Abstract

Kindler syndrome (KS) results from pathogenic loss-of-function mutations in the KIND1 gene, which encodes kindlin-1, a focal adhesion and actin cytoskeleton-related protein. How and why abnormalities in kindlin-1 disrupt keratinocyte cell biology in KS, however, is not yet known. In this study, we identified two previously unreported binding proteins of kindlin-1: kindlin-2 and migfilin. Co-immunoprecipitation and confocal microscopy studies show that these three proteins bind to each other and colocalize at focal adhesion in HaCaT cells and normal human keratinocytes. Moreover, loss-of-function mutations in KIND1 result in marked variability in kindlin-1 immunolabeling in KS skin, which is mirrored by similar changes in kindlin-2 and migfilin immunoreactivity. Kindlin-1, however, may function independently of kindlin-2 and migfilin, as loss of kindlin-1 expression in HaCaT keratinocytes by RNA interference and in KS keratinocytes does not affect KIND2 or FBLIM1 (migfilin) gene expression or kindlin-2 and migfilin protein localization. In addition to identifying protein-binding partners for kindlin-1, this study also highlights that KIND1 gene expression and kindlin-1 protein labeling are not always reduced in KS, findings that are relevant to the accurate laboratory diagnosis of this genodermatosis by skin immunohistochemistry.

INTRODUCTION

Kindler syndrome (KS; OMIM173650) is a rare autosomal recessive genodermatosis characterized by blistering in trauma-prone sites, photosensitivity, poikiloderma, and mucosal erosions and strictures (Kindler, 1954). The gene responsible for KS, KIND1, was identified in 2003 (Jobard et al., 2003; Siegel et al., 2003) and, to date, 32 different pathogenic KIND1 mutations have been documented (see Lai-Cheong et al., 2007 for mutation summary and Arita et al., 2007; Mansur et al., 2007 for additional recent mutations). The KIND1 gene encodes a 677 amino-acid protein, kindlin-1, which is expressed mainly in basal keratinocytes, colon, kidney, and placenta (Siegel et al., 2003). Kindlin-1 has been shown to associate with vinculin in the epithelial cell line PtK2 transiently transfected with EGFP-kindlin-1 and, to some extent, with filamentous actin (Siegel et al., 2003). Kindlin-1 forms complexes with β1- and β3-integrin cytoplasmic tails (Kloeker et al., 2004), and a reduction in kindlin-1 expression by RNA interference (RNAi) in HaCaT cells results in decreased cell spreading (Kloeker et al., 2004).

Kindlin-1 forms part of a family of kindlin proteins that includes two other members: kindlin-2 and kindlin-3 (Siegel et al., 2003). Kindlin-2 (also known as mitogen inducible gene-2; Mig2) associates with actin stress fibers and thus is a component of cell-extracellular matrix adhesion structures (Tu et al., 2003). RNAi studies, resulting in the knockdown of kindlin-2 expression in HeLa cells, have shown that kindlin-2 is required for the control of cell spreading, probably via integrin-linked kinase (Tu et al., 2003). Kindlin-2 has also been demonstrated to associate with and recruit migfilin at cell-matrix adhesions (Tu et al., 2003). Kindlin-3 is expressed in pulmonary and hematopoetic tissues but, thus far, has no known binding partners (Ussar et al., 2006). Migfilin is a novel LIM-containing protein that localizes to cell-matrix adhesions and associates with actin via its N-terminal domain while interacting with kindlin-2 through its C-terminal domain (Tu et al., 2003). Like kindlin-2, migfilin is critical for the control of cell shape (Tu et al., 2003) and has been shown to bind to filamin and vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (Zhang et al., 2006).

In this study, we have identified two key binding partners of kindlin-1, namely kindlin-2 and migfilin, and demonstrate both their tissue and cellular distribution. Furthermore, we have shown that not every patient with KS with pathogenic KIND1 mutations has reduced immunolabeling for kindlin-1, with some individuals having normal levels of kindlin-1 expression and yet suffering from KS. These observations provide further insight into the role of kindlin-1 in pathophysiology of KS.

RESULTS

Clinical features of KS patients

The clinical features of the 13 patients with KS assessed in this study are summarized in Table 1. All these individuals have previously determined loss-of-function mutations on both KIND1 alleles.

Table 1. Summary of ethnicity, clinical features, KIND1 mutations, and skin immunostaining patterns for anti-kindlin-1, anti-kindlin-2, and anti-migfilin antibodies in 13 patients with KS.

| Immunolabeling |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | KIND1 mutations | Blistering | Skin atrophy |

Poikilo- derma |

Photo- sensitivity |

Gingival inflammation |

Urethral stenosis |

Kindlin- 1 |

Kindlin- 2 |

Migfilin | Reference |

| Indian | p.C468X/ p.C468X |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ± | ++ | − | Sethuraman et al., 2005 |

| Indian | p.E516X/ p.E516X |

Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | ± | ++ | − | Lai-Cheong et al., 2007 |

| Omani | p.R271X/ p.R271X |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | + | + | − | Siegel et al., 2003 |

| Omani | p.W616X/ p.W616X |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | + | + | + | Ashton et al., 2004 |

| Omani | p.W616X/ p.W616X |

Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | + | ++ | + | Ashton et al., 2004 |

| Brazilian | c.676insC/ c.676insC |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + | ++ | ± | Martignago et al., 2007 |

| US Caucasian | p.R271X/ c.1755delT |

Y | Y | Y | NK | Y | Y | + | ++ | − | Siegel et al., 2003 |

| US Caucasian | p.E304X/ c.1188insT |

Y | Y | Y | Y | NK | Y | +++ | +++ | +++ | Ashton et al., 2004 |

| US Caucasian | p.E304X/ c.1161delA |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | +++ | ++ | ++ | Ashton et al., 2004 |

| UK Caucasian | p.E304X/ c.1909delA |

Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | ++ | +++ | +++ | Ashton et al., 2004 |

| UK Caucasian | p.R288X/ p.R288X |

Y | Y | Y | Y | NK | Y | +++ | +++ | +++ | Siegel et al., 2003 |

| UK Caucasian | p.E304X/ p.L302X |

Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | +++ | +++ | +++ | Ashton et al., 2004 |

| Italian | IVS7-1G>A/ IVS7-1G>A |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | +++ | +++ | +++ | Ashton et al., 2004 |

| NHS | WT/WT | N | N | N | N | N | N | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

N, no; NK, not known; NHS, normal human skin; Y, yes; WT, wild type.

+++, bright immunostaining; ++, slight reduction in immunoreactivity; +, marked reduction in immunostaining; ±, barely detectable immunolabeling; −, complete absence of labeling.

Immunoblotting reveals expression of kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin in HaCaT cells, normal human keratinocytes (NHK), and KS keratinocytes

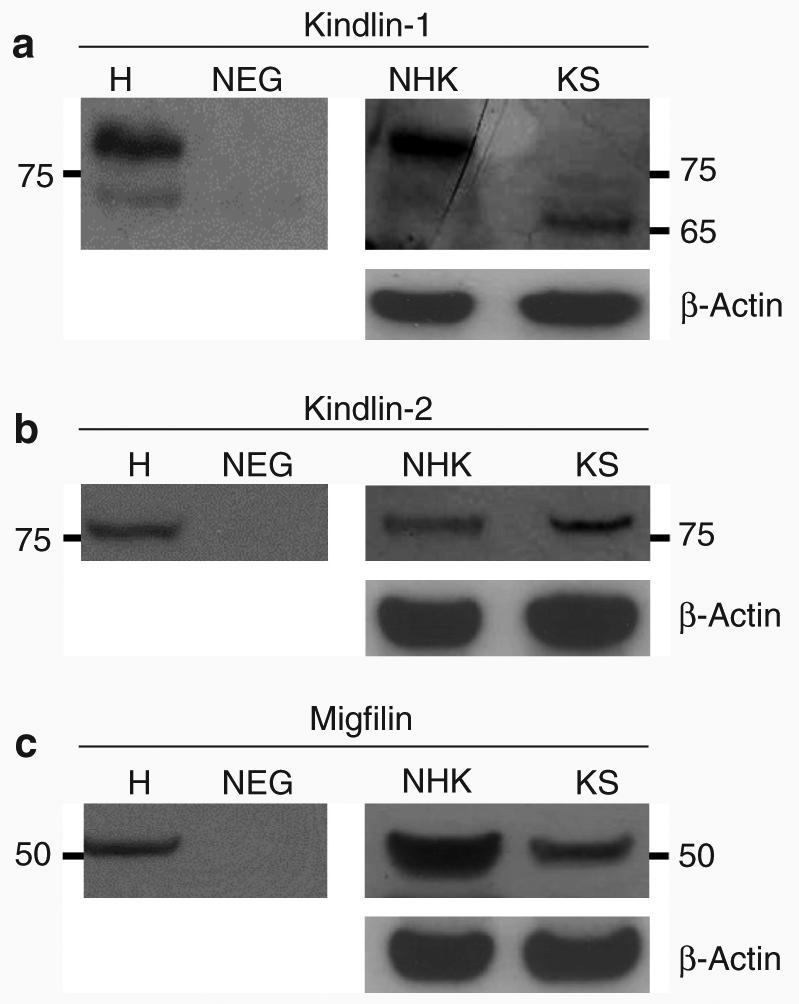

Western blotting showed that kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin were expressed in both HaCaT cells, a spontaneously immortalized human keratinocyte cell line (Boukamp et al., 1988), and in NHK. Discrete bands of ∼77 kDa were noted for both kindlin-1 (Figure 1a, lanes H and NHK) and kindlin-2 (Figure 1b, lanes H and NHK) and an ∼50 kDa band was detected for migfilin (Figure 1c, lanes H and NHK) in HaCaT and NHK lysates. Additionally, in HaCaT lysate, there was an ∼74 kDa band that may correspond to the dephosphorylated form of the kindlin-1 protein (Herz et al., 2006). In KS keratinocyte lysate, there was loss of the ∼77 kDa band, a finding that confirmed the specificity of this kindlin-1 protein band (Figure 1a, lane KS). In the same KS lysate, however, a different ∼65 kDa protein band was observed. Although the nature of this band is currently unknown, it may correspond to a truncated or alternatively spliced form of the protein.

Figure 1. Immunoblotting shows different expression patterns of kindlin-1 (but not kindlin-2 or migfilin) in KS or control keratinocytes.

Immunoblotting shows (a) ∼77 and ∼74 kDa protein bands matching the molecular weight of kindlin-1 and its dephosphorylated form in HaCaT cell lysate (lane H). The same ∼77 kDa band was present in lane NHK but absent in lane KS. In addition, an ∼65 kDa band was seen in lane KS. (b) In lanes H, NHK, and KS, an ∼77 kDa band corresponding to the molecular weight of kindlin-2 was seen. (c) An ∼50 kDa band that equates to the expected molecular weight of migfilin was observed in lanes H, NHK, and KS. H, HaCaT cell lysate; NEG, negative control; NHK, normal human keratinocytes; KS, Kindler syndrome.

Co-immunoprecipitation studies identify kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin as potential biochemical partners

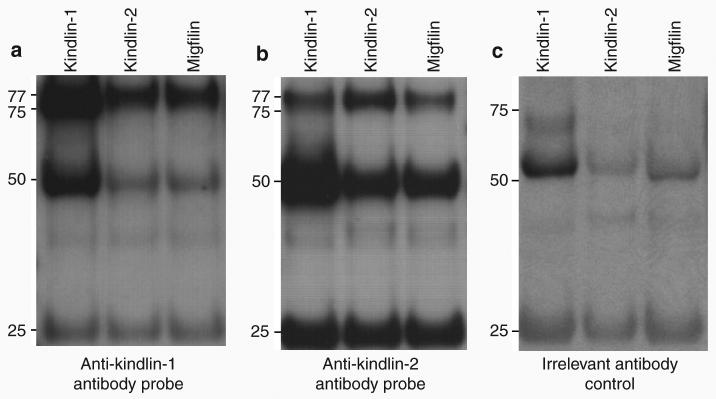

We focused on kindlin-2 and migfilin as potential kindlin-1-binding partners, as they have previously been shown to be components of cell-matrix adhesions as well as being biochemically related to each other (Tu et al., 2003; Wu 2005). To determine whether these three proteins are biochemical partners, co-immunoprecipitation was performed on HaCaT cell lysates, which were precipitated separately with anti-kindlin-1, anti-kindlin-2, and anti-migfilin antibodies. When anti-kindlin-1 antibody was used to probe the blot, an ∼77 kDa band was detected not only for kindlin-1 but also for kindlin-2 and migfilin (Figure 2a). Similar patterns of reactivity were observed when anti-kindlin-2 antibody was used to probe the blot (Figure 2b). In both blots, there were protein bands at ∼50 and ∼25 kDa corresponding to the molecular weight of heavy- and light-chain immunoglobulins, respectively. Western blotting of the same immunoprecipitates using a rabbit polyclonal anti-collagen VII antibody as an irrelevant antibody control showed the absence of protein bands at ∼77 kDa but the continued presence of bands corresponding to the heavy- and light-chain immunoglobulins, respectively (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Co-immunoprecipitation studies show that kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin can bind to each other.

(a) Western blotting on the immunoprecipitates using anti-kindlin-1 antibody shows ∼77 kDa bands in all three lanes, indicating that kindlin-1 forms a complex with kindlin-2 and migfilin. (b) Similarly, western blotting using anti-kindlin-2 antibody reveals ∼77 kDa bands in all three lanes, indicating that kindlin-2 associates with kindlin-1 and migfilin. (c) Immunoblotting performed using rabbit polyclonal anti-collagen VII IgG antibody as irrelevant antibody control shows absence of the ∼77 kDa protein band but persistence of the ∼50 and ∼25 kDa bands.

Confocal microscopy studies show that kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin colocalize at focal contacts in NHK and HaCaT cells

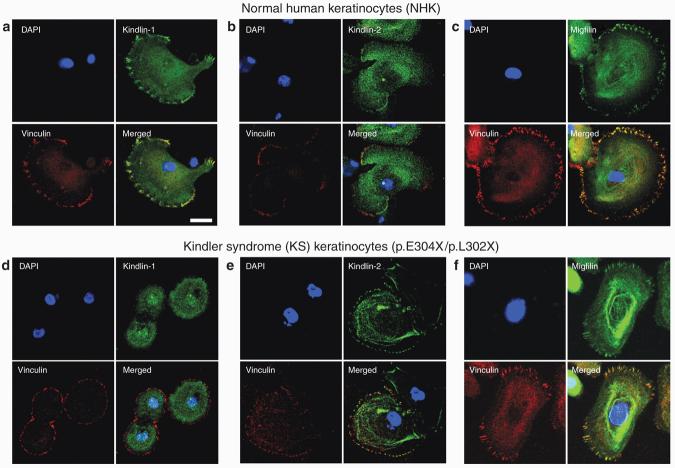

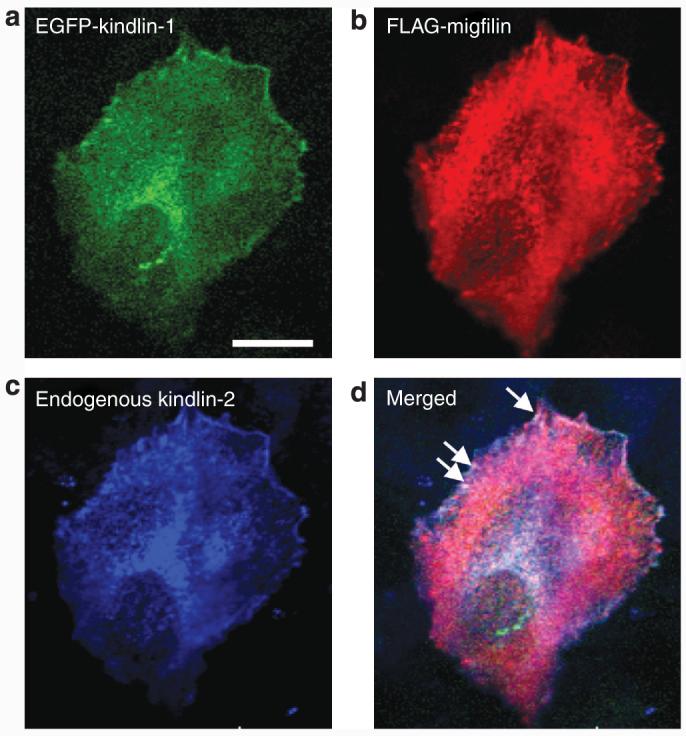

To determine whether kindlin-1 colocalizes with its two biochemical partners, confocal microscopy studies were performed on NHK individually labeled with anti-kindlin-1, anti-kindlin-2, or anti-migfilin antibody. Focal adhesions were revealed by double-staining the cells with anti-vinculin antibody. In NHK, kindlin-1 showed diffuse cytoplasmic expression and punctate nuclear localization and colocalized with vinculin (Figure 3a). In addition, kindlin-2 and migfilin were expressed in the cytoplasm as well as at focal adhesions (Figures 3b and c). The independent colocalization of kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin with vinculin suggests that all three proteins may colocalize with each other. To assess this, confocal microscopy imaging was performed on HaCaT cells co-transfected with EGFP-kindlin-1 (Figure 4a) and FLAG-migfilin (Figure 4b) and then immunostained with anti-kindlin-2 antibody (Figure 4c). The merged image showed that the three proteins colocalized at focal adhesions (Figure 4d).

Figure 3. Confocal microscopy studies show different kindlin-1 localization but preserved kindlin-2 and migfilin localization in NHK and KS keratinocytes, respectively.

(a) In NHK, kindlin-1 was expressed both in the cytoplasm and near the cell periphery and colocalized with vinculin at focal adhesions. Similarly, both (b) kindlin-2 and (c) migfilin showed cytoplasmic and peripheral distribution and colocalized with vinculin. (d) In KS keratinocytes, there was cytoplasmic localization of kindlin-1 but kindlin-1 expression at focal adhesions was absent, as evidenced by the lack of colocalization with vinculin. In contrast, (e) kindlin-2 and (f) migfilin subcellular localization was not affected. Bar = 20 μm.

Figure 4. Confocal microscopy shows that kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin all colocalize at focal adhesions.

(a) Kindlin-1 localizes to the ends of actin stress fibers and also demonstrates a perinuclear distribution. (b) Migfilin is distributed both in the cytoplasm and at the cell periphery. (c) Endogenous kindlin-2 also localizes to the ends of actin stress fibers. (d) Merged confocal image shows colocalization of kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin at focal adhesions as shown by the white staining at the cell periphery (arrows). Bar = 20 μm.

Confocal microscopy studies on primary KS keratinocytes show loss of kindlin-1 expression at focal adhesions but presence of kindlin-2 and migfilin

To explore the pathophysiological role of kindlin-1 and its two potential binding partners in KS, confocal microscopy analysis was performed on primary KS keratinocytes (harboring compound heterozygous KIND1 mutations, p.E304X/p.L302X) immunolabeled separately with anti-kindlin-1, anti-kindlin-2, and anti-migfilin antibodies. In these KS keratinocytes, kindlin-1 no longer colocalized with vinculin at focal adhesions despite cytoplasmic expression being present. However, nuclear localization of kindlin-1 was still present in these cells (Figure 3d). In contrast, kindlin-2 and migfilin still colocalized with vinculin at focal adhesion (Figures 3e and f).

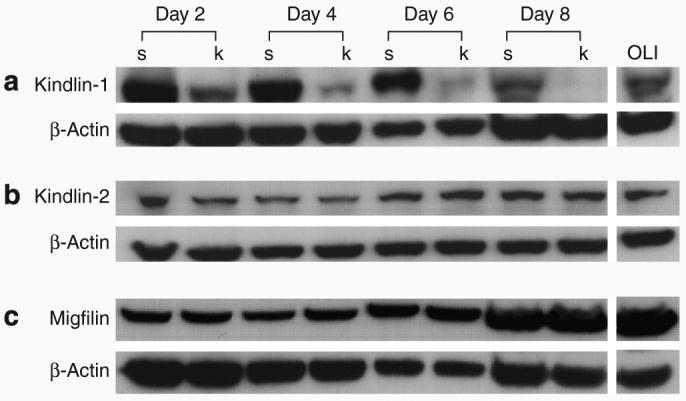

Knockdown of kindlin-1 by RNAi does not alter expression of kindlin-2 or migfilin in HaCaT cells

To understand the consequences of loss of kindlin-1 expression on kindlin-2 and migfilin, an RNAi study was performed in HaCaT cells using kindlin-1 (k) and scrambled control (s) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) at a concentration of 100 nm. A gradual reduction in kindlin-1 expression was observed from day 2 post-transfection to almost complete knockdown at day 8 (Figure 5a). However, the reduction of kindlin-1 did not alter the expression of kindlin-2 (Figure 5b). An increase in migfilin expression was noted from day 6 post-transfection in both the scrambled and kindlin-1-transfected HaCaT cells, as well as in the oligofectamine-transfected cells (Figure 5c). This was confirmed by optical densitometry analysis using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), which showed up to a fourfold increase in migfilin compared with day 2 transfected cells (data not shown). The increase in migfilin expression occurred in both the scrambled control and kindlin-1-transfected cells, suggesting therefore that it is not a consequence of kindlin-1 knockdown.

Figure 5. Kindlin-2 and migfilin expression is not altered after RNAi-mediated knockdown of kindlin-1 in HaCaT cells.

(a) Gradual reduction of kindlin-1 expression was noted from day 2 post-transfection. (b) Expression of kindlin-2 does not seem to be altered by kindlin-1 knockdown. (c) However, there was an increase in migfilin expression from day 6 post-transfection in the scrambled control and kindlin-1-transfected HaCaT cells. Oligofectamine-only (OLI)-treated HaCaT keratinocytes lysate was used as control and showed no reduction in kindlin-1 expression. In contrast, no reduction in kindlin-1 expression was seen when the cells were treated with scrambled siRNA.

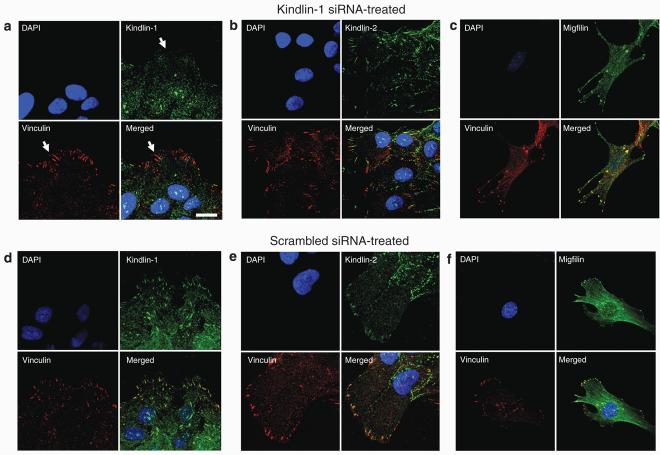

Kindlin-2 and migfilin localization is unchanged following kindlin-1 siRNA transfection of HaCaT keratinocytes

Confocal microscopy studies performed on kindlin-1 siRNA-treated HaCaT keratinocytes showed loss of kindlin-1 localization at focal adhesions (Figure 6a, arrows). However, diffuse cytoplasmic staining of kindlin-1 was still seen. In contrast, kindlin-2 and migfilin still colocalized at focal adhesions (Figures 6b and c). In the scrambled control siRNA-treated cells, colocalization of kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin with vinculin at focal adhesions was still present, with no change in the protein distribution or appearances of focal adhesions (Figures 6d–f).

Figure 6. Kindlin-2 and migfilin localization remains unchanged in kindlin-1 siRNA-transfected HaCaT keratinocytes.

(a) In HaCaT keratinocytes transfected with kindlin-1 siRNA, there was no localization of kindlin-1 at focal adhesions (arrows). However, (b) kindlin-2 and (c) migfilin still colocalized with vinculin at focal adhesions. In contrast, in the scrambled control-transfected HaCaT cells, there was no change in (d) kindlin-1, (e) kindlin-2, and (f) migfilin subcellular localization. Bar = 20 μm.

Immunofluorescence microscopy shows highly variable kindlin-1 immunostaining in KS patients with pathogenic KIND1 mutations

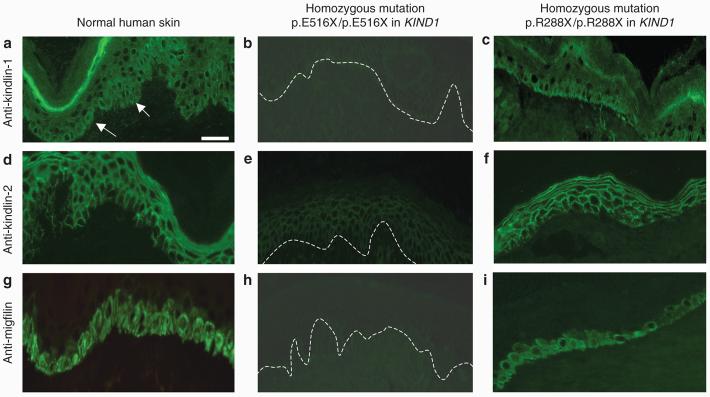

To determine the tissue distribution of kindlin-1, immunofluorescence microscopy labeling was performed in both normal and KS frozen skin sections. In normal skin sections immunolabeled with anti-kindlin-1 antibody, there was bright staining near the cell periphery in the basal keratinocytes (arrows) as well as less intense labeling throughout the epidermis (Figure 7a). Frozen skin sections from 13 patients with KS with pathogenic KIND1 mutations were immunolabeled for kindlin-1. A surprising finding was that not every patient showed reduced or absent anti-kindlin-1 immunostaining. In fact, kindlin-1 labeling was markedly reduced in seven patients (Figure 7b) and was normal or only slightly reduced in six patients with KS (Figure 7c). The immunofluorescence microscopy data are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 7. Immunofluorescence microscopy shows two patterns of labeling for kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin in KS skin.

(a) Immunolabeling with anti-kindlin-1 antibody on normal skin sections shows bright epidermal staining predominantly at the cell periphery (but also in the cytoplasm) mostly within the basal keratinocyte layer (arrows) but with less intense pan-epidermal labeling. (b) In the KS patient with the homozygous nonsense mutation p.E516X/p.E516X there is barely detectable staining for kindlin-1. (c) In contrast, in the KS patient with the homozygous mutation p.R288X/p.R288X there is similar kindlin-1 immunolabeling intensity to control skin (cf. Figure 7a). (d) Anti-kindlin-2 immunostaining of normal skin sections shows pan-epidermal membranous labeling with the absence of staining being noted along the lower pole of basal keratinocytes. (e) Marked reduction in anti-kindlin-2 antibody immunoreactivity is seen in the patient's skin harboring the homozygous nonsense mutation p.E516X/p.E516X. (f) Kindlin-2 antibody labeling in the patient with the homozygous nonsense mutation p.R288X/p.R288X is similar to that in normal skin. (g) Anti-migfilin staining of normal skin sections shows membranous and cytoplasmic labeling of the basal keratinocytes. (h) Anti-migfilin antibody labeling in the patient with homozygous nonsense mutation p.E516X/p.E516X shows barely detectable labeling. (i) Anti-migfilin antibody labeling in the patient with the homozygous nonsense mutation p.R288X/p.R288X is similar to that in normal skin. White dashed lines indicate the position of the dermal–epidermal junction in (b), (e), and (h). Bar = 50 μm.

Immunolabeling for kindlin-2 and migfilin in KS skin mirrors the variable kindlin-1 immunostaining patterns

Immunostaining with anti-kindlin-2 antibody on frozen normal skin sections showed pan-epidermal membranous labeling but with no staining along the lower pole of basal keratinocytes in contact with the basement membrane (Figure 7d). Anti-migfilin antibody labeling on frozen normal skin sections showed basal epidermal staining near the cell periphery with sparing of the rest of the epidermis (Figure 7g). Of note, there was a reduction of immunolabeling for kindlin-2 (Figure 7e) and also migfilin (Figure 7h) in the seven patients with KS with reduced anti-kindlin-1 labeling. However, in the six patients in whom kindlin-1 labeling was normal or slightly reduced, kindlin-2 and migfilin immunostaining was of normal or near-normal intensity (Figures 7f and i). Table 1 provides a summary of the immunolabeling data.

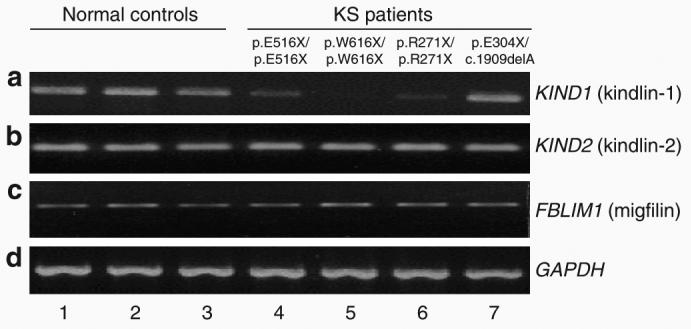

Semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) shows variable reduction in KIND1 mRNA expression but normal KIND2 and FBLIM1 (migfilin) mRNA levels

To begin to understand why some patients with KS have reduced or almost normal anti-kindlin-1 immunostaining patterns, we assessed KIND1 mRNA expression in four patients with KS, all of whom had pathogenic KIND1 mutations determined in their genomic DNA. RT-PCR was performed using cDNA synthesized from skin samples from three patients with reduced or absent anti-kindlin-1 immunolabeling and one patient with near-normal immunostaining, respectively. The three patients harboring the following homozygous nonsense mutations p.E516X/p.E516X, p.W616X/p.W616X, and p.R271X/p.R271X all had reduced anti-kindlin-1 immunolabeling and were found to have correspondingly decreased expression of full-length KIND1 mRNA (Figure 8a, lanes 4–6). The reduction in KIND1 mRNA in these cases is consistent with nonsense-mediated RNA decay (Nagy and Maquat, 1998; Frischmeyer and Dietz, 1999; Holbrook et al., 2004; Maquat 2004), notwithstanding that the mutation p.W616X occurs close to the 3′ end of the penultimate KIND1 exon (exon 14). Whole skin cDNA was available only from one patient with normal kindlin-1 immunostaining (harboring the compound heterozygous mutations p.E304X/c.1909delA) who was subsequently found to have normal expression of KIND1 mRNA (Figure 8, lane 7). However, all four patients had normal levels of KIND2 and FBLIM1 (migfilin) mRNA levels compared with normal controls (Figures 8b and c) despite the individuals in lanes 4–6 showing reduced kindlin-2 and migfilin labeling on skin sections (cf. Figure 7e and h).

Figure 8. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR shows correlation between KIND1 mRNA expression and the corresponding kindlin-1 labeling patterns.

(a) Compared with the three normal controls (lanes 1–3), patients with reduced anti-kindlin-1 immunostaining (lanes 4–6) had variably reduced KIND1 mRNA levels, whereas the patient with normal immunolabeling of anti-kindlin-1 (lane 7) had a normal or near-normal level of KIND1 mRNA. (b) Patients with reduced kindlin-2 labeling (lanes 4–6), however, had no reduction in KIND2 mRNA expression compared with normal controls (lanes 1–3) or the patient with normal kindlin-2 immunostaining (lane 7). (c) Similarly, there was no difference in FBLIM1 mRNA expression in any of the patients compared with normal controls. (d) GAPDH mRNA expression was used as loading control in these experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified kindlin-2 and migfilin as two novel biochemical partners of kindlin-1 by co-immunoprecipitation supported by confocal microscopy imaging on NHK, KS keratinocytes, as well as on transfected HaCaT cells. Previous studies have established the colocalization of kindlin-1 with other focal adhesion proteins such as paxillin in various cell types including mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Ussar et al., 2006) and the epithelial cell line PtK2 (Siegel et al., 2003). However, our confocal microscopy studies provide novel in vitro data regarding the localization of kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin in both NHK and KS keratinocytes. Additionally, we have shown that loss of kindlin-1 in both KS keratinocytes and kindlin-1 siRNA-transfected HaCaT cells does not seem to alter the expression or localization of either kindlin-2 or migfilin at focal adhesions.

Our study also identifies a potential pitfall in using immunofluorescence microscopy to assist the clinical diagnosis of KS. Previously, our group has reported the usefulness of immunofluorescence microscopy on frozen skin sections in making a rapid diagnosis of KS (Ashton et al., 2004; Fassihi et al., 2005; Burch et al., 2006; Arita et al., 2007). Although it remains an invaluable tool, immunostaining of a larger number of cases now highlights that some patients with KS, with loss-of-function KIND1 mutations confirmed by gene sequencing, have almost normal anti-kindlin-1 immunostaining. Thus, positive anti-kindlin-1 immunolabeling does not rule out a diagnosis of KS, and therefore KIND1 gene sequencing remains the gold standard in diagnosing this condition. An explanation for the positive anti-kindlin-1 antibody labeling may be gleaned from immunoblotting data comparing kindlin-1 expression in NHK and KS lysates (obtained from an individual with KS harboring compound heterozygous KIND1 mutations, p.E304X/p.L302X). In this individual, positive anti-kindlin-1 skin immunolabeling was observed, which may reflect the presence of the ∼65 kDa protein band detected by immunoblotting. Although the nature of this band is currently unknown, it could correspond to either a smaller kindlin-1 isoform or a truncated form of the protein, or it could represent nonspecific antibody binding.

The immunofluorescence data also raise several key points. First, there does not appear to be any clear correlation between the site or nature of the mutations, immunostaining patterns, and specific clinical features of the disease. For instance, the patients with the homozygous nonsense mutations p.R271X/p.R271X and p.R288X/p.R288X might be predicted to have similar immunostaining patterns, but our results suggest otherwise. Secondly, the seven patients with reduced or absent anti-kindlin-1 immunostaining had similar clinical features to those with positive immunolabeling, observations which suggest that the low levels of kindlin-1 expression or normally expressed but defective kindlin-1 protein are insufficient to maintain normal skin integrity and homeostasis. Thirdly, it appears that patients of Caucasian background have more positive anti-kindlin-1 immunostaining compared with other affected individuals (for example, from the Middle East, South America, or Asia), suggesting that the diverse ethnic, geographical, and environmental backgrounds of the cases studied may also have an impact on phenotype and expression of kindlin-1. Fourthly, although skin immunolabeling reveals a mirror effect for kindlin-1, kindlin-2, and migfilin immunolabeling (that is, a reduction of kindlin-1 labeling is paralleled by a decrease in both kindlin-2 and migfilin labeling), kindlin-2 or migfilin expression and localization were still demonstrated by immunoblotting and confocal microscopy, respectively.

KIND1 mRNA expression was variably reduced in the three patients with reduced anti-kindlin-1 labeling. However, the individual harboring the compound heterozygous mutations p.E304X/c.1909delA (normal anti-kindlin-1 labeling) had near-normal KIND1 mRNA expression. In this case, we anticipated KIND1 mRNA expression to be ∼50% of normal, as the mutation c.1909delA occurs in the last exon of KIND1 and is therefore unlikely to be affected by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. However, KIND1 mRNA levels were normal, suggesting that the other mutation p.E304X in exon 7 also does not seem to affect the stability of KIND1 mRNA. No evidence for alternative splicing of KIND1 was detected in this individual, and thus an adequate explanation for the near-normal mRNA levels is lacking.

The identification of kindlin-2 and migfilin as binding partners of kindlin-1 provides new insight into the pathophysiology of KS. First, it is evident that not all cases of KS harbor pathogenic mutations in KIND1—perhaps ∼25% of cases may result from mutations in other, as yet unidentified, candidate genes (JAM, unpublished data). It is therefore plausible that some individuals with KS or a KS-like genodermatosis might have underlying pathogenic mutations in KIND2 or FBLIM1. Secondly, the biochemical association of these proteins provides new information regarding the role of focal adhesion proteins in the pathogenesis of skin disease and helps us understand further the pathophysiology of KS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

A rabbit polyclonal anti-kindlin-1 antibody that recognizes the last 277 amino-acid residues of kindlin-1 was kindly supplied by Dr Mary Beckerle (Salt Lake City, OH). Rabbit polyclonal anti-kindlin-2 and anti-migfilin antibodies were supplied by Reinhard Fässler (Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany). Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) was used for immunofluorescence labeling on skin sections. For cell immunofluorescence staining, mouse monoclonal anti-vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and anti-FLAG M2 antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Invitrogen), both highly cross-adsorbed, were used in cell immunofluorescence microscopy.

Skin biopsies

Skin biopsies were taken for immunofluorescence microscopy studies, tissue culture, and nucleic acid extraction after written, informed consent was obtained from each patient, in accordance with the Ethics Committee approval from the Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Western blotting

Keratinocytes were lysed with NuPage LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 10% 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were then loaded and run on NuPage 4–12% bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) at 150 V for 1.5 hours. The proteins were then transferred onto Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK) and blocked in 5% skimmed milk in 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) and Tris-buffered saline. The membranes were then probed with anti-kindlin-1, anti-kindlin-2, and anti-migfilin antibodies overnight at 4°C. Mouse monoclonal anti-β actin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as loading control. Anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG antibody was used as secondary antibody. Visualization of protein bands was done with ECL western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Co-immunoprecipitation

For co-immunoprecipitation, confluent HaCaT cell culture in 75 cm2 flask was lysed with 500 μl of Ripa (Radioimmunoprecipitation assay) lysis buffer (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Charlottesville, VA) containing 5 μl of 100 mm protease inhibitor cocktail set (Merck Bioscience, Nottingham, UK) and 5 μl of 100 mm sodium orthovanadate at 4°C for 5 minutes. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was precleared with Trueblot anti-rabbit Ig immunoprecipitation beads (Insight Biotechnology Ltd, Middlesex, UK) for 30 minutes at 4°C. The beads were then removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was mixed separately with anti-kindlin-1, anti-kindlin-2, and anti-migfilin antibodies for 1 hour at 4°C. Subsequently, Trueblot anti-rabbit Ig immunoprecipitation beads were added to the immunoprecipitates and incubated on ice for a further hour. The beads were then collected by centrifugation and washed three times with Ripa buffer before proceeding with western blotting. Rabbit Trueblot HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG was used as secondary antibody (Insight Biotechnology Ltd). Visualization of protein bands was achieved with ECL western Blotting detection reagents.

Plasmid transfection of HaCaT cells

EGFP-kindlin-1, EGFP-kindlin-2, and FLAG-migfilin were supplied by Professor Reinhard Fässler. EGFP-kindlin-1 and EGFP-kindlin-2 were cloned as described previously (Ussar et al., 2006). HaCaT keratinocytes, at a seeding density of 2×105 cells per well on 13 mm diameter coverslips in a 6-well plate, were transfected with EGFP-kindlin-1 and FLAG-migfilin. Briefly, 1 μg of each plasmid was mixed with 500 μl of Optimem (Gibco, Paisley, UK) and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. A volume of 5 μl of oligofectamine (Invitrogen) was added to 500 μl optimem and the mixture was incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. The two solutions were then mixed, incubated for a further 20 minutes at room temperature before being added to the HaCaT keratinocytes, and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours.

Cell immunofluorescence microscopy

For immunofluorescence, the fixed cells (fixation achieved using either 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature or an equal mixture of methanol/acetone for 10 minutes at −20°C) were blocked with 10% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.3% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline by incubation with primary antibody. Secondary antibody incubation was performed for 1 hour at room temperature. The coverslips containing the fixed immunolabeled cells were mounted with Prolong Gold AntiFade Reagent (Invitrogen) onto Superfrost Plus slides (VWR) and analyzed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 Imaging confocal microscopy system.

RNA interference

Kindlin-1 expression was knocked down by RNAi using kindlin-1 siRNA (Dharmacon/Perbio, Cramlington, UK) as described previously (Kloeker et al., 2004). Preparation of the transfectants involved incubating each siRNA with Optimem for 5 minutes at room temperature before adding the mixture to an oligofectamine/Optimem solution. The cells were incubated for 4 hours with this transfection mixture.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Five-micrometer-thick frozen skin sections were cut from skin biopsies obtained from 13 patients with KS in whom loss-of-function mutations in KIND1 had been determined. The sections were blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 minutes followed by incubation with the primary antibody for 30 minutes at 37°C. Secondary antibody incubation was performed for 30 minutes at 37°C. Following phosphate-buffered saline wash, the sections were air-dried and mounted with Vectashield Hard Set with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) and viewed under a fluorescent microscope.

Extraction of total RNA from skin biopsies and cDNA synthesis

Skin biopsies were taken from patients with KS harboring the mutations p.E516X/p.E516X, p.W616X/p.W616X, p.R271X/p.R271X, and p.E304X/c.1909delA, and stored in RNAlater (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) before processing. Total RNA was extracted from each skin biopsy using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 2 μg of total RNA using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen).

Semi-quantitative PCR analysis

First-strand cDNA was amplified by PCR in a reaction volume consisting of 2 μl of 2.5 m dNTP, 2 μl forward and reverse primers, 1 μl of cDNA, 10.375 μl water, 0.125 μl of Taq polymerase, 5 μl Q buffer, and 2.5 μl of 10× buffer. All PCR reagents were purchased from Qiagen. Details of KIND1, KIND2, and FBLIM1 cDNA primers are as follows: KIND1 forward cDNA primer: 5′-TCAAACAGTGGAATGTAAACTGG-3′; KIND1 reverse cDNA primer: 5′-TACATGCTGGGCACGTTAGG-3′; KIND2 forward cDNA primer: 5′-GAACAAGCAGATAACAGC-3′; KIND2 reverse cDNA primer: 5′-CGGTGACCATTTTGATTTCCC-3′; FBLIM1 forward cDNA primer: 5′-AAAATCGAATGCATGGGAAG-3′; FBLIM1 reverse cDNA primer: 5′-GCAGGTTAGGAAGGGAAACC-3′. All the primer pairs were designed to amplify a region in the 3′ UTR of each gene and were purchased from MWG (Ebelsberg, Germany). To ensure equal loading, a housekeeping gene (GAPDH) was simultaneously amplified. The PCR products were assessed on a 2% agarose gel.

HaCaT culture

The HaCaT cell line was grown to 70–80% confluence in DMEM (Invitrogen) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen).

Primary keratinocyte culture

Skin biopsies were incubated overnight at 4°C with dispase I (dilution 34 U in 20 ml phosphate-buffered saline) (Roche Applied Science, Burgess Hill, UK). The detached epidermal sheet was then incubated with a 0.05% tryspin/EDTA solution (Invitrogen) for 15 minutes at 37°C. The solution was subsequently filtered through a 100 μm cell strainer (VWR International, Lutterworth, UK) and the released keratinocytes were centrifuged at 1200 r.p.m. for 5 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended in Epilife Basal Medium (Cascade Biologics, Mansfield, UK) supplemented with Epilife Defined Growth Supplement and Gentamicin/Amphotericin B (Cascade Biologics) and plated in T25 flasks previously treated with Coating Matrix (Cascade Biologics).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.L.-C. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship. Additional funding support from the Barbara Ward Childrens' Foundation and the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DebRA, UK) is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- KS

Kindler syndrome

- NHK

normal human keratinocytes

- RNAi

RNA interference

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Arita K, Wessagowit V, Inamadar AC, Palit A, Fassihi H, Lai-Cheong JE, et al. Unusual molecular findings in Kindler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1252–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton GH, McLean WH, South AP, Oyama N, Smith FJ, Al-Suwaid R, et al. Recurrent mutations in kindlin-1, a novel keratinocyte focal contact protein, in the autosomal recessive skin fragility and photosensitivity disorder, Kindler syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:78–83. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:761–71. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch JM, Fassihi H, Jones CA, Mengshol SC, Fitzpatrick JE, McGrath JA. Kindler syndrome: a new mutation and new diagnostic possibilities. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:620–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassihi H, Wessagowit V, Jones C, Dopping-Hepenstal P, Denyer J, Mellerio JE, et al. Neonatal diagnosis of Kindler syndrome. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;39:183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischmeyer PA, Dietz HC. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in health and disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1893–900. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz C, Aumailley M, Schulte C, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Has C. Kindlin-1 is a phosphoprotein involved in regulation of polarity, proliferation, and motility of epidermal keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36082–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook JA, Neu-Yilik G, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. Nonsense-mediated decay approaches the clinic. Nat Genet. 2004;36:801–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobard F, Bouadjar B, Caux F, Hadj-Rabia S, Has C, Matsuda F, et al. Identification of mutations in a new gene encoding a FERM family protein with a pleckstrin homology domain in Kindler syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:925–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler T. Congenital poikiloderma with traumatic bulla formation and progressive cutaneous atrophy. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:104–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1954.tb12598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloeker S, Major MB, Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH, Jones DA, Beckerle MC. The Kindler syndrome protein is regulated by transforming growth factor-beta and involved in integrin-mediated adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6824–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai-Cheong JE, Liu L, Sethuraman G, Kumar R, Sharma VK, Reddy SR, et al. Five new homozygous mutations in the KIND1 gene in Kindler syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2268–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansur AT, Elcioglu NH, Aydingöz IE, Akkaya AD, Serdar ZA, Herz C, et al. Novel and recurrent KIND1 mutations in two patients with Kindler syndrome and severe mucosal involvement. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:563–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquat LE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nrm1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martignago BC, Lai-Cheong JE, Liu L, McGrath JA, Cestari TF. Recurrent KIND1 (C20orf42) gene mutation, c.676insC, in a Brazilian pedigree with Kindler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1281–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy E, Maquat LE. A rule for termination-codon position within introns containing genes: when nonsense affects RNA abundance. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:198–9. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman G, Fassihi H, Ashton GH, Bansal A, Kabra M, Sharma VK, et al. An Indian child with Kindler syndrome resulting from a new homozygous nonsense mutation (C468X) in the KIND1 gene. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:286–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DH, Ashton GH, Penagos HG, Lee JV, Feiler HS, Wilhelmsen KC, et al. Loss of kindlin-1, a human homolog of the Caenorhabditis elegans actin-extracellular-matrix linker protein UNC-112, causes Kindler syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:174–87. doi: 10.1086/376609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y, Wu S, Shi X, Chen K, Wu C. Migfilin and Mig-2 link focal adhesions to filamin and the actin cytoskeleton and function in cell shape modulation. Cell. 2003;113:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussar S, Wang HV, Linder S, Fässler R, Moser M. The Kindlins: subcellular localization and expression during murine development. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3142–51. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. Migfilin and its binding partners: from cell biology to human diseases. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:659–64. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Tu Y, Gkretsi V, Wu C. Migfilin interacts with vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) and regulates VASP localization to cell-matrix adhesions and migration. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12397–407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]