Abstract

Sulfite dehydrogenases (SDHs) catalyze the oxidation and detoxification of sulfite to sulfate, a reaction critical to all forms of life. Sulfite-oxidizing enzymes contain three conserved active site amino acids (Arg-55, His-57, and Tyr-236) that are crucial for catalytic competency. Here we have studied the kinetic and structural effects of two novel and one previously reported substitution (R55M, H57A, Y236F) in these residues on SDH catalysis. Both Arg-55 and His-57 were found to have key roles in substrate binding. An R55M substitution increased Km(sulfite)(app) by 2–3 orders of magnitude, whereas His-57 was required for maintaining a high substrate affinity at low pH when the imidazole ring is fully protonated. This effect may be mediated by interactions of His-57 with Arg-55 that stabilize the position of the Arg-55 side chain or, alternatively, may reflect changes in the protonation state of sulfite. Unlike what is seen for SDHWT and SDHY236F, the catalytic turnover rates of SDHR55M and SDHH57A are relatively insensitive to pH (∼60 and 200 s–1, respectively). On the structural level, striking kinetic effects appeared to correlate with disorder (in SDHH57A and SDHY236F) or absence of Arg-55 (SDHR55M), suggesting that Arg-55 and the hydrogen bonding interactions it engages in are crucial for substrate binding and catalysis. The structure of SDHR55M has sulfate bound at the active site, a fact that coincides with a significant increase in the inhibitory effect of sulfate in SDHR55M. Thus, Arg-55 also appears to be involved in enabling discrimination between the substrate and product in SDH.

Sulfite-oxidizing enzymes protect cells against potentially fatal damage to DNA and proteins caused by exposure to sulfite, and consequently they are found in all forms of life (1). In bacteria, sulfite oxidation is often linked to energy-generating processes during chemolithotrophic growth on reduced sulfur compounds (2, 3), whereas both plant and vertebrate sulfite oxidases have been shown to detoxify sulfite arising from the degradation of methionine and cysteine and exposure to sulfur dioxide (4, 5).

All known sulfite-oxidizing enzymes belong to the same family of mononuclear molybdenum enzymes. Their active sites contain one molybdopterin unit per molybdenum atom, and these enzymes may also contain heme groups as accessory redox centers (6–9). Examples of different types of sulfite-oxidizing molybdoenzymes are the homodimeric plant sulfite oxidase, which does not contain a heme group and uses oxygen as its preferred electron acceptor (9), the homodimeric chicken and human liver sulfite oxidases (CSO3 and HSO, respectively) (10), which are also able to use oxygen as an electron acceptor, and the bacterial sulfite dehydrogenase (SDH) isolated from the soil bacterium Starkeya novella (11, 12), which cannot donate electrons directly to oxygen. Each monomer of CSO and HSO contains a heme b center in addition to the molybdenum center, and the redox centers are located within separate, flexibly linked domains of the same protein subunit. In contrast, the bacterial enzyme is a heterodimer where each subunit of the enzyme contains one redox center. The molybdopterin cofactor is located in the larger 40.2-kDa SorA subunit, and the c-type heme is located in the smaller, 8.8-kDa SorB subunit (12). The SDH quaternary structure thus differs clearly from that of the human and chicken sulfite oxidases.

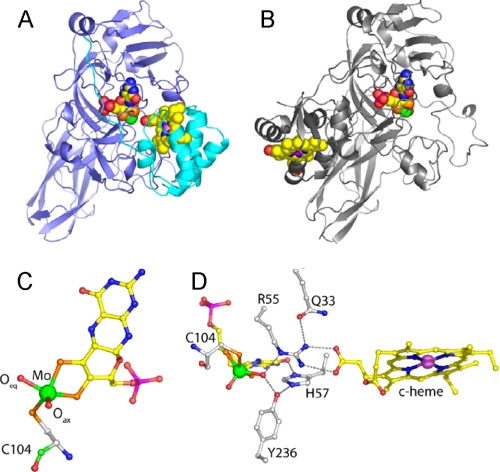

Crystal structures are available for plant sulfite oxidase, CSO, and the bacterial SDH (10, 11, 13–15) and have revealed molecular details of the sulfite-oxidizing enzymes. In the CSO structure, the mobile heme b domain occupies a position too removed from the molybdenum active site to mediate efficient electron transfer (10), and indeed the kinetics of this enzyme are known to be complicated by domain movements (16). In contrast, the bacterial SDH is a tight complex with strong electrostatic interactions between the subunits, and the close approach of the redox centers (Mo–Fe distance 16.6 Å) allows for rapid electron transfer (11, 17) (Fig. 1, A and B).

FIGURE 1.

Details of the crystal structure of wild type SDH and comparison with CSO. A, ribbon diagram of the SDH heterodimer with the SorA and SorB subunits colored blue and cyan, respectively, and the redox cofactors in space-filling mode with the molybdenum atom colored green and the iron atom colored violet. B, ribbon diagram of a single subunit of CSO with the molybdopterin binding domain in the same orientation as SorA in A. The cytochrome domain of CSO is clearly in a different position with respect to the molybdenum cofactor than is seen for the cytochrome subunit of SDH. C, SDH molybdopterin cofactor demonstrating the geometry of the molybdenum ligands. The thiol ligands donated by the organic component of molybdopterin and the Cys-104 side chain, and the reactive oxygen ligand (Oeq) sit in the equatorial plane with the axial oxygen (Oax) ligand at the apex of a square pyramid. Atoms are colored as follows: molybdenum (green), sulfur (orange), phosphorous (magenta), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue), and carbon (yellow in the cofactor and white in the protein). D, hydrogen bonding network around the substrate binding site. The molybdopterin and heme cofactors are shown together with active site residues Cys-104, Arg-55, His-57, Tyr-236, and Gln-33. Figs. 1 and 4 were prepared using Pymol (37).

Despite the overall structural differences of these proteins, the coordination geometries of the molybdenum active sites of these sulfite-oxidizing enzymes are nearly identical. The oxidized molybdenum center has a square pyramidal conformation, with three sulfur and two oxo ligands (18). Within this molybdenum center, the equatorial oxo ligand is proposed to be catalytically active, whereas the axial oxo ligand is not thought to participate directly in the reaction (Fig. 1C). During catalysis, the equatorial oxo ligand is transformed into a hydroxy/water ligand as a result of the reduction of the molybdenum center (Fig. 2), and it is in this form that it is generally observed in the CSO and SDH crystal structures.

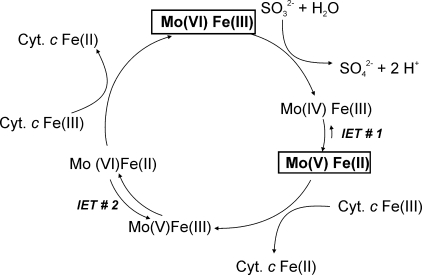

FIGURE 2.

Proposed reaction mechanism for S. novella sulfite dehydrogenase. The reaction is shown in terms of the redox states of the molybdenum and heme centers present in the enzyme. Shown in boldface type and boxed are the stable redox states of the S. novella SDH. Cyt. c, a mitochondrial type cytochrome c550 (e.g. horse heart or S. novella cytochrome c550) that can act as the external electron acceptor.

SDH, CSO, and HSO show similarly high affinities for their substrate, sulfite, and several highly conserved residues surround the substrate-binding and molybdenum active site, namely Tyr-236 (all residues given in SDH numbering (11)), Arg-55, and His-57 (Fig. 1D). Both Arg-55 and Tyr-236 form hydrogen bonds to the catalytically active equatorial Mo-oxo group, whereas His-57 is positioned close to both Arg-55 and Tyr-236 (10, 11) (Fig. 1D). In addition, the crystal structure of the bacterial SDH shows that Arg-55 interacts directly with the second SDH redox center by hydrogen bonding to heme propionate-6 (Fig. 1D) (11).

As a result of the similarities in catalytic parameters and the structure of the active site, the bacterial SDH is a very good system for studies of enzymatic sulfite oxidation and especially the molecular basis for catalysis. Since this enzyme does not rely on domain movement for catalysis, it has a less complicated reaction mechanism than the vertebrate enzymes, which facilitates the interpretation of kinetic data, and it can be readily crystallized with both redox centers present in an electron transfer competent conformation. We have previously reported data on the structure, kinetics, EPR, and redox properties of a Y236F-substituted SDH (13). In addition to reduced turnover and substrate affinity, this substitution influences the reactivity of the SDH toward oxygen, turning SDHY236F essentially into an (albeit weak) sulfite oxidase. In order to further understand the roles of the conserved amino acids surrounding the molybdenum active site of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes, we have created two novel amino acid substitutions in the Arg-55 and His-57 residues present at the active site and have investigated their effect on catalytic and spectroscopic parameters of the bacterial SDH. We have also solved the crystal structures of the substituted enzymes, which have provided new insights into the conformation and plasticity of the active site of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes and how the conserved active site residues contribute to sulfite oxidation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology—Standard methods were used throughout (19). The amino acid substitutions were created using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions and the pSorex plasmid (20) as the mutagenesis template. Primers R55Mf (gac gcc ttc ttc gtg atg tac cat ctc gcc ggt), R55Mr (acc ggc gag atg gta cat cac gaa gaa ggc gtc), H57Af (ttc ttc gtg cgc tac gcc ctc gcc ggt ata ccg), and H57Ar (cgg tat acc ggc gag ggc gta gcg cac gaa gaa) were used to create an Arg-55 → Met and the His-57 → Ala substitution as described in Ref. 13. The presence of the substitutions in the plasmids pSorex-R55M and pSorex-H57A was confirmed by DNA sequencing, followed by subcloning of the expression construct into pRK415 as described in Ref. 20. The pRK415-based expression constructs pRK-sorexR55M and pRK-sorexH57A were transferred into Rhodobacter capsulatus 37B4 ΔdorA (21) by conjugation as in Ref. 20. Following conjugation, the expression plasmids were extracted from R. capsulatus, and the mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Protein Purification and Characterization—Recombinant protein was produced and purified as in Ref. 11. Metal analysis was performed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry at the Acquire Center and the National Center for Environmental Toxicology, both at the University of Queensland. Protein determinations were carried out using the 2D Quant kit (GE Healthcare) or the BCA protein determination kit (BCA-1; Sigma), and polyacrylamide gels were prepared according to Ref. 22. Oxygen reoxidation experiments were carried out as described in Ref. 13.

Crystallization and Solution of the SorABR55M and SorH57A Crystal Structures—Recombinant SDHR55M and SDHH57A were crystallized as previously described from 2.2 m ammonium sulfate, 2% polyethylene glycol 200, 1 m HEPES, pH 7.4 (11), and crystals were cryocooled to 100 K within 5 days of setting up crystallization trials. Data were collected on beam-line 10.1 of the SRS, Daresbury Laboratory. Data were processed and scaled using Mosflm/SCALA (23), and further analysis used programs from the CCP4 suite (24). The crystal structure was refined with the program REFMAC (25), using the SDHWT structure (11) (Protein Data Bank code 2BlF) as the starting point, and inspection of the model and electron density maps was carried out using the program O (26). Data collection, processing, and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1. The final models comprise residues 1–373 of the SorA subunit, residues 1–81 of the SorB subunit, one molybdenum cofactor (Moco), one c-type heme, one or two sulfate ions, and water molecules. The structures have good stereochemistry with 99.5% of the residues in the most favored and additionally allowed regions and no residues in disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, as defined by PROCHECK (27).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| R55M | H57A | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Beamline | SRS 10.1 | SRS 10.1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.074 | 1.074 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50-2.0 | 50-2.1 |

| Unique reflections | 34463 | 27649 |

| Completeness (%)a | 98.2 (89.1) | 93.0 (83.8) |

| Multiplicitya | 3.8 (2.7) | 3.4 (2.0) |

| I/s(I)a | 14.3 (3.8) | 10.6 (2.1) |

| Rmergeb (%)a | 9.5 (28.8) | 10.2 (41.8) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 30-2.0 | 20-2.1 |

| Rcrystc (%) | 16.3 | 14.7 |

| Rfreed (%) | 20.7 | 20.1 |

| Root mean square deviations from ideal geometry | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.016 | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.59 | 1.4 |

| No. of water molecules | 357 | 378 |

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shells of 2.07-2.0 Å and 2.21-2.1 Å.

Rmerge = ShSi|(Ihi - Ih)|/ShSi|(Ihi).

Rcryst = S|Fo - Fc|/ΣFo, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Rfree was calculated with 5% of the data that had been excluded from refinement.

For the SDHR55M structure, weighted difference Fourier maps calculated with coefficients mFo – DFc showed a strong negative peak on the molybdenum atom, which suggested that this atom is not fully occupied. This situation has already been observed for the SDHY236F structure (13), and the same procedure was used to estimate the molybdenum occupancy. The occupancy of the molybdenum was estimated at 50%. Further refinement with the molybdenum occupancy set appropriately resulted in a reasonable B-factor for this atom, similar to that of surrounding atoms, and no significant residual difference density. In the case of the SDHH57A structure, the molybdenum appears fully occupied.

Enzyme Assays—Routine enzyme assays were carried out at 25 °C using 20 mm Tris acetate buffer, pH 8, 2 mm sulfite, 0.04 mm cytochrome c (horse heart; catalog number C7752; Sigma) and a suitable amount of sulfite dehydrogenase (0.1–0.2 nmol, depending on the variant studied) (12, 13), using either a Hitachi UV3000 double beam spectrophotometer or a Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Varian). The reaction was started by the addition of sulfite, and the reduction of cytochrome c was monitored at 550 nm. Both sulfite and cytochrome c solutions were prepared fresh each day. Studies of enzyme stability as a function of pH were conducted by preincubating a concentrated sample of purified enzyme at the specified pH value. Samples were removed from these solutions at various time intervals, and enzyme activities were immediately determined using the standard assay at pH 8.0. The normal time scale of an SDH assay is between 90 and 120 s, the preincubation experiments were carried out for up to 15 min. For determination of Km(sulfite)(app) values, the amount of sulfite added to the assay was varied and sulfite concentrations between ∼0.2 and 10 Km were used. All assays were carried out in triplicate. Buffer systems used were 20 mm Bistris acetate (pH 6.0 and 6.5), 20 mm Tris acetate (pH 7.0–8.5), 20 mm glycine (pH 9.0–10.0), similar to the systems used in studies of CSO (28) and HSO (29), except for SDHR55M, where all buffers used were 20 mm Tris acetate. Very high concentrations of sulfite (>20 mm) were found to inhibit the SDH reaction. Kinetic constants were derived by direct nonlinear regression using SigmaPlot 9.0 (SysStat Inc.).

The effect of sulfate on SDH activity (SDHWT and SDHR55M) was investigated in two ways: 1) increasing amounts of sulfate were added to standard SDH assays, and the changes in reaction velocity observed; 2) to determine the effect of sulfate on Km(sulfite)(app) and kcat(app), these parameters were determined in the presence of 0, 10, 30, and 60 mm sodium sulfate, as described above.

Non-steady-state parameters for the reductive half-reaction of wild type and mutant SDH were determined on an SX18.MV Stopped Flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics) at 10 °C. The lowering of the temperature was necessary, since the kred(heme) values observed for the wild type enzyme were approaching the detection limits of the apparatus. Experiments were carried out using 20 mm buffers and a final concentration of 1.1 μm purified, oxidized sulfite dehydrogenase (except for SDHH57A, where a 0.4 μm enzyme solution was used), and the reaction was monitored at 418 nm. Sulfite concentrations were varied between 2.5 and 16,000 μm (final concentration) as appropriate for each enzyme used. Parameters for SDHY236F could not be determined, since this enzyme can be reoxidized by molecular oxygen, and accessories for anaerobic work were not available. Similarly, only a core data set could be determined for SDHH57A due to the scarcity of the protein. Kd(sulfite) and kred(heme) were determined by direct nonlinear fitting of the data.

EPR—EPR samples for SDHWT and SDHR55M were prepared in buffers containing 100 mm Bistris propane, pH 7.0, whereas the SDHH57A sample was prepared in 100 mm Bistris (pH 5.8). The pH of the buffer was adjusted using NaOH or acetic acid to give the required pH. Approximately 1 mg of protein was reduced with a 20-fold excess of sodium sulfite and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The continuous wave EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker ESP-300E spectrometer at 77 K using the experimental parameters given in the legend for Fig. 4. Pulsed electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) experiments were performed on a home-built Ka-band (26–40 GHz) pulsed EPR spectrometer (30).

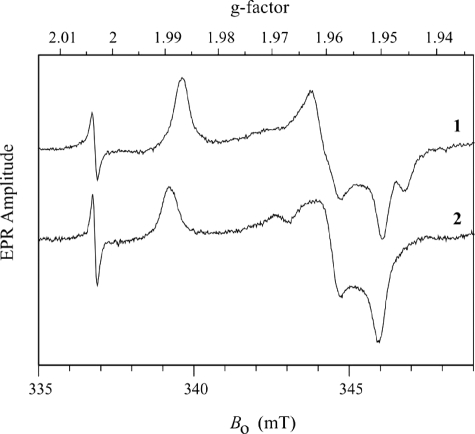

FIGURE 4.

Continuous wave EPR spectra of SDH forms. Trace 1, SDHH57A at pH 5.8; trace 2, SDHR55M at pH 7.0. Experimental conditions were as follows: νmw = 9.444 GHz; modulation amplitude = 0.1 millitesla; microwave power = 0.2 milliwatt; temperature = 77 K. The narrow line at g = 2.0036 is the signal of the DPPH standard.

RESULTS

Catalytic Properties of the Wild Type Sulfite Dehydrogenase—To date, only catalytic parameters determined at pH 8 and pH 6 have been reported for SDHWT (13). In order to be able to fully assess the impact of substitutions of active site amino acids on the SDH-catalyzed reaction (Fig. 2), we first determined a complete set of Km(sulfite)(app) and kcat(app) values for SDHWT between pH 6 and 10 (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of the SorAB sulfite dehydrogenase (SDHWT) from S. novella

| pH | Km(sulfite) | kcat | kcat/Km(sulfite) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm | s-1 | m-1 s-1 | |

| 6.0 | 0.6 × 10-3 ± 9.5 × 10-5 | 63.5 ± 2.2 | 1.06 × 108 |

| 6.5 | 1.1 × 10-3 ± 0.14 × 10-3 | 86.2 ± 2.2 | 7.55 × 107 |

| 7.0 | 3.7 × 10-3 ± 0.45 × 10-3 | 158.8 ± 4.5 | 4.27 × 107 |

| 7.5 | 7.1 × 10-3 ± 0.82 × 10-3 | 293.4 ± 7 | 4.03 × 107 |

| 8.0 | 2.2 × 10-2 ± 0.26 × 10-2 | 345.3 ± 11 | 1.53 × 107 |

| 8.5 | 8.6 × 10-2 ± 0.85 × 10-2 | 410 ± 11 | 4.88 × 106 |

| 9.0 | 0.324 ± 0.029 | 519 ± 11 | 1.5 × 106 |

| 9.5 | 1.66 ± 0.18 | 431 ± 16 | 2.51 × 105 |

| 10.0 | 3.389 ± 0.44 | 23.7 ± 1.3 | 6.77 × 103 |

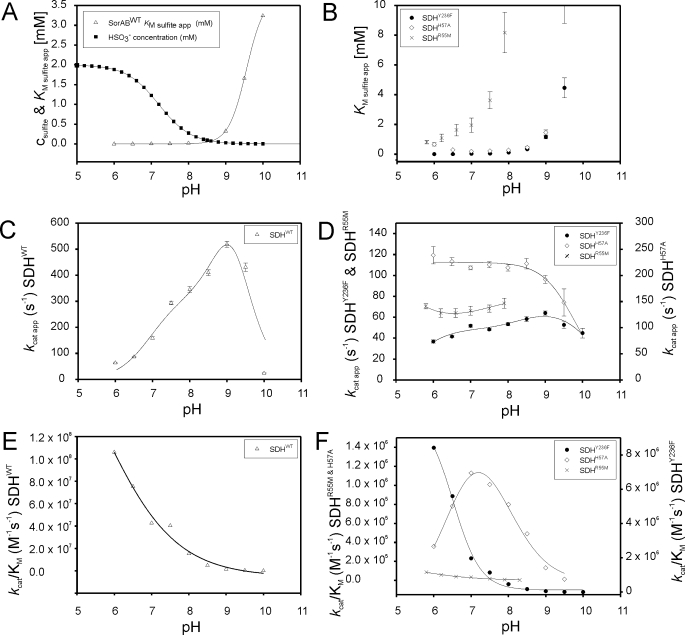

FIGURE 3.

Influence of pH on the kinetic parameters of SDHWT and its substituted forms. A, plot of Km(sulfite)(app) for SDHWT and sulfite speciation versus pH; B, plot of Km(sulfite)(app) versus pH for SDHR55M (×), SDHY236F (•), and SDHH57A (⋄); C, plot of kcat(app) versus pH for SDHWT; D, plot of kcat(app) versus pH for SDHR55M (×), SDHY236F (•), and SDHH57A (⋄); E, plot of kcat/Km(sulfite) versus pH SDHWT; F, plot of kcat/Km(sulfite) versus pH for SDHR55M (×), SDHY236F (•), and SDHH57A (⋄).

To ensure that observations made were not due to artifacts caused by inactivation of the sulfite dehydrogenase upon exposure to extreme pH values, the stability of the wild type and mutant enzymes was determined between pH 6 and 10 as a function of time. No significant loss of activity was observed (Table S1).

The apparent Km(sulfite) values for SDHWT decrease with decreasing pH to a value of 0.0006 mm at pH 6 and increase markedly above pH 8.5 to a maximum of 3.4 mm at pH 10. A similar behavior with strong increases of Km(sulfite)(app) above pH 8.5 has been reported for both CSO (Km(sulfite) 0.01–0.118 mm, pH 6–10) (28) and HSO (Km(sulfite) 0.0012–0.067 mm, pH 6–10) (29). The change in Km(sulfite)(app) seen in SDHWT at higher pH values, however, is more than 1 order of magnitude larger than that seen for the two vertebrate enzymes. This characteristic change in substrate affinity at higher pH has been suggested to be indicative of a preference of the enzyme for hydrogen sulfite (29), HSO–3, which has a pKa value of pH 7.2 (31). At pH 8.5 and higher, the protonated form of the substrate molecule can be expected to be present in only very small amounts (Fig. 3A).

The kcat(app) values for SDH increase up to pH 9.0 where a value of 519 ± 11 s–1 is reached, after which turnover numbers decline rapidly toward 23.7 ± 1.3 s–1 at pH 10 (Table 2 and Fig. 3C). CSO exhibits the same behavior with kcat(app) increasing up to 119 s–1 at pH 9.0 (28), however, HSO kcat(app) showed only a single pKa at low pH and reached a steady maximal value of ∼25 s–1 at pH 7.5 and higher (29).

The data in Table 2 were fitted to a bell-shaped profile as described in Ref. 13, and pKa values of pH 7.5 and pH 9.7 were derived. These pKa values are slightly different from previously reported values obtained under standard assay conditions (2 mm sulfite), where maximal SDH activity is observed at pH 8.0–8.5 with apparent pKa values of pH 7.6 and pH 9.4 (12, 13) (Fig. S1). The new data presented here clearly show that the strong increase in Km(sulfite)(app) above pH 8.5 shapes the activity profile and causes the apparent decrease in activity previously observed under standard conditions, since sulfite is no longer present in saturating concentrations.

As judged by the magnitude of the second order rate constants, SDH is a highly efficient enzyme that operates close to the limits imposed by substrate diffusion, with apparent kcat/Km(sulfite)(app) values in the range of 107 m–1 s–1 at pH 8.0 and below (Table 2 and Fig. 3E). Plots of kcat/Km(sulfite)(app) versus pH have an S-shaped profile with a pKa of pH 7.0 ± 0.14.

Catalytic Properties of Y236F-substituted Sulfite Dehydrogenase—Three crucial and strictly conserved residues, Tyr-236, Arg-55, and His-57, are found close to the molybdenum active site of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes and have been shown to interact with the molybdenum center (11, 13). Tyr-236 forms a hydrogen bond with the reactive equatorial oxo-group of the molybdenum center, an interaction that is disrupted by the Y236F substitution. We have previously reported catalytic parameters of SDHY236F at pH 6.0 and pH 8.0 (13). A full set of catalytic parameters for this enzyme is set out in Table 3. The Y236F substitution leads to an increase in Km(sulfite)(app) values by a factor of ∼5–7. Thus, Tyr-236 appears to have a moderate influence on substrate binding or the stability of the enzyme-substrate complex. This latter effect may also be mediated by changes in the ligand environment of the molybdenum center caused by the loss of the hydrogen bond between Tyr-236 and the equatorial molybdenum oxo-group, although our earlier study failed to show any changes in the molybdenum redox potential (13). For SDHY236F, the overall shape of the kcat(app) versus pH plot is similar to that seen for SDHWT, and the optimum pH for activity is pH 9.0 in both cases (Fig. 3D). However, in SDHY236F, kcat(app) is lowered to about 13% of the SDHWT activity between pH 7.5 and 9.5, with SDHY236F activities at the extremes of the pH scale being matched more closely to that of SDHWT. It therefore appears that in addition to its important role in regulating the activity of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes toward oxygen (13), Tyr-236 also affects enzyme turnover.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of substituted SorAB sulfite dehydrogenases, SDHY236F, SDHR55M, and SDHH57A

Square brackets denote values for which insufficient data points could be obtained due to the high sulfite concentrations needed to achieve saturating sulfite concentrations.

|

pH

|

Kinetic parameters

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Km(sulfite) | kcat | kcat/Km(sulfite) | |

| mm | s-1 | m-1 s-1 | |

| SDH Y236F | |||

| 6.0 | 0.004 ± 0.6 × 10-3 | 36.8 ± 1.5 | 8.42 × 106 |

| 6.5 | 0.007 ± 0.6 × 10-3 | 41.6 ± 0.8 | 5.60 × 106 |

| 7.0 | 0.026 ± 0.0032 | 51.8 ± 1.5 | 1.97 × 106 |

| 7.5 | 0.042 ± 0.0041 | 48.3 ± 1 | 1.14 × 106 |

| 8.0 | 0.114 ± 0.0135 | 53.4 ± 1.6 | 4.61 × 105 |

| 8.5 | 0.332 ± 0.0447 | 58.3 ± 2.4 | 1.73 × 105 |

| 9.0 | 1.155 ± 0.1166 | 64 ± 2 | 5.45 × 104 |

| 9.5 | 4.456 ± 0.6693 | 52.7 ± 3.5 | 1.16 × 104 |

| 10.0 | 15.487 ± 2.8 | 44.8 ± 4.7 | 2.84 × 103 |

| SDH R55M | |||

| 5.8 | 0.812 ± 0.114 | 70.5 ± 2.4 | 8.68 × 104 |

| 6.2 | 1.087 ± 0.26 | 64.0 ± 3.9 | 5.89 × 104 |

| 6.6 | 1.63 ± 0.39 | 64.0 ± 4.3 | 3.93 × 104 |

| 7.0 | 1.95 ± 0.49 | 66.3 ± 4.2 | 3.4 × 104 |

| 7.5 | 3.62 ± 0.57 | 68.3 ± 3.3 | 1.89 × 104 |

| 7.9 | 8.17 ± 1.37 | 73.4 ± 4.8 | 8.98 × 103 |

| 8.3 | [33.27 ± 7.5] | [109.88 ± 15.04] | [3.3 × 103] |

| SDH H57A | |||

| 6.0 | 0.667 ± 0.12 | 238.8 ± 16.5 | 3.58 × 105 |

| 6.5 | 0.29 ± 0.003 | 226.5 ± 7.6 | 7.82 × 105 |

| 7.0 | 0.189 ± 0.001 | 214.5 ± 3.7 | 1.13 × 106 |

| 7.5 | 0.22 ± 0.002 | 220.5 ± 5.6 | 1.01 × 106 |

| 8.0 | 0.27 ± 0.003 | 214.6 ± 6 | 7.99 × 105 |

| 8.5 | 0.452 ± 0.06 | 222.4 ± 9.9 | 4.92 × 105 |

| 9.0 | 1.46 ± 0.16 | 192.5 ± 7.5 | 1.32 × 105 |

| 9.5 | 12.2 ± 3.4 | 148.4 ± 25.8 | 1.22 × 104 |

Catalytic Properties of the R55M- and H57A-substituted Sulfite Dehydrogenases—In order to investigate the influence of the other two strictly conserved residues on SDH activity, we created substitutions in both Arg-55 and His-57. The molybdenum content of the two novel substituted proteins was determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. The molybdenum content of the SDHR55M was between 60 and 70%, whereas SDHH57A contained ∼75–83% molybdenum, both being indicative of a high proportion of active enzyme in the respective preparations. Since SDHR55M, like the previously described SDHY236F, carries a substitution very close to the molybdenum active site, we investigated whether the substitution of Arg-55 also leads to an increased reactivity toward oxygen. However, within experimental error, the air reoxidation rates for SDHR55M were the same as those determined for SDHWT (13).

In steady-state assays, the substitution of a Met residue for Arg-55 resulted in a variant SDH characterized by two key features (Table 3): an increase of Km(sulfite)(app) by 2–3 orders of magnitude relative to SDHWT and, interestingly, a nearly invariant value for kcat(app) (∼65 s–1) between pH 6 and pH 8. These results clearly point to an important role for Arg-55 in substrate binding and/or the stabilization of the enzyme-substrate complex as well as a role in shaping the characteristic SDH activity profile via influencing enzyme turnover.

The plot of Km(sulfite)(app) versus pH still shows the characteristic steep increase at higher pH values, previously observed for SDHWT and SDHY236F. However, we note that care should be taken in the interpretation of the higher pH catalytic data for SDHR55M, since these could not be reliably determined above pH 8 due to the large amounts of sulfite needed to saturate the reaction (around 10 mm at pH 6 and well over 35 mm at pH 8), as a result of the large values for Km(sulfite)(app). SDHR55M appears to gain activity at lower pH values when assayed under standard conditions with 2 mm sulfite present, resulting in an activity profile with a single apparent pKa and maximal activity at pH 6 or below (Fig. S1).

Compared with SDHR55M, the changes in the catalytic parameters seen following a H57A substitution were more subtle (Table 3). The kcat(app) values were found to be fairly constant over the pH range 6–9, although SDHH57A showed a higher level of activity at ∼200 s–1 than SDHY236F and SDHR55M over the pH ranges measured. Indeed, at pH 7 and below SDHH57A, kcat(app) rates are higher than those of the wild type enzyme.

Substitution of His-57 with alanine also lowers substrate affinity, as demonstrated by the increase in Km(sulfite)(app) values. The most notable observation, however, was that the pH profile for Km(sulfite)(app) reaches a minimum at pH 7 (0.189 ± 0.001 mm), and values increase clearly below that pH to a value of 0.667 ± 0.12 mm at pH 6. At pH 8 and above, Km(sulfite)(app) was increased slightly (by factors of ∼5–10) relative to SDHWT, indicating that although it is removed from the molybdenum center, His-57 has a role in substrate binding. None of the wild type and substituted sulfite-oxidizing enzymes (both SDH and CSO/HSO type) studied to date show a similar increase of Km(sulfite)(app) at low pH, making SDHH57A a unique target for further studies into catalysis in these enzymes. Our data suggest that the protonation of the His-57 residue (pKa ∼ 6.04) (32) at lower pH values may have a major role in maintaining the high affinity of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes for sulfite (or hydrogen sulfite) at pH values below 7.

Non-steady-state Parameters of the Reductive Half-reaction of SDH—pH-dependent changes in steady-state kinetic parameters may not always directly reflect a change in the molecular properties of the enzyme under study. To ascertain whether this was the case here, the non-steady-state parameters for the reductive half-reaction of SDHWT, SDHR55M, and SDHH57A were determined (Table 4 and Fig. S2). All experiments were carried out at 10 °C to keep reaction rates well within the specification of the instrument used.

TABLE 4.

Non-steady state kinetic parameters for the reductive half-reaction of the SDHWT and SDHR55M sulfite dehydrogenases

Data were collected at 418 nm and 10 °C. Square brackets denote values for which insufficient data points could be obtained due to the high sulfite concentrations needed to achieve saturating sulfite concentrations.

|

pH

|

Kinetic parameters

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kd(sulfite) | kred(heme) | kred(heme)/Kd(sulfite) | |

| mm | s-1 | m-1 s-1 | |

| SDH WT | |||

| 6 | 0.0032 ± 0.0003 | 730 ± 10 | 2.25 × 108 |

| 6.5 | 0.0036 ± 0.0002 | 847 ± 10 | 2.39 × 108 |

| 7 | 0.0014 ± 0.0001 | 782 ± 16 | 5.58 × 107 |

| 7.5 | 0.0031 ± 0.0003 | 677 ± 20 | 2.18 × 107 |

| 8 | 0.0087 ± 0.0007 | 776 ± 22 | 8.89 × 106 |

| 8.5 | 0.412 ± 0.029 | 829 ± 32 | 2.01 × 106 |

| 9 | 1.183 ± 0.094 | 731 ± 20 | 6.18 × 105 |

| 9.5 | 3.811 ± 0.75 | 674 ± 45 | 1.77 × 105 |

| SDH R55M | |||

| 5.5 | 4.53 ± 0.51 | 746 ± 34 | 1.65 × 105 |

| 6 | 6.48 ± 0.68 | 662 ± 31 | 1.02 × 105 |

| 7 | [22.8 ± 4.5] | [240 ± 32] | [1.05 × 104] |

For SDHWT Kd(sulfite) decreased with decreasing pH in the same way as the Km(sulfite)(app) values determined in steady-state assays. Overall, Kd(sulfite) values were slightly higher than the corresponding apparent Km(sulfite) values, which may be due to the different temperatures at which the assays were carried out (Table 4). In contrast, kred(heme), which reflects the SDH reaction rate up to the formation of the stable, Mo(V)Fe(II), the two-electron reduced form of SDH was nearly invariant with pH up to pH 9 at ∼740 s–1, which differs from the behavior observed for kcat but is similar to what has been reported for vertebrate sulfite oxidases (28, 29). As already pointed out for CSO (28), the difference in the behavior of kcat and kred(heme) indicates that processes unrelated to the reductive half-reaction contribute to the kinetic barrier to catalysis. Interestingly, both SDHR55M and SDHH57A have a nearly pH-invariant kcat similar to the SDHWT Kd(sulfite) profile.

A close correlation between the behavior of the steady-state kinetic parameters and Kd sulfite was also observed for both SDHR55M and SDHH57A (Table 4 and Fig. S2). Due to the very low affinity of SDHR55M for the substrate, sulfite, meaningful data could only be determined at pH 5.5 and 6, with the pH 7 data set clearly demonstrating the extreme increase in Kd sulfite at that pH.

Only limited data could be collected for SDHH57A, since preparations of this protein yield much less enzyme than those of either SDHR55M or SDHWT. However, a plot of reaction rates versus sulfite concentrations at different pH values clearly shows that, similar to what was observed with the apparent Km(sulfite) values for this enzyme, Kd(sulfite) reaches a minimum at pH 7. These observations strongly suggest that the kinetic effects observed in the substituted SDH proteins are a direct result of the pH dependence of elementary steps in the enzyme's mechanism.

Characterization of the Molybdenum Centers of SDHR55M and SDHH57A—The X-band continuous wave EPR spectra for SDHR55M and SDHH57A are shown in Fig. 4. For SDHR55M (trace 2) the principal g values (gX, gY, and gZ = 1.951, 1.960, and 1.989) are similar to those for SDHWT (gX, gY, and gZ = 1.9541, 1.9661, and 1.9914) (12, 13). For SDHH57A at low pH (trace 1), the spectrum shows a well defined low field turning point (gZ = 1.987), but the intermediate and high field regions are each split into two components. One explanation of these features is to attribute them to two structurally different Mo(V) centers with different principal g values. On the other hand, since the amplitudes of these components are similar, the question may arise whether they result from hyperfine splittings at gX and gY. It is easy to distinguish between these two possibilities by recording an EPR spectrum at a different microwave band in order to see if the positions of the EPR features scale in proportion with the microwave frequency. Such measurements were performed at the microwave Ka-band (∼30 GHz; Fig. S3), and it was established that the EPR spectral features belong to two species, I and II, with different sets of principal g values (gX, gY, and gZ = 1.950, 1.962, and 1.987 and gX, gY, and gZ = 1.946, 1.959, and 1.987, respectively, with gZ being the same for both centers.

The g values of Species I are similar to those of high pH SO or SDHWT (33), but the second set is somewhat different, and the question arises whether this change could be caused by some alteration of the exchangeable equatorial ligand in Species II. In order to answer this question, ENDOR measurements at different EPR positions were performed (Fig. S4). The ENDOR spectra obtained (Fig. S4) exhibit broad shoulders with a splitting of up to 8 MHz, centered about the central sharp peaks. These shoulders were shown to arise from the OH ligand proton in the high pH form of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes (34). Thus, the current ENDOR measurements (Fig. S4) have shown that the characteristic features of an equatorial OH-ligand proton are present with unchanged amplitude even at the highest field turning point that is solely contributed by Species II. This observation means that the exchangeable equatorial ligand is the same for both species and that it is unlikely to be responsible for the variability of the principal g values. Rather, the interactions of Species I and II of SDHH57A with the active site surroundings somehow perturb the d-orbitals of Mo(V) slightly differently. The individual structures giving rise to species I and II are likely to be very similar to one another. However, the overlap of their signals makes it impossible to investigate them separately by pulsed EPR.

Structure of SDHR55M—The Arg-55 side chain of SDHWT occupies an important position close to the substrate binding site, where it makes hydrogen bonds to the equatorial oxo ligand of the molybdenum, to Gln-33 OE1, and a nearby water molecule. It also forms a salt bridge, comprising two hydrogen bonds, with propionate-6 of the heme moiety of the cytochrome subunit (Fig. 1D), which effectively locks the propionate group into position (11). The guanidinium group of Arg-55 stacks against the imidazole ring of His-57, potentially forming a long hydrogen bond (3.5 Å) and is also found in proximity (3.8 Å) to Tyr-236.

In the crystal structure of SDHR55M, the side chain of Met-55 does not occupy the same position as Arg-55 in the SDHWT structure; instead, it is bent away, packing into a small cavity between the side chains of Leu-121 and Gln-33. The space occupied by Arg-55 in the wild type enzyme appears to be largely empty in SDHR55M, and a water molecule that is hydrogen-bonded to Arg-55 in SDHWT and is in a position to interact with the substrate/product is missing in SDHR55M (Fig. 5, A and B). A small movement of the Gln-33 side chain causing a 1.0-Å shift in the position of the Gln-33 OE1 may be due either to the loss of interaction with Arg-55, to the position of Met-55, which is located 3.0 Å from Gln-33 OE1 and potentially forms an S–O hydrogen bond, or to the loss of the water molecule associated with Arg-55.

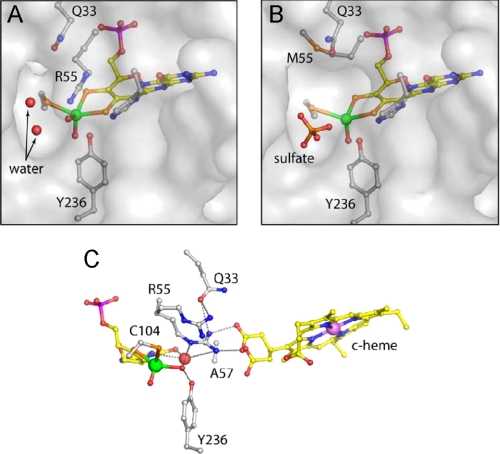

FIGURE 5.

Active site structures of SDHR55M and SDHH57A. A and B show a transparent surface at the substrate binding sites of SDHWT and SDHR55M, respectively. The water-filled cavity adjacent to the equatorial oxygen is larger in the mutated enzyme and is occupied by a sulfate ion. C, hydrogen bonding network around the active site of SDHH57A in a similar view as SDHWT in Fig. 1D. The two alternative positions for Arg-55 and the heme propionate group are shown. An additional water molecule occupies a site close to the pterin, and fulfills potential hydrogen bond contacts.

In SDHR55M, the interactions with the heme propionate-6 moiety are also disrupted, and as a result, the propionate displays greater mobility, confirming our earlier suggestions that Arg-55 contributes to the positioning of the propionate-6 moiety (11). Propionate-6 has been modeled in two conformations, with ∼70% of this group remaining in the same position as in SDHWT and ∼30% rotated around the C3D-CAD bond, displacing a nearby water molecule (Fig. 5).

Structure of SDHH57A—The His-57 side chain of SDHWT is positioned at the side of the substrate binding site between the side chains of Arg-55 and Tyr-236, with His-57 NE2 forming a hydrogen bond to Tyr-236 OH. His-57 also contributes to the molybdopterin binding site via a hydrogen bond from His-57 ND1 to molybdopterin O4 (11, 13) (Fig. 1D).

The structure of SDHH57A confirms the substitution of His-57 with the smaller alanine and identifies an additional water molecule that sits close to the position occupied by the imidazole ring in SDHWT. This water is at a distance to form hydrogen bonds with both N5 and O4 of the molybdopterin. In contrast with the SDHY236F and SDHR55M active site mutants of SDH, the molybdenum site is fully occupied, probably reflecting the more distant position of His-57 from the molybdenum center and the absence of a direct link to a molybdenum ligand. One consequence of the H57A substitution indicated by the difference electron density appears to be increased mobility of both the Arg-55 side chain and the interacting propionate-6 side chain of the heme. These latter side chains have both been modeled in two alternative conformations in this structure; ∼65% is in the same position as in SDHWT, whereas 35% occupies an alternative position in which the salt bridge is disrupted (Fig. 5C and Fig. S5). These two alternative conformations may also account for the two different EPR signals for SDHH57A (Fig. 4; see above).

The data, together with the structure of SDHY236F, reveal that both Tyr-236 and His-57 are necessary to stabilize Arg-55 in a position for optimal hydrogen bonding to the heme 6-propionate.

Presence of Sulfate in the SDH Active Site—Although sulfate is known to inhibit the catalytic activity of SDH and despite the fact that the crystallization medium contained 2.2 m sulfate in all cases, sulfate is not seen in the active sites of SDHWT, SDHY236F, or SDHH57A (11, 13). However, sulfate is present in the active site of SDHR55M, where it appears to displace the equatorial water/hydroxo ligand of the molybdenum as well as three solvent molecules that occupy the substrate-binding site in the wild type structure (Figs. 5 and 6). The sulfate anion interacts with Tyr-236 OH (2.7 Å), Arg-109 (two hydrogen bonds, 2.8 Å to NH1 and 2.9 Å to NH2), the main chain nitrogen of Gly-106 (2.9 Å), Cys-104 Sγ (3.0 Å), and two water molecules (2.5 and 2.7 Å). One of the sulfate oxygen atoms is close to the position occupied by the equatorial water/hydroxo ligand in the SDHWT structure, but the 3-Å distance from the molybdenum is too long for a direct molybdenum sulfate/sulfite bond.

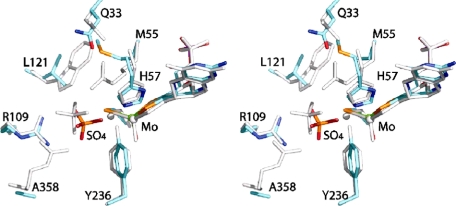

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of the position of bound sulfate in the active sites of SDHR55M and CSO. The stereoview shows the two active sites superimposed with the CSO residues colored gray and the the SDHR55M atoms colored as follows: molybdenum (green), sulfur (orange), phosphorous (magenta), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue), and carbon (cyan). Labels show residues with SDH numbering.

Sulfate is found in the substrate binding site of all reported CSO crystal structures (10, 14). Although the position of sulfate in CSO is similar to that of the sulfate seen in SDHR55M, a significant difference is that the equatorial oxygen on the molybdenum center is still present in the CSO structures, and the sulfate is rotated with respect to the sulfate in SDHR55M so that none of the oxygen atoms is directed toward the molybdenum (Fig. 6). The presence of sulfate in the active site of SDHR55M could be indicative of an increased inhibition of this enzyme by sulfate, and we explored this possibility by carrying out sulfate inhibition experiments with SDHWT and SDHR55M. Since Km(sulfite)(app) for SDHR55M is extremely high (Table 3), investigations were carried out at pH 6 to allow the easy addition of excess sulfate to the assay mixture. Using standard assay conditions, increasing amounts of sodium sulfate (maximum of 80 mm) were added to the reaction mixture. For SDHWT, plots of the reaction velocity versus the amount of sulfate present clearly show an exponential decay, with 50% inhibition occurring at an I0.5 pH 6 of 22.79 mm. In contrast, for SDHR55M, the observed decrease of activity with increasing amounts of sulfate was much more linear and could be fitted equally well with a linear equation or an exponential equation. An I0.5 pH 6 value of 36.65 mm could be deduced from the exponential data fit. From this finding it appears as if SDHR55M is in fact slightly less susceptible to sulfate inhibition than SDHWT. However, this can be shown to be not necessarily true if the concentration of sulfate necessary to achieve 50% inhibition is expressed in terms of “excess over Km(sulfite)(app).” For SDHWT, 22.79 mm sulfate corresponds to ∼5.7 × 104 times Km(sulfite)(app), whereas for SDHR55M, 36.65 mm sulfate corresponds to only about 40 times Km(sulfite)(app) of this enzyme, a difference of 3 orders of magnitude that clearly shows the higher susceptibility of SDHR55M to inhibition by sulfate. Inhibition of both SDHWT and SDHR55M by sulfate at pH 6 was investigated further by deriving the kinetic parameters for each enzyme at 0, 10, 30, and 60 mm sulfate present in the assay (data not shown). Analysis of this data revealed complex nonlinear responses in the inhibition that indicate the potential presence of multiple binding sites for sulfate as well as a pH-dependent change in the strength and type of the prevalent inhibition that is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss in detail.

DISCUSSION

Although enzymatic sulfite oxidation has been studied for more than 4 decades, the molecular details of this process are still not well understood. In all enzymatic catalysis, the formation of the enzyme-substrate complex and the breakdown of this complex into the reaction products are critical parameters, and our data presented above show for the first time how the three conserved active site residues Tyr-236, Arg-55, and His-57 shape the activity of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes by influencing these processes. Our data suggest that crucial factors in these processes are maintaining an optimal alignment of the active site environment and possibly facilitating electron transfer between the molybdenum and heme redox centers (11, 13).

Both Tyr-236 and Arg-55 are within Van der Waals contact distance of the molybdenum center and are hydrogen-bonded to the reactive equatorial oxo/hydroxo/water ligand. His-57 is located slightly further from the molybdenum. In all three cases, amino acid substitution led to marked changes in the alignment of the active site residues, particularly the position of the side chain of Arg-55 and in the catalytic activity of the resulting enzymes. Since no changes in the ligand environment of the heme c group were made and crystallography revealed few conformational changes around the heme iron atom, it is unlikely that the physical properties of this redox center have been altered as a result of the amino acid substitutions.

The kinetic data for SDHY236F suggest that Tyr-236 clearly affects enzymatic turnover, since the substitution decreases the turnover number of the SDH nearly 10-fold at the pH optimum of 8–9. The turnover numbers of SDHR55M are also affected negatively and are only slightly higher than those of SDHY236F, although we note that it was only possible to measure SDHR55M turnover reliably up to pH ∼ 8. We have identified a number of possible explanations for the reduction in catalytic activity that could apply to both substitutions. First, these effects could be mediated by the loss of the hydrogen bond from either Tyr-236 or Arg-55 to the equatorial oxo ligand of the molybdenum center. It is likely that these hydrogen bond interactions help stabilize the molybdenum center in an active state, since we see some loss of molybdenum in the structures of SDHR55M and SDHY236F but not in wild type or His-57-substituted enzymes. Second, both structures identify a disruption of the salt bridge between Arg-55 and heme propionate-6, which may affect electron transfer between the two redox centers, although we note that the Mo–Fe distance of 16.6 Å may be close enough to allow electron “tunneling” to occur (35). Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that the reduced activity is due to changes in the redox properties of the molybdenum atom, although we have so far failed to find evidence for such changes (13).

It is also interesting to note that in SDHWT and SDHY236F, kcat(app) is clearly pH-dependent in a similar manner, whereas in SDHR55M and SDHH57A, kcat(app) values were steady from pH 6 to pH 8, with SDHH57A exhibiting a single pKa in the high pH range above pH 9. As expected by its greater proximity to the molybdenum center, the effect of the R55M substitution on enzymatic turnover is much more severe than that of the H57A substitution; however, in both cases, the pKa value at pH 7.5 seen in the SDHWT kcat(app) values is lost. The data imply that both His-57 and Arg-55 have a role in defining this low pH pKa.

The R55M substitution also led to a significant increase in Km(sulfite)(app) by 2–3 orders of magnitude, which, in addition to the observed reduction in kcat(app) is probably exacerbated by changes in the formation rate of the enzyme-substrate complex and/or the rate at which the complex dissociates without catalysis having been achieved. These latter two effects would be specific to the R55M substitution, since SDHY236F shows a similarly reduced rate of turnover while maintaining a much higher substrate affinity. The less severe increase in Km(sulfite)(app) for SDHY236F and SDHH57A may be at least partially due to disturbances in the position of Arg-55, since the crystal structures of both SDHY236F and SDHH57A show that this residue is sensitive to its interactions with Tyr-236 and His-57. An entirely different and previously unobserved change in the pH dependence of Km(sulfite)(app) occurred in SDHH57A ; in all wild type and substituted SDH/SO enzymes studied so far, the affinity for the substrate increases at lower pH values, but in SDHH57A, a minimum affinity for sulfite was reached at pH 7, indicating that His-57 is important in maintaining substrate affinity below pH 7, where the bulk of the substrate will be present in its protonated HSO–3 form. At pH 7 and below, the His-57 imidazole ring should also be fully protonated, and the effect of His-57 on substrate binding may be exerted through its interactions with Arg-55.

Substitution of Arg-55 with methionine essentially creates an open space at the center of the SDH active site and disrupts the hydrogen bond network around the molybdenum and connecting the molybdopterin and heme redox centers. At the same time Arg-55 is also the innermost of the positively charged residues that line the active site channel of both SDH and CSO/HSO enzymes. There is evidence from the CSO structures that the arginine residues in the active site channel (Arg-138/55, Arg-190/109, and Arg-450, –; CSO/SDH numbering) are involved in achieving the correct orientation of the incoming sulfite molecule with respect to the molybdenum center (10).

The crystal structure of SDHR55M is the only structure of SDH (11, 13) that has a sulfate molecule bound at the active site, despite the fact that the crystallization medium contains 2.2 m ammonium sulfate in all cases (Fig. 6). Modeling a sulfate molecule in the substrate binding site of SDHWT in the same position and orientation as the sulfate in the SDHR55M structure demonstrates that there is no clash with the position of the Arg-55 side chain and that two sulfate oxygen atoms are positioned to form hydrogen bonds with NE and NH2 of Arg-55. However, the position and orientation of the sulfate molecule in the SDHR55M active site is slightly different from that seen in the CSO structures (10), since one of the sulfate oxygen atoms is positioned facing the molybdenum active site. Although the sulfate oxygen is too distant to actually bond to the molybdenum, it does appear to be able to displace the equatorial oxo/hydroxo/water ligand of the molybdenum center in the absence of Arg-55. We therefore propose that Arg-55 plays an important role not only in substrate binding, as demonstrated by our kinetic data, but also in product dissociation from the active site.

It is probable that the composition of the crystallization medium facilitates the formation of the sulfate complex seen in the crystal structure (Fig. 5B), which would be showing in effect a sulfate-inhibited form of the SDH. It seems less likely that the loss of the equatorial oxo/hydroxo/water ligand to the molybdenum center seen in the crystal structure is a permanent feature of SDHR55M. A complete loss of the equatorial molybdenum ligand would be expected to have much more pronounced effects on catalysis, since this ligand is central to the formation of the enzyme-substrate complex. Pulsed EPR studies that are in progress, including 17O labeling experiments, should provide important insight concerning the structure of the Mo(V) center of SDHR55M.

It is not clear why the wild type and other substituted SDH structures do not have sulfate bound in the active site channel. One speculative possibility is the loss of a water molecule in the SDHR55M structure, which hydrogen-bonds to Arg-55 NH2, Glu-33 OE1, and Gly-119 nitrogen in the wild type enzyme. This water is in a position that would allow it to hydrogen-bond to the substrate/product, and we propose a possible role in enzyme activity for this water molecule, which could displace the product sulfate from the molybdenum to become the water/hydroxo ligand of the reduced molybdenum redox center.

The changes seen in catalysis and the structure of SDHR55M are also of interest, because this substitution is related to the R160Q substitution in the human sulfite oxidase (36), which is of clinical relevance and has been identified in an SO deficiency patient (14). In HSO, Arg-160 (Arg-138 in CSO) probably occupies a position equivalent to that of Arg-55 in SDH in the active site. Under standard assay conditions at pH 8, the Km(sulfite)(app) of HSOR160Q was lowered by a factor of 100, and kcat(app) was decreased by ∼6.7 times relative to HSOWT (36). The decreases in both values are nearly identical to those reported in this paper for SDHR55M, suggesting that the kinetic effects of the R160Q and the R55M substitutions are quite similar. The sulfite oxidases from vertebrates are closely related, and the crystal structure of a R138Q-substituted CSO was recently reported (14). The structure showed a slightly altered position of Gln-138 compared with that occupied by Arg-138 in CSOWT and small changes in the relative positions of Tyr-322 and Arg-190 (equivalent to Tyr-236 and Arg-109 in SDH), both located in the active site channel of the vertebrate sulfite oxidases (14). The major change observed in the CSOR138Q active site, however, was a pronounced change in the position of the side chain of the outermost of the three arginines, Arg-450 (replaced by an alanine residue in SDH), which results in a narrowing of the active site entrance channel and was proposed to serve as a gating mechanism (14). Since this gating mechanism clearly cannot be functional in SDH, which lacks an Arg-450 equivalent, and in view of the similarity of the kinetic data for HSOR160Q and SDHR55M, it is unclear what influence the gating mechanism has on sulfite oxidation.

In summary, this work presents for the first time a comprehensive kinetic and structural analysis of the effect that the amino acid environment of the SO/SDH active site has on enzymatic catalysis. Substitution of Tyr-236 slows down enzymatic turnover significantly, whereas only a moderate effect on substrate affinity was observed. Our data indicate that Arg-55 is the most important of the three conserved active site residues, since it mediates substrate binding and product release as well as influencing turnover. SDHR55M was the least catalytically competent (Fig. 3F) of the three substituted enzymes investigated here. We have also uncovered the previously unrecognized role of His-57 in substrate binding and low pH catalysis. Additionally, for SDHH57A, the presence of two active site structural conformations and two distinct EPR forms raises the possibility of more than one catalytic pathway. The similarity of the SDHR55M data to data previously reported for HSOR160Q clearly shows the applicability of SDH-derived data for enzymatic sulfite oxidation in general.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Raitsimring for helpful discussions concerning the EPR spectra.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant [grant-num]GM-37773[/grant-num] (to J. H. E.). This work was also supported by a grant and fellowship from the University of Queensland (to U. K.), an Endeavor International Postgraduate Research Scholarship from the University of Queensland (to T. D. R.), and by the Science and Technology Facilities Council Daresbury Laboratory (for S. B.). This work was also supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Service Award (to K. J.-W.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 2CA3 and 2CA4) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains Figs. S1–S5 and Table S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: CSO, chicken liver sulfite oxidase; HSO, human liver sulfite oxidase; SDH, sulfite dehydrogenase; Bistris, 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol; Bistris propane, 1,3-bis-[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane; ENDOR, electron-nuclear double resonance; WT, wild type.

References

- 1.Kappler, U. (2008) in Microbial Sulfur Metabolism (Friedrich, C. G., and Dahl, C., eds) pp. 151–169, Springer, Berlin

- 2.Suzuki, I. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 243 447–454 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappler, U., and Dahl, C. (2001) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajagopalan, K. V. (1980) in Molybdenum and Molybdenum-containing Enzymes (Coughlan, M. P., ed) pp. 243–272, Pergamon Press, Oxford

- 5.Hansch, R., Lang, C., Riebeseel, E., Lindigkeit, R., Gessler, A., Rennenberg, H., and Mendel, R. R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 6884–6888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karakas, E., and Kisker, C. (2005) J. Chem Soc. Dalton Trans. 21 3459–3463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng, C., Tollin, G., and Enemark, J. H. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774 527–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enemark, J. H., and Cosper, M. M. (2002) Met. Ions Biol. Syst. 39 621–654 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendel, R. R., and Bittner, F. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763 621–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kisker, C., Schindelin, H., Pacheco, A., Wehbi, W. A., Garrett, R. M., Rajagopalan, K. V., Enemark, J. H., and Rees, D. C. (1997) Cell 91 973–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kappler, U., and Bailey, S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 24999–25007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kappler, U., Bennett, B., Rethmeier, J., Schwarz, G., Deutzmann, R., McEwan, A. G., and Dahl, C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 13202–13212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappler, U., Bailey, S., Feng, C. J., Honeychurch, M. J., Hanson, G. R., Bernhardt, P. V., Tollin, G., and Enemark, J. H. (2006) Biochemistry 45 9696–9705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karakas, E., Wilson, H. L., Graf, T. N., Xiang, S., Jaramillo-Buswuets, S., Rajagopalan, K. V., and Kisker, C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 33506–33515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrader, N., Fischer, K., Theis, K., Mendel, R. R., Schwarz, G., and Kisker, C. (2003) Structure 11 1251–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng, C. J., Kedia, R. V., Hazzard, J. T., Hurley, J. K., Tollin, G., and Enemark, J. H. (2002) Biochemistry 41 5816–5821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng, C. J., Kappler, U., Tollin, G., and Enemark, J. H. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 14696–14697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hille, R. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96 2757–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G., Smith, J. A., and Struhl, K. (2005) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, John Wiley & Sons Inc., Hoboken, NJ

- 20.Kappler, U., and McEwan, A. G. (2002) FEBS Lett. 529 208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridge, J. P., Aguey-Zinsou, K. F., Bernhardt, P. V., Brereton, I. M., Hanson, G. R., and McEwan, A. G. (2002) Biochemistry 41 15762–15769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leslie, A. G. W. (1992) Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACMB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography 26 Version 6.2.3, Medical Research Council, Cambridge, UK

- 24.CCP4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 10 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones, T. A., Zou, J. Y., Cowan, S. W., and Kjeldgaard, M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 47 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A., and Dodson, E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 53 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski, R. A., Macarthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., and Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brody, M. S., and Hille, R. (1999) Biochemistry 38 6668–6677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson, H. L., and Rajagopalan, K. V. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 15105–15113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Astashkin, A. V., Enemark, J. H., and Raitsimring, A. M. (2006) Concepts Magn. Reson. Part B 29 125–136 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aylward, G. H., and Findlay, T. J. V. (1971) in SI Chemical Data, 1st Ed., pp. 122–123, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York

- 32.Dawson, R. M. C., Elliott, D. C., Elliott, W. H., and Jones, K. M. (1969) Data for Biochemical Research, 2nd Ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford

- 33.Enemark, J. H., Astashkin, A. V., and Raitsimring, A. M. (2006) J. Chem Soc. Dalton Trans. 29, 3501–3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Astashkin, A. V., Raitsimring, A. M., Feng, C. J., Johnson, J. L., Rajagopalan, K. V., and Enemark, J. H. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 6109–6118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Page, C. C., Moser, C. C., Chen, X., and Dutton, L. (1999) Nature 402 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garrett, R. M., Johnson, J. L., Graf, T. N., Feigenbaum, A., and Rajagopalan, K. V. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 6394–6398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeLano, W. L. (2002) Pymol, DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.