Abstract

Gene expression is potently regulated through the action of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and microRNAs (miRNAs). Here, we present evidence of a miRNA regulating an RBP. The RBP HuR can stabilize and modulate the translation of numerous target mRNAs involved in cell proliferation, but little is known about the mechanisms that regulate HuR abundance. We identified two putative sites of miR-519 interaction on the HuR mRNA, one in its coding region (CR), one in its 3′-untranslated region (UTR). In several human carcinoma cell lines tested, HeLa (cervical), HCT116 and RKO (colon), and A2780 (ovarian), overexpression of a miR-519 precursor [(Pre)miR-519] reduced HuR abundance, while inhibiting miR-519 by using an antisense RNA [(AS)miR-519] elevated HuR levels. The influence of miR-519 was recapitulated using heterologous reporter constructs that revealed a greater repressive effect on the HuR CR than the HuR 3′-UTR target sequences. miR-519 did not alter HuR mRNA abundance, but reduced HuR biosynthesis, as determined by measuring nascent HuR translation and HuR mRNA association with polysomes. Modulation of miR-519 leading to altered HuR levels in turn affected the levels of proteins encoded by HuR target mRNAs. In keeping with HuR's proliferative influence, (AS)miR-519 significantly increased cell number and [3H]-thymidine incorporation, while (Pre)miR-519 reduced these parameters. Importantly, the growth-promoting effects of (AS)miR-519 required the presence of HuR, because downregulation of HuR by RNAi dramatically suppressed its proliferative action. In sum, miR-519 represses HuR translation, in turn reducing HuR-regulated gene expression and cell division.

Keywords: elav, microRNA, post-transcriptional gene regulation, ribonucleoprotein complex, translational control

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are critical regulators of gene expression in mammalian cells (1). They influence key aspects of gene expression including pre-mRNA splicing, 5′ capping, 3′ polyadenylation, nuclear transit, export to the cytoplasm, cytoplasmic transport, storage, translation, and turnover (2). Although many RBPs have housekeeping functions and associate with cellular transcripts, several RBPs have emerged that bind to specific subsets of mRNAs and play essential roles in controlling gene expression patterns in response to cell stimulation. These include a family of RBPs that modulate protein expression patterns in response to external factors by altering the cytoplasmic fate of target mRNAs, primarily by acting as translation and turnover regulatory (TTR)-RBPs (3, 4). HuR is among the most prominent sequence-specific TTR-RBPs influencing the cellular response to stress agents, proliferative signals, immune triggers, and developmental cues (5–8).

HuR contains three RNA-recognition motifs (RRMs) through which it binds to specific mRNAs that often contain AU- or U-rich sequences in their 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) (9, 10). HuR stabilizes many target mRNAs (11), likely by antagonizing the effect of decay-promoting TTR-RBPs. Additionally, in some cases HuR promotes target mRNA translation (12–14), although other times it represses it, particularly when transcripts possess an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (15). Among the HuR target mRNAs are many that encode proliferation-related proteins, including several that influence cell cycle progression (e.g., cyclins A2, B1, D1, p21, p27), growth factor function (e.g., IGF-1R VEGF, EGF, TGF-β, GM-CSF), and transcription factor activity (e.g., c-fos, c-myc, c-jun, p53, myogenin, MyoD, ATF-2) (13, 16, reviewed in ref. 4).

Given HuR's influence on the expression of key proliferative proteins, there is much interest in elucidating how HuR function is regulated. To date, several mechanisms have been identified. First, HuR function is influenced by processes that affect its subcellular localization. HuR is predominantly nuclear, but shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (17); its accumulation in the cytoplasm is linked to its ability to stabilize and modulate the translation of target mRNAs (7). Several kinases have been implicated in the regulation of HuR abundance in the cytoplasm, including at least two (PKC, Cdk1) that directly phosphorylate HuR (18–20). Second, HuR function is influenced by processes that affect HuR association with target mRNAs. HuR phosphorylation at RRM1 and RRM2 by Chk2 affect its interaction with several target mRNAs (21). Third, HuR function is influenced by processes that affect HuR integrity. Very recently, HuR was shown to be subject to proteolytic degradation at aspartate 226 via caspases; cleavage released a peptide that promoted apoptosis (22).

Here, we describe a novel mechanism that regulates HuR levels through the action of a microRNA (miRNA). miRNAs are small (≈22-nt), single-stranded, non-coding RNAs that have emerged as pivotal regulators of gene expression (23, 24). Synthesized as longer transcripts by RNA polymerase II, primary (Pri)miRNAs are processed by the nuclear RNase Drosha into 70-nt, hairpin precursor miRNAs (Pre)miRNAs. After Exportin-5-mediated transport to the cytoplasm, (Pre)miRNAs are further processed by RNase Dicer, giving rise to mature miRNAs that assemble with members of the argonaute (Ago) protein family into RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The miRNA then directs the complex to target mRNAs, typically reducing their translation and/or stability (25–27). Our results indicate that miR-519 targets the HuR mRNA and represses its translation, highlighting the existence of regulation of one type of posttranscriptional regulatory factors (RBPs) by another type of posttranscriptional regulators (miRNAs). Interestingly, while most miRNAs interact with the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs, miR-519 appears to function primarily through its association with the coding region (CR) of the HuR mRNA. The miR-519-mediated reduction in HuR abundance in turn decreased the expression of several HuR target mRNAs and markedly reduced cell proliferation.

Results

miR-519 Modulates HuR Levels.

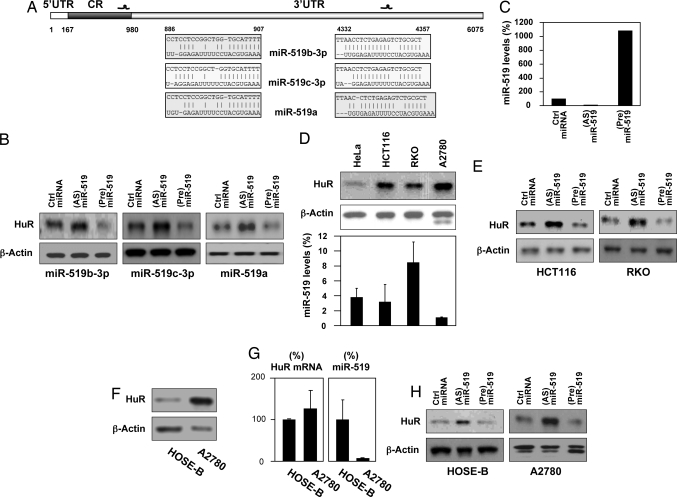

Using the program RNA22, the miR-519 family (supporting information (SI) Fig. S1) was predicted to associate with the HuR mRNA at the coding region (CR) and 3′-UTR (Fig. 1A). Within this cluster (located in chromosome 9, Fig. S1), the effect of miR-519b-3p, miR-519c-3p, and miR-519a on HuR expression was tested in HeLa cells. Forty-eight h after transfection of antisense (AS) transcripts to reduce the levels of each miR-519 or after transfecting precursor (Pre) transcripts to elevate the levels of each miR-519, the levels of HuR were analyzed by Western blotting. (AS)miR-519-transfected cells expressed increased (≈3-fold) HuR levels, while (Pre)miR-519-expressing cells showed lower (2- to 3-fold) levels compared with control miRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 1B). In each case, the increase and decrease in miR-519 levels were comparable to what was seen for miR-519b-3p (≈10-fold lower and higher, respectively, Fig. 1C and data not shown). The effects of miR-519 upon HuR were specific, as reduction or overexpression of other miRNAs predicted to target HuR mRNA (e.g., miR-24, miR-320, and miR-485–3p) did not influence HuR levels (Fig. S2 and data not shown). As anticipated, transfected miRNAs showed a punctate cytoplasmic distribution (Fig. S3).

Fig. 1.

miR-519 influences HuR levels. (A) Schematic of HuR mRNA depicting two predicted target sites for the miR-519 family within the CR and 3′-UTR. Alignment of the HuR mRNA sequences with three members of the miR-519 family; top strand, HuR mRNA; bottom strand, miR-519. (B) The effect of three miR-519 family members on HuR levels was tested by transfecting HeLa cells with the corresponding precursor (Pre) and antisense (AS) transcripts, and with control miRNAs. By 48 h after transfection, the levels of HuR and loading control β-actin were tested in HeLa whole-cell lysates by Western blotting. (C) miR-519 (miR-519b-3p) abundance as measured by RT-qPCR 48 h after transfection of HeLa cells with Ctrl miRNA, (Pre)miR-519, or (AS)miR-519; 18S rRNA levels were used to monitor loading differences. Graph shows representative results from two experiments. (D) In the cell lines shown, HuR and β-actin levels were analyzed by Western blotting (Top) and miR-519 levels (Bottom) were measured as described in C. Graph shows the means and standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. (E) The modulation of miR-519 in the colon carcinoma lines RKO and HCT116, and the analysis of HuR and β-actin were performed as described in B. (F) The levels of HuR and loading control β-actin were examined by Western blotting in the ovarian epithelial line HOSE-B and the ovarian carcinoma line A2780. (G) The levels of HuR mRNA and miR-519 (each normalized to 18S rRNA levels), were analyzed by RT-qPCR. (H) The effect of modulating miR-519 levels in HOSE-B and A2780 cells was studied as described in E.

The levels of HuR and miR-519 were monitored in several cultured human cell lines (HeLa, colon carcinoma HCT116 and RKO, and ovarian carcinoma A2780 cells). In this limited survey, high HuR levels correlated loosely with low miR-519 levels, supporting the notion that miR-519 could contribute broadly to reducing HuR abundance. Transfection of HCT116 and RKO cells with (AS)miR-519 elevated HuR levels, while (Pre)miR-519 lowered HuR levels (Fig. 1E). The effect of miR-519 in A2780 cells was studied similarly, but included a comparison with HOSE-B, an immortal but noncancerous line derived from ovarian epithelium that expressed much lower levels of HuR (Fig. 1F). Despite ≈12-fold higher HuR levels in A2780 cells, both cell types expressed comparable HuR mRNA levels, as determined by reverse-transcription (RT) followed by quantitative (q)PCR analysis (Fig. 1G, Left). Supporting a role for miR-519 in repressing HuR expression, miR-519 levels were markedly lower in A2780 cells (Fig. 1G, Right). In both cell lines, transfection of (AS)-miR-519 and (Pre)miR-519 elevated and reduced HuR levels, respectively. In sum, in multiple human cultured cell lines, miR-519 levels correlate inversely with HuR expression, miR-519 overexpression reduces HuR levels, and miR-519 reduction elevates HuR abundance.

miR-519 Represses HuR Translation.

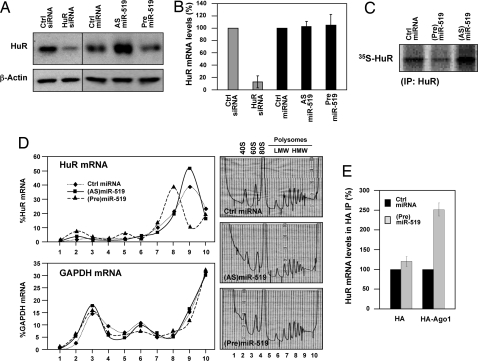

To understand the molecular process whereby miR-519 inhibits HuR expression, we investigated whether miR-519 reduces HuR mRNA levels. We compared miR-519 effects to those observed after transfection of a small interfering (si)RNA that efficiently lowered HuR abundance (Fig. 2A). As anticipated, HuR-targeting siRNA (gray bars) strongly reduced HuR mRNA levels when compared with Ctrl siRNA-transfected cells; by contrast, miR-519 reduction (AS) or overexpression (Pre) had no significant influence on HuR mRNA levels relative to Ctrl miRNA (black bars, Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Influence of miR-519 on HuR expression. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs or miRNAs; 48 h later, the levels of HuR and loading control β-actin were assessed by Western blotting (A) and the levels of HuR mRNA and normalization control 18S rRNA were quantified by RT-qPCR (B). (C) De novo HuR biosynthesis, as assessed by HuR IP 48 h after transfection of the indicated small RNAs (details in Materials and Methods). (D) Cells that were transfected as described in C were fractionated through sucrose gradients and the relative distribution of HuR mRNA (and housekeeping GAPDH mRNA) was studied by RT-qPCR analysis of RNA in each of 10 gradient fractions; 40S and 60S, small and large ribosome subunits, respectively; 80S, monosome; LMW and HMW, low- and high-molecular weight polysomes, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (E) HeLa cells were cotransfected with plasmids (expressing either HA or HA-Ago1) and with either Ctrl miRNA or (Pre)miR-519; 48 h later, the association of HuR mRNA with HA-Ago1 was assessed in IP samples prepared using anti-HA antibody. The levels of housekeeping UBC mRNA served to normalize sample input.

Instead, miR-519 was found to influence HuR translation, as measured using two experimental approaches. First, nascent HuR translation was measured by a brief (15-min long) incubation of HeLa cells with L-[35S]methionine and L-[35S]cysteine, after which HuR was subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) and the incorporation of radiolabeled amino acids visualized by autoradiography. As shown, relative to Ctrl miRNA cells, de novo HuR translation was lower (≈40%) in (Pre)miR-519-transfected cells and was higher (≈200%) in (AS)miR-519-transfected cells (Fig. 2C). The de novo synthesis of a housekeeping protein was unaltered (data not shown). Second, we investigated whether miR-519 levels affected the translation of HuR by monitoring the fraction of HuR mRNA associated with the translational machinery in each transfection group. Cytoplasmic extracts from the Ctrl miRNA, (AS)miR-519, and (Pre)miR-519 groups were fractionated on sucrose gradients and the relative abundance of HuR mRNA in each fraction was used to measure the association of HuR mRNA with the translational apparatus. As shown in Fig. 2D, HuR mRNA levels were very low in nontranslating and low-translating fractions of the gradient (fractions 1–7). In the Ctrl miRNA population, HuR mRNA was found in the actively translating fractions of the gradient (fractions 8–10); in this section of the gradient, HuR mRNA in (Pre)miR-519-transfected cells showed a leftward shift, indicating that HuR mRNA associated with smaller polysomes and further suggesting that miR-519 suppressed the initiation of HuR translation. By contrast, in (AS)miR-519-transfected cells, the peak of HuR mRNA was aligned with that seen in the Ctrl miRNA group, but a larger proportion of HuR mRNA was found in the actively translating fractions, suggesting that more HuR mRNA transcripts were engaged in translation. These differences were not seen when testing the distribution of the housekeeping GAPDH mRNA among the three groups.

Further evidence that HuR translation was repressed by miR-519 was gained from experiments that measured the influence of miR-519 on the association of HuR mRNA with the RISC complex. HeLa cells were cotransfected with either Ctrl miRNA or (Pre)miR-519 along with plasmids that expressed HA-tagged Ago1 or Ago2; 48 h later, the association of HuR mRNA with RISC was measured by HA-Ago1 IP followed by RT-qPCR amplification of HuR mRNA in the IP material. Moreover, (Pre)miR-519 transfection led to an increase in the association of HuR with HA-Ago1. Unexpectedly, no HuR mRNA was amplified from HA-Ago2 IP (data not shown). Collectively, these findings indicate that miR-519 represses HuR translation.

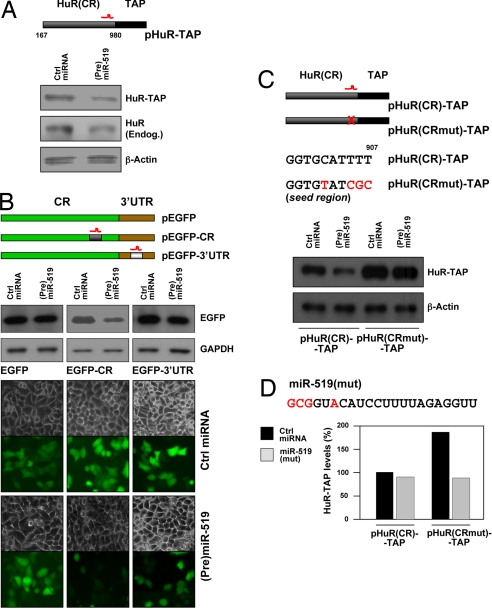

miR-519 Regulates Heterologous Reporters Containing HuR mRNA miR-519 Binding Sites.

To investigate whether miR-519 repressed HuR translation through the predicted target sites on the HuR CR and/or 3′-UTR, we studied the influence of miR-519 on reporter constructs bearing segments of the HuR mRNA. The putative influence of the CR site was initially tested by examining the expression of HuR-TAP, a chimeric protein encoded by a transcript that lacked the HuR 3′-UTR (13). As shown in Fig. 3A, transfection of (Pre)miR-519 reduced the levels of both the endogenous HuR protein and the ectopic HuR-TAP, suggesting that the miR-519 site on the HuR CR was indeed functional. This possibility was further tested by inserting the putative miR-519-directed sequence in the HuR CR within the EGFP reporter; similarly, the HuR 3′-UTR sequence that was predictedly targeted by miR-519 was placed in the 3′-UTR of EGFP (Fig. 3B). The heterologous EGFP reporters bearing no predicted miR-519 sites (EGFP), the HuR CR miR-519 site (EGFP-CR), or the HuR 3′-UTR miR-519 site (EGFP-3′-UTR) were tested in the presence of either Ctrl miRNA or (Pre)miR-519. By Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B), miR-519 overexpression had no influence on EGFP expression, modestly reduced EGFP-3′-UTR levels (to ≈70% of the levels seen in the Ctrl miRNA group), but strongly reduced EGFP-CR levels (to ≈30% of the levels seen in the Ctrl miRNA group). EGFP mRNA levels (with or without HuR mRNA sequences) remained unchanged between transfection groups (data not shown). These findings were verified by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

miR-519 influence on HuR reporter constructs. (A) Plasmids pHuR-TAP (expressing the HuR CR linked to a TAP tag) or control pTAP were cotransfected with Ctrl miRNA or (Pre)miR-519; the levels of endogenous HuR (Endog.) and the ectopic protein HuR-TAP were then analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Schematic of EGFP reporter constructs bearing either no HuR mRNA sequences (pEGFP), the miR-519 target site on the HuR CR (pEGFP-CR), or the miR-519 target site on the HuR 3′-UTR (pEGFP-3′-UTR); 48 h after cotransfection of the plasmids with Ctrl miRNA or (Pre)miR-519, the levels of EGFP expressed in each transfection group were analyzed by Western blotting and fluorescence microscopy. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (C Upper) Schematic of the predicted miR-519 binding site on the HuR CR; [pHuR(CR)-TAP], plasmid with the wild-type sequence; [pHuR(CRmut)-TAP], plasmid with four mutations in the miR-519 seed region. (Lower), Western blot analysis of GFP expression 48 h after cotransfection of pHuR(CR)-TAP or pHuR(CRmut)-TAP along with either Ctrl miRNA or (Pre)miR-519. (D) Top, miR-519(mut) depicting compensatory base changes (red) to restore binding to the mutated HuR(CR)-TAP mRNA. Plasmids pHuR(CR)-TAP and pHuR(CRmut)-TAP were cotransfected with either Ctrl miRNA or miR-519(mut); graph, quantification of representative HuR-TAP signals (Fig. S5).

Finally, the preferential repression through the HuR CR miR-519 site was also evaluated by mutating the seed region in the HuR-TAP reporter (Fig. 3C). Compared with the efficient repression of wild-type HuR(CR)-TAP by (Pre)miR-519, mutation of the seed region both increased the basal levels of HuR(CRmut)-TAP made this construct refractory to (Pre)miR-519-mediated repression (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4). To further confirm that the effects seen were due to miR-519, rescue experiments were performed. Transfection with miR-519(mut), which carried compensatory mutations, efficiently repressed pHuR(CRmut)-TAP levels but did not affect the levels of pHuR(CR)-TAP (Fig. 3D, Fig. S5). Taken together, these experiments indicate that the HuR mRNA has two sites through which miR-519 represses HuR expression, but the CR site has a stronger repressive influence.

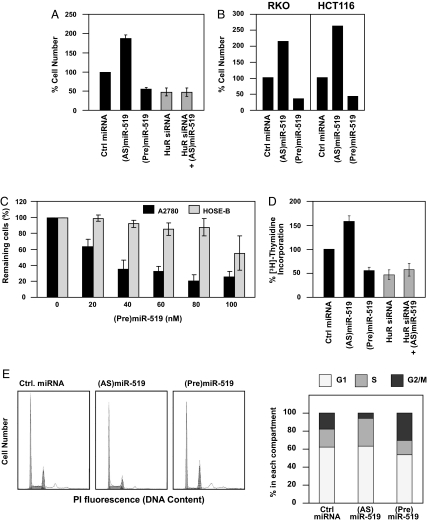

HuR Mediates the Effect of miR-519 on Cell Division.

Since HuR promotes the expression of many proteins implicated in the cell division cycle [including cyclin B1 and other cyclins (Fig. S6 and refs. 4, 16, 18)], we studied the influence of miR-519-modulated HuR on cell proliferation. First, the effect of reducing and elevating miR-519 on cell number was studied by monitoring cell numbers. (AS)miR-519-transfected HeLa population, expressing higher HuR (Fig. 1), showed elevated numbers of cells compared with the Ctrl miRNA population, while transfection of (Pre)mir-519 reduced HuR and lowered cell numbers (Fig. 4A). Importantly, the (AS)miR-519-triggered increase in cell numbers were specifically dependent on HuR, as concomitant HuR silencing by siRNA in cells transfected with (AS)miR-519 completely prevented the (AS)miR-519-elicited proliferation. These effects of miR-519 on cell number were not restricted to HeLa cells, as RKO and HCT116 cells showed similar changes following modulation of miR-519 abundance (Fig. 4B) and affected ovarian cancer cells more strongly than untransformed ovarian epithelial cells (Fig. 4C). Testing the influence of miR-519 upon [3H]-thymidine incorporation, which quantifies DNA replication, further showed that the growth-promoting action of (AS)miR-519 depended on the heightened HuR levels (Fig. 4D). This effect was additionally studied by analyzing the cell cycle distribution profiles of cells expressing different levels of miR-519. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that (AS)miR-519-transfected cells had the largest proportion of S-phase cells and the smallest G2/M compartment (Fig. 4E). Conversely, (Pre)miR-519 cells had the smallest S-phase component and the largest G2/M population; the latter effect could be due to the fact that there was insufficient cyclin B1 to exit G2/M, leading to a lengthening of this cell cycle phase. Together with the changes in DNA replication and cell cycle distribution profiles, these results indicate that the miR-519-elicited changes in cell proliferation are mediated through the influence of miR-519 on HuR levels.

Fig. 4.

Influence of miR-519-regulated HuR on cell proliferation. (A) By 48 h after transfection of HeLa cells with the siRNAs and miRNAs shown, cell numbers were measured using a hemocytometer and represented as percentage of cells relative to the Ctrl miRNA group. (B) RKO and HCT116 cells were transfected as indicated; cell numbers were quantified 48 h later as explained in A. (C) Influence of (Pre)miR-519 on the viability of ovarian cancer cells (A2780) and ovarian epithelial cells (HOSE-B) 48 h after transfection with increasing doses of (Pre)miR-519, as quantified using the MTT assay. (D) Measurement of [3H]-thymidine incorporation by 48 h after transfection of HeLa cells with the siRNAs and miRNAs indicated. The data in panels A, C, and D are the means ± SD from three experiments. (E) Forty-eight h after transfection with Ctrl miRNA, (AS)miR-519, or (Pre)miR-519, HeLa cells were subjected to FACS analysis (Left) and the relative G1, S, and G2/M compartments calculated (Right). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

We describe the repression of HuR expression by miR-519. Our findings indicate that miR-519 reduces HuR translation and not HuR mRNA levels or stability, since miR-519 overexpression specifically lowered HuR nascent translation and miR-519 inhibition elevated it. Through the use of ectopic reporters, the miR-519 site on the HuR CR appeared to be the predominant site through which miR-519 elicited the repression of HuR translation (Fig. 3). These observations differ from the more common finding that miRNAs exert their regulatory actions through the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs. Here, the lesser effect of reporters bearing the HuR 3′-UTR miR-519 site (Fig. 3B) suggests that this site is not extensively used. With a CR-encoded miR-519 site, several models of miRNA-mediated repression of translation can be envisioned (as described in ref. 28). Besides repressing the initiation of translation, the inhibition of translation elongation and the early termination by ribosome drop-off are well suited to explain our findings, particularly since the rate of nascent HuR translation varied markedly after altering miR-519 levels, while the distribution of HuR mRNA on polysome gradients varied little (Fig. 2D).

By reducing HuR protein levels, miR-519 indirectly lowers the expression of HuR target mRNAs, many of which encode proliferative proteins, such as cyclins, growth factors, and mitogenic transcription factors (4, 13, 16). The effect of miR-519 thus recapitulates the growth inhibition that was observed after reducing HuR levels in models of cell cycle progression and replicative senescence (16, 29, 30). Conversely, inhibition of miR-519 function elevated HuR levels and enhanced cell division, as seen in culture systems in which HuR is overexpressed or is elevated endogenously (16, 30). Whether miR-519 represses the expression of other proliferative proteins (e.g., proteins implicated in cell division or the response to mitogenic signals), remains to be elucidated. However, the increased cell proliferation seen after lowering miR-519 was strongly dependent on the heightened HuR abundance, since it was abolished when HuR was silenced by RNAi (Fig. 4 A and D). These observations suggest that HuR is a major effector of the growth suppressive action of miR-519.

One interesting facet of this study is that it describes an example of one type of posttranscriptional regulator (a miRNA) controlling the expression of another type of posttranscriptional regulator (an RBP). Previous reports showed that some TTR-RBPs can modulate posttranscriptionally the expression of other TTR-RBPs (3, 31); the present study provides a prominent example of a miRNA regulating a TTR-RBP. The fact that HuR enhances the stability of many target mRNAs raises an intriguing possibility for further consideration: if miR-519 is found to trigger the decay of a putative target mRNA, it is possible that the effect is indirect, should HuR be a stabilizing TTR-RBP for that particular mRNA. In broad terms, our findings advise caution as to the mRNA-destabilizing function of some miRNA–mRNA interactions, since they could arise from an indirect, repressive influence of the miRNA upon a stabilizing TTR-RBP.

The discovery that lowering miR-519 confers growth advantage raises the possibility that HuR/miR-519 regulatory axis could enhance the growth of malignant cells. Such a role was previously proposed for HuR, because HuR targets include mRNAs encoding proteins that promote proliferation and angiogenesis, and proteins that enhance the cell's ability to evade senescence, apoptosis, and the immune system (8). In light of the influence of miR-519 on HuR, studies are warranted to test whether miR-519 expression is broadly reduced in cancer. Several oncogenic miRNAs (oncomirs) have been identified (32); however, the discovery of miR-519 was relatively recent, so its function remains virtually unknown. As these studies progress, it will be important to perform a systematic analysis of miR-519 levels in tumor collections. Ongoing work is aimed at elucidating endogenous target mRNAs for miR-519 by using a tagged miR-519 bait. Other studies are underway to test whether miR-519 levels affect tumor growth in mice and whether such influence is dependent on HuR. Should miR-519 specifically reduce tumor growth, perhaps coining a term to refer to tumor suppressor miRNAs, e.g., “ts-miRs,” will be necessary. In closing, through its influence on HuR, miR-519 affects gene expression programs directly by acting upon miR-519 target mRNAs, and indirectly through its action of HuR and hence its posttranscriptional targets. This interaction illustrates the complexity of posttranscriptional regulatory networks that control the rate of cell division.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Analysis of Cell Proliferation.

Human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM containing 5% FBS. HCT116 colon cancer cells were in McCoy's 5A (+10% FBS), colon carcinoma cells RKO (minimum essential medium + 10% FBS) A21780 and HOSE-B cells were cultured in RPMI. All cultures were supplemented with antibiotics. Cells (≈50% confluence) were transfected using oligofectamine (Invitrogen) with 100 nM small RNAs (Ambion): HuR siRNA, control miR, (Pre)miR-519 (designed to express UUGGAGAUUUUCCUACGUGAAA), (AS)miR-519 (UUUCACGUAGGAAAAUCUCCAA), and miR-519(mut) (GCGGUACAUCCUUUUAGAGGUU). Plasmids (expressing HA, HA-Ago1, EGFP, TAP, or HuR-TAP) were transfected using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen); 48 h later protein and RNA analyses were performed. DNA replication was assessed by measuring [3H]-thymidine incorporation as described (21). Cell cycle analysis was performed on propidium iodide-stained, ethanol-fixed cells using Multicycle software; MTT analysis was performed using standard procedures.

Protein Analysis.

Whole-cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer, resolved and transferred as described (21). Incubations with primary mouse monoclonal antibodies recognizing HuR, α-Tubulin, nucleolin, cyclin B1 (all from Santa Cruz), β-actin (Abcam) or pVHL (Neo-Markers) were followed by incubations with the appropriate secondary antibodies (Amersham) and by detection using enhanced luminescence (Amersham).

Nascent (de novo) translation of HuR was studied as described (21) and SI Text.

RNA Analysis.

Total cellular RNA was prepared directly from cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen) or was isolated after immunoprecipitation (IP) from cellular RNA-protein complexes by IP [using anti-HuR, anti-HA or IgG, as described (21, 33)]. After reverse transcription (RT) using random hexamers and SSII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), real-time quantitative (q)PCR analysis was performed using gene-specific primer pairs (Table S1) and SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), as described (21). Mature miR-519 (Table S2) was quantified using Taqman microRNA detection assay (Applied Biosystems).

Polyribosome Fractionation.

Cells were incubated with cycloheximide (Calbiochem; 100 μg/ml, 15 min) and cytoplasmic lysates (500 μl) were fractionated by centrifugation through 10–50% linear sucrose gradients and divided into 10 fractions for RT-qPCR analysis, as described (21).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are grateful to P. J. Morin (National Institute on Aging, NIA) for providing cell lines and to R. Wersto and his team for assistance with flow cytometry. This research was supported entirely by the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the NIA, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0809376106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Keene JD. RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore MJ. From birth to death: the complex lives of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science. 2005;309:1514–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.1111443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pullmann R, Jr., et al. Analysis of turnover and translation regulatory RNA-binding protein expression through binding to cognate mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6265–6278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00500-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdelmohsen K, et al. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by RNA-binding proteins during oxidative stress: implications for cellular senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389:243–255. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdelmohsen K, Lal A, Kim HH, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional orchestration of an anti-apoptotic program by HuR. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1288–1292. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.11.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherry J, Karschner V, Jones H, Pekala PH. HuR, an RNA-binding protein, involved in the control of cellular differentiation. In Vivo. 2006;20:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorospe M. HuR in the mammalian genotoxic response: post-transcriptional multitasking. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:412–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López de Silanes I, Lal A, Gorospe M. HuR: post-transcriptional paths to malignancy. RNA Biol. 2005;2:11–13. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.1.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López de Silanes I, Zhan M, Lal A, Yang X, Gorospe M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2987–2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CY, Xu N, Shyu A-B. Highly selective actions of HuR in antagonizing AU-rich element-mediated mRNA destabilization. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7268–7278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7268-7278.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazan-Mamczarz K, et al. RNA-binding protein HuR enhances p53 translation in response to ultraviolet light irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8354–8359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432104100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lal A, Kawai T, Yang X, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Gorospe M. Anti-apoptotic function of RNA-binding protein HuR effected through prothymosin α. EMBO J. 2005;24:1852–1862. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galbán S, et al. RNA-binding proteins HuR and PTB promote the translation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:93–107. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00973-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullmann M, Gopfert U, Siewe B, Hengst L. ELAV/Hu proteins inhibit p27 translation via an IRES element in the p27 5′UTR. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3087–3099. doi: 10.1101/gad.248902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Caldwell MC, Lin S, Furneaux H, Gorospe M. HuR regulates cyclin A and cyclin B1 mRNA stability during cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2000;19:2340–2350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan XC, Steitz JA. HNS, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling sequence in HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15293–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HH, et al. Nuclear HuR accumulation through phosphorylation by Cdk1. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1804–1815. doi: 10.1101/gad.1645808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doller A, et al. Protein kinase C alpha-dependent phosphorylation of the mRNA-stabilizing factor HuR: implications for posttranscriptional regulation of cyclooxygenase-2. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2137–2148. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doller A, et al. Posttranslational modification of the AU-rich element binding protein HuR by protein kinase Cdelta elicits angiotensin II-induced stabilization and nuclear export of cyclooxygenase 2 mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2608–2625. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01530-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelmohsen K, et al. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Mol Cell. 2007;25:543–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazroui R, et al. Caspase-mediated cleavage of HuR in the cytoplasm contributes to pp32/PHAP-I regulation of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:113–127. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osada H, Takahashi T. MicroRNAs in biological processes and carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2–12. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutvagner G, et al. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eulalio A, Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Getting to the root of miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2008;132:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atasoy U, Watson J, Patel D, Keene JD. ELAV protein HuA (HuR) can redistribute between nucleus and cytoplasm and is upregulated during serum stimulation and T cell activation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:3145–3156. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.21.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W, Yang X, Cristofalo VJ, Holbrook NJ, Gorospe M. Loss of HuR is linked to reduced expression of proliferative genes during replicative senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5889–5898. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5889-5898.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai T, et al. Translational control of cytochrome c by RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and HuR. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3295–3307. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3295-3307.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs: microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lal A, et al. p16(INK4a) translation suppressed by miR-24. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.