Abstract

Context

Chest pain is a common symptom in primary care settings, associated with considerable morbidity and health care utilization. Failure to recognize panic disorder as the source of chest pain leads to increased health care costs and inappropriate management.

Objective

To identify characteristics of the chest pain associated with the presence of panic disorder, review the consequences and possible mechanisms of chest pain in panic disorder, and discuss the recognition of panic disorder in patients presenting with chest pain.

Data sources

Potential studies were identified via a computerized search of MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases and review of bibliographies. MeSH headings used included panic disorder with chest pain, panic disorder with coronary disease or cardiovascular disorders or heart disorders, and panic disorder with cholesterol or essential hypertension or tobacco smoking.

Study selection

The diagnosis of panic disorder in eligible studies was based on DSM criteria, and studies must have used objective criteria for coronary artery disease and risk factors. Only case control and cohort studies were included.

Data synthesis

Although numerous chest pain characteristics (believed to be both associated and not associated with coronary artery disease) have been reportedly linked to panic disorder, only nonanginal chest pain is consistently associated with panic disorder (relative risk = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.41 to 2.92).

Conclusion

Chest pain during panic attacks is associated with increased health care utilization, poor quality of life, and phobic avoidance. Because the chest pain during panic attacks may be due to ischemia, the presence of panic attacks may go unrecognized. Ultimately, the diagnosis of panic disorder must be based on DSM criteria. However, once panic disorder is recognized, clinicians must remain open to the possibility of co-occurring coronary artery disease.

Chest pain is a common symptom in the general population, reported by 12% to 16% of people.1,2 The probability of experiencing chest pain increases by 8% to 9% per decade of life after age 30. Most people who have chest pain report at least 2 episodes lasting under 4 hours; 35% seek care for their pain.1

In primary care populations, chest pain is even more prevalent, reported in 7% to 24% of patients3–5; 4.8% of patients are referred, usually to cardiologists.6 The presence of chest pain in primary care patients is associated with poorer functional status, especially in role functioning.5 In addition, chest pain results in substantial use of resources. Not only do 91% of patients report their chest pain to their physician,4 but 83% of those are evaluated at a mean cost of $272 per evaluation. Only 6% of these evaluations lead to an organic diagnosis, which means that the average testing cost per organic diagnosis made is $4354.3 Although cardiac diagnoses are made 8% to 34% of the time, and psychiatric diagnoses are made 6% to 37% of the time,3,7–9 the etiology of the chest pain is often not determined.3 Cardiology and mental health referrals are made 1% to 2% and 6% to 14% of the time, respectively, from practice settings.8,9 Prescribed medications are reported as helpful in 58% of patients,4 but this effectiveness is primarily in those whose chest pain has a recognized organic cause. Overall, 65% of primary care patients with chest pain report improvement with or without treatment.3

Patients with chest pain, whether or not they have cardiac disease, use similar strategies to cope with their pain.10 However, emergency department use is higher among patients without significant coronary disease11; emergency department use is predicted by duration of pain during the episode, the presence of other cardiac symptoms, and family history. In addition to these factors, cardiac distress is also dependent on age, education, and medical burden.12 Even after being informed of a normal coronary angiography, patients with chest pain continue to suffer. Sixty percent continue to have chest pain, 17% are rehospitalized, 45% think exertion is dangerous, and 30% limit their physical activity.13 Although clonidine and prazosin have not been shown to help these patients, a variety of medications have at least some efficacy, including estrogen, doxazosin, enalapril, aminophylline, and imipramine.14

Many of these patients may have a mental disorder. Patients whose chest pain is believed to have a psychosomatic cause express significantly more concern about their pain than do their physicians.7 However, unlike chest pain patients without psychiatric disease, those with psychiatric problems cope more through avoidance and wishful thinking and less through seeking support or problem-focused strategies.10 Anxiety disorders are particularly prevalent among primary care patients with chest pain.5 Patients without cardiac or esophageal disease as the cause of their chest pain have increased rates of panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and somatic anxiety.15

Of these, panic disorder is the best recognized and most studied disorder. The purpose of this article is to combine literature and systematic reviews16 to identify characteristics of the chest pain associated with the presence of panic disorder, review the consequences and possible mechanisms of chest pain in panic disorder, and discuss the recognition of panic disorder in patients presenting with chest pain.

FOR CLINICAL USE

♦ Although panic disorder is associated with nonanginal chest pain among emergency room patients, panic disorder can occur with typical angina.

♦ Although routine screening for panic disorder among demographic and symptomatic subgroups of patients presenting with chest pain has been advocated, the likelihood ratios of these decision tools are inadequate for diagnosis.

♦ Even if panic disorder is recognized, clinicians must remain open to the possibility of co-occurring coronary artery disease.

CHEST PAIN AND PANIC DISORDER

This review extends the results from a systematic review previously reported.16 Briefly, potential studies were identified via a computerized search of MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases and review of bibliographies. MeSH headings used included panic disorder with chest pain, panic disorder with coronary disease or cardiovascular disorders or heart disorders, and panic disorder with cholesterol or essential hypertension or tobacco smoking. The diagnosis of panic disorder in eligible studies was based on DSM criteria, and studies must have used objective criteria for coronary artery disease (CAD) and risk factors. Only case-control and cohort studies were included. Using the same search and selection strategies, new studies were sought.

Chest pain is an integral part of panic disorder. Not only is chest pain part of the definitional criteria for a panic attack, but chest pain is a common symptom in patients with panic disorder, occurring in 78% of self-perceived worst panic attacks.17 Conversely, the prevalence of panic disorder among patients with chest pain is high no matter the setting (Table 1) and is just as prevalent in panic attacks that fail to meet DSM criteria for panic disorder.9,20,24,27 However, the prevalence of chest pain during panic attacks depends on the type of panic attack. For example, chest pain is more common in sudden-onset versus gradual-onset attacks (48% vs. 10%)38 but is less common in minor and spontaneous panic attacks (7% and 17%, respectively) than in situational attacks (47%).39 If chest pain is so common in the panic attack experience, what is the origin of the chest pain, and what are its consequences?

Table 1.

Prevalence of Panic Disorder in Patients With Chest Paina

| Setting | Prevalence of Panic Disorder |

| Family practice | 25%9 |

| Emergency department | 18%–26%18,19 |

| Atypical chest pain | 16%–47%20,21 |

| Referral population | |

| Gastrointestinal laboratory (no coronary artery disease) | 34%22 |

| Cardiology | 38%23 |

| Negative work-up | 27%–37%11,24 |

| For cardiac testing | 47%25 |

| For angiography | 10%26 |

| Cardiology | 9%–57%27–29 |

| Sent for electrocardiogram | 62%23,30 |

| No coronary artery disease | 34%–41%31 |

| With atypical chest pain | 41%–59%28,32 |

| Clinic with nonischemic pain | 22%29 |

| Coronary care unit | 31%33 |

| Other | |

| Minimal/no coronary artery disease | 30%–43%34,35 |

| Noncardiac chest pain | 53%12 |

| Cardiac neurosis | 17%36 |

Reprinted with permission from Katerndahl.16

Possible Mechanisms for a Relationship Between Panic Disorder and Ischemia

Although chest wall activity40 and esophageal abnormalities2 have been proposed as the source of chest pain in panic disorder, the most likely source may be ischemia. Tachycardia (often observed during panic attacks) increases oxygen demand. In addition, psychological stress41,42 and panic attacks43 are known to induce reversible ischemia in cardiac patients. Three possible ischemic mechanisms have been proposed as the cause of chest pain.

Decreased heart rate variability.

First, patients with panic disorder display decreased heart rate variability (HRV).44–47 In addition, compared with controls, patients with panic disorder exhibit higher maximal heart rates, higher heart rates upon standing, and decreased PR intervals,30,48 all of which decrease HRV.49 Both diminished variability and tachycardia can potentially lead to increased oxygen demand and ischemia.31 Decreased HRV has also been linked to sudden death.50 Problems with HRV probably reflect autonomic dysfunction; emotion-triggered autonomic surges may cause myocardial dysfunction51 and chest pain.52 However, the association between panic disorder and HRV loses significance if adjusted for other correlates of HRV and cardiac function.53 In addition, a recent study failed to confirm heart variability as the mechanism for cardiovascular morbidity among coronary heart disease patients with panic disorder.54

Microvascular angina.

A second possible mechanism for ischemia in panic disorder is microvascular angina. Hyperventilation associated with attacks could result in increased contractility, stroke volume, and cardiac output. In addition, increased catecholamines could lead to increased peripheral resistance. Recently, people with panic-like anxiety were found to have increased fibrin turnover, suggesting a pro-coagulant mechanism.55 Coupled with spasm of intramyocardial arterioles, these results could produce microvascular angina and, eventually, cardiomyopathy.56 This mechanism may account for the observation that almost 50% of women with chest pain but no CAD have microvascular dysfunction unrelated to cardiovascular risk factors.57 Furthermore, 40% of patients with microvascular angina have panic attacks. In fact, patients with panic disorder and microvascular angina have similar electrocardiograms, exercise treadmill tests, and left ventricular ejection fractions.58 Although microvascular angina can be associated with ongoing chest pain, it can have an excellent prognosis in terms of mortality.59

Coronary artery disease.

Finally, if ischemia is the source of chest pain in panic disorder, the relationship may support an association between panic disorder and CAD. A study of women undergoing Holter monitoring found an association between panic attacks and both ischemic and nonischemic chest pain.53 Analysis of a large managed care database found an association between diagnoses of panic disorder and coronary heart disease after controlling for covariates (OR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.80 to 1.91).60 The Women's Health Initiative also found an association (hazard ratio = 4.20, 95% CI = 1.76 to 9.99)61; if this association is true, myocardial ischemia could cause panic attacks via increased catecholamines or cerebral carbon dioxide levels secondary to lactate62 or, more likely, panic disorder may promote CAD through its relationship with cardiac risk factors.

Consequences of Chest Pain in Panic Disorder

One reason that people with chest pain associated with panic disorder often seek medical care is the distress that accompanies the pain. Patients with panic disorder are sensitive to physiologic cues.17 As a group, those with panic attacks are more concerned about pain, are more convinced that they have a disease, and are more phobic about disease and death than controls. In addition, they more often use blaming, avoidance, and wishful thinking as coping strategies.63 Those with fear as part of their attacks have more panic symptoms with a more recent onset.64 Panic patients are selectively attentive to heart rate and electrocardiograms.65 The significance is that cardiopulmonary fear is the best predictor of the intensity of the cardiac complaints in patients with noncardiac chest pain.66 Even when panic disorder and CAD coexist, the distress perceived by patients with chest pain is typically due to the panic disorder.67 On the other hand, highly anxious patients with panic disorder exhibit increased muscular activity in the chest wall following carbon dioxide inhalation, which predicts frightening cognitions.40 Thus, it is not surprising that people with chest pain due to panic attacks readily seek care for their pain.

However, patients with chest pain often assume that their pain is due to cardiac disease. This assumption explains why community-based individuals with panic attacks have frequently used cardiologists.68 In fact, 9% of community-dwelling people with panic attacks have seen a cardiologist, 6% when initially seeking care for their panic symptoms.69 In addition, cardiologists previously assessed 9% of psychiatric patients with panic disorder.70 Yet, patients with panic disorder are often more distressed than those with cardiac disease and report poorer vitality, mental health, and role functioning than patients with hypertension; poorer mental health and role functioning than patients with congestive heart failure or after myocardial infarction; and poorer vitality and social functioning than patients after myocardial infarction.71

While health care utilization is affected, recognition of panic disorder in patients presenting with chest pain is critical if serious complications are to be avoided. Not only has the presence of chest pain during panic attacks been linked to the presence and severity of phobic avoidance,72 but the severity of the chest pain has been associated with decreased life satisfaction and quality of life,73 and poor health status.74 In addition, 60% of chest pain patients with recent suicidal ideation who present to emergency departments have panic disorder.75 Patients with panic attacks cite their chest pain or belief that they are having a heart attack as the reason for seeking care 9% of the time.76 Chest pain during panic attacks is linked to increased hospitalization,74 medications,34 and emergency department use,74,77 as well as utilization of personal physicians,77 family practitioners, and psychiatrists.69 Failure to recognize panic disorder in patients presenting with chest pain is associated with increased overall health care utilization,78 increased laboratory testing,78,79 and higher follow-up visit costs9 but fewer mental health referrals.20,78,79 In addition, failure to recognize panic is associated with fewer psychotropic medications prescribed,9,78,79 yet 22% are treated with cardiac medications.9 One year after seeking care for chest pain, patients with panic disorder reported a poorer quality of life and more primary care utilization than those without panic disorder.37 Thus, not only is chest pain, which may be due to ischemia, common during panic attacks, but the chest pain itself and failure to recognize panic are also associated with serious consequences in terms of avoidance, quality of life, and health care utilization. This makes recognition critical.

Recognition of Panic Disorder in Patients With Chest Pain

Panic disorder often goes undiagnosed. In one study, none of the 26% of patients with panic disorder who presented to the emergency department with chest pain were correctly diagnosed.18 A similar study in a family practice setting found that only 4 (15%) of 26 patients with panic attacks were accurately identified, while 2 were diagnosed with CAD. However, twelve (46%) were recognized as having chest pain due to anxiety or stress.9 Because primary care physicians have been shown to be capable of differentiating between panic disorder and cardiac disease,80 failure to recognize panic disorder in patients seeking care for chest pain may be due to the variability of chest pain17,81 or its clustering with other symptoms during panic attacks.81,82 Are there patterns in the chest pain seen in patients with panic disorder that could facilitate recognition?

Characteristics of chest pain associated with panic disorder.

Systematic review found that there were insufficient numbers of homogeneous studies to quantitatively summarize the relationship between most pain characteristics and panic disorder.16 However, 3 studies18,19,74 conducted in emergency departments were sufficiently similar to combine (Table 2). Their combined weighted results showed that the relative risk of panic disorder in patients with nonanginal chest pain (lacking the classical features of substernal chest pain or pressure, brought on by exertion and relieved with rest) is 2.03 (CI = 1.41 to 2.92).16 Panic disorder has frequently been seen in those patients having atypical angina or atypical chest pain.18,20,21,31,34,83–86 However, panic disorder has also been seen in 4% to 65% of patients with typical angina (defined as substernal chest pain or pressure, brought on by exertion and relieved with rest).2,28,32 Further complicating the angina–atypical angina link to panic disorder is the fact that 10% of patients with ischemic chest pain have panic disorder.87 In addition, although frequently described as sharp in nature, non-radiating, and occurring in the left chest, chest pain in patients with mitral valve prolapse (MVP)—a condition associated with panic disorder—is reported as anginal in 10% to 20% of patients.88 Conversely, only 64% of patients with heart disease have chest pain,22 some patients with CAD have atypical chest pain,84 and only 79% of patients with significant CAD have angina.11 In emergency department patients with acute chest pain, angina was most common in those patients with both panic disorder and acute ischemia.19 In addition, some studies have either failed to find an association between panic disorder and angina89 or have found no difference in the prevalence of angina and atypical angina (19%) in patients with panic disorder.87 Hence, although considerable evidence supports the association between atypical angina and panic disorder, typical angina is also reported.

Table 2.

Included Studies Assessing the Relationship Between Nonanginal Pain and Panic Disorder in Patients Presenting to Emergency Departments for Chest Paina

| Results, N |

|||||||

| Study | N | Anginal w/PD | Anginal w/o PD | Nonanginal w/PD | Nonanginal w/o PD | Criteria for Angina | Criteria for Panic Disorder |

| Yingling et al,19 1993 | 229 | 9 | 19 | 31 | 170 | Substernal + Exertional + Relief With Nitroglycerine/Rest | PDSRS |

| Fleet et al,18 1997 | 180 | 14 | 76 | 33 | 57 | Substernal + Exertional + Relief With Nitroglycerine/Rest | ADIS-R |

| Fleet et al,74 2000 | 441 | 27 | 159 | 81 | 174 | Substernal + Exertional + Relief With Nitroglycerine/Rest | ADIS-R |

Adapted with permission from Katerndahl.16

Abbreviations: ADIS-R = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised, PD = panic disorder, PDSRS = Panic Disorder Self-Rating Scale.

Other specific characteristics of the chest pain may help to distinguish between panic disorder and other causes of chest pain. Some characteristics normally thought to indicate coronary disease, such as the occurrence of chest pain with exertion, a pressure sensation,9,14 and a substernal9 or precordial location,14,90 are also associated with anxiety or panic disorder. But chest pain with anxiety or panic has also been described as non-exertional14; dyspeptic86; associated with meals22 or nervousness22; present at night9; and located in the chest wall,90 right hand,87 or forearm, but not in the left back.76 Exertional pattern and relief with nitroglycerin have poor predictive validity in primary care settings.91

Chest pain in patients with normal coronary angiograms should be due to noncardiac causes. However, studies of chest pain patients with normal coronary angiograms report that 13% of these patients have angina and 73% have atypical angina.13 In addition, 17% to 59% have abnormal electrocardiograms, with 4% to 73% showing ST depression with exercise. Also, nitroglycerin relieves chest pain in 18% to 64% of these patients.2 In addition, patients without significant coronary disease report more associated dyspnea and sweating.11 However, compared to patients with ischemic heart disease, those with normal angiograms have similar levels of pain and psychosocial stress and use similar coping strategies.92 Thus, although certain atypical features may suggest panic disorder, many of the characteristics classically associated with CAD are common in patients with panic disorder or anxiety.

Recognition of panic disorder.

Certain patient characteristics suggest which patients with chest pain should be screened for panic disorder. Table 3 shows that younger age and psychiatric symptomatology and diagnoses are consistent correlates of panic disorder. However, not all studies support the importance of age or gender.19,26,27,35,83 These findings agree with the observation that female sex, younger age, atypical chest pain, normal results on the exercise treadmill test, and panic disorder are predictors of negative cardiac testing in patients with chest pain.25 In general, panic disorder should be suspected in patients with atypical chest pain, lack of organic causes of chest pain, asymptomatic MVP, and palpitations without significant arrhythmia.94

Table 3.

Correlates With the Presence of Panic Disorder in Patients With Chest Paina

| Population | Correlates |

| Primary care | Elevated anxiety level90 |

| Emergency | Younger age18,19,74 |

| department | Atypical chest pain18 |

| Elevated levels: | |

| Depression74 | |

| Anxiety74 | |

| Phobia74 | |

| Cardiology | Demographics: |

| Younger age29 | |

| Female29 | |

| Unemployed29 | |

| Less education29 | |

| Lower income29 | |

| Elevated levels: | |

| Pain23, 29 | |

| Hypochondriasis23 | |

| Somatosensory amplification29 | |

| Presence of: | |

| Agoraphobia23 | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder23 | |

| Major depression23 | |

| Somatoform disorder23 | |

| Personality disorder (i.e., borderline personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder)93 |

Reprinted with permission from Katerndahl.16

Which patients presenting to emergency department and primary care physicians should be screened for panic disorder on the basis on these studies? First, the high prevalence of panic disorder in patients with chest pain (see Table 1) suggests that physicians should have a high index of suspicion for panic disorder in every patient seen with chest pain. Second, certain demographic groups (younger age, female) deserve particular attention. In addition, certain pain characteristics (atypical chest pain, noncardiac description, pain in the right arm or hand) and agoraphobic cognitions or behaviors should increase the index of suspicion. Patients without organic causes of chest pain, with MVP, or with normal cardiac testing also deserve attention.

Although lactate infusion, CO2 inhalation, hyperventilation, CO2 rebreathing,95 and breath-holding96 can induce panic attacks in research settings, these tests are not sensitive enough to be useful clinically. A recent meta-analysis found 5 consistent correlates of panic disorder among patients with chest pain—female sex, younger age (< 50 years old), atypical chest pain, high anxiety levels, and lack of CAD—leading the authors to advocate panic disorder screening for patients who have at least 2 of these correlates.97 Predictive models of panic disorder in emergency department patients with chest pain have been developed and include female sex, agoraphobic cognitions, patient mobility, sensory-type pain (as opposed to emotional pain), and pain location (right forearmbut not back).18 Similar predictive models of panic disorder among cardiology patients with chest pain include younger age, agoraphobic cognitions, somatization, affective-type pain (emotion-related pain), and pain location (palm of the right hand)29 (see Table 3).

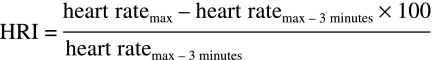

In addition, if an episode of chest pain develops in the office or emergency department, heart rate measurements could potentially be used as a marker for panic attacks. Based on laboratory-based research during lactate infusions, changes in heart rate during symptoms may be useful in recognizing a panic attack. Using heart rate measurements every minute during an episode, the heart rate index (HRI) can be calculated using the maximal heart rate and the heart rate at 3 minutes prior to maximal:

|

If the HRI ≥ 10, the probability that the episode is a panic attack is increased (sensitivity = 85%, specificity = 74%).98

Despite these predictive models and the HRI, these tests with positive likelihood ratios < 5 and negative likelihood ratios generally > 0.2 (Tables 4 and 5) are not good enough to use as diagnostic tests for panic disorder.99 Panic disorder should be diagnosed via DSM criteria.

Table 4.

Decision Tools for Recognizing Panic Disorder

| Criteria | Setting | Accuracy | + LR | −LR |

| Fleet et al18 | Emergency18 | 73% | 2.6 | .45 |

| Emergency18 | 84% | 8.4 | .44 | |

| Dammen et al29 | Cardiology29 | 73% | 3.1 | .52 |

| Cardiology29 | 78% | 4.6 | .41 | |

| Heart Rate Index | Psychiatry98 | 80% | 3.3 | .20 |

Symbols: +LR = positive likelihood ratio, –LR = negative likelihood ratio.

Table 5.

Two Models of Criteria for Recognizing Panic Disorder in Chest Pain Patients

| Fleet et al.18 | Dammen et al.29 |

| Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire score | Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire score |

| Mobility Inventory for Agoraphobia-accompanied subscale score | SCL-90-somatization subscale score |

| Severity of chest pain | |

| Pain in right forearm | Absence of pain in right palm |

| Absence of pain in left upper back | Younger age |

Abbreviation: SCL-90 = Symptom Checklist-90.

If, after applying DSM criteria, it is still unclear whether the patient has panic disorder, a drug trial may be useful. Although response to sublingual nitroglycerin may be helpful in angina, the frequent occurrence of esophageal abnormalities in panic disorder100 and the response of esophageal spasms to nitroglycerin suggest that response to nitroglycerin would not exclude other cases. A trial of high-potency benzodiazepines may also be helpful. Alprazolam decreases chest pain and panic attack frequency in panic disorder patients with chest pain,101 and clonazepam decreases anxiety levels and panic attack frequency in panic disorder patients with chest pain and normal coronary angiograms, but even a placebo can decrease panic attack frequency.102 In addition, sertraline reduces pain levels in patients with noncardiac chest pain.103 Although not evaluated in patients with panic disorder and chest pain, propranolol may be helpful in distinguishing panic disorder and CAD from other causes of chest pain on the basis of its ability to correct the false positive electrocardiogram observed in patients with MVP,104 or, presumably, CAD.

CONCLUSION

Chest pain is a common symptom in primary care patients, often leading to disability and care-seeking. The source of the chest pain during panic attacks may be ischemic. Thus, recognition of panic disorder in chest pain patients, while often missed, is critical. Although atypical chest pain may suggest panic disorder, this symptom can be misleading. Proposed decision tools and testing for the presence of panic disorder have inadequate likelihood ratios to be useful clinically. Ultimately, the diagnosis of panic disorder must be based on DSM criteria. However, once panic disorder is recognized, clinicians must remain open to the possibility of co-occurring CAD. Future research needs to study the prevalence and recognition of panic disorder among patients with chest pain presenting in primary care settings.

Drug names: alprazolam (Xanax, Niravam, and others), aminophylline (Truphylline and others), clonazepam (Klonopin and others), clonidine (Catapres, Duraclon, and others), doxazosin (Cardura and others), enalapril (Vasotec and others), estrogen (Premarin, Cenestin, and others), imipramine (Tofranil and others), prazosin (Minipress and others), propranolol (Innopran, Inderal, and others), sertraline (Zoloft and others).

Disclosure of off-label usage: The author has determined that, to the best of his knowledge, aminophylline, clonidine, doxazosin, enalapril, estrogen, imipramine, and prazosin are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chest pain with normal angiogram, propranolol for distinguishing between panic disorder and coronary artery disease, sertraline for the treatment of noncardiac chest pain, and nitroglycerin for the treatment of esophageal spasm.

Pretest and Objectives

Instructions and Posttest

Registration Form

Footnotes

Dr. Katerndahl has been a member of the speakers/advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, LeResche L, et al. Epidemiologic comparison of pain complaints. Pain. 1988;32:173–183. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers J, Bass C. Chest pain with normal coronary anatomy. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1990;33:161–184. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(90)90007-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff AD. Common symptoms in ambulatory care. Am J Med. 1989;86:262–266. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroenke K, Arrington ME, Mangelsdorff AD. Prevalence of symptoms in medical outpatients and the adequacy of therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1685–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.150.8.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrest CB, Nutting PA, Starfield B, et al. Family physicians’ referral decisions. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambulatory Sentinel Practice Network. Exploratory report of chest pain in primary care. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1990;3:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klinkman MS, Stevens D, Gorenflo DW. Episodes of care for chest pain. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katerndahl D, Trammell C. Prevalence and recognition of panic states in STARNET patients presenting with chest pain. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitaliano PP, Katon W, Maiuro RD, et al. Coping in chest pain patients with and without psychiatric disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:338–343. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bass C, Wade C. Chest pain with normal coronary arteries. Psychol Med. 1984;14:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329170000307x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aikens JE, Michael E, Lerin T, et al. Cardiac exposive history as a determinant of symptoms and emergency department utilization in non-cardiac chest pain patients. J Behav Med. 1999;22:605–617. doi: 10.1023/a:1018745813664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kane FJ, Jr, Harper RG, Wittels E. Angina as a symptom of psychiatric illness. South Med J. 1988;81:1412–1416. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198811000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Silva RA, Bachman WR. Cardiac consultation in patients with neuropsychiatric problems. Cardiol Clin. 1995;13:225–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho KY, Knag JY, Yeo B, et al. Non-cardiac, non-esophageal chest pain. Gut. 1998;43:105–110. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katerndahl DA. Panic and plaques: panic disorder & coronary artery disease in patients with chest pain. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004 Mar–Apr;17(2):114–126. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katerndahl DA. Symptom severity and perceptions in subjects with panic attacks. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1028–1035. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al. Detecting panic disorder in emergency department chest pain patients. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:124–131. doi: 10.1007/BF02883329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yingling KW, Wulsin LR, Arnold LM, et al. Estimated prevalences of panic disorder and depression among consecutive patients seen in an emergency department with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:231–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02600087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wulsin LR, Hillard JR, Geier P, et al. Screening emergency room patients with a typical chest pain for depression and panic disorder. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1988;18:315–323. doi: 10.2190/9hj2-vk0h-xjyg-mkq6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mateos JLA, Perez CB, Carrasco JSD, et al. Atypical chest pain and panic disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 1989;52:92–95. doi: 10.1159/000288305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane FJ, Jr, Strohlein J, Harper RG. Noncardiac chest pain in patients with heart disease. South Med J. 1991;84:847–852. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dammen T, Arnesen H, Ekeberg O, et al. Panic disorder in chest pain patients referred for cardiological outpatient investigation. J Intern Med. 1999;245:497–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearce MJ, Mayou RA, Klimes I. Management of atypical non-cardiac chest pain. Quart J Med. 1990;76:991–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cormier LE, Katon W, Russo J, et al. Chest pain with negative cardiac diagnostic studies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176:351–358. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charney RM, Freedland RE, Ludbrook PA, et al. Major depression, panic disorder, and mitral valve prolapse in patients who complain of chest pain. Am J Med. 1990;89:757–760. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beitman BD, Lamberti JW, Mukerji V, et al. Panic disorder in patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries. Psychosomatics. 1987;28:480–484. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(87)72479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg R, Morris P, Christian F, et al. Panic disorder in cardiac outpatients. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:168–173. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(90)72190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dammen T, Ekeberg O, Arnesen H, et al. Detection of panic disorder in chest pain patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21:323–332. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chignon JM, Lepino JP, Ades J. Panic disorder in cardiac outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:780–785. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleet R, Lavoie K, Beitman BD. Is panic disorder associated with coronary artery disease? J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:347–356. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korczak DJ, Goldstein BI, Levitt AJ. Panic disorder, cardiac diagnosis and emergency department utilization in an epidemiologic community sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carter C, Maddock R, Amsterdam E, et al. Panic disorder and chest pain in the coronary care unit. Psychosomatics. 1992;33(3):302–309. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(92)71969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katon W, Hall ML, Russo J, et al. Chest pain: relationship of psychiatric illness to coronary arteriographic results. Am J Med. 1988;84:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al. Panic disorder, chest pain and coronary artery disease: literature review. Can J Cardiol. 1994 Oct;10(8):827–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conti S, Savron G, Bartolucci G, et al. Cardiac neurosis and psychopathology. Psychother Psychosom. 1989;52:88–91. doi: 10.1159/000288304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dammen T, Bringager CB, Arnesen H, et al. 1-year follow-up study of chest-pain patients with and without panic disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Argyle N, Roth M. The definition of panic attacks, part 1. Psychiatr Dev. 1989;7(3):175–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Margraf J, Taylor CB, Ehlers A, et al. Panic attacks in the natural environment. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175:558–565. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch P, Bakal DA, Whitelaw W, et al. Chest muscle activity and panic anxiety. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:80–89. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.York KM, Hassan M, Li Q, et al. Do men and women differ on measures of mental stress-induced ischemia? Psychosom Med. 2007;69:918–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815a9245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramachandruni S, Fillingim RB, McGorray SP, et al. Mental stress provokes ischemia in coronary artery disease subjects without exercise- or adenosine-induced ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:987–991. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fleet R, Lesperance F, Arsenault A, et al. Myocardial perfusion study of panic attacks in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1064–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balon R, Ortiz A, Pohl R, et al. Heart rate and blood pressure during placebo-associated panic attacks. Psychosom Med. 1988;50:434–438. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198807000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeragani VK, Balon R, Pohl R, et al. Decreased R-R variance in panic disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81:554–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Middleton HC. Cardiovascular dystonia in recovered panic patients. J Affect Dis. 1990;19:229–236. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90099-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeragani VK, Pohl R, Balon R, et al. Heart rate in panic disorder (letter) Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991 Jan;83(1):79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb05516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bystritsky A, Maidenberg E, Craske MG, et al. Laboratory psychophysiological assessment and imagery exposure in panic disorder patients. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12:102–108. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:2<102::AID-DA7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shear MK, Kligfield P, Harshfield G, et al. Cardiac rate and rhythm in panic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:633–637. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldberger AL, Rigney DR, Mietus J, et al. Nonlinear dynamics in sudden cardiac death syndrome. Experientia. 1988;44:983–987. doi: 10.1007/BF01939894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JAC, et al. Neurohumeral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chestire WP, Achem SR. Synchrony of syncope. Clin Auton Res. 2004;14:44–48. doi: 10.1007/s10286-004-0161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks, daily life ischemia, and chest pain in postmenopausal women. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:824–832. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000244383.19453.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavoie KL, Fleet RP, Laurin C, et al. Heart rate variability in coronary artery disease patients with and without panic disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2004 Oct;128(3):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Von Kanel R, Kudielka BM, Schulze R, et al. Hypercoagulability in working men and women with high levels of panic-like anxiety. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73:353–360. doi: 10.1159/000080388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katon WJ. Chest pain, cardiac disease, and panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990 May;51(suppl):27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reis SE, Holubkov R, Smith AJC, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with chest pain in the absence of coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2001;141:735–741. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roy-Byrne PP, Schmidt P, Cannon RO, et al. Microvascular angina and panic disorder. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1989;19:315–325. doi: 10.2190/5j4t-penr-2g3f-aue0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Braunwald E, Zipes DP, Libby P. Heart Disease. 6th ed. New York, NY: W.B. Saunders Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gomez-Caminero A, Blumenthal WA, Russo LJ, et al. Does panic disorder increase the risk of coronary heart disease? Psychosom Med. 2005;67:688–691. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000174169.14227.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wasserthell-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks and risk of incident cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women in the Women's Health Initiataive Observational Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1153–1160. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gallerani M, Manfredini R, Mele D, et al. Can panic disorder be considered as an angina equivalent? Eur Heart J. 1995;16(12):2013–2014. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katerndahl DA. Illness attitudes and coping process in subjects with panic attacks. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999 Sep;187(9):561–565. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beitman BD, Kushner M, Lamberti JW, et al. Panic disorder without fear in patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178:307–312. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199005000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kroeze S, Van Den Houst MA. Selective attention for cardiac information in panic patients. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aikens JE, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Differential fear of cardiopulmonary sensations in emergency room noncoardiac chest pain patients. J Behav Med. 2001;24:155–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1010710614626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al. Panic disorder in coronary artery disease patients with noncardiac chest pain. J Psychosom Res. 1998;44:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katerndahl DA, Realini JP. Use of health care services by persons with panic symptoms. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1027–1032. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katerndahl DA, Realini JP. Where do panic attack sufferers seek care? J Fam Pract. 1995;40:237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swinson RP, Cox BJ, Woszczyna CB. Use of medical services and treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia and for social phobia. CMAJ. 1992 Sep;147(6):878–883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Candilis PJ, Mchean RS, Otto MW, et al. Quality of life in patients with panic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:429–434. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Katerndahl DA. Factors in the panic-agoraphobia transition. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1989;2:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Katerndahl DA, Realini JP. Quality of life and panic-related work disability in subjects with infrequent panic and panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997 Apr;58(4):153–158. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fleet RP, Martel JP, Lavoie KL, et al. Non-fearful panic disorder. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:311–320. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Kaczorowski J, et al. Suicidal ideation in emergency department chest pain patients: panic disorder a risk factor. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15(4):345–349. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Realini JP, Katerndahl DA. Factors affecting the threshold for seeking care: the Panic Attack Care-Seeking Threshold (PACT) study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1993;6:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katerndahl DA. Factors associated with persons with panic attacks seeking medical care. Fam Med. 1990;22:462–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salvador-Carulla L, Segui J, Fernandez-Cano P, et al. Costs and offset effect in panic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1995 Apr;(Suppl)(27):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ross CA, Walker JR, Norton GR, et al. Management of anxiety and panic attacks in immediate care facilities. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988;10:129–131. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aikens JE, Wagner LI, Lickerman AJ, et al. Primary care physician responses to a panic disorder vignette: diagnostic suspicion and clinical management. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28(2):179–188. doi: 10.2190/3ATH-C9F4-2RTA-PXHA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cox BJ, Swinson RP, Endler NS, et al. Symptom structure of panic attacks. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35:349–353. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(94)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bovasso G, Eaton W. Types of panic attacks and their association with psychiatric disorder and physical illness. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40:469–477. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kushner MG, Beitman BD, Beck NC. Factors predictive of panic disorder in cardiology patients with chest pain and no evidence of coronary artery disease. J Psychosom Res. 1989;33:207–215. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beitman BD, Basha I, Flaker G, et al. Atypical or nonarginal chest pain. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1548–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Basha I, Mukerji V, Langerin P, et al. Atypical angina in patients with coronary artery disease suggest panic disorder. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1989;19:341–346. doi: 10.2190/ak3t-v52n-7d5y-gff6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beitman BD. Panic disorder in patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries. Am J Med. 1992 May;92(5A):33S–40S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bass C, Chambers JB, Kiff P, et al. Panic anxiety and hyperventilation in patients with chest pain. Quart J Med. 1988;69:949–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Alpert MA, Mukerji V, Sabeti M, et al. Mitral valve prolapse panic disorder, and chest pain. Med Clin N Am. 1991;75:1119–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beitman BD, Mukerji V, Lamberti JW, et al. Panic disorder in patients with chest pain and angiographically normal coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:1399–1403. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)91056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cope RL. Psychogenic factor in chest pain. Tex Med. 1969;65:78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sox HC, Jr, Hickam DH, Marton KI, et al. Using the patients's history to estimate the probability of coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1990;89:7–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90090-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zachariae R, Melchiorsen H, Frobart O, et al. Experimental pain and psychologic status of patients with chest pain with normal coronary arteries or ischemic heart disease. Am Heart J. 2001;142:63–71. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.115794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dammen T, Ekeberg O, Arnesen H, et al. Personality profiles in patients referred for chest pain. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:269–276. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jeejeebhoy FM, Dorian P, Newman DM. Panic disorder and the heart. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:393–403. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Papp LA, Martinez JM, Klein DF, et al. Rebreathing tests in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:240–245. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00296-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nardi AE, Nascimento I, Valenca AM, et al. Panic disorder in a breath-holding challenge test: a simple tool for a better diagnosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003 Sep;61(3B):718–722. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2003000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huffman JC, Pollack MH. Predicting panic disorder among patients with chest pain. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:222–236. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.3.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gorman JM, Davies M, Steinman R, et al. Objective marker of lactate-induced panic. Psychiatry Res. 1987;22:341–348. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(87)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature, 3. How to use an article about a diagnostic test, B: what are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994;271:703–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maunder RG. Panic disorder associated with gastrointestinal disease: review and hypotheses. J Psychosom Res. 1998;44(1):91–105. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Beitman BD, Basha IM, Trombka LH, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic treatment of panic disorder in patients presenting with chest pain. J Fam Pract. 1989;28:177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wulsin LR, Maddock R, Beitman B, et al. Clonazepam treatment of panic disorder in patients with recurrent chest pain and normal coronary arteries. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29:97–105. doi: 10.2190/X6N2-8HYG-7LLJ-X6U2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Krishnan KR. Chest pain and serotonin. Gastroenterology 2001;121:496–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cheng TO. Mitral valve prolapse versus panic disorder in patients with chest pain (letter) J Intern Med. 2000;247:518–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]