Abstract

Background

This paper presents a retrospective statistical study on the newly-released data set by the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium on gene expression in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. This data set contains gene expression data as well as limited demographic and clinical data for each subject. Previous studies using statistical classification or machine learning algorithms have focused on gene expression data only. The present paper investigates if such techniques can benefit from including demographic and clinical data.

Results

We compare six classification algorithms: support vector machines (SVMs), nearest shrunken centroids, decision trees, ensemble of voters, naïve Bayes, and nearest neighbor. SVMs outperform the other algorithms. Using expression data only, they yield an area under the ROC curve of 0.92 for bipolar disorder versus control, and 0.91 for schizophrenia versus control. By including demographic and clinical data, classification performance improves to 0.97 and 0.94 respectively.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates that SVMs can distinguish bipolar disorder and schizophrenia from normal control at a very high rate. Moreover, it shows that classification performance improves by including demographic and clinical data. We also found that some variables in this data set, such as alcohol and drug use, are strongly associated to the diseases. These variables may affect gene expression and make it more difficult to identify genes that are directly associated to the diseases. Stratification can correct for such variables, but we show that this reduces the power of the statistical methods.

Background

The Stanley Neuropathology Consortium [1] recently made a large (over 300 sample) data set publicly available on gene expression in the brains of deceased individuals with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, as well as controls. In addition the data contains limited demographic and clinical history information, including gender and history of smoking, alcohol and drug use. This paper presents a retrospective statistical study on this data set, in which we address the following three questions:

Q1. Can either bipolar disorder or schizophrenia be distinguished from control purely on the basis of gene expression profile?

Q2. Does addition of the demographic and clinical history data further improve the ability to distinguish bipolar disorder or schizophrenia from control?

Q3. Is there a significant difference between the abilities of different widely-used data analysis algorithms to make these distinctions?

We show that bipolar disorder and schizophrenia each can be distinguished from control, based on gene expression alone, significantly better than chance – in fact with areas under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.91 (schizophrenia vs. control) and 0.92 (bipolar disorder vs. control). While area under the ROC curve indicates how well one can distinguish across a range of specificities (with 0.5 being no better than chance and 1.0 being perfect distinction), it is also worth noting that for each task, a sensitivity of 0.85 can be achieved when operating at a specificity of 0.9. Moreover, by taking demographic information and clinical history into account (see Table 1), performance improves to an AUC of 0.94 for schizophrenia vs. control and to an AUC of 0.97 for bipolar disorder vs. control. To our knowledge, this is the first statistical comparison of the efficacy of using a combination of gene expression data and clinical history data against using gene expression data alone. With regard to question Q3, the paper shows that support vector machines (SVMs) significantly outperform the other most widely used algorithms for statistical classification and machine learning for these tasks.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features

| Feature | Value (encoding) | Control | Schiz. | Bipolar |

| Age | 44 ± 8 | 43 ± 9 | 45 ± 10 | |

| Sex | Male (1) | 81 | 86 | 53 |

| Female (-1) | 31 | 29 | 52 | |

| PMI | 29 ± 13 | 31 ± 15 | 38 ± 17 | |

| Brain pH | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | |

| Left brain | Frozen (1) | 51 | 57 | 59 |

| Fixed (-1) | 61 | 58 | 46 | |

| Brain region | FrontalBA46 (1) | 101 | 104 | 94 |

| FrontalBA46/10 (-1) | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| HSV 1 OD Z-score | 0.1 ± 1.0 | -0.2 ± 0.9 | -0.0 ± 0.8 | |

| HSV 2 OD Z-score | -0.2 ± 0.5 | -0.1 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 1.3 | |

| Smoking at TOD | Yes (1) | 29 | 71 | 47 |

| No (-1) | 29 | 19 | 18 | |

| Unknown (0) | 54 | 25 | 40 | |

| Alcohol use | Unknown (1) | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Little or none (2) | 56 | 35 | 12 | |

| Social (3) | 38 | 22 | 24 | |

| Moderate in past (4) | 4 | 10 | 16 | |

| Moderate in present (5) | 8 | 10 | 10 | |

| Heavy in past (6) | 6 | 11 | 16 | |

| Heavy in present (7) | 0 | 27 | 23 | |

| Drug use | Unknown (1) | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Little or none (2) | 97 | 52 | 32 | |

| Social (3) | 7 | 7 | 8 | |

| Moderate in past (4) | 5 | 13 | 21 | |

| Moderate in present (5) | 3 | 8 | 12 | |

| Heavy in past (6) | 0 | 11 | 6 | |

| Heavy in present (7) | 0 | 18 | 26 | |

| Rate of death | Sudden (1) | 110 | 91 | 96 |

| Possible anoxia (2) | 0 | 18 | 6 | |

| Slow death (3) | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| Mechanical ventilator (4) | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

This table lists the distribution (count or mean ± standard deviation) of the demographic features in the three classes (control, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder). Because most classification techniques are restricted to numerical features only, we reencode each nominal feature as a numeric feature. The numerical encoding is listed between parentheses after each nominal feature value.

Furthermore, we found that some variables in this data set, such as alcohol and drug use, are strongly associated to the diseases. Given that these variables may affect gene expression, they may make it more difficult to identify genes that are directly associated to the diseases. (We discuss this point in detail later in the text.) We have investigated if post-stratification can correct for such variables, but we found that it significantly reduces the predictive accuracy of the statistical methods.

Data

The expression data set was obtained from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium [1]. The records utilized in this study are a subset of the entire collection of data. The data set contains 115 schizophrenia patients, 105 patients with bipolar disorder and 112 controls. For each subject, it includes annotated gene expression data and demographic and clinical information. All data was analyzed un-blinded. Diagnosis and criteria have been described previously by Torrey and colleagues [2]. As described in the same report by Torrey and colleagues, the recreational or prescription status of drugs for each of the donors was largely unknown, because the researchers relied on post-mortem urine toxicology screens that are not always conducted.

The expression data was obtained using Affymetrix Human Genome U133A GeneChip oligonucleotide arrays containing 22,283 probe sets (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Probe level data was summarized using the GC content adjusted robust multi-array average (RMA) method [3]. The data set includes the GC-RMA value of each probe set as a numerical feature.

The data set records, besides expression data, also demographic and clinical information about the subjects. Table 1 lists the recorded demographic and clinical features with their distribution in the three classes. For numeric features, it lists the mean and standard deviation, and for nominal features, the class-wise count of each feature value.

Algorithms

We define two binary classification tasks on the data set: schizophrenia versus control and bipolar versus control. For each task, we compare the following six classification techniques: support vector machines, nearest shrunken centroids, decision trees, ensemble of voters, naïve Bayes, and nearest neighbor. We briefly describe each technique. The section "Methods" lists the software packages that we use and explains how the parameters of the different algorithms are set.

Support vector machines

Support vector machines (SVMs, [4]) belong to the family of generalized linear models. We employ linear SVMs, which exhibit good classification performance on gene expression data [5]. A linear SVM is essentially an (n-1)-dimensional hyper-plane that separates the instances of the two classes in the n-dimensional feature space. Figure 1a illustrates this for the two dimensional case: the hyper-plane reduces here to a line, which separates the empty (class 1) and filled (class 2) circles. The hyper-plane maximizes the margin with the closest training instances. These instances are called the "support vectors" because they fix the position and orientation of the hyper-plane. Linear SVMs assume that the training data is linearly separable. If this is not the case, then SVMs rely instead on the concept of a soft margin [6]. In the evaluation, we use a soft margin SVM, which minimizes, in addition to the margin, also the sum of the distances to the training instances that are incorrectly classified by the hyper-plane (the di in Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the (a) support vector machines, (b) nearest shrunken centroids, (c) decision trees, and (d) nearest neighbor methods.

Nearest shrunken centroids

Nearest shrunken centroids (NSC, [7]) is a technique designed for classifying gene expression data. NSC represents each class by its centroid (mean feature vector) and classifies new instances by assigning them the class of the closest centroid. NSC shrinks the class centroids (ci in Figure 1b) in the direction of the overall data centroid. This has the effect that components of a class centroid that after shrinkage are equal to the corresponding components of the overall centroid become irrelevant to the classification process. This occurs for the horizontal component of the class centroids in Figure 1b. As a result, NSC implicitly performs a kind of feature selection.

Decision trees

Decision trees (DTs, [8]) are tree-shaped symbolic models with tests on the feature values in the internal nodes, and class labels in the leaves (Figure 1c). DTs classify a new instance by sorting it down the tree, according to the tests in the nodes, until it reaches a leaf; the label of the leaf becomes the predicted class of the new instance. C4.5 [8] is a well-known algorithm for constructing decision trees. C4.5 builds a DT top-down, by recursively partitioning the data at each step by a test comparing a feature to a value. At each node, the algorithm selects the test that maximizes a heuristic function called information gain ratio. The better a test is able to separate the instances of the two classes, the higher its information gain ratio. Then, it partitions the training instances based on the selected test, and finally it recursively repeats the same procedure to construct a sub-tree for each subset in the partition. C4.5 creates a leaf if all remaining instances belong to the same class or if there are fewer instances than a user defined threshold. The label of the leaf is the majority class of the instances it covers. After building the tree, C4.5 prunes back some parts to reduce the expected error on new instances.

Ensemble of voters

Ensemble of voters (EOV, [9]) is a simple ensemble method. An EOV model is a set of decision stumps. Decision stumps are decision trees that consist of precisely one test node with two leaves. The EOV model includes one decision stump for each of the top N feature value tests ranked by the information gain score [8]. To obtain a prediction for a new instance, the model combines the predictions of the stumps by means of majority voting: the predicted class is the class predicted by more than N/2 stumps.

Naïve Bayes

Naïve Bayes (NB, [10]) is a statistical classifier based on Bayes rule. Its name comes from the strong (naïve) statistical independence assumptions that it makes. In spite of these strong assumptions, it often works remarkably well in practice. NB predicts a class with the rule: . It estimates P(c) and P(featurei = valuei|c) from the training data. Note that NB assumes nominal features, which means that numerical features must be discretized prior to running NB.

Nearest neighbor

k-nearest neighbor (kNN, [11]) classifies a new instance as the majority class of its k closest training instances in the feature space. For example, 3NN in Figure 1d assigns the class "black" to the new instance (indicated with a triangle).

Evaluation

We evaluate the performance of the different classification techniques by means of Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. ROC analysis allows us to simultaneously compare classifiers for different misclassification costs and class distributions [12]. It is based on the notions of "true positive rate" (TP, also known as sensitivity or recall) and "false positive rate" (FP, also known as 1.0 – specificity). Given two classes "positive" and "negative", TP rate is the proportion of correctly predicted positive examples, and FP rate is the proportion of negative examples that are incorrectly predicted positive. The vertical axis of a ROC diagram represents TP rate, and the horizontal axis FP rate. Each classifier corresponds to a point on this diagram. The closer the point is to the upper-left corner (TP rate = 1, FP rate = 0), the better the classifier.

Most classifiers provide confidence scores for their predictions. For such classifiers, a ROC curve can be constructed. We present such a curve for each classifier and report the corresponding "area under curve" (AUC), which is defined as the area between the ROC curve and the horizontal axis. To obtain a measure for the predictive performance of the models, we estimate the ROC curves using a 10-fold cross validation procedure. Details about this evaluation procedure can be found in the section "Methods". We use a t-test to assess if the AUC difference between two classifiers is significant and report the corresponding p-value.

Results and discussion

Classifier performance

We compare the six classification techniques in the context of two classification tasks: schizophrenia versus control and bipolar versus control. In a first set of experiments, the data consist of only the gene expression features (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), and in a second batch, the data include both demographic and clinical features as well as gene expression (Figures 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

Figure 2.

ROC curves, schizophrenia/control, expression data.

Figure 3.

ROC curves, schizophrenia/control, expression data, male subjects.

Figure 4.

ROC curves, schizophrenia/control, expression data, female subjects.

Figure 5.

ROC curves, bipolar/control, expression data.

Figure 6.

ROC curves, bipolar/control, expression data, male subjects.

Figure 7.

ROC curves, bipolar/control, expression data, female subjects.

Figure 8.

ROC curves, schizophrenia/control, demographic, clinical, and expression data.

Figure 9.

ROC curves, schizophrenia/control, all data, male subjects.

Figure 10.

ROC curves, schizophrenia/control, all data, female subjects.

Figure 11.

ROC curves, bipolar/control, demographic, clinical, and expression data.

Figure 12.

ROC curves, bipolar/control, all data, male subjects.

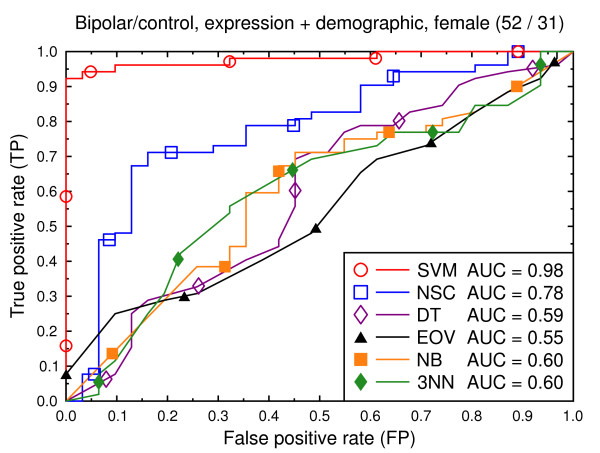

Figure 13.

ROC curves, bipolar/control, all data, female subjects.

Figure 2 compares the classification techniques for the schizophrenia versus control task, using only the gene expression data. SVM outperforms the other techniques. It yields a cross validated AUC of 0.91, which is significantly better than NSC (AUC = 0.71, p = 0.002), DT (AUC = 0.64, p = 0.0001), EOV (AUC = 0.71, p = 0.0001), NB (AUC = 0.71, p = 0.0004), and 3NN (AUC = 0.70, p = 0.0002). The same holds for the bipolar versus control task (Figure 5). SVM (AUC = 0.92) outperforms the other techniques. The second best technique is NSC (AUC = 0.73, p = 0.01).

We also present experiments on data for male subjects only (Figure 3 and Figure 6) and for female subjects only (Figure 4 and Figure 7), to assess if the diseases can be better predicted if data of only one sex is used. The SVM result AUC = 0.91 on the combined data of Figure 2 for schizophrenia versus control is, however, not significantly different from the result for male subjects (Figure 3, AUC = 0.92, p = 0.9) or that for female subjects (Figure 4, AUC = 0.87, p = 0.4). The same holds for the bipolar versus control task. We hypothesize that this is because the data sets with subjects of one sex only are much smaller than the combined data, so that there is less training data for each model. Even if classification is easier for such data, this is offset by the smaller data size.

Figures 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 present a similar set of experiments for the data set that includes demographic and clinical data in addition to the gene expression data. Adding demographic and clinical information improves classification performance. SVM, for example, performs better on the schizophrenia versus control task with demographic information (Figure 8, AUC = 0.94) than without such additional information (Figure 2, AUC = 0.91, p = 0.06). The same holds for the other classification techniques and for the bipolar versus control task (Figure 11 versus Figure 5).

We again present experiments for male and female subjects separately (Figures 9, 10, 12 and 13), this time with the demographic and clinical data included. The conclusion from this set of experiments is similar to the previous conclusion: separating the subjects by sex does not significantly improve the classification performance for SVMs.

The superior performance of SVMs when compared to the other classification algorithms can be understood based on the properties of gene expression data. Gene expression data is typically characterized by a high dimension combined with a relatively low number of samples. For example, the present data set records the expression level of 22,283 probe sets for a number of samples that is two orders of magnitude smaller. Many classification algorithms are known to perform poorly on such high dimensional data. SVMs, on the other hand, are well suited to this setting because their classification performance can be independent of the dimensionality of the feature set [13]: their performance rather depends on the margin with which they separate the samples (Figure 1a). This explains the good performance of SVMs on high dimensional data. Additional empirical evidence is that SVMs are known to perform well on text classification problems (where each word in the vocabulary represents a dimension) [13]. Previous studies on gene expression data also illustrate the good performance of SVMs [5,9].

Note that the above discussion does not imply that SVMs will always outperform other algorithms on gene expression data. For example, NSC, which implicitly performs dimensionality reduction (recall that it shrinks the class centroids towards the overall data centroid), has also been shown to work well on gene expression data [7,9]. Therefore, it is common practice in machine learning to evaluate different classification algorithms on a new data set and based on this evaluation select the one that works best. This is also the approach that we follow in this work.

Most relevant features

To asses which features are most relevant to each of the classification tasks, we apply two techniques: (a) ranking the features by their p-value, and (b) ranking the features by their SVM weight. The first technique performs, for each feature, a two-sided t-test comparing the feature's values in the two classes. It then ranks the features by their t-test's p-value. Besides the p-values, we also report q-values [14]. q-values measure significance in terms of the false discovery rate. For example, if all features with a q-value ≤ 5% are called significant, then 5% of these features may be false discoveries, that is, their mean value in the two classes may be actually identical. We use the software QVALUE developed by Storey [15] to compute the q-values. The second technique ranks the features by the weight that the SVM classifier assigns to each feature in the linear equation of its classification hyper-plane. The larger the absolute value of the SVM weight, the more important the feature is to the classification task.

The QVALUE software computes, in addition to the q-values, also an estimate of the proportion π0 of truly null features. For each of the schizophrenia versus control tasks it estimates π0 to be 1.0, that is, no significant features; for the bipolar versus control tasks, π0 ranges from 0.54 to 0.72. Note that the estimate for schizophrenia versus control is conservative (an overestimate). QVALUE makes certain assumptions about the p-value distribution of the data, which do not hold in this case (cf. Figure 14). It is interesting that, even though QVALUE estimates that there are no significant individual features, it is still possible to build classification models that are highly accurate on previously unseen data. (Recall that SVM yields a cross-validated AUC of 0.91 for schizophrenia versus control.) This is partly because the QVALUE estimate is conservative. But it also is partly because classification techniques do not rely on a single feature, but exploit the combined effect of the set of most relevant features. Therefore, obtaining an accurate classifier is possible even if there are no individual significant features.

Figure 14.

p-value histogram for (a) schizophrenia/control and (b) bipolar/control (expression data, all subjects). p-values of truly null features are distributed uniformly, while p-values of significant features are clustered around 0.0. This translates to a flat histogram with a peak at 0.0, as in (b). The p-values in (a) are biased towards 1.0 causing the q-value estimates to be conservative. The reason for observing such biased distributions is currently not very well understood [59].

Table 2 (schizophrenia versus control) and Table 3 (bipolar versus control) rank the features by p-value. The left panel of each table shows results based on expression data only; the right panel presents results that include the demographic and clinical features as well. Each table consists of three parts: the top part contains the rankings for all subjects combined, the middle part the male subjects' rankings, and the bottom part the female subjects' rankings.(see additional file 3)

Table 2.

Genes sorted by p-value, schizophrenia versus control

| Expression data only | Demographic, clinical, and expression data | ||||||||

| All subjects | All subjects | ||||||||

| p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol | p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol |

| 3.92E-08 | 8.74E-04 | 221011_s_at | NM_030915 | LBH | 1.39E-10 | 3.11E-06 | Drug use | ||

| 1.02E-07 | 1.13E-03 | 204326_x_at | NM_002450 | MT1X | 2.88E-09 | 3.21E-05 | Alcohol use | ||

| 2.47E-07 | 1.84E-03 | 208581_x_at | NM_005952 | MT1X | 3.92E-08 | 2.92E-04 | 221011_s_at | NM_030915 | LBH |

| 6.37E-07 | 3.55E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 | 1.02E-07 | 5.67E-04 | 204326_x_at | NM_002450 | MT1X |

| 1.73E-06 | 6.20E-03 | 209735_at | AF098951 | ABCG2 | 2.47E-07 | 1.10E-03 | 208581_x_at | NM_005952 | MT1X |

| 1.91E-06 | 6.20E-03 | 212859_x_at | BF217861 | MT1E | 6.37E-07 | 2.37E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 |

| 1.95E-06 | 6.20E-03 | 205208_at | NM_012190 | ALDH1L1 | 1.73E-06 | 4.83E-03 | 209735_at | AF098951 | ABCG2 |

| 2.77E-06 | 7.73E-03 | 209959_at | U12767 | NR4A3 | 1.91E-06 | 4.83E-03 | 212859_x_at | BF217861 | MT1E |

| 3.25E-06 | 8.04E-03 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST | 1.95E-06 | 4.83E-03 | 205208_at | NM_012190 | ALDH1L1 |

| 6.39E-06 | 1.37E-02 | 207547_s_at | NM_007177 | FAM107A | 2.77E-06 | 6.19E-03 | 209959_at | U12767 | NR4A3 |

| 6.96E-06 | 1.37E-02 | 205984_at | NM_001882 | CRHBP | 3.25E-06 | 6.59E-03 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST |

| 7.36E-06 | 1.37E-02 | 221950_at | AI478455 | EMX2 | 6.39E-06 | 1.13E-02 | 207547_s_at | NM_007177 | FAM107A |

| 9.28E-06 | 1.59E-02 | 206001_at | NM_000905 | NPY | 6.96E-06 | 1.13E-02 | 205984_at | NM_001882 | CRHBP |

| 1.02E-05 | 1.63E-02 | 212185_x_at | NM_005953 | MT2A | 7.36E-06 | 1.13E-02 | 221950_at | AI478455 | EMX2 |

| 1.61E-05 | 2.39E-02 | 209047_at | AL518391 | AQP1 | 7.62E-06 | 1.13E-02 | Smoking at TOD | ||

| 1.75E-05 | 2.44E-02 | 206461_x_at | NM_005951 | MT1H/P2 | 9.28E-06 | 1.29E-02 | 206001_at | NM_000905 | NPY |

| 2.06E-05 | 2.69E-02 | 202936_s_at | NM_000346 | SOX9 | 1.02E-05 | 1.34E-02 | 212185_x_at | NM_005953 | MT2A |

| 2.96E-05 | 3.50E-02 | 202917_s_at | NM_002964 | S100A8 | 1.61E-05 | 1.99E-02 | 209047_at | AL518391 | AQP1 |

| 2.98E-05 | 3.50E-02 | 213791_at | NM_006211 | PENK | 1.75E-05 | 2.06E-02 | 206461_x_at | NM_005951 | MT1H/P2 |

| 3.43E-05 | 3.82E-02 | 205630_at | NM_000756 | CRH | 2.06E-05 | 2.29E-02 | 202936_s_at | NM_000346 | SOX9 |

| Male subjects | Male subjects | ||||||||

| 1.21E-09 | 2.69E-05 | 206001_at | NM_000905 | NPY | 2.42E-10 | 5.40E-06 | Drug use | ||

| 1.18E-08 | 1.31E-04 | 205984_at | NM_001882 | CRHBP | 1.21E-09 | 1.33E-05 | 206001_at | NM_000905 | NPY |

| 4.06E-08 | 3.01E-04 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST | 1.79E-09 | 1.33E-05 | Alcohol use | ||

| 1.47E-07 | 8.22E-04 | 204326_x_at | NM_002450 | MT1X | 1.18E-08 | 6.56E-05 | 205984_at | NM_001882 | CRHBP |

| 1.98E-07 | 8.81E-04 | 221011_s_at | NM_030915 | LBH | 2.39E-08 | 1.06E-04 | Brain pH | ||

| 3.41E-07 | 1.26E-03 | 208581_x_at | NM_005952 | MT1X | 4.06E-08 | 1.51E-04 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST |

| 8.38E-07 | 2.67E-03 | 217911_s_at | NM_004281 | BAG3 | 1.47E-07 | 4.70E-04 | 204326_x_at | NM_002450 | MT1X |

| 1.11E-06 | 3.10E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 | 1.98E-07 | 5.51E-04 | 221011_s_at | NM_030915 | LBH |

| 3.01E-06 | 7.27E-03 | 205336_at | NM_002854 | PVALB | 3.41E-07 | 8.44E-04 | 208581_x_at | NM_005952 | MT1X |

| 3.26E-06 | 7.27E-03 | 212859_x_at | BF217861 | MT1E | 8.38E-07 | 1.87E-03 | 217911_s_at | NM_004281 | BAG3 |

| 3.72E-06 | 7.54E-03 | 209735_at | AF098951 | ABCG2 | 1.11E-06 | 2.26E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 |

| 4.18E-06 | 7.76E-03 | 220045_at | NM_022728 | NEUROD6 | 3.01E-06 | 5.59E-03 | 205336_at | NM_002854 | PVALB |

| 5.00E-06 | 8.00E-03 | 221950_at | AI478455 | EMX2 | 3.26E-06 | 5.59E-03 | 212859_x_at | BF217861 | MT1E |

| 5.03E-06 | 8.00E-03 | 202936_s_at | NM_000346 | SOX9 | 3.72E-06 | 5.93E-03 | 209735_at | AF098951 | ABCG2 |

| 5.41E-06 | 8.04E-03 | 211725_s_at | BC005884 | BID | 4.18E-06 | 6.21E-03 | 220045_at | NM_022728 | NEUROD6 |

| 6.56E-06 | 8.98E-03 | 202071_at | NM_002999 | SDC4 | 5.00E-06 | 6.59E-03 | 221950_at | AI478455 | EMX2 |

| 6.85E-06 | 8.98E-03 | 212185_x_at | NM_005953 | MT2A | 5.03E-06 | 6.59E-03 | 202936_s_at | NM_000346 | SOX9 |

| 8.18E-06 | 1.01E-02 | 202917_s_at | NM_002964 | S100A8 | 5.41E-06 | 6.70E-03 | 211725_s_at | BC005884 | BID |

| 1.04E-05 | 1.22E-02 | 206461_x_at | NM_005951 | MT1H/P2 | 6.56E-06 | 7.63E-03 | 202071_at | NM_002999 | SDC4 |

| 1.27E-05 | 1.34E-02 | 206670_s_at | NM_013445 | GAD1 | 6.85E-06 | 7.63E-03 | 212185_x_at | NM_005953 | MT2A |

| Female subjects | Female subjects | ||||||||

| 4.72E-04 | 1.00E+00 | 201041_s_at | NM_004417 | DUSP1 | 4.72E-04 | 1.00E+00 | 201041_s_at | NM_004417 | DUSP1 |

| 8.02E-04 | 1.00E+00 | 208078_s_at | NM_030751 | SNF1LK | 5.93E-04 | 1.00E+00 | Age | ||

| 1.04E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 221841_s_at | BF514079 | KLF4 | 8.02E-04 | 1.00E+00 | 208078_s_at | NM_030751 | SNF1LK |

| 1.35E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 201865_x_at | AI432196 | NR3C1 | 1.04E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 221841_s_at | BF514079 | KLF4 |

| 1.85E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 219044_at | NM_018271 | THNSL2 | 1.35E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 201865_x_at | AI432196 | NR3C1 |

| 2.53E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 202393_s_at | NM_005655 | KLF10 | 1.85E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 219044_at | NM_018271 | THNSL2 |

| 3.16E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 209189_at | BC004490 | FOS | 2.53E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 202393_s_at | NM_005655 | KLF10 |

| 4.09E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 201417_at | AL136179 | SOX4 | 2.81E-03 | 1.00E+00 | Smoking at TOD | ||

| 6.61E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 211671_s_at | U01351 | NR3C1 | 3.16E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 209189_at | BC004490 | FOS |

| 7.38E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 209457_at | U16996 | DUSP5 | 4.09E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 201417_at | AL136179 | SOX4 |

| 9.32E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 205856_at | NM_015865 | SLC14A1 | 6.61E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 211671_s_at | U01351 | NR3C1 |

| 9.73E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 213164_at | AI867198 | SLC5A3 | 7.38E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 209457_at | U16996 | DUSP5 |

| 1.24E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 214686_at | AA868898 | ZNF266 | 9.32E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 205856_at | NM_015865 | SLC14A1 |

| 1.26E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 201464_x_at | BG491844 | JUN | 9.73E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 213164_at | AI867198 | SLC5A3 |

| 1.26E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 209900_s_at | AL162079 | SLC16A1 | 1.24E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 214686_at | AA868898 | ZNF266 |

| 1.28E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 205249_at | NM_000399 | EGR2 | 1.26E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 201464_x_at | BG491844 | JUN |

| 1.39E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 200664_s_at | BG537255 | DNAJB1 | 1.26E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 209900_s_at | AL162079 | SLC16A1 |

| 1.62E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 202234_s_at | BF511091 | SLC16A1 | 1.28E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 205249_at | NM_000399 | EGR2 |

| 1.65E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 207547_s_at | NM_007177 | FAM107A | 1.39E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 200664_s_at | BG537255 | DNAJB1 |

| 1.71E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 208691_at | BC001188 | TFRC | 1.62E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 202234_s_at | BF511091 | SLC16A1 |

Table 3.

Genes sorted by p-value, bipolar versus control

| Expression data only | Demographic, clinical, and expression data | ||||||||

| All subjects | All subjects | ||||||||

| p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol | p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol |

| 1.37E-09 | 2.19E-05 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST | 2.92E-18 | 4.66E-14 | Drug use | ||

| 1.13E-06 | 5.75E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 | 7.09E-13 | 5.66E-09 | Alcohol use | ||

| 1.39E-06 | 5.75E-03 | 204185_x_at | NM_005038 | PPID | 1.37E-09 | 7.31E-06 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST |

| 1.44E-06 | 5.75E-03 | 208290_s_at | NM_001969 | EIF5 | 1.13E-06 | 3.83E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 |

| 2.48E-06 | 7.93E-03 | 210285_x_at | BC000383 | WTAP | 1.39E-06 | 3.83E-03 | 204185_x_at | NM_005038 | PPID |

| 3.16E-06 | 8.42E-03 | 220045_at | NM_022728 | NEUROD6 | 1.44E-06 | 3.83E-03 | 208290_s_at | NM_001969 | EIF5 |

| 3.88E-06 | 8.68E-03 | 211725_s_at | BC005884 | BID | 2.48E-06 | 5.67E-03 | 210285_x_at | BC000383 | WTAP |

| 4.35E-06 | 8.68E-03 | 208687_x_at | AF352832 | HSPA8 | 3.16E-06 | 6.32E-03 | 220045_at | NM_022728 | NEUROD6 |

| 5.27E-06 | 9.04E-03 | 212724_at | BG054844 | RND3 | 3.88E-06 | 6.88E-03 | 211725_s_at | BC005884 | BID |

| 5.94E-06 | 9.04E-03 | 200881_s_at | NM_001539 | DNAJA1 | 4.35E-06 | 6.94E-03 | 208687_x_at | AF352832 | HSPA8 |

| 6.72E-06 | 9.04E-03 | 221011_s_at | NM_030915 | LBH | 5.27E-06 | 7.66E-03 | 212724_at | BG054844 | RND3 |

| 6.89E-06 | 9.04E-03 | 203087_s_at | NM_004520 | KIF2A | 5.94E-06 | 7.84E-03 | 200881_s_at | NM_001539 | DNAJA1 |

| 7.36E-06 | 9.04E-03 | 208708_x_at | AL080102 | EIF5 | 6.72E-06 | 7.84E-03 | 221011_s_at | NM_030915 | LBH |

| 8.63E-06 | 9.85E-03 | 209619_at | K01144 | CD74 | 6.89E-06 | 7.84E-03 | 203087_s_at | NM_004520 | KIF2A |

| 9.92E-06 | 1.01E-02 | 217932_at | NM_015971 | MRPS7 | 7.36E-06 | 7.84E-03 | 208708_x_at | AL080102 | EIF5 |

| 1.01E-05 | 1.01E-02 | 206001_at | NM_000905 | NPY | 8.63E-06 | 8.62E-03 | 209619_at | K01144 | CD74 |

| 1.09E-05 | 1.01E-02 | 213038_at | AL031602 | RNF19B | 9.92E-06 | 9.00E-03 | 217932_at | NM_015971 | MRPS7 |

| 1.15E-05 | 1.01E-02 | 204122_at | NM_003332 | TYROBP | 1.01E-05 | 9.00E-03 | 206001_at | NM_000905 | NPY |

| 1.20E-05 | 1.01E-02 | 212861_at | BF690150 | MFSD5 | 1.09E-05 | 9.11E-03 | 213038_at | AL031602 | RNF19B |

| 1.47E-05 | 1.17E-02 | 211990_at | M27487 | HLA-DPA1 | 1.15E-05 | 9.11E-03 | 204122_at | NM_003332 | TYROBP |

| Male subjects | Male subjects | ||||||||

| 5.38E-07 | 7.90E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 | 1.68E-12 | 2.47E-08 | Drug use | ||

| 1.14E-05 | 8.36E-02 | 210982_s_at | M60333 | HLA-DRA | 4.55E-10 | 3.34E-06 | Alcohol use | ||

| 2.96E-05 | 1.08E-01 | 219525_at | NM_018242 | SLC47A1 | 5.38E-07 | 2.63E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 |

| 3.21E-05 | 1.08E-01 | 205859_at | NM_004271 | LY86 | 1.14E-05 | 4.18E-02 | 210982_s_at | M60333 | HLA-DRA |

| 3.66E-05 | 1.08E-01 | 208894_at | M60334 | HLA-DRA | 2.96E-05 | 7.68E-02 | 219525_at | NM_018242 | SLC47A1 |

| 6.47E-05 | 1.34E-01 | 204239_s_at | NM_005386 | NNAT | 3.21E-05 | 7.68E-02 | 205859_at | NM_004271 | LY86 |

| 7.61E-05 | 1.34E-01 | 220045_at | NM_022728 | NEUROD6 | 3.66E-05 | 7.68E-02 | 208894_at | M60334 | HLA-DRA |

| 8.23E-05 | 1.34E-01 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST | 6.47E-05 | 1.10E-01 | 204239_s_at | NM_005386 | NNAT |

| 8.23E-05 | 1.34E-01 | 201720_s_at | AI589086 | LAPTM5 | 7.61E-05 | 1.10E-01 | 220045_at | NM_022728 | NEUROD6 |

| 1.12E-04 | 1.65E-01 | 205984_at | NM_001882 | CRHBP | 8.23E-05 | 1.10E-01 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST |

| 1.37E-04 | 1.82E-01 | 204174_at | NM_001629 | ALOX5AP | 8.23E-05 | 1.10E-01 | 201720_s_at | AI589086 | LAPTM5 |

| 1.57E-04 | 1.82E-01 | 209619_at | K01144 | CD74 | 1.12E-04 | 1.38E-01 | 205984_at | NM_001882 | CRHBP |

| 1.61E-04 | 1.82E-01 | 204981_at | NM_002555 | SLC22A18 | 1.37E-04 | 1.55E-01 | 204174_at | NM_001629 | ALOX5AP |

| 1.83E-04 | 1.92E-01 | 205404_at | NM_005525 | HSD11B1 | 1.57E-04 | 1.58E-01 | 209619_at | K01144 | CD74 |

| 1.99E-04 | 1.95E-01 | 204122_at | NM_003332 | TYROBP | 1.61E-04 | 1.58E-01 | 204981_at | NM_002555 | SLC22A18 |

| 2.84E-04 | 2.61E-01 | 211991_s_at | M27487 | HLA-DPA1 | 1.83E-04 | 1.68E-01 | 205404_at | NM_005525 | HSD11B1 |

| 3.06E-04 | 2.65E-01 | 204670_x_at | NM_002125 | HLA-DRB1 | 1.99E-04 | 1.68E-01 | 204122_at | NM_003332 | TYROBP |

| 4.02E-04 | 3.23E-01 | 220052_s_at | NM_012461 | TINF2 | 2.06E-04 | 1.68E-01 | Brain pH | ||

| 4.18E-04 | 3.23E-01 | 206001_at | NM_000905 | NPY | 2.84E-04 | 2.20E-01 | 211991_s_at | M27487 | HLA-DPA1 |

| 4.56E-04 | 3.26E-01 | 207238_s_at | NM_002838 | PTPRC | 3.06E-04 | 2.25E-01 | 204670_x_at | NM_002125 | HLA-DRB1 |

| Female subjects | Female subjects | ||||||||

| 4.27E-05 | 3.21E-01 | 221911_at | BE881590 | ETV1 | 3.19E-08 | 3.84E-04 | Drug use | ||

| 1.55E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 217828_at | NM_024755 | SLTM | 6.64E-06 | 4.00E-02 | Age | ||

| 1.55E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 200881_s_at | NM_001539 | DNAJA1 | 4.27E-05 | 1.71E-01 | 221911_at | BE881590 | ETV1 |

| 1.72E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 201170_s_at | NM_003670 | BHLHB2 | 1.55E-04 | 3.00E-01 | 217828_at | NM_024755 | SLTM |

| 1.74E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 217741_s_at | AW471220 | ZFAND5 | 1.55E-04 | 3.00E-01 | 200881_s_at | NM_001539 | DNAJA1 |

| 2.52E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 212724_at | BG054844 | RND3 | 1.72E-04 | 3.00E-01 | 201170_s_at | NM_003670 | BHLHB2 |

| 2.54E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 212514_x_at | R60068 | DDX3X | 1.74E-04 | 3.00E-01 | 217741_s_at | AW471220 | ZFAND5 |

| 3.26E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 206302_s_at | NM_019094 | NUDT4(P1) | 2.52E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 212724_at | BG054844 | RND3 |

| 3.34E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208891_at | BC003143 | DUSP6 | 2.54E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 212514_x_at | R60068 | DDX3X |

| 4.26E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208687_x_at | AF352832 | HSPA8 | 3.09E-04 | 3.21E-01 | Left brain | ||

| 4.28E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 203087_s_at | NM_004520 | KIF2A | 3.26E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 206302_s_at | NM_019094 | NUDT4(P1) |

| 5.96E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208893_s_at | BC005047 | DUSP6 | 3.34E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208891_at | BC003143 | DUSP6 |

| 6.16E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 210285_x_at | BC000383 | WTAP | 4.26E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208687_x_at | AF352832 | HSPA8 |

| 6.22E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208852_s_at | AI761759 | CANX | 4.28E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 203087_s_at | NM_004520 | KIF2A |

| 6.78E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208892_s_at | BC003143 | DUSP6 | 5.96E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208893_s_at | BC005047 | DUSP6 |

| 6.82E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 205251_at | NM_022817 | PER2 | 6.16E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 210285_x_at | BC000383 | WTAP |

| 7.09E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 200033_at | NM_004396 | DDX5 | 6.22E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208852_s_at | AI761759 | CANX |

| 7.33E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 201604_s_at | NM_002480 | PPP1R12A | 6.78E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 208892_s_at | BC003143 | DUSP6 |

| 7.45E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 204185_x_at | NM_005038 | PPID | 6.82E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 205251_at | NM_022817 | PER2 |

| 7.52E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 204547_at | NM_006822 | RAB40B | 7.09E-04 | 3.21E-01 | 200033_at | NM_004396 | DDX5 |

Comparing (a) the rankings for expression data only (the left panels of the tables) to (b) the rankings for expression and demographic data (the right panels) shows that similar features appear in (a) and (b). For example, all probe sets that appear in (b) also appear in (a) for Table 2, all subjects. In addition, (b) also includes a number of highly ranked demographic and clinical features. Table 2 shows, for example, that drug use and alcohol use are ranked high for the all and male subjects cases. This indicates that some of the demographic and clinical features are important to the classification tasks. Note that we also observed this while comparing classification models: the models with demographic and clinical features are more accurate.

When comparing the features that appear in the different tables, we observe that for the schizophrenia versus control task (Table 2, expression data), the rankings for all subjects and male subjects have 14 features in common: LBH [GenBank:NM_030915], MT1X [GenBank:NM_002450], MT1X [GenBank:NM_005952], TNFSF10 [GenBank:NM_003810], ABCG2 [GenBank:AF098951], MT1E [GenBank:BF217861], SST [GenBank:NM_001048], CRHBP [GenBank:NM_001882], EMX2 [GenBank:AI478455], NPY [GenBank:NM_000905], MT2A [GenBank:NM_005953], MT1H/P2 [GenBank:NM_005951], SOX9 [GenBank:NM_000346], S100A8 [GenBank:NM_002964].

On the other hand, the rankings for all subjects and female subjects have only one feature (FAM107A [GenBank:NM_007177]) in common. For the bipolar versus control task (Table 3, expression data) all subjects and male subjects share 6 features (SST [GenBank:NM_001048], TNFSF10 [GenBank:NM_003810], NEUROD6 [GenBank:NM_022728], CD74 [GenBank:K01144], NPY [GenBank:NM_000905], TYROBP [GenBank:NM_003332]), and all subjects and female subjects also share 6 features (PPID [GenBank:NM_005038], WTAP [GenBank:BC000383], RND3 [GenBank:BG054844], DNAJA1 [GenBank:NM_001539], KIF2A [GenBank:NM_004520]). For both diseases, there is no overlap between the ranking for the female subjects and that for the male subjects. Possibly of higher interest are the features relevant to both the schizophrenia versus control and bipolar versus control tasks. Comparing the rankings (the top left rankings of Table 2 and Table 3) shows that there are 4 common features: LBH [GenBank:NM_030915], TNFSF10 [GenBank:NM_003810], SST [GenBank:NM_001048], and NPY [GenBank:NM_000905]. These are relevant to both diseases.

Table 4 and Table 5 show rankings based on SVM weights. Also here the relevant features observed for expression and demographic data are similar to those found for expression data only. There is also overlap between the rankings for the different subject subsets (all, male only, and female only). Note, however, that the features identified with the SVM weights are different from those identified with the p-value method. Consider the expression data only, all subjects rankings. For schizophrenia versus control, there are no common features in the rankings produced by the p-value method (Table 2) and the SVM method (Table 4). For bipolar versus control (Tables 3 and 5), there are two shared features: SST [GenBank:NM_001048] and LBH [GenBank:NM_030915]. This difference in rankings arises because the methods essentially have a different goal: the p-value method looks for individual features that distinguish the two classes while the SVM method yields a set of features that together distinguish the classes.

Table 4.

Genes sorted by SVM weight, schizophrenia versus control

| Expression data only | Demographic, clinical, and expression data | ||||||||||

| All subjects | All subjects | ||||||||||

| SVM-weight | p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol | SVM-weight | p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol |

| -6.70E-02 | 1.13E-03 | 2.46E-01 | 201137_s_at | NM_002121 | HLA-DPB1 | 1.06E-01 | 1.39E-10 | 3.11E-06 | Drug use | ||

| 5.99E-02 | 4.71E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 214877_at | BE794663 | CDKAL1 | 6.74E-02 | 2.88E-09 | 3.21E-05 | Alcohol use | ||

| -5.62E-02 | 1.19E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 218948_at | AL136679 | QRSL1 | 5.16E-02 | 4.71E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 214877_at | BE794663 | CDKAL1 |

| -5.50E-02 | 5.31E-05 | 4.79E-02 | 203851_at | NM_002178 | IGFBP6 | -5.07E-02 | 5.31E-05 | 4.30E-02 | 203851_at | NM_002178 | IGFBP6 |

| -5.29E-02 | 6.22E-03 | 5.62E-01 | 204545_at | NM_000287 | PEX6 | -5.05E-02 | 6.22E-03 | 5.51E-01 | 204545_at | NM_000287 | PEX6 |

| 5.21E-02 | 1.17E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 202944_at | NM_000262 | NAGA | -4.84E-02 | 1.19E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 218948_at | AL136679 | QRSL1 |

| -4.83E-02 | 7.19E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 201123_s_at | NM_001970 | EIF5A | 4.60E-02 | 1.17E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 202944_at | NM_000262 | NAGA |

| 4.79E-02 | 7.06E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 210075_at | AF151074 | 2-Mar | 4.57E-02 | 9.84E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 206785_s_at | NM_002260 | KLRC2/1 |

| 4.76E-02 | 7.70E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 204418_x_at | NM_000848 | GSTM2 | -4.56E-02 | 1.13E-03 | 2.35E-01 | 201137_s_at | NM_002121 | HLA-DPB1 |

| 4.76E-02 | 6.82E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 204550_x_at | NM_000561 | GSTM1 | -4.55E-02 | 5.69E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 |

| -4.64E-02 | 9.14E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 218051_s_at | NM_022908 | NT5DC2 | 4.51E-02 | 7.06E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 210075_at | AF151074 | 2-Mar |

| -4.56E-02 | 6.35E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 218002_s_at | NM_004887 | CXCL14 | -4.38E-02 | 5.28E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 219592_at | NM_024596 | MCPH1 |

| 4.52E-02 | 9.84E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 206785_s_at | NM_002260 | KLRC2/1 | -4.31E-02 | 4.12E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 205145_s_at | NM_002477 | MYL5 |

| -4.48E-02 | 9.45E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 204295_at | NM_003172 | SURF1 | -4.23E-02 | 2.78E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 206108_s_at | NM_006275 | SFRS6 |

| -4.47E-02 | 2.78E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 206108_s_at | NM_006275 | SFRS6 | 4.15E-02 | 6.82E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 204550_x_at | NM_000561 | GSTM1 |

| 4.45E-02 | 3.91E-03 | 4.65E-01 | 212854_x_at | AB051480 | NBPF10 | 4.14E-02 | 3.91E-03 | 4.54E-01 | 212854_x_at | AB051480 | NBPF10 |

| -4.37E-02 | 5.28E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 219592_at | NM_024596 | MCPH1 | -4.04E-02 | 6.35E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 218002_s_at | NM_004887 | CXCL14 |

| 4.34E-02 | 1.10E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 201141_at | NM_002510 | GPNMB | -3.98E-02 | 7.19E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 201123_s_at | NM_001970 | EIF5A |

| 4.32E-02 | 2.48E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 215823_x_at | U64661 | LOC341315 | 3.96E-02 | 7.62E-06 | 1.13E-02 | Smoking at TOD | ||

| 4.28E-02 | 4.33E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 221752_at | AL041728 | SSH1 | 3.93E-02 | 2.48E-02 | 9.94E-01 | 215823_x_at | U64661 | LOC341315 |

| Male subjects | Male subjects | ||||||||||

| -5.90E-02 | 1.59E-04 | 4.87E-02 | 201137_s_at | NM_002121 | HLA-DPB1 | 7.25E-02 | 2.42E-10 | 5.40E-06 | Drug use | ||

| -5.81E-02 | 8.14E-02 | 9.87E-01 | 218948_at | AL136679 | QRSL1 | 6.57E-02 | 1.79E-09 | 1.33E-05 | Alcohol use | ||

| -5.36E-02 | 2.46E-02 | 6.09E-01 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 | -6.16E-02 | 3.87E-04 | 8.24E-02 | HSV 1 OD Z-score | ||

| 4.73E-02 | 7.55E-03 | 3.68E-01 | 215009_s_at | U92014 | SEC31A | -5.44E-02 | 2.46E-02 | 6.04E-01 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 |

| 3.97E-02 | 7.06E-02 | 9.39E-01 | 209823_x_at | M17955 | HLA-DQB1 | -4.98E-02 | 8.14E-02 | 9.84E-01 | 218948_at | AL136679 | QRSL1 |

| 3.97E-02 | 3.96E-03 | 2.69E-01 | 220313_at | NM_022049 | GPR88 | 4.71E-02 | 7.55E-03 | 3.64E-01 | 215009_s_at | U92014 | SEC31A |

| 3.90E-02 | 2.96E-02 | 6.65E-01 | 204550_x_at | NM_000561 | GSTM1 | -4.11E-02 | 1.59E-04 | 4.68E-02 | 201137_s_at | NM_002121 | HLA-DPB1 |

| 3.64E-02 | 6.72E-02 | 9.24E-01 | 214877_at | BE794663 | CDKAL1 | 4.03E-02 | 4.45E-04 | 8.62E-02 | Smoking at TOD | ||

| -3.63E-02 | 9.60E-05 | 3.77E-02 | 203851_at | NM_002178 | IGFBP6 | 3.97E-02 | 3.96E-03 | 2.64E-01 | 220313_at | NM_022049 | GPR88 |

| -3.59E-02 | 8.41E-02 | 9.94E-01 | 221875_x_at | AW514210 | HLA-F | 3.67E-02 | 5.43E-02 | 8.51E-01 | 203554_x_at | NM_004219 | PTTG1 |

| 3.58E-02 | 2.52E-02 | 6.15E-01 | 201141_at | NM_002510 | GPNMB | -3.43E-02 | 8.71E-03 | 3.84E-01 | 204670_x_at | NM_002125 | HLA-DRB1 |

| -3.58E-02 | 1.57E-02 | 4.94E-01 | 203031_s_at | NM_000375 | UROS | -3.35E-02 | 8.41E-02 | 9.90E-01 | 221875_x_at | AW514210 | HLA-F |

| -3.56E-02 | 1.26E-02 | 4.60E-01 | 204295_at | NM_003172 | SURF1 | -3.32E-02 | 1.57E-02 | 4.90E-01 | 203031_s_at | NM_000375 | UROS |

| 3.56E-02 | 5.43E-02 | 8.55E-01 | 203554_x_at | NM_004219 | PTTG1 | -3.31E-02 | 9.60E-05 | 3.58E-02 | 203851_at | NM_002178 | IGFBP6 |

| 3.55E-02 | 4.40E-02 | 7.84E-01 | 206339_at | NM_004291 | CARTPT | 3.26E-02 | 4.40E-02 | 7.80E-01 | 206339_at | NM_004291 | CARTPT |

| -3.52E-02 | 9.35E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 208729_x_at | D83043 | HLA-B | 3.25E-02 | 7.06E-02 | 9.36E-01 | 209823_x_at | M17955 | HLA-DQB1 |

| -3.50E-02 | 8.71E-03 | 3.88E-01 | 204670_x_at | NM_002125 | HLA-DRB1 | -3.24E-02 | 9.35E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 208729_x_at | D83043 | HLA-B |

| 3.48E-02 | 6.76E-02 | 9.25E-01 | 221752_at | AL041728 | SSH1 | 3.21E-02 | 6.76E-02 | 9.21E-01 | 221752_at | AL041728 | SSH1 |

| -3.46E-02 | 7.98E-02 | 9.82E-01 | 203374_s_at | AW612376 | TPP2 | 3.16E-02 | 6.18E-02 | 8.93E-01 | 204570_at | NM_001864 | COX7A1 |

| 3.38E-02 | 6.18E-02 | 8.97E-01 | 204570_at | NM_001864 | COX7A1 | 3.09E-02 | 2.96E-02 | 6.61E-01 | 204550_x_at | NM_000561 | GSTM1 |

| Female subjects | Female subjects | ||||||||||

| 2.54E-02 | 1.85E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 219044_at | NM_018271 | THNSL2 | 3.49E-02 | 2.07E-02 | 1.00E+00 | Left brain | ||

| -2.18E-02 | 1.71E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 208691_at | BC001188 | TFRC | 2.44E-02 | 1.85E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 219044_at | NM_018271 | THNSL2 |

| -2.12E-02 | 2.36E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 202747_s_at | NM_004867 | ITM2A | -2.08E-02 | 1.71E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 208691_at | BC001188 | TFRC |

| -2.04E-02 | 1.75E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 200606_at | NM_004415 | DSP | 2.07E-02 | 5.93E-04 | 1.00E+00 | Age | ||

| -2.03E-02 | 2.05E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 204305_at | NM_005932 | MIPEP | -2.03E-02 | 2.36E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 202747_s_at | NM_004867 | ITM2A |

| -2.01E-02 | 6.29E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 207332_s_at | NM_003234 | TFRC | -1.99E-02 | 1.75E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 200606_at | NM_004415 | DSP |

| -1.92E-02 | 5.61E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 202746_at | AL021786 | ITM2A | -1.96E-02 | 2.05E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 204305_at | NM_005932 | MIPEP |

| -1.86E-02 | 2.60E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 220576_at | NM_024989 | PGAP1 | -1.91E-02 | 6.29E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 207332_s_at | NM_003234 | TFRC |

| 1.79E-02 | 1.69E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 209619_at | K01144 | CD74 | -1.82E-02 | 5.61E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 202746_at | AL021786 | ITM2A |

| 1.77E-02 | 1.23E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 220954_s_at | NM_013440 | PILRB | -1.78E-02 | 2.60E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 220576_at | NM_024989 | PGAP1 |

| -1.75E-02 | 1.35E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 201865_x_at | AI432196 | NR3C1 | 1.76E-02 | 1.23E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 220954_s_at | NM_013440 | PILRB |

| -1.73E-02 | 9.17E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 209735_at | AF098951 | ABCG2 | 1.69E-02 | 1.69E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 209619_at | K01144 | CD74 |

| -1.71E-02 | 2.97E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 209314_s_at | AK024258 | HBS1L | 1.68E-02 | 8.54E-02 | 1.00E+00 | Drug use | ||

| -1.71E-02 | 5.99E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 209267_s_at | AB040120 | SLC39A8 | -1.66E-02 | 1.35E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 201865_x_at | AI432196 | NR3C1 |

| -1.70E-02 | 2.88E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 218051_s_at | NM_022908 | NT5DC2 | -1.65E-02 | 9.17E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 209735_at | AF098951 | ABCG2 |

| -1.66E-02 | 1.83E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 213791_at | NM_006211 | PENK | -1.62E-02 | 5.99E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 209267_s_at | AB040120 | SLC39A8 |

| -1.66E-02 | 1.75E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 203697_at | U91903 | FRZB | -1.61E-02 | 1.75E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 203697_at | U91903 | FRZB |

| -1.63E-02 | 9.02E-02 | 1.00E+00 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 | -1.61E-02 | 2.88E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 218051_s_at | NM_022908 | NT5DC2 |

| -1.62E-02 | 2.61E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 217757_at | NM_000014 | A2M | -1.55E-02 | 1.83E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 213791_at | NM_006211 | PENK |

| -1.60E-02 | 6.61E-03 | 1.00E+00 | 211671_s_at | U01351 | NR3C1 | -1.55E-02 | 3.39E-01 | 1.00E+00 | 222274_at | AW975050 | FLJ31568 |

Table 5.

Genes sorted by SVM weight, bipolar versus control

| Expression data only | Demographic, clinical, and expression data | ||||||||||

| All subjects | All subjects | ||||||||||

| SVM-weight | p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol | SVM-weight | p-value | q-value | ID | GenBank | Symbol |

| -1.04E-01 | 4.47E-03 | 9.53E-02 | 205033_s_at | NM_004084 | DEFA1/3 | 2.00E-01 | 2.92E-18 | 4.66E-14 | Drug use | ||

| -1.03E-01 | 1.78E-03 | 6.98E-02 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 | 1.68E-01 | 7.09E-13 | 5.66E-09 | Alcohol use | ||

| -9.48E-02 | 1.34E-02 | 1.46E-01 | 203231_s_at | AW235612 | ATXN1 | -9.09E-02 | 3.22E-04 | 3.62E-02 | 202203_s_at | NM_001144 | AMFR |

| -9.06E-02 | 1.70E-02 | 1.63E-01 | 219525_at | NM_018242 | SLC47A1 | -8.38E-02 | 4.47E-03 | 9.46E-02 | 205033_s_at | NM_004084 | DEFA1/3 |

| 8.92E-02 | 9.79E-03 | 1.27E-01 | 215147_at | AF007147 | CUGBP2 | -7.98E-02 | 1.34E-02 | 1.45E-01 | 203231_s_at | AW235612 | ATXN1 |

| -8.86E-02 | 3.22E-04 | 3.72E-02 | 202203_s_at | NM_001144 | AMFR | 7.67E-02 | 6.28E-05 | 1.96E-02 | PMI | ||

| 7.65E-02 | 2.36E-02 | 1.90E-01 | 204285_s_at | AI857639 | PMAIP1 | 7.63E-02 | 9.79E-03 | 1.27E-01 | 215147_at | AF007147 | CUGBP2 |

| -7.61E-02 | 1.44E-03 | 6.36E-02 | 203031_s_at | NM_000375 | UROS | 6.58E-02 | 2.36E-02 | 1.89E-01 | 204285_s_at | AI857639 | PMAIP1 |

| -7.44E-02 | 6.61E-03 | 1.09E-01 | 218951_s_at | NM_018390 | PLCXD1 | -6.40E-02 | 1.78E-03 | 6.88E-02 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 |

| 7.17E-02 | 6.47E-03 | 1.09E-01 | 215528_at | AL049390 | MGAT5 | -6.23E-02 | 1.70E-02 | 1.62E-01 | 219525_at | NM_018242 | SLC47A1 |

| -6.98E-02 | 1.54E-03 | 6.46E-02 | 221579_s_at | AF062530 | NUDT3 | -5.94E-02 | 1.05E-02 | 1.32E-01 | 209189_at | BC004490 | FOS |

| -6.67E-02 | 1.37E-09 | 2.19E-05 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST | 5.60E-02 | 6.47E-03 | 1.08E-01 | 215528_at | AL049390 | MGAT5 |

| -6.62E-02 | 1.05E-02 | 1.33E-01 | 209189_at | BC004490 | FOS | -5.49E-02 | 6.61E-03 | 1.08E-01 | 218951_s_at | NM_018390 | PLCXD1 |

| -6.48E-02 | 6.72E-06 | 9.04E-03 | 221011_s_at | NM_030915 | LBH | -5.46E-02 | 1.37E-09 | 7.31E-06 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST |

| 6.46E-02 | 4.79E-03 | 9.73E-02 | 217617_at | AW451711 | PBX1 | -5.44E-02 | 2.53E-03 | 7.69E-02 | 203528_at | NM_006378 | SEMA4D |

| -5.98E-02 | 4.63E-03 | 9.59E-02 | 204507_s_at | NM_000945 | PPP3R1 | -5.40E-02 | 1.54E-03 | 6.37E-02 | 221579_s_at | AF062530 | NUDT3 |

| -5.87E-02 | 1.26E-03 | 6.14E-02 | 204545_at | NM_000287 | PEX6 | -5.33E-02 | 2.49E-03 | 7.69E-02 | 200976_s_at | NM_006024 | TAX1BP1 |

| 5.80E-02 | 2.72E-02 | 2.02E-01 | 217482_at | AK021987 | HEMBB1000354 | 5.33E-02 | 4.79E-03 | 9.66E-02 | 217617_at | AW451711 | PBX1 |

| -5.67E-02 | 2.53E-03 | 7.78E-02 | 203528_at | NM_006378 | SEMA4D | -5.23E-02 | 1.26E-03 | 6.05E-02 | 204545_at | NM_000287 | PEX6 |

| 5.45E-02 | 1.45E-02 | 1.52E-01 | 217055_x_at | S83374 | SLC1A2 | 5.17E-02 | 1.45E-02 | 1.52E-01 | 217055_x_at | S83374 | SLC1A2 |

| Male subjects | Male subjects | ||||||||||

| -8.15E-02 | 2.96E-05 | 1.08E-01 | 219525_at | NM_018242 | SLC47A1 | 1.61E-01 | 4.55E-10 | 3.34E-06 | Alcohol use | ||

| -6.62E-02 | 2.50E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 208151_x_at | NM_030881 | DDX17 | 1.27E-01 | 1.68E-12 | 2.47E-08 | Drug use | ||

| -6.36E-02 | 1.02E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 | 7.30E-02 | 3.77E-03 | 3.48E-01 | PMI | ||

| -6.35E-02 | 2.91E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 205048_s_at | NM_003832 | PSPH | -6.30E-02 | 2.96E-05 | 7.68E-02 | 219525_at | NM_018242 | SLC47A1 |

| -6.12E-02 | 2.15E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 218948_at | AL136679 | QRSL1 | -5.73E-02 | 2.91E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 205048_s_at | NM_003832 | PSPH |

| -5.44E-02 | 2.09E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 202203_s_at | NM_001144 | AMFR | -5.47E-02 | 3.85E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 205924_at | BC005035 | RAB3B |

| 5.33E-02 | 4.53E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 216006_at | AF070620 | WIPF2 | -5.16E-02 | 2.50E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 208151_x_at | NM_030881 | DDX17 |

| -5.09E-02 | 3.85E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 205924_at | BC005035 | RAB3B | -5.14E-02 | 2.09E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 202203_s_at | NM_001144 | AMFR |

| -4.90E-02 | 1.17E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 208719_s_at | U59321 | DDX17 | -5.12E-02 | 2.15E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 218948_at | AL136679 | QRSL1 |

| 4.79E-02 | 1.23E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 210738_s_at | AF011390 | SLC4A4 | -4.36E-02 | 1.02E-02 | 3.48E-01 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 |

| 4.79E-02 | 4.39E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 202853_s_at | NM_002958 | RYK | 4.20E-02 | 4.53E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 216006_at | AF070620 | WIPF2 |

| 4.76E-02 | 2.39E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 207181_s_at | NM_001227 | CASP7 | -3.96E-02 | 2.06E-04 | 1.68E-01 | Brain pH | ||

| -4.74E-02 | 2.04E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 204416_x_at | NM_001645 | APOC1 | -3.84E-02 | 1.17E-02 | 3.48E-01 | 208719_s_at | U59321 | DDX17 |

| 4.53E-02 | 1.52E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 204712_at | NM_007191 | WIF1 | 3.76E-02 | 2.06E-02 | 3.48E-01 | 214722_at | AW516297 | NOTCH2NL |

| -4.51E-02 | 3.53E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 204545_at | NM_000287 | PEX6 | 3.75E-02 | 4.39E-02 | 3.48E-01 | 202853_s_at | NM_002958 | RYK |

| -4.50E-02 | 6.16E-03 | 3.49E-01 | 205033_s_at | NM_004084 | DEFA1/3 | 3.74E-02 | 9.42E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 209291_at | AW157094 | ID4 |

| 4.31E-02 | 2.46E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 219255_x_at | NM_018725 | IL17RB | -3.67E-02 | 2.04E-02 | 3.48E-01 | 204416_x_at | NM_001645 | APOC1 |

| -4.29E-02 | 8.23E-05 | 1.34E-01 | 213921_at | NM_001048 | SST | -3.60E-02 | 3.53E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 204545_at | NM_000287 | PEX6 |

| 4.26E-02 | 3.48E-02 | 3.49E-01 | 218500_at | NM_016647 | C8orf55 | 3.56E-02 | 1.23E-02 | 3.48E-01 | 210738_s_at | AF011390 | SLC4A4 |

| -4.25E-02 | 5.38E-07 | 7.90E-03 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 | -3.55E-02 | 6.16E-03 | 3.48E-01 | 205033_s_at | NM_004084 | DEFA1/3 |

| Female subjects | Female subjects | ||||||||||

| 6.17E-02 | 3.51E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 211751_at | BC005949 | PDE4DIP | 9.50E-02 | 3.19E-08 | 3.84E-04 | Drug use | ||

| -5.56E-02 | 3.95E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 | 8.85E-02 | 3.09E-04 | 3.21E-01 | Left brain | ||

| -4.20E-02 | 1.30E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 201222_s_at | AL527365 | RAD23B | 5.17E-02 | 3.51E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 211751_at | BC005949 | PDE4DIP |

| -4.19E-02 | 1.89E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 211990_at | M27487 | HLA-DPA1 | 5.01E-02 | 6.64E-06 | 4.00E-02 | Age | ||

| -4.04E-02 | 1.00E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202581_at | NM_005346 | HSPA1B | -4.93E-02 | 3.95E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202688_at | NM_003810 | TNFSF10 |

| -3.77E-02 | 5.25E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202203_s_at | NM_001144 | AMFR | 4.09E-02 | 2.66E-03 | 3.21E-01 | Alcohol use | ||

| -3.74E-02 | 4.26E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 217757_at | NM_000014 | A2M | -3.88E-02 | 1.30E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 201222_s_at | AL527365 | RAD23B |

| 3.72E-02 | 5.74E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 213757_at | AA393940 | EIF5A | -3.71E-02 | 1.00E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202581_at | NM_005346 | HSPA1B |

| -3.70E-02 | 2.24E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 221579_s_at | AF062530 | NUDT3 | -3.50E-02 | 5.25E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202203_s_at | NM_001144 | AMFR |

| -3.62E-02 | 1.15E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 203416_at | NM_000560 | CD53 | 3.46E-02 | 5.74E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 213757_at | AA393940 | EIF5A |

| -3.49E-02 | 2.55E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 208691_at | BC001188 | TFRC | -3.29E-02 | 4.26E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 217757_at | NM_000014 | A2M |

| 3.36E-02 | 2.92E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 205990_s_at | NM_003392 | WNT5A | -3.26E-02 | 1.15E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 203416_at | NM_000560 | CD53 |

| -3.33E-02 | 2.68E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202291_s_at | NM_000900 | MGP | -3.25E-02 | 1.89E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 211990_at | M27487 | HLA-DPA1 |

| -3.32E-02 | 2.63E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 200800_s_at | NM_005345 | HSPA1A/B | -2.99E-02 | 2.68E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202291_s_at | NM_000900 | MGP |

| -3.30E-02 | 2.60E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 211038_s_at | BC006312 | CROCCL1 | -2.95E-02 | 2.24E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 221579_s_at | AF062530 | NUDT3 |

| -3.27E-02 | 4.16E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 218589_at | NM_005767 | P2RY5 | -2.91E-02 | 2.63E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 200800_s_at | NM_005345 | HSPA1A/B |

| -3.23E-02 | 6.22E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 203231_s_at | AW235612 | ATXN1 | 2.89E-02 | 2.92E-03 | 3.21E-01 | 205990_s_at | NM_003392 | WNT5A |

| -3.21E-02 | 5.41E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 218055_s_at | NM_018268 | WDR41 | -2.89E-02 | 1.45E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 202746_at | AL021786 | ITM2A |

| -3.17E-02 | 3.12E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 210004_at | AF035776 | OLR1 | -2.79E-02 | 5.14E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 209458_x_at | AF105974 | HBA1/2 |

| -3.11E-02 | 1.70E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 206577_at | NM_003381 | VIP | -2.75E-02 | 6.56E-02 | 3.21E-01 | 201718_s_at | BF511685 | EPB41L2 |

Biological relevance

Of the top 20 genes identified using the p-value ranking, 11 have been previously implicated in schizophrenia in at least one study. These genes include: NR4A3 [GenBank:U12767] [16-19], SST [GenBank:NM_001048] [20], NPY [GenBank:NM_000905] [21,22], S100A8 [GenBank:NM_002964] [23], CRH [GenBank:NM_000756] [24,25], GAD1 [GenBank:NM_013445] [26,27], FOS [GenBank:BC004490] [28,29], JUN [GenBank:BG491844] [28,29], DNAJB1 [GenBank:BG537255] [30], SLC16A1 [GenBank:AL162079, GenBank:BF511091] [31], and EGR2 [GenBank:NM_000399] [32,17].

Overlap with the current literature occurs for bipolar disorder as well, although overlap is not as large primarily because of the relative immaturity of the field and concomitant smaller number of literature results. Of the top 20 genes identified using SVM weight or p-value, 7 genes have been implicated previously in bipolar disorder. Interestingly, multiple probes for the same gene are in the top 20 for DUSP6 [GenBank:BC003143, GenBank:BC005047] [33,34] and HLA-DRA [GenBank:M60333, GenBank:M60334] [18]. Single probes previously implicated in bipolar disorder include: SST [GenBank:NM_001048] [20], HLA-A [GenBank:AA573862] [35], NPY [GenBank:NM_000905] [36], HLA-DRB3 [Genbank:NM_002125] [37], and DNAJB1 [GenBank:BG537255] [30].

Interestingly, most of the remaining genes in the list are known to interact with the genes that have a documented association with either bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. These interactions were determined using Ingenuity Systems software. 14 of the 20 genes in the schizophrenia sample are involved in the same biological pathway (Figure 15). By combining the two networks generated by the software package via 3 overlapping genes, 19 of the 20 genes are in a single biological network. Similarly, 13 of the 20 genes are in a single pathway for bipolar disorder (Figure 16). By combining two of the 3 generated pathways through 3 overlapping genes, this biological network represents 16 of the 20 genes on the list.

Figure 15.

Biological network representing the schizophrenia p-value ranking. The network was generated using Ingenuity Systems Pathway analysis. The darker the red the more significant the correlation with the disease.

Figure 16.

Biological network representing the bipolar disorder p-value ranking. The network was generated using Ingenuity Systems Pathway analysis. The darker the red the more significant the correlation with the disease.

One of the more remarkable features of this analysis is the difference in gene expression patterns between males and females. Much speculation has surrounded the role of gender in psychiatric disorders based on morphological and clinical comparisons between affected males and affected females. This analysis may provide further evidence to support and broaden this hypothesis. The most prevalent gender-based differences associated with mental disorders are in the structural abnormalities that have long been known in schizophrenia [38]. These have been validated using CT and MRI scans, demonstrating differences in ventricle size in males and females with schizophrenia; specifically the left ventricles of males are known to be enlarged relative to both their healthy counterparts and affected females [39-45]. Another structure showing a difference in affected males and females is the corpus calosum [46-48]. The temporal lobe appears smaller in affected men than women [49]. Specifically, the superior temporal gyri [50], the posterior superior temporal gyrus [51], and Herschel's gyri [51] have all been shown in one or more studies to be reduced in affected males when compared to their unaffected male counterparts or affected females. Volume reductions have also been observed in the amygdale-hipocampal complex [52]. Reduced asymmetry of the planum temporale has been observed in females in both MRI and post mortem studies [53-56]. In this study we provide additional evidence to further bolster the claim of gender differences, but this new evidence is in the form of molecular differences between affected males and females in both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This may all provide evidence that gender may have confounded the results of past molecular analyses into these disorders.

The ranking based on the SVM weights does not produce a significant number of genes previously implicated in schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. This does not necessarily mean this measure does not provide as much biological insight as the ranking based on p-value. The smaller overlap may instead be because the SVM-based method is more different from previous studies than is the method based on p-values. Whereas previous studies sought individual genes, much as the ranking by p-value does, the ranking by SVM weight seeks genes that are predictive in the context of other genes. Therefore it seems likely that this more global look at bipolar disorder and schizophrenia is producing genes missed in previous analyses of microarray data on brain tissue.

Impact of alcohol and drug use

Consider the schizophrenia versus control classification task. Feature rankings by p-value, such as Table 2, may include alcohol use (AU) and drug use (DU) associated genes, and some of these may not be associated to schizophrenia. AU and DU are known to alter gene expression, that is, there are genes that are differently expressed in heavy AU/DU subjects and in low AU/DU subjects. Such AU/DU associated genes will also be differently expressed in the schizophrenia and control classes, simply because there are more high AU/DU subjects in the schizophrenia class, and more low AU/DU subjects in the control class (Table 1). Therefore, AU/DU associated genes may appear in the feature rankings (Table 2).

Identical reasoning applies to the bipolar disorder versus control task, which exhibits a similar difference in AU/DU distribution between the two classes. This should be kept in mind when analyzing the rankings. Note that these differences in distribution are already present in the population and therefore difficult to avoid in the samples.

Post-stratification can potentially be used to remove the confounding effects of variables such as AU and DU. Essentially, post-stratification computes a subset of the data such that the subset's AU/DU distribution is identical in each class. We have applied post-stratification. A detailed description of the method that we used together with its results is available in additional files 1 and 2. In these results however, post-stratification proved ineffective because it significantly reduced the amount of data, and therefore also the power of the statistical methods, resulting in unacceptably high false discovery rates. We briefly quantify this in the following paragraph.

Consider the p-value ranking for the schizophrenia versus control task, expression data only, all subjects (Table 2). Reporting all top 20 features as being significant results in a false discovery rate of 3.8%, that is, fewer than one feature is a false discovery. However, if we compute a similar ranking on the stratified data, which contains only 121 of the 332 samples in the original data , then reporting only the four top-ranked features as significant already yields a false discovery rate of 62.8%, that is, more than two of these four may be false discoveries. Because of this high false discovery rate, we decided not to use stratification in the paper and to accept the possibility of AU/DU associated genes in the rankings. Further analysis, possibly using more data, is required to identify such genes.

Note that this problem is partially mitigated by use of the SVM-based ranking instead, when using demographic features in addition to gene expression. If a gene's correlation with disease is only because of its correlations with AU/DU, then the SVM will prefer to place most/all of the weight on AU and DU rather than on this gene. The gene will receive high weight only if it provides additional predictive ability for disease beyond its association with AU/DU. As a result, the ranking will mostly include genes that are truly associated to the disease, which may explain the difference between the SVM and p-value rankings. The extent of this mitigation requires further study to quantify, which is difficult because we do not have a ground truth to compare to, that is, it would require that we know which genes are directly associated with AU/DU and are not associated with the diseases.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates that both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia induce substantial changes in gene expression within the brain – substantial enough that each can be distinguished from normal control with an area under the ROC curve of over 0.9. The paper also demonstrates the utility of combining gene expression and clinical data. To our knowledge, this is the first time such a combination has been employed on this scale. Finally, the paper demonstrates the significant advantage of support vector machines for this task over other widely used algorithms from statistical classification and machine learning.

Using these classification schemes we have shown an overlap with the current literature when ranking the genes according to p-value. In fact, nearly the entire schizophrenia and the entire bipolar disorder list are either indicated in the literature or are involved in a biological network with a previously implicated gene. However, when ranking the genes based on SVM weight only 1 or 2 genes out of 20 on each list overlapped with the current literature. This does not necessarily imply that these methods are not viable but rather that these may be previously unidentified candidates that have risen to the top due to the large sample size of this analysis and the application of alternative classification algorithms for microarray data analysis.

This paper also discussed the possible impact of variables such as alcohol and drug use on the presented gene rankings. Post-stratification can correct for such variables, but it significantly reduces the power of the statistical methods. Therefore, data for more controls with high values for these variables is required so that the AU/DU distributions in the different classes become more similar. It should also be kept in mind that this is a retrospective study on a given data set and that all results will require further clinical validation. Samples in the collection were matched during the collection process for as many parameters as possible. While there may be some confounding effects from pre-mortem consumption of alcohol and other non-prescription medication, this analysis is our best attempt to account for differences in the factors through analytical means (Torrey, Webster, et al 2000). Since, these samples are not derived from controlled animals models we will have to rely on these analytical means to aid our efforts in dissecting the root causes of complex diseases.

Methods

Encoding of nominal features

Because most classification techniques that we consider are restricted to numerical features only, we re-encode each nominal feature as a numeric feature. Table 1 indicates the encoding after each feature value. For the binary features "Sex", "Left brain", "Brain region", and "Smoking at time of death", we use an encoding with three values: 1, 0, and -1, with 0 indicating "unknown". The features that have essentially ordered values, such as "Alcohol use", "Drug use" and "Rate of death", we encode with a simple integer encoding.

Software packages and versions

We choose the SVM-light software version 6.01 [57] for constructing linear soft margin SVMs. We use the NSC software PAM version 1.28, which is available at: http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/PAM/. We use the reimplementation of C4.5 that is available in the Weka data mining tool version 3.4.4 [58]. We also use Weka 3.4.4's implementations of NB and kNN. We use the EOV software version 1.0 by Hardin et al. [9]. To compute the q-values, we use the software QVALUE version 1.1 developed by Storey [15]. All are freely available.

ROC curves and AUC

Most classifiers provide confidence scores for their predictions. The classification behavior of such classifiers can be modified by applying a threshold to this score: only predict positive if the confidence is above the given threshold. By varying the threshold, we obtain different ROC points, which can be connected into a curve. (The curve can then be used, for example, to select an appropriate threshold.) We present such a curve for each classifier and report the corresponding AUC.

To obtain the ROC curves, we use 10-fold cross-validation (CV). 10-fold CV is often used to evaluate the predictive performance of classifiers if the number of instances is small. In this situation, 10-fold CV results in a lower-variance estimate of error than does the use of a single held-aside test set. 10-fold CV consists of three steps: (a) partition the data set D into 10 subsets Ti; (b) train 10 classifiers on the training sets D-Ti; (c) test classifier i on test set Ti. We pool the predicted confidence values of the classifiers over the 10 test sets to construct the ROC curve. The CV algorithm that we employ is stratified, which means that it ensures that the Ti have identical class distributions, or as nearly identical as possible.

To assess statistical significance when comparing two classification techniques by AUC value, we use a two-sided paired t-test. The paired sample values used in the test are the AUC values computed for the two techniques on the 10 CV test sets.

Algorithm parameters

Most classification techniques come with a number of parameters. We set all parameters to their default values, except for the following. The parameter C of SVM-light, which controls the contribution of the misclassified examples, is set to 1.0 (SVM-light is not particularly sensitive to C's value). We enable Laplace smoothing of DT's confidence values. Following Hardin et al. [9], we set EOV's number of decision stumps N to 20. We enable Weka's discretization feature for NB. We run kNN with k = 3 neighbors.

We tune NSC's Δ parameter, which controls the amount of shrinkage, by means of 10-fold CV, as suggested by Tibshirani et al. [7]. Recall that we also create ROC curves by means of CV. To avoid overfitting the test set, we repeat the parameter tuning each time we run NSC, that is, for each ROC CV fold. The tuning selects the value of Δ that maximizes TP + TN, with TP the true positive rate and TN the proportion of negative examples that are correctly classified.

The performance of some classification techniques can be improved by running a feature selection method prior to constructing the classifier. We implement feature selection for SVM, NB, and 3NN. The feature selection works as follows. We perform a two-sided paired t-test for each feature comparing its value in the two classes. Then we rank the features by their t-test's p-value and retain the 10% features that most significantly differ in the two classes (similar to the p-value ranking discussed before). We repeat the feature selection for each CV fold and perform the t-test on the corresponding training set.

To compute the feature ranking by SVM weight, we normalize each feature by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation (in the data set at hand), and run the SVM algorithm on the transformed data. The rationale behind this is to avoid favoring features with a small value range in the ranking. We also enable feature selection to construct the ranking by SVM weight as discussed before.

Authors' contributions

JS performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. SD provided the data, provided critical input and drafted the biological relevance section of the manuscript. DP supervised the study and helped drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Description of additional data files

• FeatureRankingsStratified.{doc, pdf} (Microsoft Word and PDF format): "Feature rankings on post-stratified data" in additional files 1 and 2.

Feature rankings similar to Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 computed for a post-stratified copy of the data set. See Section "Impact of alcohol and drug use" for more information.

• FeatureRankingsDetailed.xls (Microsoft Excel format): "Feature rankings with additional information" in additional file 3.

Feature rankings that contain the same information as Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, but also include additional information, such as gene title and chromosome location.

Supplementary Material

Feature rankings on post-stratified data

Feature rankings on post-stratified data

Feature rankings with additional information

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Research supported by the US NSF grant IIS 0534908 and the US NIH grant R01 CA127379. Postmortem brain tissue was donated by The Stanley Medical Research Institute's brain collection. JS is a post-doctoral fellow of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen). DP is supported by the US NSF grant IIS 0534908.

Contributor Information

Jan Struyf, Email: jan.struyf@cs.kuleuven.be.

Seth Dobrin, Email: seth.dobrin@monsanto.com.

David Page, Email: page@biostat.wisc.edu.

References

- The Stanley Neuropathology Consortium http://www.stanleygenomics.org

- Torrey EF, Webster MJ, Knable MB, Johnston N, Yolken RH. The Stanley Foundation brain collection and Neuropathology Consortium. Schizophr Res. 2000;44:151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Irizarry RA. Stochastic models inspired by hybridization theory for short oligonucleotide arrays. J Comput Biol. 2005;12:882–893. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2005.12.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik V. Wiley Series on Adaptive and Learning Systems for Signal Processing, Communications, and Control. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. Statistical Learning Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Furey TS, Cristianini N, Duffy N, Bednarski DW, Schummer M, Haussler D. Support vector machine classification and validation of cancer tissue samples using microarray expression data. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:906–914. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20:273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Narasimhan B, Chu G. Diagnosis of multiple cancer types by shrunken centroids of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6567–6572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082099299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan JR. Morgan Kaufmann Series in Machine Learning. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. C4.5: Programs for Machine Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J, Waddell M, Page CD, Zhan F, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy J, Crowley JJ. Evaluation of multiple models to distinguish closely related forms of disease using DNA microarray data: an application to multiple myeloma. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingos P, Pazzani MJ. On the optimality of the simple Bayesian classifier under zero-one loss. Mach Learn. 1997;29:103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Aha DW, Kibler DF, Albert MK. Instance-based learning algorithms. Mach Learn. 1991;6:37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Provost FJ, Fawcett T. Analysis and visualization of classifier performance: comparison under imprecise class and cost distributions. In: Heckerman D, Mannila H, Pregibon D, editor. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining: 14–17 August 1997; Newport Beach. Menlo Park, CA: AAAI Press; 1997. pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Joachims T. Text categorization with suport vector machines: learning with many relevant features. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 1998;1398:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J Roy Stat Soc B. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme C, Filion C, Labelle Y. Functional characterization of SIX3 homeodomain mutations in holoprosencephaly: interaction with the nuclear receptor NR4A3/NOR1. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:502–508. doi: 10.1002/humu.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CD, Sanders-Bush E. A single dose of lysergic acid diethylamide influences gene expression patterns within the mammalian brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:634–642. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansa KD, Muscat GE. TRAP220 is modulated by the antineoplastic agent 6-Mercaptopurine, and mediates the activation of the NR4A subgroup of nuclear receptors. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;34:835–848. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]