Abstract

Cyclin(-D-)-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitors of the Ink4 family specifically bind to Cdk4 and Cdk6, but not to other Cdks. Ink4c and Ink4d mRNAs are maximally and periodically expressed during the G2/M phase of the cell division cycle, but the abundance of their encoded proteins is regulated through distinct mechanisms. Both proteins undergo polyubiquitination, but the half life of p18Ink4c (~10 hours) is much longer than that of p19Ink4d (~2.5 hours). Lysines 46 and 112 are preferred sites of ubiquitin conjugation in p18Ink4c, although substitution of these and other lysine residues with arginine, particularly in combination, triggers protein misfolding and accelerates p18Ink4c degradation. When tethered to either catalytically active or inactive Cdk4 or Cdk6, polyubiquitination of p18Ink4c is inhibited, and the protein is further stabilized. Conversely, in competing with p18Ink4c for binding to Cdks, cyclin D1 accelerates p18Ink4c turnover. In direct contrast, polyubiquitination of p19Ink4d is induced by its association with Cdks, whereas cyclin D1 overexpression retards p19Ink4d degradation. Although it has been generally assumed that p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d are biochemically similar Cdk inhibitors, the major differences in their stability and turnover are likely key to understanding their distinct biological functions.

Keywords: Ink4 genes, p18Ink4c, p19Ink4d, ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, Cdk4, Cdk6, cyclin D1

Introduction

Progression through the mammalian cell division cycle is positively regulated by a family of serine/threonine protein kinases, the cyclin-dependant kinases (Cdks), whose activities are opposed in turn by two general classes of polypeptide Cdk inhibitors.1,2 The mitotic and S-phase holoenzymes (comprised of Cdk1 and Cdk2, respectively, which are allosterically regulated by cyclins B, A and E) can be restrained by proteins of the Cip/Kip family (p21Cip1, p27Kip1 and p57Kip2). These polypeptides inhibit kinase activity and substrate selection by binding to both the Cdk and cyclin subunits of the assembled cyclin-Cdk holoenzymes.3,4 In contrast, the activities of the cyclin D-dependent G1 phase kinases, Cdk4 and Cdk6, are not readily blocked by Cip/Kip proteins,2,5,6 but instead are specifically inhibited by members of the Ink4 family (originally named for their ability to inhibit Cdk4).1,7 Unlike the Cip/Kip proteins, the Ink4 proteins bind directly to Cdk4 or Cdk6 (but not to other Cdks) to alter their structure and prevent their interaction with, and activation by, the three different D-type cyclins, D1, D2 and D3.8–10

The Ink4 protein family is comprised of four members, p16Ink4a, p15Ink4b, p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d, whose molar potencies as Cdk inhibitors in a test tube are essentially indistinguishable.11–15 The first discovered members, p16Ink4a and p15Ink4b, primarily consist of four tandem ankyrin repeat units and are encoded by two closely linked homologous genes (Ink4a and Ink4b in the mouse or CDKN2A and CDKN2B in humans) that likely arose through duplication.7 These two genes are not generally expressed during fetal development or in young adult tissues, although they are now recognized to accumulate as animals age.16–20 They are induced by various forms of oncogenic stress and their expression facilitates the temporal evolution of a complex cellular senescence program that helps to eliminate incipient tumor cells.21 As such, Ink4a, in particular, is a potent tumor suppressor gene whose loss-of-function by mutation, deletion or epigenetic silencing frequently occurs in many different forms of cancer. Recent data indicate that the activity of the Ink4b gene provides a second line of defense against mutations that inactivate Ink4a, thereby compensating for its loss.22

In contrast, the remaining Ink4 family members, p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d are composed of five rather than four ankyrin repeats, are encoded by genes located on other chromosomes, and share less amino acid sequence homology with p16Ink4a, p15Ink4b or with each other.13–15 The Ink4c and Ink4d genes are highly and ubiquitously expressed in stereotypic patterns during organismal development, and their loss of function is associated with specific abnormalities that affect different tissues.16,23–28 Inactivation of Ink4c predisposes to tumor development, but, perhaps paradoxically, Ink4d has not been revealed to have any tumor suppressive function.29

Although the spatial and temporal patterns of expression of the Ink4 genes have been characterized in detail, post-transcriptional regulation of the Ink4 proteins has been less well studied. Both p16Ink4a and p15Ink4b are highly stable proteins.30–32 Proteasomal degradation of p16Ink4a has been reported to be either ubiq-uitin-dependent, due to its N-terminal polyubiquitination,33 or ubiquitin-independent, through its direct binding to the 11S proteasomal lid REGγ/PA28γ.34 In human mammary epithelial cells, the half-life of p15Ink4b is 8.5 hours; however, in response to cellular stimulation by the anti-proliferative cytokine, transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), the half-life of p15Ink4b is extended to 34 hours, thereby enhancing cell cycle arrest.32 Expression of p18Ink4c protein increases in differentiating versus proliferating oligodendrocytes without overt changes in its mRNA levels,35 implying that post-transcriptional mechanisms play the dominant role in regulating protein abundance. However, there is evidence that the turnover of p19Ink4d is more dynamic than that of the other Ink4 proteins. In proliferating cells, p19Ink4d levels oscillate throughout the cell cycle with the lowest levels observed in G1 phase and the highest in late S and G2 phases.14,36 In G1 phase, Ink4d mRNA is nonabundant and the protein is subjected to rapid ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation, while in S and G2 phases, Ink4d mRNA levels rise and the rate of protein turnover is coordinately diminished. Here we show that p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d protein levels are not only differentially regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, but are subject to completely opposite modes of regulation when associated with their target Cdks. These differences point to a greater degree of functional complexity than previously suspected.

Results

Expression of p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d is differentially regulated

The synthesis of both mouse and human Ink4d mRNAs and their encoded p19Ink4d polypeptides are periodically expressed throughout the cell cycle with peak levels of both Ink4d mRNA and protein being achieved during G2/M phase.14,36 In contrast, changes in p18Ink4c protein levels can occur without concurrent alterations in its mRNA expression,35 implying that, unlike p19Ink4d, the abundance of the p18Ink4c protein is more dependent upon its post-transcriptional regulation. We therefore set out to characterize the parameters responsible for the differences in behavior of these two related Ink4 family members.

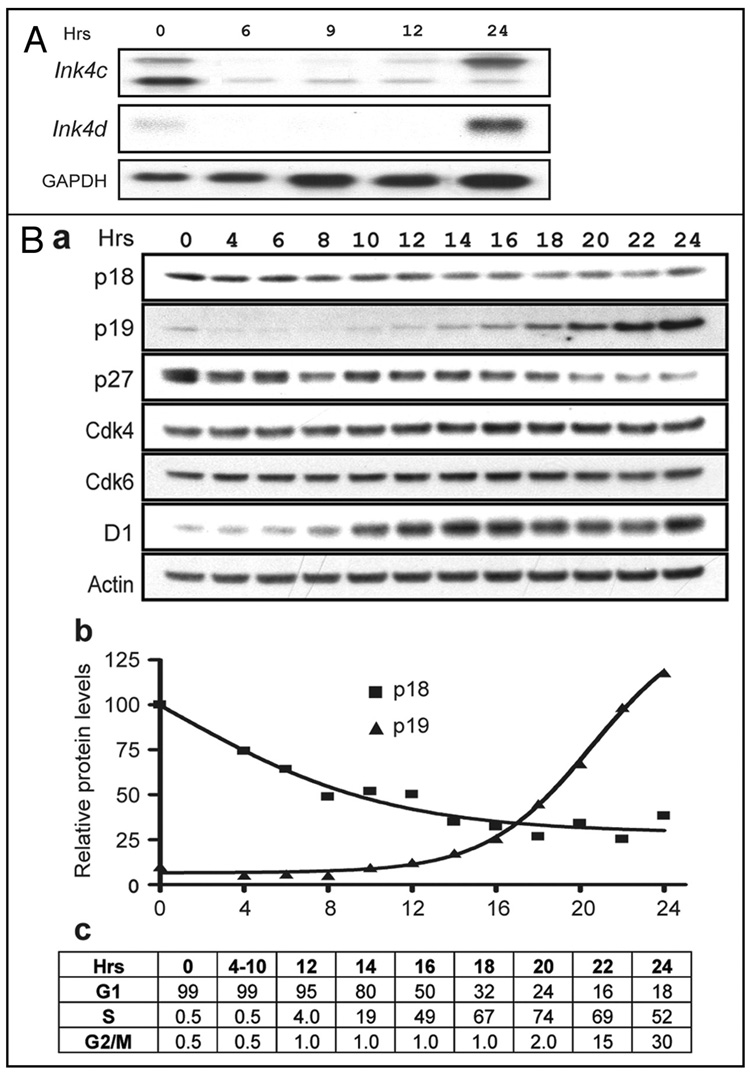

We compared the patterns of Ink4c and Ink4d mRNA and protein expression in cultured mouse NIH-3T3 cells that were made quiescent by serum starvation and then restimulated to synchronously enter the cell cycle. Expression of the Ink4 mRNAs was evaluated by Northern blotting (Fig. 1A), and immunoblotting was used to compare p18Ink4c protein levels to those of p19Ink4d and other cell cycle regulators (Fig. 1B, parts a and b). Progression through the cell cycle was determined by flow cytometric analysis of DNA content in samples harvested at different times after serum stimulation (Fig. 1B, part c).

Figure 1. Dynamics of serum-induced cell cycle entry and progression.

NIH-3T3 cells were made quiescent by contact inhibition and serum starvation and then restimulated to synchronously enter the cell division (A) Ink4c and Ink4d mRNA levels in NIH-3T3 cells were determined by Northern blotting. The positions of the two spliced Ink4c mRNAs of 2.4 and 1.2 Kb are indicated at the left margin and times (Hrs) following serum-stimulation are indicated at the top. (B) (part a) Antibodies directed to the proteins indicated at the left of the panels were used to track their expression by immunoblotting of lysates harvested at different times (Hrs) after cell cycle entry. All lanes contained similar amounts of total protein, and actin (bottom) was used as a loading control. (part b) Plot of the relative levels of expression of p18Ink4c (■) and p19Ink4d (▲) quantified using a scanner. (part c) Cells taken at the indicated times (Hrs) after serum stimulation (top) were stained with propidium iodide and their DNA content was determined by flow cytometry. The fraction of cells in G1 (2N), G2/M (4N) and S (intermediate ploidy) are indicated.

In serum-starved NIH-3T3 cells, two Ink4c spliced mRNA variants of 1.2 kb and 2.4 kb were detected (Fig. 1A); these mRNAs are known to differ in their 5′-untranslated sequences, with the shorter form being more efficiently translated than the longer form.37 Expression of both the 1.2 and 2.4 kb Ink4c RNAs decreased when cells reentered the cell cycle. However, by twenty-four hours after serum restimulation, the longer Ink4c mRNA was again abundantly expressed (Fig. 1A), in agreement with previous findings that the 2.4 kb transcript, as well as the mRNA encoding p19Ink4d, are periodically expressed and are most abundant during the G2/M phase of the cell division cycle.14,36

Although Ink4c mRNAs, while expressed in G0 cells, became difficult to detect by mid-G1 (Fig. 1A), p18Ink4c protein levels declined much more slowly as the cells advanced through G1 and S phase, suggesting that p18Ink4c is a stable protein (Fig. 1B, parts a and b). The relatively low level of p18Ink4c observed by 24 hours after cell cycle re-entry was maintained throughout subsequent cell cycles in asynchronously dividing cells, despite oscillations in the 2.4 kb mRNA. By comparison, p19Ink4d protein levels were low in G0 cells, were barely detectable in G1 phase, but then rose rapidly in late S phase to peak at G2/M (Fig. 1B, parts a and b). There was only a 4-fold overall difference between the maximal and minimal levels of p18Ink4c during the 24 hour period following cell cycle reentry, whereas p19Ink4d expression was significantly more dynamic, increasing at least 20 fold (Fig. 1B, parts a and b) and then declining again as cells entered the next division cycle (data not shown).14 As expected, p27Kip1 levels were highest in serum-starved cells and subsequently decreased.38,39 The cyclin D-dependent catalytic subunits, Cdk4 and Cdk6, which are resistant to inhibition by p27Kip1 (reviewed in ref. 2), were detected in serum-starved cells and throughout the ensuing cell division cycle. By contrast, cyclin D1 was barely expressed in G0 cells but accumulated during G1 phase in response to mitogen stimulation,40 consistent with progressive cyclin D-dependent assembly and allosteric activation of cyclin D1-Cdk holoenzymes as NIH-3T3 cells approach the G1/S boundary.41

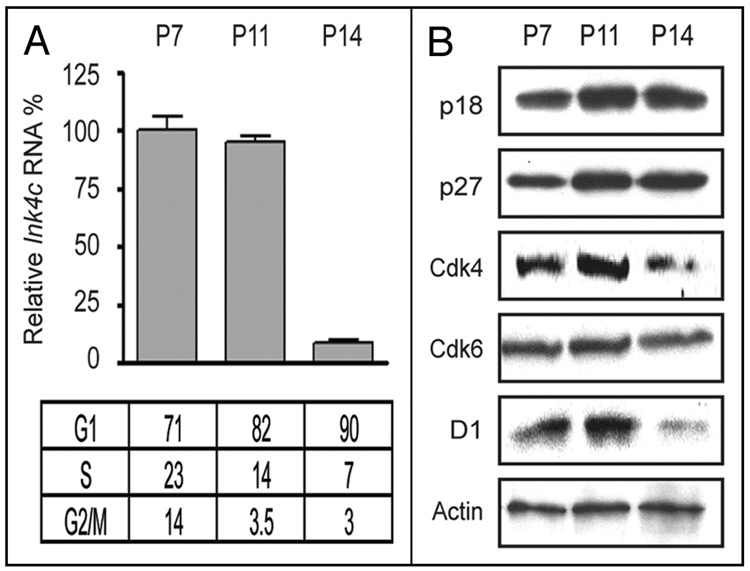

We next turned our attention to primary, proliferating granule neuron progenitors (GNPs) purified from the cerebella of wild type C57BL/6 mice at different days after birth. Unlike other organs, the cerebellum is largely formed in neonatal animals, primarily reflecting the massive proliferation of GNPs, which is maximal at postnatal day-5 (P5) and declines thereafter as GNPs exit the division cycle and differentiate. In the mouse, formation of the cerebellum is largely complete by P30. Previous studies indicated that Ink4c mRNA is expressed as GNPs in the external germinal layer of the developing cerebellum exit the division cycle.42 Indeed, Ink4c mRNA was expressed at postnatal day 7 (P7) and at P11, but was extinguished by P14, a time when most of the cells have become postmitotic (Fig. 2A). In contrast, p18Ink4c protein levels remained high at P14 (Fig. 2B) despite the absence of its mRNA, again implying that p18Ink4c is a stable protein. The overall levels of other cell cycle regulators including cyclin D1 and Cdk4 were decreased by P14, whereas, like p18Ink4c, p27Kip1 protein expression increased at P11 and P14, again consistent with the progressive accumulation of post-mitotic granule neurons. Interestingly, although p27Kip1 expression is maintained in mature granule neurons throughout life, p18Ink4c protein is not detected by P28 (negative data not shown). In contrast, Ink4d is not expressed in GNPs, even though it is continually synthesized in cortical neurons elsewhere in the brain.23,25

Figure 2. Expression of Ink4c and other cell cycle regulators in cerebellar GNPs.

(A) RNA was extracted from primary GNPs purified from the developing cerebella of postnatal (P) mice at 7, 11 and 14 days after birth (indicated at the top of the panel), and quantitative real time PCR was used to quantify the relative level of expression of Ink4c RNA in the three samples. Cells stained with propidium iodide were examined by flow cytometry to estimate their DNA content, and the fraction of cells in different phases of the cell cycle is indicated at the bottom. (B) Antibodies directed to the proteins indicated to the left of the panels were used to quantify their expression in GNPs purified at the indicated days after birth.

p18Ink4c is polyubiquitinated in vitro

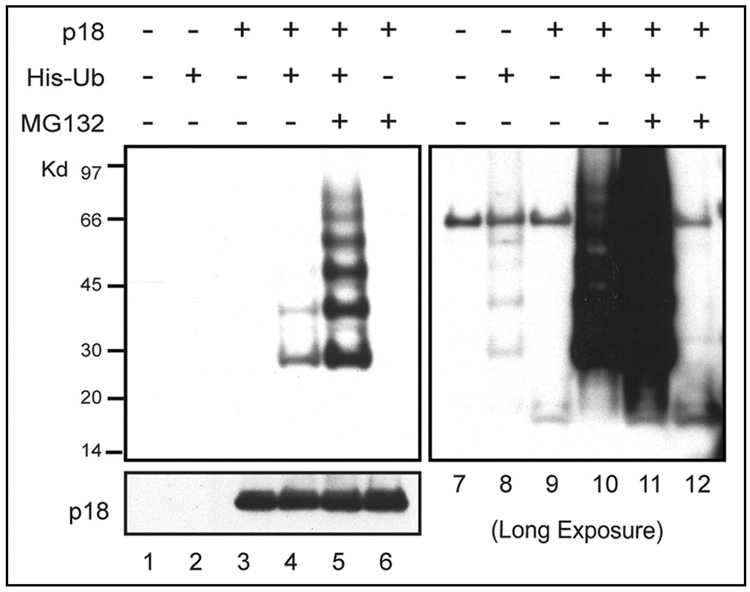

We next evaluated whether the turnover of p18Ink4c depends on the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. To this end, we enforced the expression of p18Ink4c in human 293T cells together with a vector expressing ubiquitin (Ub) tagged with six tandem histidine residues (His6) at the N-terminus. Two days after transfection, cells were either left untreated or were exposed to the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 12 hours prior to their harvest. Cell pellets were lysed in buffer containing 8 M urea to inhibit the activity of de-ubiquitinating enzymes, and His6-tagged ubiquitinated protein species were recovered with nickel agarose beads, electrophoretically separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels, and blotted with antibodies to p18Ink4c. We observed a ladder of polyubiquitinated p18Ink4c forms, the intensity of which was significantly increased after treatment of the cells with MG132 (Fig. 3, left, lanes 4 and 5). Equivalent levels of enforced p18Ink4c protein expression in the transfected cells were confirmed by immunoblotting (bottom, lanes 3–6). A longer exposure of the same blot also revealed the presence of very low levels of the endogenous polyubiquitinated human p18Ink4c species (Fig. 3, right, lane 8). Thus, both exogenously expressed and endogenous p18Ink4c undergo polyubiquitination.

Figure 3. Polyubiquitination of p18Ink4c.

Human 293T cells were cotransfected with vectors encoding His-tagged ubiquitin and/or p18Ink4c as indicated above the panels. 48 hrs after transfection, cells were treated with MG132 or solvent for 12 hrs and harvested. Ubiquitinated proteins were recovered from denatured cell lysates by affinity chromatography on Ni-agarose beads, and proteins electrophoretically separated on denaturing gels were blotted with antibodies to p18Ink4c. Expression of p18Ink4c in unfractionated cell lysates is indicated in the bottom panel (lanes 1–6). A longer exposure of the same immunoblot is shown at the right (lanes 7–12) in order to document the significantly lower level of polyubiquitination of endogenous human p18INK4C recovered from the same cells (lane 2 and 8).

Lysines 46 and 112 are the major acceptors of polyubiquitin chains in p18Ink4c

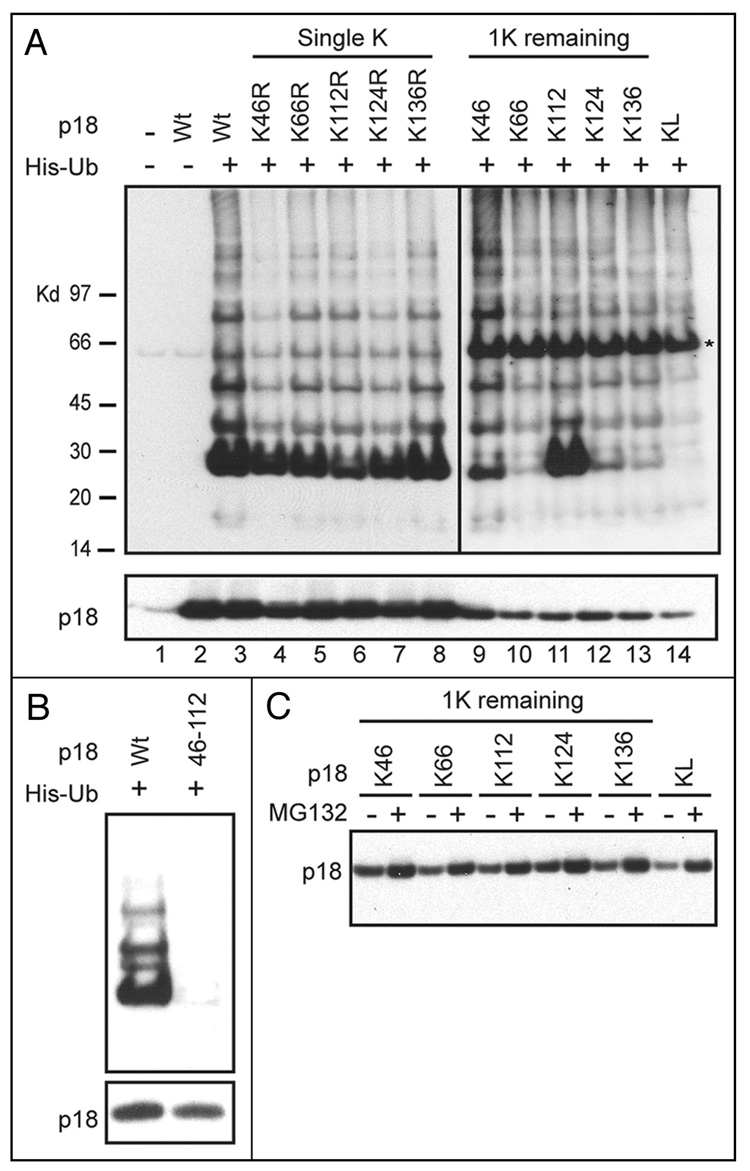

Covalent attachment of Ub to target proteins generally occurs on internal lysine residues,43 although Ub conjugation to the N-termini of proteins can also occur.44 Mouse p18Ink4c contains five lysine residues at positions 46, 66, 112, 124 and 136. All of these lysines have cognates in human p18INK4c, but these specific residues are not conserved in the other three human INK4 family members.9 To identify the lysine residues in p18Ink4c that can be conjugated by Ub, we mutated each of the five lysines individually (“single K” mutants); eliminated four of the five lysines leaving only one intact (“1K remaining”); and generated a lysine-less mutant (KL). Lysines were substituted by arginines so as to maintain basic residues at each position.

cDNAs encoding p18Ink4c mutants in pcDNA3 expression vectors were transfected with His6-Ub into 293T cells, and ubiquitinated proteins were evaluated after affinity purification. Analysis of single K mutants demonstrated that p18Ink4c ubiquitination was not restricted to a unique lysine residue, since none of the individual arginine for lysine substitutions abolished p18Ink4c ubiquitination (Fig. 4A, lanes 4–8). Immunoblotting of the unfractionated lysates with antibodies to p18Ink4c confirmed that similar levels of the wild type and mutated proteins were expressed following transfection (Fig. 4A, bottom, lanes 2–8). In turn, the ubiquitination profiles obtained with mutants retaining only a single lysine further revealed that each could be polyubiquitinated to some extent (Fig. 4A, lanes 9–13). Despite the fact that the transfection conditions for vectors expressing the mutants with only 1K remaining were identical to those used to express the single K to R substitutions, significantly lower levels of mutant p18Ink4c proteins were achieved (Fig. 4A, bottom, lanes 9–13, and see below). This necessitated longer exposure of the immunoblot to visualize polyubiquitin ladders (Fig. 4A, top, lanes 9–14). Using this series of mutants, lysines 46 and 112 appeared to represent the major Ub acceptors based on the relative efficiencies of conjugation (lanes 9 and 11). Notably, retention of K112 seemed to favor monoubiquitination (lane 11), whereas ladders formed on K46 were more uniform (lane 9). In agreement with these findings, ubiquitination of p18Ink4c was almost completely abolished when lysines 46 and 112 were both eliminated (Fig. 4B). Substitution of all five lysines to arginines (p18Ink4c-KL) also reduced detection of polyubiquitinated species (Fig. 4A, lane 14). The faint residual ladder detected after relatively long exposure of the latter blot corresponds in intensity to the signal emanating from endogenous human p18INK4C (compare Fig. 4A, lane 14 to Fig. 3, lane 8); however, we cannot formally exclude that the KL mutant is ubiquitinated at a low level at its N-terminus. Together, these findings indicate that lysines 46 and 112 are the preferred acceptors for Ub conjugation.

Figure 4. Lysines 46 and 112 of p18Ink4c are major targets of ubiquitination conjugation.

(A) Vectors encoding wild type (Wt) p18Ink4c or different Ink4c mutants and His-tagged ubiquitin were co-transfected into human 293T cells (as indicated at the top of the panels). 48 hrs post-transfection, cells were harvested and affinity-purified. Ubiquitinated proteins were recovered, separated, and detected by immunoblotting as in Figure 3. As described in the text, “single K” mutants contained unique lysine to arginine substitutions, whereas “1K remaining” mutants contained only the single lysine indicated with the other four mutated to arginine. A lysine-less (KL) mutant lacking all five lysine residues was similarly analyzed. (B) Vectors encoding Wt p18Ink4c or a double mutant lacking lysines 46 and 112 were analyzed as in (A). The relative levels of p18Ink4c expression in unfractionated cell lysates are indicated at the bottom. (C) Cells expressing the indicated mutants were treated with MG132 or with solvent alone, and the levels of p18Ink4c in unfractionated cell lysates were determined by immunoblotting. Equal quantities of total protein were loaded in each lane of the gel.

Although our naïve prediction was that elimination of ubiquitination by lysine mutagenesis would further stabilize p18Ink4c, all mutants that retained only single lysine residues were instead expressed at lower levels than the single K or wild type proteins (Fig. 4A, lower, lanes 9–13). Elimination of both lysines 46 and 112, while greatly attenuating ubiquitination, was similarly unaccompanied by increased p18Ink4c expression (Fig. 4B), while, paradoxically, the lysine-less mutant was the least able to accumulate following transfection (Fig. 4A, bottom, lane 14). When cells expressing these mutants were treated with MG132, inhibition of the proteasome led to their further stabilization, arguing that even the lysine-less mutant remained subject to proteasomal degradation (Fig. 4C). Studies with the related family member, p16INK4A, have indicated that most, if not all, cancer-associated point mutations that are distributed widely throughout the polypeptide inactivate its tumor suppressive function by triggering its misfolding and proteasomal degradation.45 Mutants in p18Ink4c can also affect its proper folding and stability,46 so we suspect that the arginine for lysine substitutions accelerate the degradation of misfolded species in the proteasome, possibly through an Ub-independent pathway.

Kinetics of p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d turnover

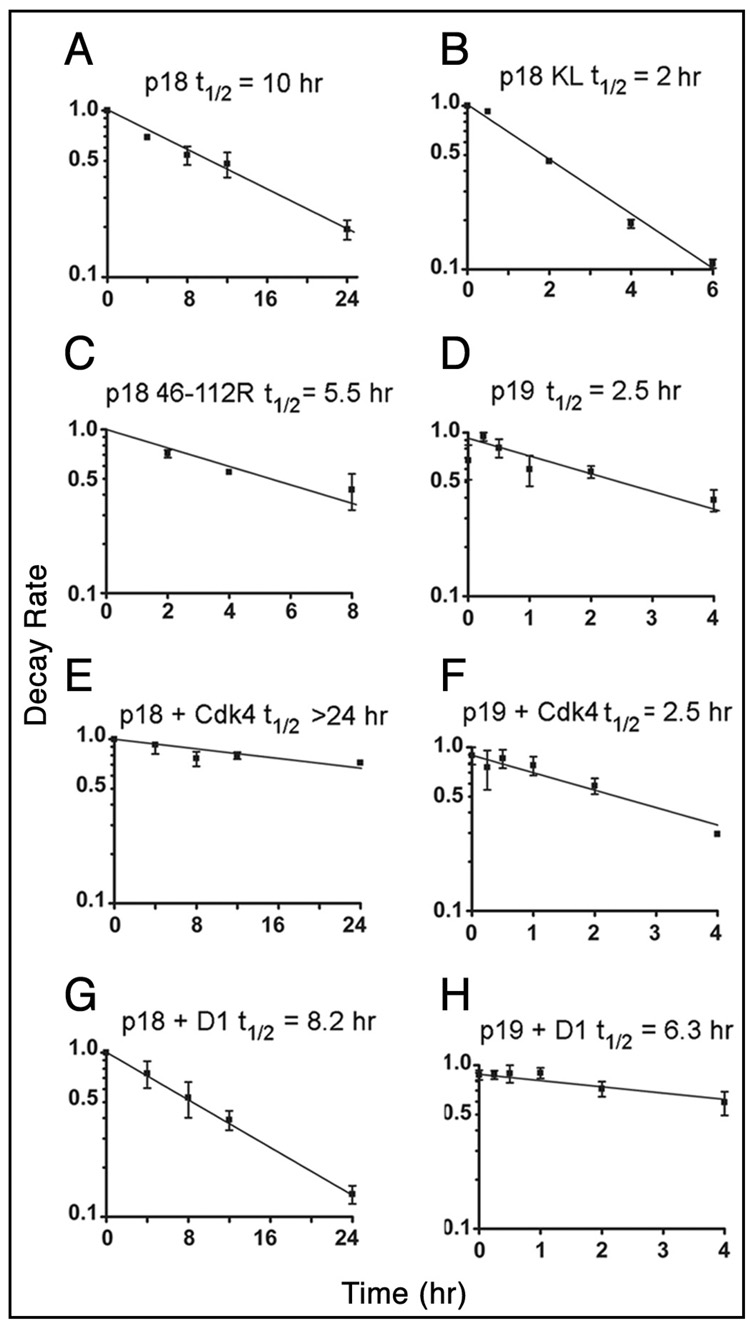

Although, the half-life of p18Ink4c is recognized to be >4 hours,36 it has not been precisely determined. To characterize the rate of turnover of wild type p18Ink4c and selected lysine mutants, 293T cells expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged p18Ink4c were metabolically labeled for 2 hours with [35S]-methionine 48 hours after transfection. Cells transferred to radiolabel-free medium containing a >100-fold excess of unlabelled methionine were harvested at different times over the ensuing 24 hour period, and p18Ink4c precipitated with antibodies to the HA-tag was resolved on denaturing gels and detected by autoradiography. In 293T cells, the half-life of HA-tagged wild type p18Ink4c was 10 hours (Fig. 5A), which was identical to the half-life of the endogenous p18Ink4c protein expressed in NIH-3T3 cells (data not shown). In contrast, the half-life of the HA-tagged p18Ink4c-KL mutant expressed in 293T cells was only 2 hours (Fig. 5B), whereas the K46R-112R double mutant exhibited an intermediate turnover rate of 5.5 hrs (Fig. 5C). These results directly confirm that the arginine for lysine substitutions in p18Ink4c that limit its polyubiquitination nonetheless destabilize the protein.

Figure 5. Kinetic analyses of Ink4 protein turnover.

Transfected human 293T cells expressing HA-tagged wild type p18Ink4c (A) or either of two indicated HA-tagged p18Ink4c mutants (B and C) were metabolically labeled with [35S]-methionine for 2 hrs and “chased” for the indicated times with isotope-free medium. Proteins precipitated with antibodies to the HA epitope were electrophoretically separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels, transferred to a membrane, and detected by autoradiography. The rate of turnover of p18Ink4c was quantified by scanning the autoradiograms. (D) 293T cells expressing p19Ink4d were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit protein synthesis. Cells were harvested at the indicated times after drug treatment, and the levels of p19Ink4d were determined by immunoblotting of whole cell lysates and scanning of the images. Wild type Cdk4 or Cyclin D1 were co-expressed with p18Ink4c (E and G) or with p19Ink4d (F and H) in human 293T cells and the half-lives of p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d were determined as above by kinetic “pulse-chase” analysis. Error bars in all panels indicate the standard deviations of the means for triplicate determinations; lines were fit by regression analysis using Graph Pad Prism 4 software.

Because lysine-less p16Ink4a can be degraded by the REGγ/PA28γ proteasome,34 we compared the levels of endogenous p18Ink4c in immortalized mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from wild type mice and from those in which the gene encoding REGγ had been disrupted.47 In turn, we transfected 293T cells with expression vectors encoding both p18Ink4c and REGγ. In each case, we saw no differences in p18Ink4c expression, implying that the polyubiquitinated wild-type protein is not detectably degraded by the REGγ-capped proteasome (negative data not shown).

Unlike p18Ink4c, p19Ink4d was reported to have a short half-life.36 We therefore characterized the turnover of endogenous p19Ink4d in NIH-3T3 cells and of exogenously expressed p19Ink4d in 293T cells in the presence of cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis. We found that exogenously expressed p19Ink4d had a half-life of 2.5 hours (Fig. 5D), equivalent to that of the endogenous protein (data not shown). These results confirm that p19Ink4d has a much shorter half-life than p18Ink4c, consistent with their differential regulation in NIH-3T3 cells (Fig. 1).14

Interactions of p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d with Cdk4 differentially affect their ubiquitination and stability

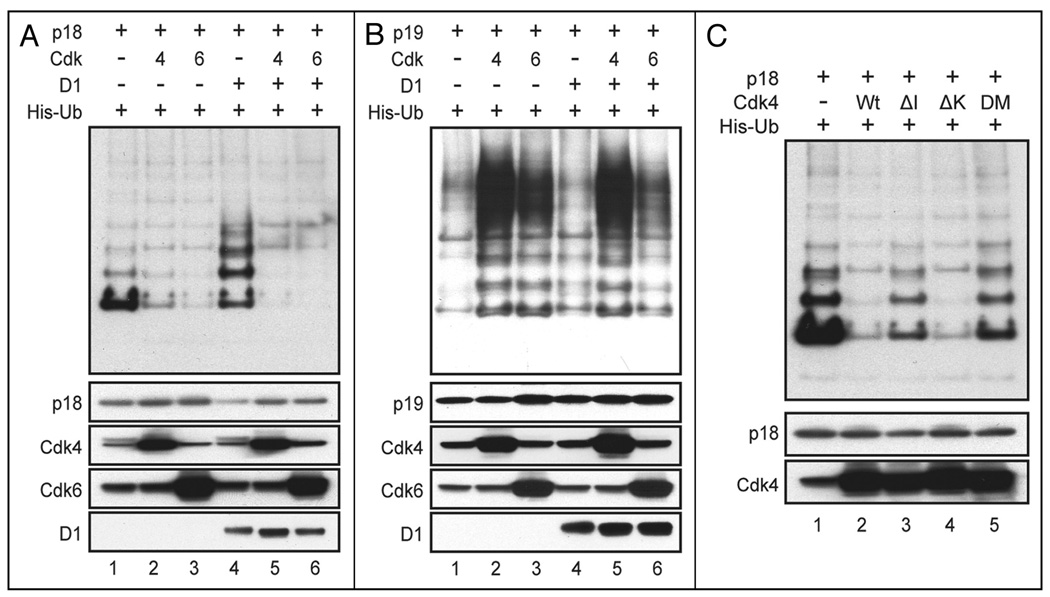

Binding of p19Ink4d to Cdk4 increases its polyubiquitination and turnover; in turn, competition for Cdk4 binding by cyclin D1 can abolish Cdk4-dependent p19Ink4d ubiquitination and stabilize the protein.36 We therefore addressed whether the polyubiquitination and turnover of p18Ink4c would similarly be increased through interactions with Cdk4 and Cdk6. We performed parallel ubiquitination assays for p19Ink4d and p18Ink4c in 293T cells in the presence or absence of overexpressed Cdk4, Cdk6 and/or cyclin D1. Surprisingly, ubiquitination of p18Ink4c was reduced when the protein was coexpressed with Cdk4 or Cdk6 (Fig. 6A, top, lanes 2 and 3 versus lane 1), but was increased when p18Ink4c was coexpressed with cyclin D1 alone (Fig. 6A, top, lane 4). When cyclin D1 was coexpressed with Cdk4 or Cdk6, p18Ink4c polyubiquitination was again limited (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 5 and 6 with lanes 2 and 3). Immunoblotting of the cell lysates confirmed that Cdk4, Cdk6 and cyclin D1 were overexpressed (Fig. 6A, lower). Importantly, reduced levels of p18Ink4c protein correlated with its polyubiquitination (lanes 1 and 4 versus other lanes).

Figure 6. Effects of Cdk and cyclin D1 coexpression on the polyubiquitination and accumulation of Ink4 proteins.

Cells transfected with expression plasmids encoding proteins indicated at the top left of each panel together with a plasmid encoding His-Ub were lysed in urea-containing buffer, and covalently His-Ub-tagged proteins recovered by affinity chromatography were separated on denaturing gels and blotted with antibodies to either p18Ink4c (A and C) or p19Ink4d (B). The relative levels of the different proteins (indicated at the bottom) expressed in unfractionated cell lysates are also shown. Equal quantities of total protein were loaded and electrophoretically separated in all lanes. The Cdk4 mutants used for the experiment in (C) included one that is not bound or inhibited by Ink4 proteins (ΔI), one that is catalytically inactive (ΔK), and a double mutant (DM) containing both mutations.

These results were in striking contrast with those reported for p19Ink4d. Indeed, we reproduced the previously described enhancement of p19Ink4d ubiquitination in the presence of overexpressed Cdk4 or Cdk6 (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 and 3 versus lane 1).36 Enforced expression of cyclin D1 did not detectably limit the polyubiquitination of p19Ink4d when it was coexpressed with Cdk4 (Fig. 6B, top, compare lanes 5 and 2) but did reduce p19Ink4d polyubiquitination in the presence of Cdk6 (compare lanes 6 and 3). Under these experimental conditions, we were unable to correlate the net levels of p19Ink4d with its degree of ubiquitination (Fig. 6B, lower).

To test whether the Cdk4-mediated inhibition of p18Ink4c polyubiquitination depended on Cdk4 kinase activity or simply on its association with Cdk4, we used three missense point mutants of Cdk4. These included Cdk4-R24C (or ΔI) which is unable to interact with Ink4 proteins,48,49 Cdk4-D158N (or ΔK) that is devoid of kinase activity,48 and a double-mutant, Cdk4-R24C/D158N (or DM) that is defective for both properties (Fig. 6C). Whereas Cdk4-ΔI and Cdk4-DM were unable to affect the levels of ubiquitination of p18Ink4c (Fig. 6C, top, lanes 3 and 5), Cdk4-ΔK, like the wild type catalytic subunit, was able to do so (Fig. 5C, top, lanes 2 and 4). Thus, the ability of Cdk4 to inhibit p18Ink4c polyubiquitination depends upon its ability to bind p18Ink4c but not on Cdk4 kinase activity. Similar results were observed with the corresponding double mutant of Cdk6 (R31C, D163N) (data not shown).

Because the interaction of the two Ink4 proteins with Cdk4/6 and Cyclin D1 had opposite effects, polyubiquitination of p19Ink4d and p18Ink4c must be regulated by different mechanisms. We therefore analyzed the effect of Cdk4 or Cyclin D1 overexpression on the turnover of p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d in an attempt to link their propensity to undergo ubiquitination with their stability. When Cdk4 was co-expressed with p18Ink4c in 293T cells, the half-life of p18Ink4c was increased (p < 0.04) more than threefold (Fig. 5E versus A). Therefore, Cdk4-mediated interference of p18Ink4c ubiquitination can stabilize the protein. In contrast, Cdk4 had no significant effect on the already rapid turnover of p19Ink4d (Fig. 5F versus D). In turn, when p18Ink4c was co-expressed with cyclin D1, its half-life slightly decreased to ~8 hours (Fig. 5G versus A), whereas the half life of p19Ink4d more than doubled (p < 0.04) (Fig. 5H versus D). Thus, the ubiquitination and stabilities of p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d are regulated in an opposite manner through interactions with their Cdk targets.

Discussion

Progression through the cell division cycle requires an appropriate balance between the expression of both positive (Cyclin-Cdks) and negative (Cdk inhibitors) regulators, the activities of which are governed by both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Although cells in G1 phase are highly attuned to their extracellular environment and are regulated through receptor-mediated signals, cells that enter S phase are committed to completing the division cycle, and their further progression is largely governed by cell-autonomous feed forward and feedback mechanisms. In order for proliferating cells to execute these functions properly, the key regulators of the division cycle must oscillate dynamically and be expressed with defined periodicities that are coordinated with the cell’s position in the cycle.50 It logically follows that stably elevated expression of a Cdk inhibitor would be incompatible with cell cycle progression and might instead prove important for cell cycle entry or exit, and for maintaining differentiated cells in a quiescent, post-mitotic state.

Three of the four Ink4 proteins are stably expressed. Whereas p16Ink4a and p15Ink4b act to inhibit the cell cycle in response to various forms of oncogenic stress, p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d are engaged in regulating various aspects of organismal development.24–28,42 Notably, inactivation of the Ink4a and Ink4b genes, while predisposing to tumor formation, leads to no overt developmental abnormalities, whereas mice lacking Ink4c exhibit organomegally and focal developmental defects affecting male germ cells, the kidney, and various endocrine organs.24,26,27 Our findings indicate that, like p16Ink4a and p15Ink4b, p18Ink4c is a highly stable protein whose temporal decay during cell cycle entry of cultured NIH-3T3 cells on the one hand and increased expression in primary cerebellar granule neuron precursors exiting the cycle on the other are largely determined by post-transcriptional mechanisms involving the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Unlike the other Ink4 family members, p19Ink4d is an outlier, as it is an unstable protein whose levels dynamically oscillate as much as 20-fold, peaking late in the cycle as cells approach mitosis and decreasing again as they reenter an ensuing G1 phase.14,36 p19Ink4d is the only Ink4 protein to have been implicated in DNA repair and cell survival after UV irradiation.51,52 Its short half life would be advantageous for regulating transient processes by allowing easy clearance of the protein once its activity is no longer needed. Notably, of the four Ink4 proteins, only p19Ink4d lacks a tumor suppressive function, implying that its ephemeral expression may be incompatible with such a role. In turn, the predisposition to cancer development associated with inactivation of the other three family members is likely linked to their regulation of cell cycle entry and exit rather than progression through the division cycle per se or acute checkpoint responses.

Based on experiments in which single or multiple lysine residues within p18Ink4c were mutated to arginines, we were able to conclude that its ubiquitination occurs mainly on lysine residues 46 and 112. A double mutant lacking only these two lysines was found to be essentially devoid of ubiquitin, despite the fact that all internal lysines could act as ubiquitin acceptors at some level. The formation of ubiquitination ladders observed with p18Ink4c proteins containing only single lysine residues also revealed that, despite the possibility of its multi-monoubiquitination, p18Ink4c undergoes polyubiquitination, a process required for proteasomal recognition and consistent with the observed accumulation of p18Ink4c in the face of proteasome inhibition.53 We therefore expected that mutants of p18Ink4c that lacked lysines 46 and 112 would be degraded more slowly than their wild type counterpart. However, this was not the case, as all such mutants had reduced half-lives and accumulated to comparatively reduced levels following their enforced expression. Similar findings have been made with p16Ink4a, which can sustain inactivating mutations that are widely distributed throughout the molecule. Regardless of the many codons so affected, these mutations disrupt the folding of ankyrin repeats, destabilizing the protein and accelerating its turnover.45 We reason, then, that arginine to lysine substitutions within p18Ink4c similarly subvert its proper folding.46 Given that the lysine-less p18Ink4c mutant proved to be highly unstable despite its lack of polyubiquitination and yet accumulated in response to proteasomal inhibition, the turnover of misfolded p18Ink4c variants likely occurs through an ubiquitin-independent pathway.

The ubiquitination and turnover of p18Ink4c were significantly retarded in response to the enforced co-expression of Cdks. This effect depended on the ability of Cdks to bind to p18Ink4c but did not require Cdk enzymatic activity. The enforced expression of cyclin D1 had the opposite effect, increasing p18Ink4c polyubiquitination and turnover and overcoming the effects of Cdks. This is consistent with observations that Ink4 proteins and D-type cyclins respectively exert their anti- and pro-proliferative effects by competing with one another in forming binary complexes with their targeted Cdks.2,7,54 Competition between D-type cyclins and p18Ink4c for binding to Cdks may well explain how p18Ink4c expression is maintained for many days in the absence of new Ink4c mRNA synthesis during postnatal cerebellar development. The degradation of D-type cyclins as GNPs exit the cell cycle should favor maintenance of inhibitory p18Ink4c-Cdk4/6 complexes during the period in which GNPs migrate to their final positions and establish neuronal connections in the cerebellum. An analogous mechanism leading to stabilization of p15Ink4b-Cdk complexes in response to TGFβ signaling12,32 implies that regulation of Ink4 protein turnover in response to environmental cues may be a general feature underlying a variety of anti-proliferative and differentiative processes.

Surprisingly, these findings with p18Ink4c directly contrast with what occurs with p19Ink4d, whose polyubiquitination was instead reported to be increased by Cdk binding and decreased in the presence of cyclin D1.36 We confirmed that polyubiquitination of p19Ink4d was increased in response to Cdk coexpression, although in our hands, we did not detect statistically significant effects of Cdks on its already rapid rate of turnover. Enforced expression of cyclin D1 almost doubled the stability of p19Ink4d (p < 0.05). How can these diametrically opposed responses to p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d ubiquitination in the presence of Cdks and D-type cyclins be explained? The structures of both p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d have been solved in complexes with Cdk6.8,10 Lysine 62, the principle ubiquitin acceptor within p19Ink4d,36 is exposed at the surface of the p19Ink4d-Cdk6 complex, whereas lysine 46 in p18Ink4c lies buried within the p18Ink4c-Cdk6 interface. Thus, it seems more likely that p19Ink4d can be ubiquitinated when complexed to Cdk6, whereas ubiquitination of lysine 46 and possibly lysine 112 of p18Ink4c should be sterically hindered. If so, ubiquitination of the unbound form of p18Ink4c may be favored, consistent with the interpretation that competitive dissociation of the complex by cyclin D1 accelerates p18Ink4c ubiquitination and degradation. Overall, these differences in protein turnover help explain why, despite very similar mRNA expression profiles, p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d proteins play very different biological roles.

Materials and Methods

Expression plasmids

Ink4c point mutants in which individual or multiple lysine residues were substituted by arginine were generated by a two-step PCR method using a pBluescript plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) containing mouse Ink4c cDNA as template.14 For the first step, the reaction mix of 50 µL included Ink4c cDNA (100 ng), 25 pmol primers (either the complementary sense or anti-sense primers encoding lysine to arginine mutation in combination with T3 or T7 primer, respectively), 200 µM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Pfu turbo in Pfu buffer (Stratagene). The reaction mix was subjected to 34 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 95°C, 1 min annealing at 52°C, and 2 min extension at 72°C. PCR products were gel-purified, and T3-sense and T7-anti-sense product pairs were mixed with T3 and T7 primers for a second PCR reaction consisting of 15 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 95°C, 1 min annealing at 37°C, and 2 min extension at 72°C, followed by 34 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 95°C, 1 min annealing at 52°C, and 2 min extension at 72°C. The final PCR products were gel-purified, digested with BamHI and EcoRI, and cloned into pCDNA3.1+ (V790-20, Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA) or an MSCV-IRES-GFP retroviral vector,55 based on the mouse stem cell virus (MSCV) and containing an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) that allows translation of green fluorescent protein (GFP). To convert lysine to arginine (underlined codons) primers were designed to include 12 complementary bases on the 5′ and 3′ sides of the lysine codon as follows: K46R: 5′-CTG CAG GTT ATG AGG CTT GGA AAT CCG (sense) and 5′-CGG ATT TCC AAG CCT CAT AAC CTG CAG (anti-sense); K66R: 5′-AAT CCC AAT TTG AGG GAT GGA ACT GGT (sense) and 5′-ACC AGT TCC ATC CCT CAA ATT GGG ATT (anti-sense); K112R: 5′-CAC TTG GCT GCC AGG GAA GGC CAC CTC (sense) and 5′-GAG GTG GCC TTC CCT GGC AGC CAA GTG (anti-sense); K124R: 5′-GAG TTC CTT ATG AGG CAC ACA GCC TGC (sense) and 5′-GCA GGC TGT GTG CCT CAT AAG GAA CTC (anti-sense); K136R: 5′-CAT CGG AAC CAT AGG GGG GAC ACC GCC (sense) and 5′-GGC GGT GTC CCC CCT ATG GTT CCG ATG (anti-sense).

Cdk4 and Cdk6 mutants were generated using the same approach as that described above using the following primers: Cdk4 R24C, 5′-GTG TAC AAA GCC TGC GAT CCC CAC AGT (sense) and 5′-ACT GTG GGG ATC GCA GGC TTT GTA CAC (anti-sense); Cdk4 D158N, 5′-GTC AAG CTG GCT AAC TTT GGC CTA GCT (sense) and 5′-AGC TAA GCC AAA GTT AGC CAG CTT GAC (anti-sense); Cdk6 R31C, 5′-GTG TTC AAG GCC TGC GAC CTG AAG AAC (sense) and 5′-GTT CTT CAG GTC GCA GGC CTT GAA CAC (anti-sense); Cdk6 D163N, 5′-ATA AAG CTG GCT AA CTT TGG CCT TGCC (sense) and 5′-GGC AAG GCC AAA GTT AGC CAG CTT TAT (anti-sense); Wild type Ink4c and a lysine-less (KL) variant tagged with a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope at their C-terminus were synthesized by PCR using 5′-GAA TTC AAG CGT AGT CTG GGA CGT CGT ATG GGT ACT GCA GGC TTG TGG CTC CCCC ( anti-sense) and a T7 primer. PCR products were first cloned into pCR2.1 (TOPO TA cloning kit K450001, Invitrogen), and then the BamHI-EcoRI fragment was cloned into the MSCV-IRES-GFP vector. The identities of all mutations were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. A vector expressing ubiquitin (Ub) tagged with six tandem histidine residues (His6) at the N-terminus56 was provided by Dr. Dick Bohmann (University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry).

Cell culture and cell cycle analysis

Mouse NIH-3T3 fibroblasts and human kidney 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modification of Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Waltham MA), 4 mM glutamine, and 100 units each of penicillin and streptomycin (Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA) in an 8% humidified incubator. MG132 (474790, Calbiochem EMD, Gibbstown, NJ) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxazole (DMSO) prior to its addition to the culture medium at 10 µM final concentration. Primary cerebellar granule neuron progenitors (GNPs) were purified from the cerebella of 7, 11 and 14 day old C57BL/6 mice and lysed immediately after purification without any culture steps, as previously described.42

To achieve synchronous entry into the cell cycle from quiescence (G0), NIH-3T3 cells were maintained at confluence for 48 hrs and serum-starved for 24 hrs in starvation medium [(DMEM with 0.1% FBS and 400 µg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA)]. Cells were then trypsinized and seeded at sub-confluence (1 × 106 cells in 10 cm dishes) in complete serum-containing medium to allow them to reenter into and progress through the cell division cycle. To check for synchrony, samples were stained with propidium iodide and their DNA content was determined by fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS). MODFIT (Verity Software, Topsham, ME) was used to estimate the fraction of cells in G1 (2N), S or G2/M (4N) phase.

Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested, pelleted and either immediately frozen in dry ice and kept at −80°C for later analysis or directly lysed. Lysis was performed with RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 1.0% Nonidet-P40 (NP40), 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)] containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.2 U of Aprotinin per mL, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium fluoride (NaF), and 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4). Protein concentration was quantified by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford IL), and samples were electrophoretically separated on 4%–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen), transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica MA) and detected using antibodies to p18Ink4c (39–3400, Zymed, S. San Francisco CA), p19Ink4d (39–3100, Zymed), Cdk4 (sc-260), Cdk6 (sc-177), Cyclin D1 (sc-450), Actin (sc1615) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and p27Kip1 (610242, BD Transduction Lab, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

In vivo ubiquitination assays

293T cells were cotransfected with 3 µg of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven His6-ubiquitin plasmid56 together with 1.5 µg of Ink4c, Cdk4, Cdk6 and/or cyclin D1 expression plasmids (pcDNA3.1+ backbone) using Fugene-6 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells treated 48 h post-transfection with either 10 µM MG132 or DMSO for 12 h were harvested in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). 10% of the cell suspension was used for direct p18Ink4c immunoblotting, and the rest was resuspended in urea lysis buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, with 8 M urea, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol) containing 10 mM imidazole and sonicated to reduce viscosity. Protein concentration was assessed with Bradford reagent (BioRad, Hercules CA). Equal amounts of protein (2 to 3 mg) in 1 mL of lysis buffer were added to 50 µL of Ni-NTA beads (QIAGEN, Valencia CA) and rotated for 4 hours at room temperature. Beads were washed with urea lysis buffer containing 20 mM imidazole. His-tagged proteins were eluted once in 75 µL of elution buffer (0.15 M Tris-HCl at pH 6.7, 5% SDS, 30% glycerol, 0.72 M β-mercaptoethanol, 200 mM imidazole) for 30 min at room temperature with shaking. 20 µL of the elution product was then mixed with 5 µL of 4X sample buffer (NP0007, Invitrogen), separated on 4%–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen), transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), and detected with monoclonal antibody to p18Ink4c (39–3400, Zymed ) or p19Ink4d (39–3100 Zymed).

Analysis of protein turnover rates

NIH-3T3 cells or 293T cells transfected with the indicated expression plasmids were rinsed twice with PBS and were preincubated for 30 min with methionine- and cysteine-free DMEM containing 10% dialysed FBS and 4 mM L-glutamine. Cells were metabolically labeled for 2 hrs in the same medium supplemented with 200 µCi/mL of Tran35S-Label (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA), washed with complete medium containing 2 mM cold methionine and cysteine, and again cultured in complete medium. At various times thereafter, cells were harvested, frozen in dry ice, and lysed in 100 µL of denaturing buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 2 mM EDTA and 1% SDS) containing protease inhibitors, boiled for 10 min, and passed through a 21 gauge needle to shear DNA. 900 µL of dilution buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 1% deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS containing protease inhibitors) was added, lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min, and were centrifuged at 20,000 xg at 4°C for 10 min. Proteins were quantified by BCA assay (Pierce) and 200 µg were precipitated either with a rabbit polyclonal p18Ink4c antibody14 and recovered with protein-A Sepharose (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ) or, for epitope-tagged proteins, recovered with HA-agarose beads (A2095, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Beads were washed four times with RIPA buffer, denaturated by heating, separated on 4%–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Dried membranes were coated with EN3HANCE (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA) and subjected to radio-fluorography at −80°C using intensifying screens or using a Kodak storage phosphor screen for 4 to 12 hrs and were subsequently scanned with a Storm 860 scanner (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). To determine the rate of degradation of p19Ink4d, transfected 293T cells were treated 48 hrs later with 10 µM of cycloheximide (C4859, Sigma) for various periods of time and harvested. Lysates prepared as above were separated on 4%–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen), transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore) and protein was detected using antibody to p19Ink4d (39–3100, Zymed).

RNA isolation, RNA blotting and real-time PCR

RNA from NIH-3T3 cells or from Percoll-gradient purified GNPs was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Glyoxylated total RNA (20 µg) extracted from NIH-3T3 cells was separated on a 1.1% agarose gel and transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Biosciences). Prehybridation, hybridation and washing were performed as previously described.14 Quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR) performed with RNA extracted from purified GNPs was performed using a 7900HT Sequence Detection System and the TaqMan One Step PCR MasterMix reagent kit (both from ABI, Branchburg NJ). The primer probe sets for murine Ink4c were: 5′-GCG CTG CAG GTT ATG AAAC (sense), 5′-TTA GCA CCT CTG AGG AGA AGC (anti-sense) and 5′-CCT GGC AAT CTC CGG ATT TCA (TaqMan probe). Triplicate reactions were performed using 100 ng total RNA, 100 nM primers and 50 nM probe in 50 µL reactions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Linda Hendershot, Beatriz Sosa-Pineda and Peter Murray for helpful comments and discussions; Mary Thomas and Allison Williams for comments on the manuscript; Deborah Yons, Shelly Wilkerson and Robert Jenson for technical assistance and mouse husbandry; Richard Ashmun and Ann-Marie Hamilton-Easton for flow cytometric analysis; Dick Bohmann for the His6-ubiquitin plasmid; and Lance Barton for REGγ-null MEFs.

This work was supported in part by NIH grants CA-096832 and CA-071907 (to M.F.R.), Cancer Center Core grant CA-21765, La Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale and the Gephardt Endowed Fellowship Signal Transduction (to O.A.) and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. C.J.S. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Cell Cycle E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/7187

References

- 1.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russo AA, Jeffrey PD, Patten AK, Massagué J, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor bound to the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Nature. 1996;382:325–331. doi: 10.1038/382325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavletich NP. Mechanisms of cyclin-dependent kinase regulation: structures of Cdks, their cyclin activators, and cip and INK4 inhibitors. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:821–828. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimmler M, Wang Y, Mund T, Cilensek Z, Keidel EM, Waddell MB, Jäkel H, Kullmann M, Kriwacki RW, Hengst L. Cdk-inhibitory activity and stability of p27Kip1 are directly regulated by oncogenic tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2007;128:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu I, Sun J, Arnaout A, Kahn H, Hanna W, Narod S, Sun P, Tan CK, Hengst L, Slingerland J. p27 phosphorylation by Src regulates inhibition of cyclin E-Cdk2. Cell. 2007;128:281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruas M, Peters G. The p16INK4a/CDKN2A tumor suppressor and its relatives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:115–177. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo AA, Tong L, Lee JO, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Structural basis for inhibition of dependent kinase Cdk6 by the tumour suppressor p16INK4a. Nature. 1998;395:237–243. doi: 10.1038/26155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkataramani R, Swaminathan K, Marmorstein R. Crystal structure of the CDK4/6 inhibitory protein p18INK4c provides insights into ankyrin-like repeat structure/function and tumor-derived p16INK4 mutations. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 1998;5:74–81. doi: 10.1038/nsb0198-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffrey PD, Tong L, Pavletich NP. Structural basis of inhibition of CDK-cyclin complexes by INK4 inhibitors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3115–3125. doi: 10.1101/gad.851100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serrano M, Hannon GJ, Beach D. A new regulatory motif in cell cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature. 1993;366:704–707. doi: 10.1038/366704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannon GJ, Beach D. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGFβ-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature. 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guan KL, Jenkins CW, Li Y, Nichols MA, Wu X, O’Keefe CL, Matera AG, Xiong Y. Growth suppression by p18, a p16INK4/MTS1- and p14INK4B/MTS2-related CDK6 inhibitor, correlates with wild-type pRb function. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2939–2952. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirai H, Roussel MF, Kato JY, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Novel INK4 proteins, p19 and p18, are specific inhibitors of the cyclin D-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2672–2681. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan FK, Zhang J, Cheng L, Shapiro DN, Winoto A. Identification of human and mouse p19, a novel CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitor with homology to p16ink4. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2682–2688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zindy F, Quelle DE, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Expression of the p16INK4a tumor suppressor versus other INK4 family members during mouse development and aging. Oncogene. 1997;15:203–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, Kovalev GI, Al-Regaiey K, Su L, Sharpless NE. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1299–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janzen V, Forkert R, Fleming HE, Saito Y, Waring MT, Dombkowski DM, Cheng T, DePinho RA, Sharpless NE, Scadden DT. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature. 2006;443:421–426. doi: 10.1038/nature05159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molofsky AV, Slutsky SG, Joseph NM, He S, Pardal R, Krishnamurthy J, Sharpless NE, Morrison SJ. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature. 2006;443:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature05091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krishnamurthy J, Ramsey MR, Ligon KL, Torrice C, Koh A, Bonner-Weir S, Sharpless NE. p16INK4a induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature. 2006;443:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe SW, Cepero E, Evan G. Intrinsic tumour suppression. Nature. 2004;432:307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature03098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krimpenfort P, Ijpenberg A, Song JY, van der Valk M, Nawijn M, Zevenhoven J, Berns A. p15Ink4b is a critical tumour suppressor in the absence of p16Ink4a. Nature. 2007;448:943–946. doi: 10.1038/nature06084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zindy F, Soares H, Herzog KH, Morgan J, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Expression of INK4 inhibitors of cyclin D-dependent kinases during mouse brain development. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:1139–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franklin DS, Godfrey VL, Lee H, Kovalev GI, Schoonhoven R, Chen-Kiang S, Su L, Xiong Y. CDK inhibitors p18INK4c and p27Kip1 mediate two separate pathways to collaboratively suppress pituitary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2899–2911. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zindy F, Cunningham JJ, Sherr CJ, Jogal S, Smeyne RJ, Roussel MF. Postnatal neuronal proliferation in mice lacking Ink4d and Kip1 inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13462–13467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latres E, Malumbres M, Sotillo R, Martín J, Ortega S, Martín-Caballero J, Flores JM, Cordón-Cardo C, Barbacid M. Limited overlapping roles of p15INK4b and p18INK4c cell cycle inhibitors in proliferation and tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2000;19:3496–3506. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zindy F, den Besten W, Chen B, Rehg JE, Latres E, Barbacid M, Pollard JW, Sherr CJ, Cohen PE, Roussel MF. Control of spermatogenesis in mice by the cyclin D-dependent kinase inhibitors p18Ink4c and p19Ink4d. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3244–3255. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.9.3244-3255.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen P, Zindy F, Abdala C, Liu F, Li X, Roussel MF, Segil N. Progressive hearing loss in mice lacking the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Ink4d. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:422–426. doi: 10.1038/ncb976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zindy F, van Deursen J, Grosveld G, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. INK4d-deficient mice are fertile despite testicular atrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:372–378. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.372-378.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parry D, Bates S, Mann DJ, Peters G. Lack of cyclin D-Cdk complexes in Rb-negative cells correlates with high levels of p16INK4/MTS1 tumour suppressor gene product. EMBO J. 1995;14:503–511. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro GI, Park JE, Edwards CD, Mao L, Merlo A, Sidransky D, Ewen ME, Rollins BJ. Multiple mechanisms of p16INK4A inactivation in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1995;55:6200–6209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandhu C, Garbe J, Bhattacharya N, Daksis J, Pan CH, Yaswen P, Koh J, Slingerland JM, Stampfer MR. Transforming growth factor β stabilizes p15INK4B protein, increases p15INK4B-cdk4 complexes, and inhibits cyclin D1-cdk4 association in human mammary epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2458–2467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Saadon R, Fajerman I, Ziv T, Hellman U, Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. The tumor suppressor protein p16INK4a and the human papillomavirus oncoprotein-58 E7 are naturally occurring lysine-less proteins that are degraded by the ubiquitin system. Direct evidence for ubiquitination at the N-terminal residue. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41414–41421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen X, Barton LF, Chi Y, Clurman BE, Roberts JM. Ubiquitin-independent degradation of cell cycle inhibitors by the REGγ proteasome. Mol Cell. 2007;26:843–852. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tokumoto YM, Apperly JA, Gao FB, Raff MC. Posttranscriptional regulation of p18 and p27 Cdk inhibitor proteins and the timing of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Dev Biol. 2002;245:224–234. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thullberg M, Bartek J, Lukas J. Ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation of p19INK4d determines its periodic expression during the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2000;19:2870–2876. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phelps DE, Hsiao KM, Li Y, Hu N, Franklin DS, Westphal E, Lee EY, Xiong Y. Coupled transcriptional and translational control of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p18INK4c expression during myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2334–2343. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polyak K, Kato J-Y, Solomon MJ, Sherr CJ, Massague J, Roberts JM, Koff A. p27Kip1, a cyclin-Cdk inhibitor, links transforming growth factor-beta and contact inhibition to cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev. 1994;8:9–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toyoshima H, Hunter T. p27, a novel inhibitor of G1 cyclin-Cdk protein kinase activity, is related to p21. Cell. 1994;78:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsushime H, Roussel MF, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Colony-stimulating factor 1 regulates novel cyclins during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cell. 1991;65:701–713. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsushime H, Quelle DE, Shurtleff SA, Shibuya M, Sherr CJ, Kato J-Y. D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2066–2076. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uziel T, Zindy F, Xie S, Lee Y, Forget A, Magdaleno S, Rehg JE, Calabrese C, Solecki D, Eberhart CG, Sherr SE, Plimmer S, Clifford SC, Hatten ME, McKinnon PJ, Gilbertson RJ, Curran T, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. The tumor suppressors Ink4c and p53 collaborate independently with Patched to suppress medulloblastoma formation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2656–2667. doi: 10.1101/gad.1368605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pickart CM, Fushman D. Polyubiquitin chains: polymeric protein signals. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ciechanover A, Ben-Saadon R. N-terminal ubiquitination: more protein substrates join in. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang KS, Guralnick BJ, Wang WK, Fersht AR, Itzhaki LS. Stability and folding of the tumour suppressor protein p16. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1869–1886. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venkataramani RN, MacLachlan TK, Chai X, El-Deiry WS, Marmorstein R. Structure-based design of p18INK4c proteins with increased thermodynamic stability and cell cycle inhibitory activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48827–48833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barton LF, Runnels HA, Schell TD, Cho Y, Gibbons R, Tevethia SS, Deepe GS, Jr, Monaco JJ. Immune defects in 28-kDa proteasome activator γ-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2004;172:3948–3954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wölfel T, Hauer M, Schneider J, Serrano M, Wölfel C, Klehmann-Hieb E, De Plaen E, Hankeln T, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Beach D. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science. 1995;269:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.7652577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruas M, Gregory F, Jones R, Poolman R, Starborg M, Rowe J, Brookes S, Peters G. CDK4 and CDK6 delay senescence by kinase-dependent and p16INK4a-independent mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4273–4282. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02286-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murray AW. Recycling the cell cycle: cyclins revisited. Cell. 2004;116:221–234. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ceruti JM, Scassa ME, Fló JM, Varone CL, Cánepa ET. Induction of p19INK4d in response to ultraviolet light improves DNA repair and confers resistance to apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:4065–4080. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scassa ME, Marazita MC, Ceruti JM, Carcagno AL, Sirkin PF, González-Cid M, Pignataro OP, Cánepa ET. Cell cycle inhibitor, p19INK4d, promotes cell survival and decreases chromosomal aberrations after genotoxic insult due to enhanced DNA repair. DNA Repair. 2007;6:626–638. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rechsteiner M, Hill CP. Mobilizing the proteolytic machine: cell biological roles of proteasome activators and inhibitors. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ragione FD, Russo GL, Oliva A, Mercurio C, Mastropietro S, Pietra VD, Zappia V. Biochemical characterization of p16INK4- and p18-containing complexes in human cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15942–15949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.15942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hawley RG, Lieu FH, Fong AZ, Hawley TS. Versatile retroviral vectors for potential use in gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1994;1:136–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Treier M, Staszewski LM, Bohmann D. Ubiquitin-dependent c-Jun degradation in vivo is mediated by the δ domain. Cell. 1994;78:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]