Abstract

OBJECTIVE—Polymorphisms in the adiponectin gene (ADIPOQ) have been associated with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes, in mostly European-derived populations.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—A comprehensive association analysis of 24 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the adiponectin gene was performed for type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in African Americans.

RESULTS—The minor allele (A) in a single SNP in intron 1 (rs182052) was associated with diabetic nephropathy (P = 0.0015, odds ratio [OR] 1.37, CI 1.13–1.67, dominant model) in an African American sample of 851 case subjects with diabetic nephropathy and 871 nondiabetic control subjects in analyses incorporating adjustment for varying levels of racial admixture. This association remained significant after adjustment of the data for BMI, age, and sex (P = 0.0013–0.0004). We further tested this SNP for association with longstanding type 2 diabetes without nephropathy (n = 317), and evidence of association was also significant (P = 0.0054, OR 1.46, CI 1.12–1.91, dominant model) when compared with the same set of 871 nondiabetic control subjects. Combining the type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy samples into a single group of case subjects (n = 1,168) resulted in the most significant evidence of association (P = 0.0003, OR 1.40, CI 1.17–1.67, dominant model). Association tests between age at onset of type 2 diabetes and the rs182052 genotypes also revealed significant association between the presence of the minor allele (A/A or A/G) and earlier onset of type 2 diabetes.

CONCLUSIONS—The SNP rs182052 in intron 1 of the adiponectin gene is associated with type 2 diabetes in African Americans.

Type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy are more prevalent among African Americans than European Americans, even when taking into consideration ethnic differences in socioeconomic status, prevalence and severity of hypertension, and access to adequate health care (1–3). Studies of African American families with type 2 diabetes (4) or diabetic nephropathy (5) have revealed clustering of both diseases, indicating a genetic component to susceptibility. Genome scans in families have supported a genetic contribution to susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in African Americans (4,6).

Plasma adiponectin levels are inversely correlated with diabetes and insulin resistance (7,8). In contrast, plasma adiponectin has been shown to be increased in patients with kidney disease (9), and studies suggest that increased adiponectin concentration is a predictor of subsequent kidney disease (10).

Adiponectin gene (ADIPOQ) polymorphisms have been implicated in type 2 diabetes (11) and type 1 diabetic nephropathy (12,13). Few studies have addressed genetic variants in adiponectin and association with diabetes in Africans (14) or African Americans (15). This second report in African Americans noted several differences between European-derived samples and African Americans regarding associations between ADIPOQ polymorphisms and body composition and lipid phenotypes highlighting potential ethnic differences in the adiponectin gene and the importance of investigating variants in this gene in African Americans.

Given the paucity of studies on adiponectin gene polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes or diabetic nephropathy in African Americans and the high risk of these diseases in this population, a thorough interrogation of this gene in African Americans was warranted. We tested 24 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the adiponectin gene for association with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in a large collection of African Americans residing in the southeastern U.S.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Case subjects included 851 unrelated African Americans with type 2 diabetes–associated end-stage renal disease (ESRD) from dialysis centers in Winston-Salem, Greensboro, and Hickory, NC. All diabetic nephropathy case subjects had ESRD and were on dialysis at the time of recruitment. Diabetes was considered to be the primary cause of nephropathy if subjects developed diabetes after the age of 35 years and diabetes was present >5 years before initiation of renal replacement therapy and/or in the presence of diabetic retinopathy or proteinuria exceeding 500 mg/24 h. An additional 317 unrelated African Americans with type 2 diabetes and no renal disease, and 871 nondiabetic unrelated control subjects were recruited from medical clinics, churches, and health fairs in North Carolina. Diabetic subjects lacking nephropathy had diabetes for >10 years with a spot urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio <30 mg/g and serum creatinine concentration <1.5 mg/dl in men or <1.3 mg/dl in women. Individuals were actively receiving treatment with oral hypoglycemic agents and/or insulin. Nondiabetic control subjects were self-reported African Americans born in the southeast, age ≥18 years, who denied a personal history of diabetes or a personal or family history of kidney disease in first-degree relatives. Each participant provided 40 ml blood for DNA isolation. DNA was isolated using an AutoPure LS automated DNA extraction robot (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Recruitment and sample collection procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest University, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

SNP genotyping.

A total of 24 SNPs were genotyped in 1,168 African American case subjects (851 with diabetic nephropathy and 317 with type 2 diabetes lacking nephropathy) and 871 nondiabetic control subjects. SNPs were chosen based on their ability to capture genetic information for African (Yoruban) and European (CEU) populations in Hapmap (www.hapmap.org) using Tagger (Haploview [16]). Tagged SNPs had a minor allele frequency >0.05 and captured an inter-SNP r2 value >0.8 for known polymorphisms in the region. Three SNPs, rs17300539, rs4632532, and rs266729, were included based on previous association with type 1 diabetic nephropathy or insulin resistance syndrome phenotypes (13,17). A total of 34 SNPs were initially chosen for analysis. Two SNPs failed design, six SNPs could not be incorporated into a multiplex, and two SNPs were eliminated because of low genotyping efficiency. The genotyped SNPs captured at least 64% of the variation in the Yoruban HAPMAP sample. SNPs were genotyped using the MassARRAY genotyping system (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). PCR primers were designed using the MassARRAY Assay Design 3.4 Software (Sequenom). All case and control subjects were genotyped at 70 admixture informative markers (AIMs) to estimate the percentage of African ancestry for each individual (18,19).

DNA sequencing.

The associated SNP rs182052 was sequenced in 175 African Americans with diabetic nephropathy to verify the accuracy of the genotype calls. The region was PCR amplified and products were purified and directly sequenced using Big Dye Ready Reaction Mix on an ABI3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence data were visualized using Sequencher Software version 4.6 (GeneCodes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI).

Statistical analysis.

Biometric data were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks (SigmaStat; Systat Software, San Jose, CA) with a Dunn's method multiple comparison test. Age at onset of type 2 diabetes in the diabetic nephropathy and type 2 diabetic case subjects was compared using a Mann-Whitney rank-sum test (SigmaStat). Each SNP was tested for departures from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium using the χ2 goodness-of-fit test in the statistical analysis program SNPGWA (www.phs.wfubmc.edu) (20). Tests for genotypic association were performed on each SNP individually using SNPGWA-ADMIX, a component of the SNPGWA program that includes the capability to perform association calculations adjusting for covariates. Genotypic association reported here is for analyses incorporating adjustment for ancestry proportions. The primary inference is based on the 2 d.f. global test of genotypic association. If significant, then the individual genetic models (dominant, additive, and recessive) were examined for context. This is consistent with the Fisher's protected least significant difference multiple comparisons procedure. Percentage of African ancestry was computed from 70 admixture informative markers using the program Frappe (18,19). The influence of other possible covariates (age, BMI, and sex) on evidence of association was tested using SNPGWA-ADMIX. Two-SNP haplotype analysis was completed using the program Dandelion (www.phs.wfubmc.edu). Linkage disequilibrium was calculated as defined by Gabriel et al. (21) with the program Haploview (16).

We computed a series of Cox proportional hazards models and the corresponding likelihood ratio statistics to test for associations between adiponectin polymorphisms and age at type 2 diabetes onset for 1) diabetic nephropathy case subjects, 2) type 2 diabetic (no nephropathy) case subjects, and 3) type 2 diabetic and diabetic nephropathy case subjects combined. Here, age at type 2 diabetes onset was computed for the above three conditions and was contrasted with the age of nondiabetic control subjects at time of enrollment; specifically, control subjects had “age at onset of type 2 diabetes” censored at age of enrollment. The hazards ratio (HR) and corresponding 95% CI was computed as exp(β̂) and exp [β̂ ± 1.96 × SE (β̂)], respectively. Tests for association and the estimates for the hazards ratio were computed without covariate adjustment and adjusting for sex, BMI, and admixture estimates. As discussed above, the genetic models are defined relative to the minor allele frequency.

RESULTS

Descriptive data for participants are summarized in Table 1. Diabetic nephropathy and type 2 diabetic case subjects were older and more were female compared with the nondiabetic control subjects. Type 2 diabetic case subjects had increased BMI compared with diabetic nephropathy case subjects and nondiabetic control subjects. The average age at type 2 diabetes onset for case subjects with diabetic nephropathy was less than that of case subjects with type 2 diabetes without nephropathy.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of African American cohort

| n | Age | BMI | % female | Age at onset of type 2 diabetes | Age at onset of ESRD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nondiabetic control subjects | 871 | 50.9 ± 11.6 | 29.5 ± 7.0 | 55.1 | ||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 851 | 61.8 ± 10.0* | 29.4 ± 6.8 | 62.7 | 41.0 ± 12.0 | 58.5 ± 10.2 |

| Type 2 diabetes (no nephropathy) | 317 | 58.6 ± 11.5* | 32.9 ± 7.1* | 65.5 | 43.8 ± 12.0† |

Mean is significantly different from nondiabetic subjects (P < 0.05).

Mean is significantly different (P < 0.05) from the type 2 diabetes (no nephropathy) case subjects.

A total of 24 SNPs in the adiponectin gene were successfully genotyped in diabetic nephropathy case subjects and nondiabetic control subjects. None of the SNPs departed from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium after correction for multiple comparisons. Two SNPs, rs182052 and rs3821799, showed evidence of association with diabetic nephropathy (Supplemental Table 1, found in an online appendix at http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db08-0598). SNP rs182052 was associated with diabetic nephropathy in the 2 d.f. test (P = 0.002) and under the dominant model (P = 0.002, odds ratio [OR] 1.37; 95% CI 1.13–1.67) (Table 2). SNP genotype calls for rs182052 were verified by direct DNA sequence analysis in 175 case subjects with diabetic nephropathy to ensure that the slight departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the case subjects was not the result of erroneous genotyping. Genotypes observed from DNA sequencing were 100% concordant with genotypes generated from the Sequenom MassArray system. The SNP rs3821799 was also associated (P = 0.039) but did not retain statistical significance after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

TABLE 2.

Genotypic association with diabetic nephropathy and type 2 diabetes

| Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

|

Genotypic association

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 d.f. | Dominant

|

Additive

|

Recessive

|

|||||||||

| Case subjects | Control subjects | P | P | OR | CI | P | OR | CI | P | OR | CI | |

| Diabetic nephropathy vs. nondiabetic | ||||||||||||

| Admixture | 0.024 | 0.060 | 0.0019 | 0.0015 | 1.37 | 1.13–1.67 | 0.0393 | 1.16 | 1.01–1.34 | 0.6442 | 0.94 | 0.71–1.24 |

| Age | 0.0032 | 0.0009 | 1.49 | 1.18–1.89 | 0.0081 | 1.26 | 1.06–1.49 | 0.6225 | 1.09 | 0.78–1.53 | ||

| BMI | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | 1.46 | 1.19–1.80 | 0.0110 | 1.22 | 1.05–1.42 | 0.9334 | 0.99 | 0.73–1.34 | ||

| Sex | 0.0017 | 0.0013 | 1.38 | 1.13–1.67 | 0.0378 | 1.16 | 1.01–1.34 | 0.6330 | 0.93 | 0.70–1.24 | ||

| Combined | 0.0019 | 1.46 | 1.15–1.86 | 0.0114 | 1.25 | 1.05–1.49 | 0.5593 | 1.11 | 0.79–1.56 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes + diabetic nephropathy vs. nondiabetic | ||||||||||||

| Admixture | 0.003 | 0.061 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 1.40 | 1.17–1.67 | 0.0196 | 1.17 | 1.03–1.33 | 0.5549 | 0.92 | 0.71–1.20 |

| Age | 0.0006 | 0.0002 | 1.50 | 1.21–1.86 | 0.0058 | 1.25 | 1.07–1.46 | 0.8796 | 1.02 | 0.75–1.40 | ||

| BMI | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 1.47 | 1.21–1.79 | 0.0075 | 1.22 | 1.05–1.41 | 0.7473 | 0.95 | 0.72–1.27 | ||

| Sex | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 1.41 | 1.17–1.69 | 0.0187 | 1.17 | 1.03–1.34 | 0.5110 | 0.92 | 0.70–1.19 | ||

| Combined | 0.0005 | 1.48 | 1.19–1.84 | 0.0088 | 1.24 | 1.06–1.45 | 0.8408 | 1.03 | 0.75–1.42 | |||

Genotypic association for rs182052 after individual adjustment for admixture, age, BMI, and sex in 851 type 2 diabetes + diabetic nephropathy case subjects versus 871 nondiabetic control subjects and type 2 diabetes + diabetic nephropathy case subjects plus an additional 317 type 2 diabetic (no nephropathy) subjects (total cases = 1,168) versus the same 871 nondiabetic control subjects. Genotypic association is also shown for all four covariates simultaneously (combined).

SNP rs182052 was associated with BMI and waist measures in Hispanic Americans in the Insulin Resistance and Atherosclerosis (IRAS) Family Study (22). To ascertain whether the association of rs182052 with diabetic nephropathy reflected an association with BMI or other phenotypes known to be associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes or diabetic nephropathy, genotypic association was evaluated with individual adjustments for BMI, sex, and age at exam (Table 2) and showed little effect on the evidence of association. We also tested association after simultaneously adjusting for admixture, BMI, sex, and age. Evidence of association between rs182052 and diabetic nephropathy remained significant (P = 0.0019, OR 1.46, CI 1.15–1.86) under the dominant model.

To discern whether rs182052 was associated with nephropathy or diabetes in our African American sample, this SNP was tested for association in 317 African Americans with longstanding type 2 diabetes without nephropathy versus the 871 nondiabetic control subjects. This SNP was associated with type 2 diabetes under the dominant model (P = 0.0054; OR 1.46, CI 1.12–1.91) after adjustment for African ancestry proportions, and the association remained significant with adjustment for all four covariates (P = 0.0056, OR 1.54, CI 1.13–2.09) (Supplemental Table 2). When evaluating all 1,168 African American diabetic individuals (851 with diabetic nephropathy and 317 with type 2 diabetes without nephropathy), rs182052 remained associated with type 2 diabetes under the dominant model (P = 0.0003, OR 1.40, CI 1.17–1.67) with adjustment for proportion of African ancestry (Table 2). Individual and combined adjustment for African ancestry, age, BMI, and sex did not significantly alter this result. To clarify whether the association was with type 2 diabetes only or also with nephropathy, we tested rs182052 for association between the two groups of case individuals: diabetic nephropathy and type 2 diabetes lacking nephropathy. There was no association detected (P = 0.87, OR 0.98, CI 0.73–1.30), indicating that the rs182052 is associated with type 2 diabetes status and not nephropathy.

The linkage disequilibrium structure for the adiponectin gene in African American nondiabetic control subjects is shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. African Americans have one large block at the 3′ end of the gene and four smaller blocks surrounding it. The associated SNP, rs182052, is located in a small linkage disequilibrium block containing one other known SNP, rs266729, and covering the promoter.

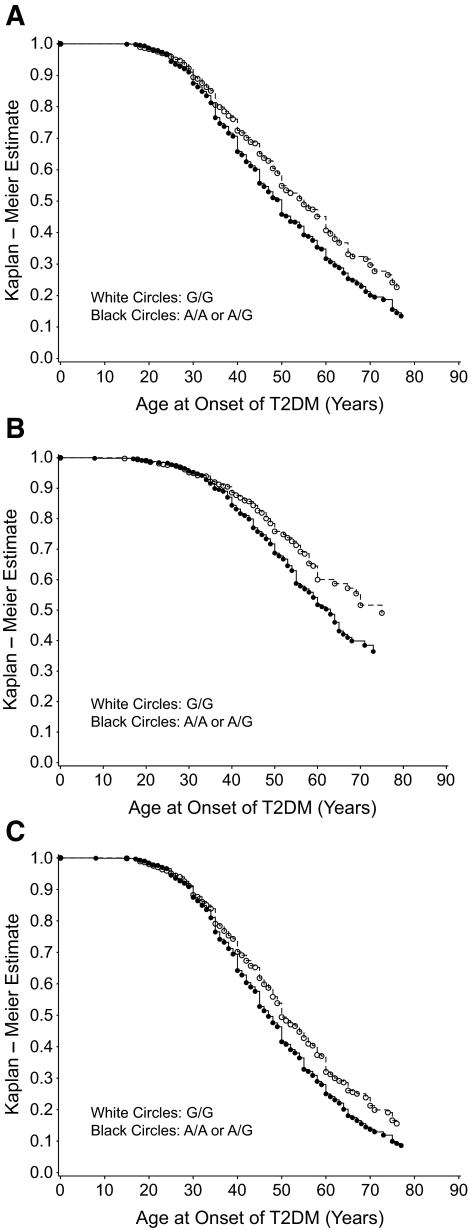

FIG. 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots for age of onset of type 2 diabetes by genotype for diabetic nephropathy case subjects (n = 851) and control subjects (n = 871) (A), type 2 diabetic case subjects (n = 317) and control subjects (B), and diabetic nephropathy + type 2 diabetic case subjects (n = 1,168) and control subjects (C). T2DM, type 2 diabetes.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the relative risk (RR) for early age at onset of type 2 diabetes for genotypes at the associated SNP, rs182052 (Table 3). Significant risk for earlier onset of type 2 diabetes was detected under the dominant model (P = 0.0031–0.0002; RR 1.26–1.41) for the diabetic nephropathy and type 2 diabetic case groups individually and when the two groups were combined (diabetic nephropathy + type 2 diabetes). Significant risk was also found with age at onset of ESRD under the dominant model (P = 0.0113; RR 1.20). RR increased when the data were adjusted for sex, BMI, and admixture (P = 0.0084; RR 1.21). Pearson's correlation coefficient (r = 0.56; P < 0.001) indicated a positive correlation between the age at onset of type 2 diabetes and the age at onset of ESRD, suggesting that early age of onset of ESRD may depend on an early age of onset of type 2 diabetes. We confirmed this by calculating the RR of age at onset of ESRD after adjustment for age at onset of type 2 diabetes and saw no significant risk (Table 3). When the survival distribution function is plotted versus the age at onset of type 2 diabetes (Fig. 1), individuals with the minor allele A (A/A or A/G genotypes) have an earlier age at onset of type 2 diabetes compared with individuals who are homozygous for the G allele (G/G genotype).

TABLE 3.

Survival analysis to estimate risk of early age at onset of type 2 diabetes and ESRD

| Dominant

|

Recessive

|

Additive

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | RR | P | RR | P | RR | |

| Age at onset of type 2 diabetes | ||||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 0.0003 | 1.29 | 1.0000 | 1.00 | 0.0102 | 1.14 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 0.0031 | 1.41 | 0.9714 | 0.99 | 0.0338 | 1.19 |

| Diabetic nephropathy + type 2 diabetes | 0.0002 | 1.26 | 0.9217 | 1.01 | 0.0063 | 1.13 |

| After adjustment | ||||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 0.0011 | 1.27 | 0.9391 | 0.99 | 0.0192 | 1.13 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 0.0034 | 1.42 | 0.7143 | 0.94 | 0.0507 | 1.17 |

| Diabetic nephropathy + type 2 diabetes | 0.0004 | 1.25 | 0.9878 | 1.00 | 0.0091 | 1.12 |

| Age at onset of ESRD | ||||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 0.0113 | 1.20 | 0.1443 | 1.17 | 0.0098 | 1.14 |

| After adjustment for sex, BMI, and admixture | ||||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 0.0084 | 1.21 | 0.1148 | 1.18 | 0.0063 | 1.16 |

| After adjustment for age at onset of type 2 diabetes | ||||||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.34 | 1.11 | 0.73 | 1.03 |

P values and RRs are reported for the dominant, additive, and recessive models both before and after adjustment for sex, BMI, and admixture proportions. Analysis of age at onset of ESRD is also adjusted for age at onset of type 2 diabetes.

DISCUSSION

We have evaluated association between adiponectin gene polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in a large sample of African Americans. We observed evidence of association between the rs182052 polymorphism in intron 1 in African Americans with type 2 diabetes. This evidence of association remained significant after adjustment for African ancestry, age, BMI, and sex. In the fully adjusted models, the P value for association of rs182052 with type 2 diabetes was 0.0005, a level of significance that survives even stringent Bonferroni adjustment. Survival analysis revealed association between the minor allele and earlier age at onset of type 2 diabetes. Previous studies of association between adiponectin polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes or diabetic nephropathy have evaluated European-derived or Asian populations, with only one study in non-European South Africans (14) and one study with a small number of African Americans (15). To our knowledge, this is the first study that has addressed adiponectin gene polymorphism associations with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy in African Americans.

In our case samples, allele frequencies of rs182052 deviated slightly from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. This may be the result of differing allele frequencies in the European and African ancestral populations. In HapMap (www.hapmap.org), the Yoruban population has a minor allele frequency of 0.395 at this SNP, whereas the European population has a minor allele frequency of 0.353. This difference underscores the importance of including adjustment for African Ancestry in analyses of African American populations. In our case subjects and control subjects, the percentage of African ancestry was similar between the two groups of case subjects and the control subjects (80 ± 10 to 82 ± 10).

This study was well powered to detect associations consistent with complex genetic traits with over 1,168 (combined) type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy case subjects and more than 871 nondiabetic control subjects. With this large sample size, we had >80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.3–1.5 under the dominant model of association within a range of minor allele frequencies (0.1–0.3). While a number of the genotyped SNPs had low minor allele frequencies (<0.05) and would contribute to a reduction in power, the associated SNP was relatively common (minor allele frequency = 0.348 in control subjects) and the low P value contributes a high level of confidence in this association.

Previous studies have reported association between adiponectin polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes (14,15,23–26) and diabetic nephropathy (13). These studies have primarily detected association with SNPs in the promoter region (rs17300539 and rs266729) or in exons (rs22517766 and rs1501299). With our African American sample, we have the ability to detect association with both type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. We tested three of these SNPs (rs17300539, rs266729, and rs1501299) and found no significant evidence for association. That the association in our African American collection is at a different SNP is not unexpected. This may reflect ethnic differences in adiponectin gene structure, as discussed by Ukkola et al. (15) in their evaluation of African Americans from the HERITAGE study. The lack of two distinct linkage disequilibrium blocks in the adiponectin gene in our African American sample, compared with that previously demonstrated in European-derived samples (27), also supports this conclusion. In addition, Woo et al. (28) identified nine SNPs in the adiponectin gene that had significantly different minor allele frequencies (P < 0.001) between African Americans and European Americans. These genetic data are further supported by evidence that African Americans have reduced plasma adiponectin concentrations than other ethnic groups (Europeans, Japanese, and Pima Indians) (29). The potential for ethnic differences in the adiponectin gene emphasizes the need to study genetic associations in multiple populations, particularly African Americans.

Whereas association with type 2 diabetes has not been previously reported with rs182052, this SNP has been associated with BMI and waist measures in Hispanic Americans in the Insulin Resistance and Atherosclerosis Family Study (22). To ascertain whether the association we observed was the result of type 2 diabetes and not increased BMI, we adjusted for BMI in the association analysis. The evidence of association remained significant after BMI adjustment, indicating that the difference in adiposity between case subjects and control subjects is not driving the association and that the mechanism is via some other pathway. In addition, rs182052 is in the same haplotype block as rs266729 (Supplementary Fig. 1) in African Americans, an SNP with prior reports of association with type 2 diabetes (11). Haplotype analysis of these two SNPs revealed no association with type 2 diabetes or diabetic nephropathy (Supplementary Table 3).

Woo et al. (28) and Heid et al. (27) have demonstrated association between the minor allele of rs182052 (A) and reduced levels of plasma adiponectin in European-derived American adolescents and healthy Europeans, respectively. In our study, individuals with the minor allele (A/A or A/G genotypes) had earlier onset of type 2 diabetes. If the minor allele is contributing to type 2 diabetes in our samples by reduced levels of plasma adiponectin, this would be consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated an association between hypoadiponectinemia and increased risk of type 2 diabetes (24,30). We do not have serum adiponectin concentrations for the subjects in our study; however, it would be interesting to determine whether rs182052 contributes to plasma adiponectin concentrations in our collection of African Americans. It should be noted that Woo et al. (28) detected no association between rs182052 and plasma adiponectin levels in a comparably sized sample of African American adolescents.

A primary issue with the observations we have made is whether the observed association reflects an association between rs182052 and type 2 diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, or both. We have sampled a relatively large number of African American subjects with diabetic nephropathy and a smaller collection with type 2 diabetes and no nephropathy to attempt to ascertain whether this gene is associated with nephropathy or diabetes. As the SNP was associated in subjects with diabetic nephropathy and subjects with type 2 diabetes lacking nephropathy, we believe that the data are most consistent with the rs182052 variant contributing to type 2 diabetes susceptibility in African Americans. This is supported by the Cox model's RR, which indicated increased risk for earlier age at onset of type 2 diabetes. Additionally, we compared allele frequencies of rs182052 between the diabetic nephropathy case subjects (n = 851) and the type 2 diabetic (no nephropathy) case subjects (n = 317) and observed no evidence of association. Although this analysis has less power than the initial case-control analysis, it does support our conclusion that rs182052 is associated with type 2 diabetes in African Americans.

We observed association between a variant in the adiponectin gene and type 2 diabetes in African Americans. This SNP, rs182052, has not previously been associated with diabetes or diabetic nephropathy in other populations, although it has been associated with plasma adiponectin levels. That other variants previously associated with diabetes or diabetic nephropathy in Europeans were not associated in our African American population emphasizes the potential that there are likely ethnic differences in the linkage disequilibrium structure of the adiponectin gene.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the General Clinical Research Center of the Wake Forest University School of Medicine grants M01 RR07122, R01 DK066358 (D.W.B.), R01 DK053591 (D.W.B.), and R01 DK 070941 (B.I.F.). M.A.B. was supported by grant F32 DK080617 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Published ahead of print at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org on 3 December 2008.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whittle JC, Whelton PK, Seidler AJ, Klag MJ: Does racial variation in risk factors explain black-white differences in the incidence of hypertensive end-stage renal disease? Arch Intern Med 151: 1359–1364, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne C, Nedelman J, Luke RG: Race, socioeconomic status, and the development of end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 23: 16–22, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brancati FL, Kao WH, Folsom AR, Watson RL, Szklo M: Incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American and white adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA 283: 2253–2259, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sale MM, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Williams AH, Hicks PJ, Colicigno CJ, Beck SR, Brown WM, Rich SS, Bowden DW: A genome-wide scan for type 2 diabetes in African-American families reveals evidence for a locus on chromosome 6q. Diabetes 53: 830–837, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman BI, Tuttle AB, Spray BJ: Familial predisposition to nephropathy in African-Americans with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Kidney Dis 25: 710–713, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowden DW, Colicigno CJ, Langefeld CD, Sale MM, Williams A, Anderson PJ, Rich SS, Freedman BI: A genome scan for diabetic nephropathy in African Americans. Kidney Int 66: 1517–1526, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y, Takahashi M, Matsuda M, Okamoto Y, Iwahashi H, Kuriyama H, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Nishida M, Kihara S, Sakai N, Nakajima T, Hasegawa K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Hanafusa T, Matsuzawa Y: Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1595–1599, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, Tataranni PA: Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 1930–1935, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenvinkel P, Marchlewska A, Pecoits-Filho R, Heimburger O, Zhang Z, Hoff C, Holmes C, Axelsson J, Arvidsson S, Schalling M, Barany P, Lindholm B, Nordfors L: Adiponectin in renal disease: relationship to phenotype and genetic variation in the gene encoding adiponectin. Kidney Int 65: 274–281, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollerits B, Fliser D, Heid IM, Ritz E, Kronenberg F: Gender-specific association of adiponectin as a predictor of progression of chronic kidney disease: the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease Study. Kidney Int 71: 1279–1286, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menzaghi C, Trischitta V, Doria A: Genetic influences of adiponectin on insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes 56: 1198–1209, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma J, Mollsten A, Falhammar H, Brismar K, Dahlquist G, Efendic S, Gu HF: Genetic association analysis of the adiponectin polymorphisms in type 1 diabetes with and without diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications 21: 28–33, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vionnet N, Tregouet D, Kazeem G, Gut I, Groop PH, Tarnow L, Parving HH, Hadjadj S, Forsblom C, Farrall M, Gauguier D, Cox R, Matsuda F, Heath S, Thevard A, Rousseau R, Cambien F, Marre M, Lathrop M: Analysis of 14 candidate genes for diabetic nephropathy on chromosome 3q in European populations: strongest evidence for association with a variant in the promoter region of the adiponectin gene. Diabetes 55: 3166–3174, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olckers A, Towers GW, van der Merwe A, Schwarz PE, Rheeder P, Schutte AE: Protective effect against type 2 diabetes mellitus identified within the ACDC gene in a black South African diabetic cohort. Metabolism 56: 587–592, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ukkola O, Santaniemi M, Rankinen T, Leon AS, Skinner JS, Wilmore JH, Rao DC, Bergman R, Kesaniemi YA, Bouchard C: Adiponectin polymorphisms, adiposity and insulin metabolism: HERITAGE family study and Oulu diabetic study. Ann Med 37: 141–150, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21: 263–265, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson DK, Schneider J, Fourcaudot MJ, Rodriguez LM, Arya R, Dyer TD, Almasy L, Blangero J, Stern MP, Defronzo RA, Duggirala R, Jenkinson CP: Association between variants in the genes for adiponectin and its receptors with insulin resistance syndrome (IRS)-related phenotypes in Mexican Americans. Diabetologia 49: 2317–2328, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keene KL, Mychaleckyj JC, Leak TS, Smith SG, Perlegas PS, Divers J, Langefeld CD, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Sale MM: Exploration of the utility of ancestry informative markers for genetic association studies of African Americans with type 2 diabetes and end-stage renal disease. Hum Genet 124: 197–198, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keene KL, Mychaleckyj JC, Smith SG, Leak TS, Perlegas PS, Langefeld CD, Freedman BI, Rich SS, Bowden DW, Sale MM: Association of the distal region of the ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 gene with type 2 diabetes in an African-American population enriched for nephropathy. Diabetes 57: 1057–1062, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matarin M, Brown WM, Scholz S, Simon-Sanchez J, Fung HC, Hernandez D, Gibbs JR, De Vrieze FW, Crews C, Britton A, Langefeld CD, Brott TG, Brown RD Jr, Worrall BB, Frankel M, Silliman S, Case LD, Singleton A, Hardy JA, Rich SS, Meschia JF: A genome-wide genotyping study in patients with ischaemic stroke: initial analysis and data release. Lancet Neurol 6: 414–420, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, Liu-Cordero SN, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Cooper R, Ward R, Lander ES, Daly MJ, Altshuler D: The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 296: 2225–2229, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutton BS, Weinert S, Langefeld CD, Williams AH, Campbell JK, Saad MF, Haffner SM, Norris JM, Bowden DW: Genetic analysis of adiponectin and obesity in Hispanic families: the IRAS Family Study. Hum Genet 117: 107–118, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasseur F, Helbecque N, Dina C, Lobbens S, Delannoy V, Gaget S, Boutin P, Vaxillaire M, Lepretre F, Dupont S, Hara K, Clement K, Bihain B, Kadowaki T, Froguel P: Single-nucleotide polymorphism haplotypes in the both proximal promoter and exon 3 of the APM1 gene modulate adipocyte-secreted adiponectin hormone levels and contribute to the genetic risk for type 2 diabetes in French Caucasians. Hum Mol Genet 11: 2607–2614, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasseur F, Helbecque N, Lobbens S, Vasseur-Delannoy V, Dina C, Clement K, Boutin P, Kadowaki T, Scherer PE, Froguel P: Hypoadiponectinaemia and high risk of type 2 diabetes are associated with adiponectin-encoding (ACDC) gene promoter variants in morbid obesity: evidence for a role of ACDC in diabesity. Diabetologia 48: 892–899, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz PE, Govindarajalu S, Towers W, Schwanebeck U, Fischer S, Vasseur F, Bornstein SR, Schulze J: Haplotypes in the promoter region of the ADIPOQ gene are associated with increased diabetes risk in a German Caucasian population. Horm Metab Res 38: 447–451, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang WS, Yang YC, Chen CL, Wu IL, Lu JY, Lu FH, Tai TY, Chang CJ: Adiponectin SNP276 is associated with obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and diabetes in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr 86: 509–513, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heid IM, Wagner SA, Gohlke H, Iglseder B, Mueller JC, Cip P, Ladurner G, Reiter R, Stadlmayr A, Mackevics V, Illig T, Kronenberg F, Paulweber B: Genetic architecture of the APM1 gene and its influence on adiponectin plasma levels and parameters of the metabolic syndrome in 1,727 healthy Caucasians. Diabetes 55: 375–384, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woo JG, Dolan LM, Deka R, Kaushal RD, Shen Y, Pal P, Daniels SR, Martin LJ: Interactions between noncontiguous haplotypes in the adiponectin gene ACDC are associated with plasma adiponectin. Diabetes 55: 523–529, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Freedman BI, Arnett DK, Leiendecker-Foster C, Jones TL, Redden DT, Oberman A: Plasma adiponectin concentrations and correlates in African Americans in the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network (HyperGEN) study. Metabolism 56: 1011–1016, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz PE, Towers GW, Fischer S, Govindarajalu S, Schulze J, Bornstein SR, Hanefeld M, Vasseur F: Hypoadiponectinemia is associated with progression toward type 2 diabetes and genetic variation in the ADIPOQ gene promoter. Diabetes Care 29: 1645–1650, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.