Abstract

The synthesis and evaluation for iNKT stimulation of α-S-galactosylceramide is reported. Prepared by alkylation of a galactosylthiol, this analog of the potent immunostimulatory agent, KRN7000, did not stimulate iNKT cells either in vitro or in vivo.

Invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells are potent regulatory T cells that have been shown to either initiate or shut down a wide range of immune responses.1 A variety of bacteria, viruses and parasites have been demonstrated to trigger the anti-infective activity of iNKT cells,2 and iNKT cells have also been implicated in anti-tumor responses.3 In the absence of microbial or neoplastic triggers, it appears that iNKT cells may regulate the immune system in such a way as to prevent autoimmunity.4 A little more than a decade ago it was revealed that glycolipids, particularly α-galactosylceramides (α-GalCers), could activate iNKT cells by a pathway involving their binding to a class of antigen presenting protein, CD1d.5 This discovery has sparked intense efforts to understand the CD1d pathway of iNKT cell activation and to harness it for therapeutic purposes.6

A synthetic α-GalCer, KRN7000 (Figure 1), has been an invaluable tool for dissecting the function of CD1d activated iNKT cells. For example, the use of KRN7000 as a specific agonist for in vivo stimulation has provided evidence suggesting that NKT cell-mediated pathways may be used to inhibit hepatitis B virus replication7 or protect against cancer,5 diabetes,8 malaria9 and tuberculosis.10 Not surprisingly, considerable effort has been spent on structure/activity investigations. These studies have more recently been aided by crystal structures of ligand-bound mouse11 -and human12-CD1d and even more recently by the report of a ternary structure of human iNKT T cell receptor (TCR)/CD1d/KRN7000.13

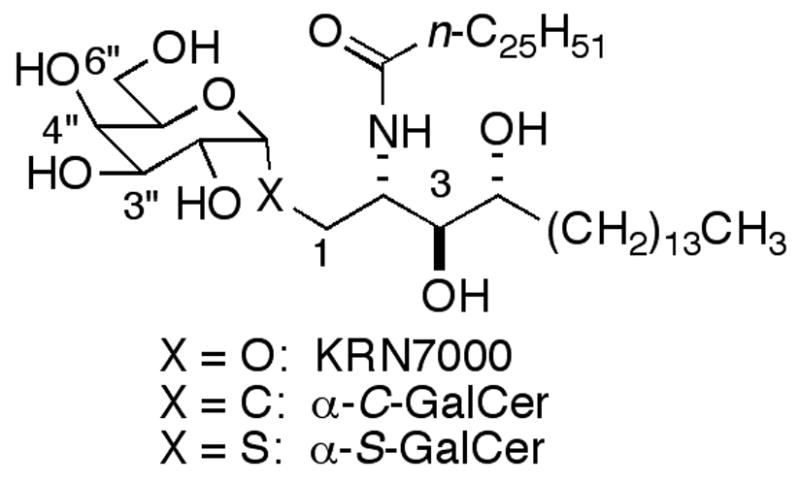

Figure 1.

KRN7000, α-C-GalCer and α-S-GalCer.

One key compound to emerge from SAR investigations is α-C-GalCer (Figure 1).14 Part of the reason it has inspired so much interest is its superiority to KRN7000 in murine model cure ratios for malaria (1000/1 α-C-GalCer/KRN7000) and melanoma (100/1)15 and for eradication of tumors in mice.16 The strong activity of α-C-GalCer is not well understood. Both human and mouse CD1d/glycolipid binary structures show a hydrogen bond between CD1d and the anomeric oxygen of the bound α-GalCers (this hydrogen bond is not present in the ternary iNKT TCR/CD1d/KRN7000 complex). Consequently, it would be anticipated that the stability of the complex of α-C-GalCer, lacking an anomeric oxygen, with CD1d would be decreased and that this might result in less NKT cell proliferation and lower cytokine production. Since this is not the case, it is apparent that, even with the information provided by the crystal structures and prior SAR studies, it can still be difficult to predict how structural modifications will affect stimulatory properties. The results with α-C-GalCer suggest that looking at other anomeric replacements would be relevant. Herein we report the synthesis and evaluation of α-S-GalCer as an activator of NKT cells. Just prior to the submission of this manuscript a synthesis of α-S-GalCer was reported online,17 but no biological data was given.18

S-Glycosides have been used as replacements for O-glycosides because of their similar conformational preferences about the anomeric bonds19 and because of the lower susceptibility of thioglycosides to enzymatic cleavage.20 Although a C-S bond is longer than a C-O bond, the C-S-C bond angle is significantly smaller than the C-O-C angle, which results in relatively small differences between the positions of the atoms along the glycosidic linkage. However, S-glycosides have substantially more flexibility because of the longer bonds and weaker stereoelectronic effects.

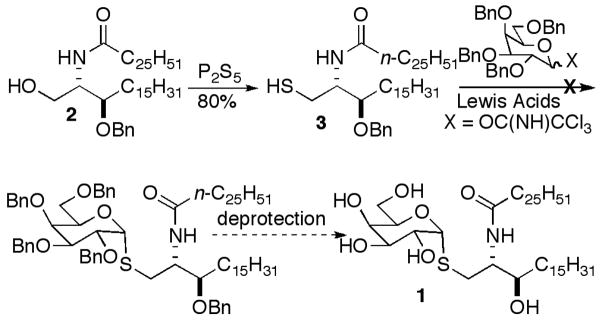

Our initial target was α-S-GalCer 1, since we had ceramide 2 in hand, and we had demonstrated that sphinganine-containing α-GalCers showed similar iNKT cell stimulation in murine models to the corresponding phytosphingosine-containing α-GalCers.21 Thiol ceramide 3 was prepared in a straightforward fashion by treatment of 2 with P2S5 (Scheme 1).22 There was no literature precedent for α-glycosylation with such a complex thiol acceptor. Most α-glycosides prepared with thiol acceptors have employed simple alkylthiols or thiophenols and have used trichloroacetimidates23 that can be activated with Lewis acids. With 3 no glycosylation resulted in attempted coupling with a galactosyl trichloroacetimidate. Consequently, we decided to examine a substitution reaction using a thioglycoside nucleophile.

Scheme 1.

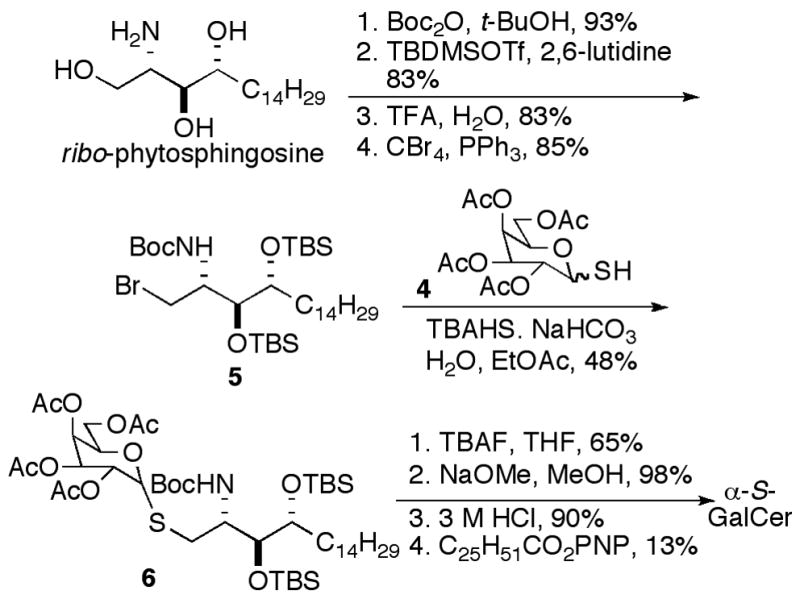

To examine a substitution approach thiol sugar 4 and a brominated derivative 5 of ribo-phytosphingosine were prepared. Thiol-monosaccharide 4 was prepared in three steps as an inseparable anomeric mixture, as described by Yamamoto et al.24 ribo-Phytosphingosine was converted to 5 in four steps, as shown in Scheme 2. Schmidt’s procedure for the synthesis of α-linked thioglycopeptides was employed for the substitution reaction,25 and the anomers were separable at this stage. Attempted one-pot cleavage of the Boc and silyl groups of 6 with TFA left one silyl group intact; so the silyl groups were first cleaved with TBAF. Easier purifications were realized when the acetates were cleaved prior to Boc-deprotection. Boc-deprotection was achieved with HCl, and acylation gave α-S-GalCer. We believe that the low yield in the unoptimized final coupling was a result of the poor solubility of the fully deprotected glycosylated sphingoid base.

Scheme 2.

Activation of iNKT cells with α-GalCer has long been known to potently stimulate rapid cytokine secretion and induce iNKT cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo.26 Since α-C-GalCer is known to be much more potent when used in vivo,15,27 in part due to the activation of NK cells, and other analogues have elicited very different cytokine profiles,28 the ability of α-S-GalCer to induce cytokine secretion and cell proliferation was tested both in vivo and in vitro. To evaluate the ability of α-S-GalCer to activate NKT cells in vivo the lipid was administered i.p. (5 or 10 μg) in PBS 0>05% Tween-20 (200 μg/mL) to NOD and C57Bl/6 mice, and NKT cell frequency and intracellular cytokine expression was determined by FACS analysis. For the in vitro analysis splenocytes were isolated from the same strains, labeled with CFSE, and activated with α-S-GalCer (100 and 200 ng/mL). At 24 and 48 hours the induction of cytokine expression was determined by intracellular staining for IFNγ and cell proliferation by CFSE dilution. Despite the expected similarity between KRN7000 and α-S-GalCer along the glycosidic linkage, α-S-GalCer induced no detectable cytokine or proliferative response. With the complete lack of stimulation we decided to see if any explanation could be deduced by docking α-S-GalCer into the ternary crystal structure.

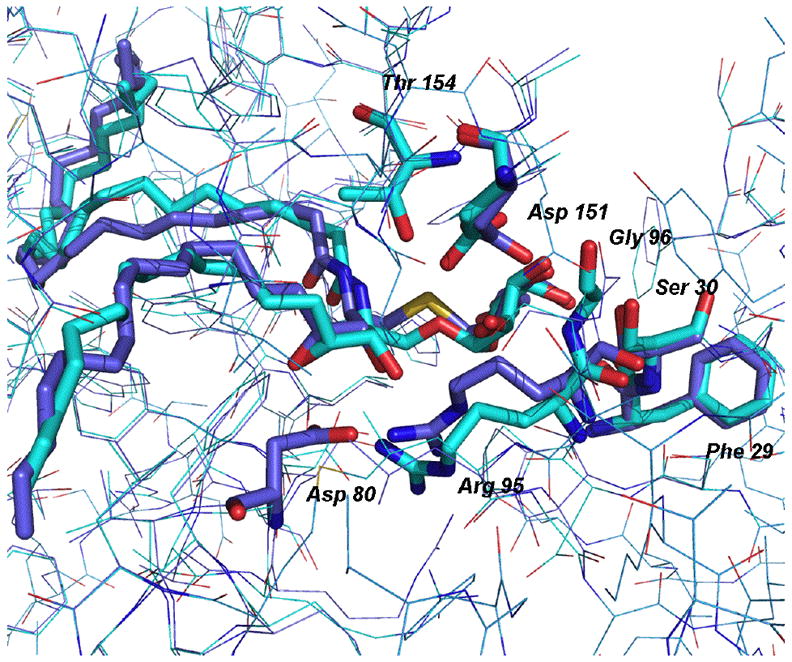

The interactions of α-S-GalCer with CD1d and the NKT TCR were examined by modeling the compound in the ternary crystal structure (PDB 2PO6).13 The anomeric oxygen atom of KRN7000 was replaced with an sp3 hybridized sulfur atom. The resulting α-S-GalCer, along with residues within a 6 Å shell, were minimized for approximately 50,000 iterations (Figure 2). The calculated RMSD between 2PO6 and the minimized structure with α-S-GalCer was 0.12 Å, while the RMSD value between the ligands in these complexes was found to be 1.21 Å. Without the aid of an experimental structure, conclusions regarding the strength of interactions must be carefully interpreted; nevertheless, it appeared that several key hydrogen bonds are conserved between the two complexes, including bonds to Arg 95, Ser 30 and Phe 29 (see Table 1). The complex with α-S-GalCer seems to make an additional hydrogen bond to Asp 80, relative to the complex with KRN7000. However, three key hydrogen bonds formed between KRN7000 and the protein appear to either be absent or weakened in the modeled α-S-GalCer/-protein structure.

Figure 2.

The two molecules, α-S-GalCer (purple) and KRN7000 (cyan) are shown modeled into the ternary complex with CD1d and NKT-TCR. Surrounding amino acids are shown as sticks if they form hydrogen bonds with the molecules (residues are purple if they are in hydrogen bonding distance to α-S-GalCer and cyan for bonds with KRN7000).

Table 1.

| TCR Residue | KRN7000 | α-S-GalCer |

|---|---|---|

| Arg 95 | O3 | O3 |

| Ser 30 | O4″ | O3″d |

| Phe 29 | O4″ | O4″ |

| Asp 80 | ---- | O4 |

| Asp 151 | O2″,O3″ | O3″e |

| Gly 96 | O2″ | ---- |

| Thr 154 | N2 | ---- |

From crystallographic data.

From modeling studies.

For numbering of positions of ligands see Figure 1.

O4″ also within H-bonding distance at 2.91 Å

Loose H-bond.

In the structure with KRN7000, there are two hydrogen bonds involving Asp 151, a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl of Gly 96 and another to the OH of Thr 154. In the α-S-GalCer complex, only one hydrogen bond to Asp 151 is detected; however the other would be possible with a slight shift of Asp 151. There is no hydrogen bond to Gly 96, due to a shift of both the donor and acceptor atoms. In fact, the geometry of α-S-GalCer may prevent the formation of this hydrogen bond. Finally, the hydrogen bond to Thr 154 is weak (3.35 Å) but may be possible with a slight shift of the threonine. From the modeling studies it is not clear why there should be no activation of the iNKT cells by α-S-GalCer. It is likely that the explanation is related to an earlier stage of the iNKT cell activation process. For the in vivo system degradation or oxidation of the α-S-GalCer are possibilities. Even in the in vitro assays, loading of the glycolipid onto CD1d is generally aided by cofactors in the medium.

In summary, unlike KRN7000 and the closely related α-C-GalCer, α-S-GalCer does not stimulate iNKT cells either in vitro or in vivo under standard conditions. Since reasons for the lack of activity are not obvious, we are investigating potential explanations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data, including experimental procedures and characterization data, as well as copies of high-resolution 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds can be found in the online version.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for financial support provided by NIH NIAID (AI057519: ARH; 2RO1 AI 45051 and U19 AI046130: SBW) and JDRF 1-2004-771 to SBW.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Bendelac A, Savage PA, Teyton L. Ann Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Behar SM, Porcelli SA. Curr Top Microbiol Immun. 2007;314:215. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tupin E, Kinjo Y, Kronenberg M. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:405. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Hong C, Park SH. Critical Rev Immun. 27:511. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v27.i6.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Motohashi S, Nakayama T. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:638. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. Trends in Immun. 2007;28:491. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Meyer EH, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Ann Rev Medicine. 2008;59:281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061506.154139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamamura T, Sakuishi K, Illes Z, Miyake S. J Neuroimmun. 2007;191:8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, Ueno H, Nakagawa R, Sato H, Kondo E, Koseki H, Taniguchi M. Science. 1997;278:1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerundolo V, Salio M. Curr Top Microbiol Immun. 2007;314:325. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakimi K, Guidotti LG, Koezuka Y, Chisari FV. J Exp Med. 2000;192:921. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Hong S, Wilson MT, Serizawa I, Wu I, Singh N, Naidenko OV, Miura T, Haba T, Scherer DC, Wei J, Kronenberg M, Koezuka Y, Van Kaer L. Nature Med. 2001;7:1052. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sharif S, Arreaza GA, Zucker P, Mi QS, Sondhi J, Naidenko O, Kronenberg M, Koezuka Y, Delovitch TL, Gombert JM, Leite-De-Moraes M, Gouarin C, Zhu R, Hameg A, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Lepault F, Leheuh A, Bach JF, Herbelin A. Nature Med. 2001;7:1057. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang B, Geng YB, Wang CR. J Exp Med. 2001;194:313. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Falcone M, Facciotti F, Ghidoli N, Monti P, Olivieri S, Zaccagnino L, Bonifacio E, Casorati G, Sanvito F, Sarvetnick N. J Immunol. 2004;172:5908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Hansen DS, Siomos MA, de Koning-Ward T, Buckingham L, Crabb BS, Schofield L. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2588. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Van Kaer L, Bergmann CC, Wilson JM, Schmeig J, Kronenberg M, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Koezuka Y, Tsuji M. J Exp Med. 2002;195:617. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chackerian A, Alt J, Perera V, Behar SM. Inf Immun. 2002;70:6302. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6302-6309.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zajonc DM, Cantu C, III, Mattner J, Zhou D, Savage PB, Bendelac A, Wilson IA, Teyton L. Nature Immunol. 2005;6:810. doi: 10.1038/ni1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch M, Stronge VS, Shepherd D, Gadola SD, Matthew B, Ritter G, Fersht AR, Besra GS, Schmidt RR, Jones EY, Cerundolo V. Nature Immunol. 2005;6:819. doi: 10.1038/ni1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borg NA, Wun KS, Kjer-Nielsen L, Wilce MCJ, Pellicci DG, Koh R, Besra GS, Bharadwaj M, Godfrey DI, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. Nature. 2007;448:44. doi: 10.1038/nature05907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Fujii S-i, Shimizu K, Hemmi H, Fukui M, Bonito AJ, Chen G, Franck RW, Tsuji M, Steinman RM. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604812103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang G, Schmieg J, Tsuji M, Franck RW. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:3818. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmeig J, Yang G, Franck RW, Tsuji M. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1631. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teng MWL, Westwood JA, Darcy PK, Sharkey J, Tsuji M, Franck RW, Porcelli SA, Besra GS, Takeda K, Yagita H, Kershaw MH, Smyth MJ. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dere RT, Zhu X. Org Lett. doi: 10.1021/ol8019555. asap. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyle, F. R. U.S. Patent 6,635,622 B2, 2003 describes α-S-GalCer and reports modest anti-tumor activity (based on a lumphocyte mixed culture reaction and inhibition of metastasis of B16 mouse melanoma cells. Data related to NKT cell stimulation is not given.

- 19.(a) Montero E, Garcia-Herrero A, Asensio JL, Hirai K, Ogawa S, Santoyo-Gonzalez F, Canada FJ, Jimenez-Barbero J. Eur J Org Chem. 2000:1945. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aguilera B, Jimenez-Barbero J, Fernandez-Mayoralas A. Carbohydr Res. 1998;308:19. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(98)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Weimar T, Kreis UC, Andrews JS, Pinto BM. Carbohydr Res. 1999;315:222. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa A, Morita M, Kojima Y, Ishida H, Kiso M. Carbohydr Res. 1991;214:43. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ndonye RM, Izmirian DP, Dunn MF, Yu KOA, Porcelli SA, Khurana A, Kronenberg M, Richardson SK, Howell AR. J Org Chem. 2005;70:10260. doi: 10.1021/jo051147h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrov KA, Andreev LN. Usp Khim. 1969;38:41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Kaesbeck L, Kessler H. Liebigs Ann Org Bioorg Chem. 1997:165. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schmidt RR, Stumpp M. Liebigs Ann. 1983:1249. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto K, Watanabe N, Matsuda H, Oohara K, Araya T, Hashimoto M, Miyairi K, Okazaki I, Saito M, Shimizu T, Kato H, Okuno T. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:4932. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.019. The anomeric ratio for 4 was variable, but the yield shown is based on the α-anomer present. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu X, Schmidt RR. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:875. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. Nature Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuji M. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1889. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6073-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.For example, see: Forestier C, Takaki T, Molano A, Im JS, Baine I, Jerud ES, Illarionov P, Ndonye R, Howell AR, Santamaria P, Besra GS, DiLorenzo TP, Porcelli SA. J Immunol. 2007;178:1415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1415.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data, including experimental procedures and characterization data, as well as copies of high-resolution 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds can be found in the online version.