Abstract

The formation of insoluble cross β-sheet amyloid is pathologically associated with disorders such as Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases. One exception is the nonpathological amyloid derived from the protein Pmel17 within melanosomes to generate melanin pigment. Here we show that the formation of insoluble MαC intracellular fragments of Pmel17, which are the direct precursors to Pmel17 amyloid, depends on a novel juxtamembrane cleavage at amino acid position 583 between the furin-like proprotein convertase cleavage site and the transmembrane domain. The resulting Pmel17 C-terminal fragment is then processed by the γ-secretase complex to release a short-lived intracellular domain fragment. Thus, by analogy to the Notch receptor, we designate this cleavage the S2 cleavage site, whereas γ-secretase mediates proteolysis at the intramembrane S3 site. Substitutions or deletions at this S2 cleavage site, the use of the metalloproteinase inhibitor TAPI-2, as well as small interfering RNA-mediated knock-down of the metalloproteinases ADAM10 and 17 reduced the formation of insoluble Pmel17 fragments. These results demonstrate that the release of the Pmel17 ectodomain, which is critical for melanin amyloidogenesis, is initiated by S2 cleavage at a juxtamembrane position.

Folding of proteins is a highly regulated process ensuring their correct three-dimensional structure. Under pathological circumstances, a soluble protein can be folded into highly stable cross β-sheet amyloid structures, which are believed to play pathological roles in disorders such as Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases. An exception to this general concept is the physiological amyloid structure of the melanosomal matrix formed by the protein Pmel17. Melanosomes are lysosome-related organelles that contain pigment granules (melanin) in melanocytes and retinal epithelial cells (reviewed in Ref. 1). Melanogenesis is believed to proceed through several sequential maturation steps, classified by melanosomes from stage I to stage IV. Maturation of stage II melanosomes requires the formation of Pmel17 intralumenal fibers (2, 3).

Pmel17 (also called gp100, ME20, RPE1, or silver) is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein of up to 668 amino acids in humans (reviewed in Ref. 4). The requirement of Pmel17 for the generation of functional melanin has been shown in a number of different organisms, because, for example, certain point mutations in the Pmel17/silver gene result in hypopigmentation phenotypes (5–7). The most characteristic domain within Pmel17 is a specific lumenal proline/serine/threonine rich repeat domain (see Fig. 1A), that is imperfectly repeated 13 times in the Mα fragment. Importantly, deletion of the rich repeat domain results in a complete loss of fibril formation, pointing to the requirement of Pmel17, and especially the rich repeat domain, in melanin formation (8). Pmel17 exists in different isoforms generated by alternative splicing. Pmel17-i2 is the most abundant isoform, whereas the Pmel17-l isoform contains a 7-amino acid insertion close to the transmembrane domain (9, 10).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT on Pmel17 processing. A, schematic diagram of Pmel17 and epitopes of antibodies. Pmel17 contains five potential N-glycosylation sites indicated by branched structures. The long form of Pmel17, Pmel17-l, is characterized by a seven amino acid insertion (VPGILLT) within the lumenal domain close to the transmembrane domain (TM), which is absent in Pmel17-i. NVS marks a potential N-glycosylation site near this insertion. The epitopes of antibodies αPep13h and HMB45 are indicated. Cleavage by a furin-like PC results in the formation of the Mα and the membrane-bound 26-kDa Mβ fragment, which are connected via disulfide bonds. Release and further processing of the Mα fragment into MαN and MαC fragments results in the formation of fibrils and marks the transition of stage I to stage II melanosomes (dashed line). B, human MNT-1 cells were incubated with increasing amounts of DAPT for 18 h, and then the lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with αPep13h antibody. DAPT treatment resulted in the accumulation of a C-terminal fragment of Pmel17 (CTF), whereas Pmel17 P1 and Mβ fragment were unchanged. C, probing the Triton-soluble fraction with HMB45 revealed increased amounts of the highly glycosylated P2 form of Pmel17 after DAPT incubation. D, detection of Pmel17 amyloidogenic fragments (MαC) in the SDS-extracted insoluble pellet using antibody HMB45. E, murine B16-FO cells treated with increasing concentrations of DAPT. Immunoblotting using antibodyαPep13h revealed the formation of CTF of similar size as in MNT-1 cells. F, time course analysis of Pmel17, Mβ, and Pmel17-CTF after DAPT treatment. The cell lysates were immunoblotted using αPep13h. Pmel17-CTF was detectable after 10 min of incubation with 1 μm DAPT. G, the size of the Pmel17-CTF was determined using an unstained low molecular range peptide standard. The marker peptides were detected by Ponceau S staining and Pmel17-CTF were detected by immunoblot using αPep13h.

Pmel17 traffics through the secretory pathway as a 100-kDa protein (called P1). In the late Golgi compartment it undergoes further glycosylation, resulting in a short lived 120-kDa protein (called P2). P2 is rapidly cleaved within the post-Golgi by a furin-like proprotein convertase (PC) to generate two fragments that remain tethered to each other by disulfide bonds: a C-terminal polypeptide containing the transmembrane domain (Mβ) and a large N-terminal ectodomain (Mα) (2) (Fig. 1A). Consequently, inhibition of this furin-like activity not only prevents the generation of Mα and Mβ fragments but also inhibits the formation of melanosomal striation in HeLa cells (3). These findings suggest that Mα must first be dissociated from the Mβ for melanogenesis to proceed. It is unclear how Mα is released from the membrane. Reduction of disulfide bonds would release Mα from Mβ; alternatively, proteolytic digestion of Mβ should also free Mα from the membrane tether. It has been speculated that, given the presence of lysosomal hydrolases in melanosomes and proteolytic maturation of Pmel17, proteolysis is the more likely mechanism (4). Recently, it was shown that recombinant Mα is able to form amyloid structures in vitro in an unprecedented rapidity, and furthermore, Pmel17 amyloid also accelerated melanin formation (11). These findings demonstrate that mammalian amyloid formed by Pmel17 is functional and physiological.

The insoluble pool of Pmel17 in cells consists mostly of truncated Mα C-terminal fragments (MαC) of heterogeneous sizes, indicating that further processing of Mα occurs after its release from the membrane (8, 12). MαC fragments are found in the insoluble fraction of melanocytes as well as in nonmelanotic cells, the latter after overexpression of Pmel17 (8), and are reduced or absent in amelanotic cells (8, 13, 14). Meanwhile, the C-terminal fragment derived from the Mβ fragment and recognized by a C-terminal specific epitope antibody is less stable, indicating rapid turnover (2).

The presenilin (PS) family of proteins consists of two homologous integral transmembrane proteins, PS1 and PS2, which are part of the γ-secretase complex. The latter consists of presenilin 1 or 2, nicastrin, APH-1, and PEN-2 (15) and catalyzes the cleavage of the hydrophobic transmembrane domain of a burgeoning list of proteins, also called regulated intramembrane cleavage. Other substrates for the γ-secretase-mediated intramembrane cleavage include Notch, amyloid precursor protein (APP), cadherin (E-cadherin), nectin-1, the low density lipoprotein-related receptor, CD44, ErbB-4, the voltage-gated sodium channel β2-subunit, and the Notch ligands Delta and Jagged. Importantly, in Alzheimer disease, the presenilin-mediated γ-secretase cleavage of APP releases the amyloid β-protein fragment, a peptide believed to play a key role in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Interestingly, a recent report described the absence of melanin pigment in presenilin-deficient animals, an observation confirmed by the lack of melanin formation in cells treated with γ-secretase inhibitors (16). The mechanism responsible for this finding is unclear, leading us to ask whether Pmel17 processing is a presenilin-dependent process and, if so, whether this cleavage is involved in melanogenesis.

In this study, we show the presence of an endoproteolytic activity that cleaves the extracellular domain of Pmel17-i at a juxtamembrane position between the known PC cleavage site and the transmembrane domain, which we term the S2 cleavage site, by a TAPI-sensitive ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase protein) protease. This intracellular shedding of Pmel17 after S2 cleavage results in the liberation of the Mα N-terminal ectodomain, the precursor to Pmel17 amyloid, which is able to form insoluble Pmel17 aggregates. The C-terminal transmembrane fragment generated by S2 cleavage is further processed by γ-secretase (S3 cleavage) to release the Pmel17 intracellular domain, which is then rapidly degraded.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Drugs and Antibodies—The γ-secretase inhibitors N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT), the protein kinase C activator phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), and the furin inhibitor Dec-RVKR-CMK were purchased from EMB Biosciences (San Diego, CA). TAPI-2 was purchased from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany). The affinity-purified polyclonal antibody αPep13h against the C-terminus of human Pmel17 was kindly provided by Dr. M. Marks. The tubulin antibody E7 was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (Iowa City, IA). Commercial antibodies include HMB45 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), nicastrin N1660 (Sigma), ADAM10 54012 (AnaSpec, San Diego, CA), ADAM17 PC491 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and the c-Myc (A-14) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell Culture—Murine B16-F0 melanoma cells, human HeLa cells, and murine presenilin-deficient fibroblasts were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and 100 unit ml-1 penicillin/streptomycin. MNT-1 human melanoma cells (a kind gift of Dr. M. Marks) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum, 10% AIM-V medium (Invitrogen), and 100 units ml-1 penicillin/streptomycin.

cDNA Constructs—The plasmid pCI-Pmel17-l encoding the long form of human Pmel17 has been described previously (2) and was kindly provided by Dr. Michael Marks. The pCI-Pmel17-l-Myc was generated by introducing the Myc tag epitope at the C terminus of Pmel17 using pCI-Pmel17-l as a template. The intermediate isoform of Pmel17, pCI-Pmel17-i-Myc, lacking the juxtamembrane 7-amino acid insertion, as well as all other Pmel17 mutants were generated using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Transfections—Plasmids were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or FuGENE (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For nicastrin RNA interference experiments, the cells were transfected twice on two consecutive days with 100 pmol of siRNA duplexes (17) using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. For siRNA knock-down of ADAM proteases, the cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of Pmel17-i and 62.5 pmol of control siRNA (Qiagen; 1027292), ADAM10 siRNA pool (GUCUGUUAUUGAUGGAAGAdTdT, CUGUGCAGAUCAUUCAGUAdTdT, and CUUACAAUGUGGAUUCAUUdTdT; Invitrogen; 1220067, 121220, and 1212209), or ADAM17 validated siRNA AAGAAACAGAGTGCTAATTTA (Qiagen; SI02664508) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection.

Immunoblotting—The cell were lysed in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) for 30 min on ice, and the lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 11,000 rpm. To extract the insoluble pool, the remaining pellets were homogenized in 2% SDS, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, by sonication. The proteins were separated by BisTris or Tricine-SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto 0.45 μm polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). For size determination the prestained molecular mass markers were used until otherwise noted; therefore their migration is only approximate. Following blocking in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk and 0.05% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated sequentially with the indicated primary antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) and quantified using a CCD camera-based imaging system (GeneGnome; Syngene, Frederick, MD). All of the experiments were repeated two to three times, and either the results are expressed as averages of all of the experiments ± S.E. or a representative experiment is shown.

Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry—MNT-1 cells were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT for 3 days. Pmel17 was immunoprecipitated from Triton-solubilized cell lysates with αPep13h antibody. The resultant samples were eluted with water:acetonitril:trifluoro acetic acid 50:50:0.5 (v/v/v) and mixed 1:1 (v/v) with a saturated solution of sinapinic acid in the same solvent prior to spotting on a gold chip for mass spectrometry with a Ciphergen SELDI system (Ciphergen Biosystems, Fremont, CA). Calibration was done using an external peptide standard.

Radiosequencing—HEK293T cells were transfected with pCI-Pmel17-i-Myc using FuGENE reagent. Two days later, the cells were starved for 30 min in methionine-free DMEM and afterward incubated in methionine free DMEM containing 1 mCi of [35S]methionine, 5 μm DAPT, 1% dialyzed fetal calf serum, and 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, for 5 h. The cells were lysed in 1.5 ml of lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and complete protease inhibitor mixture), and the supernatant was precipitated using the c-Myc (A-14) antibody. The precipitates were separated on a 4–12% Nupage (Invitrogen) gel, which had been equilibrated for 30 min at 50 V in the presence of 5 mm thioglycolic acid in the cathode buffer and then transferred onto Immobilon-PSQ (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The radiolabeled Pmel17-C-terminal fragment (CTF) band was excised from the membrane after overnight exposure to film and analyzed by automated Edman degradation, and radioactivity from each fraction was measured by scintillation counting.

RESULTS

Inhibition of γ-Secretase Results in Accumulation of C-terminal Fragments of Pmel17—Previous studies have indicated that the release of the Mα fragment from the lumenal domain of Pmel17 is a critical step in the formation of melanosomal striations (3, 8). In this process, the remaining C-terminal fragment of Pmel17 is apparently degraded rapidly (3, 8). In view of the loss of pigmentation in presenilin-deficient mice, we therefore investigated whether presenilin-mediated γ-secretase cleavage could be involved in Pmel17 processing. We incubated human MNT-1 as well as murine B16-F0 cells with increasing concentrations of the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Immunoblotting with a C-terminal antibody against Pmel17 (αPep13h) demonstrated the expected P1 Pmel17 species at 100 kDa and the 26-kDa Mβ fragment (3) (Fig. 1, B and C). Interestingly, we observed a DAPT-dependent accumulation of a novel Pmel17 C-terminal fragment (Pmel17-CTF) in both cell lines (Fig. 1, B and E). Similar accumulation of Pmel17-CTF was seen with a second γ-secretase inhibitor LY450139 (data not shown). However, this Pmel17-CTF cannot be detected at basal conditions, indicating that it is usually rapidly degraded. Time course studies revealed that the levels of Pmel17-CTF started to increase after only 10 min of exposure to DAPT, again pointing to a rapid turnover of this fragment under normal conditions (Fig. 1F). Because we used prestained molecular mass markers in our SDS-PAGE gels, the molecular masses are only approximate. Using unstained molecular mass markers, the detected molecular mass of ∼8–10 kDa suggests that Pmel17-CTF contains at a minimum the complete C terminus (5.2 kDa) and the transmembrane domain (2.2 kDa) of Pmel17 (Fig. 1G). Because this fragment specifically accumulated after γ-secretase inhibition, it is likely, by analogy to APP and Notch processing (18, 19), to represent a potential substrate for intramembrane proteolysis. The Pmel17-CTF is also considerably smaller than Mβ, which implies, again by analogy to Notch receptor and APP processing where there is an antecedent proteolysis by α-secretase or similar “sheddase” activity, that this peptide is generated after a new cleavage of Pmel17 C-terminal to the PC cleavage site. We designate this cleavage as the S2 cleavage site.

Because it has been shown that inhibition of γ-secretase results in a loss of pigmentation (16), we tested whether inhibition of γ-secretase has an impact on Mα generation. Triton-soluble supernatants and the insoluble pellets extracted by SDS were blotted with HMB45, an antibody that specifically recognizes sialylated Pmel17 present in P2 but not P1 species and in the fibrillar matrix of melanosomes (2, 20, 21) formed by Mα and its cleavage product MαC (8). Increasing concentrations of DAPT resulted in a slight increase in the sialylated form of Pmel17, and to a minor extent, species at 40–50 kDa, the latter representing most likely MαC fragments in the Triton-soluble fraction (Fig. 1C). We observed an identical pattern using the γ-secretase inhibitor LY450139 (data not shown). However, the insoluble pellet did not show any significant effects of DAPT treatment when immunoblotted with HMB45, indicating no overt role of γ-secretase activity on Mα generation (Fig. 1D).

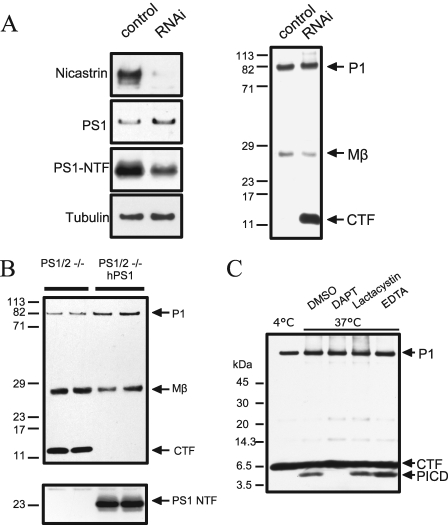

To further test the role of the γ-secretase in the processing of Pmel17, nicastrin expression was inhibited by siRNA treatment in MNT-1 cells (17). As expected, there was a strong decrease in the levels of nicastrin and the PS1 N-terminal fragment, demonstrating that reduction in nicastrin expression led to reduced assembly of PS complex (17) (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the above observations, there was marked accumulation of Pmel17-CTF after siRNA treatment without any changes in the levels of Pmel17 P1 or Mβ species (Fig. 2A). Finally, we transiently expressed Pmel17 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient in both PS1 and PS2 (MEF PS1/2-/-). The absence of both presenilin genes resulted in the accumulation of Pmel17-CTF at steady state basal conditions. But this alteration could be restored in MEF PS1/2-/- transfected with human PS1 (Fig. 2B). Therefore, these results support the concept that Pmel17, or specifically Pmel17-CTF, is a substrate of γ-secretase cleavage.

FIGURE 2.

Pmel17 is substrate for γ-secretase. A, MNT-1 cells were transfected with siRNA duplexes against Nicastrin on two consecutive days. 48 h after the last transfection, cell lysates were analyzed for nicastrin, PS1, tubulin, and Pmel17 by immunoblotting using antibodies N1660, 27G, E7, or αPep13h, respectively. Transfection with nicastrin siRNA duplex resulted in the accumulation of the Pmel17-CTF with no changes to P1 or Mβ fragment (right panel), together with a decrease in the levels of PS1-N TF and nicastrin (left panel). B, PS1-/- PS2-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts with or without stable transfection of human PS1 were transfected with Pmel17-l-Myc construct. Absence of PS1 and PS2 resulted in the accumulation of Pmel17-CTF as detected by immunoblotting with αPep13h. C, crude membrane preparations of DAPT treated MNT-1 cells were incubated for 4 h at 4 °C with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or at 37 °C with dimethyl sulfoxide 1 μm DAPT, 1 mm EDTA or 1 μm lactacystin. Pmel17-ICD production was monitored by immunoblotting with αPep13h antibody. Incubation at 37 °C resulted in the formation of a ∼6-kDa fragment that was absent at 4 °C or after treatment with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Lactacystin and EDTA had no affect on Pmel17-ICD generation.

Pmel17 Is a Substrate for γ-Secretase-mediated Cleavage—Cleavage by γ-secretase results in the release of an intracellular domain (ICD) from type I membrane proteins (22). The half-life of these fragments, such as the APP intracellular domain, can be extremely short, most likely because of its rapid degradation by the proteasome or insulin-degrading enzyme (23, 24). To detect the release of Pmel17-CTF by γ-secretase mediated proteolysis, membrane fractions of MNT-1 cells were pretreated with DAPT to first accumulate Pmel17-CTF and then incubated at 37 °C without DAPT to allow the generation and release of the predicted Pmel17 intracellular domain fragment. Following immunoblotting with αPep13h antibody, a new 6-kDa Pmel17 fragment was detected. This fragment was not seen when the membranes were either incubated at 4 °C or treated with DAPT (Fig. 2C). The addition of lactacystin, a specific inhibitor of the 26 S proteasome, had no effect, whereas EDTA increased the yield of Pmel17-ICD slightly, most likely by inhibiting residual activity of the cytosolic metalloprotease insulin-degrading enzyme (17). These results therefore confirmed that intramembrane cleavage of Pmel17-CTF is mediated by γ-secretase, resulting in the release of Pmel17-ICD.

S2 Cleavage Occurs Independently of PC Activity—It has been shown that activity of a furin-like PC is required for formation of intracellular Pmel17 fibrils (3). To test whether the formation of Pmel17-CTF requires antecedent PC cleavage, we incubated MNT-1 cells with the furin inhibitor Dec-RVKR-CMK for 48 h. After 24 h, DAPT was added to inhibit Pmel17-CTF from further cleavage. As expected, generation of Mβ fragment was blocked after PC inhibition, and there was an accumulation of P2 or the full-length, glycosylated form of Pmel17, which is normally rapidly proteolyzed by PC. At the same time, the DAPT-dependent accumulation of Pmel17-CTF was unaffected (Fig. 3A). The same results were obtained by expressing Pmel17-i and the recently described Pmel17-i PC site cleavage mutant (3) in HeLa cells (Fig. 3B). This suggests that cleavage at the S2 site occurs independently of PC cleavage.

FIGURE 3.

PC and S2 cleavage occur independently. A, MNT-1 cells were incubated with the furin inhibitor Dec-RVKR-CMK or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with or without DAPT. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot using antibody αPep13h. Dec-RVKR-CMK inhibited the formation of Mβ but had no effect on the level of Pmel17-CTF. Longer exposure (lower panel) showed the accumulation of the highly glycosylated P2 form of Pmel17 after Dec-RVKR-CMK treatment. B, HeLa cells were transfected with Pmel17-i or Pmel17-i construct containing a mutation at the PC cleavage site preventing the formation of Mβ (ΔPC). Treatment with DAPT did not abolish Pmel17-CTF formation. C, MNT-1 cells were treated for 4 h with vehicle, DAPT, or Dec-RVKR-CMK with or without 1 μm PMA. The cell lysates were immunoblotted using antibody αPep13h. PMA stimulation decreased the level of Mβ fragment slightly (0.54 ± 0.01, n = 2) but increased the level of Pmel17-CTF (2.19 ± 0.25, n = 2). As seen above, PC inhibition resulted in the accumulation of highly glycosylated Pmel17 P2 species. D, conditioned media from C (first and second lanes) were immunoblotted using HMB45. PMA stimulated the secretion of Pmel17.

S2 Cleavage of Pmel17 Is Induced by Phorbol Ester—Because shedding of the extracellular domain of transmembrane proteins is often stimulated by phorbol esters, we asked whether Pmel17 cleavage fragments are sensitive to phorbol esters and whether this step is related to S2 cleavage of Pmel17. Incubation of MNT-1 cells with PMA resulted in decreased formation of Mβ (0.57 ± 0.02 S.E.; p < 0.05 by Student's t test) (Fig. 3C). However, coincubation of PMA and DAPT showed not only the decrease in Mβ fragment (0.54 ± 0.01), just as seen in the control MNT-1 cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), but also an increase in the level of Pmel17-CTF (2.19 ± 0.25; p < 0.05). In addition, PMA increased the secretion of the soluble Pmel17 (sPmel17) fragment into the medium (Fig. 3D). These results suggested that PMA enhanced S2 cleavage, and consequently, the cleavage products, Pmel17-CTF and sPmel17, are correspondingly elevated.

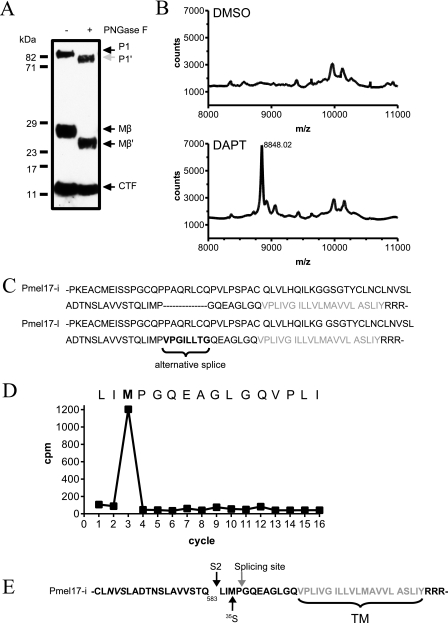

Identification of the Pmel17-CTF Cleavage Site—To determine the position of the S2 cleavage site, we first tested whether the C-terminal fragment is glycosylated because this would make mass determination more difficult. By SDS-PAGE, we estimated the Pmel17-CTF to be ∼8–10 kDa. This size would encompass a potential N-glycosylation site (NVS) at position 568 of Pmel17-i, 25 residues from the transmembrane surface within a region where the S2 cleavage is predicted to take place (Fig. 4E). MNT-1 cell lysates treated with PNGase I digestion and immunoblotted with αPep13h revealed that full-length Pmel17 and Mβ fragment, but not Pmel17-CTF, were reduced in molecular masses after PNGase I digestion. This suggested that either the cleavage site is between the NVS site at position 568 and the plasma membrane or that this NVS motif is not glycosylated (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Position of the S2 cleavage site. A, lysates of MNT-1 cells incubated with DAPT were digested with PNGase F or mock control. Immunoblotting with αPep13h showed a decrease in the molecular masses of P1 (P1*) and Mβ (Mβ*) but not Pmel17-CTF. B, cell lysates of MNT-1 cells treated with DAPT or vehicle (lower panel) were immunoprecipitated with αPep13h antibody and analyzed by MALDI-TOF. A representative MALDI-TOF tracing is shown. C, scheme of the juxtamembrane region of the alternative splicing variants of Pmel17 expressed in MNT-1 cells. The methionines are underlined, and the transmembrane domain is depicted in gray letters. D, Pmel17-i-Myc transfected HEK293 cells were metabolically labeled with 35S in the presence of DAPT. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibody. The precipitates were then separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a membrane, and the Pmel17-CTF band was excised. Radioactivity was measured from the fractions after Edman degradation. The peak in radioactivity was found in fraction 3, suggesting a cleavage between Gln-583 and Leu-584 of Pmel17-I. E, scheme of the S2 cleavage site of Pmel17-i at Gln-583. The glycosylation side NVS is depicted in italic letters. The S2 cleavage (S2), the 35S-labeled Met-586 (35S), and the alternative splicing site are indicated. TM, transmembrane domain.

We next performed mass spectrometry to determine the molecular mass of Pmel17-CTF. MALDI-TOF analysis of αPep13h immunoprecipitates from DAPT-treated MNT-1 cells indicated a mass of 8,840 Da for Pmel17-CTF (Fig. 4B). Alternative splicing results in the long (Pmel17-l) and the more abundant short (Pmel17-i) isoforms that differ by 7 amino acid residues (10) (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the presence of both isoforms may confound the analyses of the cleaved fragments. To obtain definitive evidence of the S2 cleavage site, we metabolically labeled HEK293 cells transfected with Pmel17-i with [35S]methionine in the presence of DAPT. Immunoblotting analysis showed comparable processing of Pmel17 in HEK293T and MNT-1 cells (data not shown). After immunoprecipitation, the radiolabeled Pmel17-CTF was analyzed by radiosequencing, which showed that the peak of 35S radioactivity was recovered in fraction 3 (Fig. 4D). Together with the mass spectrometry results, we conclude that S2 cleavage of Pmel17-i occurs between Gln-583 and Leu-584 (Fig. 4E), 12 residues N-terminal to the predicted membrane surface, in agreement with known shedding sites of other type I transmembrane proteins (19, 25, 26). The resulting Pmel17-CTF has a theoretical molecular mass of 8,590 Da. The difference of ∼250 mass units between the results from the MALDI analysis and the calculated molecular mass is likely due to unknown post-translational modifications of the fragment.

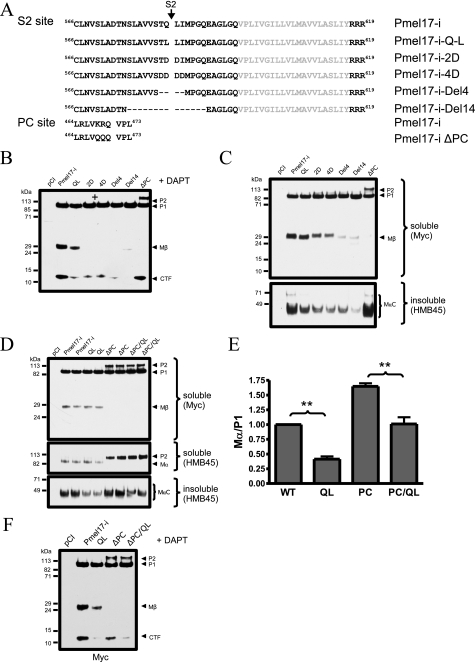

Generation of S2 Cleavage Site Mutants—The preceding findings indicate that the S2 site is important for the amyloidogenic processing of Pmel17, likely by releasing the large intraluminal fragment from the membrane where they are further proteolyzed and then assembled into the amyloid scaffold on which melanin pigment is deposited. To investigate more thoroughly the role of the predicted S2 site on amyloidogenic processing of Pmel17, we generated and tested several Pmel17-i constructs with mutations around this cleavage site. Specifically, these mutations encode either amino acid substitutions (QL, 2D, and 4D) or deletions (Del4 and Del14) in Pmel17-i that might influence S2 cleavage (Fig. 5A). Cell lysates of Pmel1-i mutants expressed in HeLa cells were analyzed by immunoblotting. In the setting of DAPT treatment, we observed a marked reduction in the formation of Pmel17-CTF in all mutants expressed in HeLa cells (Fig. 5B). This suggests that perturbing the S2 cleavage has substantial effects on decreasing the level of γ-secretase substrate. This finding is not surprising, especially in light of the apparent requirement of an antecedent juxtamembrane cleavage before intramembrane cleavage by γ-secretase can occur (27). Moreover, all of the mutants except for the QL construct showed significantly decreased Mβ formation, indicating that these mutations impacted PC cleavage. Importantly, all of the mutants showed a significant reduction in the levels of insoluble MαC fragments (Fig. 5C). Closer inspection of the QL mutant showed that whereas Mβ levels were close to normal, there was a significant 60% reduction in the levels of MαC fragments, suggesting a specific impairment in the formation of amyloidogenic MαC peptides when the predicted S2 site was mutated to impair cleavage (Fig. 5D). However, we did not observe a decrease in either the levels of Pmel17-CTF or MαC fragments in a Pmel17 construct containing the previously described PC site mutation (3) (Fig. 5, B and D). Further, introducing the same Q583L mutation into a construct where the PC site was deleted resulted in a significant 40% reduction in the levels of MαC fragments (Fig. 5, D and E). Treatment of the QL/ΔPC mutant with DAPT resulted in the same decrease in Pmel17-CFT formation as observed in the QL mutation alone (Fig. 5F), again indicating that the effect of the QL mutation on Pmel17-CTF generation is independent of PC cleavage.

FIGURE 5.

Mutation of the S2 cleavage site results in reduced Pmel17 insoluble aggregates. A, generation of Pmel17 mutants. Schematic diagram of Pmel17 S2 and PC site mutations. The transmembrane domain is depicted in gray, amino acids substitutions are underlined, and deletions are shown as dashes. B, Pmel17-i-Myc mutants were expressed in HeLa cells in the presence of DAPT. The cell lysates were immunoblotted using anti-Myc antibody. All of the S2 site mutations resulted in markedly reduced levels of Pmel17-CTF. C, MαC fragments were reduced in all Pmel17 S2 mutants. HeLa cells were sequentially extracted with Triton X-100 and SDS. Equal amounts of protein were separated and immunoblotted with anti-Myc or HMB45 antibodies. All of the S2 site mutations resulted in reduced levels of MαC fragments but unchanged in the PC site mutant (ΔPC). D, Pmel17 QL mutant reduce MαC fragments independent of PC cleavage. The ability to form insoluble MαC fragments was compared between wild type Pmel17, QL mutant (QL), PC site mutant (ΔPC), and a construct containing both mutations (ΔPC/QL). Expression of the PC site mutation had no impact on MαC fragments detected with antibody HMB45, whereas the QL mutant reduced the formation by about 60%, even in the presence of the PC site mutation within the same construct. Immunodetection of P2/Mα in the soluble fraction showed accumulation of P2 in the ΔPC mutants, which were was not observed in type Pmel17 or QL mutant (middle panel). Expression of full-length Pmel17 detected with antibody αPep13h was comparable in all the mutants as compared with control. In addition, Mβ fragment was absent in all ΔPC mutants as expected (upper panel). E, quantification of experiment described in D. The graph shows the MαC to P1 ratio (n = 3 ± S.E., performed in duplicates; **, p < 0.01, Student's t test). F, Pmel17 QL mutant reduced CTF levels independent of PC cleavage. Constructs used in D above were expressed in the presence of DAPT and immunoblotted with anti-Myc antibody. The QL mutants lowered the levels of Pmel17-CTF, independent of PC cleavage.

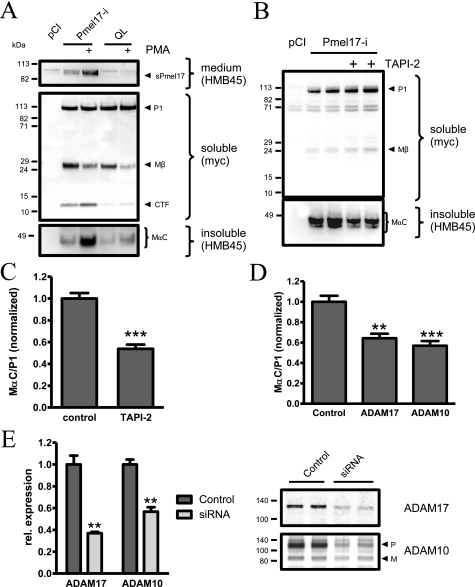

Modulation of S2 Cleavage Changes MαC Levels—Because PMA stimulation increased the formation of Pmel17-CTF, presumably by enhancing S2 cleavage (Fig. 3C), we predicted that this effect should be abolished in S2 cleavage site mutants. Indeed, whereas coincubation of Pmel17-i-transfected HeLa cells with DAPT and PMA increased Pmel17-CTFs as seen before (Fig. 3C), the QL mutant did not respond to PMA stimulation (Fig. 6A). Further, this mutation abolished the PMA stimulated release of sPmel17 into the cell culture medium. Importantly, PMA also enhanced the generation of insoluble MαC fragments in Pmel17-I transfected cells, but this was absent in the QL mutant (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Modulation of Pmel17 S2 cleavage by pharmacological treatment or knock-down of metalloproteases. A, HeLa cells were transfected with Pmel17-i or the QL mutant. Incubation with DAPT or coincubation with PMA for 4 h resulted in increased formation of Pmel17-CTF in case of the wild type construct but had no effect on the S2 cleavage site mutant QL. Blotting of the conditioned media using HMB45 revealed increased secretion of Pmel17 in cells transfected with Pmel17-i but not in the QL mutant. Likewise, PMA induced the formation of insoluble MαC fragments in the insoluble fraction of Pmel17-i transfected cells but failed to do so in the QL mutant. B, HeLa cells transfected with Pmel17-i were exposed to 100 μm of the inhibitor TAPI-2 for 18 h. The soluble and insoluble fractions were immunoblotted using anti-Myc or HMB45 antibodies, respectively. C, quantification of B (n = 2 ± S.E., performed in duplicate; ***, p < 0.001, Student's t test). D, HeLa cells were cotransfected with Pmel17-i and control siRNAs or siRNAs targeting the metalloproteases ADAM10 and ADAM17. Cell lysates were immunoblotted using Myc antibody for Pmel17. Pellet fractions were SDS-extracted and analyzed using antibody HMB45 (n = 3 ± S.E., performed in duplicate; **, p < 0.01; ***, p > 0.001, one-way analysis of variance, Tukey post hoc test). E, the effectiveness of the siRNA knock-down was verified by immunoblotting the lysates for expression of ADAM10 and ADAM17. Knock-down of ADAM10 resulted in a decrease of the proform (P) and the mature form (M). The latter was used for quantification (n = 3 ± S.E., performed in duplicate; **, p < 0.01, Student's t test).

To determine the class of protease that mediates S2 cleavage, we initially tried a number of protease inhibitors, including E64, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride leupeptin, aprotinin, EDTA, and pepstatin A, but were unable to detect any changes in the formation of Pmel17-CTF (data not shown). We then tested the more specific hydroxamic acid-based metalloproteinase inhibitor TAPI-2, known to inhibit a variety of ADAM proteases. Treatment of HeLa cells transfected with Pmel17-i with TAPI-2 for 18 h led to 50% decrease in the level of Triton-insoluble MαC fragments. (Fig. 6C).

We chose to investigate ADAM10 and 17 as candidate proteases for their ability to mediate the formation of MαC fragments, because the vast majority of known ADAM substrates including APP and NOTCH are processed by either one or both of these ADAMs (28). siRNA targeting of ADAM10 and ADAM17 mRNAs led to a significant ∼43 and ∼63% reduction in the protein levels of ADAM10 and ADAM17, respectively (Fig. 6E; n = 3, p < 0.01 Student's t test). Consistent with the TAPI-2 result, siRNA knock-down of ADAM 10 or ADAM 17 both resulted in ∼40% reduction in the levels of MαC fragments normalized to P1 (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these findings indicate that phorbal-sensitive, mediated S2 cleavage by the ADAM family of metalloprotease is the critical step in releasing Pmel17 from the membrane, after which further proteolysis reduces MαC into fragments that assemble into amyloid fibrils.

DISCUSSION

Pmel17 plays a central role in melanogenesis by regulating the biogenesis of the early stages of the melanosome. Release of the Mα ectodomain leads to the formation of melanosomal striations (Pmel17 amyloid) that has a promoting effect on melanin synthesis, presumably by providing a scaffold for pigment deposition (11). Pmel17 fibers show typical properties of amyloid with cross β-sheet structure, staining by amyloid-selective fluorophores, and detergent insolubility. It has been shown that recombinant Mα ectodomain of Pmel17 assembles 4 orders of magnitude faster than other known amyloidogenic substrates like amyloid β-protein or α-synuclein, suggesting that the release of this fragment has to be highly regulated to avoid cellular damage (11). Proteolytic processing of Pmel17 by furin-like proprotein convertase is required to generate Mα and Mβ fragments, both initially tethered to the vesicle membrane. It remains to be elucidated how the Mα fragment is subsequently released from the membrane and from the disulfide linkage to the membrane bound Mβ fragment. Nevertheless, without release from the membrane tether, Mα fragments cannot assemble into fibrils. In this study, we showed that a novel proteolytic activity cleaves Pmel17 in a juxtamembrane position to release Mα from the membrane anchor. This cleavage (between residues 583 and 584), which we designate as the S2 site, is phorbol ester-sensitive and sheds the Mα fragment and a portion of the Mβ fragment into the lumen. Following S2 cleavage, the now N-terminal truncated Mβ fragment (Pmel17-CTF) is quickly recleaved by γ-secretase, and the resultant Pmel17-ICD fragment is then rapidly degraded. Thus, our results show that Pmel17 is a γ-secretase substrate. However, γ-secretase activity itself is not required for the formation of Pmel17 fibril formation because it is the S2 cleavage preceding γ-secretase cleavage that regulates the release of Mα and subsequent formation of Pmel17 amyloid.

Amyloid Formation of Pmel17 and S2 Cleavage—Because the oxidative environment within early melanosomes makes it unlikely that the disulfide bonds are reduced, it has been suggested that that Mα fragments are released from the membrane tether through proteolytic activity (4). Indeed, our results are entirely consistent with the latter speculation. Specifically, we showed that the lumenal domain of Pmel17 is liberated by a novel S2 cleavage close to the plasma membrane. This cleavage results in the release of Mα fragment and through additional proteolysis, the subsequent generation of insoluble MαC fragments. At the same time, an unstable 8.5-kDa C-terminal fragment derived from the residual Mβ fragment is generated (Fig. 7). This C-terminal fragment is unstable because it is quickly recleaved by γ-secretase activity. The resulting Pmel17-ICD peptide, like the other γ-secretase released cytoplasmic domains, is rapidly degraded.

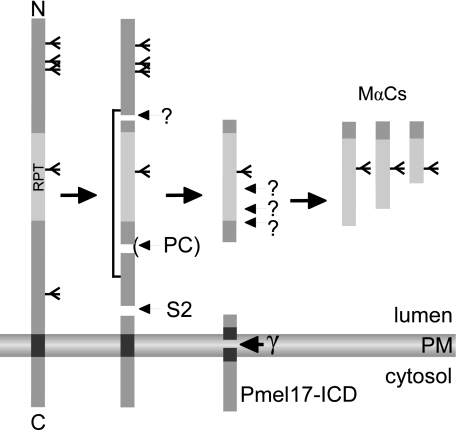

FIGURE 7.

Proposed schematic processing of Pmel17. Pmel17 is first cleaved by PC. The Mα and Mβ fragments remain tethered by disulfide bonds. S2 cleavage then releases the Pmel17 ectodomain consisting of Mα and MαC fragments from the membrane into the lumen of melanosomes. The released ectodomain is then further cleaved into MαN and MαC fragments at presumably multiple cleavage sites (indicated by question marks). These proteolytic events result in smaller MαC fragments that assemble into Pmel17 amyloid. After S2 cleavage, Pmel17-CTF undergoes intramembrane cleavage by γ-secretase, and the released ICD fragment is rapidly degraded.

It has been reported that PC cleavage of Pmel17 initiates the assembly of Mα and is presumably a requirement for the generation of Pmel17 amyloid fibrils (3). Nevertheless, using the same PC site mutant, we and others could not detect reduced amounts of MαC fragments (8). However, neither Hoashi and co-workers nor we examined the cells by electron microscopy as was performed in the original study, so these findings may not be directly comparable. Furthermore, it was reported that expression of α1-antitrypsin Portland (α1-PDX), an inhibitor of PC activity, had a negative impact on Pmel17 fiber formation (3). On the surface, these results are consistent with the results obtained from the PC site mutant as reported in the same study (3). However, multiple groups have recently demonstrated that several members of the ADAM protease family need to be activated by proprotein convertases, such as furin (29–31), and that protein kinase C-dependent activation of α-secretase cleavage of APP also depends on furin activity (32, 33). α-Secretase is a member of the ADAM protease family, and its cleavage of APP is analogous to the S2 cleavage site. Furthermore, the matrix metalloprotease MMP-14, which is PMA-inducible (reviewed in Ref. 34), is cleaved by furin. Interestingly, MMP-14 is present in all stages of melanosomes (35) and has been shown to be a sheddase (36). We therefore speculate that expression of α1-PDX prevents proprotein convertase-mediated activation of the S2 cleavage enzyme and, in so doing, inhibits Pmel17 fiber formation by preventing S2 cleavage.

In this study, all of the mutations at the S2 site showed significant reductions in the levels of MαC fragments and Pmel17-CTF. It is unclear why these S2 mutants, except for the QL mutant, showed such a significant reduction in Mβ generation, especially when, in our hands, deletion of the PC cleavage site had no overt effect on MαC. Although we did not detect gross changes in the processing of Pmel17 biochemically or morphologically in these mutants (data not shown), there may be subtle changes in Pmel17 maturation that affected PC cleavage that we did not appreciate.

Taken together, we hypothesize that amyloid formation of Pmel17 is dependent on S2 cleavage of Pmel17 and that the release of this S2-cleaved ectodomain, which includes a portion of Mβ still linked to Mα by disulfide bond, is the initial precursor of Pmel17 amyloid rather than Mα itself. Because the observed size of MαC fragments is smaller than the released 95-kDa ectodomain (37), further processing by carboxypeptidase is necessary to truncate Mα, a concept that is entirely consistent with our findings (8).

Characterization of S2 Cleavage Activity—Ectodomain shedding has been described for a variety of transmembrane proteins, mostly mediated by members of the ADAM family in particular ADAM 10 and 17 (28). In addition, the shedding of a variety of substrates, like APP, TGF-α, Erb4, or Jagged, is stimulated by phorbol esters, presumably by activating protein kinase C (38–42). It has been shown that a small fraction of Pmel17 molecules is secreted into the extracellular space as sPmel17 (37), although it is unclear whether this secreted peptide has any biological function. Consistent with the shedding of the extracellular domain of a number of type I membrane proteins described above, sPmel17 shedding is also phorbol ester-sensitive. Importantly, the phorbol ester sensitive also extends to the release of MαC fragments (Fig. 6A). It has been demonstrated that cAMP-elevating agents and protein kinase C activation, such as the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate, stimulate melanogenesis and increase the growth of cultured uveal melanocytes (43). If this outcome is due to an increase in the release of Pmel17 from the membrane to generate more MαC fragments, then it is entirely consistent with our results showing the stimulation of S2 cleavage and the coordinated increased in insoluble MαC aggregates by PMA.

In addition, our results indicated that members of the ADAM family of metalloprotease are likely candidates for the Pmel17 S2 site enzyme, because treatment with TAPI-2 inhibitor and siRNA targeting of ADAM10 and ADAM17 all reduced the level of insoluble MαC fragments. However, we cannot exclude that additional members of the large family of ADAM proteases are capable of performing this cleavage.

Role of γ-Secretase—Although we initially speculated that γ-secretase cleavage may be related to the release of the lumenal Pmel17 fragment from the membrane, this is an unlikely scenario in view of the topology of Pmel17. Because it is the release of the N-terminal and not the C-terminal Pmel17 fragment that is critical for melanogenesis, γ-secretase activity cannot mediate Mα amyloid generation because the antecedent S2 cleavage has to take place first and would have released Mα from the membrane. Given this, what is the role of presenilin in Pmel17 metabolism? A signaling function of the intracellular domain has been established for Notch (44), but it is still an open question with most of the other γ-secretase substrates (45). In this context, it has been proposed that γ-secretase can function as the “proteasome of the membrane” by removing transmembrane proteins destined for degradation (46). If so, the rapid turnover of the Pmel17-CTF certainly fits this model of γ-secretase function to facilitate the degradation of these membrane intermediates. Furthermore, the fast removal of both Pmel17-CTF and Pmel17-ICD after S2 cleavage is one reason why these fragments have not been described before and also explains the rapid disappearance of Pmel17 C-terminal immunoreactivity as soon as the melanosomal striation is formed (3).

Comparison with Other Amyloidogenic Substrates—There are striking similarities and differences of this functional amyloidogenesis to pathological amyloid formations. In the familial amyloidosis of Finnish type, mutated gelsolin requires sequential cleavage first by furin and then a second cleavage by a metalloproteases to release the mutant amyloidogenic peptide (47). In wild type gelsolin, furin cleavage does not normally take place (48), but only in the setting of the mutation. In the British form of dementia involving the BRI gene product, amyloidogenic processing also involves furin-mediated cleavage to release the mutant BRI peptide (48). In the case of Pmel17, PC cleavage participates in Pmel17 amyloid formation, but it appears that S2 cleavage is required to initiate the membrane release. Other proteins may also been involved in the amyloidogenic processing of Pmel17 (13), especially because S2 cleavage generates a fragment that requires further proteolytic activities to finally generate MαC. Further work will be needed to fully characterize the protease activities responsible for S2 cleavage and to characterize how this cleavage is regulated physiologically, as well as to determine the other proteases that truncate Pmel17 into smaller MαC amyloid fragments. Studying the complex regulation of functional Pmel17 amyloid formation may generate new insights into pathological amyloids of misfolding diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Michael S. Marks for providing antibodies and cDNA constructs and to Dr. David E. Kang for providing the presenilin-deficient fibroblast cells. We thank Dr. Hui Zheng for helpful discussions and for sharing unpublished results. We also thank Matthew Williamson (University of California, San Diego Protein Sequencing Facility) for assisting in the radiosequencing and Dr. Sarah Sagi and Barbara Cottrell for advice on mass spectrometry. The antibody E7 against tubulin developed by M. Klymkowsky was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD, National Institutes of Health and maintained by The University of Iowa Department of Biological Sciences.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AG12376 (to E. H. K.). This work was also supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Emmy Noether Program Grant WE 2561/1-3 (to S. W.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Pmel17-i, intermediate form of Pmel17, Pmel17-l, long form of Pmel17; Pmel17-CTF, Pmel17 C-terminal fragment; Pmel17-ICD, Pmel17 intracellular domain; Mα, Pmel17-derived ectodomain; MαC, C-terminal fragments of Mα; DAPT, N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester; TAPI-2, N-(R)-(2-(hydroxyaminocarbonyl)methyl)-4-methylpentanoyl-l-t-butyl-glycine-l-alanine-2-aminoethyl amide; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; Dec-RVKR-CMK, decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-chloromethylketone; PC, proprotein convertase; siRNA, small interfering RNA; Mβ, C-terminal polypeptide containing the transmembrane domain; PS, presenilin; APP, amyloid precursor protein; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; BisTris, 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol; Tricine, N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine; CTF, C-terminal fragment; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight.

References

- 1.Slominski, A., Tobin, D. J., Shibahara, S., and Wortsman, J. (2004) Physiol. Rev. 84 1155-1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berson, J. F., Harper, D. C., Tenza, D., Raposo, G., and Marks, M. S. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12 3451-3464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berson, J. F., Theos, A. C., Harper, D. C., Tenza, D., Raposo, G., and Marks, M. S. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161 521-533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theos, A. C., Truschel, S. T., Raposo, G., and Marks, M. S. (2005) Pigment Cell Res. 18 322-336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunberg, E., Andersson, L., Cothran, G., Sandberg, K., Mikko, S., and Lindgren, G. (2006) BMC Genet. 7 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon, B. S., Halaban, R., Ponnazhagan, S., Kim, K., Chintamaneni, C., Bennett, D., and Pickard, R. T. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23 154-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spanakis, E., Lamina, P., and Bennett, D. C. (1992) Development 114 675-680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoashi, T., Muller, J., Vieira, W. D., Rouzaud, F., Kikuchi, K., Tamaki, K., and Hearing, V. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 21198-21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adema, G. J., de Boer, A. J., Vogel, A. M., Loenen, W. A., and Figdor, C. G. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 20126-20133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols, S. E., Harper, D. C., Berson, J. F., and Marks, M. S. (2003) J. Investig. Dermatol. 121 821-830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler, D. M., Koulov, A. V., Alory-Jost, C., Marks, M. S., Balch, W. E., and Kelly, J. W. (2005) PLoS Biol. 4 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiamenti, A. M., Vella, F., Bonetti, F., Pea, M., Ferrari, S., Martignoni, G., Benedetti, A., and Suzuki, H. (1996) Melanoma Res. 6 291-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoashi, T., Watabe, H., Muller, J., Yamaguchi, Y., Vieira, W. D., and Hearing, V. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 14006-14016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasumoto, K., Watabe, H., Valencia, J. C., Kushimoto, T., Kobayashi, T., Appella, E., and Hearing, V. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 28330-28338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Strooper, B. (2003) Neuron 38 9-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, R., Tang, P., Wang, P., Boissy, R. E., and Zheng, H. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 353-358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edbauer, D., Winkler, E., Haass, C., and Steiner, H. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 8666-8671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Strooper, B., Saftig, P., Craessaerts, K., Vanderstichele, H., Guhde, G., Annaert, W., Von Figura, K., and Van Leuven, F. (1998) Nature 391 387-390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mumm, J. S., Schroeter, E. H., Saxena, M. T., Griesemer, A., Tian, X., Pan, D. J., Ray, W. J., and Kopan, R. (2000) Mol. Cell 5 197-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kushimoto, T., Basrur, V., Valencia, J., Matsunaga, J., Vieira, W. D., Ferrans, V. J., Muller, J., Appella, E., and Hearing, V. J. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 10698-10703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raposo, G., Tenza, D., Murphy, D. M., Berson, J. F., and Marks, M. S. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152 809-824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunkan, A. L., and Goate, A. M. (2005) J. Neurochem. 93 769-792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cupers, P., Orlans, I., Craessaerts, K., Annaert, W., and De Strooper, B. (2001) J. Neurochem. 78 1168-1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edbauer, D., Willem, M., Lammich, S., Steiner, H., and Haass, C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 13389-13393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng, Q. C., Tikhomirov, O., Zhou, W., and Carpenter, G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 38421-38427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson, J. P., Esch, F. S., Keim, P. S., Sambamurti, K., Lieberburg, I., and Robakis, N. K. (1991) Neurosci. Lett. 128 126-128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown, M. S., Ye, J., Rawson, R. B., and Goldstein, J. L. (2000) Cell 100 391-398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huovila, A. P., Turner, A. J., Pelto-Huikko, M., Karkkainen, I., and Ortiz, R. M. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30 413-422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang, T., Zhao, Y. G., Pei, D., Sucic, J. F., and Sang, Q. X. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 25583-25591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srour, N., Lebel, A., McMahon, S., Fournier, I., Fugere, M., Day, R., and Dubois, C. M. (2003) FEBS Lett. 554 275-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koo, B. H., Longpre, J. M., Somerville, R. P., Alexander, J. P., Leduc, R., and Apte, S. S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 12485-12494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, H. Q., Pan, J., Ba, M. W., Sun, Z. K., Ma, G. Z., Lu, G. Q., Xiao, Q., and Chen, S. D. (2007) Eur. J. Neurosci. 26 381-391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang, E. M., Kim, S. K., Sohn, J. H., Lee, J. Y., Kim, Y., Kim, Y. S., and Mook-Jung, I. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 349 654-659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osenkowski, P., Toth, M., and Fridman, R. (2004) J. Cell. Physiol. 200 2-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chi, A., Valencia, J. C., Hu, Z. Z., Watabe, H., Yamaguchi, H., Mangini, N. J., Huang, H., Canfield, V. A., Cheng, K. C., Yang, F., Abe, R., Yamagishi, S., Shabanowitz, J., Hearing, V. J., Wu, C., Appella, E., and Hunt, D. F. (2006) J. Proteome Res. 5 3135-3144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hikita, A., Yana, I., Wakeyama, H., Nakamura, M., Kadono, Y., Oshima, Y., Nakamura, K., Seiki, M., and Tanaka, S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 36846-36855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maresh, G. A., Wang, W. C., Beam, K. S., Malacko, A. R., Hellstrom, I., Hellstrom, K. E., and Marquardt, H. (1994) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 311 95-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rio, C., Buxbaum, J. D., Peschon, J. J., and Corfas, G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 10379-10387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinkle, C. L., Sunnarborg, S. W., Loiselle, D., Parker, C. E., Stevenson, M., Russell, W. E., and Lee, D. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 24179-24188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canet-Aviles, R. M., Anderton, M., Hooper, N. M., Turner, A. J., and Vaughan, P. F. (2002) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 102 62-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LaVoie, M. J., and Selkoe, D. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 34427-34437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Black, R. A., Rauch, C. T., Kozlosky, C. J., Peschon, J. J., Slack, J. L., Wolfson, M. F., Castner, B. J., Stocking, K. L., Reddy, P., Srinivasan, S., Nelson, N., Boiani, N., Schooley, K. A., Gerhart, M., Davis, R., Fitzner, J. N., Johnson, R. S., Paxton, R. J., March, C. J., and Cerretti, D. P. (1997) Nature 385 729-733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu, D. N., McCormick, S. A., Orlow, S. J., Rosemblat, S., and Lin, A. Y. (1997) Exp. Eye Res. 64 397-404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schroeter, E. H., Kisslinger, J. A., and Kopan, R. (1998) Nature 393 382-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hebert, S. S., Serneels, L., Tolia, A., Craessaerts, K., Derks, C., Filippov, M. A., Muller, U., and De Strooper, B. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7 739-745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kopan, R., and Ilagan, M. X. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5 499-504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Page, L. J., Suk, J. Y., Huff, M. E., Lim, H. J., Venable, J., Yates, J., Kelly, J. W., and Balch, W. E. (2005) EMBO J. 24 4124-4132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen, C. D., Huff, M. E., Matteson, J., Page, L., Phillips, R., Kelly, J. W., and Balch, W. E. (2001) EMBO J. 20 6277-6287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]