Abstract

Cutaneous tissue injury, both in vivo and in vitro, initiates activation of a “wound repair” transcriptional program. One such highly induced gene encodes plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 (PAI-1, SERPINE1). PAI-1-GFP, expressed as a fusion protein under inducible control of +800 bp of the wound-activated PAI-1 promoter, prominantly “marked” keratinocyte migration trails during the real-time of monolayer scrape-injury repair. Addition of active recombinant PAI-1 to wounded wild-type keratinocyte monolayers as well as to PAI-1−/− MEFs and PAI-1−/− keratinocytes significantly stimulated directional motility above basal levels in all cell types. PAI-1 expression knockdown or antibody-mediated functional inhibition, in contrast, effectively attenuated injury repair. The defect in wound-associated migratory activity as a consequence of antisense-mediated PAI-1 down-regulation was effectively reversed by addition of recombinant PAI-1 immediately after scrape injury. One possible mechanism underlying the PAI-1-dependent motile response may involve fine control of the keratinocyte substrate detachment/re-attachment process. Exogenous PAI-1 significantly enhanced keratinocyte spread cell “footprint” area while PAI-1 neutralizing antibodies, but not control non-immune IgG, effectively inhibited spreading with apoptotic hallmarks evident within 24 h. Importantly, PAI-1 not only stimulated keratinocyte adhesion and wound-initiated planar migration but also rescued keratinocytes from plasminogen-induced substrate detachment/anoikis. The early transcriptional response of the PAI-1 gene to monolayer trauma and its prominence in the injury repair genetic signature are consistent with its function as both a survival factor and regulator of the time course of epithelial migration as part of the cutaneous injury response program.

Keywords: PAI-1, SERPINE1, Wound healing, Keratinocytes, Gene targeting, Migration

Introduction

Activation of a global “wound repair’ genetic program appears to be a general response to serum as well as injury-simulating culture conditions [12, 17, 21, 25, 27, 30, 31, 39]. One particular transcript induced in abundance in wound-stimulated keratinocytes encodes plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 (PAI-1), a member of the serine protease inhibitor (SERPIN) gene family and the major physiologic regulator of the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA)-dependent pericellular plasmin-generating cascade [29, 39]. PAI-1 mRNA/protein increase rapidly in cultured epithelial cells immediately adjacent to experimentally-created wounds and remain elevated over the course of monolayer “healing” [12, 25, 29], closely recapitulating PAI-1 spatial/temporal induction in the wounded epidermis [18, 34]. Several SERPINS (i.e., PAI-1, protease nexin-1), in fact, modulate the complex integrative process of injury resolution largely through the focalized regulation of plasmin-initiated matrix remodeling, cell-to-substrate adhesion/detachment, migration and apoptosis [3, 7–10, 24, 26, 35, 40]. The effects of PAI-1 on cell migration, however, are not limited to its proteolytic inhibitory activity. While LDL receptor-related protein (LRP)-mediated endocytosis of uPA receptor (uPAR)-associated uPA/PAI-1 complexes has adhesive and motile consequences, promotion of migration by PAI-1 is not exclusively dependent on associations with uPA, tissue-type PA or vitronectin but does require binding to LRP [9]. LRP–PAI-1 interaction activates the Jak/Stat signaling pathway promoting Jak1 translocation to the leading edge and concomitant stimulation of cell motility [9].

Since PAI-1 is a highly up-regulated member of the “tissue repair” transcriptome and wound-initiated induction is restricted to the “activated” epidermal keratinocyte [12, 17, 27, 31], a quantifiable in vitro wound injury model [27] was adapted to assess the role of this SERPIN in the post-injury phase of trauma resolution. GFP-tagged PAI-1, expressed as a chimeric protein in engineered keratinocytes, prominantly “marked” cellular migration trails during the real-time of monolayer scrape-injury repair. Exogenous PAI-1, in fact, significantly increased wound-initiated motility in wild-type as well as PAI-1−/− keratinocytes. Most importantly, targeted PAI-1 knockdown and protein add-back approaches confirmed that PAI-1 not only stimulated wound-initiated planar migration but also rescued keratinocytes from plasminogen-induced substrate detachment/anoikis. The early transcriptional response of the PAI-1 gene to monolayer wounding and its prominence in the injury repair genetic signature are consistent with its role as both a survival factor and regulator of the temporal cadence of epithelial migration as part of the cutaneous injury response program.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HaCaT-II4 (human) and RK (rat) keratinocytes, PAI-1−/− and wild-type (PAI-1+/+) keratinocytes and PAI-1−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) were cultured as described [1, 19, 27]. Recombinant active PAI-1 (t1/2 = 145 h at 37°C; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) was used at final concentrations indicated in the text. PAI-1 neutralizing antibodies (AB778; Chemicon International), or control non-immune IgG, were added 10 min prior to and 6 h after monolayer wounding.

PAI-1-GFP chimera and anti-sense expression constructs

The human PAI-1 promoter (nucleotides −800 to +71) was PCR-amplified for 30 cycles using the p800-Luc reporter plasmid as a template. This fragment was gel-purified and cloned into the SacI/KpnI site of the promoter-less GFP expression vector pEGFP-1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). For preparation of a PAI-1-GFP chimeric expression construct, the full-length human PAI-1 coding sequence was derived by RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from human foreskin fibroblasts, amplified and expressed as a GFP fusion protein by insertion into the BamHI/AgeI site of the PAI-1 promoter pEGFP-1 vector. RK cells were seeded into 35 mm dishes and allowed to reach a density of 105 cells/cm2 prior to transfection with 1–2 μg DNA using Lipofect-amine-Plus. Transfected keratinocytes were trypsinized and plated at low cell density in EGF-supplemented (1 ng/ml) medium or grown to confluency, the monolayers serum-starved and scrape-wounded. In some cases, transfectants were removed from the culture dish by incubation in 0.2% saponin in Ca2+/Mg2+-free PBS leaving a substrate-attached saponin-resistant matrix. A BamHI/HindIII PAI-1 cDNA fragment, flanked with NotI linkers, was cloned into the Rc/CMV expression plasmid in antisense orientation (determined by restriction fragment mapping) to generate PAI-1 antisense transcripts [15]. Western blotting confirmed that Rc/CMVIAP transfection effectively down-regulated keratinocyte PAI-1 expression levels by at least 80%.

Cellular migratory and substrate detachment/viability assessments

Planar motile evaluations utilized the monolayer scrape wound assay [28]. The narrow end of a P1000 pipette tip was pushed through quiescent monolayers to create scratch wounds approximately 0.1 cm wide. Lines were drawn on the bottom of the culture dish at intervals along the scrape track to identify specific sites for successive injury “repair” measurements. The reference lines were aligned with the bottom of an ocular grid to determine the width of the denuded zone initially, at the time of wounding, and at subsequent pre-determined times; this method insured that the same areas of the wound track were consistently monitored. For substrate adhesion/survival evaluations, HaCaT-II4 cells were grown to approximately 40% confluency (as confirmed by ocular grid microscopy) and the medium replaced with serum-free DMEM containing 1% BSA. Plasminogen (20 μg/ml; 0.22 μM) and/or PAI-1 were added 24 h later for an additional 6 or 48 h. The number of attached cells per unit area was determined at 6 h by microscopy of crystal violet-stained cultures using a calibrated ocular grid. The fraction of the total recovered population (adherent + detached keratinocytes) capable of producing viable colonies upon transfer of 500 cells to 150 cm2 culture dishes DMEM/10% FBS (after a 48-h exposure to serum-free medium containing plasminogen ±PAI-1) was used to calculate a survival index.

Results

PAI-1 positively affects experimental wound repair

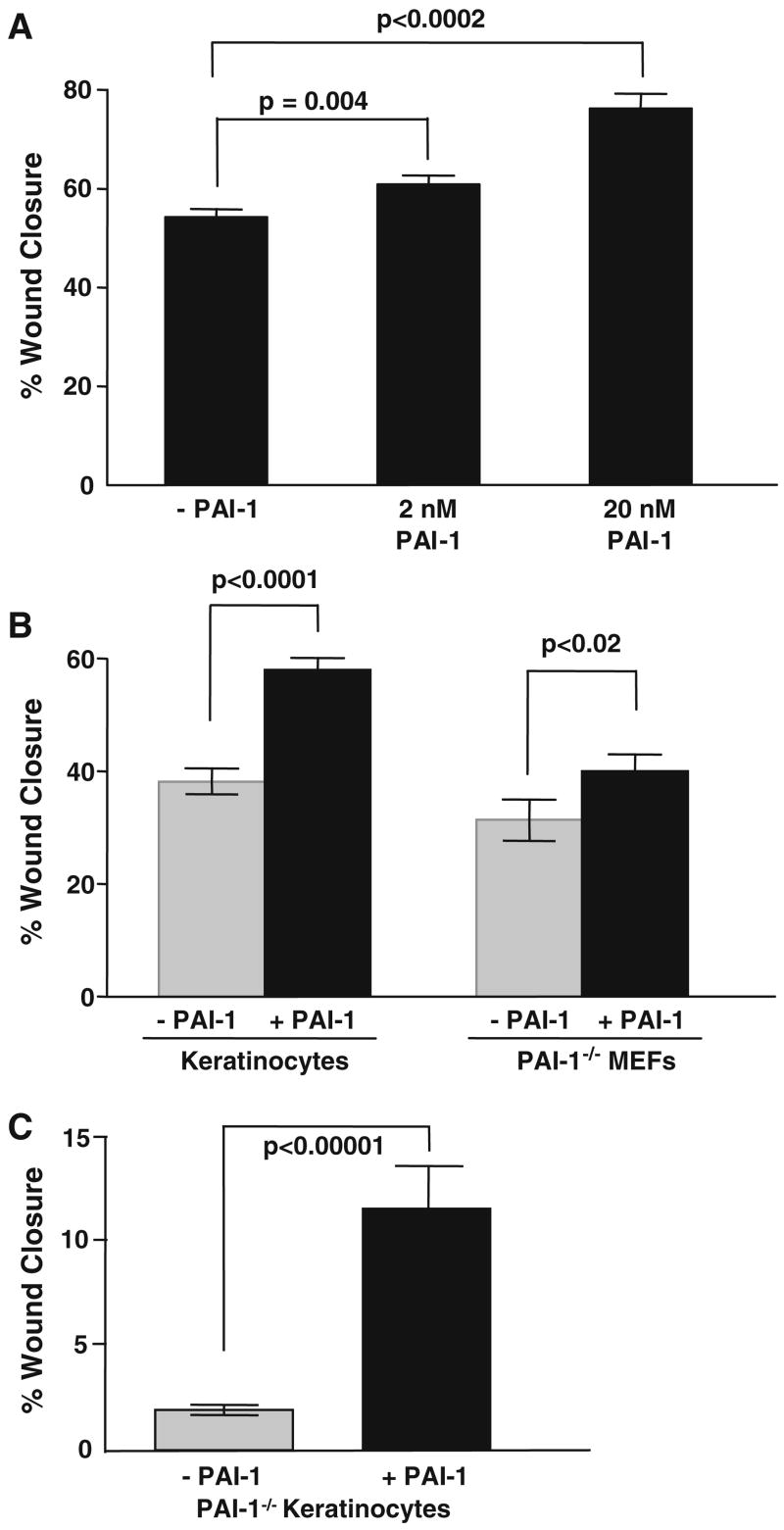

Expression of a PAI-1-GFP fusion construct, under inducible regulation by +800 bp of the wound-activated PAI-1 promoter, provided for the direct visualization of PAI-1-GFP deposition in keratinocyte migration tracks (Fig. 1a–c). GFP when expressed alone (i.e., without linkage to PAI-1) accumulated, by virtue of its localization sequence, in the nucleus and not in migration trails (Fig. 1d). Removal of cells with saponin prior to microscopy indicated that keratinocytes specifically deposited the PAI-1-GFP chimera into the ventral undersurface “matrix” (Fig. 1e, f). Indeed, the rapid deposition of PAI-1 in the matrix-associated keratinocyte migration trails as a consequence of monolayer wounding or stimulation with EGF was similar in time frame and directionality as that reported by Seebacher et al. [36]. Such spatial restrictions on PAI-1 deposition in the context of experimental scrape repair are consistent with involvement in the motile response [9, 27]. Addition of active recombinant PAI-1 to wounded HaCaT-II4 (Fig. 2a) or RK (Fig. 2b) keratinocyte monolayers as well as to PAI-1−/− MEFs and PAI-1−/− keratinocytes (Fig. 2b, c), in fact, significantly stimulated directional motility above basal levels in all cell types. PAI-1 expression antisense knockdown or functional inhibition (with neutralizing antibodies), in contrast, effectively attenuated injury repair (Fig. 3a, b). To more conclusively implicate PAI-1 as a regulator of epidermal migration, a combined molecular knockdown/wound repair “rescue” strategy was devised. The defect in wound-associated migratory activity characteristic of wild-type keratinocytes as a consequence of constitutive expression of a PAI-1 antisense construct resulting in PAI-1 down-regulation (Fig. 3a) was effectively reversed by addition of recombinant PAI-1 (Fig. 3b). Such restoration of the motile response to monolayer wounding was evident as early as 2 h post-injury (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 1.

PAI-1 is deposited into keratinocyte migration tracks. RK cells were transfected with the PAI-1 promoter-driven PAI-1-GFP insert construct, grown to confluency, serum-deprived and the monolayers subjected to a single (horizontal) or dual (perpendicular) scrape injury (a, b). In either instance, the direction of cell migration and the elaboration of GFP-tagged PAI-1-rich migration “trails” was toward the denuded zones. Keratinocytes transfected with the PAI-1 promoter-driven PAI-1-GFP chimera (c) or the PAI-1 promoter-driven GFP only (d) expression vectors were cultured at low cell density, serum-starved, then stimulated with EGF. Although both populations were highly motile, only the PAI-1-GFP chimera-expressing cells developed GFP-labeled migration tracks (c). No labeled trails were evident in keratinocytes that expressed only GFP (i.e., in the absence of the PAI-1 coding sequence insert) (d) confirming that the tracks (in a–c) were sites of deposition of the PAI-1-GFP fusion protein. Removal of RK cells with saponin confirmed that PAI-1-GFP did, in fact, accumulate in the ventral undersurface, substrate-attached, matrix (e). Phase-contrast microscopy (f) of the identical field (in e) assured that the saponin procedure released keratinocyte bodies while retaining an attached matrix residue

Fig. 2.

PAI-1 stimulates wound-initiated migration of wild-type and PAI-1−/− cells. Confluent monolayers of HaCaT-II4 and RK keratinocytes as well as PAI-1−/− MEFs were serum-deprived prior to scratch injury. Addition of PAI-1 protein to the medium immediately after scraping significantly stimulated wound closure (as assessed 24 h post-injury) in HaCaT-II4 keratinocytes (P = 0.004 and P < 0.0001 for 2 and 20 nM PAI-1, respectively) (a), RK cells (P < 0.0001) and PAI-1−/− MEFs (P < 0.02) (both at 20 nM PAI-1) (b). Data (in a, b) is the mean ±SD of at least five separate measurements on each of three independent cultures. Primary keratinocytes from PAI-1−/− and PAI- 1+/+ mice were grown to confluency and maintained under quiescence prior to monolayer wounding. PAI-1−/− keratinocytes have a significant migratory defect relative to wild-type cells (P < 0.0001). Addition of active PAI-1 protein (20 nM) to the medium restored PAI-1−/− keratinocyte migration (P < 0.0001) by 6 h to that approximating wild-type cells (c). Data plotted (in c) is the mean ± SD of 15 individual measurements on duplicate cell cultures

Fig. 3.

PAI-1 expression knockdown with the Rc/CMVIAP antisense construct attenuates planar migration in wounded keratinocyte monolayers. Transfection of RK cells with the Rc/CMVIAP antisense vector reduced wound-induced PAI-1 expression by approximately 80–85% (western blot insert in a; V vector control, AS antisense construct) and significantly impaired scrape site repair (a). Addition of PAI-1 neutralizing antibodies similarly and dose-dependently decreased keratinocyte migration compared to control (non-immune) IgG PAI-1 neutralizing antibodies were added 10 min prior to scrape injury (1×) or again at 6 h post-wounding (2×). Vector and IgG control cultures were allowed to reach approximately complete injury site closure prior to assessment of effects of PAI-1 antisense constructs or neutralizing IgG on the motile response. Histogram (in a) illustrates the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. To evaluate the potential of exogenously-delivered PAI-1 to rescue the motile phenotype in PAI-1 knockdown keratinocytes, RK cells transfected with the Rc/CMVIAP construct were divided into two sets of cultures and grown to confluency. Addition of active recombinant PAI-1 (20 nM) immediately after wounding restored the migratory phenotype with a significant positive effect on keratinocyte motility evident as early as 2 h post-injury and throughout the 20-h assessment period (b). Data plotted (in b) is the mean ± SD for three independent experiments

PAI-1 regulates keratinocyte adhesion/substrate detachment and promotes adhesion-dependent survival

One possible mechanism underlying the PAI-1-dependent motile response likely involves fine control of the keratinocyte substrate detachment/re-attachment process. Immobilized PAI-1, in fact, promoted cell adhesion and spreading in a dose-dependent manner in human myogenic cells functioning as part of a multimolecular complex that included integrins, uPA and uPAR [26]. Exposure to recombinant PAI-1 (20 nM in serum-free medium) rapidly increased (by 42%) the keratinocyte footprint area (Fig. 4a). Seeding of keratinocytes to growth medium containing PAI-1 neutralizing antibodies but not control non-immune IgG, moreover, effectively inhibited cell spreading (Fig. 4b) with hallmarks of apoptosis (e.g., refractile cell bodies, cytoplasmic blebbing, nuclear condensation) evident by 24 h. These data and previous findings [5, 9, 26] collectively suggest that PAI-1 may regulate cycles of cell-to-substrate adhesion/detachment to effect efficient migration while promoting attachment-dependent keratinocyte survival. Indeed, PAI-1−/− cells are significantly more sensitive to apoptotic stimuli compared to their PAI-1+/+ counterparts [33] and loss of substrate anchorage initiates a rapid apoptotic response by HaCaT-II4 cells [4]. To assess potential pro-survival activities of PAI-1 in human keratinocytes, the effects of a physiologic regulator of epidermal cell detachment (plasminogen) [13, 32] were assessed in the presence or absence of recombinant PAI-1. The medium in approximately 40% confluent HaCaT-II4 cultures was replaced with serum-free DMEM containing 1% BSA; 24 h later, plasminogen (0.22 μM, final concentration) ±PAI-1 were added. The rapid cell body retraction and substrate release of HaCaT-II4 keratinocytes upon plasminogen exposure was significantly attenuated by exogenous PAI-1 (Fig. 4c). The PAI-1-dependent rescue of the adhesive phenotype was reflected in a significant increase in the HaCaT-II4 survival index compared to keratinocytes exposed to plasminogen alone (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

PAI-1 modulates keratinocyte substrate spreading and plasminogen-mediated substrate detachment. RK cells were cultured at low density, the growth medium aspirated and replaced with serum-free medium with or without added PAI-1 (20 nM) or PAI-1 neutralizing antibodies; 6 h (for PAI-1) or 24 h (for PAI-1 Ab) later, the cells were fixed, permeabilized and the actin cyctoskeleton visualized for computerized determination of cell spread area using Texas Red Phalloidin. PAI-1 supplementation induced a significant increase in cell-spread area (P > 0.0001) (a) while PAI-1 neutralizing antibodies almost completely blocked spreading (b). Data plotted (in a, b) is the mean ± SD of cell area measurements for 100 randomly selected control and PAI-1-treated keratinocytes. One possibility for the increase in cell spreading in PAI-1-supplemented cultures is that PAI-1 modulates pericellular proteolysis and, thereby, keratinocyte adhesion. Plasminogen (Plg 0.22 μM, final concentration) was added to 40% confluent serum-free HaCaT-II4 cell cultures with or without simultaneous addition of recombinant PAI-1 (20 nM). Cells were fixed in formalin 6 h later, permeabilized with methanol, stained with crystal violet and the number of attached cells per unit area determined by ocular grid microscopy. Plasminogen-induced rapid keratinocyte retraction and subsequent detachment; substrate release was significantly attenuated by PAI-1 (c). The fraction of the total recovered HaCaT-II4 population capable of producing viable colonies upon transfer to DMEM/10% FBS (after a 48-h exposure to serum-free medium containing plasminogen ±PAI-1) was used as a measure of keratinocyte viability. The survival index for plasminogen + PAI-1 cultures was >4-fold than that of non-PAI-1-treated keratinocytes indicating that exogenous PAI-1 effectively protected HaCaT-II4 cells from plasminogen-induced loss of viability. Data (in c, d) represents the mean ±SD of triplicate experiments. Crystal violet staining of low-density quiescent (Q) and 7-day serum-stimulated (Q → S) HaCaT-II4 cultures (insert in d) indicated that the conditions of quiescence arrest was accompanied by complete growth recovery confirming the usefulness of the model system for viability assessments

Discussion

Cutaneous injury initiates a complex signaling response that results in the reprogramming of gene expression necessary to integrate the various temporal and spatial facets of tissue repair (i.e., cell migration, growth, matrix remodeling) [22]. Refinements in the development of in vitro or ex vivo systems that recapitulate particular aspects of post-trauma re-epithelialization have made it possible to define specific mechanisms underlying injury-initiated keratinocyte “activation” [11, 12, 23, 25, 27, 39, 41]. Indeed, the regional-restriction of uPA/PAI-1PAI-1 expression as well as the spatial/temporal distinctions among the differentiated, motile and proliferative compartments typical of injury repair in vivo can be recreated during cell migration into the denuded areas of a scrape-injured monolayer [reviewed in 27]. Several hallmarks of epidermal injury resolution (i.e., MAP kinase activation, PAI-1 induction, matrix remodeling, proliferative compartmentalization) are reproduced, moreover, in scrape-wounded keratinocyte monolayers [12, 27, 39] validating use of this culture model to frame molecular events associated with the repair process.

The present paper highlights two important findings with regard to keratinocyte biology that have not been considered previously. The defect in wound-associated keratinocyte migration as a consequence of antisense-mediated PAI-1 knockdown was effectively reversed by addition of recombinant PAI-1 immediately after scrape injury. One possible mechanism underlying the PAI-1-dependent motile response may involve fine control of the keratinocyte substrate detachment/re-attachment process. Perhaps as importantly, PAI-1 not only stimulated keratinocyte adhesion and wound-initiated planar migration but also rescued keratinocytes from plasminogen-induced substrate detachment/anoikis. These effects may reflect the fact that PAI-1 accumulates specifically in the cellular undersurface region where it is well-positioned to modulate integrin–ECM or uPA/uPAR–ECM interactions as well as stromal remodeling [2, 3, 6, 8–10, 14, 15, 20, 24, 29, 37, 42]. Activation of the PAI-1 gene early after monolayer wounding and its prominence in the injury repair transcriptome are consistent with the present data suggesting a dual function for PAI-1 (i.e., as a keratinocyte survival factor and regulator of epithelial migration) in the cutaneous injury response program. In the latter context, changes in PAI-1 expression could impact motile behavior by modulating uPA-dependent pericellular proteolysis and/or cell-to-matrix adhesion [42]. PAI-1 limits uPA-mediated pericellular plasmin generation and stromal degradation likely maintaining a “scaffold” permissive for cell migration [3, 42]. PAI-1 also disrupts vitronectin–uPAR interactions, detaching cells that utilize this receptor as a matrix anchor and inhibiting αv integrin-mediated attachment to vitronectin by blocking accessibility to the RGD motif [10]. uPAR-associated uPA/PAI-1 complexes, moreover, are endocytosed by LRP family members potentially altering LRP and/or uPAR signaling events important in migratory decisions [6, 7, 9]. Collectively, PAI-1 may function within the global program of the tissue repair response to coordinate cycles of cell-to-substrate adhesion/detachment [7, 8, 10, 24, 27, 29]. The association between the activated phenotype and targeted accumulation of PAI-1 in close proximity to newly formed focal adhesions [20] is consistent with this function. PAI-1 may also influence substrate attachment directly, as one component in the molecular complex that bridges the cell and the ECM [26], additionally suggesting PAI-1 can affect adhesion when presented to cells as both a soluble as well matrix-anchored SERPIN [9, 21, 24, 26]. Targeting PAI-1 gene expression and/or PAI-1 function may provide a novel, therapeutically-relevant approach, to manage the pathophysiology of PAI-1-associated cutaneous fibrosis and other wound healing disorders [16, 38].

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant GM57242.

References

- 1.Allen RR, Qi L, Higgins PJ. Upstream stimulatory factor regulates E box-dependent PAI-1 transcription in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203:156–165. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen PA, Egelund R, Peterson HH. The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:25–40. doi: 10.1007/s000180050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajou K, Masson V, Gerard RD, Schmitt PM, Albert V, Praus M, Lund LR, Frandsen TL, Brunner N, Dano K, Fusenig NE, Weidle U, Carmeliet G, Loskutoff D, Collen D, Carmeliet P, Foidart JM, Noel A. The plasminogen activator inhibitor PAI-1 controls in vivo tumor vascularization by interaction with proteases, not vitronectin. Implications for antiangiogenic strategies. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:777–784. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bretland AJ, Lawry J, Sharrard RM. A study of death by anoikis in cultured epithelial cells. Cell Prolif. 2001;34:199–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2001.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks TD, Slomp J, Quax PHA, De Bart ACW, Spencer MT, Verheijen JH, Charlton PA. Antibodies to PAI-1 alter the invasive and migratory properties of human tumour cells in vitro. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2001;18:445–453. doi: 10.1023/a:1011882421528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman HA, Wei Y. Protease crosstalk with integrins: the urokinase receptor paradigm. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chazaud B, Ricoux R, Christov C, Plonquet A, Gherardi RK, Barlovatz-Meimon G. Promigratory effect of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 on invasive breast cancer populations. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:237–246. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czekay R-P, Aertgeerts K, Curriden SA, Loskutoff DJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 detaches cells from extracellular matrices by inactivating Integrins. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:781–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degryse B, Neels JG, Czekay R-P, Aertgeerts K, Kamikubo T, Loskutoff DJ. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein is a motogenic receptor for plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22595–22604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng G, Curriden SA, Hu G, Czekay R-P, Loskutoff DJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates cell adhesion by binding to the somatomedin B domain of vitronectin. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:23–33. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieckgraefe BK, Weems DM, Santoro SA, Alpers DH. p38 MAP kinase pathways are mediators of intestinal epithelial wound-induced signal transduction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:23–33. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitsialos G, Chassot AA, Turchi L, Dayem MA, LeBrigand K, Moreilhon C, Meneguzzi G, Busca R, Mari B, Barbry P, Ponzio G. Transcriptional signature of epidermal keratinocytes subjected to in vitro scratch wounding reveals selective roles for ERK1/2, p38, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15090–15102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geer DJ, Andreadis ST. A novel role of fibrin in epidermal healing: plasminogen-mediated migration and selective detachment of differentiated keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1210–1216. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez LS, Schulman A, Brito-Robinson T, Noria F, Ploplis VA, Castellino FJ. Tumor development is retarded in mice lacking the gene for urokinase-type plasminogen activator or its inhibitor, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5839–5847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins PJ, Ryan MP, Jelley DM. p52PAI-1 gene expression in butyrate-induced flat revertants of v-ras-transformed rat kidney cells: mechanism of induction and involvement in the morphologic response. Biochem J. 1997;321:431–437. doi: 10.1042/bj3210431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins PJ, Slack JK, Diegelmann RF, Staiano-Coico L. Differential regulation of PAI-1 gene expression in human fibroblasts predisposed to a fibrotic phenotype. Exp Cell Res. 1999;248:634–642. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyer VR, Eisen MB, Ross DT, Schuler G, Moore T, Lee JC, Trent JM, Staudt LM, Hudson J, Boguski MS, Lashkari D, Shalon D, Botstein D, Brown PO. The transcriptional program in the response of human fibroblasts to serum. Science. 1999;283:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen PJ, Lavker RM. Modulation of the plasminogen activator cascade during enhanced epidermal proliferation in vivo. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1793–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kortlever RM, Higgins PJ, Bernards R. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a critical downstream target of p53 in the induction of replicative senescence. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:877–884. doi: 10.1038/ncb1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutz SM, Nickey S, White LA, Higgins PJ. Induced PAI-1 mRNA expression and targeted protein accumulation are early G1 events in serum-stimulated rat kidney cells. J Cell Physiol. 1997;170:8–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199701)170:1<8::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maquerlot F, Galiacy S, Malo M, Guignabert C, Lawrence DA, d’Ortho MP, Barlovatz-Meimon G. Dual role for plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 as a soluble and as matricellular regulator of epithelial alveolar cell healing. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1624–1632. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin P. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;176:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzalupo S, Wawersik MJ, Coulombe PA. An ex vivo assay to assess the potential of skin keratinocytes for wound epithelialization. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:866–870. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmeri D, Lee JW, Juliano RL, Church FC. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and -3 increase cell adhesion and motility in MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40950–40957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawar S, Kartha S, Tobeck FG. Differential gene expression in migrating renal epithelial cells after wounding. J Cell Physiol. 1995;165:556–565. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Planus E, Barlovatz-Meimon G, Rogers RA, Bonavaud S, Ingber DF, Wang N. Binding of urokinase to plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 mediates cell adhesion and spreading. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1091–1098. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.9.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Providence KM, Higgins PJ. PAI-1 expression is required for epithelial cell migration in two distinct phases of in vitro wound repair. J Cell Physiol. 2004;200:297–308. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Providence KM, Staiano-Coico L, Higgins PJ. A quantifiable in vitro model to assess effects of PAI-1 gene targeting on epithelial cell motility. Methods Mol Med. 2003;78:293–303. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-332-1:293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Providence KM, White LA, Tang J, Gonclaves J, Staiano-Coico L, Higgins PJ. Epithelial monolayer wounding stimulates binding of USF-1 to an E-box motif in the plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 gene. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3767–3777. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi L, Allen RR, Lu Q, Higgins CE, Garone R, Staiano-Coico L, Higgins PJ. PAI-1 transcriptional regulation during the transition in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Cell Bio-G0→ G1 chem. 2006;99:495–507. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi L, Higgins SP, Lu Q, Samarakoon R, Wilkins-Port CE, Ye Q, Higgins CE, Staiano-Coico L, Higgins PJ. SERPINE1 (PAI-1) is a prominent member of the early G0→ G1 transition “wound repair” transcriptome in p53 mutant human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;128:749–753. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinartz J, Link J, Todd RF, Kramer MD. The receptor for urokinase-type plasminogen activator of a human keratinocyte line (HaCaT) Exp Cell Res. 1994;214:486–498. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romer MU, Kirkebjerg Due A, Knud Larsen J, Hofland KF, Christensen IJ, Buhl-Jensen P, Almholt K, Lerberg Nielsen O, Brunner N, Lademann U. Indication of a role of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in protecting murine fibrosarcoma cells against apoptosis. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:859–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romer J, Lund LR, Kriksen J, Ralkiaer E, Zeheb R, Gelehrter TD, Dano K, Kristensen P. Differential expressin of urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its type-1 inhibitor during healing of mouse skin wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;102:519–522. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12486833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossignol P, Ho-Tin-Noe B, Vranckx R, Bouton MC, Meilhac O, Lijnen HR, Guillin MC, Michel JB, Angles-Cano E. Protease nexin-1 inhibits plasminogen activation-induced apoptosis of adherent cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10346–10356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seebacher T, Manske M, Zoller J, Crabb J, Bade EG. The EGF-inducible protein EIP-1 of migrating normal and malignant rat liver epithelial cells is identical to plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 and is a component of the ECM migration tracks. Exp Cell Res. 1992;203:504–507. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefansson S, Lawrence DA. Old dogs and new tricks: proteases, inhibitors, and cell migration. Sci STKE. 2003;2003(189):24. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.189.pe24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuan TL, Zhu JY, Sun B, Nichter LS, Nimni ME, Laug WE. Elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 may account for the altered fibrinolysis by keloid fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:1007–1011. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12338552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turchi L, Chassot AA, Rezzonico R, Yeow K, Loubat A, Ferrua B, Lenegrate G, Ortonne JP, Ponzio G. Dynamic characterization of the molecular events during in vitro epidermal wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:56–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z, Sosne G, Kurpakus-Wheater M. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) stimulates human corneal epithelial cell adhesion and migration in vitro. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wawersik MJ, Mazzalupo S, Nguyen D, Coulombe PA. Increased levels of keratin 16 alter epithelialization potential of mouse skin keratinocytes in vivo and ex vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3439–3450. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkins-Port CE, Higgins PJ. Regulation of extracellular matrix remodeling following TGF-β1/EGF-stimulated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human pre-malignant keratinocytes. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:116–122. doi: 10.1159/000101312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]