ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Buprenorphine can be used for the treatment of opioid dependence in primary care settings. National guidelines recommend directly observed initial dosing followed by multiple in-clinic visits during the induction week. We offered buprenorphine treatment at a public hospital primary care clinic using a home, unobserved induction protocol.

METHODS

Participants were opioid-dependent adults eligible for office-based buprenorphine treatment. The initial physician visit included assessment, education, induction telephone support instructions, an illustrated home induction pamphlet, and a 1-week buprenorphine/naloxone prescription. Patients initiated dosing off-site at a later time. Follow-up with urine toxicology testing occurred at day 7 and thereafter at varying intervals. Primary outcomes were treatment status at week 1 and induction-related events: severe precipitated withdrawal, other buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal symptoms, prolonged unrelieved withdrawal, and serious adverse events (SAEs).

RESULTS

Patients (N = 103) were predominantly heroin users (68%), but also prescription opioid misusers (18%) and methadone maintenance patients (14%). At the end of week 1, 73% were retained, 17% provided induction data but did not return to the clinic, and 11% were lost to follow-up with no induction data available. No cases of severe precipitated withdrawal and no SAEs were observed. Five cases (5%) of mild-to-moderate buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal and eight cases of prolonged unrelieved withdrawal symptoms (8% overall, 21% of methadone-to-buprenorphine inductions) were reported. Buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal and prolonged unrelieved withdrawal symptoms were not associated with treatment status at week 1.

CONCLUSIONS

Home buprenorphine induction was feasible and appeared safe. Induction complications occurred at expected rates and were not associated with short-term treatment drop-out.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0866-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

INTRODUCTION

Buprenorphine, a partial µ opioid receptor agonist, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2002 for office-based opioid dependence pharmacotherapy.1 Buprenorphine’s favorable safety profile and limited diversion potential allow it to be prescribed by certified physicians outside of the highly regulated and often stigmatized settings of dedicated substance abuse treatment programs, including methadone maintenance. Rates of opioid abstinence and treatment retention are comparable for buprenorphine and moderate-dose methadone.2–4 Despite its promise, prescriptions for buprenorphine have lagged behind the growing need for opioid dependence treatment fueled in recent years by the rise of prescription opioid misuse and the continued out-of-treatment status of most heroin users.5–7 Slow adoption of buprenorphine by generalist physicians may relate to the mandated certification training, reimbursement concerns, and, particularly for addiction treatment novices, the perceived difficulty of the induction process.8–11

Directly observed buprenorphine induction dosing of patients in opioid withdrawal is an important element of national treatment guidelines.1,12–14 Buprenorphine has higher µ opioid receptor binding affinity than other opioids, yet, as a partial µ agonist, may precipitate acute opioid withdrawal symptoms in tolerant patients who have recently used opioids. Patients must refrain from use and enter a state of opioid withdrawal prior to buprenorphine induction. Guidelines recommend that clinicians document withdrawal symptoms prior to induction dosing and then monitor patients over a 1-2-h period. At least one follow-up visit during week 1 is encouraged.1

The guidelines intend to minimize induction complications and ensure a smooth transition onto buprenorphine. Observed induction, however, presents significant challenges to many practices. Staffing, regulations restricting in-clinic dispensing of controlled substances, and waiting area logistics may not readily accommodate patients in active opioid withdrawal being given buprenorphine and subsequent assessments over several hours in clinic.

An alternative to this paradigm is off-site, ‘home,’ or unobserved induction. In this model, a patient is evaluated prior to beginning treatment, typically while still using opioids and not in withdrawal. If eligible, the patient then receives a buprenorphine prescription, decides when to discontinue opioid misuse and initiate withdrawal, and self-administers the first dose of buprenorphine unobserved. This sequence is consistent with most ambulatory prescribing. It offers potential time-saving advantages, provided the induction experience is otherwise as safe and uncomplicated as observed induction. Recent descriptions of these two approaches in two Boston practices revealed no differences between groups in longitudinal outcomes.15,16 A 2007 Massachusetts survey indicated that many physicians (42%) had adopted home induction as regular practice.8

There is little published data specifically examining the feasibility of and early outcomes associated with initiating buprenorphine at home, including rates of precipitated withdrawal, other adverse events, and treatment retention during week 1. This study presents data from the Bellevue Hospital Center’s Adult Primary Care Clinic, which since 2006 has prescribed only home buprenorphine induction to all patients beginning office-based treatment.

METHODS

Eligible patients were adults with current DSM-IV opioid dependence seeking buprenorphine treatment and agreeing to a goal of opioid abstinence seen from August 2006 through January 2008. Patients with disabling medical or psychiatric conditions deemed unsafe for office-based treatment, pregnant women eligible for methadone treatment, and persons on methadone >40 mg daily were ineligible. Co-occurring substance misuse (benzodiazepines, alcohol, cocaine) did not exclude participation.

Referral sources included hospital clinics and inpatient units, New York City (NYC) jails, area addiction programs, internet locators, and word of mouth. Participants were encouraged to present for induction with active Medicaid or other insurance that covered buprenorphine prescriptions, but were seen regardless of insurance status or ability to pay. The program did not have funding to provide buprenorphine medication to new patients. Three buprenorphine-certified general internists (JL, EG, MG), two of whom are certified by the American Society of Addiction Medicine in addiction medicine (JL, MG), staffed a weekly half-day buprenorphine clinic. An MPH-level clinic coordinator (DD) assisted with referrals and scheduling, telephone support, and data collection. Extramural funds from the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation provided partial support for staff effort and development of a patient education pamphlet. The New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved observational data collection.

Initial Visit The initial visit included medical, psychiatric, and substance use assessments within a standard 30-45-min new patient appointment. DSM-IV opioid dependence was documented by history. Transaminase levels, hepatitis serologies, and HIV testing were performed if indicated. Patients provided urine for later laboratory toxicology assays; in-clinic urine dip tests were not used. An initial 4-mg buprenorphine dose followed by one to two additional 4-mg doses, as needed every 1-4 h, for a day 1 maximum of 12 mg, was recommended to all patients. (References to doses denote milligrams of buprenorphine: in practice, buprenorphine/naloxone in a 4:1 ratio was prescribed, the formulation marketed as Suboxone). Subsequent 4-mg incremental adjustments from day 2 on established a maintenance dose. A bilingual pictogram-based patient education pamphlet summarized induction dosing and emphasized being in opioid withdrawal at the time of induction (Online Appendix). Before the conclusion of the visit, patients ”taught-back” how they would initiate induction.17 Patients were instructed to telephone the prescribing physician or clinic coordinator during day 1-3 of induction and to return for follow-up at week 1 (day 7). A 7-day prescription, typically 14 8-mg/2-mg buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone) tablets, was issued. Patients filled prescriptions at their preferred community pharmacy.

Follow-up Visits Physicians assessed on-going drug use, adverse medication effects, and treatment response within a standard 20-min revisit appointment. Urine toxicologies were collected each visit; results were available within 1-2 days, and results from the last visit were discussed at the current visit. Referrals for psychiatric care and/or additional addiction counseling were made as indicated. Physicians provided other primary care, but usually focused visits on opioid treatment. Follow-up visits after week 1 occurred at varying intervals as determined by the physician, with patients typically seen every 1-4 weeks during the first few months and at 4-8-week intervals thereafter. Continued opioid use prompted increased visit frequencies, targeted counseling, and often dose adjustment. Physicians pursued a policy of referring patients to alternative care including intensive outpatient and methadone maintenance if patients were unable to keep regularly scheduled appointments, or if uncontrolled opioid or other drug use prevented effective or safe treatment.

Data Collection Baseline and follow-up data were collected systematically by the physician or coordinator. Baseline data included self-reported opioid and other drug use, general health history, and demographics. Follow-up data included self-report of induction-associated adverse events, drug use, buprenorphine dosing, and other treatment involvement. Standard electronic medical record (EMR) progress notes completed at each visit synthesized interview data as well as pertinent information from referral sources or the patient’s record. If patients were not in contact by telephone or in person by week 1 (day 7), staff attempted contact. For a consecutive subset of 17 patients, we maintained a record of the time and duration of all telephone contacts. Urine was tested for opiates, methadone, cocaine, benzodiazepines, and cannabis. Testing for specific synthetic opioids (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, fentanyl, buprenorphine) was not available.

Analysis Primary outcomes were those potentially related to the home induction protocol: induction events and treatment retention at week 1. Patient-reported events were classified in four distinct categories: (1) severe precipitated withdrawal, defined as any sudden onset or worsening of opioid withdrawal symptoms characterized as severe and following the initial dose of buprenorphine; (2) serious adverse events (SAEs), defined as death, a life-threatening or other event necessitating emergency medical treatment, or hospitalization or causing persistent or significant disability or incapacity; (3) buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal symptoms, defined by the investigators as any new or worsening opioid withdrawal symptoms (i.e., anxiety, sweating, pain, nausea) not present or worsening with the initial doses of buprenorphine and characterized as mild or moderate; (4) prolonged unrelieved withdrawal, defined by investigators as opioid withdrawal symptoms that persisted until or past day 2 of treatment.18,19 The investigators used surveys, progress notes, and subsequent interviews with patients not retained and without week 1 contact to ascertain the presence or absence of induction events. Secondary outcomes were: duration of treatment (defined as the period from induction through the last week of the last active buprenorphine prescription), maintenance dose, self-reported heroin and other opioid use, and urine toxicology results.

Baseline characteristics and rates of induction complications and week 1 retention were estimated using descriptive statistics (proportions, means, ranges). Bivariate logistic regression yielding crude odds ratios explored patient characteristics and induction complications associated with week 1 retention. Longitudinal treatment retention was analyzed as a continuous variable. A Kaplan-Meier survival function displayed retention through week 24 for all subjects. Urine opiate and methadone toxicology data were summarized as means of individual patients’ proportion of total urines testing positive for opiates or methadone during consecutive 4-week intervals. Self-reported opioid use was dichotomized as any use during consecutive 4-week intervals. Analysis was performed using Stata IC/10.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

One hundred three patients were offered buprenorphine induction from August 2006 to January 2008. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. Patients were predominantly male and racial/ethnic minorities. Most had Medicaid or were uninsured. Sixty-eight percent were current heroin users, 18% were dependent on prescription opioids, and 14% were on methadone maintenance at 40 mg daily or less. Half reported previous use of buprenorphine. Four additional patients presenting for treatment were ineligible: three on high methadone maintenance doses (>40 mg) and one with untreated psychiatric symptoms.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants: Home Buprenorphine Induction (N = 103)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 85 (82) |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 42 (25-60) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American | 11 (11) |

| Hispanic | 41 (40) |

| White | 42 (41) |

| Other | 9 (9) |

| Insurance status | |

| Medicaid | 67 (65) |

| Private insurance | 21 (20) |

| No insurance | 15 (15) |

| Unemployed | 80 (78) |

| Homeless* | 6 (6) |

| Referred from jail or current parole or probation | 26 (25) |

| Referral source | |

| Other substance use providers or programs | 33 (32) |

| Word of mouth | 25 (24) |

| New York City jails | 13 (13) |

| Inpatient detoxification | 7 (7) |

| Internet locators | 4 ((4) |

| Other or unknown referral source | 21 (20) |

| Substance use history | |

| Heroin use, previous 7 days | 70 (68) |

| Prescription opioid misuse, previous 7 days† | 21 (20) |

| Methadone maintenance treatment, current | 14 (14) |

| Injection drug use (IDU), previous 7 days | 33 (32) |

| Any daily heroin use, lifetime | 99 (96) |

| Cocaine use, previous 7 days | 31 (30) |

| Benzodiazepine use, previous 7 days | 24 (23) |

| Heavy alcohol use (>5 drinks/occasion), previous 7 days | 19 (18) |

| Smoking, current | 84 (82) |

| Substance use treatment history | |

| Buprenorphine treatment, ever | 44 (43) |

| Buprenorphine, informal (‘street’) use, ever | 7 (7) |

| Methadone maintenance treatment, ever | 74 (72) |

| Outpatient addiction treatment, previous 7 days | 26 (25) |

| AA, NA, other mutual help, previous 7 days | 25 (24) |

| Psychiatric history, self-report | |

| Mental health disorder (other than substance use), lifetime | 37 (36) |

| Major depression or anxiety disorder, lifetime | 16 (16) |

| Bipolar disorder, lifetime | 5 (5) |

| Schizophrenia or psychotic disorder, lifetime | 1 (1) |

| Any psychiatric treatment, current | 22 (21) |

| Medical history | |

| Any chronic medical problem, lifetime | 50 (49) |

| Hepatitis C‡ | 35 (34) |

| HIV‡ | 4 (4) |

| Chronic pain condition, current | 14 (14) |

*Homelessness was defined as no stable housing or shelter residence reported in the week prior to baseline

†Two predominantly heroin-using patients had also used prescription opioids in the last 7 days prior to the induction visit

‡HCV and HIV status is by laboratory testing or self-report; baseline laboratory testing was not completed in all patients

Self-reported data regarding the home induction process were available for 92 (89%) participants: 75 (73%) who returned for a scheduled week 1 (day 7) visit, and 17 (17%) who did not return at week 1, but communicated with staff. The remaining 11 (11%) patients had no contact following their induction visit (Table 2). The mean induction day 1 total buprenorphine dose was 12 mg (4-32 mg) with 12% exceeding the recommended 12 mg maximum. No patients reported difficulty with sublingual dosing. Buprenorphine/naloxone was used for induction in all but two patients who requested and received buprenorphine monotherapy (Subutex).

Table 2.

Week 1 Follow-Up Status and Self-Reported Induction Events Following Home Buprenorphine Induction

| Status at week 1 (N = 103) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Follow-up visit at week 1 (day 7) complete | 75 (73) |

| No follow-up visit at week 1, induction data available | 17 (17) |

| No follow-up visit at week 1, no further contact | 11 (11) |

| Self-reported induction events (n = 92) | n (%) |

| Severe precipitated withdrawal* | 0 (0) |

| Serious adverse events† | 0 (0) |

| Buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal‡ | 5 (5) |

| Nausea | 1 (1) |

| Anxiety/irritability | 1 (1) |

| Sweating | 1 (1) |

| Musculoskeletal pain/aches | 1 (1) |

| Sleepiness/sedation | 2 (2) |

| Prolonged unrelieved withdrawal§ | 5 (5) |

| Did not fill induction prescription | 4 (4) |

| Day 1 total dose exceeded recommended 12 mg | 11 (12) |

| Day 1 dose, mean (range) | 12 mg (4-32) |

*Severe precipitated withdrawal was defined as any sudden onset or significant worsening of opioid withdrawal symptoms characterized as severe and following the initial dosing of buprenorphine/naloxone during induction day 1

†Serious adverse events included death, a life-threatening or severe adverse event necessitating emergency medical treatment or hospitalization (i.e., trauma, seizure, pneumonia, psychosis) or new-onset persistent or significant disability/incapacity

‡Buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal symptoms were defined as any new or worsening opioid withdrawal symptoms characterized by patients as mild or moderate (vs. severe) following the initial doses of buprenorphine/naloxone during day 1

§Prolonged unrelieved withdrawal symptoms were defined as persistence of opioid withdrawal symptoms for more than 1 day after the initial dose of buprenorphine/naloxone

Of the 92 participants with data on the induction experience, none described rapid onset, dramatic worsening of withdrawal symptoms consistent with severe precipitated withdrawal, and no SAEs were reported or observed (Table 2). Five patients reported likely buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, nausea without vomiting, sweating, musculoskeletal aches, and sleepiness/sedation. These symptoms were described as mild or moderate, relieved by further buprenorphine/naloxone doses, and resolved by induction day 3. All patients with this category of symptoms returned for week 1 follow-up and continued on buprenorphine. An additional five patients experienced prolonged unrelieved withdrawal symptoms: 2 cases among 91 (2%) heroin- or prescription opioid-using patients, and 3 among the 14 (21%) methadone-to-buprenorphine inductions. These symptoms included irritability/anxiety, musculoskeletal pain, and gastrointestinal upset not relieved by initial buprenorphine dosing and lasting several days. Three of these five patients (one heroin, two methadone maintenance) did not return for follow-up at week 1. Of the 17 patients who did not have a week 1 visit but were in communication with staff, four reported never filling the initial buprenorphine prescription.

Telephone support of induction was tracked in a convenience sub-sample of 17 consecutive patients: 3 (18%) patients called physicians or the coordinator as instructed on induction days 1-3, 4 (24%) contacted staff on days 4-6, 4 (24%) who had not contacted staff either answered a staff call or returned a message during days 4-6, and 6 (35%) remained out of contact during week 1 following multiple staff calls. Phone contacts averaged 3-4 min and generally involved reports by patients of their induction experience. No patients were instructed to alter their prescribed treatment regimen, seek emergency care, or return to the clinic prior to the scheduled week 1 visit. These 17 participants resembled the total sample in terms of ethnicity, predominant heroin use, and insurance status.

Bivariate logistic regression was used to examine associations of patient characteristics with week 1 treatment retention. A history of any previous buprenorphine use (either formal treatment or informal ‘street’ use) was associated with week 1 treatment retention (OR 4.4, 95% CI 1.7-12), while reporting prolonged or buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal during induction was not (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline and Induction-Related Factors Associated with Treatment Retention at Week 1 (Day 7)

| Week 1 follow-up visit (N = 75) | No week 1 follow-up visit (N = 28) | Odds ratio* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) |

| Heroin use, previous 7 days | 47 (63) | 23 (82) | 0.3 (0.1-1.1) |

| Injection use, previous 7 days | 21 (28) | 13 (46) | 0.5 (0.2-1.1) |

| Outpatient drug or alcohol treatment, previous 7 days | 20 (27) | 5 (18) | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) |

| Cocaine use, previous 7 days | 17 (23) | 7 (25) | 1.1 (0.4-2.9) |

| Mental health disorder, lifetime | 29 (39) | 8 (29) | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) |

| Benzodiazepine use, previous 7 days | 9 (12) | 3 (11) | 1.5 (0.3-6.5) |

| Chronic pain condition | 9 (12) | 2 (7) | 1.8 (0.4-8.8) |

| Previous buprenorphine use, any | 44 (59) | 7 (25) | 4.4 (1.7-12) |

| Week 1 follow-up visit (N = 75) | No week 1 follow-up visit (N = 17)† | Odds OR | |

| Self-reported induction events | n (%) | n (%) | (95% CI) |

| Severe precipitated withdrawal | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Na |

| Serious adverse events | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Na |

| Buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | na‡ |

| Prolonged unrelieved withdrawal | 4 (5) | 3 (18) | 0.3 (0.1-1.3) |

| Did not fill induction prescription | 0 (0) | 4 (24) | 0 (0)§ |

| Day 1 total dose exceeded recommended 12 mg | 9 (12) | 1 (6) | 1.2 (0.1-11) |

*Odds ratios compare the frequency of week 1 follow-up among people with versus without each baseline characteristic

†Data available for 17 of 28 patients with no follow-up at week 1

‡Reporting buprenorphine-prompted withdrawal symptoms was perfectly associated with follow-up visit at week 1

§Reporting not filling the induction prescription was perfectly inversely associated with follow-up visit at week 1

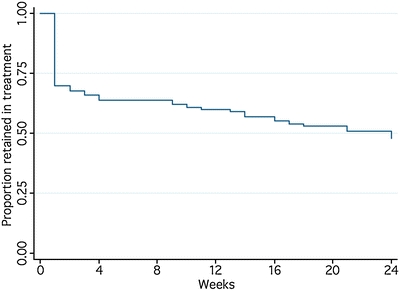

Treatment retention was 59% at week 12 and 50% at week 24 (Fig. 1). Overall retention to date was 29 weeks (1-117 weeks); among patients active in treatment at analysis (N = 29), retention was 68 weeks (37-117 weeks); among inactive patients (N = 74), retention (time to drop-out) was 14 weeks (1-69 weeks).

Figure 1.

Treatment retention following home buprenorphine induction (N = 103).

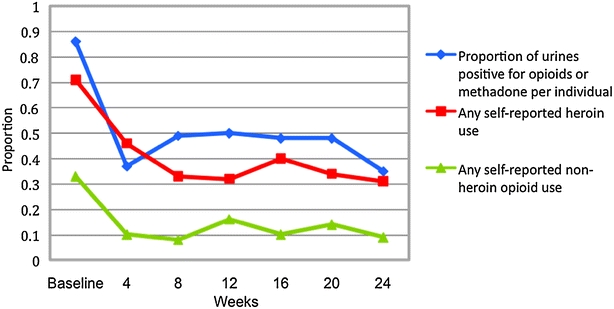

The mean daily buprenorphine maintenance dose among all patients retained past week 1 (N = 75) was 17 mg (2-32 mg; median 16 mg). Urine toxicology and self-report data indicated ongoing opioid use in a substantial proportion of patients (Fig. 2). Among patients in treatment at 24 weeks, 24% of individuals had no positive urines for opiates or methadone throughout, 52% were intermittently positive, and 24% were positive throughout. Self-reported opioid use declined from a mean of 7 days per week at baseline to 1 day per week (range 0-7) at week 12.

Figure 2.

Urine toxicology results for opiates and methadone and self-reported heroin and other opioid use following home buprenorphine induction. *Urine toxicology results display the group mean for individual subjects’ proportion of urines positive for opiates or methadone within 4-week intervals. Results at week 4 exclude baseline urine results. †Heroin use data indicate the proportion of patients reporting any heroin use within the 4-week intervals. ‡Other opioid use data indicate the proportion of patients reporting any other (non-heroin) opioid use within the 4-week intervals.

DISCUSSION

Initiating buprenorphine treatment using a home induction protocol was feasible among predominantly heroin-using, Medicaid-insured patients in an urban public hospital primary care setting. Following an initial physician visit and provision of an induction patient pamphlet and written buprenorphine/naloxone prescription, rates of buprenorphine-prompted and prolonged unrelieved opioid withdrawal symptoms were low (5%), and no cases of severe precipitated withdrawal or SAEs were recorded among the 89% of patients with week 1 induction data available. These findings are consistent with national buprenorphine safety data and the low rates of directly observed induction complications from earlier clinical trials.5,20,21 Our data suggest that opioid-dependent persons coached on the buprenorphine induction process can successfully begin the medication outside of the clinic.

Twenty-eight (27%) patients did not return for week 1 follow-up. This drop-out rate is similar to that in a comparable primary care-based study, in which 17 of 52 (33%) patients in Rhode Island offered directly observed induction either did not appear for induction (21%) or did not return immediately post-induction (12%).22 It is higher than the 6% day 1-3 drop-out rate among self-pay patients in a North Carolina private practice setting, and lower than the 41% (29 of 70) of patients eligible for buprenorphine who never completed an initial assessment or did not return for observed induction at a Bronx, NY, community health center.23,24 Clearly some attrition can be expected as patients plan for and then begin buprenorphine treatment. If home induction results in higher immediate drop-out or more induction complications, this would offset any resource-sparing advantages gained by combining the initial assessment and induction prescription into a single visit. Formal comparison of the outcomes associated with a single vs. multiple induction-related visits with or without telephone support is needed.

Patient feedback was positive regarding the home induction patient education pamphlet designed for persons with low health literacy. Patients reported referring repeatedly to the pamphlet during home induction. Telephone support, in contrast, was used infrequently in a sub-sample of 17 patients whose phone utilization was tracked formally. Low perceived need for telephone support likely reflected use of the induction pamphlet, low rates of complications, and many patients’ prior experience taking buprenorphine.

Of the 11 participants lost to contact at week 1, all had either positive baseline urines for opiates/methadone or referral information corroborating active opioid dependence. It is unlikely they were offered treatment inappropriately. Unanticipated difficulties with Medicaid prescription benefits were common, including four patients who reported being unable to fill their induction prescriptions and not returning at week 1. Though ambivalence toward treatment and malingering or diversion cannot be excluded, logistic difficulties (Medicaid problems, commuting and work schedule conflicts) appeared to account for much of the week 1 drop-out. Confirming prescription drug insurance benefits prior to induction may be worthwhile.

Prolonged spontaneous opioid withdrawal was observed at higher rates during methadone-to-buprenorphine inductions (21%) than among inductions of heroin and prescription opioid users (2%). Alerting low-dose methadone patients to the potential discomforts of prolonged withdrawal symptoms upon transfer to buprenorphine is important. Also noted, 12% of patients reported exceeding the maximum recommended day 1 dose of 12 mg buprenorphine. Higher (>12 mg) day 1 doses may well be safe and effective if withdrawal symptoms persist, given buprenorphine’s µ opioid agonist ceiling and limited potential for CNS and respiratory depression.25,26

Rates of treatment retention at 24 weeks (50%) were similar to those in diverse settings and to national practice trends,5,22,27,28 and are noteworthy among a mostly heroin-using sample with 78% unemployment and high rates of criminal justice involvement. Self-reported opioid use declined markedly over 24 weeks. As ‘best practices’ pertaining to primary care-based buprenorphine treatment evolve, strategies that merit additional consideration include improving access to in-clinic individual and group counseling, enhanced nurse involvement, integration with psychiatric services, and contingency management strategies.14,16,22,29,30

Limitations included no directly observed induction, preventing comparisons with home induction. Extramural support and a clinic coordinator, participation by physicians certified in addiction medicine, moderate rates of previous exposure to buprenorphine, and patients recruited from outside the existing primary care population may limit generalizabilty. Our inability to store and dispense buprenorphine does not apply elsewhere. Point-of-care drug testing and assays for synthetic opioids including oxycodone and buprenorphine were not used. Continued synthetic opioid misuse or buprenorphine noncompliance may have occurred undetected. Finally, analysis of week 1 treatment retention was not powered to adequately estimate all associations, and no patient satisfaction data were collected to potentially explain drop-out or longitudinal opioid use.

We found that a home buprenorphine induction protocol was simple to implement and sustain, and resulted in no observed SAEs, few reported induction complications, and treatment retention rates consistent with previous studies. Further research comparing buprenorphine induction approaches and defining optimal primary care treatment models could increase use of this effective treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

“Burpenorphine – Beginning Treatment” (please see attached PDF) (PDF 544 KB)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Andrew B. Wallach and Valerie D. Perel and the staff of the Bellevue Adult Primary Care Clinic, and Drs. Stephen Ross, John Rotrosen, Sapana Shah and Andrea Truncali for their advice and support. Funding: This study was supported in part by a grant from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed. Drs. Lee and Gourevitch receive research funding from Cephalon, Inc., and Alkermes, Inc., to support studies of alcohol treatment.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0866-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction: A Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004. [PubMed]

- 2.Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE. Comparison of buprenorphine and methadone in the treatment of opiate dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;151(7):1025–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Johnson RE, Chutuape MA, Strain EC, Walsh SL, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine and methadone for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(18):1290–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mattick R, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(2):CD002207. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. SAMHSA Evaluation of the Impact of the DATA Waiver Program. http://buprenorphine.samsha.gov/, accessed May 12, 2008.

- 6.Kuehn B. Office-based treatment of opioid addiction achieving goals. JAMA. 2005;294(7):784–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Walley AY, Alperen JK, Cheng DM, et al. Office-based management of opioid dependence with buprenorphine: clinical practices and barriers. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1393–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Cunningham CO, Kunins HV, Roose RJ, Elam RT, Sohler NL. Barriers to obtaining waivers to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid addiction treatment among HIV physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1325–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Kissin W, McLeod C, Sonnefeld J, Stanton A. Experiences of a national sample of qualified addiction specialists who have and have not prescribed buprenorphine for opioid dependence. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(4):91–103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Netherland J, Botsko M, Egan J, et al. Factors affecting willingness to provide buprenorphine treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. In Press, available online 20 Aug 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry. Buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence. http://training.aaap.org/, accessed Nov. 14, 2008.

- 13.American Society of Addiction Medicine, Clinical Tools, Inc. Online buprenorphine training. http://buprenorphineCME.com, accessed Nov. 14, 2008.

- 14.Fiellin DA, Kleber H, Trumble-Hejduk JG, McLellan AT, Kosten TR. Consensus statement on office-based treatment of opioid dependence using buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27(2):153–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mintzer IL, Eisenberg M, Terra M, MacVane C, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Treating opioid addiction with buprenorphine-naloxone in community-based primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(2):146–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Paasche-Orlow MK, Schillinger D, Greene SM, Wagner EH. How health care systems can begin to address the challenge of limited literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):884–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lange WR, Fudala PJ, Dax EM, Johnson RE. Safety and side-effects of buprenorphine in the clinical management of heroin addiction. Drug Alc Dep. 1990;26(1):19–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Johnson RE, Jaffe JH, Fudala PJ. A controlled trial of buprenorphine for opioid dependence. JAMA. 1992;267(20):2750–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ling W, Charuvastra C, Collins JF, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment of opiate dependence: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Addiction. 1998;93(4):475–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Amass L, Ling W, Freese TE, et al. Bringing buprenorphine-naloxone detoxification to community treatment providers: the NIDA Clinical Trials Network field experience. Am J Addict. 2004;13(S1):S42–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Stein MD, Cioe P, Friedmann PD. Buprenorphine retention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1038–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Finch JW, Kamien JB, Amass L. Two-year experience with buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone) for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence within a private practice setting. J Addict Med. 2007;1(2):104–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Cunningham C, Giovanniello A, Sacajiu G, et al. Buprenorphine treatment in an urban community health center: what to expect. Fam Med. 2008;40(7):500–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Walsh SL, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Acute administration of buprenorphine in humans: partial agonist and blockade effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:361–72. [PubMed]

- 26.Johnson RE, Strain EC, Amass L. Buprenorphine: how to use it right. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2 Suppl):S59–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Magura S, Lee S, Salsitz E, et al. Outcomes of buprenorphine maintenance in office-based practice. J Addict Dis. 2007;26(2):13–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Soyka M, Zingg C, Koler G, Kuefner H. Retention rate and substance use in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy and predictors of outcome: results from a randomized study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(5):641–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Schottenfeld RS, Chawarski MC, Pakes JR, Pantalon MV, Carroll KM, Kosten TR. Methadone versus buprenorphine with contingency management or performance feedback for cocaine and opioid dependence. Am J Psych. 2005;162(2):340–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

“Burpenorphine – Beginning Treatment” (please see attached PDF) (PDF 544 KB)