Abstract

In rats, expression of the immediate early gene, c-fos observed in the brain following male copulatory behavior relates mostly to the detection of olfactory information originating from the female and to somatosensory feedback from the penis. However, quail, like most birds, are generally considered to have a relatively poorly developed sense of smell. Furthermore, quail have no intromittent organ (e.g., penis). It is therefore intriguing that expression of male copulatory behavior induces in quail and rats a similar pattern of c-fos expression in the medial preoptic area (mPOA), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTM) and parts of the amygdala. We analyzed here by immunocytochemistry Fos expression in the mPOA/BSTM/amygdala of male quail that had been allowed to copulate with a female during standardized tests. Before these tests, some of the males had either their nostrils plugged, or their cloacal area anesthetized, or both. A control group was not exposed to females. These manipulations did not affect frequencies of male sexual behavior and all birds exposed to a female copulated normally. In the mPOA, the increased Fos expression induced by copulation was not affected by the cloacal gland anesthesia but was markedly reduced in subjects deprived of olfactory input. Both manipulations affected copulation-induced Fos expression in the BSTM. No change in Fos expression was observed in the amygdala. Thus immediate early gene expression in the mPOA and BSTM of quail is modulated at least in part by olfactory cues and/or somatosensory stimuli originating from the cloacal gland. Future work should specify the nature of these stimuli and their function in the expression of avian male sexual behavior.

Keywords: Immediate early gene, Medial preoptic area, Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, Copulatory behavior, Olfaction, Cloacal gland, Anesthesia

1. Introduction

Immunocytochemical visualization of the nuclear protein products of immediate-early gene (IEGs), such as c-fos, has been used extensively to delineate neural circuits involved in the expression of sexual behavior across a large number of species [65, 85]. Previous work in quail and in various mammalian species has identified the medial preoptic area (mPOA), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTM) and parts of the amygdala as reliable sites of c-fos induction in subjects engaging in male-typical sexual behaviors [18, 24, 27, 58, 65, 76, 82, 85]. C-fos induction can be related to neural activity induced by sensory stimulation and/or to motor outputs during sexual behavior [65].

The similarity in IEG expression following the occurrence of male sexual behavior in birds [58, 82] and mammals (see reviews cited above) is quite interesting given the important differences in sensory stimuli and effector organs implicated in this behavior. Somatosensory feedback from the penis and olfactory/vomeronasal inputs from the female play a central role in the c-fos activation observed after performance of male sexual behavior in rats [18]. In birds, it is generally thought that olfactory cues have relatively little or even no importance in the control of social behavior, although a few studies indicate that olfactory cues originating in the female could modulate aspects of the reproductive behavior as demonstrated in ducks [13] and auklets [44]. In contrast, visual and acoustic cues appear to be of primary importance in the control of socio-sexual interactions and seem to be sufficient to elicit copulatory responses [34]. Moreover, most bird species do not possess an intromittent organ (e.g., penis) so that the expression of copulatory behavior is likely to be affected by tactile stimuli from the genital area in a manner that is quite different from what is observed in mammals [10]. The fact that quail display a pattern of Fos activation in the brain and in the mPOA in particular that is very similar to what is observed in mammals may, however, be taken as evidence that they are more affected by olfactory stimuli than generally thought and/or that they are very sensitive to tactile inputs from the genital area, despite the absence of a penis. Because the neural mechanisms underlying the processing during male sexual behavior of olfactory cues and somatosensory inputs originating from the cloacal region have not been investigated in birds, this hypothesis is currently difficult to evaluate. In the present experiment, we tested whether these inputs play a role in the c-fos induction previously observed in areas of the quail brain directly related to male sexual behavior. Specifically, we investigated by immunocytochemistry whether the Fos protein expressed following copulation in the mPOA/BSTM/amygdala of male quail is affected if subjects are exposed to the female after having their nostrils plugged with dental cement and/or their cloacal area anesthetized by a xylocaine spray. We also investigated in parallel whether these manipulations affect the expression of male copulatory behavior.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

This study was performed on male Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) that were purchased at 4 weeks of age from a local breeder in Belgium (Degros Farms, Rechrival). Throughout their life at the breeding colony and in the laboratory, birds were maintained on a photoperiod simulating long summer days (16L:8D). All birds were isolated in individual cages before the start of the experiment. Food and water were available ad libitum. All experimental procedures were in agreement with the Belgian laws on the “Protection and Welfare of Animals” and on the “Protection of Experimental Animals” and the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research involving Animals published by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals at the University of Liège.

2.2. Surgical procedures and hormonal treatments

One day after their arrival in the laboratory, all males were castrated under complete anesthesia (Hypnodil™, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium, 15 mg/kg) using procedures that were previously described [80]. Four weeks later, all birds were implanted under the skin in the neck region with one 20 mm long Silastic™ implant (Silclear™ Tubing, Degania Silicone Ltd., Degania Bet, 15130, Israel; 1.57 mm i.d.; 2.41 mm o.d.) filled with crystalline testosterone. These implants restore in castrated male quail physiological levels of the steroid that are typical of sexually mature males and produce a full activation of male sexual behavior [14]. The cloacal gland, an androgen-dependent structure [78], was measured periodically with callipers (greatest width × greatest length in mm2 = cloacal gland area, CGA) to confirm the effectiveness of the testosterone treatment. The body mass was also recorded at the same time.

2.3. Male sexual behavior

To assess copulatory behavior, the experimental bird was introduced into a test arena (60 ×40 ×50 cm) that contained a sexually mature female with which the male could freely interact. The latency and frequency of the following male sexual behavior patterns were then recorded during a 5 min period: neck grabs (NG), mount attempts (MA), mounts (M) and cloacal contact movements (CCM) [2, 48].

2.4. Experimental procedures

2.4.1. General procedures

Two weeks after implantation of the testosterone-filled Silastic™ capsules, all subjects were pre-tested for the occurrence of male-typical copulatory behavior during five separate 5-min periods of interactions with a sexually mature female (see detailed procedure above) in order to confirm the hormonal state of the animals and the efficacy of the testosterone replacement therapy. Only subjects that displayed active copulatory behavior entered the next phase of the experiment. On the basis of results obtained during these preliminary tests, birds (n=35) were randomly assigned to one of five groups that were matched based on the mean frequency (during 5 tests) of the copulatory behavior patterns (NG, MA, M, CCM), on the size of the cloacal gland (CGA) and on the body mass (BM). One way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were then used to confirm that these groups did not differ significantly for any of these measures (NG : F4,31 = 0.199, p = 0.9370; MA : F4,31 = 0.215, p = 0.9281; M : F4,31 = 0.350, p = 0.8418; CCM : F4,31 = 0.064, p = 0.9921; CGA: F4,31 = 0.608, p = 0.6597; BM: F4,31 = 0.230, p = 0.9197).

2.4.2. Nostrils occlusion and behavioral confirmation of anosmia

All subjects were lightly anaesthetized (Hypnodil, 5mg/kg) and were made anosmic by a complete blockade of the 2 external nares with a layer of rapid-drying dental cement. Males exposed to control treatments were also treated with cement that was applied to the base of the beak, avoiding contact with the nares. Subjects were observed closely both during and after recovery from the anesthesia for signs of respiratory distress. The presence of the cement, the subject’s general state and their ability to feed were verified each day until brain collection.

Assessment of odor perception was conducted 2 days after cement application. To verify whether blocking the external nares with dental cement indeed impaired odor perception, the subject’s responsiveness to a volatile odorant was assessed using procedures similar to those described by Porter et al. [67]. Acetic acid was selected as the olfactory stimulus to test olfactory function because it elicited strong behavioral responses in quail. Water was used as an odorless control.

The subject was held loosely by hand, under a lamp. When the subject became immobile, a soft plastic squeeze pipette containing a few drops of acetic acid or water was held with its open tip 3–4 mm from the subject’s nares and was gently squeezed 3 times next to each nostril alternatively. The subject’s response during odor exposure was given a single qualitative score for each test on the following scale: 0 = no observable response; 1 = slight movement of the head, beak clapping; 2 = abrupt shaking or jerking of the head, beak clapping and pecking toward the pipette. Each subject was tested successively in a random order with the 2 stimuli (acetic acid and water) and the average of the three reactions to a same stimulus was used in all subsequent analyses.

2.4.3. Cloacal gland anesthesia and behavioral confirmation of anesthesia

Ten additional male quail that were not included in the main experiment were used to evaluate the cloacal gland sensitivity to xylocaine and the duration of the xylocaine-induced anesthesia to provide baseline information in order to decide on the protocol for the final test. The cloacal gland sensitivity was assessed with a Semmes-Weinstein aesthesiometer (Semmes-Weinstein Monofilaments, Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) that is made of a series of 20 plastic monofilaments, each fixed on a plastic handle. All filaments have the same length (37 mm) but their diameters increases linearly from 0.064 to 1.143 mm. This diameter is linearly related to the logarithm of the force measured when pressing the tip of each monofilament against a scale (force increases logarithmically from 0.005 to 446.6 g, and Log10 of (10× force in mg) increases linearly from 1.65 to 6.65). The aesthesiometer was used as described by Evrard and Balthazart [38].

The cloacal gland of the subject was given 7–8 sprays of xylocaine 10% (n=5; Astra Zeneca) or its vehicle as a control (n= 5). The subject was gently held in one hand and with the other hand, the tip of a monofilament was pressed until the monofilament bent successively on the center of the cloacal gland and subsequently on the right pelvic apterium (naturally bare surface not covered with feathers) covering the ilium region as a control zone. This application was quickly repeated 3 times and the experimenter observed whether the constant bending force applied onto the skin was able to induce a reaction. Stimulation of the cloacal gland with adequate filaments induced a slight and short ruffling of the cloacal gland feathers probably due to a reflex activation of the underlying smooth cutaneous muscles [38]. In contrast, the stimulation of the ilium activated the striated muscles of the right leg. After an interval of 10 sec, the next (more rigid) monofilament was similarly applied. Tests were continued until 2 successive monofilaments had evoked a response of the subject. A subject was considered as non-responding if the application of the thickest monofilament (1.143 mm) failed to elicit a reaction.

Responsiveness of the cloacal gland and ilium were tested 5, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min after xylocaine (or vehicle) application in order to evaluate the duration of anesthesia. One week later, subjects were tested in the same way with the reversed treatment (xylocaine vs. vehicle) so that all 10 birds had been tested in both conditions and could be used as their own control.

2.4.4. Final 10 min sexual behavior test

One week after the cement application, birds were subjected to a 10 min behavioral test during which they had the opportunity to interact freely and express sexual behavior with a sexually mature female under one of the following conditions: (1) males made anosmic by placement of nasal plugs (dental cement blocking both nostrils – SEX/ANOSMIA group); (2) males sprayed with xylocaine on the cloacal gland 5 min before testing (SEX/ANESTHESIA group); (3) males simultaneously exposed to both manipulations (anosmia and cloacal gland anesthesia; SEX/BOTH group); (4) males exposed to control treatments (dental cement on the beak next to the nostrils and spray with water on the cloacal gland; SEX group; positive control). A 5th group of birds received both control treatments and were only handled and replaced in their home cage without being presented with a female (CTRL group; negative control). At the end of the test, birds were replaced in their home cage until sacrifice, 90 min after the start of behavioral manipulations.

2.4.5. Fos Immunocytochemistry

Ninety minutes following the end of the behavioral test, subjects were decapitated and their brain quickly dissected out of the skull. At that time, the completeness of castration and the presence of Silastic™ implants were checked. All birds were found to be completely castrated and they all still possessed their testosterone implant. Brains were then placed into acrolein fixative (5% in phosphate buffer 0.1 M-saline 0.9%, pH 7.2) for 2.5 hours, washed twice in PBS (30 min) and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for 24 h at 4 °C. The brains were then frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until used.

The forebrain of each subject (from the level of the tractus septopallio-mesencephalicus (TSM) to the caudal end of the brain) was cut in the coronal plane with a cryostat at −20°C in 4 series of 30 µm thick sections. One series of sections (120 µm between two successive sections) was stained by immunocytochemistry for the protein product of the c-fos gene (Fos) with a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against an avian Fos protein sequence [39] prepared and validated by D’Hondt and colleagues [28]. Immunocytochemical labeling was carried out by the avidin-biotin technique on free-floating sections as previously described [82]. Briefly, sections were incubated sequentially in 0.6% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min to block endogenous peroxidases, followed by 5% normal goat serum for 30 min to decrease non specific binding. Sections were then left overnight at 4°C in the primary antibody diluted 1:8000. Sections were then incubated with a goat anti-rabbit biotinylated antibody (Dako Cytomation, Denmark; 1:400 in TBST) for 2 hours. The antibody-antigen complex was localized by the avidin-biotin complex method performed with a Vector Elite Kit (Kit ABC Vectastain Elite PK-6100, Vector Laboratories PLC, Cambridge, UK). All reagents were in 0.01 M PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and several rinses were performed between each step. Finally, the peroxidase was visualized with diaminobenzidine (3,3’diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride) as chromogen. Sections were mounted on microscope slides in a gelatin-based medium and coverslipped.

The olfactory bulbs were separately sectioned in 4 series of 16 µm thick sections that were mounted directly on gelatin-coated slides. These slides were stained for Fos as mounted sections as described above and also with a rabbit antibody raised against the immediate early gene zenk also known as egr-1 in mammals (Santa Cruz Biotech, Inc., CA, USA, 1:1000). Binding of this antibody was revealed by the same method as for Fos (biotinylated goat anti-rabbit followed by avidin-biotin complex method and diaminobenzidine).

2.5. Data analysis

The numbers of Fos-ir cells were counted in brain areas previously implicated in the expression of male quail sexual behavior [7, 24, 58, 82, 83] and in brain areas potentially implicated in the avian olfactory pathway [20, 40, 72, 74]. The number Fos-ir cells present in various brain regions was quantified by the experimenter (MT) who was blind to the experimental treatment of the birds using computer-assisted image analysis. Sections were digitized through a video camera attached to the microscope (20 × objective) and Fos-ir cells were counted with a Macintosh-based image analysis system using the particle counting protocol of the NIH Image program (Version 1.62; Wayne Rasband, NIH, Bethesda, MD USA). Digital images were made binary and manual threshold was used for discriminating the labeled material from the background. Exclusion thresholds were set at 20 (low threshold) and 200 (high threshold) pixels to remove from the counts dark objects that did not have the size of a cell nucleus.

Fos expression was quantified in a total of 14 different brain areas that are schematically illustrated in Figure 1. In each area (except for the CPi, see below), the numbers of Fos-ir cells were measured in one entire field (computer screen; length: 0.536 mm; height: 0.360 mm; field always placed in landscape position unless otherwise stated) that was placed in a standardized manner based on predefined anatomical landmarks in the sections (e.g., edge of ventricles or prominent fiber tracts). For each area (except for the CPi), the number of Fos-ir cells were counted in both the left and right side of the section and were summed. Brain structures were identified based on the atlas of the quail and chicken brain [19, 54] but the nomenclature used in the present paper follows the recently revised nomenclature for the avian brain [73].

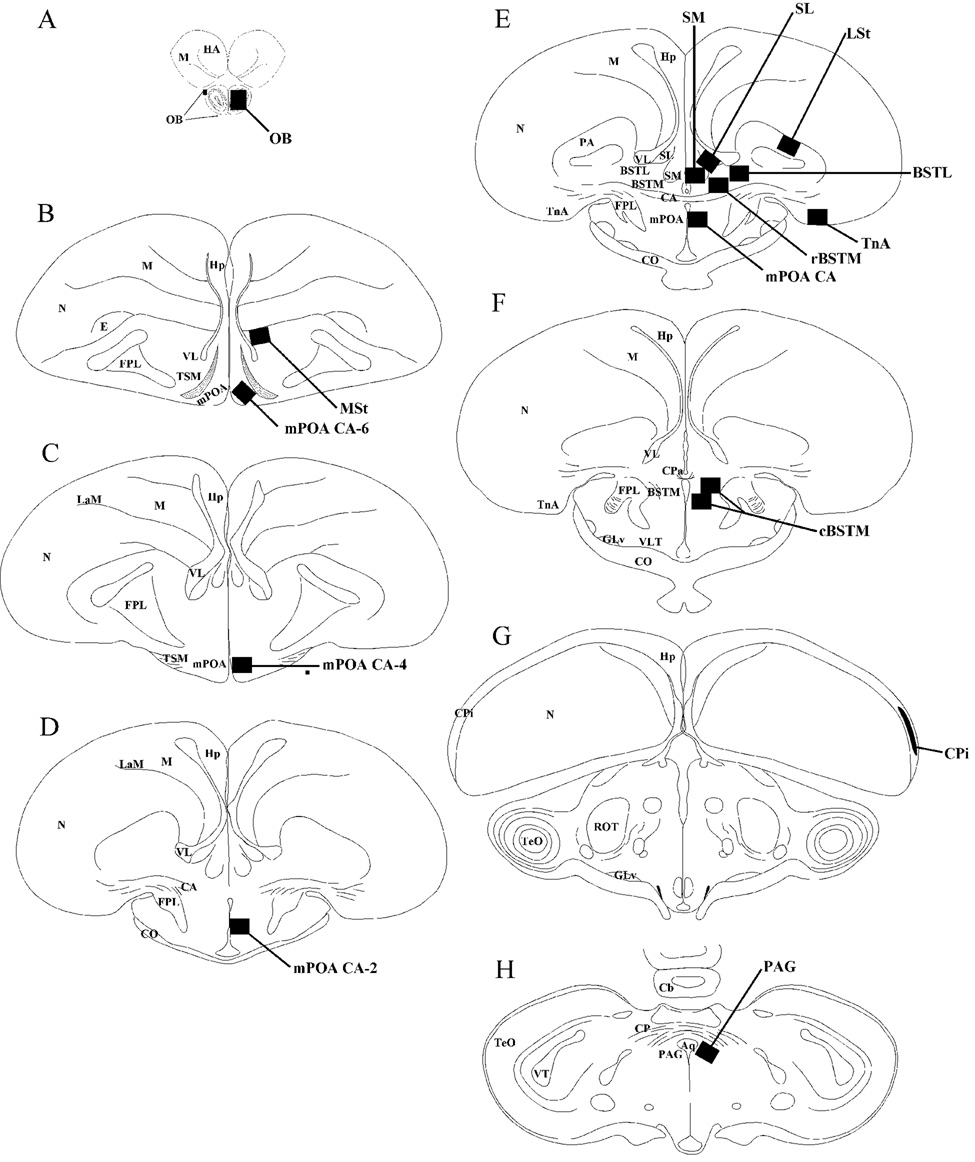

Figure 1.

Schematic drawings of coronal sections through the quail brain illustrating the areas where Fos expression was quantified (dark areas). Panels A through H represent coronal sections through the quail brain presented in a rostral to caudal order. Aq, aqueduct mesencephalii; BSTL, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, lateral part; BSTM, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, medial part; CA, commissura anterior; Cb, cerebellum; CO, chiasma opticum; CP, commissura posterior; CPa, commissura pallii; CPi, piriform cortex; E, entopallium; FPL, fasciculus prosencephali lateralis; GLv, nucleus geniculatus lateralis, pars ventralis; HA, hyperpallium apicale; Hp, hippocampus; LaM, mesopallial lamina; LMD, lamina medullaris dorsalis; LSt, lateral striatum; mPOA, medial preoptic area; M, mesopallium; MSt, medial striatum; N, nidopallium; OB, olfactory bulb; PAG, periaqueductal gray ; SL, lateral septal nucleus; SM, medial septal nucleus; TnA, nucleus taeniae of the amygdala; TeO, tectum opticum; TSM, septopallio mesencephalic tract; VL, lateral ventricle; VLT, nucleus ventrolateralis thalami; VT, ventriculus tecti mesencephali.

Fos-ir cells were quantified in following areas

Areas related to sexual behavior

Medial Preoptic Area (mPOA)

Fos-ir cells were counted at 4 different rostro-caudal levels within the mPOA in sections that were approximatively 240 µm apart. These levels were aligned based on the position where the anterior commissure (CA) reaches its largest extension (corresponding approximately to plate A8.2 in the chicken atlas; see [54]. Fos-ir cells were counted in this section corresponding to the most caudal part of the mPOA (mPOA CA) and in three additional sections located 240 (mPOA CA-2), 480 (mPOA CA-4) and 720 (mPOA CA-6) µm more rostrally. In section mPOA CA, the quantification field was first located in the corner formed by the ventral edge of the anterior commissure and the lateral edge of the third ventricle. The computer field was then moved the height of one field ventrally (0.360 mm) along the third ventricle and quantification was carried out at this location (see Figure 1E). In the mPOA CA-2 that corresponds to the section where the anterior commissure only begins to appear, the quantification field was first placed in the corner formed by the lateral edge of the third ventricle and the floor of the brain. The computer field was then moved the height of one field dorsally (0.360 mm) along the third ventricle and quantification was carried out at this location (see Figure 1D). In mPOA CA-4, a level where the lateral edge of the TSM is just below the fasciculus prosencephali lateralis (FPL), the quantification area was first delimited by the floor of the brain and the edge of the third ventricle. The computer field was then moved a half field dorsally (0.180 mm) along the inter-hemispheric fissure and quantification was carried out at this location (see Figure 1C). Finally, in the most rostral level analyzed (mPOA CA-6), where the TSM assumes an inverted "V" shape (see Figure 1B), the quantification area was delimited by the bending of the TSM and the floor of the brain section and the lateral edge of the inter-hemispheric fissure. The entire computer field was always quantified (0.193 mm2).

Medial part of the Bed nucleus of the Stria Terminalis (BSTM)

Fos induction was quantified in 2 different parts of the BSTM. In the rostral BSTM (rBSTM), located dorsally to the caudal edge of the anterior commissure, the quantification field (0.193 mm2) was initially aligned with the dorsal edge of the commissure and the lateral edge of the inter-hemispheric fissure. The field was then moved laterally by one field length (0.536 mm), in a direction parallel to the dorsal edge of the anterior commissure and quantification was done at this location (see Figure 1E). In a section located 240 µm more caudally corresponding to the caudal BSTM (cBSTM), two quantification fields (0.386 mm2) were summed to cover the nucleus where it assumes a characteristic 'V' shape (see Figure 1F; see definition of this nucleus by [5]. The first quantification field was initially positioned in the same manner as for the caudal mPOA (i.e. adjacent to the third ventricle and at the same dorso-ventral level); the computer field was then moved one field ventrally (0.536 mm) and quantification was carried out at this location in the entire computer field (0.193 mm2). Then, the same computer field was moved one height (0.360 mm) dorsally along the third ventricle and one half field laterally. Quantification was performed at this level in the entire computer field (0.193 mm2). Data from the two quantification fields were averaged before any further analysis.

Lateral part of the Bed nucleus of the Stria Terminalis (BSTL)

The BSLT (formerly known as nucleus accumbens in Kuenzel and Masson, 1988) was analyzed in the same section as the most caudal section of the mPOA (see Figure 1E). The left corner of the quantification field was positioned directly underneath the tip of the lateral ventricle and quantification was performed at this level (0.193 mm2).

Lateral Septal nucleus (SL)

The quantification field was precisely placed in order to cover entirely the bulge of the lateral septal nucleus into the lateral ventricle (see Figure 1E), at the level where the anterior commissure reaches its largest extension (same level as mPOA CA).

Nucleus taeniae of the amygdala (TnA)

Fos induction in the TnA was quantified in the section also containing the LS and mPOA-CA (see Figure 1E). The quantification field was aligned with the ventral surface of the brain and delimited dorsally by the lateral ramification of the anterior commissure.

Periaqueductal gray (PAG; known as Substantia grisea centralis in birds)

Fos-ir cells in the PAG were quantified in the section corresponding approximately to plate A4.8 in the chicken brain atlas [54] where the posterior commissure reaches its largest medio-lateral extension. The surface analyzed (0.193 mm2) was delimited by the corner formed by the ventral edge of the posterior commissure (CP) and the lateral edge of the third ventricle (see Figure 1H).

Areas potentially related to olfaction

Medial Septal nucleus (SM)

The quantification field for the SM was first localized in the corner formed by the dorsal edge of the anterior commissure and the lateral edge of the interhemispheric fissure. The computer field was then moved the height of one field dorsally (0.360 mm) along the interhemispheric fissure and quantification was carried out at this location (see Figure 1E).

Medial striatum (MSt)

Formerly known as the paraolfactory lobe in Kuenzel and Masson (1988), the MSt was analyzed in the same section as the mPOA CA-6 (see Figure 1B). The quantification field was precisely positioned in the corner formed by the ventral edge of the lamina medullaris dorsalis and the lateral ventricle.

Lateral striatum (LSt; formerly known as Paleostriatum augmentatum)

The LSt was analyzed in the same section as the mPOA-CA (see Figure 1E). The quantification field was positioned in the middle of the LSt, parallel and up against to the lamina medullaris dorsalis (LMD).

Piriform cortex (CPi)

The section corresponding approximately to plate A5.8 in the chicken brain atlas [54] was used for the quantification of Fos-ir cells in the piriform cortex. Contrary to the other brain areas, Fos-ir cells in the PCi were counted manually with the help of a camera lucida (4×objective). The quantification area (length : 1000 µm; height : 520 µm; surface : 52 mm2) was positioned between the edge of the brain and the extension of the lateral ventricle (see Figure 1G).

2.6 Zenk-immunoreactive (ir) cells in the olfactory bulb (OB)

The section corresponding approximately to plate A14.8 in the chicken brain atlas (Kuenzel and Masson, 1988) was used to quantify Zenk expression in the olfactory bulb. The quantification field (0.193 mm2 in portrait position) was placed in the center of the OB (see Figure 1A). For unknown reasons, no expression of Zenk was detected in the olfactory bulb of a substantial number of subjects. The number of Zenk-ir cells was therefore analyzed both in the entire set of data and also after excluding data from subjects showing absolutely no immunoreactivity.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Behavioral parameters were analyzed by one way (male sexual behavior) or two-way (cloacal gland sensitivity after xylocaine) analyses of variance (ANOVA). Assessment of olfactory perception was analyzed by Mann Whitney U tests. Unless otherwise mentioned, one-way ANOVAs were used to analyze the overall differences in Fos immunoreactivity in all areas analyzed. All ANOVAs were followed when appropriate by post-hoc tests using Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) tests to compare experimental groups two by two. A few selected comparisons were also performed by bilateral student t-tests. Differences were considered significant for p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological data

Measures of the androgen-dependent cloacal gland confirmed the marked effect of testosterone on this structure. The average gland area grew from 38.0 ± 1.1 mm2 before implantation of testosterone, to 244.5 ± 6.1 mm2 at the end of the experiment. A two-way ANOVA confirmed that these changes are significant (F1,29 = 965,4, p<0.0001), but there was no group difference (F4,29 = 0.148, p = 0.9624) and no interaction between these two factors (F4,29 = 0.055, p = 0.9940). These data, therefore, indicate that all birds were exposed to a similar activation by androgens throughout the experiment.

The body weight of the five experimental groups was similar at the start and at the end of the experiment. During this period, all subjects slowly gained weight (from 138.0 ± 3.2 to 270.0 ± 4.9 g), as normally observed in this species. No overall difference between groups was detected by a repeated measure ANOVA (F4,29 = 0.116, p = 0.9760), and all groups gained weight at the same rate (interaction : F4,29 = 1.621, p = 0.1956). The change in weight was highly significant (F1,29 = 595.0, p < 0.0001).

3.2. Behavioral Data

3.2.1. Behavioral confirmation of anosmia

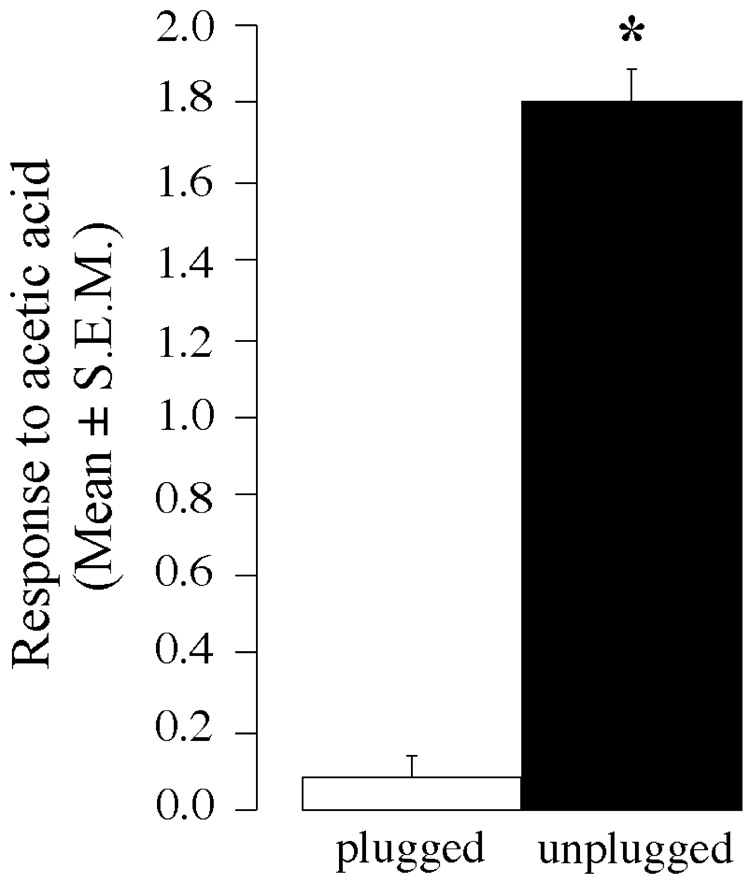

Before nostril plugging, all birds strongly reacted to acetic acid (score of 2) but not to water (score of 0). Quail tolerated the nares occlusion well and breathed via their mouths without apparent difficulty. Between nares occlusion and the day of brain collection, all subjects appeared healthy and no difference in body weight between groups was induced by this experimental manipulation (see above). Males with their nares occluded (plugged condition) and control subjects (unplugged condition) differed significantly in their responses to acetic acid (see Figure 2). Whereas birds in the control condition reacted strongly when exposed to acetic acid there was little overt response by quail with blocked nares (only 3 out of the 13 subjects exhibited a very weak reaction scored as 1 in our qualitative scale). In contrast, exposure to water elicited no major behavioral responses in the two conditions (score of 0 in all plugged and unplugged subjects). The difference in response to acetic acid between plugged and unplugged birds was confirmed by a Mann Whitney U test that demonstrated a significant group difference (U = 0, 2p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Mean responses to acetic acid of male quail with both nostrils plugged with dental cement (plugged condition) or cement applied only to the base of the beak (unplugged condition). * p < 0.05⩦

3.2.2. Cloacal gland sensitivity following xylocaine application

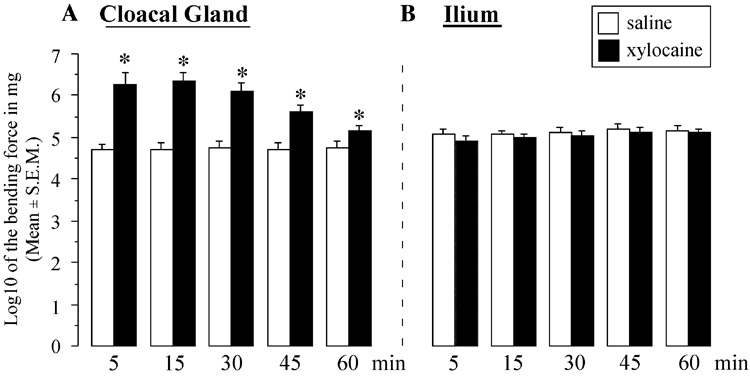

In the control conditions, application of the aesthesiometer filaments produced in all subjects reliable and easily detectable reactions (ruffling of cloacal gland feather or activation of leg muscles for an application on the cloacal gland or ilium respectively). Xylocaine application on the cloacal gland completely eliminated all reactions of most subjects even when tested with the thickest monofilament (1.143 mm diameter corresponding to a force of 446.6 g) at least for tests performed 5 or 15 min later (see Figure 3A). At these two test times, 8 out 10 subjects that were sprayed with xylocaine on the cloacal gland did not respond at all to the thickest monofilament, whereas all saline-treated subjects respond to filament of a much smaller diameter (around 0.380 mm in diameter corresponding to a force of less than 10 g, i.e. a Log smaller than 5; see Figure 3A). This group difference was confirmed by three-way repeated measures ANOVA with time after application, region (cloacal gland vs. ilium) and treatment (saline vs. xylocaine) as repeated factors. This analysis identified a significant effect of all three factors and of all interactions between pairs of these factors (all p≤0.02, data not shown) and most importantly a very significant interaction between the three factors (F4,36 = 7.942, p < 0.0001). Post hoc analysis of this interaction focusing on the comparison at a same time of xylocaine and control subjects revealed that subjects sprayed with xylocaine on their cloacal gland responded significantly less to tactile stimulation than their controls throughout the tests performed between 5 and 60 min. This difference remained significant throughout (p<0.05) despite the fact that the magnitude of the effect progressively decreased with time after 15–30 min. No such effect was observed when testing the tactile sensitivity of the control region, the ilium (see Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of xylocaine (7–8 sprays/subject) on skin sensitivity of the cloacal gland (A) and ilium (B) during the five successive tests at different times post-treatment (5 to 60 min). Data presented are the means of the log 10 of the bending force of the monofilament that elicited a reaction of the subjects stimulated on the center of the cloacal gland or the ilium apterium area. Symbols above the bars summarize the results of the posthoc Fisher PLSD test as follows: * p < 0.05 vs. saline at the same time.

3.2.3. Male sexual behavior during the final 10 min behavioral test

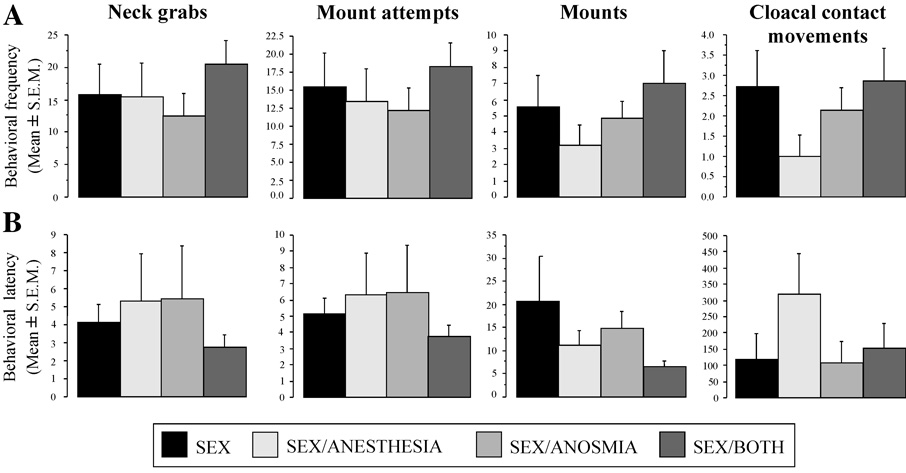

As illustrated in Figure 4, expression of male sexual behavior was not affected in anosmic and/or xylocaine-treated males. When presented to a female during the final 10 min behavioral test, most subjects in all experimental groups showed at least once the complete copulatory sequence including cloacal contact movements. As usual in quail, it was however impossible, based on direct observation, to make sure that actual copulation had occurred. It thus remains possible that males that had their cloacal gland anesthetized did not achieve he ful copulation as regularly as control birds. Testing this fine difference in movement coordination would only be possible with fast cinematography.

Figure 4.

Frequency of the four copulatory behavior patterns (A) and latency of these behaviors (B) during a 10 min test of male sexual behavior under one of the following conditions: (1) males made anosmic by placement of nasal plugs (dental cement blocking both nostrils placed 7 days before testing – SEX/ANOSMIA group); (2) males sprayed with xylocaine on the cloacal gland 5 min before testing (SEX/ANESTHESIA group); (3) males simultaneously exposed to both manipulations (anosmia and cloacal gland anesthesia; SEX/BOTH group); (4) males exposed to control treatments (dental cement on the beak next to the nostrils and spray with water on the cloacal gland; SEX group).

Analysis by ANOVA of the frequencies and latencies of all male copulatory behavior patterns revealed no significant difference between experimental groups (behavioral frequencies : NG : F3,24 = 0.660, p = 0.5846; MA : F3,24 = 0.487, p = 0.6945; M : F3,24 = 0.869, p = 0.4706; CCM : F3,24 = 1.264, p = 0.3090; see Figure 4A; behavioral latencies: NG : F3,24 = 0.442, p = 0.7248; MA : F3,24 = 0.442, p = 0.7248; M : F3,24 = 1.283, p = 0.3029; CCM : F3,24 = 1.149, p = 0.3496; see Figure 4B). Furthermore, nares occluded and/or xylocaine-treated male quail displayed apparently normal rhythmic cloacal sphincter movements as usually observed in sexually mature male when interacting with the female although the observation conditions did not permit an accurate quantification of these contractions.

3.3. Quantification of the Fos-ir cells

As demonstrated by previous studies in quail [24, 28, 58, 82], immunoreactivity for the Fos protein was observed exclusively in cell nuclei with no specific staining in the cytoplasm. The mean numbers of Fos-ir cells observed in the 14 selected brain areas of the five experimental groups are summarized in Table 1. For each brain area, these data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and these statistical results are summarized in Table 1. Due to various technical problems (poor staining, section torn or lost), accurate counts could not always be obtained for each bird and nucleus. The actual number of available data points in each case is provided in the table.

Table 1.

Mean (± SEM) number of Fos-ir cells and summary of the statistical analysis by one-way ANOVAs in the fourteen brain nuclei in the five experimental conditions

| One-way ANOVAs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | CTRL | SEX | SEX/ANESTHESIA | SEX/ANOSMIA | SEX/BOTH | F | (df) | p |

| Fos-ir cells | ||||||||

| Areas related to sexual behavior | ||||||||

| mPOA CA-6 | 9.50 ± 1.7 (n=6) | 20.0 ± 6.5 (n=7) | 24.8 ± 5.4 (n=5) | 18.7 ± 3.8 (n=7) | 17.6 ± 2.9 (n=6) | 1.352 | (4,26) | 0.2777 |

| mPOA CA-4 | 18.5 ± 6.1 (n=4) | 23.0 ± 4.3 (n=7) | 27.6 ± 5.7 (n=5) | 22.1 ± 5.8 (n=7) | 23.5 ± 4.9 (n=8) | 0.265 | (4,26) | 0.8977 |

| mPOA CA-2 | 20.3 ± 3.5 (n=6) | 31.4 ± 7.9 (n=7) | 38.2 ± 10.8 (n=4) | 15.4 ± 1.8 (n=7) | 27.1 ± 5.4 (n=6) | 2.043 | (4,25) | 0.1189 |

| mPOA CA | 19.3 ± 4.0 (n=6) | 40.2 ± 8.3 (n=7)* | 50.6 ± 13.9 (n=5)* | 22.7 ± 3.2 (n=7)Δ | 33.5 ± 4.2 (n=8) | 2.997 | (4,28) | 0.0354 |

| Rostral BSTM | 22.8 ± 2.8 (n=6) | 44.5 ± 7.3 (n=6)* | 16.1 ± 2.6 (n=6)# | 29.5 ± 5.2 (n=6)# | 23.8 ± 2.8 (n=8)# | 5.567 | (4,27) | 0.0021 |

| Caudal BSTM | 34.0 ± 6.0 (n=5) | 79.8 ± 6.2 (n=5)* | 53.8 ± 18.5 (n=5) | 70.3 ± 8.8 (n=6)* | 39.6 ± 9.3 (n=8)#§ | 3.292 | (4,24) | 0.0276 |

| BSTL | 7.1 ± 2.0 (n=6) | 21.5 ± 6.5 (n=6) | 29.1 ± 8.2 (n=6) | 18.3 ± 4.0 (n=6) | 27.7 ± 5.9 (n=8) | 2.216 | (4,27) | 0.0939 |

| SL | 42.5 ± 9.6 (n=6) | 41.6 ± 15.0 (n=6) | 28.2 ± 11.0 (n=5) | 60.2 ± 16.5 (n=5) | 28.6 ± 11.3 (n=8) | 0.963 | (4,25) | 0.4452 |

| TnA | 13.0 ± 2.8 (n=6) | 33.8 ± 4.2 (n=6) | 31.6 ± 6.2 (n=5) | 32.6 ± 7.5 (n=6) | 26.2 ± 4.1 (n=8) | 2.678 | (4,17) | 0.0541 |

| PAG | 15.3 ± 4.6 (n=6) | 26.0 ± 10.9 (n=5) | 45.1 ± 12.0 (n=6) | 36.8 ± 8.4 (n=6) | 48.5 ± 10.4 (n=6) | 1.993 | (4,26) | 0.1252 |

| Areas potentially related to olfaction | ||||||||

| SM | 7.5 ± 2.1 (n=6) | 17.0 ± 3.8 (n=6) | 15.2 ± 3.0 (n=5) | 9.6 ± 1.8 (n=5) | 9.6 ± 1.8 (n=5) | 1.774 | (4,24) | 0.1670 |

| MSt | 35.5 ± 6.1 (n=6) | 41.6 ± 7.1 (n=5) | 37.8 ± 6.2 (n=6) | 39.1 ± 10.1 (n=7) | 47.7 ± 9.5 (n=7) | 0.326 | (4,26) | 0.8579 |

| LSt | 8.3 ± 2.4 (n=6) | 25.6 ± 6.5 (n=6)* | 28.1 ± 6.7 (n=6)* | 26.6 ± 5.2 (n=6)* | 30.2 ± 4.2 (n=8)* | 2.831 | (4,27) | 0.0441 |

| Cpi | 22.6 ± 6.0 (n=6) | 28.8 ± 8.3 (n=6) | 29.3 ± 4.6 (n=6) | 19.8 ± 4.6 (n=5) | 27.6 ± 5.5 (n=8) | 0.427 | (4,26) | 0.7880 |

Results shown in the table indicate for the main factor in the analysis (experimental group) the F ratio (F), corresponding degrees of freedom (df) and associated probability (p).

p < 0.05 vs. CTRL

p < 0.05 vs. SEX

p < 0.05 vs. SEX/ANESTHESIA

p < 0.05 vs. SEX/ANOSMIA

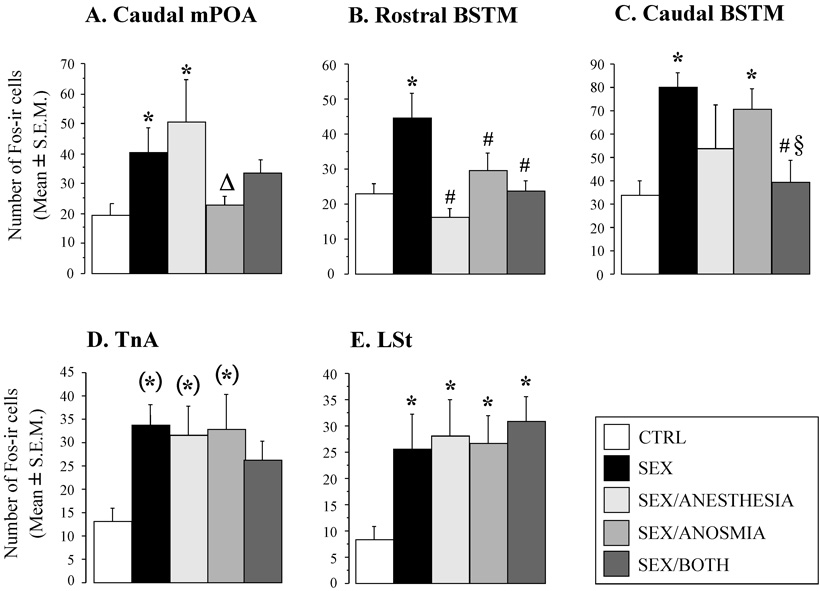

Differential Fos expression in the five experimental groups was observed in several specific brain areas, including the medial preoptic area (mPOA), the medial part of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, both rostral (rBSTM) and caudal (cBSTM) parts, and the lateral striatum (LSt). There was also a trend for an effect of the experimental manipulations in the avian homologue of parts of the mammalian amygdala, the nucleus taeniae of the amygdala (TnA).

Brain nuclei related to male sexual behavior

Medial Preoptic Area (mPOA)

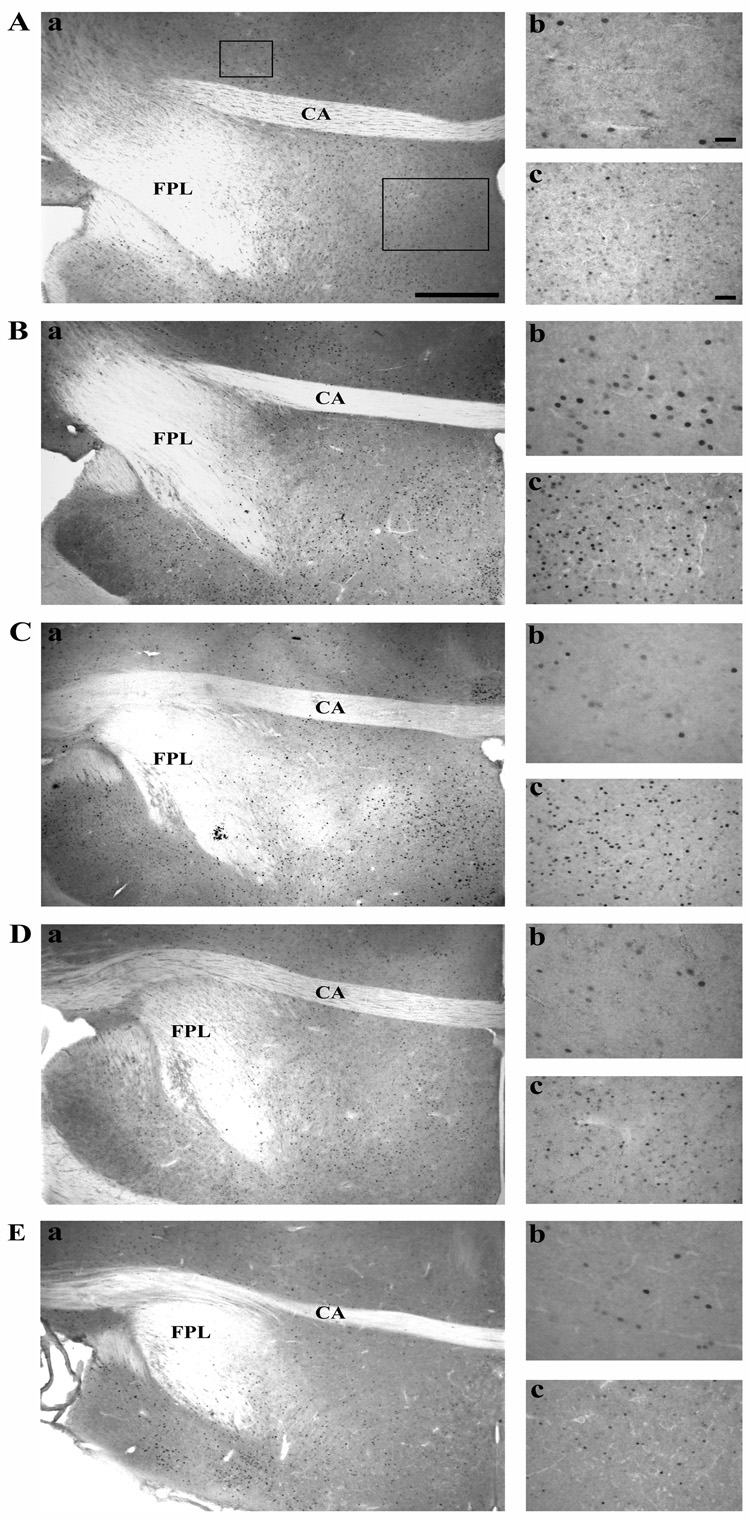

The ANOVA demonstrated significant differences between groups in Fos induction in the most caudal section of the mPOA only (mPOA CA; F4,28 = 2.997, p = 0.0354). As illustrated in Figure 5A, males that had copulated with a female showed a higher Fos expression relative to control birds kept in their home cage. This increase was not affected by the cloacal gland anesthesia but was markedly reduced in subjects deprived of olfaction. Subjects exposed to both treatments exhibited an intermediate level of Fos expression. Post hoc analysis confirmed the significance of most of these differences (see detail in Figure 5A). Representative photomicrographs of sections through the caudal mPOA for the five experimental groups are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Mean (± SEM) number of Fos-ir cells in five brain regions of male quail that were tested for sexual behavior (10 min with a sexually mature female) under one of the following conditions : (1) males made anosmic by placement of nasal plugs (dental cement blocking both nostrils placed 7 days before testing – SEX/ANOSMIA group); (2) males sprayed with xylocaine on the cloacal gland 5 min before testing (SEX/ANESTHESIA group); (3) males simultaneously exposed to both manipulations (anosmia and cloacal gland anesthesia; SEX/BOTH group); (4) males exposed to control treatments (dental cement on the beak next to the nostrils and spray with water on the cloacal gland; SEX group). A 5th group received both control treatments and birds were only handled and replaced in their home cage without being presented with a female (CTRL group). Symbol above the bars summarize the results of the posthoc Fisher PLSD test as follows: * p < 0.05 vs. CTRL; # p < 0.05 vs. SEX; Δ p < 0.05 vs. SEX/ANESTHESIA; § p < 0.05 vs. SEX/ANOSMIA; (*) vs. CTRL following a nearly significant one-way ANOVA (p < 0.06).

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs illustrating areas of the quail brain where a differential induction of Fos expression was observed in the five experimental groups (A: CTRL group; B : SEX group; C : SEX/ANESTHESIA group; D : SEX/ANOSMIA group and E : SEX/BOTH group). In panels A through E, Fos expression is illustrated in: (a) the caudal mPOA and the rostral BSTM at low magnification (4× objective); (b) the rostral BSTM at high magnification (40× objective); (c) the caudal mPOA at medium magnification (20× objective). The boxes in panel A.a. indicate the position of the fields shown at higher magnification. Scale bars = 500 µm in a, 50 µm in b and 100 µm in c. CA, commissura anterior; FPL, fasciculus prosencephali lateralis.

An additional ANOVA comparing control subjects (CTRL group, n = 6) and birds exposed to a female after pooling those that had copulated in the absence (SEX and SEX+ANESTHESIA groups, n = 12) or the presence (SEX+ANOSMIA and SEX+BOTH groups, n = 15) of the nasal plug confirmed the presence of a significant difference between these three groups (F2,30 = 4.756, p = 0.0161). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc tests showed that the numbers of Fos-ir cells in unplugged birds was significantly higher relative to control birds (p = 0.0083) and to plugged birds (p = 0.0268).

The global pattern of Fos expression in the mPOA CA-2 in the five groups looked very similar to the pattern observed in the more caudal section of the mPOA (mPOA CA), with numerically greater Fos expression in the SEX and SEX/ANESTHESIA groups. However, the one-way ANOVA identified no significant difference between the five experimental groups in this brain region (F4,25 = 2.043, p = 0.1189). No trace of such effects could be detected in the more rostral parts of the mPOA.

Bed nucleus of the Stria Terminalis, Medial part (BSTM)

One-way ANOVAs also identified significant effects of the experimental conditions on the number of Fos-ir cells observed both in the rostral (F4,27 = 5.567, p = 0.0021) and the caudal parts of the BSTM (F4,24 = 3.292, p = 0.0276). Interestingly, the pattern of c-fos induction was slightly different in these two sub-regions of the BSTM (see Figure 5B–C for comparison). In the rostral BSTM, post hoc tests revealed that Fos expression was significantly greater in the SEX group relative to all other groups (all’s p < 0.05; Figure 5B), which all displayed a nearly identical Fos expression (see Figure 6 for representative photomicrographs). In the caudal BSTM, the level of Fos expression in both the SEX and SEX/ANOSMIA groups was higher relative to subjects in the CTRL and SEX/BOTH groups (both p > 0.05; Figure 5C) whereas subjects in the SEX/ANESTHESIA group showed an intermediate c-fos induction (Figure 5C).

Other brain areas related to male sexual behavior

Besides the mPOA and the BSTM, seven additional brain regions were quantitatively analyzed for Fos expression based either on previous work showing IEG induction in these regions after performance of male sexual behavior in quail or on their known involvement in the brain circuits controlling this behavior. An one-way ANOVA on the number of Fos-ir cells in the nucleus taeniae of the amygdala (TnA) revealed a nearly significant difference between the different groups (F4,26 = 2.678, p = 0.0541), resulting mainly from a higher c-fos induction in males that had been allowed to copulate with a female by comparison with subjects exposed to the control procedure (see Figure 5D). Post-hoc tests suggested that this increase was significant in 3 of the 4 groups exposed to females but these differences can only be considered as suggestions for future experiments since the overall differences as measured by ANOVA were not significant.

In the lateral septum (SL), the ANOVA failed to reveal the presence of significant differences between the five experimental groups (LS: F4,25 = 0.963, p = 0.4452). In the BSTL, males who performed copulatory behavior displayed a higher number of Fos-ir cells compared to birds kept in their home cage but this difference did not reach statistical significance (F4,27 = 2.216, p = 0.0939).

Finally, based on previous Fos studies in quail [24, 58], we also analyzed the number of Fos-ir cells in one section through the periaqueductal gray (PAG) but no significant difference between the five experimental groups was found in this nucleus (F4,26 = 1.993, p = 0.1252) although larger numbers of positive cells were present in birds that has been exposed to the female as compared to birds kept in their home cage (see Table 1; comparisons CTRL vs. Pooled other 4 groups: t = 2.246, df = 29, p = 0.0325). The same comparisons (CTRL vs. 4 groups exposed to the female) by t tests confirmed the presence of a significant Fos induction in the most rostral section through the mPOA (mPOA CA-6: t = 2.107, df = 29 , p = 0.0439), the BSTL (t = 2.604, df = 30, p = 0.0142) and the TnA (t = 3.119, df = 29, p = 0.0041) but not in the other areas related to sexual behavior (POM CA-4 : t = 0.762, p = 0.4522; POM CA-2 : t = 0.898, p = 0.3766; POM CA : t = 1.891, p = 0.0680; rBSTM : t = 0.833, p = 0.4116 ; cBSTM : t = 1.767, p = 0.0886 ; SL : t = 0.284, p = 0.7788)

Other brain areas related to olfaction

In three of the four other brain nuclei potentially implicated in avian olfactory pathway, namely the medial septum (SM), the medial striatum (MSt) and the piriform cortex (CPi), no significant difference in Fos expression could be detected between the five experimental groups (see Table 1). In contrast, the one way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the experimental manipulations in the lateral striatum (LSt: F4,27 = 2.831, p = 0.0441). Post hoc tests following the ANOVA indicated that this induction was not affected by the various forms of sensory deprivations (see Figure 5E) but Fos expression was significantly higher in all subjects allowed to copulate with a female relative to subjects in the CTRL group (t=3.439, df=30, p=0.0017). No such induction of FOs expression by copulation was observed in the other brain areas related to olfaction (SM : t = 1.923, p = 0.0650; MSt : t = 0.676, p = 0.5042; CPi : t = 0.610, p = 0.5469).

Olfactory bulb

Based on identified (very small size, thickness, loss and damage to the sections) and unidentified technical reasons, Fos immunostaining in the olfactory bulb was highly variable (only a small number of subjects showed any Fos immunoreactivity and in all cases immunostaining was very weak). We hypothesized therefore that another immediate early gene would provide a more consistent pattern of activation in this ustrcture. One series of sections through the olfactory bulbs were thus stained for zenk (also called egr-1 or zif-268 in mammals; Mello et al., 1992.), another immediate early gene known to be induced by sexual stimulations in male quail (Ball et al., 1997; Charlier et al., 2005).

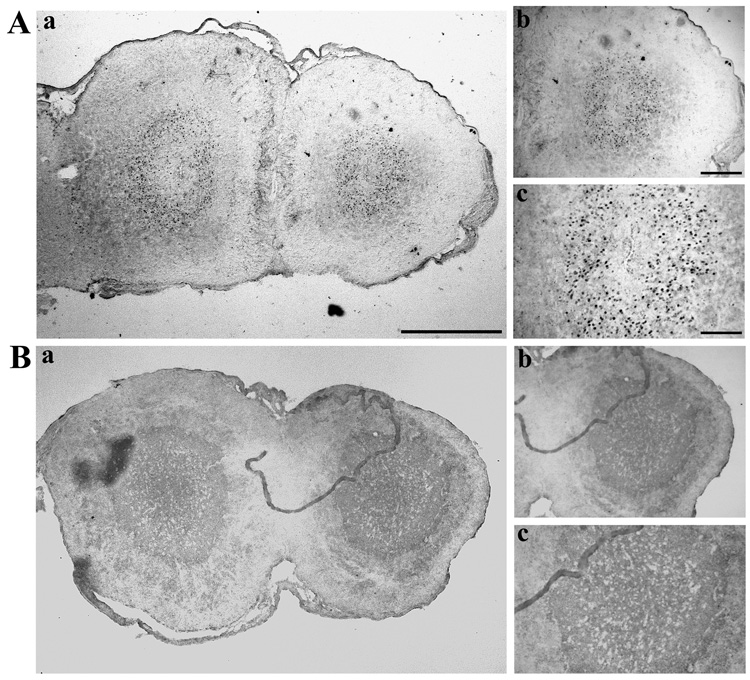

Representative micrographs of sections through the olfactory bulbs stained for the Zenk protein are shown in Figure 7. In many, but not all, subjects that had been exposed to the female without nasal plugs, a large number of Zenk-ir cells was observed in the central part of the olfactory bulb that should correspond to the granular cell layer in other amniotes. These cells were not present or present in smaller densities in control birds that had not copulated with the females and in birds that had copulated but with a nasal plug.

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs illustrating zenk expression in the olfactory bulb of male quail that copulated with a female in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of a nasal plug. Zenk expression in the olfactory bulb is illustrated at: (a) low magnification (4 × objective); (b) at medium magnification (10 × objective); (c) at high magnification (20 × objective). Scale bars = 500 µm in a, 200 µm in b and 100 µm in c.

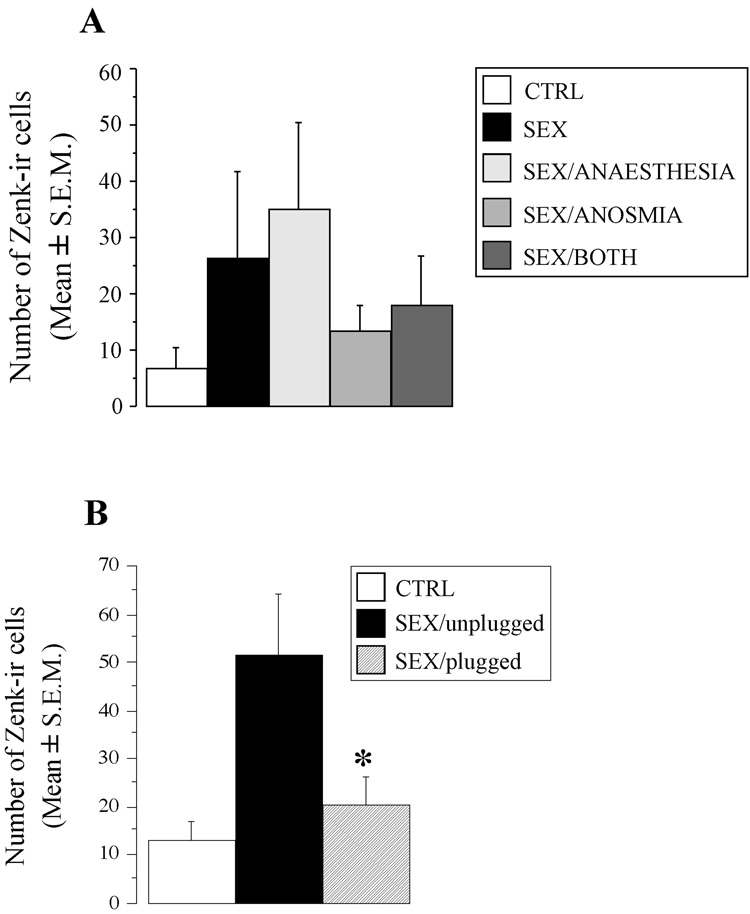

One-way ANOVA of the number of Zenk-ir cells in the olfactory bulb showed no significant effect of the experimental treatments (F4,24 = 0.785, p = 0.5462; Figure 8A). There was however an obvious numerical increase in the number of immunoreactive cells in the two groups of subjects that had been allowed to copulate with the female while their nares were unplugged (groups SEX and SEX/ANESTHESIA) as compared to the control subjects or with subjects that copulated with the female while their nostrils were plugged (groups SEX/ANOSMIA AND SEX/BOTH). Data were thus reanalyzed after pooling birds that copulated in the absence (unplugged groups, n = 12) or in the presence (plugged group, n = 13) of the nasal plug. A one-way ANOVA comparing these two groups of birds and the controls (CTRL group, n = 4) still revealed no significant difference between these three groups (F2,26 = 1.489, p = 0.2443). This analysis, however, still included a large number of birds in which no Zenk-ir cells at all were present in the sections. After removing these birds that exhibited no expression, a significant effect appeared in the number of Zenk-ir cells detected in males from these three experimental conditions (n = 10 in the SEX/plugged group; n = 7 in the SEX/unplugged group; n = 2 in the CTRL group; F2,16 = 3.742, p = 0.0464; see Figure 8B). Post hoc analysis showed that the numbers of Zenk-ir cells in the SEX/unplugged group was significantly higher relative to the SEX/plugged group (p = 0.0231). The difference with the control group was not fully significant (p = 0.0731).

Figure 8.

Zenk expression in the olfactory bulb. (A) Mean (± SEM) number of Zenk-ir cells in the 5 experimental groups (see methods and Legend of figure 5 for their full description). (B) Mean (± SEM) number of Zenk-ir cells in males allowed to copulate with a female after their nares were occluded (SEX/plugged group) or not (SEX/unplugged group) and in control birds (CTRL group). Males that showed no zenk expression at all were excluded from the analysis. * p < 0.05 compared to the SEX/unplugged group.

4. Discussion

After copulation, Japanese quail display a pattern of Fos induction in the mPOA and BSTM that is very similar to what has been described in rats [24, 58, 82]. It has been shown by lesion experiments that, in rats, this Fos induction is related largely to the processing of olfactory information and of feedback stimuli originating in the penis [18]. The fact that birds have long been considered to be microsmic, if not anosmic [29, 57] although this idea is contradicted by a substantial body of evidence (see [42] for a recent review) and most lack an intromittent organ (i.e., penis; [21, 23]) raises the question of the mechanisms causing Fos expression in their brain following copulation. We demonstrate here that in Japanese quail, as in rats, Fos expression induced by male sexual behavior in the mPOA and BSTM is affected by manipulations that modify the olfactory and/or somatosensory stimuli originating from the genital/cloacal region. However, anosmia and cloacal gland anesthesia did not inhibit the expression of male sexual behavior, suggesting that the decrease in Fos expression in the mPOA and BSTM could not be caused by a suppression of motor outputs. These results therefore call for a re-analysis of the role of olfaction in the control of sexual behavior in birds and stress the potential importance of sensory inputs from the genital region in the expression of this behavior even in species that lack an intromittent organ.

4.1. Efficiency of olfactory and somatosensory deprivation

Deprivation of olfactory inputs was achieved by bilateral nares occlusion with dental cement. This method has been validated in previous studies in birds [50, 68, 69] and in mammals [52]. We confirmed that blockade of the nostrils suppresses nearly completely the well-characterized behavioral reactions to acetic acid and therefore presumably its detection. Control birds displayed a clear reaction toward acetic acid, but males with nares occluded were in general not affected by this olfactory stimulus, demonstrating the effectiveness of the anosmia procedure. One might argue that the olfactory stimulus used here is so strong that it might be detected by the trigeminal as well as by the olfactory system. This could explain the very weak reaction observed in three of the plugged subjects. Such a cross-reaction with other sensory systems would raise a potentially serious issue about the interpretation of our results if the behavioral reaction to the stimulus had not been blocked by the nares occlusion. Given that this experimental manipulation did almost completely block the behavioral reactions, it does not seem that the potency of the stimulus represents a confound in the present study.

In other subjects, xylocaine was used to suppress somatosensory inputs originating from the cloacal gland region. As previously demonstrated by Evrard and Balthazart [38], the xylocaine-sprayed cloacal gland is insensitive to tactile stimulation as assessed by the Semmes-Weinstein test. Accordingly, we confirmed here that even the application of the thickest monofilament of the aesthesiometer failed to elicit a reaction of the cloacal gland feathers in xylocaine-treated males. In contrast, these animals exhibited a normal response in the adjacent ilium region, suggesting that the anesthesia was specifically restricted to the cloacal region. This preliminary experiment also indicated that the duration of this local anesthesia is equal to or greater than 15–30 min confirming therefore that the tests for sexual behavior were indeed performed at a time (5–15 min after spraying) when the cloacal gland area was insensitive to tactile stimulation.

4.2. Effect of olfactory and somatosensory deprivations on male quail sexual behavior

Bilateral nares occlusion and cloacal gland anesthesia, alone or in combination, failed to disrupt male sexual behavior in quail, suggesting that olfactory and/or somatosensory inputs are not essential in the expression of male sexual behavior. The importance of olfactory information in the control of behavior in birds is generally thought to be minimal (Del Hoyo et al., 1992), but a number of studies indicate that chemical information originating in the female could modulate some aspects of male reproductive behavior (reviewed in Hagelin, 2007). The first experiments yielding indirect evidence for a role of olfactory signals in the control of courtship displays in an avian species involved male mallards (Anas platyrhynchos). Males whose olfactory nerves were severed exhibited significantly fewer sexual behaviors and social displays toward females than control males (Balthazart and Schoffeniels, 1979). In addition, males could also be conditioned to copulate preferentially with females bearing an artificial odor [13]. Based on biochemical analyses, it was later suggested that the secretion of the uropygial gland could in this species produce sex specific chemosignals potentialy modulated by the endocrine state of the female [49]. More recently, it was shown that female crested auklets (Aethia cristatella) produce during the reproductive season a tangerine-scented social odor that play a key role in sexual attraction in this species [43].

In mammals, a central role for olfactory cues in regulating sexual behavior has been suggested since at least the seventies based on the observation that olfactory bulbectomy completely eliminated male sexual behavior in mice [77], rats [46, 55] and hamsters [30, 63]. Because the olfactory bulbs may have neural functions other than those directly related to olfaction, several authors attempted to produce anosmia more specifically by damaging the olfactory epithelium with the infusion of zinc sulphate or dichlobenil [51, 87] or by using male mice carrying a targeted disruption of the Cyclic nucleotide-gated channel subunit A2 (CNGA2) channel, which is expressed in the olfactory epithelium and mediates odor detection [56]. All these experiments found that dysfunctions of the olfactory epithelium produce major decrements in sexual behavior similar to those observed after olfactory bulbectomy. However, other experiments have produced contradictory results in male hamsters [71], dogs [45], ferrets [52], cats [4] and rhesus monkeys [41, 61] in which peripheral anosmia failed to disrupt sexual behavior. These discrepancies could be related to the previous sexual experience of the subject that might mitigate the disruptive effects of olfactory deprivation on male sexual behavior as is clearly the case in male hamster [66, 86]. In this context, it should be noted that we used sexually experienced male quail in these experiments. The present data therefore do not rule out completely a possible effect of olfactory deprivation on male sexual behavior that would be only observed in sexually naive birds. Further experiments are needed to address this possibility.

Quail possess a large sexually dimorphic, androgen-sensitive, external protuberance of the caudal lip of the cloaca, the cloacal gland [78]. Rhythmic movements of the cloacal sphincter muscles (RCSM) are used by reproductively active males just before copulation to produce a stiff meringue-like foam that is transferred into the female’s cloaca during copulation and that enhances the male fertilization success [81]. Thus, the ability to display RCSM is of particular importance in the reproductive success of male quail.

When paired with a female, males perform a sequence of stereotyped actions in which they first grab the feathers of the female in the neck region, try to mount on her back, eventually succeed in mounting her and position both feet on her back and then finally fall backwards, open their wings and try to move their cloaca in contact with the female’s cloaca. This behavior is commonly recorded as cloacal contact movement irrespective of whether successful copulation has been achieved or not, because this success is difficult to assess in an accurate manner [2, 48]. In the present experiment, copulatory behavior was not affected in male quail treated with xylocaine despite the fact that the xylocaine–sprayed cloacal region was 10–100 fold less sensitive to tactile stimulation relative to control birds. In addition these birds still displayed apparently normal contractions of the cloacal gland even if detailed quantification of this aspect of the behavior could not be performed. These results suggest that somatosensory inputs originating from the skin in the cloacal gland region only play a minor role in the expression of male sexual behavior in quail. In male rats, Baum and Everitt [18] showed that application of lidocaine anaesthetic to the penis attenuated intromission and ejaculation while augmenting the display of mounts with pelvic thrusting. This confirmed previous research demonstrating that reduced sensory feedback from the penis modifies but fails to eliminate sexual activity. Application of a topical anaesthetic may prevent intromission and ejaculation but mounting continues at a high rate [3, 79].

The lack of detrimental effects on male quail sexual behavior of the deprivation of olfactory stimuli and of somatosensory cues from cloacal gland is in agreement with the traditional view that sexual behavior in birds relates mostly on visual and acoustic cues. In male quail, as is true of many Galliform species, visual cues appear to be of primary importance in the control of social interactions and seem to be sufficient to elicit copulatory responses. For example, Domjan and Nash [34] demonstrated that static visual cues, as obtained from a taxidermically prepared model, are sufficient to induce social proximity behavior and suppress crowing in male quail in the absence of behavioral, auditory, and olfactory cues. The behavior induced by the female model was primarily elicited by visual cues from the head and neck region that are sexually dimorphic in quail. Additional stimuli, especially vocalizations and behavioral cues such as copulation solicitation, will enhance this response and probably play a role under natural conditions. It was also demonstrated that male quail spend more time in front of a window providing a view of a female than a view of a male [33] and that this discrimination was based on sex-typical visual features (head and neck feathers) of the stimulus birds [32, 35].

The present experiment does not however completely exclude a potential role of olfactory or genital somatosensory stimuli in the control of sexual behavior in birds. As stated above, these stimuli could be more important in naïve than in sexually experienced birds. It is also important to keep in mind that Japanese quail are semi-domesticated animals. They have been selected for high rates of reproduction and therefore display a very intense sexual behavior especially if males are normally separated from the females except during the sexual behavior tests, as was done in these studies. This testing procedure could help explain why these birds continue to display an active sexual behavior even in situations that are not associated with the full range of stimuli that elicit sexual behavior under normal conditions.

4.3. Effects of anosmia and/or cloacal gland anesthesia on Fos expression induced by mal sexual behavior

The medial preoptic area (mPOA) is an essential brain site for the regulation of male copulatory behavior in quail [64] and homologous areas play a similar role in mammals [31, 47, 59]. In quail, a large number of studies based on stereotaxic electrolytic lesions [9, 16] or steroid implantation [15, 17] have confirmed the critical role of this nucleus in the regulation of male sexual behavior [11]. The present study provides additional confirmation that the mPOA is involved in the expression of male sexual behavior given that a significant increase in Fos expression was found in this area in birds that had copulated with a female as compared to birds that remained in their home cages. Furthermore, the present results suggest that olfactory cues may play a role in the activation of the mPOA and the BSTM following expression of male sexual behavior, since c-fos expression was no longer increased in these nuclei in birds that had their nares occluded.

It is also particularly interesting to note that this effect was observed only in the caudal part of the mPOA. This regional specificity agrees with previous reports demonstrating that this sub-region of the mPOA is preferentially involved in the control of copulatory behavior as demonstrated by lesions and implants studies [9, 17] and also by previous immunocytochemical studies analyzing Fos expression in the brain of males that had been allowed to copulate with a female [58, 82].

In mammals, the olfactory information that plays a role in the activation of sexual behavior in males and females reaches the POA through a pathway that includes the cortico-medial amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTM) [22, 53, 59]. In vivo tract-tracing has revealed the presence in quail of an important projection from the arcopallium (homologous to parts of the mammalian amygdala) and in particular the nucleus taeniae of the amygdala to the medial preoptic nucleus [8], suggesting that olfactory inputs could reach the medial preoptic nucleus through a similar route in quail. However, we did not find any effect of olfactory deprivation on Fos expression induced by male sexual behavior in the TnA. Furthermore, no effect of the sensory deprivations implemented in this study was detected on Fos expression in brain nuclei such as the medial and lateral striatum, the medial septum or the piriform cortex that are presumably part of the olfactory pathway [20, 40, 72, 74]. It remains therefore difficult to interpret definitely the changes in Fos activation that were detected here in the caudal mPOA and in the BSTM in birds subjected to sensory deprivations before copulation. Additional experiments are needed to explain this apparent discrepancy between quail and mammals.

It is first possible that olfactory information is transmitted to the mPOA and BSTM by a route that does not involve the TnA nor other areas known to be associated with olfaction. It is also possible that olfactory cues originating from the female during copulation are not intense enough to induce Fos expression in the first relays of olfactory pathway or may activate other aspects of the functioning of these pathways that could only be detected by other markers of neuronal activation such as other immediate early genes (egr1, also called zenk in birds: [7, 24, 60] or the phosphorylation of intracellular signaling proteins such as MAPK [36]. In agreement with this idea, although no convincing Fos immunoreactivity could be detected in the olfactory bulb, a relatively low level of expression of zenk, another IEG, was detected in this first olfactory relay. Indeed, males that expressed zenk in the olfactory bulb revealed quantitatively fewer Zenk-ir cells if their nares were occluded (plugged condition) as compared to unplugged birds. To our knowledge, this is the first report of immediate early gene activation in the avian olfactory bulb and further experiments should be carried out to confirm this pattern of activation. Moreover, more specific methods for inducing anosmia should also be used to test whether the present results specifically relate to the deprivation of olfactory stimuli or to some other aspect of the experimental manipulation such as the occlusion of the air flow though the nostrils, even if this alternative explanation seems unlikely based on the behavior of the subjects.

The medial preoptic area (mPOA) is also a key site for the control of motor outputs related to sexual behavior as demonstrated by prominent connections between the mPOA and the periaqueductal gray [11]. Because the PAG also displays multiple connections with more caudal mesencephalic and pontine structures [12], this brain structure is though to represent a premotor nucleus connecting the forebrain with specific brainstem nuclei as part of a network involved in the control of male sexual behavior [6]. Anatomical and functional studies demonstrate that the homologous neuronal circuitry plays a key role in the control of male sexual behavior in rats [62, 75]. This hypothesis is further supported in quail by the demonstration that aromatase-immunoreactive neurons located in the lateral part of the POM send major projections to PAG [1]. There is therefore converging evidence suggesting that the mPOA regulates the pre-motor aspects of male sexual behavior in part through its projections to PAG and this notion agrees with the observation that in a previously published study from our laboratory, increased Fos expression was detected in the PAG following performance of copulatory sexual behavior [24]. However, in the present experiment, no significant difference in Fos expression in the PAG was found between the five experimental groups and no effect of olfactory and somatosensory deprivation was observed in this nucleus. It should be pointed out, however, that the absence of Fos induction in the PAG following expression of copulation potentially relates to a low statistical power of the study due to the repartition of a limited number of subjects in five experimental groups. If the number of Fos-ir cells in PAG is compared by a t-test between the control group and the sum of all other groups that were all allowed to copulate with a female, a highly significant induction is then detected.

Like the mPOA, the BSTM is directly involved in the control of male sexual behavior in that experimental manipulations (lesion and implantation studies) of this region affect the male’s ability to copulate with a female in quail [9] as has also been observed in mammals [25, 37, 70, 84]. Previous studies on Fos and Zenk reported a clear activation of this nucleus following expression of sexual behavior in quail [7, 24, 58, 82] and in mammals [18, 27, 65, 85]. Here we demonstrate that Fos expression following male sexual behavior in both the rostral and the caudal BSTM is activated after copulation in a way that is affected by both olfactory and somatosensory deprivation. Interestingly, the pattern of these effects was slightly different in the two regions. Both sensory modalities, alone or in combination seem to be necessary to activate the rostral BSTM and a significant decrease in Fos expression is observed when either type of input is experimentally blocked. In contrast, in the caudal BSTM, only the combination of both sensory modalities deprivation significantly reduced Fos expression as compared to the expression levels observed in the SEX group so that in the SEX/BOTH subjects activation was no longer above levels found in subjects kept in their home cage. This finding is consistent with other studies [18, 26] in male rats showing differential activation of rostral and caudal regions of the posteromedial BNST following mating behavior.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that although copulatory performance is not affected in male quail by an experimental deprivation of olfactory stimuli and of somatosensory feedback from the cloacal region, these manipulations affect brain activation at specific sites such as the mPOA and BSTM. The mechanisms mediating these anatomically specific modifications in central Fos expression could reflect the use by the bird of olfactory or genital sensory information during copulation but alternative explanations are definitely possible and should be considered in future experiments.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NIH / MH50388) to GFB and the Belgian FRFC 2.4562.05 to JB. We thank Dr. Lutgarde Arckens (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium) for providing the Fos antibody used in these studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Absil P, Riters LV, Balthazart J. Preoptic aromatase cells project to the mesencephalic central gray in the male Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) Horm Behav. 2001;40:369–383. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkins EK, Adler NT. Hormonal control of behavior in the Japanese quail. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1972;81:27–36. doi: 10.1037/h0033315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler N, Bermant G. Sexual behavior of male rats: effects of reduced sensory feedback. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1966;61:240–243. doi: 10.1037/h0023151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson LR, Cooper ML. Olfactory deprivation and mating behavior in sexually experienced male cats. Behav Biol. 1974;11:459–480. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(74)90785-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aste N, Balthazart J, Absil P, Grossmann R, Mülhbauer E, Viglietti-Panzica C, Panzica GC. Anatomical and neurochemical definition of the nucleus of the stria terminalis in Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) J Comp Neurol. 1998;396:141–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball GF, Balthazart J. Hormonal regulation of brain circuits mediating male sexual behavior in birds. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:329–346. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball GF, Tlemçani O, Balthazart J. Induction of the Zenk protein after sexual interactions in male Japanese quail. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2965–2970. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709080-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balthazart J, Absil P. Identification of catecholaminergic inputs to and outputs from aromatase-containing brain areas of the Japanese quail by tract tracing combined with tyrosine hydroxylase immunocytochemistry. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382:401–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balthazart J, Absil P, Gerard M, Appeltants D, Ball GF. Appetitive and consummatory male sexual behavior in Japanese quail are differentially regulated by subregions of the preoptic medial nucleus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6512–6527. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06512.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balthazart J, Ball GF. The Japanese quail as a model system for the investigation of steroid-catecholamine interactions mediating appetitive and consummatory aspects of male sexual behavior. Ann Rev Sex Res. 1998;9:96–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balthazart J, Ball GF. Topography in the preoptic region: differential regulation of appetitive and consummatory male sexual behaviors. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2007;28:161–178. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balthazart J, Dupiereux V, Aste N, Viglietti-Panzica C, Barrese M, Panzica GC. Afferent and efferent connections of the sexually dimorphic medial preoptic nucleus of the male quail revealed by in vitro transport of DiI. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;276:455–475. doi: 10.1007/BF00343944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balthazart J, Schoffeniels E. Pheromones are involved in the control of sexual behaviour in birds. Naturwissenschaften. 1979;66:55–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00369365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balthazart J, Schumacher M, Ottinger MA. Sexual differences in the Japanese quail: behavior, morphology and intracellular metabolism of testosterone. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1983;51:191–207. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(83)90072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balthazart J, Surlemont C. Androgen and estrogen action in the preoptic area and activation of copulatory behavior in quail. Physiol Behav. 1990;48:599–609. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90198-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balthazart J, Surlemont C. Copulatory behavior is controlled by the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the quail POA. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25:7–14. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90246-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balthazart J, Surlemont C, Harada N. Aromatase as a cellular marker of testosterone action in the preoptic area. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:395–409. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baum MJ, Everitt BJ. Increased expression of c-fos in the medial preoptic area after mating in male rats: role of afferent inputs from the medial amygdala and midbrain central tegmental field. Neurosci. 1992;50:627–646. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baylé JD, Ramade F, Oliver J. Stereotaxic topography of the brain of the quail. J Physiol (Paris) 1974;68:219–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bingman VP, Casini G, Nocjar C, Jones TJ. Connections of the piriform cortex in homing pigeons (Columba livia) studied with fast blue and WGA-HRP. Brain Behav Evol. 1994;43:206–218. doi: 10.1159/000113635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birkhead TR, Moller AP. Sperm competition in birds. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan PA, Zufall F. Pheromonal communication in vertebrates. Nature. 2006;444:308–315. doi: 10.1038/nature05404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briskie JV, Montgomerie R. Sexual selection and the intromittent organ of birds. J Avian Biol. 1997;28:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlier TD, Ball GF, Balthazart J. Sexual behavior activates the expression of the immediate early genes c-fos and Zenk (egr-1) in catecholaminergic neurons of male Japanese quail. Neurosci. 2005;131:13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claro F, Segovia S, Guilamon A, Del Abril A. Lesions in the medial posterior region of the BST impair sexual behavior in sexually experienced and inexperienced male rats. Brain Res Bull. 1995;36:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00118-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coolen LM, Peters HJ, Veening JG. Distribution of Fos immunoreactivity following mating versus anogenital investigation in the male rat brain. Neurosci. 1997;77:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coolen LM, Peters HJPW, Veening JG. Anatomical interrelationships of the medial preoptic area and other brain regions activated following male sexual behavior: A combined Fos and tract-tracing study. J Comp Neurol. 1998;397:421–435. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980803)397:3<421::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Hondt E, Vermeiren J, Peeters K, Balthazart J, Tlemçani O, Ball GF, Duffy DL, Vandesande F, Berghman LR. Validation of a new antiserum directed towards the synthetic c-terminus of the FOS protein in avian species: immunological, physiological and behavioral evidence. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;91:31–45. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J. Handbook of the birds of the world. Lynx Edition. vol 1. Barcelona: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devor M, Murphy MR. The effect of peripheral olfactory blockade on the social behavior of the male golden hamster. Behav Biol. 1973;9:31–42. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(73)80166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dominguez JM, Hull EM. Dopamine, the medial preoptic area, and male sexual behavior. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domjan M. Going wild in the laboratory: Learning about species-typical cues. In: Medin D, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. vol 38. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 155–186. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Domjan M, Hall S. Determinants of social proximity in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica): male behavior. J Comp Psychol. 1986;100:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Domjan M, Nash S. Stimulus control of social behaviour in male Japanese quail. Anim Behav. 1988;36:1006–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domjan M, O'Vary D, Greene P. Conditioning of appetitive and consummatory sexual behavior in male Japanese quail. J Exp Anal Behav. 1988;50:505–519. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]