Abstract

Drug prevention campaigns commonly seek to change outcome expectancies associated with substance use, but the effects of violating such expectancies are rarely considered. This study details an application of the expectancy violation framework in a real world context by investigating whether changes in marijuana expectations are associated with subsequent future marijuana intentions. A cohort of adolescents (N = 1,344; age range = 12-18 years) from the National Survey of Parents and Youth was analyzed via secondary analysis. Nonusers at baseline were assessed 1 year later. Changes in expectancies were significantly associated with changes in intentions (p < .001). Moreover, in most cases, changes in expectancies and intentions had the strongest relationship among those who became users. The final model accounted for 31% of the variance (p < .001). Consistent with laboratory studies, changes in marijuana expectancies were predictive of changes in marijuana intentions. These results counsel caution when describing negative outcomes of marijuana initiation. If adolescents conclude that the harms of marijuana use are not as grave as they had been led to expect, intentions to use might intensify.

Keywords: adolescence, marijuana use, expectancy violations, outcome expectancies, drug prevention

Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug among adolescents (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007). It also is the most common substance reported in adolescents’ emergency department admissions (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2005b). Of 2.1 million individuals who used marijuana for the first time, nearly 60% of them were under the age of 18 (SAMHSA, 2005a). Far from an innocuous indiscretion of the young, heavy marijuana use can impair normal adolescent development (Hall & Solowij, 1998), reduce learning, and decrease mental flexibility (Lundqvist, 2005). Other outcomes include increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases (Boyer, Tschann, & Shafer, 1999), problems at school (Lynskey & Hall, 2000), increased risk of motor vehicle accidents (Smiley, 1999), and lung and bronchial cancers (Sidney, Quesenberry, Friedman, & Tekawa, 1997).

As a rule, marijuana prevention campaigns, even those involving massive expenditures, have enjoyed only moderate success (Atkin, 2002; Hornik, 2002). An evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign (Orwin et al., 2006) revealed that greater Campaign exposure was associated with weaker anti-drug norms and higher rates of marijuana initiation. There are many possible reasons for these effects (Hornik, 2006), including the possibility that the typical campaign often is designed to develop expectancies regarding marijuana use outcomes that may not be experienced by the initiate. Changes in expectancies regarding marijuana, and the effects of such changes on initiates’ intentions to continue use, are the focus of this investigation.

Marijuana Use and Outcome Expectancies

Mounting evidence has suggested that outcome expectancies (expected or anticipated harms and benefits) associated with substance use play a role in the initiation and progression of drug use (Jones, Corbin, & Fromme, 2001). The bulk of research on expectancies and substance use has been concerned with alcohol (e.g., Christiansen, Smith, Roehling, & Goldman, 1989; Stacy, 1995). Jones et al.’s (2001) review revealed that increases in drinking were associated with positive expectancies and inversely associated with negative ones. The expectancy literature concerned with other drugs (e.g., tobacco, marijuana) has mimicked the findings of alcohol studies: Outcome expectancies are predictive of substance usage intentions and behaviors (Boys et al., 1999; Schafer & Brown, 1991).

The present research is focused on the association between changes in adolescents’ expectancies regarding the effects of marijuana and their intentions to use marijuana. Research has explored how anticipated costs and benefits of marijuana usage predict intentions, but the relation of expectancy changes on drug use intentions has not been widely considered. An expectancy change (EC) may occur when a behavior’s outcome comes to be judged as noticeably more—or less—positive than is expected. When an EC occurs, arousal is heightened, attention is focused on the outcome, and a label is attached to the act or outcome. This change of focus may have important implications for prevention programming (Kernahan, Bartholow, & Bettencourt, 2000). Through a multitude of dissemination routes, adolescents learn to expect various negative (or positive) outcomes from marijuana use. We hypothesize a significant relation between changes in marijuana expectancies and changes in intentions to use (Hypothesis 1). If supported, this possibility may have important implications for prevention efforts.

Direct Versus Indirect Experience

This research also provides an opportunity to compare the impact of ECs resulting from direct and indirect experience. Most EC research is conducted in highly controlled contexts. Expectancies are assumed or measured, and respondents are assigned to expectancy confirmation or violation conditions. In designs of this type, there is little question as to the source, or the timing, of the expectancy violation and subsequent change. Outside the laboratory, ECs can occur in a multitude of ways. A change in expectancies can result from direct experience (e.g., an adolescent who expects to lose all friends after smoking marijuana may find that this outcome does not transpire). This experience may change the expectation in a pro-marijuana direction and may magnify intentions to use the substance. Adolescents’ expectations regarding marijuana also may change as a result of many other factors (e.g., vicarious learning). Will indirect changes, too, be associated with usage intentions? It seems reasonable to hypothesize (Hypothesis 2) that ECs that come about as a result of direct experience would be more positively associated with usage intentions than are ECs not arising from direct experience (Craig, 1968; Craig & Wood, 1969). This result would counsel caution when creating prevention messages, as excessive threats may produce readily violated expectancies, paradoxically amplifying rather than attenuating usage intentions.

Method

Respondents

A nationally representative sample of youths was studied in a secondary analysis of longitudinal data drawn from the National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY). The sample in our study consisted of 1,344 adolescents who ranged in age from 12 to 18 years in the 1st year of the research (M = 14.15, SD = 1.52). Male participants constituted 50.4% of the sample, and female participants constituted 49.6% of the sample. The ethnic/racial break-down included 66.5% White, 16.7% African American, 13.3% Hispanic, and 3.5% Asian respondents. All demographic characteristics were weighted to be nationally representative.

Design and Procedure

The NSPY was implemented to assess the effectiveness of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign in reducing substance use among adolescents. NSPY is a national longitudinal household survey of youths 12 to 18 years of age (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2006). Data used for our study were collected from November 1999 to June 2002. Approximately 1 year separated respondents’ first and second round interviews. The sample used in the analyses completed both rounds (N = 1,344). Respondent attrition primarily occurred due to refusal or due to respondents becoming age ineligible (>18 years of age) at Year 2. Written consent from the respondent and his or her parent or guardian was required for participation. Longitudinal sampling weights corrected for national estimates as well as standard error estimates associated with this complex sampling design. Furthermore, application of these sampling weights adjusted for differential respondent attrition that occurred between Years 1 and 2. The software used in the analyses, WesVar 4.2 (Westat, 2000), compensated for these artifacts, ensuring that the results were nationally representative.

The survey was administered in respondents’ homes by using trained interviewers with touch-screen laptop computers. The NSPY questionnaire included measurements of media usage patterns as well as questions regarding respondents’ drug related beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Computer-assisted personal interviewing was used on nonsensitive items. The interviewer read the survey questions and recorded the respondent’s answers. When collecting sensitive data, audio computer-assisted self-interview was used. This allowed respondents to listen to questions via headphones and to input their answers privately on a touch-screen laptop.

Grouping Variable

To classify youths as nonusers or users, respondents were asked, “Have you ever, even once, used marijuana?” Those who responded “yes” to this question were categorized as users; those responding “no” were considered nonusers. For the purposes of this study, only Year 1 nonusers were selected. From this Year 1 cohort, users and nonusers were identified at Year 2.

Dependent Variable: Intentions to Use Marijuana

Behavioral intentions associated with using marijuana were assessed with a two-item composite (α= .73): “How likely is it that you will use marijuana, even once or twice, over the next 12 months?” This first item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (I definitely will not) to 4 (I definitely will). Those who provided a response of 2, 3, or 4 were then asked “How likely is it that you will use marijuana nearly every month for the next 12 months?” The same 4-point scale was used. To ensure that all participants in our sample were included, those who provided a value of 1 to the first item were also coded as 1 for the second item. The reliability coefficient was calculated on this basis of this scaling process.

Expectancy Variables

Five-point Likert-type scales, with response options ranging from very unlikely to very likely, were used for all expectancy items. Physical expectations were assessed with “How likely is it that the following would happen to you if you used marijuana nearly every month over the next 12 months:” followed by the expectation outcome “Damage my brain.” Social expectation outcomes used the same stem with the options “Lose my friends’ respect” and “Have a good time with my friends.” Cognitive expectation outcomes included “Be more creative and imaginative” and “Be acting against my moral beliefs.” Achievement outcomes were “Mess up my life,” “Do worse in school,” and “Lose my ambition.”

Operational Definitions and Analytic Plan Overview

Only respondents who reported never having used marijuana at Year 1 were used for the study. These respondents were categorized as users or nonusers on the basis of Year 2 usage. An EC score (Year 2 - Year 1) was computed for each of the expectancy items. The same technique of calculating change scores was performed for the dependent measure of marijuana intentions. We evaluated statistical assumptions associated with the use of change scores. Most (seven of nine) of the change score variables were normally distributed, even though skewness tests are sensitive to departures from normality when sample size is large (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Across all change scores, the standard deviation ratio of users to nonusers was largely homogenous (Field, 2005; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). In the past, change scores were avoided because of reliability issues. However, as has been shown, change scores can be reliable if there is sufficient variance (i.e., if not all respondents exhibit the same change), and if the correlation between initial status and change is not extreme (see Rogosa & Willet, 1983; Zimmerman & Williams, 1982). The data of the present research satisfy both of these criteria.

Results

Descriptives and Bivariate Tests

At Year 2, 14.5% of the Year 1 nonusing sample became users; 85.5% remained nonusers. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. As an initial test of Hypothesis 1, associations between changes in expectancies and marijuana intentions were examined (Table 2). In the overall sample, all EC variables were correlated with changes in intentions. All of these correlations, which ranged from .14 to .25, were statistically significant (all ps < .001). Also, all EC scores were significantly correlated: values ranged from .06 to .70 (all ps < .05). The magnitude of associations between change in intentions and most expectancy variables was considerably stronger in the user group than in the nonuser group (Table 3). In four of eight comparisons, Z tests of independent correlations disclosed that the relationship between change in expectancy and usage intention was significantly greater in the user group (vs. the nonuser group).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations in Participants’ Responses (N = 1,344) for Items in Year 1 (Y1) and Year 2 (Y2)

| Y1 Nonuser → Y2 Nonuser |

Y1 Nonuser → Y2 User |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 Nonuser |

Y2 Nonuser |

Y1 Nonuser |

Y2 User |

|||||

| Item | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Intentions | 1.06 | 0.26 | 1.14 | 0.35 | 1.29 | 0.42 | 2.01 | 0.84 |

| Damage my braina | 1.72 | 1.15 | 1.71 | 1.16 | 1.93 | 1.22 | 2.5 | 1.26 |

| Lose my friends’ respecta | 1.97 | 1.25 | 2.12 | 1.32 | 2.67 | 1.43 | 3.68 | 1.21 |

| Have a good time with my friends | 2.14 | 1.34 | 2.26 | 1.32 | 2.79 | 1.34 | 3.62 | 1.30 |

| Be more creative and imaginative | 1.76 | 1.19 | 1.85 | 1.13 | 2.22 | 1.33 | 2.74 | 1.29 |

| Be acting against my moral beliefsa | 1.72 | 1.10 | 1.67 | 1.09 | 1.90 | 1.05 | 2.65 | 1.37 |

| Mess up my lifea | 1.57 | 1.08 | 1.64 | 1.08 | 2.06 | 1.23 | 2.57 | 1.36 |

| Do worse in schoola | 1.55 | 1.01 | 1.64 | 1.06 | 1.94 | 1.13 | 2.68 | 1.38 |

| Lose my ambitiona | 1.82 | 1.07 | 1.87 | 1.11 | 2.13 | 1.13 | 2.98 | 1.43 |

Reversed so that higher score represents perceiving marijuana as less harmful.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix for Participants in the Sample (N = 1,344)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Δ Intentions | — | ||||||||

| 2. Δ Damage my braina | .14*** | — | |||||||

| 3. Δ Lose my friends’ respecta | .21*** | .37*** | — | ||||||

| 4. Δ Have a good time with my friends | .15*** | .10*** | .19*** | — | |||||

| 5. Δ Be more creative and imaginative | .14*** | .11*** | .10*** | .43*** | — | ||||

| 6. Δ Be acting against my moral beliefsa | .20*** | .51*** | .45*** | .12*** | .08** | — | |||

| 7. Δ Mess up my lifea | .23*** | .62*** | .46*** | .06* | .09*** | .57*** | — | ||

| 8. Δ Do worse in schoola | .25*** | .57*** | .46*** | .06* | .12*** | .62*** | .70*** | — | |

| 9. Δ Lose my ambitiona | .23*** | .50*** | .52*** | .17*** | .13*** | .59*** | .61*** | .64*** | — |

| M | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| SD | 0.54 | 1.42 | 1.45 | 1.68 | 1.41 | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.33 | 1.35 |

Reversed so that positive change score represents a shift to perceiving marijuana as less harmful.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Correlations Between Δ Expectancies and Δ Intentions by Group Status (N = 1,344)

| Variable | Y1 Nonuser → Y2 Nonuser | Y1 Nonuser → Y2 User | Z testa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Δ Damage my brainb | .06* | .15* | 1.16 |

| Δ Lose my friends’ respectb | .12*** | .17* | 0.66 |

| Δ Have a good time with my friends | .07* | .18** | 1.43 |

| Δ Be more creative and imaginative | .10*** | .14 | 0.52 |

| Δ Be acting against my moral beliefsb | .03 | .35*** | 4.30*** |

| Δ Mess up my lifeb | .13*** | .39*** | 3.60*** |

| Δ Do worse in schoolb | .11*** | .42*** | 4.32*** |

| Δ Lose my ambitionb | .09*** | .32*** | 3.10** |

Test of difference between two independent correlations.

Reversed so that positive change score represents a shift to perceiving marijuana as less harmful.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression

A four-step hierarchical linear multiple regression was conducted to account for the unique variance of each of these variables as well as to test Hypothesis 2. Demographic characteristics of age, gender, and race were controlled at Step 1. At Step 2, all eight EC scores were entered as predictors of change in intention to use marijuana (from Year 1 to Year 2). In Step 3, the grouping variable (user vs. nonuser at Year 2) was entered. Step 4 included the interactions of each of the EC variables with the grouping variable. Interaction terms were computed by multiplying each expectancy variable with the grouping variable. All predictors involved in interaction terms were standardized prior to entry model to minimize problems associated with multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991). All tolerance levels exceeded .33.

Results from the four-step hierarchical multiple regression analysis revealed significant associations of ECs with changes in marijuana intentions. The final model accounted for 31% of the variance, F(22, 1321) = 13.58, p < .001. Results of the regression at each step are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Predicting Δ Intentions (N = 1,344)

| At step |

Final model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ Expectancies | R2 change | Model R2 | Model R | F test | β |

| Step 1: Demographics | .01** | .01** | .10** | ||

| Age | 0.31 | -.02 | |||

| Gender | 0.12 | 0.01 | |||

| Race | |||||

| Black | 2.02 | -.05 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.92 | 0.04 | |||

| Asian | 3.44 | -.03 | |||

| Step 2: Expectancies | .10*** | .11*** | .33*** | ||

| Δ Damage my braina | 3.76 | -.08 | |||

| Δ Lose my friends’ respecta | 2.32 | 0.06 | |||

| Δ Have a good time with my friends | 1.25 | 0.05 | |||

| Δ Be more creative and imaginative | 2.29 | 0.04 | |||

| Δ Be acting against my moral beliefsa | 0.33 | -.04 | |||

| Δ Mess up my lifea | 9.10 | .14** | |||

| Δ Do worse in schoola | 4.58 | .10* | |||

| Δ Lose my ambitiona | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| Step 3: Group Status | .13*** | .24*** | .49*** | ||

| Groupb | 45.20 | .28*** | |||

| Step 4: Interactions | .07*** | .31*** | .56*** | ||

| Δ Damage My Braina × Groupb | 2.90 | -.13 | |||

| Δ Lose My Friends’ Respecta × Groupb | 0.02 | .01 | |||

| Δ Have a Good Time With My Friends × Groupb | 8.35 | .13** | |||

| Δ Be More Creative and Imaginative × Groupb | 1.39 | -.06 | |||

| Δ Be Acting Against My Moral Beliefsa × Groupb | 8.29 | .15** | |||

| Δ Mess Up My Lifea × Groupb | 3.64 | .14 | |||

| Δ Do Worse in Schoola × Groupb | 4.35 | .13* | |||

| Δ Lose My Ambitiona × Groupb | 0.12 | -.03 | |||

Note. Reference group for race is Caucasian.

Reversed so that positive change score represents a shift to perceiving marijuana as less harmful.

1 = nonusers at Year 1 who remained nonusers at Year 2; 2 = nonusers at Year 1 who became users at Year 2.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Step 1: Demographics

The demographic covariates as a block were statistically significant, but no single indicator was significantly predictive in the final model. This step explained only 1% of the variance in change in intentions.

Step 2: Main effects of the expectancy variables

At Step 2, which included all eight of the EC measures, the model was statistically significant and explained 10% of the variance in intentions (p < .001). Two expectancy effects were statistically significant predictors of intentions to use marijuana across all respondents, regardless of user status. After adjusting for all other effects in the model, a positive EC of “Mess up my life” (β= .14, p < .01) was significantly related with increased change in intention to use marijuana. A positive EC to “Do worse in school” (β= .10, p < .05) also was significantly related with an increase in marijuana intentions from one year to the next.

Step 3: Main effect of the grouping variable

When adjusting for all other effects, the grouping variable (nonusers at Year 1 who remained nonusers at Year 2 vs. nonusers at Year 1 who became users at Year 2) was significantly related to change in marijuana intentions (β= .28, p < .001).

Step 4: Interaction effects

After controlling for variables in the previous steps, the interaction block explained an additional 7% of the variance in the model. Several statistically significant EC × Grouping Status interaction effects emerged. These interactions indicated that user status statistically moderated the relationship of expectancy on intentions, thus supporting Hypothesis 2.

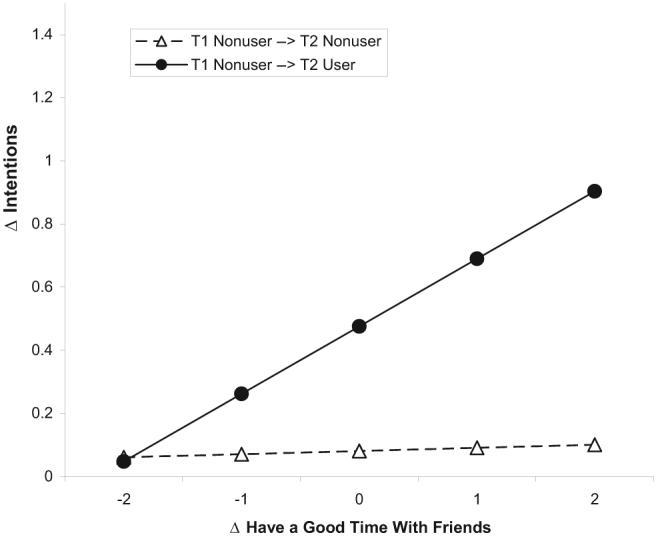

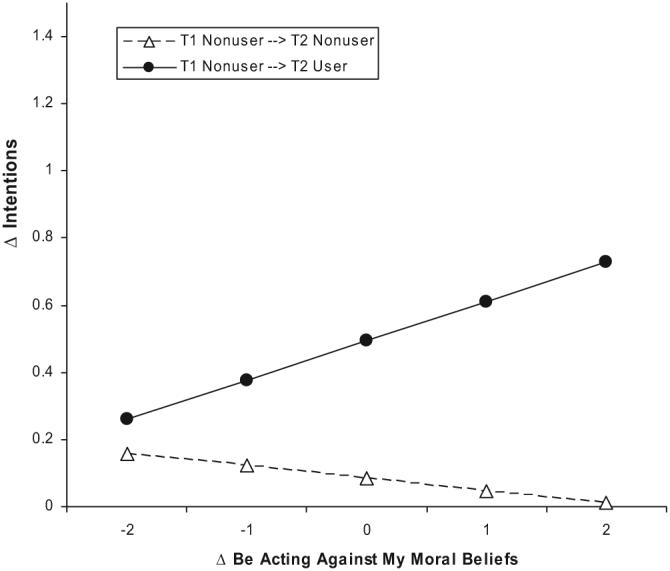

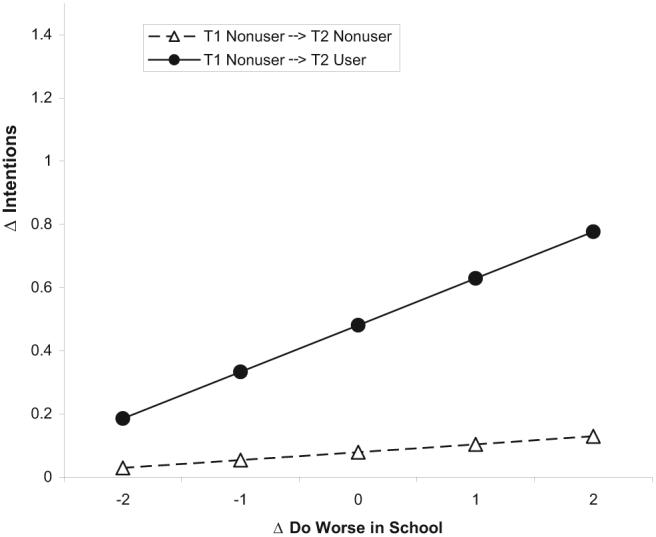

To probe each statistically significant interaction, simple slopes were estimated and graphed (Aiken & West, 1991). In each of these plots, which have controlled for all other effects in the regression model, the two slopes represent respondents’ Year 2 user status, the moderator variable. For interpretability, the x- and y-axes correspond to raw change scores. On the abscissa, a score value of zero (0) represents no change of expectancies; negative values (-1 or -2) represent negative changes (shift to perceiving marijuana as more harmful); and positive values (1 or 2) represent positive changes (shift to perceiving marijuana as less harmful). The predicted values are represented on the ordinate.

An interaction effect of Have a Good Time With My Friends × Group Status (β= .13, p < .01) emerged in the analysis (Figure 1), as did a statistically significant interaction of Be Acting Against My Moral Beliefs × Group Status (β= .15, p < .01; Figure 2), and of Do Worse in School × Group Status (β= .13, p < .05; Figure 3). In support of Hypothesis 2, these moderation effects indicate that when certain marijuana expectancies are violated as a result of use, intentions to use marijuana proportionately increase. When expectancies change as a result of indirect experience, there is little impact on future marijuana intentions, as illustrated.

Figure 1.

Group status moderating the effect of the expectancy item “Have a good time with my friends” on marijuana intentions. T1 = Year 1; T2 = Year 2.

Figure 2.

Group status moderating the effect of the expectancy item “Be acting against my moral beliefs” on marijuana intentions. T1 = Year 1; T2 = Year 2.

Figure 3.

Group status moderating the effect of the expectancy item “Do worse in school” on marijuana intentions. T1 = Year 1; T2 = Year 2.

Discussion

Results supported both hypotheses. The first analysis revealed positive correlations between changes in expectancies and changes in intentions. More importantly, in most cases changes in expectancies observed among users were more strongly related to future intentions than were those found among nonusers. A plausible interpretation of this result that bears further examination is that ECs brought about by actual experience have greater effects on subsequent intentions than do ECs that occur as a result of less direct causes.

Consistent with laboratory studies, changes in marijuana expectancies were predictive of changes in marijuana usage intentions. For each of the eight expectancies, changes in expectations favorable to marijuana were associated significantly with positive changes in marijuana intentions. As suggested in the moderation analyses, expectancies involving having a good time with friends, school, and moral beliefs may be particularly sensitive to changes in expectations. The quasi-experimental nature of this design precludes a strong causal claim that changes in the expectancies of users came about as a result of usage. However, though the correlational results cannot rule out rival alternative explanations, the findings are consistent with predictions based on the expectancy violation framework. As shown, in every case the correlation between the changed expectancy and the corresponding change in intention was greater in the Year 2 user group (vs. the Year 2 nonuser group); in four of the eight comparisons, the differences in correlations were statistically significant.

The results of the hierarchical regression analysis disclosed a set of intriguing and statistically significant interactions. Rival alternative explanations of quasi-experimental results generally prove difficult to generate when considering interaction effects (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). In the analysis, the interaction of ECs and group status predicted changes of intentions. Investigation of the interactions summarized in Figures 1 to 3 disclosed stronger relationships between changes in expectancies and changes in usage intentions for adolescents who had tried marijuana between the 1st and 2nd years’ surveys, as opposed to those of adolescents who had remained abstinent. ECs were more predictive of changes in intentions among users than nonusers. Future studies, particularly ones with more frequent data collection points, would do well to replicate the current results and explore the possibility that varying degrees of experience and engagement moderate the relationship between ECs and later behavior. In addition, research should address the causal priority of processes linking expectancies and intentions. There are many possible influences on EC (e.g., peer use and influence) that were not examined in this study. Some adolescents, for example (those with conduct problems), may be more likely to show changes in expectancies with age and marijuana use. Attention should be focused on whether users attained user status prior to a change in expectancies or rather if a change in expectancies resulted in changes to user status.

A potential limitation of the study is that single item measures of expectancies were used. It was necessary to do so to examine in detail the specific expectancy items associated with changes in intentions. Much of this information would have been lost if these items had been combined in a composite. The significant expectancies found in our nationally representative study should be investigated in future research.

Implications and Applications

The results of this research have novel and potentially important implications for health promotion, education, and intervention. It may seem reasonable in prevention efforts to stress the physical and psychological harms of using drugs, but this approach requires caution. Our results suggest that if adolescents choose to initiate marijuana use, the likelihood of continuance may be affected by the extent to which their expectancies have been violated. If adolescents find that the promised harms are not nearly as severe as they had been led to expect on the basis of well-intentioned prevention strategies, their ECs may strengthen usage intentions. This possibility calls for a serious reconsideration of the costs of prevention campaign failures. Commonly, when a campaign message promising dire consequences fails, its costs are calculated in terms of lost opportunities, campaign outlays, and so on. The results of our analyses suggest a more profound cost. When threatened outcomes are experienced as less severe than anticipated, intentions to engage in threatened behaviors may be amplified.

Convincing adolescents that marijuana use produces extreme social, cognitive, and academic harm might seem a reasonable method of primary prevention, but this approach may render secondary and tertiary prevention efforts more difficult. That our data were derived from an evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign should not be taken as an implicit or explicit evaluation of the ads used in this campaign. The results of our analyses do not identify the sources of respondents’ expectations. Our results do indicate that the best chance for reducing future use might be to persuade adolescents that if they do initiate use, the harms they will experience at some point may prove worse than anticipated, or the expected benefits may not prove as positive. At a minimum, the results warn against overstating marijuana harms in prevention.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant 5R01DA020879-02.

Footnotes

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Atkin C. Promising strategies for media health campaigns. In: Crano WD, Burgoon M, editors. Mass media and drug prevention: Classic and contemporary theories and research. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer CB, Tschann JM, Shafer M. Predictors of risk for sexually transmitted diseases in ninth grade urban high school students. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:448–465. doi: 10.1177/0743558499144004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys A, Marsden J, Griffiths P, Fountain J, Stillwell G, Strang J. Substance use among young people: The relationship between perceived functions and intentions. Addiction. 1999;94:1043–1050. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94710439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen BA, Smith GT, Roehling PV, Goldman MS. Using alcohol expectancies to predict adolescent drinking behavior one year after. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:93–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig KD. Physiological arousal as a function of imagined, vicarious, and direct stress experiences. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1968;73:513–520. doi: 10.1037/h0026531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig K, Wood K. Physiological differentiation of direct and vicarious affective arousal. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science. 1969;2:98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 2nd ed. Sage; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Solowij N. Adverse effects of cannabis. The Lancet. 1998 November 14;352:1611–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R. Public health communication: Making sense of the evidence. In: Hornik R, editor. Public health communication. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R. Personal influence and the effects of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2006;608:282–300. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2006. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: May, 2007. NIH Publication No. 07-6202. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, Corbin W, Fromme K. A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2001;96:57–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernahan C, Bartholow BD, Bettencourt BA. Effects of category-based expectancy violation on affect-related evaluations: Toward a comprehensive model. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2000;22:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist T. Cognitive consequences of cannabis use: Comparison with abuse of stimulants and heroin with regard to attention, memory and executive functions. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2005;81:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey M, Hall W. The effects of adolescent cannabis use on educational attainment: A review. Addiction. 2000;95:1621–1630. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse . ‘User’s guide for the evaluation of the national youth anti-drug media campaign: Restricted use files for the National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY), Rounds 1, 2, 3, and 4. Westat; Rockville, Maryland: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Orwin R, Cadell D, Chu A, Kalton G, Maklan D, Morin C, et al. Evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign: 2004 Report of Findings, Executive Summary. Westat; Washington DC: 2006. Report prepared for the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Contract No. N01DA-8-5063) [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa DR, Willett JB. Demonstrating the reliability of the difference score in the measurement of change. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1983;20:335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Brown SA. Marijuana and cocaine effect expectancies and drug use patterns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:558–565. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin; Boston, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Jr., Friedman GD, Tekawa IS. Marijuana use and cancer incidence (California, United States) Cancer Causes and Control. 1997;8:722–728. doi: 10.1023/a:1018427320658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley A. Marijuana: On road and driving simulator studies. In: Kalant H, Corrigall W, Hall W, Smart R, editors. The health effects of cannabis. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto, Ontario, Canada: 1999. pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Stacy A. Memory association and ambiguous cues in models of alcohol and marijuana use. Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 1995;3:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. 2005a. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-25, DHHS Publication No. SMA 05-4062. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Office of Applied Studies. National survey on drug use and health. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2005b. ICPSR04596-v1. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Westat . WesVar 4.0, ‘user’s guide. Author; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman DW, Williams RH. Gain scores in research can be highly reliable. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1982;19:149–154. [Google Scholar]