Abstract

Because most critically ill patients lack decision-making capacity, physicians often ask family members to act as surrogates for the patient in discussions about the goals of care. Therefore, clinician-family communication is a central component of medical decision making in the ICU, and the quality of this communication has direct bearing on decisions made regarding care for critically ill patients. In addition, studies suggest that clinician-family communication can also have profound effects on the experiences and long-term mental health of family members. The purpose of this narrative review is to provide a context and rationale for improving the quality of communication with family members and to provide practical, evidence-based guidance on how to conduct this communication in the ICU setting. We emphasize the importance of discussing prognosis effectively, the key role of the integrated interdisciplinary team in this communication, and the importance of assessing spiritual needs and addressing barriers that can be raised by cross-cultural communication. We also discuss the potential value of protocols to encourage communication and the potential role of quality improvement for enhancing communication with family members. Last, we review issues regarding physician reimbursement for communication with family members within the context of the US health-care system. Communication with family members in the ICU setting is complex, and high-quality communication requires training and collaboration of a well-functioning interdisciplinary team. This communication also requires a balance between adhering to processes of care that are associated with improved outcomes and individualizing communication to the unique needs of the family.

Keywords: communication, critical care, end-of-life care, family, medical decision making, palliative care

Because most critically ill patients do not have decision-making capacity, family members frequently become involved with clinicians in discussions about the goals of care and often must represent patients' values and treatment preferences in these discussions.1 Therefore, clinician-family communication is a central component of good medical decision making in the ICU. Prior studies2 suggest that family members view clinicians' communication skills as more important than our clinical skills. However, clinician-family communication in the ICU is often inadequate. One study3 found that only half of families of ICU patients sufficiently understand basic information about patients' diagnoses, prognoses, or treatments after a discussion with clinicians. Another study4 found that clinician-family communication commonly does not meet the basic standards of informed decision making. The purpose of this narrative review is to provide a context and rationale for improving the quality of communication with family members within the ICU and to provide practical, evidence-based guidance on how to conduct this communication. We propose that this approach be used for major decisions that depend heavily on patients' values and preferences, such as decisions about limiting life-sustaining treatments when survival is unlikely but possible and when survival may come with significant future functional impairment. We do not advocate this approach for routine medical decisions or for cases of strict medical futility.

Rationale for Focusing on Communication With Family Members

Family members are becoming an increasing part of caregiving for seriously ill patients, whether this is informal support and care in the home or surrogate decision making in the ICU.5,6 Informal care and decision making provided by family, partners, and friends constitute a growing portion of the health care provided to seriously ill patients.7-10 Furthermore, approximately 20% of deaths in the United States occur in the ICU, and most of these deaths involve family members acting as surrogates for the patient.11,12 However, being a family caregiver is a difficult job, associated with significant emotional burdens,13 and is frequently performed by people who are themselves elderly, ill, or disabled.14,15 Studies16-19 demonstrate that almost half of all family caregivers and surrogate decision makers experience significant symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Caregiving is also associated with increased caregiver mortality.20-22 Despite the emotional and health burdens of being a family caregiver, our health-care system does not provide adequate support for family caregivers.23 Many physicians and health-care systems do not consider the family to be a focus of their care.23 The American Medical Association has called on the health-care system to acknowledge that family and clinicians are interdependent and to develop a care partnership in order to improve outcomes for patients and family members, but this is often an unrealized goal.24 Several critical care professional societies have highlighted the importance of focusing on the family.25-27

In the ICU setting, there is an additional reason to focus on the needs of the family. Since family members are often serving as surrogate decision makers, decisions about the care of the patient depend in part on the family. To the extent that family members' distress affects their ability to provide substituted judgment, these burdens of family members can interfere with patient care. Therefore, effective communication with family members that minimizes stress on the family and provides support for the family will improve not only family outcomes but also medical decision making for the critically ill patient.

The Role of Shared Decision Making

There is general consensus that physicians caring for critically ill patients have an obligation to disclose information about a patient's medical condition and prognosis to family members, and also that family members are an important source of information about the patient's values and treatment preferences. Furthermore, there is consensus that family members' fulfilling this role should be counseled to use the principle of substituted judgment to guide decisions when possible, attempting to answer the question of what the patient would say if he or she were able to participate.28 Although a number of distinct approaches to conceptualizing the physician-patient or physician-surrogate relationship have been proposed,29-32 in our experience critical care physicians often conceptualize their role in one of three distinct ways: (1) parentalism, in which the physician makes the treatment decision with little input from the patient or family; (2) informed choice, in which the physician provides all relevant medical information but withholds his or her opinion and places responsibility for the decision on the family; and (3) shared decision making, in which the physician and family each share their opinions and jointly reach a decision. In 2005, five European and North American critical care societies issued a joint consensus statement advocating shared decision making about life support in ICUs.6 This consensus statement characterizes a shared decision as one in which “responsibility for decisions is shared jointly by the treating physician and the patient's family.”6 Similarly, shared decision making was also endorsed by the American College of Critical Care clinical practice guidelines for support of the family during patient-centered critical care.25

Family members of critically ill patients vary in how involved they want to be in decisions about life support. The majority want the physician to provide a recommendation about whether to limit life support and then share in the final decision. However, it is important to realize that there is a spectrum of preferences, ranging from letting the physician decide to the family member assuming all responsibility for the final decision.33 Therefore, family-centered decision making requires that clinicians assess the families' preferred role in decision making rather than assume “one size fits all.” In addition, high-quality shared decision making is a process with a number of important components and not simply an agreement to allow family members to be involved in decision making. Table 1 describes the components of shared decision making based on prior theoretical models and empiric evaluation of communication during ICU family conferences.4,34

Table 1.

Components of Shared Decision Making Adapted to the ICU Family Conference*

| Dimensions of Shared Decision Making | Example of Physician Behaviors and Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| Providing medical information and eliciting patient values and preferences | Discuss nature of decision | |

| What are the essential clinical issues we are addressing? | ||

| Describe alternatives | ||

| What are the clinically reasonable choices? | ||

| Discuss pros/cons | ||

| What are the pros and cons of the treatment choices? | ||

| Discuss uncertainty | ||

| What is the likelihood of success of treatment and how confident are we in this estimate? | ||

| Assess understanding | ||

| Is the family now an “informed participant,” with a working understanding of the decision? | ||

| Explore patient's values/preferences | ||

| What is known about patient's medical preferences or values? What is important to the patient? | ||

| Exploring family's preferred role in decision making | Discuss family's role | |

| What role should the family play in making the decision? | ||

| Assess desire for other's input | ||

| Is there anyone else the family would like to consult? | ||

| Deliberation and decision making | Explore “context” | |

| How will the decision impact the patient's life? | ||

| If the family is to participate in decision-making, elicit family opinion about best treatment choice | ||

| What does the family think is the most appropriate decision for the patient? | ||

Adapted from White and colleagues.4

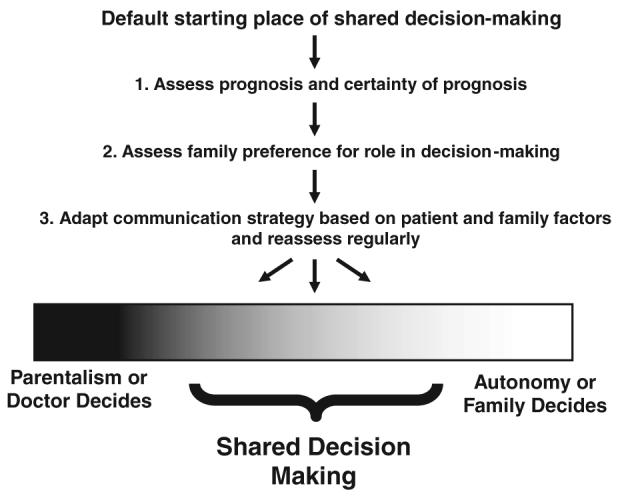

We advocate that clinicians should tailor their approach to communication to the individual families' decision-making preferences. Figure 1 outlines a potential approach to match the clinicians' role with the families' needs, for which the default starting position is one of shared decision making. This default position is modified by three subsequent steps. First, the clinicians should consider the prognosis and the certainty of the prognosis. As the prognosis becomes poorer and the certainty about this prognosis becomes higher, physicians should be more willing to offer to take on some of the burden of decision making. For some family members, the process may be best conceptualized as providing “informed assent.”35 This informed assent approach allows family members to cede responsibility for difficult decisions to clinicians and generally requires both a very poor prognosis and a high level of certainty about the prognosis. However, it is important that physicians allow family members the opportunity to be involved in decision making if they choose to do so. Therefore, steps two and three are to inquire into the families' preferred role, then adapt one's approach to these patient and family factors. Our experience has been that elicitation of role preferences is often ineffective when it occurs before the family understands the nature of the decisions at hand. We therefore advocate for a process of ongoing conversations during which clinicians look for cues from family members about their preferred role in decision making, and then use those cues as a starting point for explicit discussion about roles in decision making. In addition, the chosen approach should be reassessed over time because family preferences may change over time or with a changing prognosis. In this way, shared decision making is not viewed as “one size fits all” or as a static one-time decision, but rather as a process that is responsive to the needs of the family.

Figure 1.

Three-step approach to patient- and family-centered decision making that advocates for a default starting place of shared decision making that can be modified by prognosis and certainty of prognosis and also by family preferences for role in decision making.

Shared decision making also requires physicians to be expert in helping family members understand and articulate patients' values. Exploring patients' preferences and the appropriate influence of those preferences on medical decision making is one of the common missed opportunities during ICU family conferences.36 An important approach to accomplishing this component of shared decision making is asking open-ended questions that allow the family to describe what is important to the patient and explore how this informs decision making about treatments. It is also important to focus the family on what the patient would say if he or she were able to participate in the decision making.

Communication With Family Members of all Critically Ill Patients

With increasing focus on improving end-of-life care in the ICU, we run the risk of forgetting the family of patients who survive their ICU stay. There are several reasons to focus on communication with the families of all critically ill patients. First, it is generally not clear whether critically ill patients will survive at the time when clinician-family communication should be occurring. Second, although the patient's death in the ICU is a risk factor for psychological symptoms among family members, even family of patients who survive are at increased risk of these symptoms compared to the general population.19 Finally, there is evidence that family members of patients who survive are actually less satisfied with communication from ICU clinicians than family of patients who die.37 If we are to be truly effective in improving clinician-family communication, we must attempt to improve this communication for the family of all critically ill patients.

An Evidence-Based Approach to Communication During the ICU Family Conference

Discussions between ICU clinicians and family members about goals of care and medical decision making often take place during ICU family conferences. Conduct of these conferences within 72 h of ICU admission has been associated with reduced days in the ICU for patients that die and with higher ratings of the quality of dying among family members.38,39 There are also specific features of these conferences that have been associated with improved family experience or with better assessment of the quality of communication. Improved family outcomes have been associated with having a private place for family communication and with consistent communication by all members of the health-care team.16 A “preconference” may help meet the latter goal, in which the interdisciplinary team discusses the goals of the family conference and reaches consensus on the prognosis and on what treatments are indicated.40 During the conference, family members are more satisfied with clinician communication when clinicians spend more time listening and less time talking.41 Other features of clinician communication that are associated with improved family experiences include assurances that the patient will not be abandoned prior to death; assurances that the patient will be comfortable and will not suffer; and support for a family's decisions about care, including support for family's decision to withdraw or not to withdraw life support.42 In addition, empathic statements by clinicians have also been associated with increased family satisfaction.43 The three most common types of empathic statements in this setting are statements that explicitly acknowledge the difficulty of having a critically ill loved one, the difficulty of surrogate decision making, and the sadness of having a loved one die. Finally, evaluation by investigators suggest categories of important missed opportunities during ICU family conferences, including the opportunity to listen and respond to family members' questions, the opportunity to acknowledge and address family emotions, and the opportunity to address basic tenets of palliative care including the exploration of patient preferences, explanation of the principles of surrogate decision making, and assuring nonabandonment by clinicians.36,44 Table 2 summarizes the components of clinician-family communication that have been associated with increased quality of care, decreased family psychological symptoms, or improved family ratings of communication.

Table 2.

Additional Communication Components Shown to be Associated With Increased Quality of Care, Decreased Family Psychological Symptoms, or Improved Family Ratings of Communication

| Conduct family conference within 72 h of ICU admission38,39 | |

| Identify a private place for communication with family members16 | |

| Provide consistent communication from different team members16 | |

| Increase proportion of time spent listening to family rather than talking41 | |

| Empathic statements43 | |

| Statements about the difficulty of having a critically ill loved one | |

| Statements about the difficulty of surrogate decision making | |

| Statements about the impending loss of a loved one | |

| Identify commonly missed opportunities36 | |

| Listen and respond to family members | |

| Acknowledge and address family emotions | |

| Explore and focus on patient values and treatment preferences | |

| Explain the principle of surrogate decision making to the family (the goal of surrogate decision making is to determine what the patient would want if the patient were able to participate) | |

| Affirm nonabandonment of patient and family44 | |

| Assure family that the patient will not suffer42 | |

| Provide explicit support for decisions made by the family42 | |

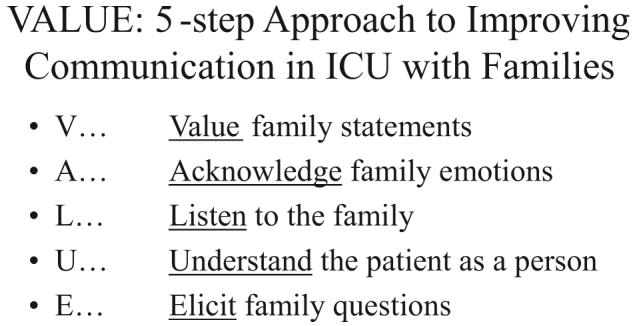

Several of these findings have been combined into a mnemonic for five features to enhance clinician-family communication: VALUE (value, acknowledge, listen, understand, and elicit) [Fig 2]. This mnemonic has been used as part of an intervention to improve clinician-family communication in the ICU that has been shown to significantly reduce family symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder 3 months after the patient's death.17

Figure 2.

VALUE mnemonic for improving clinician-family communication in the ICU.

Discussing Prognosis

Physicians have an important responsibility to share prognoses with patients and their families. However, studies4,45,46 suggest that many physicians do not discuss prognosis directly; and when they do, there is considerable variability in how this is done. There are limited data to guide discussion of prognosis in the ICU, but it is interesting that physicians in ICU family conferences are more likely to discuss prognosis for quality of life than they are to discuss prognosis for survival.45 This finding suggests that physicians find prognosis for quality of life more relevant to family members and highlights the importance of research to identify prognosis for quality of life.

Expert recommendations can help guide discussions of prognosis and suggest that numeric expressions of risk, (eg, “90% of people as sick as your mother do not survive”) generally lead to better comprehension than do qualitative expressions of risk (eg, “your mother is very unlikely to survive”).47 Moreover, since prognostic information applies to outcomes of groups of patients, experts recommend that prognostic information be framed as outcomes for populations rather than as individual outcomes (eg, “out of a group of 100 patients like your mother, I would expect about 90 would not survive this”).48 Some experts also recommend describing both the probability of death as well as the probability of survival to improve understanding. Patients' willingness to consent to life-sustaining treatment declines substantially as the chances for death or severe functional impairment increase.49,50 Therefore, clear, empathic disclosure of prognosis is especially important as the prognosis worsens.

Importance of Interdisciplinary Involvement in Family Conferences

In observational studies, better interdisciplinary communication among nurses and physicians is associated with a number of important outcomes in critical care, including increased patient survival, decreased length of stay, and decreased readmission rates.51-55 Better nurse-physician communication has also been associated with higher patient satisfaction56-58 and lower rates of ICU nurse and physician burnout.59,60 These studies highlight the importance of improving interdisciplinary communication as a mechanism for improving patient outcomes. Improved interdisciplinary collaboration is also associated with decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression among family members and therefore is likely an important component of communication with the family.16

End-of-life care in most settings is delivered by an interdisciplinary team that includes nurses, physicians, and other clinicians.61 Patients and families report that interdisciplinary communication is a key component of good end-of-life care.62,63 Furthermore, most studies of interventions that improved end-of-life care in the ICU explicitly included an interdisciplinary intervention.38,64-66 In the randomized trial of proactive communication with family members using the VALUE strategy and a bereavement pamphlet, the intervention resulted in more nurses attending ICU family conferences and speaking more during these conferences.17

Spirituality and Cross-Cultural Communication

Assessing family members' spiritual needs and offering spiritual care is an important component of care for the family of critically ill patients. Family satisfaction with ICU care is higher if the spiritual care needs of family members are assessed and if spiritual care is provided by a spiritual care provider such as a hospital chaplain.67,68 Critical care clinicians should not attempt to provide spiritual care, but should routinely assess patient and family desire for spiritual care and refer to spiritual care providers.69,70

Communication with family of critically ill patients is challenging even when clinicians, patients, and family members are from the same culture. When this communication occurs across cultures, there are often more opportunities for miscommunication and mistrust. Recommendations for enhancing cultural competency in health-care communication include exploring cultural beliefs; focusing on building trust rather than decision making about a specific treatment; addressing communication and language barriers to assure good bidirectional understanding between clinicians and family members; explicitly discussing spirituality and religion and the role they play in end-of-life care preferences and decision making; and involving extended family and religious or community leaders.71

When cross-cultural communication occurs in the setting of family members who do not speak the same language as clinicians, this adds considerably to the complexity of this communication. Use of professional medical interpreters has been associated with improved outcomes.72 However, even with professional medical interpreters, errors in communication during ICU family conferences are common and may interfere with understanding, decision making, and emotional support.73 Family members in interpreted ICU family conferences are less likely to receive basic emotional support from clinicians than family in conferences where all participants speak the same language.74 A number of suggestions can be made based on a qualitative study examining the perspectives of professional medical interpreters on end-of-life communication.75 Clinicians should try to meet briefly with the interpreters prior to the family conference to help prepare the interpreter and allow them to provide the clinicians with information about the patient, family or culture. Clinicians could also consider meeting with the interpreter following the conference to allow for debriefing. In addition, interpreters should be asked to explicitly state when they are providing a strict linguistic interpretation and when they are providing cultural mediation or interjecting their own suggestions or comments in an effort to enhance understanding in a cross-cultural setting.

The Importance of Protocols and Quality Improvement for Improving Communication

One important feature of the interventions that have been shown to improve clinician-family communication in the ICU is that the interventions were all “proactive” and that a protocol or standardized procedure ensured that communication with family occurred earlier in the ICU course than usual care.17,38,64-66,76 Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that some type of ICU protocol or procedure is likely a necessary component to replicate the successes seen in these studies. At the same time, it is also essential that communication be conducted in a way that is adapted to the needs of individual patients and family members. Communication cannot become protocolized to the point of being robotic and missing the opportunity to respond to individual needs. It is possible to develop protocols or manuals for a communication intervention that allow rigorous evaluation of a standardized intervention but also allow the communication to respond to the needs of the individual.77 It is also important to allow individual clinicians to use their intuition and individual communication styles to respond in ways that are authentic.

Another area of great potential for improving communication with families in the ICU is the use of local quality improvement efforts focused on communication or palliative care. There have been several efforts to develop chart-based quality measures to assess and guide communication with families, and these have great potential.78,79 There has also been a multifaceted quality improvement project that has been associated with a reduction in ICU length of stay for patients who die as well as improved nursing ratings of the quality of dying and a trend toward improved family ratings.80,81

Billing and Reimbursement for Communication With Family Members in the United States

If we are to maximize the effectiveness of clinician-family communication in the ICU, it will be important that critical care clinicians be reimbursed for this activity. In the United States, reimbursement for critical care professional services is time-based and current Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidelines allow physicians to bill for time spent communicating with family members provided the following criteria are met: first, the patient does not have decision-making capacity and cannot participate in medical decision making; second, the physician is on the floor or unit while communicating with families (by telephone or in person); and third, the focus of the discussion bears directly on patient management and medical decision making.82-84 This discussion can include obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient's condition or prognosis, and discussing treatments, provided this discussion has a direct bearing on patient management or medical decision making.82-84 Since most critically ill patients do not have decisional capacity and since the family of critically ill patients are commonly acting as surrogate decision makers, these criteria are often met during ICU family conferences and other communication with family members. Furthermore, communication with family members that helps to prepare them to participate in shared decision making should also be included. However, these criteria mean that time spent providing emotional support and counseling to family members regarding their own emotions or concerns and that is not directly related to helping families participate in shared decision making cannot be billed under the current critical care codes. Such support for family members should also be easily reimbursable given the proven value of this support for reducing the burden of psychological symptoms among family members,17 but it is not in the current system. Table 3 outlines the documentation recommended in order to bill for time spent in an ICU family conference.

Table 3.

Recommended Documentation for an ICU Family Conference in Order to Bill as Critical Care Professional Services in the United States*

| Documentation Element | Examples |

|---|---|

| Underlying reason that patient unable to participate in medical decision making | Patient intubated and sedated |

| Patient delirious | |

| Patient unconscious | |

| Need for discussion | Need to obtain medical history to inform decision making |

| Need to make a decision about provision of a specific treatment | |

| Details of discussion as related to obtaining needed history or making a specific treatment decision or decisions | Family member provided needed medical history |

| Prognosis discussed | |

| Specific treatment options discussed | |

| Specific treatment decisions made |

From Mulholland.83

In practice, because the time-based current procedural terminology code for critical care offers the same reimbursement for any amount of time from 30 to 74 min, time spent communicating with family only adds to the reimbursement if this time pushes the total time > 30 min or > 74 min. However, this feature of time-based reimbursement is true for all components of critical care.

Summary

Critical care is complex, and high-quality critical care requires extensive training, collaboration of a well-functioning interdisciplinary team, implementation of protocols that ensure high levels of adherence to processes of care that are associated with improved outcomes, and adaptation of this care to the needs of the individual. In this way, communication with family members is no different than other aspects of critical care and will require training, interdisciplinary team-work, and implementation of effective and flexible protocols to achieve the best possible outcomes. We are beginning to identify the best ways to accomplish each of these tasks with the ultimate goal of improving the way we communicate with and care for critically ill patients and their families.

Abbreviation

- VALUE

value, acknowledge, listen, understand, elicit

Footnotes

Funding was provided by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR-05226). Dr. White is supported by an National Institutes of Health Career Development Award (KL2RR024130).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Prendergast TJ, Luce JM. Increasing incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:15–20. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hickey M. What are the needs of families of critically ill patients? A review of the literature since 1976. Heart Lung. 1990;19:401–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3044–49. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White DB, Braddock CH, III, Bereknyei S, et al. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:461–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. Supporting family care-givers at the end of life: “they don't know what they don't know.”. JAMA. 2004;291:483–491. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care; Intensive Care Med; Brussels, Belgium. April 2003; 2004. pp. 770–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF, et al. The impact of serious illness on patients' families: SUPPORT Investigators; Study To Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA. 1994;272:1839–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.23.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, et al. Assistance from family members, friends, paid care givers, and volunteers in the care of terminally ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:956–963. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langa KM, Vijan S, Hayward RA, et al. Informal caregiving for diabetes and diabetic complications among elderly Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:S177–S186. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.s177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould DA, et al. When the caregiver needs care: the plight of vulnerable caregivers. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:409–413. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White DB, Curtis JR, Wolf LE, et al. Life support for patients without a surrogate decision maker: who decides? Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:34–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cochrane JJ, Goering PN, Rogers JM. The mental health of informal caregivers in Ontario: an epidemiological survey. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:2002–2007. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289:2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donelan K, Hill CA, Hoffman C, et al. Challenged to care: informal caregivers in a changing health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:222–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, et al. Family caregiving in hospice: effects on psychological and health functioning among spousal caregivers of hospice patients with lung cancer or dementia. Hosp J. 2001;15:1–18. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.2000.11882959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegel K, Raveis VH, Houts P, et al. Caregiver burden and unmet patient needs. Cancer. 1991;68:1131–1140. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910901)68:5<1131::aid-cncr2820680541>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegel K, Raveis VH, Mor V, et al. The relationship of spousal caregiver burden to patient disease and treatment-related conditions. Ann Oncol. 1991;2:511–516. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine C, Zuckerman C. The trouble with families: toward an ethic of accommodation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:148–152. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-2-199901190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association Physicians and family caregivers: a model for partnership. JAMA. 1993;269:1282–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American Academy of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulmasy DP, Terry PB, Weisman CS, et al. The accuracy of substituted judgment in patients with terminal diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:621–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by partnership in making decisions about treatment? BMJ. 1999;319:780–782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quill TE, Brody H. Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: finding a balance between physician power and patient choice. Ann Intern Med. 1996;25:763–769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-9-199611010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267:2221–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torke AM, Alexander GC, Lantos J, et al. The physician-surrogate relationship. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1117–1121. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. Decision-making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtis JR, Burt RA. Point: the ethics of unilateral “do not resuscitate” orders: the role of “informed assent.”. Chest. 2007;132:748–751. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0745. discussion 55–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wall RJ, Curtis JR, Cooke CR, et al. Family satisfaction in the ICU: differences between families of survivors and non-survivors. Chest. 2007;132:1425–1433. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1138–1146. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis JR, Rubenfeld GD. Improving palliative care for patients in the intensive care unit. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:840–854. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the ICU: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1484–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;43:1679–1685. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218409.58256.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selph RB, Shaing J, Engelberg RA, et al. Empathy and life support decisions in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1311–1317. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.West HF, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Expressions of nonabandonment during the intensive care unit family conference. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:797–807. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Prognostication during physician-family discussions about limiting life support in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:442–448. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254723.28270.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. The language of prognostication in intensive care units. Med Decis Making. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0272989X08317012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745–748. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomson R, Edwards A, Grey J. Risk communication in the clinical consultation. Clin Med. 2005;5:465–469. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.5-5-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, et al. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santilli S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients' preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:545–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, et al. Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1991–1998. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baggs JG, Ryan SA, Phelps CE, et al. The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1992;21:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. An evaluation of outcome from intensive care in major medical centers. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:410–418. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-3-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shortell SM, Zimmerman JE, Rousseau DM, et al. The performance of intensive care units: does good management make a difference? Med Care. 1994;32:508–525. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zimmerman JE, Shortell SM, Rousseau DM, et al. Improving intensive care: observations based on organizational case studies in nine intensive care units: a prospective, multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1443–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mitchell PH, Armstrong S, Simpson TF, et al. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Demonstration Project: profile of excellence in critical care nursing. Heart Lung. 1989;18:219–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larrabee JH, Ostrow CL, Withrow ML, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with inpatient hospital nursing care. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:254–268. doi: 10.1002/nur.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kramer M, Schmalenberg C. Securing “good” nurse/physician relationships. Nurs Manage. 2003;34:34–38. doi: 10.1097/00006247-200307000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:686–692. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.The Hospice and Palliative Medicine National Consensus Guidelines. 2004 Available at: www.nationalconsensusproject.org. Accessed June 17, 2007.

- 62.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, et al. Understanding physicians' skills at providing end-of-life care: perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carline JD, Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, et al. Physicians' interactions with health care teams and systems in the care of dying patients: perspectives of dying patients, family members, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123:266–271. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD. Impact of ethics consultations in the intensive care setting: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3920–3924. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200012000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, et al. Spiritual care of families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1084–1090. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259382.36414.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gries CJ, Curtis JR, Wall RJ, et al. Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision making in the ICU. Chest. 2008;133:704–712. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lo B, Ruston D, Kates LW, et al. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life: a practical guide for physicians. JAMA. 2002;287:749–754. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chambers N, Curtis JR. The interface of technology and spirituality in the ICU. In: Curtis JR, Rubenfeld GD, editors. Managing death in the intensive care unit: the transition from cure to comfort. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2001. pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kagawa-Singer M, Blackhall LJ. Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: “You got to go where he lives.”. JAMA. 2001;286:2993–3001. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baker DW, Hayes R, Fortier JP. Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Med Care. 1998;36:1461–1470. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pham K, Thornton JD, Engelberg RA, et al. Alterations during medical interpretation of ICU family conferences that interfere with or enhance communication. Chest. 2008;134:109–116. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, et al. Families with limited English proficiency receive less information and support in interpreted ICU family conferences. Crit Care Med. 2008 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181926430. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Norris WM, Wenrich MD, Nielsen EL, et al. Communication about end-of-life care between language-discordant patients and clinicians: insights from medical interpreters. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1016–1024. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiner JS, Arnold RM, Curtis JR, et al. Manualized communication interventions to enhance palliative care research and training: rigorous, testable approaches. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:371–381. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(suppl):S404–S411. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, et al. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: a practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:264–271. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: description of an intervention. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(suppl):S380–S387. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237045.12925.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:269–275. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Current procedural terminology. 4th ed. American Medical Association; Chicago, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mulholland M. Critical care professional services. In: Manaker S, Krier-Morrow D, Pohlig C, editors. Coding for chest medicine 2008. American College of Chest Physicians; Northbrook, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Critical care visits and neonatal intensive care (codes 99291–99292): Medicare learning network matters, No. mm5993. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Baltimore, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]