Abstract

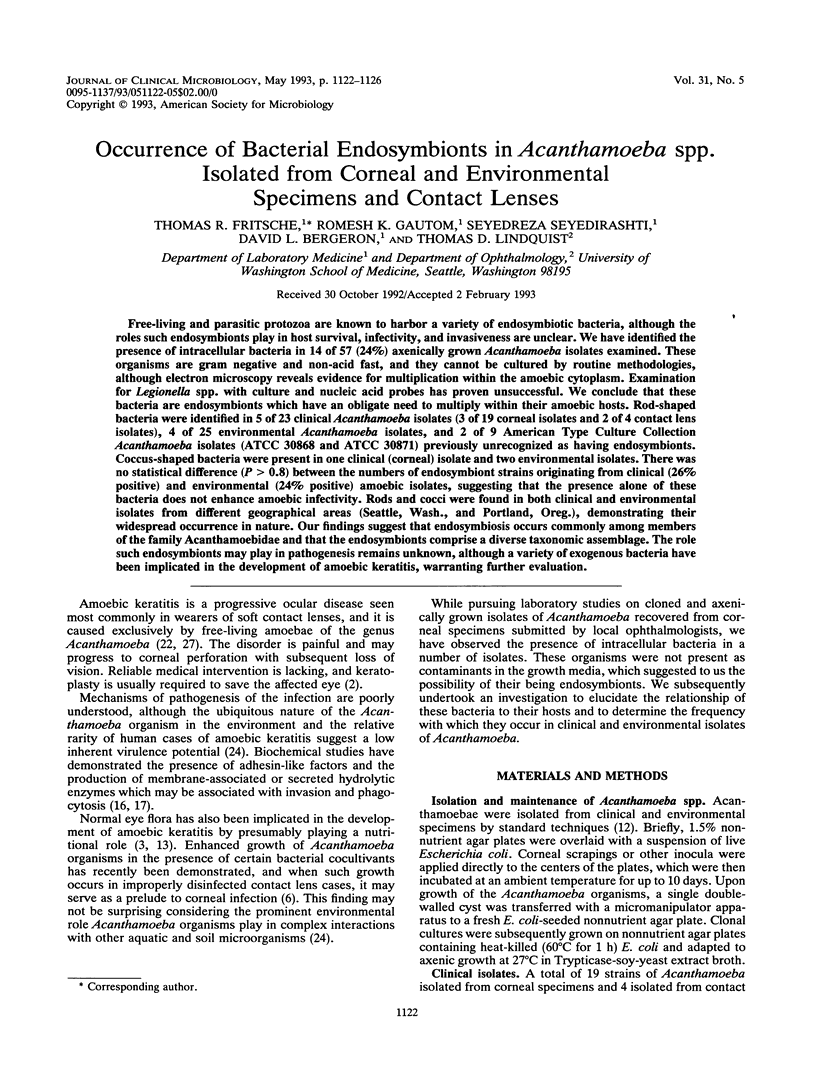

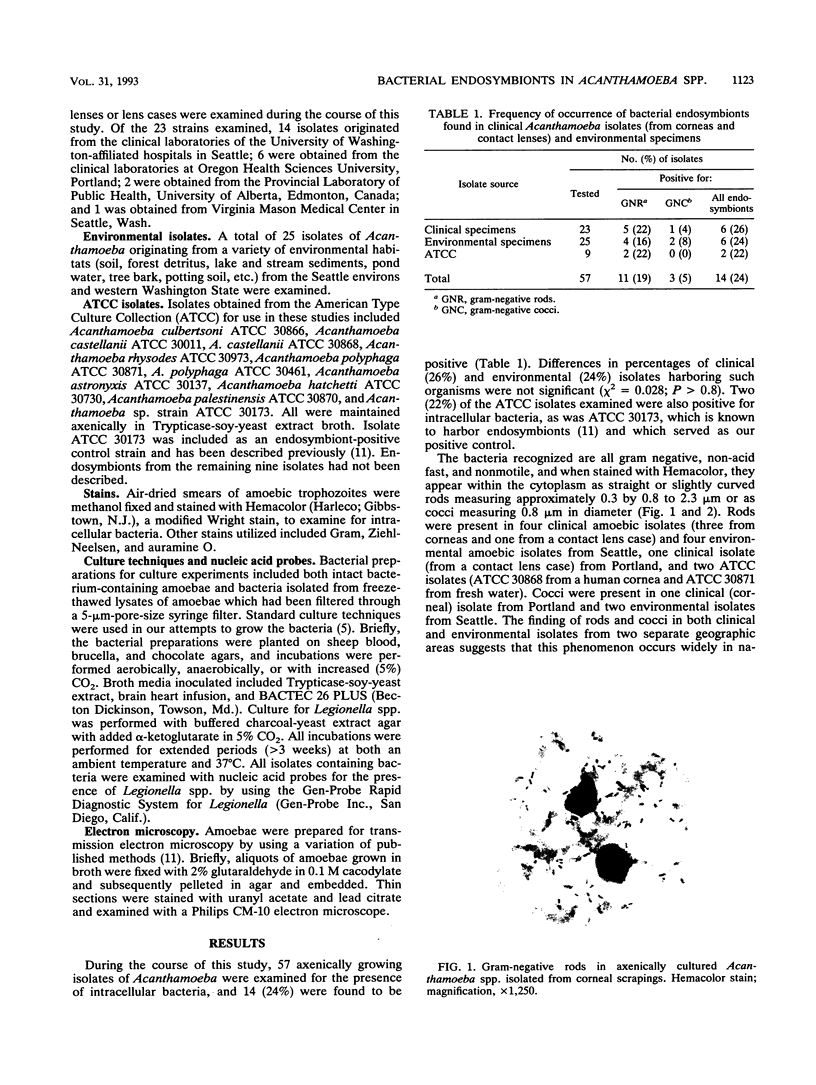

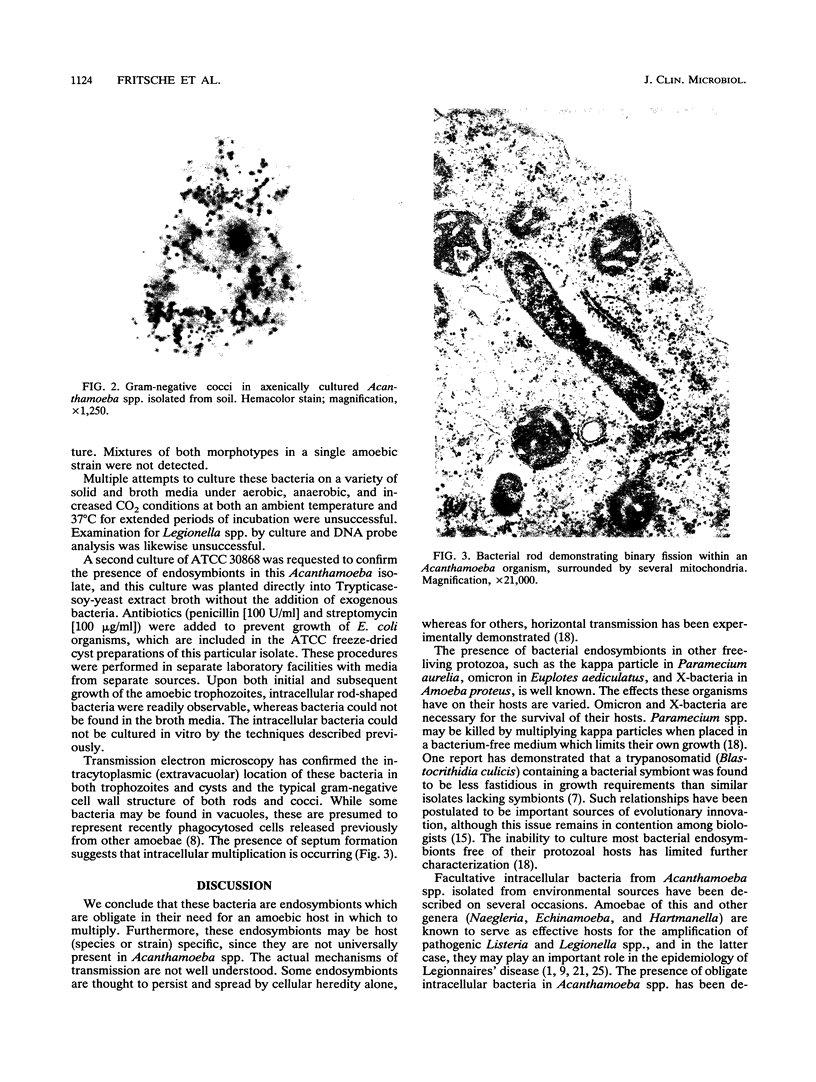

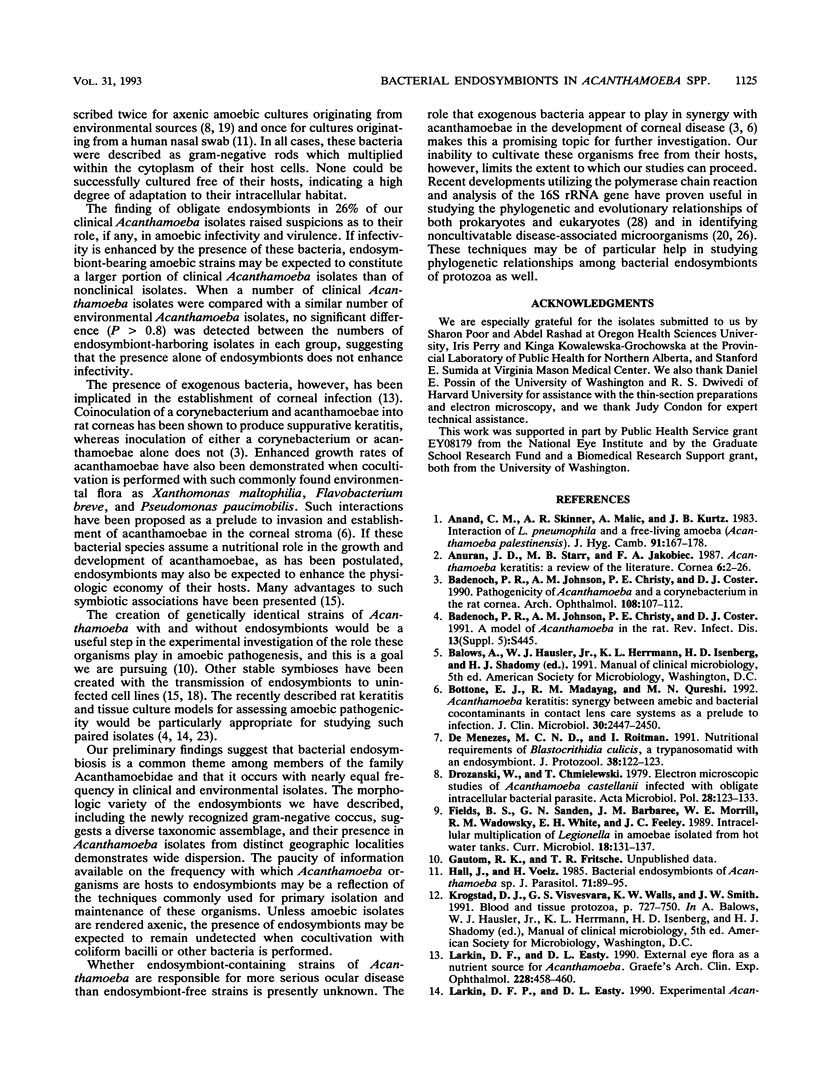

Free-living and parasitic protozoa are known to harbor a variety of endosymbiotic bacteria, although the roles such endosymbionts play in host survival, infectivity, and invasiveness are unclear. We have identified the presence of intracellular bacteria in 14 of 57 (24%) axenically grown Acanthamoeba isolates examined. These organisms are gram negative and non-acid fast, and they cannot be cultured by routine methodologies, although electron microscopy reveals evidence for multiplication within the amoebic cytoplasm. Examination for Legionella spp. with culture and nucleic acid probes has proven unsuccessful. We conclude that these bacteria are endosymbionts which have an obligate need to multiply within their amoebic hosts. Rod-shaped bacteria were identified in 5 of 23 clinical Acanthamoeba isolates (3 of 19 corneal isolates and 2 of 4 contact lens isolates), 4 of 25 environmental Acanthamoeba isolates, and 2 of 9 American Type Culture Collection Acanthamoeba isolates (ATCC 30868 and ATCC 30871) previously unrecognized as having endosymbionts. Coccus-shaped bacteria were present in one clinical (corneal) isolate and two environmental isolates. There was no statistical difference (P > 0.8) between the numbers of endosymbiont strains originating from clinical (26% positive) and environmental (24% positive) amoebic isolates, suggesting that the presence alone of these bacteria does not enhance amoebic infectivity. Rods and cocci were found in both clinical and environmental isolates from different geographical areas (Seattle, Wash., and Portland, Oreg.), demonstrating their widespread occurrence in nature. Our findings suggest that endosymbiosis occurs commonly among members of the family Acanthamoebidae and that the endosymbionts comprise a diverse taxonomic assemblage. The role such endosymbionts may play in pathogenesis remains unknown, although a variety of exogenous bacteria have been implicated in the development of amoebic keratitis, warranting further evaluation.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anand C. M., Skinner A. R., Malic A., Kurtz J. B. Interaction of L. pneumophilia and a free living amoeba (Acanthamoeba palestinensis). J Hyg (Lond) 1983 Oct;91(2):167–178. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400060174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auran J. D., Starr M. B., Jakobiec F. A. Acanthamoeba keratitis. A review of the literature. Cornea. 1987;6(1):2–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenoch P. R., Johnson A. M., Christy P. E., Coster D. J. A model of Acanthamoeba keratitis in the rat. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Mar-Apr;13 (Suppl 5):S445–S445. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.supplement_5.s445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenoch P. R., Johnson A. M., Christy P. E., Coster D. J. Pathogenicity of Acanthamoeba and a Corynebacterium in the rat cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990 Jan;108(1):107–112. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070030113040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottone E. J., Madayag R. M., Qureshi M. N. Acanthamoeba keratitis: synergy between amebic and bacterial cocontaminants in contact lens care systems as a prelude to infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1992 Sep;30(9):2447–2450. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2447-2450.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozanski W., Chmielewski T. Electron microscopic studies of Acanthamoeba castellanii infected with obligate intracellular bacterial parasite. Acta Microbiol Pol. 1979;28(2):123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J., Voelz H. Bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba sp. J Parasitol. 1985 Feb;71(1):89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin D. F., Easty D. L. External eye flora as a nutrient source for Acanthamoeba. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1990;228(5):458–460. doi: 10.1007/BF00927262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton L. D., McLaughlin G. L., Whiteley H. E. Effects of temperature, amebic strain, and carbohydrates on Acanthamoeba adherence to corneal epithelium in vitro. Infect Immun. 1991 Oct;59(10):3819–3822. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3819-3822.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrin J. L., Ortega-Barria E., Barza M., Baum J., Pereira M. E. Neuraminidase activity in acanthamoeba species trophozoites and cysts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Nov;32(12):3061–3066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proca-Ciobanu M., Lupascu G. H., Petrovici A. l., Ionescu M. D. Electron microscopic study of a pathogenic Acanthamoeba castellani strain: the presence of bacterial endosymbionts. Int J Parasitol. 1975 Feb;5(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(75)90097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relman D. A., Loutit J. S., Schmidt T. M., Falkow S., Tompkins L. S. The agent of bacillary angiomatosis. An approach to the identification of uncultured pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1990 Dec 6;323(23):1573–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowbotham T. J. Current views on the relationships between amoebae, legionellae and man. Isr J Med Sci. 1986 Sep;22(9):678–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehr-Green J. K., Bailey T. M., Visvesvara G. S. The epidemiology of Acanthamoeba keratitis in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989 Apr 15;107(4):331–336. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopak S. S., Roat M. I., Nauheim R. C., Turgeon P. W., Sossi G., Kowalski R. P., Thoft R. A. Growth of acanthamoeba on human corneal epithelial cells and keratocytes in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Feb;32(2):354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadowsky R. M., Butler L. J., Cook M. K., Verma S. M., Paul M. A., Fields B. S., Keleti G., Sykora J. L., Yee R. B. Growth-supporting activity for Legionella pneumophila in tap water cultures and implication of hartmannellid amoebae as growth factors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988 Nov;54(11):2677–2682. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.11.2677-2682.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg W. G., Barns S. M., Pelletier D. A., Lane D. J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991 Jan;173(2):697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmus K. R. Introduction: the increasing importance of Acanthamoeba. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Mar-Apr;13 (Suppl 5):S367–S368. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.supplement_5.s367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese C. R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987 Jun;51(2):221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]