Abstract

Viral metagenomics focused on particle-protected nucleic acids was used on the stools of South Asian children with nonpolio acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). We identified sequences distantly related to Seneca Valley virus and cardioviruses that were then used as genetic footholds to characterize multiple viral species within a previously unreported genus of the Picornaviridae family. The picornaviruses were detected in the stools of >40% of AFP and healthy Pakistani children. A genetically diverse and highly prevalent enteric viral infection, characteristics similar to the Enterovirus genus, was therefore identified substantially expanding the genetic diversity of the RNA viral flora commonly found in children.

Keywords: Cardiovirus, Cosavirus, metagenomics, Picornavirus, polio

Metagenomics analyses have revealed a high degree of microbial genetic diversity in environmental and human samples. Human stool, containing numerous bacteriophages and plant viruses (1, 2), also appears to be a readily accessible source of novel eukaryotic viruses (3). Stools from children with acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) are being systematically analyzed by using cell cultures to identify and control remaining foci of poliovirus in 4 endemic countries (www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/laboratory_polio/en/index.html and www.polioeradication.org/content/general/infectedistricts.pdf). Inoculated cell cultures from nonpolio AFP cases show the presence of other, nonpoliovirus, human enteroviruses (HEVs) (4, 5), some serotypes of which have been associated with neurological symptoms. Because HEVs are detected in less than half of the nonpolio AFP cases a majority of these cases remain without a potential etiological agent. To characterize the viruses circulating in this population we used viral particle nucleic acid purification and limited shotgun sequencing, a method initially reported for animal viruses by Allander et al. (6) and extensively used for environmental viral metagenomics (7–9). We genetically characterized multiple picornavirus species (themselves diversified into serotypes) belonging to a previously unreported genus of the Picornaviridae family. Members of this genus were detected in the stools of nearly half of the AFP and healthy children. This high level of viral genetic diversity and prevalence, reminiscent of that observed for HEV infections, indicate that this genus of picornaviruses has the potential to be involved in a variety of diseases.

Results

Metagenomic Identification and Sequencing of a Highly Divergent Picornavirus.

Stool samples from cases of nonpolio AFP were analyzed by using a simple viral particle nucleic acid purification method involving filtration at 450 nm and DNA and RNA nuclease treatment to reduce contamination from bacteria, eukaryotic cells, and nonviral capsid protected nucleic acids. Extracted viral nucleic acids where then amplified in a sequence-independent manner by using 3′ randomized oligonucleotides for reverse transcription, Klenow fragment DNA polymerase extension, and PCR. Amplified DNA libraries where then subcloned and shotgun-sequenced (see Materials and Methods). A stool sample showed the presence of multiple nucleic acids fragments whose in silico translation products were distantly related to Seneca Valley virus (SVV)- and cardiovirus-encoded proteins. These initial picornavirus-like fragments were joined by using long-range RT-PCR, and the extremities of the viral RNA genome were acquired by 5′ and 3′ RACE before sequencing. The genome of the virus, tentatively named Human Cosavirus A1 for human common stool associated picornavirus species A genotype 1 (HCoSV-A1), was 7,634 nt long encoding a 2,124-aa polyprotein.

Another Picornaviridae Genus.

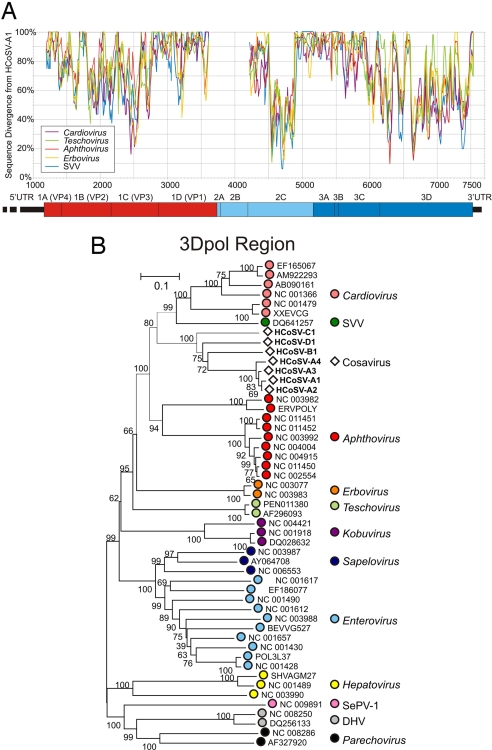

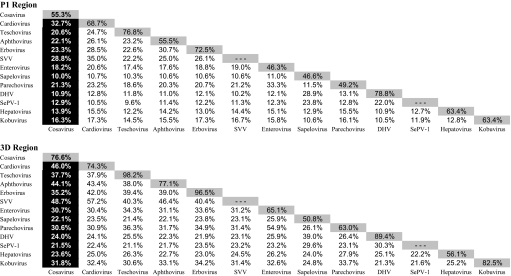

Mean amino sequence divergence between HCoSV-A1 and members of each genus in the Picornaviridae family was calculated by means of a sliding window analysis that revealed short regions of homology between HCoSV-A1 and other genera [Fig. 1A and supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A]. Several highly conserved motifs were identified in the active site of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and in the 2C region. Phylogenetic analysis of alignments of inferred amino acid sequences in the P1, 2C, and 3D regions demonstrated separate grouping of HCoSV-A1 from other genera in all 3 regions (Cosavirus Taxa in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 B and C). Pairwise distances between genera were also calculated in the P1 and 3D regions (Table 1). HCoSV-A1 showed greatest similarity to cardioviruses and SVV in both the P1 and 3D regions (28.8–32.7% for P1 and 46.0–48.7% for 3D; Table 1). In the 3D region, there was also substantially greater similarity to aphthoviruses, teschoviruses, and erboviruses than to other genera (≥35%, compared with <32%). Phylogenetic analyses of the 3D region showed consistent (boot-strap supported) grouping of sequences from the HCoSV-A1, SVV, Aphthovirus, and Cardiovirus grouping and slightly more distant relationships with Teschovirus and Erbovirus genera (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Sequence similarity detection and phylogenetic relationships of cosaviruses with other picornaviridae genera. (A) Mean divergence calculated for a sliding window of pairwise translated protein p distances between HCoSV-A1 and members of the 5 most closely related Picornaviridae genera; a separate plot of the other genera is provided in Fig. S1A. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of 3Dpol region with a representative of each picornavirus genera (2 sequences per species or genus) by neighbor-joining using amino acid p distances. Phylogenetic analysis of the 2C and P1 regions are shown in Fig. S1 B and C.

Table 1.

Amino acid identity between and within Picornaviridae genera

Phylogenetic analysis therefore revealed the presence of a picornavirus sufficiently divergent from existing ones to qualify as the prototype of a new genus in the Picornaviridae family that we named Cosavirus (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Analysis of the Genome and Polyprotein.

The HCoSV-A1 genome showed a relatively low G+C content of 43.8%, most similar to those of teschoviruses (44–45%), duck hepatitis virus (DHV), and seal picornavirus (SePV-1) genera (both 44%). A methionine codon starting at nucleotide position 1165 was found in standard Kozak context (RNNAUGG was AUUAUGG) and used to deduce the start of the polyprotein (10). A short stretch of pyrimidine nucleotides upstream of the polyprotein initiation codon common to all picornaviruses was observed with the sequence UUUUCCUUUUU. Picornavirus structural and nonstructural proteins are typically generated by cleavage with virus-encoded proteinases. The hypothetical cleavage map of the HCoSV-A1 polyprotein was derived from an alignment with other picornaviruses whose experimentally determined or hypothetical protease cleavage sites have been reported (Fig. S2). Comparative analysis suggested the absence of a leader peptide in HCoSV-A1, despite being invariably present in the most closely related genera (Fig. S2). The VP0 of HCoSV-A1 contained a canonical myristoylation motif (GxxxT/S) as GANNS starting at amino acid position 2. The VP1 protein did not contain the integrin-binding RGD motif seen in the VP1 of the aphthovirus foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV) but not in cardioviruses or SVV. The 2A protein was a 30-aa peptide, shorter than cardioviruses (140 aa) but longer than FMDV (16 aa). It was most similar to the C terminus of cardiovirus 2A, a protein that induces a modification of the cellular translation apparatus resulting in 2A release from the ribosome dependent on the canonical DXEXNPG motif present here as DIESNPG. HCoSV-A1 2C was homologous to FMDV 2C, an ATPase affecting the initiation of minus-strand RNA synthesis and whose precursor, 2BC, induces the formation of membrane-associated virus-replicating complexes in the cytoplasm. The HCoSV-A1 2C protein was 321-aa long and included the 3 conserved ATPase motifs (11). The 3B (VPg) peptide included the conserved tyrosine residue located at position 3 (GPYNGPT) homologous to the poliovirus Y3 residue involved in phosphodiester linkage of 3B to the 5′ end of the viral genome. The 3D protein was an RdRp. Of the 8 described conserved motifs in the 3D region of positive-strand RNA viruses (11), 7 were well-conserved in HCoSV-A1.

Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES) in 5′ UTR RNA Region.

The 5′UTR was unusually long at 1,164 nt. Sequences from a total of 8 HCoSV-A1-related viruses were obtained between positions 429 and the start codon to assist in 5′UTR secondary structure prediction methods capable of exploiting phylogenetic and covariance data (see Materials and Methods). Using this dataset, a series of highly conserved stem-loops were found with high probability values concordantly by 2 methods through the sequenced region (Fig. S3A). The region from position 519 to the start codon at 1165 showed both sequence and structural similarities to the IRESs of cardioviruses, aphthoviruses and erboviruses, previously classified as type II IRES (12). Although these genera show the closest amino acid sequence similarity to cosaviruses in protein-coding regions (Fig. 1 and Table 1), the other member of the group, SVV, has a type IV, hepatitis C virus-like IRES considered evidence of cross-viral family recombination (i.e., picornavirus with flavivirus) (13, 14). The secondary structure model of the inferred type II IRES region and 5′ UTR nucleotide motifs conserved across related picornavirus genera (Fig. S3 A and B) and further discussion of the deduced type II IRES structure, 3′ UTR sequence, and genome-scale ordered RNA structures (15) are in SI Text.

High Prevalence of Cosaviruses in Stools of AFP Patients.

PCR primers were generated from conserved nucleotide and amino acids motifs within the 5′UTR and RdRp protein. A total of 28 stool samples from 57 AFP children analyzed were PCR-positive for cosaviruses (Table 2) as were the stools of 6 of 9 healthy children that had been in recent close contact with AFP cases. The clinical symptoms of HCoSV-positive and -negative AFP cases were compared and showed no difference with respect to fever at onset, paralytic asymmetry, progression after 2 weeks, or total number of oral poliovirus vaccine doses previously received.

Table 2.

Frequency of HCoSV and HEV detection by RT-PCR

| Positive/tested | HCoSV | HEV |

|---|---|---|

| AFP | 28/57 (49%) | 31/41 (76%) |

| Controls | 18/41 (44%) | 25/41 (61%) |

High Level of HCoSV Diversity.

Phylogenetic analysis of the 5′ UTR and RdRp PCR products indicated the presence of at least 4 distinct genetic groups (A–D) of human cosaviruses with concordant grouping in both regions (Fig. S4 A and B). Based on these initial analyses 6 HCoSV were selected for further genome sequencing. Nearly full genomes (positions 625-7030) were generated for 2 more group A (HCoSV-A2 and HCoSV-A3), 1 group B (HCoSV-B1) 1 group D (HCoSV-D1), and shorter sequences for 1 group C (HCoSV-C1 position 4761 to 7030) and another group A cosaviruses (HCoSV-A4 position 420-2518 and 4764–7022). Phylogenetic analysis of these viruses in their P1, 2C, and 3D regions confirmed their closer relationship to HCoSV-A1 relative to all other picornaviruses (Fig. 1 B and Fig. S1 B and C).

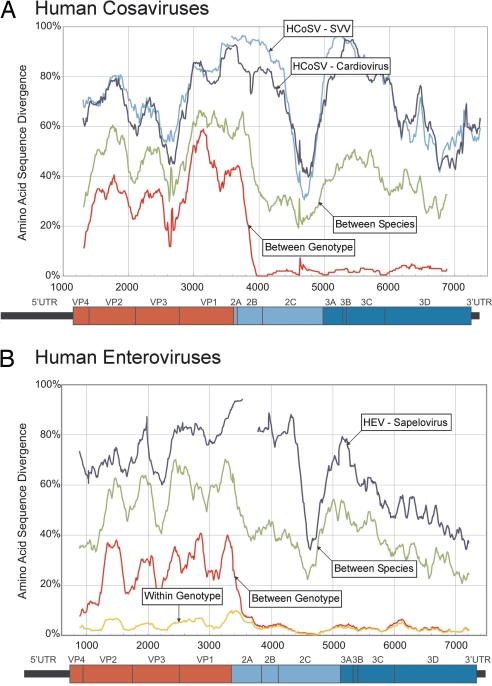

To initiate the classification of cosaviruses, we compared the ranges of sequence divergence between and within cosavirus groups with those found between species and serotypes of HEVs (in the Enterovirus genus) (Fig. 2). These HEVs are classified into 4 species (A–D), each of which containing a large number of serologically distinct serotypes. Sequences from the 4 different cosavirus groups showed only 48–55% amino acid sequence similarity in the P1 region and 63–72% in 3Dpol (Table S1) consistent with their classification as 4 distinct species (16). Cosaviruses within group A showed similarity of 67% in P1, but 97% in 3Dpol (Table S1). Because of strong phylogenetic clustering in the VP1 gene of HEV with the same antibody neutralization profile (i.e., serotype), it has been calculated by Oberste et al. that strains sharing >88% VP1 amino acid identity were highly likely to belong to the same HEV serotype (17). The 3 HCoSV-A viruses shared <60% VP1 identity (data not shown), confirming that the intra-HCoSV-A species diversity was comparable to that seen between serotypes of the same HEV species (Fig. 2). The interspecies and intraspecies genetic distances of cosaviruses and enteroviruses were indeed comparable throughout the length of their genomes (Fig. 2) (consistent with phylogenetic analysis of the P1 of cosaviruses and human enteroviruses (Fig. S4C).

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of cosavirus and HEV diversity. Mean divergences sliding window of pairwise translated protein p distances between cosaviruses (A) and HEVs (B). Cosavirus sequences were compared with those of the 2 most closely related genera, SVV and Cardiovirus (A, blue lines). HEV sequences were compared with those of its most closely related Sapelovirus genus (B, blue line). For cosaviruses divergence were compared between species HCoSVA-D (green) and between genotypes of HCoSV-A species (red). For enteroviruses divergence was compared between species HEVA-D (green) and between genotypes of HEV-B species (red). For HEV intragenotype divergence is shown in yellow.

Based on these genetic comparisons, we propose that the Cosavirus variants characterized to date comprise 4 different species (human cosavirus species A-D or HCoSV-A through HCoSV-D). We further propose that species A contains at least 3 separate genotypes differing in VP1 to a degree consistent with their assignment as separate serotypes (human cosavirus species A serotypes 1–3 or HCoSV-A1 through HCoSV-A3).

Prevalence of HCoSV in Healthy Children.

Stools from 41 healthy children were collected from the same wide geographic area in Pakistan and Afghanistan as the AFP cases (Fig. S5). The female/male ratio of the controls was identical to the AFP cases but the healthy children were slightly younger (AFP mean 54.6 months versus controls 39.8 months; P = 0.04). Stool samples were tested for HCoSV by using the RdRp and 5′UTR PCR. HCoSV RNA was detected in 18/41 (44%) samples (Table 2). The proportion of healthy children infected with HCoSV was not significantly different from that found in AFP cases (28/57 or 49%). Sequences analysis showed the presence of 15 species A and 3 species D viruses (Fig. S4 A and B). The age and sex of HcoSV-positive and -negative children, irrespective of their health status, was not statistically different.

One thousand stool samples collected in Edinburgh for enteric bacteriology screening in May-June 2008, including 147 from children <5 years old, were analyzed for cosaviruses by using the 5′UTR PCR. Only 1 HcoSV-positive sample belonging to species A was positive (64-year-old woman), indicating that infections with HCoSV are geographically widespread, although occurring at a much lower frequency than in Pakistan.

Prevalence of HEV.

The frequencies of HCoSV detection in the AFP and healthy children control groups, although high, were still lower than the remarkably high frequencies of human enterovirus detection (Table 2 and SI Text). A total of 31 from 41 samples from children with AFP and 25 from 41 controls were HEV-positive, with evidence for associations between infections with the 2 virus groups consistent with shared transmission routes, most likely fecal–oral (SI Text).

Discussion

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses has recently classified the Picornaviridae family based on genetic distance into 13 genera (including 28 species), 5 of which include representatives infecting humans (Enterovirus, Hepatovirus, Parechovirus, Kobuvirus and Cardiovirus) (www.picornaviridae.com). Enteroviruses are the most genetically and phenotypically diverse genus, containing 11 species, 7 of which infect human [four HEV species plus 3 recently subsumed human rhinoviruses species (18, 19)] with epidemiology and replication strategies as varied as those of polioviruses and rhinoviruses.

We add here a new genus to the Picornaviridae family, tentatively named Cosavirus consisting of at least 4 species (A–D). Because the first 3 randomly selected members of species A were genetically divergent enough to be considered 3 different genotypes further VP1 sequencing and geographic sampling will likely reveal the presence of numerous other genotypes. The wide range of viral genetic diversity indicates that the distinct Cosavirus species and genotypes, like those of HEV, have the potential to be associated with a range of different phenotypes. HEV infections are extremely common with 5 million to 10 million estimated yearly symptomatic cases in the United States and possibly more than 1 billion cases per year globally (20–22). Like HCoSV in Pakistan, HEVs are commonly found in the stool of healthy infants, including those living in countries with good sanitary conditions (23), and >99% of HEV infections are estimated to be asymptomatic. Previous exposures, age, immune status, sex, and socioeconomic status have a large influence on rates of HEV infection and clinical outcome (22). HEV infections are also characterized by periodic outbreaks of pathogenic serotypes capable of inducing neurological damages, as seen for polioviruses and more recently for enterovirus 71 in Southeast Asia (24). Among the >80 serotypes within the 4 HEV species some have been associated with diverse conditions including pneumonia, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, aseptic meningitis, hepatitis, myocarditis, and type 1 diabetes (22).

The remarkable difference in HCoSV detection rates between the United Kingdom and Pakistan likely reflects improved hygiene over the past century. Of concern is the likelihood of HCoSV infections occurring later in life in low-incidence countries, a factor thought largely responsible for the large-scale outbreaks of poliomyelitis in the United States and other Western countries in the 1950s and 1960s (22). Investigating the potential etiologic role of HCoSV infections in neurological or other picornavirus-like disease presentations, particularly those showing increasing incidences, is a key priority for future diagnostic testing and surveillance for this virus.

The very high prevalence of cosaviruses in South Asia and rarer detection in the United Kingdom, their extensive genetic diversification, and the high mutation and recombination rate of picornaviruses therefore provide the conditions for the members of this Picornaviridae genus to have evolved and continue to evolve a wide range of phenotypes. Considering the ratio of HCoSV to HEV of >50% measured in Pakistan, and assuming equal duration of virus excretion, cosaviruses may be among the most common RNA viruses infecting children in developing countries and part of a still only partially defined enteric viral flora. Despite their high prevalence cosaviruses may have remained undetected because of lack of cytopathic effects in cell cultures or because their high degree of genetic divergence relative to other picornaviruses precluded their detection by serological or nucleic acid hybridization based methods. The high level of genetic diversity of cosaviruses makes it unlikely that all of these variants have only recently emerged in humans.

Viral metagenomics is a simple method for identifying highly divergent new viruses, at least those whose translated protein sequences are recognizably related to existing viral families (6, 25–33). The continued deployment of viral metagenomics-based approach will provide a fuller understanding of the genetic diversity of the viral flora and its impact on human and animal health.

Materials and Methods

Viral Particle Purification and Sequence-Independent Nucleic Acid Amplification.

Processing of stool samples with chloroform and centrifugation was performed according to instructions in WHO's polio laboratory manual. A total of 140 μL of centrifuged stool supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm filter to remove eukaryotic and bacterial-sized particles. The filtrate was then treated with nucleases to digest nonparticle protected nucleic acid. The viral nucleic acids protected from digestion within viral capsids were then extracted and randomly amplified by using a PCR primer with randomized 3′ end as published (25). The amplification products were subcloned, sequenced, and analyzed for sequence similarities to known viruses by tBLASTx (25).

RT-PCR for Cosaviruses and HEV.

Total nucleic acid was extracted from stool supernatants (140 μL per sample) by using a viral RNA/DNA extraction kit (Qiagen). Final elution was in 60 μL of EV buffer. SuperScript II or III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was used to generate cDNA, using 100 pmol of random octamer primer, 10 pmol (each) of dNTP, 10 μL of nucleic acid extract, 1× buffer, 5 mM DTT, 40 units of RNase inhibitor (Roche), and 200 units of RT enzyme in a 20-μL reaction volume. Incubation times and temperatures followed the manufacturer's protocol for random-primed synthesis. All PCRs were nested, with 2 μL of cDNA used as template in the first round of PCR and 1 μL of product from the first round used as template in the second round. All PCRs were performed with 3 units of Taq polymerase (NEB) in 50-μL volume with 0.25 mM dNTP (each) in 1× thermolpol buffer. Amplification products were all run on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Second-round PCR products were treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB) before direct sequencing. All products were sequenced from both directions, with the 2 primers used in the second round of PCR. Sequences were edited and aligned by using Sequencer 4.8 software (Genecodes).

The Cosavirus 5′ UTR PCR used DKV-N5U-F1 (CGTGCTTTACACGGTTTTTGA) and DKV-N5U-R2 (GGTACCTTCAGGACATCTTTGG) for the first round of PCR and primers DKV-N5U-F2 (ACGGTTTTTGAACCCCACAC) and DKV-N5U-R3 (GTCCTTTCGGACAGGGCTTT) for the second round. The first-round PCR also included 4 mM MgSO4 and 0.6 μM of each primer. The second-round reaction mix was identical. For the first round, the PCR cycle included a 3-min denaturation at 95 °C; 10 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 55–50 °C (decrease of 0.5 °C per cycle) for 1 min, 72 °C for 45 s; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 53 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 45 s; a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. For the second round, the PCR cycle included a 2.5-min denaturation at 95 °C; 10 cycles of 95 °C for 45s, 57–52 °C (decrease of 0.5 °C per cycle) for 1 min, 72 °C for 30 s; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s; a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The expected product size was ≈316 bp. The United Kingdom stool samples were tested in pools of 10 by using the same 5′ UTR RT-PCR.

The Cosavirus RdRp region was amplified by using primers DKV IF1 (CTACCARACITTYCTIAARGA) and DKV IR1 (GCAACAACIATRTCRTCICCRTA) for the first round of PCR and DKV IF2 (CTACCAGACATTTCTCAARGAYGA) and DKV IR2 (CCGTGCCAGAIGGIARICCICC) for the second round. The first-round reaction mix also included 3.2 mM MgSO4 and 1.0 μM of each primer. For the first round, the PCR cycle included a 3-min denaturation at 95 °C; 4 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 53 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min; 4 cycles of 95 °C for 45 s, 48 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 40 s; a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. For the second round, the PCR cycle included a 2.5-min denaturation at 95 °C; 4 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 45 s; 4 cycles of 95 °C for 45 s, 50 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 45 s; 25 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s; a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The expected product size was ≈428 bp.

The HEV 5′UTR region was amplified by using primers F15284 (ACADGGTGYGAAGAGYCTATTGAGCT) and F15287 (ATTGTCACCATAAGCAGCCA) for the first round and primers F15285 (TCCGGCCCCTGAATGCGGCTAA) and F15286 (CACCCAAAGTAGTCGGTTCCGC) for the second round (34). The first-round reaction mix also included 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 μM each primer. The second-round reaction mix was identical. For the first and second rounds, the PCR cycle was identical: 3-min denaturation at 95 °C; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 48 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 35 s; a final extension at 72 °C for 6 min. The expected product size was ≈110 bp.

Phylogenetic Analyses.

Sliding window analysis and phylogenetic analyses in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 B and C were performed as published (25). In the sliding window analyses, mean divergences were calculated between translated sequential fragments of 48 nt (16 in-frame codons), incrementing by 12 nt. Phylogenetic analyses of ClustalW aligned regions were carried out by neighbor joining of nucleotide p-distances implemented in the program MEGA4. Bootstrap resampling (values ≥70% shown on branches) was carried out to demonstrate robustness of groupings. For sliding window analysis (Fig. 2) a window size of 100 codons, incrementing by 4 codons per data point, was used.

Picornavirus Sequences for Phylogenetic Analysis.

For determination of sequence divergences between cosaviruses and those of other picornaviruses, sequences were aligned from 2 or more representative serotypes from each species within each of the 9 currently classified genera of picornaviruses, members of the proposed “Sapelovirus” genus and the currently unclassified viruses DHV (35), SVV, and SePV-1 (25). Picornaviruses sequences used are listed in SI Text. The enterovirus sequences used for comparison with cosavirus diversity are also listed in SI Text.

RNA Structure Determination.

Sequences from a total of 8 HCoSV variants were obtained between positions 429 and the start codon, within which considerable sequence variability was observed. Of these, 5 (HCoSV-A1, HCoSV-A2, HCoSV-A4, and HCoSV-A strains 5046 and 5008) belonging to Cosavirus species A grouped with a mean pairwise distance of 95.5%) whereas the remaining 3 (HCoSV-B1, HCoSV-C1, and HCoSV-D1) were more diverse, with mean pairwise distances 79–83%. Alignments of 5′ UTR sequences were analyzed for phylogenetically conserved RNA secondary structures by using RNAz (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAz.cgi) (36) and PFold through the web interface www.daimi.au.dk/∼compbio/rnafold (37). Prediction of RNA secondary structure of single sequences was carried out by using a standard minimum free energy method (MFOLD) (38). Mean folding energies of fragments of the HCoSV-A1 genome and control sequences were determined by the program ZIPFOLD with default settings as described (38).

The genome sequences used for genome-scale ordered RNA structure analysis are listed in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. M. P. Busch and the Blood Systems Research Institute for sustained support and Dr. H. Biswas for statistical analyses. This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01HL083254 (to E.D.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: A provisional U.S. patent application has been submitted.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. FJ438825–FJ438908 and FJ442991–FJ442995).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0807979105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Breitbart M, et al. Metagenomic analyses of an uncultured viral community from human feces. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6220–6223. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.20.6220-6223.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang T, et al. RNA viral community in human feces: Prevalence of plant pathogenic viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005;4:e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkbeiner SR, et al. Metagenomic analysis of human diarrhea: Viral detection and discovery. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e1000011. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon T, Willison H. Infectious causes of acute flaccid paralysis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:375–381. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeed M, et al. Epidemiology and clinical findings associated with enteroviral acute flaccid paralysis in Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allander T, Emerson SU, Engle RE, Purcell RH, Bukh J. A virus discovery method incorporating DNase treatment and its application to the identification of two bovine parvovirus species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11609–11614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211424698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitbart M, et al. Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14250–14255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202488399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards RA, Rohwer F. Viral metagenomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:504–510. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culley AI, Lang AS, Suttle CA. High diversity of unknown picorna-like viruses in the sea. Nature. 2003;424:1054–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature01886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koonin EV, Dolja VV. Evolution and taxonomy of positive-strand RNA viruses: Implications of comparative analysis of amino acid sequences. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;28:375–430. doi: 10.3109/10409239309078440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Salas E, Pacheco A, Serrano P, Fernandez N. New insights into internal ribosome entry site elements relevant for viral gene expression. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:611–626. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hales LM, et al. Complete genome sequence analysis of Seneca Valley virus-001, a novel oncolytic picornavirus. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1265–1275. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellen CU, de Breyne S. A distinct group of hepacivirus/pestivirus-like internal ribosomal entry sites in members of diverse picornavirus genera: Evidence for modular exchange of functional noncoding RNA elements by recombination. J Virol. 2007;81:5850–5863. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02403-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmonds P, Tuplin A, Evans DJ. Detection of genome-scale ordered RNA structure (GORS) in genomes of positive-stranded RNA viruses: Implications for virus evolution and host persistence. RNA. 2004;10:1337–1351. doi: 10.1261/rna.7640104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA. Virus Taxonomy: Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. New York: Academic; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberste MS, Maher K, Kilpatrick DR, Pallansch MA. Molecular evolution of the human enteroviruses: Correlation of serotype with VP1 sequence and application to picornavirus classification. J Virol. 1999;73:1941–1948. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1941-1948.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kistler A, et al. Pan-viral screening of respiratory tract infections in adults with and without asthma reveals unexpected human coronavirus and human rhinovirus diversity. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:817–825. doi: 10.1086/520816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamson D, et al. MassTag polymerase chain reaction detection of respiratory pathogens, including a new rhinovirus genotype, that caused influenza-like illness in New York State during 2004–2005. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1398–1402. doi: 10.1086/508551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strikas RA, Anderson LJ, Parker RA. Temporal and geographic patterns of isolates of nonpolio enterovirus in the United States, 1970–1983. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:346–351. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morens DM, Pallansch MA. Human enterovirus infections. In: Rotbart HA, editor. Epidemiology. Washington, DC: Am Soc Microbiol; 1995. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pallansch MA, Roos RP. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. 4th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 723–775. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witso E, et al. High prevalence of human enterovirus a infections in natural circulation of human enteroviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4095–4100. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00653-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Modlin JF. Enterovirus deja vu. New Engl J Med. 2007;356:1204–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapoor A, et al. A highly divergent picornavirus in a marine mammal. J Virol. 2008;82:311–320. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01240-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox-Foster DL, et al. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science. 2007;318:283–287. doi: 10.1126/science.1146498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palacios G, et al. A new arenavirus in a cluster of fatal transplant-associated diseases. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:991–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones MS, Lukashov VV, Ganac RD, Schnurr DP. Discovery of a novel human picornavirus in a stool sample from a pediatric patient presenting with fever of unknown origin. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2144–2150. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00174-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allander T, et al. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones MS, et al. New DNA viruses identified in patients with acute viral infection syndrome. J Virol. 2005;79:8230–8236. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8230-8236.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Der Hoek L, et al. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Hoogen BG, et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:719–724. doi: 10.1038/89098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welch JB, et al. Detection of enterovirus viraemia in blood donors. Vox Sanguinis. 2001;80:211–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2001.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tseng CH, Knowles NJ, Tsai HJ. Molecular analysis of duck hepatitis virus type 1 indicates that it should be assigned to a new genus. Virus Res. 2007;123:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Washietl S, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF. Fast and reliable prediction of noncoding RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2454–2459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409169102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knudsen B, Hein J. Pfold: RNA secondary structure prediction using stochastic context-free grammers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3423–3428. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuker M. Mfold Web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.