Abstract

In the K/BxN mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis, autoantibodies specific for glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) can transfer joint-specific inflammation to most strains of normal mice. Binding of GPI and autoantibody to the joint surface is a prerequisite for joint-specific inflammation. However, how GPI localizes to the joint remains unclear. We show that glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are the high affinity (83 nm) joint receptors for GPI. The binding affinity and structural differences between mouse paw/ankle GAGs and elbows/knee GAGs correlated with the distal to proximal disease severity in these joints. We found that cartilage surface GPI binding was greatly reduced by either chondroitinase ABC or β-glucuronidase treatment. We also identified several inhibitors that inhibit both GPI/GAG interaction and GPI enzymatic activities, which suggests that the GPI GAG-binding domain overlaps with the active site of GPI enzyme. Our studies raise the possibility that GAGs are the receptors for other autoantigens involved in joint-specific inflammatory responses.

A defining characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)3 is the painful inflammation of synovial joints of the wrists and fingers. The K/BxN murine model of RA emulates human RA joint specificity; inflammation is much more prominent in the paws and ankles of the mouse than in the knees or hips. The autoantigen in the K/BxN model (1–3) is glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) (EC 5.3.1.9), an essential cytoplasmic enzyme. This enzyme is required for glucose utilization in every cell, but it is also present in the extracellular fluid. When anti-GPI antibodies (Ab) from K/BxN serum are transferred to most strains of normal mice, synovial arthritis similar to RA is elicited (2, 4, 5). We and others demonstrated that within minutes of the Ab transfer, anti-GPI (αGPI) IgG localizes specifically to the joints where arthritis occurs (5, 6). This IgG joint localization is dependent on Fc receptors, neutrophils, and mast cells (2). αGPI autoantibodies bound to the GPI on the articular cartilage in normal mice (5, 6). However, the nature of GPI receptors in the joint is unknown.

Based on histological features, including the number of chondrocytes and their morphology, collagen fiber orientation, and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) concentration, articular cartilage has four distinct layers, superficial, middle, deep, and calcified. GAGs are abundantly expressed in all layers of cartilage. GAGs, such as heparan sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS), consist of repeating disaccharides of a uronic acid and a glycosamine. The incomplete epimerization of GlcA to iduronic acid and sulfation at different positions of repeating disaccharides in HS give rise to 48 possible disaccharide structures, of which 23 have been found (7). Because of building block-disaccharide complexity, GAGs are the most information-dense biopolymers found in nature. Transgenic and knock-out animal data in the past decade provide compelling evidence that animals use precise GAG sequences in multicellular communications (7).

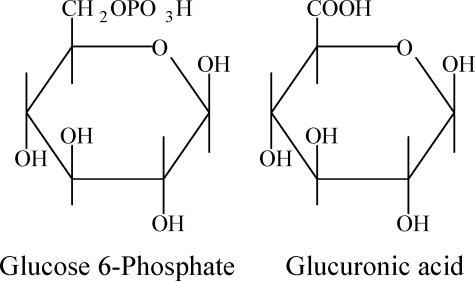

GAG sequences are not directly encoded by genes but are assembled in the Golgi by enzymes encoded by over 40 genes. Because of the vast expression repertoire of the GAG assembly enzymes and existence of GAG structural modification enzymes in extracellular matrix, GAGs display a sulfation pattern, chain length, and fine structure unique to each cell and tissue (8). GlcA is structurally similar to the natural substrate of GPI, glucose 6-phosphate (Structure 1). We hypothesize that GPI binds to GlcA residues of GAGs on the cartilage surface via its active site, providing a joint-specific target for anti-GPI Ab.

STRUCTURE 1.

The results in this study support our hypothesis. In addition, several inhibitors of this GPI/GAG interaction were identified. Our results suggested that the distal to proximal distribution severity of arthritis in K/BxN mice could be accounted for by the difference in GAG structures we found in small versus large joints, and a differential ability to bind GPI may set up the threshold in initiating the anti-GPI autoimmune response.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

GAG Isolation from Joints—Joint samples, including ∼3-mm bones on both sides of joint, were harvested from BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks of age). External skin and muscle were removed, and the wet weight of each sample pool (paws/ankle or knees/elbows) was recorded after the intact joints were washed and blotted dry. The samples were scissor-minced and then transferred to 50-ml conical tubes containing 1 ml/g wet weight (but a minimum 0.5 ml of water). The samples were homogenized with a Polytron. GAGs were then isolated by DEAE-Sephacel chromatography followed by ethanol precipitation as described in Studelska et al. (9).

GAG Quantification—The steps were acid hydrolysis, sodium borohydride reduction, precolumn derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde and 3-mercaptopropionic acid, and reversed phase HPLC separation with fluorescence detection of the isoindole derivatives. GAG aliquots containing 6 nmol of norleucine as an internal standard were dried in pyrolized glass vials (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, part 5181-8872) before hydrolysis with HCl vapor in N2 gas at 100 °C for 3 h. The samples were rehydrated in 45 μl of 0.56% NaBH4 to reduce the glucosamine and galactosamine liberated by acid hydrolysis into glucosaminitol and galactosaminitol, respectively. After 3 h or overnight at room temperature, the reaction was terminated by adding 5 μl of 2 n acetic acid to each vial. A 5-μl aliquot of each hydrolyzed and reduced sample was transferred to a fresh auto-sampler insert vial for precolumn derivatization with 35 μl of 7.5 mm o-phthaldialdehyde, 375 mm 3-mercaptopropionic acid, in 0.4 n borate adjusted to pH 9.3 with NaOH. Half of this reaction mixture was injected onto a 4.6 × 250-mm C-12 column, a Synergi 4μ MAX-RP 80 Å (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, part 00G-4337-E0), heated to 35 °C. The column was equilibrated with Buffer A, consisting of 0.05 m (monobasic and dibasic) sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, in 25% methanol, at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. Buffer B consisted of methanol/water/tetrahydrofuran at 70:30:3 volume ratios. After injection, Buffer B was increased from 0 to 8% by a linear gradient between 0 and 3 min, was maintained at 8% between 3 and 18 min, at 55% between 18 and 30.5 min, at 100% between 30.5 and 32.5 min, and at 0% between 32.5 and 35 min. A 5-min post-run interval at 0% B precedes the initiation of the next precolumn derivatization injection sequence. The fluorescent derivatives of glucosaminitol, galactosaminitol, and the amino acids contained in the GAG preparations were excited at 337 nm and detected at 454 nm. A more detailed description of this assay is available elsewhere (9).

Iodination of GPI—Thirty μg of recombinant mouse GPI was labeled with 125I (as Na125I, Amersham IMS-30) by the Chizzonite indirect method using IODO-GEN® pre-coated tubes (Pierce 28601) and the protocol supplied by the vendor. Tris/NaCl/EDTA buffer was used instead of Tris/BSA buffer for column washing, fraction collection, and protein dilution after labeling.

Gel Mobility Shift Assay—We increased the sensitivity of published gel mobility shift assay (10) by using 125I-labeled GPI in nanomolar ranges instead of 35S-labeled GAGs, which require micromolar range of GAG-binding proteins in the binding reactions. We also improved the gel mobility shift assay by loading the sample in the middle of the gel and allowing protein to move either to cathode or anode depending on its physiological pI (10). Briefly, the two directional native-horizontal gel was performed with 4.5% polyacrylamide gels using 0.12% piperazine diacrylamide as a cross-linker. The gels contained 10 mm Tris, adjusted to pH 7.4 with HAc. The 50-ml gels were poured in a casting stand for a Screener RG100 horizontal gel apparatus (Biokey American Instruments, Inc., Beaverton, OR), with a 13- or 26-well comb placed in the middle. To hasten polymerization, higher than usual amounts of TEMED (50 μl), and ammonium persulfate (1.0 ml of a 10% solution) were employed. In the Screener RG100, anodal and cathodal buffer chambers were sealed by the ends of the gel, which was overlaid with 350 ml of water in a center chamber. The water cools the gel during electrophoresis, allowing higher voltages and longer runs. The buffer chambers were filled with a running buffer consisting of 40 mm Tris and 40 mm acetic acid, adjusted to pH 7.4. Each component of a binding reaction, i.e. GAGs and other components such as GPI inhibitors, was added in binding buffer, 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 4.3 mm Na2HPO4, 1.4 mm KH2PO4, 12% glycerol, and pH adjusted to 7.4. After the addition of 125I-GPI, the last component, to give a final enzyme concentration of 50 nm, the binding reaction volume was 12 μl. After 20 min at room temperature, 5-μl aliquots of each reaction were pipetted through water into the bottom of wells pre-filled with binding buffer containing 8% glycerol, which overlaid the denser binding reaction mixture. Electrophoresis was at 20 watts until xylene cyanole dye, loaded into one of the end wells, eluted from the gel. The gel was dried onto blotting paper in a gel dryer at 70 °C before it was placed in a GE Healthcare cassette for exposure to a storage phosphor screen (Eastman Kodak Co.) The screen was read in a Storm 840 PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare). The radioactivity values of the GPI migrating toward the cathode were measured by NIH Image software (10).

Flow Cytometric Analysis of GPI Binding—CHO 745 cells, CHO CS, or CHO HS&CS cells were treated with EDTA to lift them off culture plates, and binding of GPI was performed with 5 μg of recombinant mouse GPI on ice for 30 min. GPI binding was detected with 1 μg of αGPI monoclonal antibody 147 followed by goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody. Negative controls included αGPI monoclonal antibody 147 plus goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody without GPI preincubation, or goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody alone. Samples were collected on BD FACSCalibur with 10,000 cells analyzed by FlowJo.

Immunohistology of Joint GPI Stain—Paraffin sections from ankle and knee joints were prepared. K/BxN serum was used as the primary antibody for joint stain. Serial 6-μm sections were de-paraffinized and air-dried for 1 h at room temperature followed by washing with PBS. Sections were fixed with 50% acetone in PBS for 10 min on ice, incubated with PBS containing 2 m NaCl (pH 7.4) for 10 min at room temperature to remove GAG-binding proteins, and blocked in PBS containing 0.5% BSA overnight at 4 °C. In some experiments, sections were treated with enzymes at 37 °C for 2 h to digest selected GAG structures. Subsequently, sections were incubated with 20 nm recombinant mouse GPI for 30 min, followed by incubation with 1:50 diluted sera of arthritic K/BxN mice in PBS containing 0.5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes, sections were incubated with Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:200. Negative controls included 1:50 diluted sera of arthritic K/BxN mice plus goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody without GPI preincubation, or goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody alone. Nuclear staining was achieved by incubation for 15 min with a 1:2,500 dilution of To-Pro-3 (Invitrogen). Sections were mounted using fluorescent mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed using a Zeiss 510 Meta LSM confocal microscope. To quantify the staining intensity, we used imaging software (Carl Zeiss version 3.2) of the Zeiss 510 Meta LSM confocal microscope to integrate the mean intensity of GPI staining (green) and mean intensity of nuclear staining (blue) of each image, and then we calculated the intensity ratio.

GPI Enzyme Kinetics—We assayed the GPI-catalyzed conversion of fructose 6-phosphate (Fru-6-P) to glucose 6-phosphate by monitoring the activity of a second enzyme, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, which catalyzes the oxidation of glucose 6-phosphate and the coupled reduction of NADP to UV-absorbing NADPH (11). Parallel 200-μl reactions were monitored at 340 nm and 37 °C using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Sunnyvale, CA) in the absorbance mode. At a final dilution, each well contained 4.2 units/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Sigma G-6378), 1.0 mm NADP (Sigma N0505), 0.4 μg/ml recombinant mouse GPI, and inhibitors at various concentrations in 50 mm Tris, 88 mm KCl, pH 8.0. After equilibration at 37 °C, the reactions were initiated by the addition of 20 μl of Fru-6-P (Sigma F1502) for a final Fru-6-P concentration of 2 mm. Absorbances of up to eight reactions were read every 3 s during an 8-min run. Vmax values were estimated using Softmax Pro 4.6. Because this is a coupled two-enzyme system, we tested the effect of our putative GPI inhibitors on glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in separate control experiments and found them to have no direct effect on glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Capillary HPLC-coupled Mass Spectrometry—GAGs were exhaustively digested by chondroitinase ABC. The resulting mono-, di-, tri, tetra-, and oligosaccharides were analyzed by capillary HPLC-coupled MS. An Agilent 1100 series capillary HPLC workstation (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) with Chemstation software was used for data acquisition, analysis, and management. HPLC separations were performed on a 0.3 × 250-mm C18 column (Zorbax 300SB, 5 μm, Agilent) using a binary solvent system composed of 5% methanol (eluent A) and 90% methanol in water (eluent B); both contained 3.5 mm dibutylamine and were adjusted to pH 5.5 with 2 m HAc. After injection of a 0.5-μl sample, the elution profile was 0% B for 7 min, 15% B for 9 min, 40% B for 11 min, and 100% B for 23 min. The flow rate was 5 μl/min, and absorbances at 232, 260, and 280 nm were monitored during each run. After each run the column was washed with 90% B for 15 min and equilibrated with 100% A for 40 min. The capillary HPLC was directly coupled to the mass spectrometer. Mass spectra were acquired on a Mariner BioSpectrometry workstation electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) in the negative ion mode. Nitrogen was used as a desolvation gas as well as a nebulizer. Conditions for electrospray ionization-MS were as follows: nebulizer flow, 1 liter/min; nozzle temperature, 140 °C; N2 flow, 0.1 liter/min; spray tip potential, 2.8 kV; nozzle potential, 70 V; and skimmer potential, 9 V. Negative ion spectra were collected by scanning the m/z range 150–1000. During analyses, the vacuum was 2.1 × 10- 6 torr. TIC chromatograms and mass spectra were processed with Data Explorer software version 3.0.

RESULTS

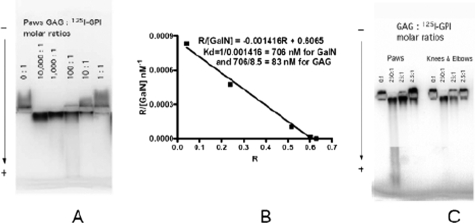

GPI Binds to Joint GAGs—It is unknown how GPI binds to the articular cartilage. Because GlcA is a component of joint GAGs and is similar to the natural substrate of GPI, glucose 6-phosphate, we hypothesized that GPI was able to bind to GlcA residues of joint GAGs via its catalytic site. To test this, GAGs were extracted from mouse paw/ankle and elbow/knee (see under “Experimental Procedures”) and then quantified by our published method (9). Equal amounts of galactosamine containing GAGs were used in a gel mobility shift assay to measure GPI/GAG interaction. This solution-phase test of protein/GAG interaction has been used to measure binding affinity between GAG and proteins (10, 13). Using the gel mobility shift assay, we showed that GPI could bind to mouse paw/ankle GAGs (Fig. 1A). Recombinant GPI migrated toward the anode, demonstrating that GPI has a net positive charge at pH 7.4 (Fig. 1A). Paw/ankle GAGs bind to GPI and reverse the direction of GPI migration from anode to cathode, the same direction as negatively charged GAGs. The magnitude of this GAG effect is dependent upon GAG concentration. A molar ratio of 100 galactosamine to 1 GPI substantially reversed the direction of GPI migration. The GPI/GAG interaction was of high affinity, with a KD calculated to be 83 nm. Thus, GPI is able to bind directly and strongly to GAGs.

FIGURE 1.

GAGs from mouse paws/ankles and knees/elbows bind GPI with different affinity. Gel mobility shift assay with 50 nm 125I-GPI in each lane is shown. A, each lane contained 50 × (0, 10,000, 1000, 100, 10, 1) nm of galactosamine-equivalent GAGs, respectively, from left to right. B, graphic analysis of binding affinity between GPI and mouse paws/ankles GAG based on the data presented in A. The binding affinity between GAG and GPI was estimated by the method developed by Lee and Lander (12) where a retardation coefficient R (R = (Mo - M)/Mo; where M is migration distance) was introduced to measure affinity for the gel mobility assay. The dissociation constant Kd was derived from the R versus R/[GalN] plot shown. Paw/ankle GAG had an average chain length of 21 saccharides, which equals 8.5 disaccharides plus a linkage tetrasaccharide. Thus, a KD of 83 nm for paw/ankle GAGs (706 nm per disaccharide divided by 8.5 disaccharides) was derived. C, each lane contained 50 × (0, 250, 25, 2.5) nm of galactosamine-equivalent GAGs. Left panel, GAGs from paws. Right panel, GAGs from knees and elbows. The experiments were repeated three times. Each time, independent GAG preparations from paw/ankle and knee/elbow joints of BALB/c mice and two additional murine strains, (B6xNOD)F1 and K/BxN, were used. The observation of the superior potency of paw/ankle GAGs to knee/elbow GAGs was replicated in every instance.

GAGs from Paws/Ankles Have Higher GPI Binding Affinity than Those in Knees/Elbows—In Ab transfer experiments, α-GPI Ig preferentially localized to the paw/ankles. Also, arthritis is more pronounced in the paw/ankles compared with the knees/elbows. To ascertain if this distal to proximal disease severity could be explained by the paw/ankle GAGs having a higher GPI binding capacity, we compared the paw/ankle and knee/elbow GAGs (Fig. 1C). Paw/ankle GAGs display much higher activity than knee/elbow GAGs in this measure of interaction with GPI. The greater activity of paw/ankle GAGs can be seen most clearly at the 25:1 GAG:GPI ratio. To obtain the same activity from knee/elbow GAGs, a 4-fold higher ratio (100:1) was required (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that the paw/ankle GAGs display higher ability to bind GPI, which directly correlates with the observed disease severity.

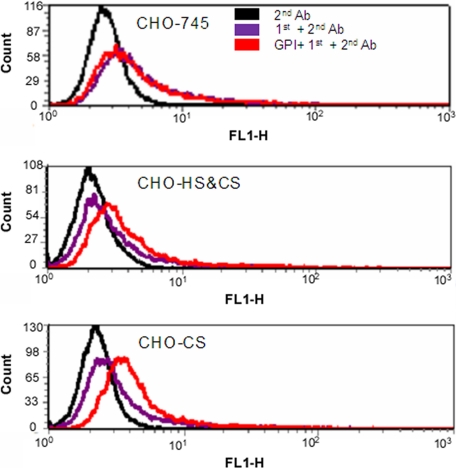

GPI Bound to Cell Surface CS—Having demonstrated that GPI could directly bind to GAGs, we wanted to determine what GAGs were involved in the binding. Quantification of hexosamine content of the isolated GAGs indicated that they were 92–97% galactosamine and therefore CS. The rest of the GAGs (3–8%) contained glucosamine and could be keratan sulfate, heparin, HS, and hyaluronan. To identify the GAGs that bind to GPI, we decided to test cell surface GAGs/GPI interaction by flow cytometry. To show that GPI can directly bind to CS, we took advantage of available GAG-deficient CHO cell lines. CHO cells do not synthesize keratan sulfate and hyaluronan. CHO-745 is a cell mutant defective in xylosyltransferase responsible for initiating both HS and CS biosynthesis (14). As a result, CHO-745 synthesizes little HS and CS (15). CHO CS is an HS-deficient (100% CS) mutant (16–18). CHO HS&CS is a wild-type cell line that synthesizes 70% HS and 30% CS. GPI binding is detected via αGPI monoclonal antibody 147. Binding of αGPI monoclonal antibody 147 was detected by goat anti-mouse Alexa-488. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that GPI binds best to CHO CS cell surface, followed by CHO HS&CS, but not to GAG deficient CHO-745 cells (Fig. 2). αGPI monoclonal antibody 147 plus goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody in the absence of GPI or goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody alone did not show binding on these cells. Thus, GPI showed specific binding to CS. Because 92–97% of joint GAGs are CS, CS is likely the natural ligand of GPI in the joint.

FIGURE 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of GPI binding to CHO cells. Binding of GPI to CHO-745, CHO-HS and CS (CHO-HS&CS), and CHO-CS cells was performed with 1 μg of recombinant mouse GPI on ice. GPI binding was detected with 1 μg of anti-GPI monoclonal antibody followed by goat anti-mouse secondary antibody labeled with Alexa-488. Negative controls include goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody alone (+2nd Ab) and αGPI monoclonal antibody 147 plus goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody (1st+2nd Ab) without GPI preincubation. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

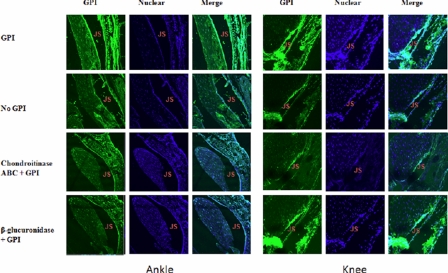

GPI Bound to Cartilage Surface CS—We then determined if GPI binds to joint cartilage surface through specific interaction with in situ CS. To this end, paraffin sections of ankle and knee joints from normal C57BL/6 (B6) mice were prepared. These sections were probed with GPI plus diluted sera of arthritic K/BxN mice followed by Alexa-488-conjugated rat anti-mouse antibody. Cell nuclei were stained with To-Pro-3. Sections were examined by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3). The joint space is outlined on either side by parallel rows of spaced nuclei that belong to the chondrocyte of the superficial layer of articular cartilage. Thin layers of bright continuous GPI staining are found immediately above the chondrocyte layers on either side of the paw joint space, decorating the articular surfaces. Such intensive staining was not observed in the no GPI control and was greatly reduced by either chondroitinase ABC or β-glucuronidase treatments that respectively digest CS or cleave terminal GlcA moieties from CS chains. In contrast, the knee joint cartilage GPI staining was weaker than that of the paw. The staining was also reduced by chondroitinase ABC treatment, but interestingly, it was not affected by β-glucuronidase treatment. GPI staining was also found around the nuclei of chondrocytes, as would be expected for an enzyme with a well established cytoplasmic function. Chondroitinase ABC or β-glucuronidase treatment did not affect this cytoplasmic binding as expected.

FIGURE 3.

CS was the major GPI receptor on cartilage surface. Ankle and knee joint sections were deparaffinized and air-dried. Sections were fixed with 50% acetone in PBS and incubated with PBS containing 2 m NaCl to remove GAG-binding proteins. Sections were treated with either chondroitinase ABC or β-glucuronidase at 37 °C for 2 h to digest selective GAG structures. Subsequently, sections were incubated with 20 nm recombinant mouse GPI, followed by incubation with 1:50 diluted sera of arthritic K/BxN mice. After washing, sections were incubated with Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Negative controls include 1:50 diluted sera of arthritic K/BxN mice plus goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 antibody without GPI preincubation. Nuclear was stained by To-Pro-3. Sections were examined by confocal fluorescence microscopy. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

To quantify the staining intensity, we used imaging software (Carl Zeiss version 3.2) with a Zeiss 510 Meta LSM confocal microscope to calculate the ratio of the intensity of joint surface GPI staining (green) versus nuclear staining of the adjacent chondrocyte layer (blue) (Table 1). The highest ratio, 2.64, was produced by the joint surface of paws. This compares to 1.86 from knee joint surfaces. After adjusting for the background levels observed in the no GPI controls, there is roughly twice as much GPI specifically retained on the paw joint surface. Chondroitinase ABC treatment reduced both paw and knee joint green/blue stain ratios to no GPI background levels. In contrast, β-glucuronidase eliminated specific GPI staining in paw joints but had no effect on GPI on knee joints surfaces. These results suggest that CS is essential for sequestering GPI in both joints, but that the basis for the lower level of GPI binding in the knee joint does not involve terminal β-glucuronic acid residues. In contrast, paw cartilage surfaces are replete with CS enriched with terminal β-glucuronic acid residues. These results are consistent with the gel mobility results shown in Fig. 5 and the markedly higher levels of GlcA terminal structures detected in paws by mass spectrometry (Fig. 4).

TABLE 1.

Ratio of the intensity of GPI versus nuclear stains in paws and knees (green, GPI; blue, nuclear)

| Type of staining | Paws (green/blue) | Knees (green/blue) |

|---|---|---|

| GPI | 2.64 | 1.86 |

| No GPI control | 1.27 | 1.14 |

| Chondroitinase ABC + GPI | 1.16 | 1.01 |

| β-Glucuronidase + GPI | 0.93 | 2.20 |

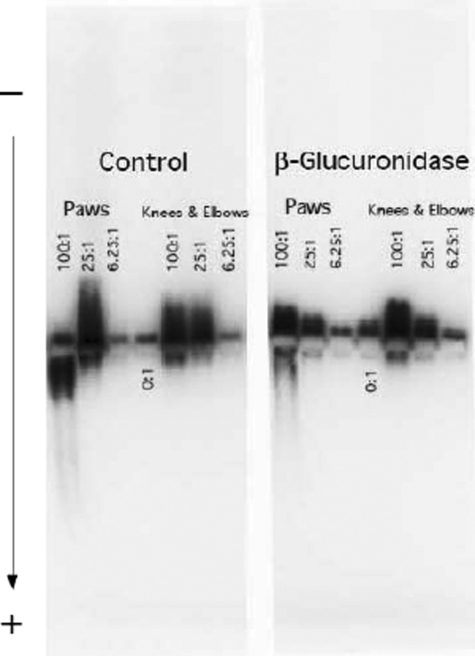

FIGURE 5.

GAG nonreducing end GlcA contributed to high affinity GPI/GAG interaction. Paw/ankle and knee/elbow GAGs (right panel) digested with β-glucuronidase were used in a gel mobility shift assay to determine their effects on GPI binding. The data shown here are representative of three independent experiments. Left panel, control treated with digestion buffer; right panel, β-glucuronidase-treated samples. Each lane contained 50 nm 125I-GPI and 50 × (100, 25, 6.25) nm of galactosamine equivalent GAGs. When GAGs were at low concentration or absent, some 125I-GPI did not enter the gel and was lost.

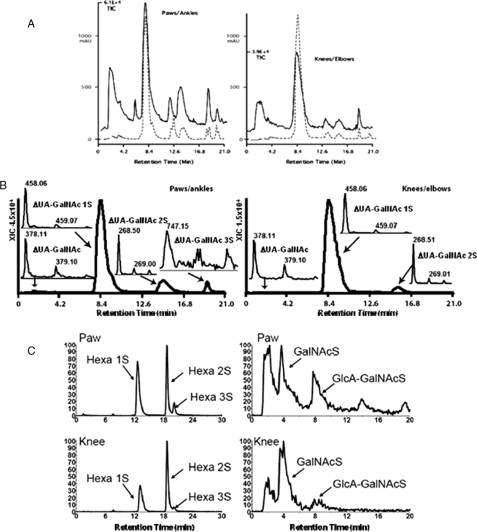

FIGURE 4.

Capillary HPLC-coupled MS analysis of CS GAG structures from mouse paws/ankles and knees/elbows. GAGs were digested by chondroitinase ABC and analyzed by capillary HPLC-coupled MS. A, UV absorbance chromatograms (A232, dashed line) and MS TIC chromatograms (solid line) from paw/ankle (left) or knee/elbow (right). B, XIC of disaccharides. Peak 1 contains ΔUA-GalNAc ([M - H]- 378.1). Peak 2 contains ΔUA-GalNAc 1S ([M - H]- 458.1). Peak 3 contains ΔUA-GalNAc 2S ([M - H]- 268.5). Peak 4 contains ΔUA-GalNAc3S ([M - H]- 747.0). C, left, XIC of linkage hexasaccharides. Hexa1S =ΔUA-GalNAc-GlcA-Gal-Gal-Xylol 1 sulfate (z2 545.6); Hexa2S =ΔUA-GalNAc-GlcA-Gal-Gal-Xylol 2 sulfates (z2 585.6); Hexa3S =ΔUA-GalNAc-GlcA-Gal-Gal-Xylol 3 sulfates. C, right, XIC of GalNAcS and GlcA-GalNAcS terminated structures. The experiments were repeated three times. Each time, independent GAG preparations from paw/ankle and knee/elbow joints of BALB/c mice and two additional murine strains, (B6xNOD)F1 and K/BxN, were used. The reported structural differences between paw/ankle GAGs to knee/elbow GAGs were constant in every instance.

CS Structures from Mouse Paws/Ankles and Knees/Elbows Are Different—Traditionally, GAG repeating disaccharide composition, linkage hexasaccharides, and reducing and non-reducing end sugar structures have to be isolated and analyzed individually. Our lab has adopted and developed a capillary HPLC-coupled mass spectrometry (capillary HPLC/MS) method that allows us to collect multiple GAG structural information by both UV and MS detection.

To understand the molecular basis of the binding affinity differences, GAGs isolated from paw/ankle and knee/elbow joints were digested with chondroitinase ABC that generated various mono-, di-, tri, tetra-, and GAG linkage hexasaccharides. Different sugars were separated by a capillary HPLC column. Chondroitinase ABC generated a double bond at uronic residues of repeating disaccharides as well as at uronic residues of all linkage hexasaccharides, which produced a UV absorbance at 232 nm. All sugar ions either with UV or non-UV absorbance were objectively detected by MS, which generated a TIC chromatogram (Fig. 4A). The summed UV signal from the chromatograms of all the disaccharides divided by the UV signal of the linkage hexasaccharide allowed a rough estimate of average chain length. Based on the UV signal, paw/ankle CS had 21 saccharides per CS chain, whereas knee/elbow CS had 40 saccharides per CS chain. Fig. 4B shows the extracted ion current of non-, mono-, di-, and trisulfated disaccharides from TIC shown in Fig. 4A. Disulfated disaccharides ([M - 2H]2- 268.5) in paw/ankle CS were 9% versus 4% in knee/elbow CS. Trisulfated disaccharides (m/z 747) were only observed in paw/ankle CS. The left panel of Fig. 4C shows the extracted IC of mono-, di-, and trisulfated CS linkage hexasaccharides (Hexa 1S, Hexa 2S, and Hexa 3S). Paw/ankle CS had increased mono- and trisulfated linkage hexasaccharides (Fig. 4C, left panel). More importantly, ∼4-fold more nonreducing end GlcA was observed in CS from paw/ankle (Fig. 4C, right panel) in which two nonreducing end ions (GalNAc 1S and GlcA-GalNAc 1S) were extracted from the TIC shown in Fig. 4A. The capillary HPLC/MS data shown in Fig. 4 indicated that the building blocks of CS from paw/ankle were different from those of knee/elbow. Particularly, the terminal saccharide is more often GlcA in paws than in knees, which correlates with the observed disease severity.

Nonreducing End GlcA Residue in GAGs Contributes to High Affinity GPI/GAG Interaction—The structural analysis indicated that paws/ankles CS had shorter, highly charged, and more GlcA terminated chains than CS from knees/elbows. This suggested that GPI binding might involve a CS terminal GlcA residue, which has a similar structure to the natural substrate of GPI, glucose 6-phosphate. To test this, we incubated aliquots of paw/ankle and knee/elbow GAG preparations with or without β-glucuronidase in digestion buffer to assess the effects on GPI binding (Fig. 5). The cleavage of terminal GlcA residues from GAGs by β-glucuronidase abrogates binding of GPI. This result indicated GAG GlcA terminals were involved in GPI binding.

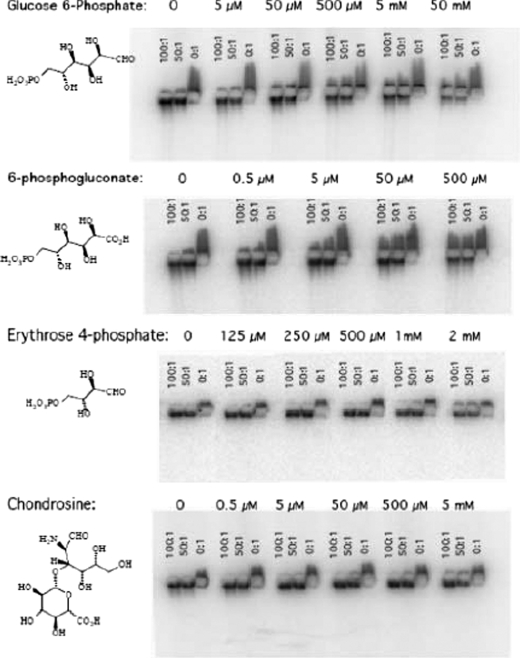

GPI/GAG Interactions Are Disrupted by GPI Substrates, Inhibitors, and GlcA Terminated Disaccharide—The evidence that GAG GlcA terminals participate in GPI binding supports the notion that the enzyme active site is involved in the interaction. To directly test active site involvement, we tested whether GPI substrates or inhibitors could perturb the effect of paw/ankle GAGs on the gel mobility of 125I-GPI. We examined the effect of the substrate glucose 6-phosphate and two competitive inhibitors of GPI enzymatic activity that are naturally occurring metabolites of the pentose phosphate pathway, 6-phosphogluconate, and erythrose 4-phosphate. Paws/ankle GAG:GPI ratios of 100:1, 50:1, and 0:1 were tested for all the compounds at different concentrations. Fig. 6 shows that all of these compounds interfere, in a concentration-dependent fashion, with the GPI/GAG gel mobility. The intensity of 50:1 GAG: GPI lanes for all the compounds at each concentration was quantified. Compared with control, the signals in the presence of glucose 6-phosphate was 74% at 50 μm, 66% at 500 μm, 63% at 5 mm, and 41% at 50 mm. In contrast, 50 and 500 μm 6-phosphogluconate produced attenuated signals of 71 and 53%, respectively. Erythrose 4-phosphate (Ery-4-P), which is a more potent inhibitor of GPI enzymatic activity than 6-phosphogluconate (19), did not affect the gel migration of GPI except at millimolar concentrations; 1 and 2 mm resulted in signals that were 88 and 63% of the control value. The results suggests that GAG displacement from GPI is not because of simple occupancy of the active site.

FIGURE 6.

A GPI substrate, two different GPI inhibitors, and a GlcA containing disaccharide interfere with GPI/GAG interactions. Across the top of each row, the concentrations of small molecules (left column) tested for their ability to disrupt GPI/GAG interaction are listed. Each lane contained 50 nm 125I-GPI and 50 × (100, 50, 0) nm of galactosamine equivalent GAGs from paws/ankles. Each compound was assayed at least twice.

Our data support the hypothesis that joint differences in GPI binding are because of the relative abundance of nonreducing GAG GlcA terminals that bind near the GPI active site. We next determined if a disaccharide with GlcA at the non-reducing end could compete with the binding of paw/ankle GAGs to GPI and, consequently, decrease the gel mobility of 125I-GPI. We chose chondrosine (GlcA-GalN), which is the disaccharide subunit of chondroitin sulfate lacking both sulfate and N-acetylation. Fig. 6, bottom panel, shows that chondrosine did not interfere except at 5 mm, the highest concentration tested. Quantification of the 50:1 GAG:GPI lanes revealed that 5 mm chondrosine decreased the cathodal signal to 74% of the control value. In a similar test, 5 mm GlcA had no effect (not shown). Thus a disaccharide may be the smallest sugar capable of GPI binding. Sugar linkage, sulfation of GalNAc residues, and/or longer saccharides are likely necessary for high affinity binding.

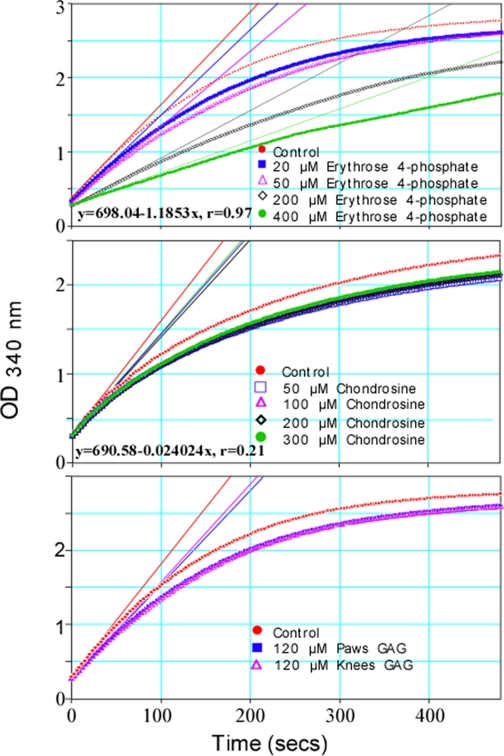

GPI/GAG Interaction Partially Involves GPI Catalytic Site—Because the effect of GAGs on GPI gel mobility was perturbed by several ligands that are known to bind the enzyme active site (Fig. 6), it seemed likely that GAG binding was affecting the conformation of the enzyme active site. Therefore, we tested the ability of GAGs to inhibit GPI enzymatic activity. To establish a competitive inhibition assay, we tested the effect of the competitive inhibitor Ery-4-P (Fig. 7, top panel). Vmax values (milli-OD units/min), calculated from the initial slopes of NADPH appearance during the first few seconds of the coupled reactions decreased from a control value of 759.5 to 693.6 (20 μm Ery-4-P), 662.2 (50 μm Ery-4-P), 383.4 (200 μm Ery-4-P), and 258.8 (400 μm Ery-4-P) with increasing concentrations of inhibitor. The decline of GPI activity with increasing Ery-4-P concentration is linear (y = 698.04 - 1.1853x, r = 0.97). In contrast, chondrosine inhibits GPI activity in a distinctly nonlinear way (y = 690.58 - 0.024204, r = 0.21) (Fig. 7, middle). At 300 μm, chondrosine decreases Vmax from a control value of 780.6 to 693.8. This inhibition is similar to the Vmax of 696.2 produced by the lowest concentration of chondrosine (50 μm). This insensitivity to increasing concentrations of inhibitor is the hallmark of partial inhibition, where an enzyme can bind substrate and make and release product even when it is saturated by an inhibitor. Fig. 7, bottom panel, compares the effect of paw/ankle GAGs to knee/elbow GAGs on the velocity of the reaction catalyzed by GPI. The GAGs, at the same concentration (120 μm), inhibited the reaction to the same extent. Paw/ankle GAGs reduce Vmax from 913.8 to 776.6 and knee/elbow GAGs reduce Vmax to 791.4. The similar GPI inhibitory ability but different GPI binding affinity suggest paw/ankle and knee/elbow GAG-GPI interactions engage only part of the enzyme active site.

FIGURE 7.

GAGs from paw/ankle or knee/elbow were partial inhibitors of enzymatic activity of GPI. Each well contained 4.2 units/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 1.0 mm NADP, 0.4 μg/ml (6.3 μm) recombinant mouse GPI, and inhibitors at various concentrations in 50 mm Tris, 88 mm KCl, pH 8.0. After equilibration at 37 °C, the reactions were initiated by the addition of 20 μl of fructose 6-phosphate for a final concentration of 2 mm. Absorbances were read every 3 s during an 8-min run. Vmax values were estimated using Softmax Pro 4.6, the application software for collecting and analyzing SpectraMax M2 data. The experiment was repeated three times.

DISCUSSION

In our efforts to understand the differences in the efficacy of GPI binding by paw/ankle versus knee/elbow GAGs, we have discovered that GPI is a GAG-binding protein with relatively high affinity. Many proteins, including DNA, RNA, and phospholipid-binding proteins, also bind to GAGs (20). Because RA is a heterogeneous disease with many autoantigens (21), our finding raises the possibility that other autoantigens could also be bound to the joint GAGs and participate in joint-specific inflammation.

GAGs are functionally important components of all synovial joints. They are found in the lining of the synovial capsule, where CS-4-O- and CS-6-O-sulfates are associated with the proteoglycans biglycan and decorin and where the keratan sulfate proteoglycan fibromodulin is found. They are indispensable components of this synovium, which acts as a permeability barrier for maintaining the integrity of synovial fluid (22–24). GAGs are also an essential part of the articular cartilage on the opposing surfaces of the bones of the joint. This cartilage is extracellular matrix formed by chondrocytes that are interspersed throughout. It is composed of collagen fibrils, hyaluronic acid, and the major proteoglycan, aggrecan. Articular cartilage has high water content but is a relatively impermeable network because of its many GAG chains (25, 26). Based on the anatomy of the articular cartilage of joints, it is clear that GAGs are abundantly expressed in all layers of cartilage. Because the generation of a GlcA nonreducing terminal is a relatively simple GAG modification, it seems plausible that GPI-binding sites should be available throughout cartilage, and this availability may be the reason GPI is an effective RA autoantigen.

The knee joint contains two layers (in distal femur and proximal tibia) of growth plate, as well as fibro-cartilagenous menisci, whereas the ankle joint contains one rudimentary growth plate in the distal tibia and no meniscus. The joints used in our studies were from 6- to 8-week-old mice. At this age, the growth plates are very thin. However, knee/elbow extracts could contain larger amounts of CS from the meniscus compared with ankle/paw extracts. Because we isolated GAGs from a whole joint homogenate, we cannot be certain that the GAGs that are active in our gel mobility, and GPI activity assays are the GAGs that are normally present on the articular surface of the joints. However, GAG-dependent cell surface and cartilage surface binding (Figs. 2 and 3) suggest that GAG is a receptor for GPI.

Screening for the presence of autoantibodies (e.g. rheumatoid factors) is commonly used as a diagnostic marker for human RA. Depending on the screening assay, αGPI antibodies are found in the serum of 15–64% RA patients (27, 28), and they are significantly elevated in patients afflicted with several types of inflammatory arthritis (27, 29), including arthritis caused by trauma and crystal deposits (27). αGPI antibodies are less frequently found in the serum of normal patients (30). In synovial fluid, where αGPI antibody concentrations are higher than in serum, patients with inflammatory arthritis with an immune origin (e.g. RA, Reiter's syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus), have higher αGPI levels than do patients with nonimmune inflammatory arthritis (27). Therefore, GPI is one of the autoantigens related to human inflammatory arthritis.

Cytoplasmic GPI catalyzes the reversible isomerization of glucose 6-phosphate and fructose 6-phosphate. This is required for glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the pentose phosphate pathway as well as protein and lipid glycosylation reactions. Based on co-crystal structures of GPI, substrates, or inhibitors, GPI/ligand interaction primarily affects the conformation of the relatively compact GPI active site. There are similarities between GPI interaction with the neuroleukin receptor and our findings of GPI binding to joint GAGs. In both instances, there is clear evidence of the involvement of the active site, as reflected by the dampening effect of enzyme inhibitors (31). Also for both instances, there is evidence that binding involves areas outside the active site.

The GAG that binds GPI involves a GlcA terminal. The comparatively low potency of chondrosine suggests that the active GAG is likely to be a longer polysaccharide and/or require further modification such as sulfation for high affinity GPI binding. This is supported by the structural differences observed in paw/ankle and knee/elbow GAGs (Fig. 4). We do not know whether the increased GlcA terminals in paw/ankle relative to knee/elbow are because of joint differences in de novo GAG synthesis or differential expression of extracellular enzymes that degrade GAGs, such as hexosaminidase (32). Elucidation of GAG biosynthesis and the structural motif that tethers GPI to joint surfaces should provide further insight into the nature and regulation of the GPI/GAG interaction.

Virtually every condition reported to decrease the incidence or the symptoms of RA is associated with increased glucose 6-phosphate or β-glucuronidase levels, including gout (33, 34), pregnancy (35–39), fasting (40, 41), insulin hypoglycemia (42–44), schizophrenia (45–48), AIDS (49–51), and Alzheimer disease (52–54). Perturbation of glucose 6-phosphate levels could affect the amount of GPI committed to extracellular release, or affect the amount of substrate or endogenous inhibitors of GPI co-secreted with the enzyme. In either case, GPI extracellular interactions would be modulated. Increased levels of serum β-glucuronidase are likely to parallel the increased β-glucuronidase activity in joints. This would lead to a reduction of GAGs with nonreducing ends terminating in GlcA, decreased joint binding of GPI, and decreased joint inflammation because of inhibition of the autoimmune response.

Overall, our studies revealed how a cytoplasmic autoantigen is bound to the cartilage surface in a joint. The heterogeneity in GAGs and different GAG/GPI interactions partially explain why some joints in arthritis are more affected than others and suggests that GAGs may be the receptors for other autoantigens involved in joint-specific inflammatory responses.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM069968 (to L. Z.) and AI031238 (to P. M. A.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: RA, rheumatoid arthritis; GPI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; Ab, antibodies; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; HS, heparan sulfate; CS, chondroitin sulfate; GalN, galactosamine; Ery-4-P, erythrose 4-phosphate; Fru-6-P, fructose 6-phosphate; MS, mass spectrometry; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; IC, ion current; TIC, total IC; CS, chondroitin sulfate; HS, heparan sulfate; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; BSA, bovine serum albumin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TEMED, N,N,′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine.

References

- 1.Matsumoto, I., Staub, A., Benoist, C., and Mathis, D. (1999) Science 286 1732-1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wipke, B. T., Wang, Z., Nagengast, W., Reichert, D. E., and Allen, P. M. (2004) J. Immunol. 172 7694-7702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandik-Nayak, L., Wipke, B. T., Shih, F. F., Unanue, E. R., and Allen, P. M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 14368-14373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji, H., Gauguier, D., Ohmura, K., Gonzalez, A., Duchatelle, V., Danoy, P., Garchon, H. J., Degott, C., Lathrop, M., Benoist, C., and Mathis, D. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194 321-330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wipke, B. T., Wang, Z., Kim, J., McCarthy, T. J., and Allen, P. M. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3 366-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto, I., Maccioni, M., Lee, D. M., Maurice, M., Simmons, B., Brenner, M., Mathis, D., and Benoist, C. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3 360-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esko, J. D., and Selleck, S. B. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71 435-471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esko, J. D., and Lindahl, U. (2001) J. Clin. Investig. 108 169-173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Studelska, D. R., Giljum, K., McDowell, L. M., and Zhang, L. (2006) Glycobiology 16 65-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu, Z. L., Zhang, L., Beeler, D. L., Kuberan, B., and Rosenberg, R. D. (2002) FASEB J. 16 539-545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahana, S. E., Lowry, O. H., Schulz, D. W., Passonneau, J. V., and Crawford, E. J. (1960) J. Biol. Chem. 235 2178-2184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, M. K., and Lander, A. D. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88 2768-2772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu, Z. L., Zhang, L., Yabe, T., Kuberan, B., Beeler, D. L., Love, A., and Rosenberg, R. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 17121-17129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esko, J. D., Stewart, T. E., and Taylor, W. H. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82 3197-3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avirutnan, P., Zhang, L., Punyadee, N., Manuyakorn, A., Puttikhunt, C., Kasinrerk, W., Malasit, P., Atkinson, J. P., and Diamond, M. S. (2007) PLoS Pathog. 3 e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, L., Lawrence, R., Frazier, B. A., and Esko, J. D. (2006) Methods Enzymol. 416, 205-221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avirutnan, P., Zhang, L., Punyadee, N., Manuyakorn, A., Puttikhunt, C., Kasinrerk, W., Malasit, P., Atkinson, J. P., and Diamond, M. S. (2007) PLoS Pathog. 3 e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence, R., Lu, H., Rosenberg, R. D., Esko, J. D., and Zhang, L. (2008) Nat. Meth. 5 291-292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell, E. E., and Schray, K. J. (1981) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 37 101-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conrad, H. E. (1998) Heparin-binding Proteins, Academic Press, San Diego

- 21.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist, S. (2005) Scand. J. Rheumatol. 34 83-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman, P. J., Scott, D., Abiona, A., Ashhurst, D. E., Mason, R. M., and Levick, J. R. (1998) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 509, 695-710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kavanagh, E., and Ashhurst, D. E. (1999) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 47 1603-1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman, P., Kavanagh, E., Mason, R. M., Levick, J. R., and Ashhurst, D. E. (1998) Histochem. J. 30 519-524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snowden, J. M., and Maroudas, A. (1976) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 428 726-740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maroudas, A. (1976) J. Anat. 122 335-347 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaller, M., Stohl, W., Tan, S. M., Benoit, V. M., Hilbert, D. M., and Ditzel, H. J. (2005) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64 743-749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaller, M., Burton, D. R., and Ditzel, H. J. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2 746-753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto, I., Lee, D. M., Goldbach-Mansky, R., Sumida, T., Hitchon, C. A., Schur, P. H., Anderson, R. J., Coblyn, J. S., Weinblatt, M. E., Brenner, M., Duclos, B., Pasquali, J. L., El-Gabalawy, H., Mathis, D., and Benoist, C. (2003) Arthritis Rheum. 48 944-954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto, I., Zhang, H., Muraki, Y., Hayashi, T., Yasukochi, T., Kori, Y., Goto, D., Ito, S., Tsutsumi, A., and Sumida, T. (2005) Arthritis Res. Ther. 7 R1183-R1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe, H., Takehana, K., Date, M., Shinozaki, T., and Raz, A. (1996) Cancer Res. 56 2960-2963 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, J., Shikhman, A. R., Lotz, M. K., and Wong, C. H. (2001) Chem. Biol. 8 701-711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godfrey, R. G. (2000) Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 18 649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vuorinen-Markkola, H., and Yki-Jarvinen, H. (1994) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 78 25-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spector, T. D., and Da Silva, J. A. (1992) Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 28 222-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett, J. H., Brennan, P., Fiddler, M., and Silman, A. J. (1999) Arthritis Rheum. 42 1219-1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills, J. L., Jovanovic, L., Knopp, R., Aarons, J., Conley, M., Park, E., Lee, Y. J., Holmes, L., Simpson, J. L., and Metzger, B. (1998) Metabolism 47 1140-1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrara, M., Mizrahy, O., Saposhnik, A., and Feinstein, G. (1979) Isr. J. Med. Sci. 15 746-748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpintero, A., Sanchez-Martin, M. M., Cabezas-Delamare, M. J., and Cabezas, J. A. (1996) Clin. Chim. Acta 255 153-164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skoldstam, L., and Magnusson, K. E. (1991) Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 17 363-371 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmblad, J., Hafstrom, I., and Ringertz, B. (1991) Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 17 351-362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weitzner, H. A., and Snowden, V. L. (1952) Perm. Found. Med. Bull. 10 119-128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haydu, G. G. (1950) Rheumatism 6 133-136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svenson, K. L., Pollare, T., Lithell, H., and Hallgren, R. (1988) Metabolism 37 125-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oken, R. J., and Schulzer, M. (1999) Schizophr. Bull. 25 625-638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gorwood, P., Pouchot, J., Vinceneux, P., Puechal, X., Flipo, R. M., De Bandt, M., and Ades, J. (2004) Schizophr. Res. 66 21-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stone, W. S., Faraone, S. V., Su, J., Tarbox, S. I., Van Eerdewegh, P., and Tsuang, M. T. (2004) Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 127 5-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurup, R. K. A., Devi, D., Augustine, J., and Kurup, P. A. (2001) Neurosci. Res. Commun. 28 95-106 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bijlsma, J. W., Derksen, R. W., Huber-Bruning, O., and Borleffs, J. C. (1988) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 47 350-351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerr, L. D., and Spiera, H. (1991) J. Rheumatol. 18 1739-1740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saha, A. K., Glew, R. H., Kotler, D. P., and Omene, J. A. (1991) Clin. Chim. Acta 199 311-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jenkinson, M. L., Bliss, M. R., Brain, A. T., and Scott, D. L. (1989) Br. J. Rheumatol. 28 86-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGeer, P. L., Schulzer, M., and McGeer, E. G. (1996) Neurology 47 425-432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazzola, J. L., and Sirover, M. A. (2003) J. Neurosci. Res. 71 279-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]