all women

Table 5.

Secondary outcomes at 12 months for women with score ≥12 on Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) at six weeks and all women, for control group versus intervention group

| Control | Intervention | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of women | Mean (SD) | No of women | Mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI) | P value | Difference (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Score ≥12 at six weeks: | |||||||||||

| EPDS | 94 | 10.6 (6.2) | 167 | 8.1 (5.6) | −2.5 (−4.3 to −0.9) | 0.003 | −2.4 (−4.1 to −0.7) | 0.005 | |||

| CORE-OM | 94 | 1.00 (0.68) | 167 | 0.75 (0.62) | −0.26 (−0.44 to −0.08) | 0.005 | −0.21 (−0.38 to −0.04) | 0.015 | |||

| STATE anxiety | 93 | 45.0 (13.2) | 162 | 40.7 (12.6) | −4.3 (−8.1 to −0.7) | 0.019 | −4.2 (−7.8 to −0.5) | 0.025 | |||

| SF-12 MCS | 92 | 40.8 (10.9) | 161 | 44.9 (10.9) | 4.1 (1.3 to 6.9) | 0.004 | 3.8 (1.0 to 6.6) | 0.008 | |||

| SF-12 PCS | 92 | 54.1 (7.5) | 161 | 53.9 (7.0) | −0.2 (−2.0 to 1.7) | 0.857 | −0.4 (−2.0 to 1.3) | 0.650 | |||

| PSI-SF total stress | 90 | 140.7 (21.4) | 156 | 148.7 (19.2) | 8.0 (3.1 to 13.0) | 0.001 | 8.1 (3.6 to 12.6) | 0.001 | |||

| All women: | |||||||||||

| EPDS | 593 | 5.9 (5.2) | 1118 | 5.0 (4.6) | −0.9 (−1.5 to −0.3) | 0.002 | −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.2) | 0.003 | |||

| CORE-OM | 593 | 0.51 (0.53) | 1120 | 0.42 (0.46) | −0.09 (−0.16 to −0.04) | 0.001 | −0.07 (−0.12 to −0.03) | 0.001 | |||

| STATE anxiety | 580 | 33.7 (11.7) | 1097 | 32.4 (10.7) | −1.5 (−2.7 to −0.2) | 0.019 | −1.4 (−2.5 to −0.2) | 0.020 | |||

| SF-12 MCS | 579 | 48.7 (9.8) | 1099 | 49.9 (9.2) | 1.1 (0.2 to 2.0) | 0.013 | 0.9 (0.1 to 1.6) | 0.022 | |||

| SF-12 PCS | 579 | 55.0 (6.4) | 1099 | 55.0 (6.0) | 0.0 (−0.6 to 0.8) | 0.834 | −0.2 (−0.8 to 0.5) | 0.590 | |||

| PSI-SF total stress | 558 | 155.6 (17.1) | 1055 | 157.0 (15.6) | 1.43 (−0.4 to 3.0) | 0.137 | 1.1 (−0.3 to 2.7) | 0.123 | |||

CORE-OM=clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measure; SF-12 MCS=short form 12 mental component summary; SF-12 PCS=short form 12 physical component summary; PSI-SF=parenting stress index short form. Better health represented by lower score in EPDS, CORE-OM, and STATE anxiety; higher score in others.

*Adjusted for six week score, living alone, history of postnatal depression, any life events.

Table 6.

Outcomes at 18 months for women with score ≥12 at six weeks on Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) and all women, for control group versus intervention group

| Control | Intervention | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of women | Mean (SD) | No of women | Mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI) | P value | Difference (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Score ≥12 at six weeks: | |||||||||||

| CORE-OM | 47 | 0.95 (0.77) | 88 | 0.78 (0.67) | −0.17 (−0.45 to 0.11) | 0.228 | −0.08 (−0.27 to 0.10) | 0.374 | |||

| STATE anxiety | 46 | 42.7 (14.5) | 85 | 40.8 (14.5) | −1.9 (−6.9 to 3.5) | 0.521 | −1.3 (−5.8 to 3.2) | 0.578 | |||

| SF-12 MCS | 46 | 40.2 (7.1) | 86 | 39.5 (5.4) | −0.7 (−2.9 to 1.3) | 0.463 | −0.7 (−2.7 to 1.3) | 0.509 | |||

| SF-12 PCS | 46 | 52.1 (12.9) | 86 | 56.0 (8.6) | 3.9 (1.1 to 7.1) | 0.007 | 2.9 (−0.1 to 6.0) | 0.062 | |||

| PSI-SF total stress | 46 | 138.1 (23.2) | 82 | 147.2 (21.2) | 9.1 (1.1 to 17.4) | 0.026 | 9.0 (1.6 to 16.4) | 0.017 | |||

| All women: | |||||||||||

| CORE-OM | 291 | 0.54 (0.55) | 650 | 0.43 (0.49) | −0.11 (−0.18 to −0.03) | 0.005 | −0.07 (−0.13 to −0.02) | 0.011 | |||

| STATE anxiety | 281 | 34.0 (11.8) | 631 | 32.6 (10.8) | −1.5 (−3.4 to 0.4) | 0.116 | −1.4 (−3.1 to 0.3) | 0.105 | |||

| SF-12 MCS | 286 | 40.1 (5.7) | 634 | 40.0 (4.8) | −0.0 (−0.6 to 0.5) | 0.875 | −0.0 (−0.5 to 0.4) | 0.846 | |||

| SF-12 PCS | 286 | 57.2 (10.1) | 634 | 59.1 (7.2) | 1.8 (0.6 to 3.1) | 0.005 | 1.4 (0.2 to 2.6) | 0.022 | |||

| PSI-SF total stress | 276 | 153.0 (19.4) | 628 | 156.3 (16.5) | 3.3 (0.8 to 5.8) | 0.009 | 3.2 (0.9 to 5.6) | 0.007 | |||

CORE-OM=clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measure; SF-12 MCS=short form 12 mental component summary; SF-12 PCS=short form 12 physical component summary; PSI-SF=parenting stress index short form. Better health represented by lower score in CORE-OM and STATE anxiety; higher score in others.

*Adjusted for six week EPDS score, living alone, history of postnatal depression, any life events.

Discussion

This pragmatic cluster trial provides new evidence34 of the effectiveness of a package of training for health visitors to identify symptoms of depression postnatally and to provide psychologically informed sessions.35 In the intervention group we found a reduction in depressive symptoms in postnatal women as measured by the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale and by secondary outcomes at six and 12 months postnatally among women with a six week EPDS score ≥12 as well as among all women as randomised. It is important to note that the comparison was between the intervention group and a usual care control group, rather than a no treatment control group.

There was also some evidence of a benefit in favour of the intervention group for some of the secondary outcomes at the 18 month follow-up. As fewer women were sent a follow-up questionnaire at 18 months, however, more uncertainty surrounds these outcomes.

Strengths of the study

The trial has good internal and external validity and, with more than twice as many participants as the previous largest study,36 provides more evidence than before of the benefit of psychologically informed approaches for women with postnatal depression.16 We followed postnatal women to 18 months, whereas the final outcome in most previous studies of postnatal depression was measured at one to three months postnatally,12 and also incorporated an economic evaluation.

We achieved the required number of clusters. The characteristics of the practices collaborating in the study were representative of those in England, indicating good external validity. The attributes of health visitors are also probably generalisable. We estimated that 50% of all eligible women might consent to take part and 53% consented, even though recruitment relied on another agency (the health visitors) rather than researchers. The similar characteristics of the women with a six week EPDS score ≥12 in the intervention and control clusters indicate that the stratified randomisation process was effective, imparting good internal validity. We believe the women’s characteristics were similar to those for women in England, and women in this trial were representative of women experiencing postnatal depression in real world primary care and typical of women who use the service.

Of all the women, 17.3% (595/3449) scored ≥12 on the six week EPDS, and the mean score for these women was 15.2. It was inevitable that not all women with a six week score ≥12 would be eligible for the psychologically informed sessions as the study was designed to filter out women with transient depressive symptoms by the re-administration of the EPDS at eight weeks postnatally.

Of the intervention group women with a six week EPDS score ≥12 who completed the EPDS at eight weeks, 60% (173/288) scored <12 and therefore did not fulfil the criterion for the psychologically informed sessions. Not all women completed an eight week EPDS according to the protocol, principally because the woman declined or could not be contacted. Some women were not assessed at eight weeks because the health visitor was absent (sick or on holiday). In reality health visitors might not always repeat the EPDS for a range of practical reasons. Also, as in the real world, the “clinical judgment” of health visitors dominated the decision to offer psychologically informed sessions, without the benefit of an eight week score.37

We would need to treat nine women with a six week EPDS score ≥12 for one additional woman to have an EPDS score <12 at six months. This number is derived from the absolute risk and is moderately good in this context. A small number needed to treat (NNT)—that is, approaching one—indicates that a favourable outcome occurs in nearly every person who receives the treatment and in few patients in a comparison group. Though a number needed to treat approaching one is possible, they are almost never found in practice, but small numbers needed to treat do occur in some therapeutic trials.38

We are aware of no other trials of drug or psychologically informed interventions in a homogeneous group of women that report proportions of women with six month scores ≥12. Two trials reported EPDS scores at 12 and 13 weeks,12 39 and a third study (that allocated to group using coded slips of paper drawn from a bag) reported Beck depression inventory and Beck anxiety inventory at 12 weeks after the intervention.40

Limitations and potential sources of bias

One limitation in the interpretation of the results arises from the differential loss to follow-up at six months among the women with a six week score ≥12: 23% of women (44/191) in the control group and 33% (133/404) in the intervention group did not complete the six month EPDS. In the control group there was no difference between the mean EPDS scores at six weeks in those women who did (15.4) and did not (15.1) complete a six month EPDS. The corresponding scores in the intervention group were 15.1 and 16.2. The potential impact of this on our results is unclear, although we did adjust the six month scores for the baseline six week score.

Another limitation is our use of the threshold score ≥12 to assess the level of depressive symptoms at six months postnatally. As the sensitivity of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale at this threshold is 86%, the presence of these self reported symptoms might not necessarily have met the psychiatric criteria for a primary diagnosis of depression. Conversely, some women with a score below the threshold of 12 might have had symptoms of depression not included in the EPDS (specificity 78%) or might have chosen to conceal their symptoms.41

The mechanism of action is unclear because of the improvement in the intervention group, despite the unexpectedly low uptake of the psychologically informed sessions. In the intervention group 404 women had a six week score ≥12, but 173 were not eligible for sessions as they had an eight week score <12. However, 49% (199/404) of women were offered sessions and 60% (120/199) accepted. Of the 404 women, 271 (67%) returned a six month questionnaire. Of these, 46% (124/271) were offered sessions and 62% (77/124) accepted. The median number of sessions attended was four (interquartile range two to seven). The women might have had practical reasons, such as lack of time, for not accepting the sessions.42

We found a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in all the women in the intervention clusters, including the 2241 with a six week score <12, of whom 11% (83/767) in the control group and 8% (113/1474) in the intervention group had a six month score <12. These results suggest that non-specific effects of the health visitor intervention were operating to generate the improvement extending beyond the women with a six week score ≥12. As this was a pragmatic rather than explanatory trial, we can only speculate about the cause of the positive outcomes.

Because the health visitor intervention combined different training components, it is difficult to disentangle which elements might have been more effective. Importantly, the health visitors used their skills acquired during training to assess women, identify those with postnatal depressive symptoms, and offer support and deliver specific psychologically informed sessions. Health visitors have a unique opportunity to engage with all postnatal women on their caseload. The unexpected effect might have arisen because the training equipped the health visitors with the confidence in their skills, which they were motivated to generalise beyond the original protocol specification for the women with a six week score ≥12.43 That is, as a result of their training, health visitors in the intervention group might have extended their enhanced relationship skills, such as warmth and empathy, thereby improving engagement with all women on their caseload antenatally and postnatally.

The intervention comprised other components, which might also have affected the emotional status of the new mothers. These were antenatal contact, the early development of the mother-health visitor relationship, and emphasis on focusing on the woman rather than solely the baby.

For those women who were offered but declined the psychologically informed sessions, the knowledge that the health visitor was aware of their emotional state and the offer in itself might have been perceived as support. Having someone in whom to confide has been identified as one of the main functional elements of social support for coping with stressful situations, and there is evidence of an association between absence of such a close relationship and symptoms.44 The health visitors remained in contact with women on their caseload and there were opportunities for observation and support when the women attended baby clinics, baby massage, or postnatal groups. The women could also ask for further follow-up support when they thought they needed it.

The key to the effect of this psychological approach might therefore lie in the generalisation of the training outcomes across all women on their caseload, beyond the scope for which the training was originally developed, providing benefit from the health visitors’ enhanced input and ongoing supportive engagement.

Potential sources of bias

Over a third (46/125) of women in the control group and over a quarter (61/214) in the intervention group said they had been prescribed an antidepressant, suggesting that the greater improvement in the intervention group was not attributable to a higher rate of prescriptions for antidepressants.

Contrasting benefits of psychologically informed approaches

We found no difference in outcome between the two psychological approaches. This finding is consistent with findings of similar research on psychological therapies that found that different models of intervention result in broadly similar outcomes, despite differences in theoretical bases and style of intervention delivered. This is known as the equivalence paradox.45 For example, a primary care trial for patients with depression, comparing brief non-directive counselling and cognitive behavioural therapy, found no significant difference in outcomes at four months, leading to the conclusion that they were both equally effective in this setting to this follow-up point.7 Similar effects have been found in large datasets comparing person centred therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy in routine NHS primary care settings.46

Further analysis and research

We report separately the results of further analysis for the women with a six week EPDS score <12; infant, partner, and economic outcomes; the views of women using a qualitative approach; and features associated with greater individual improvement.

The trial was not designed to detect the unexpected non-specific effect of the training intervention on the cohort of all women as randomised. This observation should be tested in a trial focused on this issue to determine the mechanism of the effect.

Conclusion

This large trial of treatment for postpartum depression is unique in the comparison of the cognitive behavioural approach and person centred approach. The trial contributes new evidence to indicate that training in psychologically informed approaches can be recommended for health visitors to enable them to identify postnatal depressive symptoms and enhance the psychological care of postnatal women.

What is already known on this topic

Postnatal depression is a global problem that can persist beyond the first postnatal year

There are problems in recognising the condition and difficulties with using antidepressants in postnatal women

Psychologically informed interventions provide a practical, acceptable alternative

What this study adds

Health visitors can be trained to develop skills in the assessment of women and the detection of postnatal depressive symptoms and in the provision of psychologically informed interventions based on person centred or cognitive behavioural principles

The training was effective in reducing the proportion of women with postnatal depressive symptoms at six and 12 months postnatally

Both person centred and cognitive behavioural approaches were equally beneficial in bringing out sustained change in postnatal women

We thank the women, health visitors, general practitioners, and primary care trusts for supporting the trial; the trial advisory group; Trent MREC, David Shapiro, and the training reference group; Mike Campbell and the data monitoring and ethics committee; Tom Ricketts, Keith Tudor, and Chris Williams for their training input; Robin Smith, GIS Analyst; and Mind Garden Inc for permission to use the STAI and Psychological Assessment Resources for permission to use the PSI-SF.

Contributors: CJM prepared the proposal, designed and supervised the conduct of the study, prepared the manuscript, and is guarantor. PS prepared the proposal, advised on design and provided supervision for the local coordinators. RW prepared the proposal and designed and advised on the conduct of the study. GP advised on design and analysed the intervention process monitoring. SD advised on design and participated in the economic analysis and the reporting. SJW provided statistical advice on the proposal at trial advisory group meetings and revised the statistical analysis plan, analysed the data, contributed to the writing. TB prepared the proposal and advised on design. MB advised on design and chaired the trial advisory group. GJP advised on design and planned the statistical analysis. JN contributed to the development of the proposal, advised on design, and assisted with the preparation of the manuscript. All contributors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding and sponsor: The trial was commissioned, funded, and sponsored by the NHS research and development health technology assessment programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Trent multicentre research ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:a3045

References

- 1.Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2005;119:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray L, Cooper PJ. The role of infant and maternal factors in postpartum depression, mother-infant interactions, and infant outcomes. In: Murray L, Cooper P, eds. Postpartum depression and child development. London: Guilford Press, 1997:111-35.

- 3.Lewis G. Why mothers die 2000-2002. The sixth report of confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH, 2004.

- 4.Ballard CG, Davis R, Cullen PC, Mohan RN, Dean C. Prevalence of postnatal psychiatric morbidity in mothers and fathers. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:782-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramchandani P, Stein A, Evans J, O’Connor TG. Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: a prospective study. Lancet 2005;365:2201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedli K, King MB, Lloyd M, Horder J. Randomised controlled assessment of non-directive psychotherapy versus routine general-practitioner care. Lancet 1997;350:1662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward E, King M, Lloyd M, Bower P, Sibbald B, Farrelly S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of non-directive counselling, cognitive-behaviour therapy, and usual general practitioner care for patients with depression. I: clinical effectiveness. BMJ 2000;321:1383-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, Gretton V, Miller P, Palmer B, et al Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ 2001;322:772-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Churchill R, Hunot V, Corney R. A systematic review of controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for depression. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bower P, Rowland N. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of counselling in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffbrand S, Howard L, Crawley H. Antidepressant drug treatment for postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(2):CD002018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appleby L, Warner R, Whitton A, Faragher B. A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioural counselling in the treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ 1997;314:932-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oates MR, Cox JL, Neema P, Asten P, Glangeaud-Freudenthal N, Figueiredo B, et al. Postnatal depression across countries and cultures: a qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry 2004;184(suppl 46):s10-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health. Into the mainstream, implementation plan: mainstreaming gender and women’s mental health. London: Department of Health, 2003.

- 15.Dennis CL, Hodnett E. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD006116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrell CJ. Review of interventions to prevent or treat postnatal depression. Clin Eff Nurs 2006;9(suppl 2):E135-61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark DM, Fairburn CG, eds. Science and practice of cognitive behaviour therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- 19.Sanders P. Mapping person centred approaches to counselling and psychotherapy. Person Centred Practice 2000;8:62-74. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brugha TS, Sturt E, Maccarthy B, Potter J, Wykes T, Bebbington PE. The interview measure of social relationships: the description and evaluation of a survey instrument for assessing personal social resources. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1987;22:123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brugha TS, Cragg D. The list of threatening experiences: the reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990;82:77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8:37-54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerrard J, Holden JM, Elliott SA, McKenzie P, McKenzie J, Cox JL. A trainer’s perspective of an innovative programme teaching health visitors about the detection, treatment and prevention of postnatal depression. J Adv Nurs 1993;18:1825-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holden J. Using the EPDS. In: Cox J, Holden J, eds. Perinatal psychiatry. London: Gaskell, 1994:125-44.

- 25.Tudor K, Wilkins P. What’s in a name? From ‘non-directive therapy’ to person-centred therapy and back again. Seventh World Conference for Person-Centred and Experiential Psychotherapy and Counselling. Potsdam, Germany, 2006.

- 26.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Gandek B. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Boston: Health Institute, 1995.

- 27.Barkham M, Margison F, Leach C, Lucock M, Mellor-Clark J, Evans C. Service profiling and outcomes benchmarking using the CORE-OM: toward practice-based evidence in the psychological therapies. Clinical outcomes in routine evaluation-outcome measures. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69:184-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults. Redwood City: Mind Garden, 1983.

- 29.Brockington IF, Macdonald E, Wainscott G. Anxiety, obsessions and morbid preoccupations in pregnancy and the puerperium. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9:253-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abidin RA. Parenting stress index. 3rd ed. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1995.

- 31.Morrell CJ, Spiby H, Stewart P, Walters S, Morgan A. Costs and benefits of community postnatal support workers: a randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2000;4:1-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- 33.Neal D. Index of multiple deprivation item 5 (IMD) 2004. London: Economic Development Steering Group, 2004.

- 34.Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Antenatal and postnatal mental health. Clinical management and service guidance. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. [PubMed]

- 36.Cooper PJ, Murray L, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression. 1. Impact on maternal mood. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:412-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott S, Henshaw C. Decision to treat. In: Henshaw C, Elliott S, eds. Screening for perinatal depression. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2005:171-99.

- 38.Number needed to treat (NNT). Bandolier 59. www.jr2.ox.ac.UK/bandolier/band59/NNT1.html.

- 39.Holden JM, Sagovsky R, Cox JL. Counselling in a general practice setting: controlled study of health visitor intervention in treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ 1989;298:223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milgrom J, Negri LM, Gemmill AW, McNeil M, Martin PR. A randomised controlled trial of psychological interventions for postnatal depression. Br J Clin Psychol 2005;44:529-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth 2006;33:323-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henshaw CA. What do women think about treatments for postnatal depression? Clinic Eff Nurs 2004;8:170-5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colquitt JA, LePine JA, Noe RA. Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: a meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. J Appl Psychol 2000;85:678-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wills TA. Supportive functions of interpersonal relationships. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, eds. Social support and health. New York: Academic Press, 1985:61-82.

- 45.Stiles WB, Shapiro DA, Elliott R. Are all psychotherapies equivalent? Am Psychol 1986;41:165-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stiles WB, Barkham M, Twigg E, Mellor-Clark J, Cooper M. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural, person-centred, and psychodynamic therapies as practised in UK National Health Service settings. Psychol Med 2006;36:555-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]