Abstract

Background

About half of the 5 million heart failure patients in the United States have diastolic heart failure (clinical heart failure with normal or near normal ejection fraction). Except for candesartan, no drugs have been tested in randomized clinical trials in these patients. Although digoxin was tested in an appreciable number of diastolic heart failure patients in the Digitalis Investigation Group ancillary trial, detailed findings from this important study has not been previously published.

Methods and Results

Ambulatory chronic heart failure patients (N=988) with normal sinus rhythm and ejection fraction >45% (median, 53%) from the US and Canada (1991–1993) were randomly assigned to digoxin (n=492) or placebo (n=496). During 37 months of mean follow up, the primary combined outcome of heart failure hospitalization or heart failure mortality was experienced by 102 (21%) patients in the digoxin group and 119 (24%) patients in the placebo group (hazard ratio=0.82; 95% confidence interval=0.63–1.07; p=0.136). Digoxin had no effect on all-cause, or cause-specific mortality, or all-cause or cardiovascular hospitalization. Use of digoxin was associated with a trend toward reduction in hospitalizations due to worsening heart failure (hazard ratio=0.79; 95% confidence interval=0.59–1.04; p=0.094), but also a trend toward an increase in hospitalizations for unstable angina (HR=1.37; 95% CI=0.99–1.91; p=0.061).

Conclusions

In ambulatory patients with mild to moderate diastolic heart failure and normal sinus rhythm, receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and diuretics, digoxin had no effect on natural history endpoints such as mortality and all-cause or cardiovascular hospitalizations.

Keywords: Digoxin, Diastolic Heart Failure, Morbidity, Mortality

There are an estimated 5 million heart failure (HF) patients in the United States.1 About half of these patients have diastolic HF, defined as clinical HF with normal or near normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF),2 and this group has substantial morbidity and mortality.1, 3–6 Despite this high prevalence of diastolic HF, except for the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM)-Preserved trial, these patients have generally been excluded from randomized HF trials.7

Digitalis glycosides have been used in HF for over two centuries, are inexpensive, and have been extensively studied in systolic HF.8 The role of digoxin in patients with diastolic HF was evaluated in the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) ancillary trial, which was conducted in parallel with the main DIG trial.9–12 The objective of the DIG ancillary trial was to assess the effect of digoxin on the primary combined outcome of HF hospitalization or HF mortality. We analyzed a public-use copy of the DIG dataset obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and present the full results of the ancillary DIG trial, which have not previously been reported.

Methods

Study Design

The DIG trial was a randomized clinical trial, sponsored by the NHLBI, the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies, and Glaxo Wellcome (who supplied the study drug, Lanoxin, and placebo). The purpose of the DIG trial was to evaluate the effects of digoxin on mortality and hospitalizations in ambulatory chronic HF patients with normal sinus rhythm.10 HF patients with LVEF ≤45% (n=6,800) comprised the main trial whereas those with LVEF >45% (n=988) were enrolled in an ancillary study conducted parallel to the main trial. The design and results of the DIG trial have been previously reported.9, 10

Patients

In the DIG ancillary trial, 988 patients with LVEF >45% and normal sinus rhythm at baseline were recruited from the U.S. (186 centers) and Canada (116 centers) between January 1991 and August 1993. Patients received four different daily doses of digoxin or matching placebo (0.125 mg, 0.25 mg, 0.375 mg, and 0.50 mg) based on age, sex, weight, and serum creatinine levels.13 Over 90% of patients were receiving angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and over 80% were receiving diuretics.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in the ancillary DIG trial was the combined endpoint of HF hospitalization or HF mortality. Vital status of all patients was collected up to December 31, 1995 and was 98.9% complete.14 DIG ancillary trial did not pre-specify other secondary outcomes. However, we also studied other outcomes including all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause and cardiovascular hospitalizations. In addition, we also studied the combined outcome of HF hospitalization or cardiovascular mortality, which was the primary outcome in the CHARM-Preserved,7 the only other large randomized clinical trial in diastolic HF. The cause of death or the primary diagnosis leading to hospitalization was classified by DIG investigators who were blinded to the patient’s study-drug assignment.

Statistical Analysis

Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to construct survival plots, and a log-rank statistic was used to compare the survival distributions in the two study groups. To compare the effects of digoxin with that of placebo, we calculated hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) associated with primary and other outcomes using Cox proportional-hazards models. Differences in the number of hospitalizations between groups were estimated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All analyses were repeated for outcomes at two years after randomization. Because the effect of digoxin on outcomes was expected to be more marked in the first two years after randomization, a separate analysis of the effect of digoxin during this period was pre-specified in the DIG protocol.13 All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis with two-sided P values <0.05 considered significant using SPSS for Windows version 13.0.1.

Role of the funding source

Several of the co-authors of the present report (J.L.F, M.G., M.W.R., and J.B.Y.) were investigators in the DIG trial.

Statement of Responsibility

Statistical analyses were conducted by A.A. in collaboration with T.E.L. Fidelity of the raw data was verified by Sean Coady at the NHLBI. The authors had full access to the data and take full responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written

Results

Patient Characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients had a median age of 67 years, 41% were women, 14% were non-white, and 73% had LVEF =>50%. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the 492 patients randomly assigned to digoxin and 496 patients assigned to placebo (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics by treatment group

| Placebo (N=496) | Digoxin (N=492) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 66.9 (±9.9) | 66.7 (±10.7) |

| Ejection fraction (%), mean (±SD) | 55.5 (±8.1) | 55.4 (±8.2) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL), mean (±SD) | 1.26 (±0.39) | 1.25 (±0.39) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/1.73 sq. meter), mean (±SD) | 61.1 (±19.8) | 62.4 (±21.3) |

| Median duration of heart failure, months | 15 | 16 |

| % of patients | ||

| Age ≥ 65 years | 64.5 | 63.2 |

| Women | 40.3 | 42.1 |

| Non-whites | 13.3 | 14.4 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 sq. meter | 52.0 | 48.0 |

| Ejection fraction ≥ 0.50 | 74.4 | 71.1 |

| Method of assessing ejection fraction | ||

| Radionuclide ventriculography | 67.9 | 70.3 |

| Two-dimensional echocardiography | 27.2 | 25.6 |

| Contrast angiography | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >0.55 | 26.4 | 26.8 |

| New York Heart Association functional class | ||

| I | 20.6 | 19.1 |

| II | 56.9 | 59.3 |

| III | 21.0 | 20.7 |

| IV | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| Number of signs or symptoms of heart failure† | ||

| 0 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 2.0 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 6.5 | 6.9 |

| 3 | 11.3 | 8.3 |

| ≥4 | 79.4 | 82.9 |

| Medical history | ||

| Previous myocardial infarction | 49.4 | 49.6 |

| Current angina | 29.2 | 30.3 |

| Diabetes | 30.2 | 27.4 |

| Hypertension | 57.5 | 62.0 |

| Previous digoxin use | 36.3 | 34.1 |

| Primary cause of heart failure | ||

| Ischemic | 56.5 | 56.3 |

| Non-ischemic | 43.5 | 43.7 |

| Hypertensive | 21.0 | 24.0 |

| Idiopathic | 10.7 | 10.4 |

| Others‡ | 11.9 | 9.3 |

| Concomitant medications | ||

| Non-potassium-sparing diuretics | 77.0 | 75.0 |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 8.3 | 7.7 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 86.1 | 86.4 |

| Nitrates | 38.9 | 39.8 |

| Other vasodilators§ | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Daily dose of study medication | ||

| 0.125 mg | 22.6 | 22.4 |

| 0.250 mg | 68.3 | 66.7 |

| 0.375 mg | 7.7 | 10.4 |

| 0.500 mg | 1.4 | 0.6 |

The clinical signs or symptoms studied included râles, elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral edema, dyspnea at rest or on exertion, orthopnea, limitation of activity, S3 gallop, and radiologic evidence of pulmonary congestion.

This category included valvular and alcohol-related causes of heart failure.

These drugs included clonidine hydrochloride, doxazosin mesylate, flosequinan, labetalol hydrochloride, minoxidil, prazosin hydrochloride, and terazosin hydrochloride

Heart Failure Hospitalization or Heart Failure Mortality: The Primary Outcome

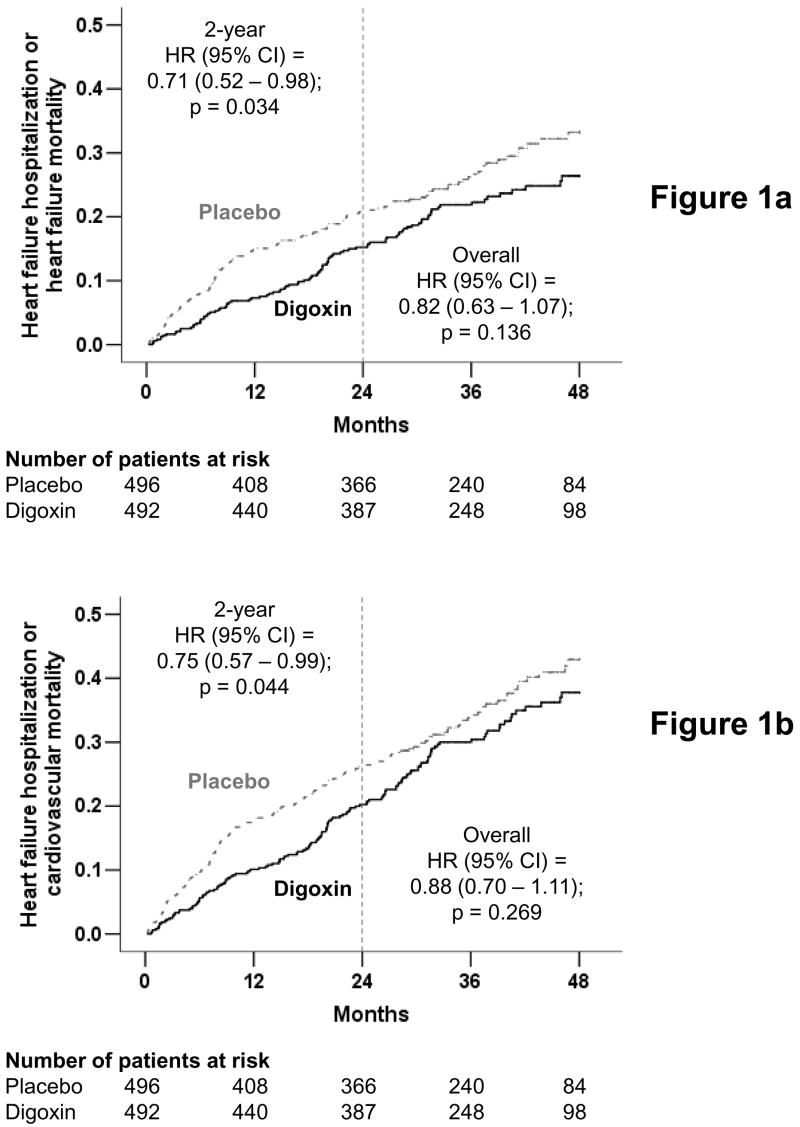

After a mean follow up of 37 months, 102 (21%) patients in the digoxin group and 119 (24%) patients in the placebo group experienced the primary combined outcome of HF hospitalization or HF mortality (HR when digoxin was compared with placebo, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.07; p, 0.136) (Figure 1a and Table 2), which is consistent with the main DIG report.10 During the first two years of follow up after randomization, 67 (14%) patients in the digoxin group and 90 (18%) patients in the placebo group experienced the primary combined outcome (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.98; p, 0.034) (Figure 1a and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots for (a) primary combined outcome of hospitalization due to worsening heart failure or mortality due to heart failure, and (b) combined outcome of hospitalization due to worsening heart failure or mortality due to cardiovascular causes, in diastolic heart failure patients randomized to receive digoxin or placebo (The number of patients at risk at each 12-month interval is shown below the figure)

Table 2.

Mortality and composite endpoints according to randomization to digoxin or placebo

| Placebo (N=496) | Digoxin (N=492) | ARD* | Hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals)† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events at study end: n (%) | % | At 2 years | At study end | ||

| Heart failure hospitalization or heart failure mortality (Primary endpoint) | 119 (24.0%) | 102 (20.7%) | − 3.3% | 0.71 (0.52–0.98); p=0.034 | 0.82 (0.63–1.07); p=0.136 |

| Heart failure hospitalization or cardiovascular mortality (CHARM-Preserved endpoint) | 154 (31.0%) | 142 (28.9%) | − 2.1% | 0.75 (0.57–0.99) p=0.044 | 0.88 (0.70–1.11); p=0.269 |

| Heart failure mortality | 34 (6.9%) | 30 (6.1%) | − 0.8% | 0.88 (0.43–1.80); p=0.718 | 0.88 (0.54–1.43); p=0.598 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 81 (16.3%) | 81 (16.5%) | 0.2% | 0.89 (0.59–1.36); p=0.596 | 1.00 (0.73–1.36); p=0.978 |

| All-cause mortality | 116 (23.4%) | 115 (23.4%) | 0% | 0.88 (0.62–1.25); p=0.480 | 0.99 (0.76–1.28); p=0.925 |

Absolute risk differences (ARD) were calculated by subtracting the percentage of deaths in the placebo group from the percentage of deaths in the digoxin group.

Hazard ratios and confidence intervals were estimated from the Cox proportional-hazards models.

Heart Failure Hospitalization or Cardiovascular Mortality

Hospitalizations due to HF or deaths due to cardiovascular causes, the primary outcomes used in the CHARM-Preserved trial, occurred in 142 (29%) patients in the digoxin group and 154 (31%) patients in the placebo group (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70 to 1.11; p, 0.269) (Figure 1b and Table 2). At two years after randomization, compared with 113 (23%) patients in the placebo group, 89 (18%) patients in the digoxin group experienced HF hospitalizations or cardiovascular mortality (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.99; p, 0.044) (Figure 1b and Table 2).

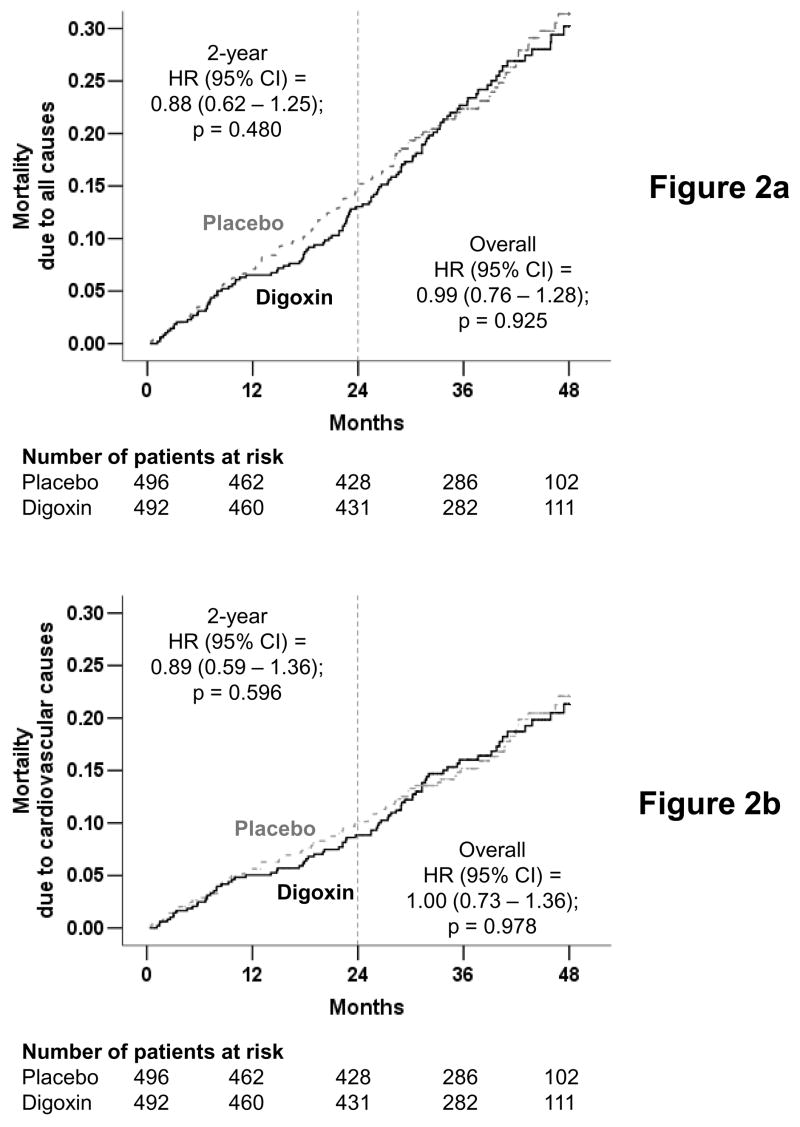

Effect of Digoxin on Mortality

There were 115 deaths from all causes in the digoxin group (23%) and 116 deaths in the placebo group (23%) during the study (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.28; p, 0.925) (Figure 2a and Table 2). There were 30 deaths due to HF among patients randomized to receive digoxin (6%) and 34 deaths (7%) from the same cause among patients randomized to receive placebo (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.54 to 1.43; p, 0.598) (Figure 2b and Table 2). There was no difference in mortality due to cardiovascular causes (81 in each group; HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.36; p, 0.978) (Figure 2c and Table 2). Effects of digoxin on mortality from various causes at two years are displayed in Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c, and Table 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots for mortality due to (a) all causes, (b) cardiovascular causes, and (c) heart failure, in diastolic heart failure patients randomized to receive digoxin or placebo (The number of patients at risk at each 12-month interval is shown below the figure)

Effect of Digoxin on Hospitalization

Hospitalization due to worsening HF occurred in 89 (18%) patients randomized to digoxin and 108 (22%) patients randomized to placebo (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.04; p, 0.094) (Figure 3c and Table 3). During the first two-years of the study, 59 patients randomized to digoxin (12%) and 86 patients randomized to placebo (17%) were hospitalized due to worsening of HF (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.91; p, 0.012) (Figure 3c and Table 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plots for hospitalization due to (a) all causes, (b) cardiovascular causes, and (c) worsening heart failure, in diastolic heart failure patients randomized to receive digoxin or placebo (The number of patients at risk at each 12-month interval is shown below the figure)

Table 3.

Hospitalizations in patients randomized to digoxin or placebo, by causes for hospitalization*

| Placebo (N=496) | Digoxin (N=492) | ARD† | Hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals)‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events at study end: n (%) | % | At 2 years | At study end | ||

| All-cause | 330 (66.5%) | 332 (67.5%) | 1 | 1.06 (0.89–1.25); P=0.533 | 1.03 (0.89–1.20); P=0.683 |

| Cardiovascular | 225 (45.4%) | 241 (49.0%) | 3.6 | 1.08 (0.88–1.32); P=0.456 | 1.10 (0.92–1.32); P=0.301 |

| Worsening heart failure | 108 (21.8%) | 89 (18.1%) | −3.7 | 0.66 (0.47–0.91); P=0.012 | 0.79 (0.59–1.04); P=0.094 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia, cardiac arrest | 5 (1%) | 8 (1.6%) | 0.6 | 1.67 (0.40–6.98); P=0.484 | 1.60 (0.52–4.89); P=0.410 |

| Supraventricular arrhythmia§ | 31 (6.3%) | 32 (6.5%) | 0.2 | 0.92 (0.52–1.62); P=0.775 | 1.04 (0.63–1.70); P=0.881 |

| Atrioventricular block, bradyarrhythmia | 2 (0.4%) | 6 (1.2%) | 0.8 | 6.06 (0.73–50.37); P=0.095 | 3.03 (0.61–15.02); P=0.174 |

| Suspected digoxin toxicity | 3 (0.6%) | 9 (1.8%) | 1.2 | 8.12 (1.02–64.90); P=0.048 | 3.05 (0.83–11.26); P=0.095 |

| Myocardial infarction | 22 (4.4%) | 32 (6.5%) | 2.1 | 1.25 (0.65–2.42); P=0.500 | 1.46 (0.85–2.51); P=0.173 |

| Unstable angina | 62 (12.5%) | 82 (16.7%) | 4.2 | 1.76 (1.20–2.59); P=0.004 | 1.37 (0.99–1.91); P=0.061 |

| Stroke | 24 (4.8%) | 21 (4.3%) | − 0.5 | 0.61 (0.29–1.28); P=0.192 | 0.86 (0.48–1.55); P=0.625 |

| Coronary revascularization¶ | 15 (3.0%) | 17 (3.5%) | 0.5 | 1.10 (0.47–2.60); P=0.823 | 1.14 (0.57–2.29); P=0.706 |

| Cardiac transplantation | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.0 | – – – | 0.99 (0.62–15.84); P=0.995 |

| Other cardiovascular** | 57 (11.5%) | 66 (13.4%) | 1.9 | 1.25 (0.82–1.90); P=0.298 | 1.18 (0.83–1.69); P=0.353 |

| Respiratory infection | 46 (9.3%) | 33 (6.7%) | − 2.6 | 0.60 (0.33–1.09); P=0.094 | 0.70 (0.45–1.10); P=0.120 |

| Other non-cardiac and nonvascular | 196 (39.5%) | 194 (39.4%) | − 0.1 | 1.06 (0.84–1.32); P=0.647 | 1.00 (0.82–1.22); P=0.970 |

| Unspecified | 5 (1%) | 2 (0.4%) | − 0.6 | 0.33 (0.04–3.21); P=0.342 | 0.39 (0.08–2.03); P=0.266 |

| Number of hospitalizations | 949 | 985 | |||

Data shown include the first hospitalization of each patient due to each cause.

Absolute differences were calculated by subtracting the percentage of patients hospitalized in the placebo group from the percentage of patients hospitalized in the digoxin group.

Hazard ratios and confidence intervals (CI) were estimated from a Cox proportional-hazards models that used the first hospitalization of each patient for each reason.

This category includes atrioventricular block and bradyarrhythmia.

This category includes coronary-artery bypass grafting and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

This category includes embolism, venous thrombosis, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, other vascular surgery, cardiac catheterization, other types of catheterization, pacemaker implantation, installation of automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator, electrophysiologic testing, transplant-related evaluation, nonspecific chest pain, atherosclerotic heart disease, hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, and valve operation.

Hospital admissions due to cardiovascular causes occurred in 241 (49%) patients in the digoxin group and 225 (45%) patients in the placebo group (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.32; p, 0.301) (Figure 3b and Table 3). There were no difference in all-cause hospitalizations between the two groups (68% in the digoxin group and 67% in the placebo group; HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.89 to 1.20; p, 0.683) (Figure 3a and Table 3). Among patients who were hospitalized for all causes, 332 in the digoxin group had 985 (median, 2) total hospitalizations for all reasons combined and 330 in the placebo group had 949 (median, 2) such hospitalizations (Wilcoxon test p, 0.811). The effects of digoxin on various causes of hospitalizations at the end of two years of follow up are displayed in Figures 3a, 3b and 3c, and Table 3. Compared with 62 (13%) patients in the placebo group, 82 (17%) patients in the digoxin group were hospitalized due to unstable angina during the study period (HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.91; p, 0.061; Table 3). The effect of digoxin on hospitalizations by various causes are displayed in Table 3.

Adherence to Study Drugs

The median daily dose of the study drug at randomization was 0.25 mg for both the digoxin and placebo groups. Twelve months after randomization, 384 (78%) patients in the digoxin group and 384 (77%) patients in the placebo group were still receiving the study drug. The median daily dose of the study drug at 12 month was 0.25 mg for both treatment groups. Over the entire follow-up period, study drug was discontinued in 323 (33%) patients, of which 159 (32%) were receiving digoxin and 164 (33%) were receiving placebo (p, 0.802). Compared with 53 (11%) patients receiving placebo, 32 (7%) patients receiving digoxin required prescription of open-label digoxin for worsening heart failure or atrial fibrillation (p, 0.019).

Digoxin Toxicity

Overall, 66 (7%) patients were identified by study investigators to have suspected or confirmed digoxin toxicity during routine follow up and 21 (2%) of these occurred during the first two years after randomization. As anticipated, there were more cases of suspected digoxin toxicity in the digoxin group (48 or 10%) than in the placebo group (18 or 4%; p <0.001). Respective numbers of suspected digoxin toxicity during the first two years were: 15 (3.0%) in the digoxin group and 6 (1%) in the placebo group (p =0.049). Among the total of 66 patients with suspected or confirmed digoxin toxicity, only one patient was hospitalized for that reason.

Discussion

The results of the current analysis demonstrate that digoxin had no favorable effect on the natural history of ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate diastolic HF and normal sinus rhythm. Although the results of the DIG ancillary trial were briefly reported in the original DIG publication,10 the results presented in the current analysis provide the first detailed analyses regarding use of digoxin in diastolic HF.

Clinical Importance

These findings are important for several reasons. Diastolic HF comprises up to 50% of all HF patients, and most of these patients are older adults.3–6 Furthermore, with the population aging, the prevalence of diastolic HF is projected to increase disproportionately in the coming decades. Despite better survival compared to patients with systolic HF, older adults with diastolic HF suffer from multiple morbidities and frequent hospitalizations.15, 16 However, diastolic HF patients have traditionally been excluded from clinical HF trials; thus, there are few evidence-based recommendations for these patients.17 Therefore, despite the age of the dataset used in our analysis, the results of the current analysis have contemporary clinical relevance.

Effect of Digoxin on Heart Failure Hospitalization

The effect of digoxin on HF hospitalization in the ancillary DIG trial, though not significant, is comparable to its effect in the main DIG trial and the effect of candesartan in the CHARM-Preserved trial.7, 10 The magnitude of digoxin-associated reduction in HF hospitalization observed in our analysis (HR=0.79; 95% CI=0.59 to 1.04) is similar to those observed in the main DIG trial (HR=0.72; 95% CI=0.66 to 0.79)10 and the CHARM preserved trial (HR=0.85; 95% CI=0.72 to 0.1.01).7 The lack of statistical significance of the effects of digoxin in the ancillary DIG trial is possibly due to small sample size (N=988 in the ancillary DIG trial, about seven times smaller than N=6800 in the main DIG trial and over three times smaller than N=3023 in the CHARM-Preserved trial). In addition, over 75% of participants in the ancillary DIG trial had NYHA class I–II symptoms. Hospitalization due to worsening HF was much lower among these patients than would be expected in diastolic HF patients in clinical practice.16, 18 These relatively low event rates suggest that a larger study or one involving patients at higher risk, such as those with more advanced symptoms, age, or m morbidities, may have resulted in a greater reduction in the primary endpoint by digoxin. Despite the statistical significance of the protocol pre-specified two-year outcomes, and the fact that it was the basis of Food and Drug Administration approval of digoxin for use in HF, the results of the post-hoc analyses of two-year outcomes should be interpreted with caution. This is particularly important as digoxin had no favorable effect on the natural history of patients with HF and normal or near normal LVEF.

An unanticipated finding of the current analysis is that digoxin use was associated with increased risk of hospitalization due to unstable angina, which offset the reduction in HF hospitalization, resulting in no effect on cardiovascular hospitalizations. It is possible that the amount of viable ischemic myocardium in diastolic HF is a larger than that in systolic HF. However, the increased incidence unstable angina did not translate into increased myocardial infarction or mortality.

Comparison with CHARM-Preserved Trial

In the CHARM-Preserved trial (N=3,023), at 37 months of median follow up, hospitalizations due to HF or deaths due to cardiovascular causes, the primary outcomes of that trial, occurred in 333 (22%) patients in the candesartan group and 366 (24%) patients in the placebo group (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.03; p = 0.118).7 In the DIG ancillary trial, on the other hand, during a similar follow up (median, 39 months), 142 (29%) patients in the digoxin group and 154 (31%) patients in the placebo group experienced the same outcomes (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70 to 1.11; p, 0.269) (Figure 1, bottom panel and Table 2).

The primary reason for discontinuation of study drug in CHARM-Preserved was drug-related adverse events, including hypotension, hyperkalemia, or abnormal laboratory values, such as increase in creatinine, which was noted in 18% of patients in the candesartan group (versus 14% in the placebo group; p, 0.001).7 In contrast, the primary reason for discontinuation of study drug in the DIG trial was the use of open-label digoxin due to worsening HF.10, 19 Although 66 (7%) patients were identified to have suspected or confirmed digoxin toxicity, only one of these patients was hospitalized.

Implication for Future Research in Diastolic Heart Failure

Among diastolic HF patients in the DIG trial who received placebo, only 6% patients died from HF, 17% from cardiovascular causes (11% in CHARM-Preserved),7 and overall mortality was 23%. In contrast, among systolic HF patients receiving placebo, 13% patients died from HF, 30% died from cardiovascular causes, and 35% from all causes combined.10 The low HF mortality in diastolic HF should be taken into consideration in planning future clinical trials.15

Clinical Implications: Role of Digoxin in Diastolic Heart Failure

Digitalis is the oldest and one of the least expensive drugs for the management of HF. Digoxin has been historically thought to be contraindicated in patients with diastolic HF, often based on anecdotal reports or non- randomized studies12, 20 The exact mechanistic explanation of how digoxin may exert any potential beneficial effect in diastolic HF (as suggested by the trend in HF hospitalization reduction) is not clearly understood. Although digoxin appears to improve the active energy-dependent early myocardial diastolic function,6, 21 this has not been well studied.12, 22 The effects of digoxin in diastolic HF may be related to its favorable effects on neurohormonal profile.17, 23 It is now known that as in systolic HF, neurohormonal activation is also present in diastolic HF and may contribute to disease progression.24, 25 Recent evidence suggests that digitalis glycosides may reduce sympathetic neurohormonal activity by sensitizing cardiac baroreceptors,26 and suppress renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and reduce renal tubular reabsorption of sodium by inhibiting sodium-potassium ATPase in the kidneys.27, 28 The trend toward increase in hospitalization for unstable angina may be related to reported though not well studied effects of digoxin on platelet and endothelial cell activation.29

Conclusion

In ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate diastolic HF and normal sinus rhythm, receiving ACE inhibitors and diuretics, digoxin use was not associated with any effect on total, cardiovascular or HF mortality, or total or cardiovascular hospitalizations.

Clinicians Perspective

Diastolic heart failure (HF), defined as clinical HF with normal or near normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is common and associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Except for candesartan in the CHARM-Preserved (LVEF>40%), irbesartan in the ongoing I-PRESERVE (LVEF≥45%), and digoxin in the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) ancillary trials, no other drugs have been tested in these patients in randomized trials. The current study reports the detailed analysis of the DIG ancillary trial in which 988 diastolic HF (LVEF>45%) patients in normal sinus rhythm were randomized to receive digoxin or placebo. At 37-month mean follow up, patients receiving digoxin had an 18% lower risk of HF hospitalization or HF mortality, the primary outcome of the study, which was not statistically significant. The effect of digoxin on HF hospitalization or cardiovascular mortality (the primary outcome of CHARM-Preserved), was similar to that of candesartan in CHARM-Preserved (12% and 11% on-significant reductions, respectively). The magnitude of the effect of digoxin on HF hospitalization (21% non-significant reduction; p=0.094) was similar its effect in systolic HF (a 28% significant reduction; p<0.001) and the effect of candesartan in CHARM-Preserved (a 15% non-significant reduction; p=0.072). An unexpected finding was that digoxin use was associated with a non-significant 37% increased risk of hospitalization due to unstable angina (p=0.061). Digoxin had no effect on natural history endpoints such as mortality and all-cause or cardiovascular hospitalizations. Digoxin is an old and inexpensive HF drugs which has been extensively studied in systolic HF. However, little is known about the effect of digoxin in diastolic HF. Currently digoxin is often avoided in diastolic HF based on anecdotal reports or non-randomized studies. The results of this study suggest that although digoxin may reduce HF admissions in ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate diastolic HF receiving ACE inhibitors and diuretics, digoxin does not exert a net beneficial effect on mortality or all-cause or cardiovascular hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

“The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) Investigators. This manuscript has been reviewed by NHLBI for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) publications, and significant comments have been incorporated prior to submission for publication.”

The authors wish to thank the editors and peer-reviewers of Circulation for their excellent comments and recommendations that have significantly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Grant Support

A.A. is supported by a NIH/National Institute on Aging grant 1-K23-AG19211-01.

Footnotes

Contributors

A.A. and M.G. conceived the plan for the detailed analysis of the ancillary DIG trial data presented herein. A.A. prepared the first draft of the manuscript in collaboration with M.G. A.A. analyzed the data, which was verified by T.E.L. All authors interpreted the data, participated in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the article. A.A. obtained the public-use copy of the DIG dataset used in the analysis from the NHLBI and had full access to the data.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Dedication

The authors wish to dedicate this article to the memories of Thomas W. Smith, MD (1936-1997) and Richard Gorlin, MD (1926-1997) who played a crucial role in enhancing our understanding of digoxin in HF and in the planning and conduct of the DIG trial.

Contributor Information

Ali Ahmed, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and VA Medical Center, Birmingham, AL, USA.

Michael W. Rich, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Jerome L. Fleg, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Michael R. Zile, Medical University of South Carolina, and Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center, Charleston, SC, USA.

James B. Young, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland OH, USA.

Dalane W. Kitzman, Wake-Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

Thomas E. Love, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland OH, USA.

Wilbert S. Aronow, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY, USA.

Kirkwood F. Adams, Jr, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Mihai Gheorghiade, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2005 update. Dallas, Texas: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zile MR, Gaasch WH, Carroll JD, Feldman MD, Aurigemma GP, Schaer GL, Ghali JK, Liebson PR. Heart failure with a normal ejection fraction: is measurement of diastolic function necessary to make the diagnosis of diastolic heart failure? Circulation. 2001 Aug 14;104(7):779–782. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.094226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Evans JC, Reiss CK, Levy D. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 Jun;33(7):1948–1955. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R, Shemanski L, Furberg CD, Kitzman DW, Cushman M, Polak J, Gardin JM, Gersh BJ, Aurigemma GP, Manolio TA. Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Oct 15;137(8):631–639. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Jr, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003 Jan 8;289(2):194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure--abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2004 May 6;350(19):1953–1959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003 Sep 6;362(9386):777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gheorghiade M, Adams KF, Jr, Colucci WS. Digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation. 2004;109(24):2959–2964. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132482.95686.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Digitalis Investigation Group. Rationale, design, implementation, and baseline characteristics of patients in the DIG trial: a large, simple, long-term trial to evaluate the effect of digitalis on mortality in heart failure. Control Clin Trials. 1996 Feb;17(1):77–97. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997 Feb 20;336(8):525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Love TE, Lloyd-Jones DM, Aban IB, Colucci WS, Adams KF, Gheorghiade M. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a comprehensive post hoc analysis of the DIG trial. Eur Heart J. 2006 Jan;27(2):178–186. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massie BM, Abdalla I. Heart failure in patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function: do digitalis glycosides have a role? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1998 Jan-Feb;40(4):357–369. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(98)80053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Digitalis Investigation Group. Protocol: Trial to evaluate the effect of digitalis on mortality in heart failure. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins JF, Howell CL, Horney RA. Determination of vital status at the end of the DIG trial. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24(6):726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed A. Association of diastolic dysfunction and outcomes in ambulatory older adults with chronic heart failure. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005 Oct;60(10):1339–1344. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.10.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed A, Roseman JM, Duxbury AS, Allman RM, DeLong JF. Correlates and outcomes of preserved left ventricular systolic function among older adults hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2002 Aug;144(2):365–372. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.124058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt SA. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 Sep 20;46(6):e1–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogg K, Swedberg K, McMurray J. Heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function; epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Feb 4;43(3):317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Division of Cardio-Renal Drug Products: Joint Clinical Review. New Drug Application 20–405: DIG Study. Original NDA amendment (digoxin for heart failure) Beltsville, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topol EJ, Traill TA, Fortuin NJ. Hypertensive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan 31;312(5):277–283. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501313120504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabbah HN, Stein PD. Pressure-diameter relations during early diastole in dogs. Incompatibility with the concept of passive left ventricular filling. Circ Res. 1981;48(3):357–365. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eichhorn EJ, Alvarez LG, Willard JE, Grayburn PA. Digitalis improves myocardial relaxation in patients with heart failure (abstract) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:254A. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gheorghiade M, Ferguson D. Digoxin. A neurohormonal modulator in heart failure? Circulation. 1991 Nov;84(5):2181–2186. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part II: causal mechanisms and treatment. Circulation. 2002 Mar 26;105(12):1503–1508. doi: 10.1161/hc1202.105290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, Anderson RT, Hundley WG, Marburger CT, Brosnihan B, Morgan TM, Stewart KP. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA. 2002 Nov 6;288(17):2144–2150. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson DW, Berg WJ, Sanders JS, Roach PJ, Kempf JS, Kienzle MG. Sympathoinhibitory responses to digitalis glycosides in heart failure patients. Direct evidence from sympathetic neural recordings. Circulation. 1989 Jul;80(1):65–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torretti J, Hendler E, Weinstein E, Longnecker RE, Epstein FH. Functional significance of Na- K-ATPase in the kidney: effects of ouabain inhibition. Am J Physiol. 1972 Jun;222(6):1398–1405. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.222.6.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Covit AB, Schaer GL, Sealey JE, Laragh JH, Cody RJ. Suppression of the renin-angiotensin system by intravenous digoxin in chronic congestive heart failure. Am J Med. 1983 Sep;75(3):445–447. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chirinos JA, Castrellon A, Zambrano JP, Jimenez JJ, Jy W, Horstman LL, Willens HJ, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ, Ahn YS. Digoxin use is associated with increased platelet and endothelial cell activation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2005 May;2(5):525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]