Abstract

Chronic stress impairs spatial memory and alters hippocampal structure, which are changed in the opposite direction following enriched environment (EE). Therefore, this study incorporated these two paradigms to determine whether EE would prevent chronic stress from impairing spatial learning and memory. Young adult male rats were housed in EE for one week prior to and throughout three weeks of daily restraint stress. On the day after the end of restraint, rats were trained and tested on either a water maze (19° or 24° C water temperature) or a spatial recognition Y-maze (4-hour and 1-minute delay between training and testing). Chronically stressed rats housed in standard conditions showed impaired acquisition on the 19°C version of the water maze and deficits on the 4-hour delay version of the Y-maze. Chronically stressed rats housed in EE, however, showed intact performance on all tasks. All rats showed intact performance on the 24°C version of the water maze and on water maze probe trials for both versions. The results showed that EE in adulthood prevented spatial learning and memory impairment in chronically stressed rats, indicating that the context of stress exposure impacts susceptibility to chronic stress-induced cognitive deficits.

Keywords: Environmental enrichment, Morris water maze, Y-maze, restraint, Water temperature, Stress, Reference memory

Introduction

Chronic stress produces changes in the hippocampal morphology of rats and primates. These alterations include retraction of the apical dendrites in the CA3 region of the hippocampus following prolonged restraint [9, 17, 33] or chronic social stress [18]. Chronic stress can also modify hippocampal dendritic spine number and shape [11, 19, 30]. Prolonged stressful periods can result in cell death [31]. Collectively there is clear evidence that chronic stress can significantly alter hippocampal structure.

Many of these structural changes in the hippocampus following chronic stress are thought to contribute to impaired hippocampal function, such as spatial learning and memory. Three weeks of daily restraint impairs spatial memory in male rats tested on the eight-arm radial maze [16] and the Y-maze [7, 8, 36, 37]. Housing rats with different cage mates each day combined with five weeks of cat exposure hinders performance on a radial arm water maze [25]. Twelve weeks of daily cold water immersion also impairs spatial memory on the eight –arm radial maze [23]. The wide range of stressors and spatial memory tasks show that chronic stress impairs spatial learning and memory.

In contrast to the effects of chronic stress, enriched environment (EE) produces opposite effects on hippocampal structure and function. EE improves memory [14, 24, 32, 34, 35] and hippocampal structure and chemistry [For review, see 21, 28] in aged animals and animals with brain damage. EE also prevents stress-induced learning and memory impairments [10]. In particular, EE prevents the detrimental effects of postnatal stress on learning and memory in adulthood. Another report shows that acute stress leaves spatial learning intact in EE rats, while impairing the learning of control rats in the Morris water maze [15]. These findings indicate that EE may be used to prevent the impairing effects of postnatal or acute stress on mnemonic processes.

The purpose of the current study was to test the hypothesis that EE can prevent chronic stress-induced spatial learning and memory deficits in rats that were exposed to both EE and chronic stress as adults. Adult male rats were restrained daily, housed in EE or standard environments and tested on a spatial recognition memory version of the Y-maze or Morris water maze using two water temperatures (19°C or 24°C). Different water temperatures were used because 19°C water leads to greater release of the stress hormone, corticosterone, compared to 25°C water [29], and elevated levels of corticosterone impact performance in rats that have undergone hippocampal lesion [27] or chronic stress [37]. Specifically, rats that have undergone hippocampal lesions [27] or chronic stress [37] showed spatial memory impairments, which were blocked with the corticosterone synthesis inhibitor metyrapone. Therefore, 19 and 24°C water temperatures were used in this study to increase the likelihood that chronic stress-induced spatial learning and memory deficits could be detected.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Fifty-four male, Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, 300 g) were housed on a 12/12 light-dark cycle as specified in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Science, National Research Council, 1996). All manipulations occurred during the dark phase of the light cycle.

Housing Conditions

Rats were placed in either standard housing (STD, pair housed in Plexiglas cages – 20 × 46 × 18cm) or EE. EE protocols vary widely among labs [for review, see 13] and the enrichment protocol employed here was chosen to be within the range of the various protocols with regard to number of rats per cage, cage size, items within the cage and frequency with which the items were changed. EE consisted of 6 rats per Plexiglas cage (74 × 91 × 36cm), which contained movable (small PVC fittings, nesting material) and immovable objects (tunnels, running wheels, and pots). Objects were changed three times a week. EE began when the animals arrived and continued throughout the experiment, which lasted 30-31 days.

Chronic Stress

The restraint paradigm began one week after the rats arrived and were assigned to housing conditions. Rats were restrained in wire mesh for 6 hours a day for 21 days and were weighed weekly [for details, 36]. STD rats were returned to their home cages during restraint, while EE rats were placed in standard cages in chambers shared with stressed, STD rats during restraint. Restrained rats were never in the same housing chamber with non-stressed rats. EE and chronic stress treatments resulted in three separate groups (n = 6/group for each behavioral task): non-stressed rats housed in standard conditions (CON-STD); chronically stressed rats housed in standard conditions (STR-STD) and chronically stressed rats housed in enriched conditions (STR-EE). Behavioral assessment began on the day after restraint ended.

Water maze

The Morris water maze protocol was adapted from [5] and consisted of a blue circular tank (183cm diameter) in a room that was rich with spatial cues. The tank contained a black circular platform (13cm diameter) submerged under 2cm of water, which was dyed with black nontoxic tempura paint. Separate groups of rats were tested on 19°C and 24°C versions. Training consisted of four trials per day for three days. During training, a rat was started at one of four locations, which differed for each trial on each day. Each trial lasted 60 seconds or until the rat reached the platform. The rat was allowed to stay on the platform for 15 seconds before being dried off and transferred to a heated holding cage. If the rat did not reach the platform within 60 seconds, it was guided there by the experimenter. The inter-trial interval was 10 minutes. Forty-five minutes after the final training trial on day 3, the platform was removed and the rats were given a 60 second probe trial. For the probe trial the water maze was conceptually divided into four equal quadrants including the quadrant where the platform was previously located, referred to as the target quadrant, and the quadrant directly across from the target quadrant, referred to as the opposite quadrant. For the probe trial, time spent and distance traveled were compared between the target and opposite quadrants.

Y-maze

The Y-maze was previously described [7, 37] and consisted of three identical arms made of black Plexiglas and multiple extra-maze cues. The three arms were designated Novel, Start, and Other, and were counterbalanced among rats. On the 1st and 2nd days following the end of chronic restraint, rats were tested on the Y-maze using 4-hour and 1-minute delays, respectively. During training, one arm (Novel) was blocked, allowing rats to explore the Start and Other arms for 15 minutes. Following training, rats were returned to their home chambers (4-hour delay) or placed in their home cage outside the testing room (1-minute delay). After the delay, the mazes were switched so that intra-maze cues could not be used. Rats were then returned to the same start location used during training, and allowed to explore all three arms for five minutes. Rats were interpreted to have intact spatial memory if they showed a preference for the Novel arm since rats have an innate tendency to explore novelty. Behavior was scored to determine the number of entries made (Entry) and time spent (Dwell) in the three arms. An entry was counted when the rat’s forearms entered an arm. Entry and Dwell data were converted into percentages and the sum of entries into all arms (total entries), were computed to determine whether activity levels were similar among groups.

Data analysis

Parametric data were analyzed by ANOVA and significant main effects and interactions were investigated further with Neuman-Keuls post hoc tests or planned comparisons. Nonparametric data were analyzed by Wilcoxon analyses.

Results

19°C water maze

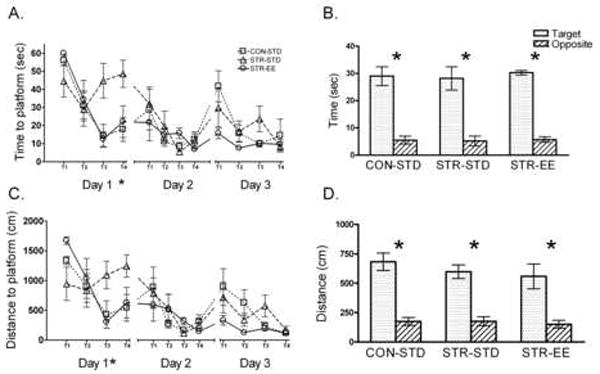

Rats in all groups showed a significant reduction in time to reach the platform location across days and trials; however, STR-STD rats showed impaired acquisition. For training day 1, a mixed factors ANOVA (Group × Trial) for time to reach the platform revealed a significant effect of Trial, F(3, 45)=11.58, p<0.001 and a significant interaction between Group and Trial, F(6, 45)=3.94, p<0.01 (main effect of group, n.s.). Planned comparisons revealed that for trials 3 and 4 on day 1, STR-STD rats took longer to reach the platform than CON-STD or STR-EE rats (Fig 1, p<0.05). For days 2 and 3, mixed factors ANOVA (Group × Trial) failed to show any significant Group differences.

Fig. 1.

STR-STD rats were impaired on day 1 of training in the 19°C version of the water maze while STR-EE rats showed intact performance. Overall, rats in all groups showed reduced times and distances to the platform across trials and days. A) Time acquisition: STR-STD rats took longer to locate the hidden platform on trials 2 and 3 on day 1 than CON-STD or STR-EE rats. B) Time probe: All rats performed similarly on the probe trial, spending more time in the target quadrant than the opposite quadrant. C) Distance acquisition: STR-STD rats tended to swim further to locate the hidden platform on trials 2 and 3 on day 1 than CON-STD or STR-EE. D) Distance probe: All rats performed similarly on the probe trial, covering more distance in the target quadrant than the opposite quadrant. The probe data support the interpretation that the rats used a spatial strategy since a motor strategy would lead to concentric circles in the pool and similar amounts of time in all quadrants. *p < 0.05 for interaction between Group and Trial.

The distance analyses were consistent with the analyses for latency. For distance to reach the platform, the mixed factors ANOVA for Group and Trial on day 1 revealed a significant effect of Trial, F(3, 45)=5.94, p<0.001 and a significant interaction between Group and Trial, F(6, 45)=3.34, p<0.01. Planned comparisons for trials 3 and 4 on day 1 revealed that STR-STD rats swam further to reach the platform than CON-STD rats on trial 4 or STR-EE rats on trial 3 (p<0.05). For days 2 and 3, mixed factors ANOVA (Group × Trial) failed to show any significant Group differences for swim distance.

During the probe trial on day 3, all groups showed similar performance. A 3 × 2 mixed factors ANOVA (Group × Quadrant) for swim time in the target vs. opposite quadrant revealed that all groups spent more time in the target vs. the opposite quadrant, F(1, 15)=93.03, p<0.001. Distance data were consistent with the latency analysis and showed that all groups swam greater distance in the target quadrant compared to the opposite quadrant, F(1, 15)= 64.38, p<0.001 (Fig. 1B & 1D).

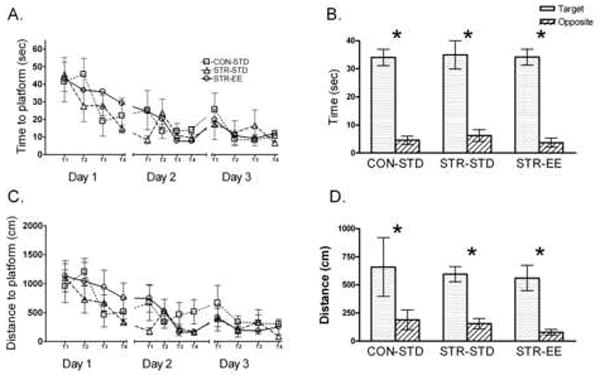

24°C water maze

Rats in all groups showed reduced latency and distance to the platform across trials with null treatment main effects and interactions. There was a significant effect of Day, F(2, 30)=24.24, p<0.001 and Trial, F(3, 45)=10.70, p<0.001 for time to reach the platform and a significant effect of Day, F(2, 30)=26.34, p<0.001 and Trial, F(3, 45)=10.90, p<0.001 for distance to reach the platform. The latency and distance to reach the platform decreased across days and trials for all groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

All groups showed similar performance on the 24°C version of the water maze with reduced times and distances to the platform across days and trials. A) Time acquisition: All groups showed similar times to the platform location. B) Time Probe: All groups performed similarly on the probe trial, spending more time in the target quadrant than the opposite quadrant. C) Distance acquisition: All groups showed similar distances to the platform location. D) Distance probe: All groups performed similarly on the probe trial swimming more distance in the target quadrant than in the opposite quadrant.

During the probe trial on day 3, all groups showed similar performance by preferring the target quadrant. A 3 × 2 mixed factors ANOVA (Group × Quadrant) for swim time in the target vs. opposite quadrant revealed similar performance among groups with all groups showing greater swim time in the target vs. the opposite quadrant, F(1, 15)=99.43, p<0.001. Distance data also revealed a greater swim distance in the target quadrant compared to the opposite quadrant, F(1, 15)= 97.11, p<0.001 (Fig. 2B & 2D).

Y-maze

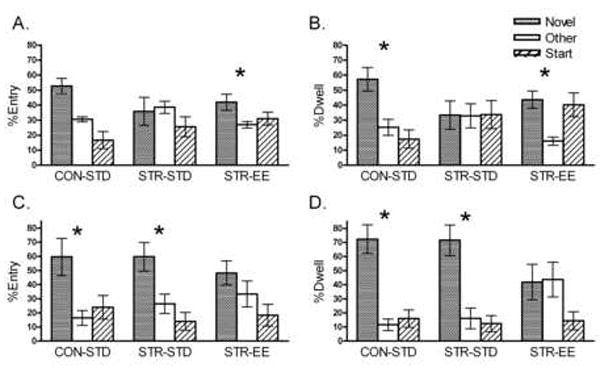

Rats habituate to the Y-maze quickly, showing reduced activity as indicated by fewer entries across minutes. Therefore, a mixed factors ANOVA for Group × Minute was performed on total entries made into all arms during the 4-hour delay version, revealing a significant effect of Minute, F(4, 60)=12.43, p<0.001. Post hoc comparisons revealed that rats entered more arms during minute 1 than minutes 2-5 (p<0.001), indicating that the rats explored more during minute 1 than during minutes 2-5. Therefore, minute 1 was used for the Y-maze analyses.

In the 4-hour delay version of the Y-maze, STR-STD rats showed impaired novel arm preference while STR-EE and CON-STD showed intact novel arm preference. Wilcoxon tests for %Entry into the Novel vs. Other arm revealed that STR-STD rats entered the Novel and Other arms similarly (p=0.86), while STR-EE rats entered the Novel arm more than the Other arm (p<0.05). CON-STD rats appeared to enter the Novel arm more than the Other arm but the analysis failed to reach significance (p=0.10, Fig. 3A). For time spent in each arm (%Dwell), STR-STD rats spent similar amounts of time in the Novel and Other arms (p=0.91) while CON-STD and STR-EE spent more time in the Novel arm vs. Other arm (p<0.05, Fig. 3B). Analysis of total entries during minute 1 revealed that all groups had a similar number of total entries F(2, 15)=.89, p=0.42 (data not shown). In the 1-minute delay version of the Y-maze, CON-STD and STR-STD rats showed greater %Entry and %Dwell in the Novel vs. Other arm (p<0.05). STR-EE rats, however showed similar %Entry and %Dwell in the Novel arm compared to the Other arm (Fig’s. 3C & 3D).

Fig. 3.

STR-STD rats were impaired in the Y-maze at a 4-hour delay while STR-EE rats showed intact performance. A) %Entry 4-hour delay: STR-STD entered the Novel and Other arms similarly while STR-EE rats entered the Novel arm more than the Other arm. B) %Dwell 4-hour delay: STR-STD rats showed impaired performance by spending similar amounts of time in the Novel and Other arms, while STR-EE rats spent more time in the Novel arm than the Other arm. Since the STR-STD rats consistently performed poorly on both measures, they were interpreted to show impaired performance. STR-EE rats, however, performed well on both measures, indicating intact spatial memory. C) % Entry 1-minute delay: CON-STD and STR-STD rats entered the Novel arm more than the Other arm, indicating motivation to explore novelty. The Novel arm may no longer have been of interest to the STR-EE rats after the first test and the fact that they showed Novel arm preference on the 4-hour version indicates that STR-EE rats can perform the task. D) % Dwell 1-minute delay: CON-STD and STR-STD rats spent more time in the Novel arm than the Other arm, indicating motivation to explore novelty. These data indicate that novelty-seeking was intact in STR-STD rats, therefore the impairment seen in the 4-hour delay version is unlikely to be attributed to reduced novelty-seeking behavior. *p < 0.05 for Novel vs. Other arm Wilcoxon analysis.

Body weight

STR rats, regardless of housing conditions, showed reduced body weight gain compared to CON-STD rats. A 3 × 5 mixed factors ANOVA for Group across days (1, 7, 14, 21, 28) revealed a significant effect of Group, F(2, 51)=17.45, p<0.001, a significant effect of Day, F(3, 153)=236.85, p<0.001 and a significant interaction between Group and Day, F(6, 153)=21.37, p<0.001. Post hoc tests showed that STR-STD and STR-EE rats gained weight more slowly than CON-STD rats. In addition, during the week before the start of restraint, when EE had already begun, a 2 × 2 mixed factors ANOVA for Housing Condition (STD, EE) and Day (1, 7) revealed that EE rats gained less weight than the STD: significant effect of Day, F(1, 52)=3.01, p<0.001 and a significant interaction between housing condition and Day, F(1, 52)=8.37, p<0.01 (data not shown).

Discussion

The data support the hypothesis that EE prevents chronic stress-induced spatial memory deficits. STR-STD rats showed impaired acquisition in the 19°C version of the water maze and impaired spatial memory on the Y-maze after a 4-hour delay and these impairments were prevented with EE. Chronic stress was perceived as stressful because STR-STD showed reduced weight gain, and reduced body weight in the STR-EE group began before the onset of restraint, which is consistent with other reports [22]. The combination of tasks and measures provide strong evidence that EE can prevent chronic stress-induced spatial memory impairments when initiated during adulthood. To our knowledge, this is the first report to show that EE prevents chronic stress-induced spatial learning and memory deficits when both EE and chronic stress are initiated in adulthood.

The results indicate that spatial strategies were used in the water maze and Y-maze. In the water maze, rats found the platform quickly by the end of training, indicating similar motivation/motor ability. While all groups showed learning, as indicated by reduced time and distance to the platform across trials, some rats could have potentially used a nonspatial strategy. However, varying the start locations across trials made turning strategies ineffective. Moreover, the probe trial revealed that rats used a direct spatial strategy by favoring the quadrant that contained the platform during training. If a nonspatial strategy had been used such as swimming in concentric circles at the correct fixed distance from the wall, rats would have spent similar amounts of time and swam similar distances in the target and opposite quadrants. For the Y-maze, all groups showed a similar number of total entries, indicating comparable motivation/motor ability. Additionally, the STR-STD rats showed Novel arm recognition after a 1-minute delay, indicating that they were capable of performing (showing Novel arm preference) when task demands were reduced. While the STR-EE rats did not show an arm preference after a 1-minute delay, the important finding is that they favored the novel arm in the more challenging 4 hour delay version, indicating functional spatial memory. Perhaps the STR-EE rats habituated quickly to the relatively modest novelty in the Y-maze given that they were repeatedly exposed to novelty in their home cages and had previously been tested on a 4 hour delay version. This interpretation is consistent with reports in which rats have high levels of exploration in the open field initially but habituate quickly [13, 15]. Overall these data support the interpretation that EE prevents chronic stress-induced spatial memory deficits.

The current findings differed between the 19°C and the 24°C versions of the water maze. The two versions were used because water temperature can influence the neural substrates that support spatial learning in the water maze, i.e. the amygdala is activated under cold, but not warm water conditions [1]. Colder water also leads to higher corticosterone levels than warmer water [29]. We have recently found that pharmacologically blocking stress-induced corticosterone release before training on the Y-maze can restore spatial memory in chronically stressed rats [37]. Perhaps the 19°C, but not the 24°C version, elevated corticosterone levels sufficiently to impair spatial learning, which may explain why spatial learning deficits were only observed in the cold water version. Interestingly, EE can decrease the corticosterone response to a stressor [2, 3], which may be a mechanism by which EE prevents spatial learning and memory deficits in chronically stressed rats.

These data add to the literature on the influence of EE on hippocampal plasticity and cognition following stress. Studies have previously shown that EE in adulthood can prevent memory deficits following acute stress and postnatal stress [10, 15, 38]. Other studies have shown that hippocampal plasticity as measured by long-term potentiation and long-term depression can be impacted by prenatal chronic stress and this impact can be prevented by EE during the early postnatal period [38]. Although the present research utilized EE and stress on very different timeframes than the other studies, our outcome was consistent with these other reports. The data considered together provide strong support for EE as a treatment to prevent the deleterious effects of stress during development and early adulthood.

The present data allow for two interpretations regarding the effects of EE on spatial ability in chronically stressed rats. First, EE may have prevented cognitive deficits by interacting with the mechanism(s) that caused spatial learning and memory impairments in chronically stressed rats. This hypothesis predicts that chronic stress and EE act on similar neurobiological substrates. Alternatively, STR-EE rats may have had enhanced spatial learning and memory compared to CON-STD rats if chronic stress had not been administered, bringing STR-EE rats to the level of CON-STD rats. This hypothesis predicts that chronic stress and EE work in parallel to influence spatial ability. Regardless of the interpretation, these data are the first results to our knowledge showing that EE in adulthood can prevent chronic stress-induced spatial learning and memory deficits.

The present findings are important and show that EE can influence cognitive outcomes following chronic stress. EE may negate the deficits produced by chronic stress on hippocampal-dependent spatial learning and memory tasks by altering many properties of the hippocampus. EE can increase hippocampal neurogenesis [6], dendritic spines [4] dendritic arborization [12], BDNF [26], and glucocorticoid receptors [20]. Any of these changes may serve to protect the hippocampus from challenges arising from chronic stress. As mentioned above EE may also prevent chronic stress-induced spatial learning and memory impairments through alterations of the HPA axis. Overall, the present data indicate that enhanced opportunities for mental and/or physical activity in adulthood may help overcome potential cognitive deficits induced by chronic stress. Future studies will investigate the neuroanatomical and neurochemical endocrinological mechanisms by which EE prevents spatial learning and memory deficits.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIH MH64727. We would also like to thank Dr. Heather Bimonte-Nelson, James Harman, Matthew Young, Juan Gomez, Gillian Hamilton and Shelli Dubbs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Akirav I, Sandi C, Richter-Levin G. Differential activation of hippocampus and amygdala following spatial learning under stress. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:719–25. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belz EE, Kennell JS, Czambel RK, Rubin RT, Rhodes ME. Environmental enrichment lowers stress-responsive hormones in singly housed male and female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;76:481–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benaroya-Milshtein N, Hollander N, Apter A, Kukulansky T, Raz N, Wilf A, Yaniv I, Pick CG. Environmental enrichment in mice decreases anxiety, attenuates stress responses and enhances natural killer cell activity. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1341–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman RF, Hannigan JH, Sperry MA, Zajac CS. Prenatal alcohol exposure and the effects of environmental enrichment on hippocampal dendritic spine density. Alcohol. 1996;13:209–16. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)02049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bimonte-Nelson HA, Francis KR, Umphlet CD, Granholm AC. Progesterone reverses the spatial memory enhancements initiated by tonic and cyclic oestrogen therapy in middle-aged ovariectomized female rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:229–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruel-Jungerman E, Laroche S, Rampon C. New neurons in the dentate gyrus are involved in the expression of enhanced long-term memory following environmental enrichment. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:513–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad CD, Galea LA, Kuroda Y, McEwen BS. Chronic stress impairs rat spatial memory on the Y maze, and this effect is blocked by tianeptine pretreatment. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:1321–34. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conrad CD, Grote KA, Hobbs RJ, Ferayorni A. Sex differences in spatial and non-spatial Y-maze performance after chronic stress. Neurobio Learn Mem. 2003;79:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(02)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad CD, LeDoux JE, Magariños AM, McEwen BS. Repeated restraint stress facilitates fear conditioning independently of causing hippocampal CA3 dendritic atrophy. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:902–13. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.5.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui M, Yang Y, Yang J, Zhang J, Han H, Ma W, Li H, Mao R, Xu L, Hao W, Cao J. Enriched environment experience overcomes the memory deficits and depressive-like behavior induced by early life stress. Neurosci Lett. 2006;404:208–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donohue HS, Gabbott PL, Davies HA, Rodriguez JJ, Cordero MI, Sandi C, Medvedev NI, Popov VI, Colyer FM, Peddie CJ, Stewart MG. Chronic restraint stress induces changes in synapse morphology in stratum lacunosum-moleculare CA1 rat hippocampus: a stereological and three-dimensional ultrastructural study. Neuroscience. 2006;140:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faherty CJ, Kerley D, Smeyne RJ. A Golgi-Cox morphological analysis of neuronal changes induced by environmental enrichment. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;141:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox C, Merali Z, Harrison C. Therapeutic and protective effect of environmental enrichment against psychogenic and neurogenic stress. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamm RJ, Temple MD, O’Dell DM, Pike BR, Lyeth BG. Exposure to environmental complexity promotes recovery of cognitive function after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 1996;13:41–7. doi: 10.1089/neu.1996.13.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson F, Winblad B, Mohammed AH. Psychological stress and environmental adaptation in enriched vs. impoverished housed rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:193–207. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00782-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luine V, Villegas M, Martinez C, McEwen BS. Repeated stress causes reversible impairments of spatial memory performance. Brain Res. 1994;639:167–70. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91778-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magariños AM, McEwen BS. Stress-induced atrophy of apical dendrites of hippocampal CA3c neurons: comparison of stressors. Neuroscience. 1995;69:83–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00256-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKittrick CR, Magarinos AM, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ, McEwen BS, Sakai RR. Chronic social stress reduces dendritic arbors in CA3 of hippocampus and decreases binding to serotonin transporter sites. Synapse. 2000;36:85–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200005)36:2<85::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaughlin KJ, Baran SE, Wright RL, Conrad CD. Chronic stress enhances spatial memory in ovariectomized female rats despite CA3 dendritic retraction: possible involvement of CA1 neurons. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1045–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammed AH, Henriksson BG, Soderstrom S, Ebendal T, Olsson T, Seckl JR. Environmental influences on the central nervous system and their implications for the aging rat. Behav Brain Res. 1993;57:183–91. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90134-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammed AH, Zhu SW, Darmopil S, Hjerling-Leffler J, Ernfors P, Winblad B, Diamond MC, Eriksson PS, Bogdanovic N. Environmental enrichment and the brain. Prog Brain Res. 2002;138:109–33. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)38074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moncek F, Duncko R, Johansson BB, Jezova D. Effect of environmental enrichment on stress related systems in rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:423–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura J, Endo Y, Kimura F. A long-term stress exposure impairs maze learning performance in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1999;273:125–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacteau C, Einon D, Sinden J. Early rearing environment and dorsal hippocampal ibotenic acid lesions: long-term influences on spatial learning and alternation in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1989;34:79–96. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(89)80092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park CR, Campbell AM, Diamond DM. Chronic psychosocial stress impairs learning and memory and increases sensitivity to yohimbine in adult rats. Biol Psych. 2001;50:994–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham TM, Winblad B, Granholm AC, Mohammed AH. Environmental influences on brain neurotrophins in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:167–75. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roozendaal B, Phillips RG, Power AE, Brooke SM, Sapolsky RM, McGaugh JL. Memory retrieval impairment induced by hippocampal CA3 lesions is blocked by adrenocortical suppression. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1169–71. doi: 10.1038/nn766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL. Psychobiology of plasticity: effects of training and experience on brain and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 1996;78:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandi C, Loscertales M, Guaza C. Experience-dependent facilitating effect of corticosterone on spatial memory formation in the water maze. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:637–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunanda, Rao MS, Raju TR. Effect of chronic restraint stress on dendritic spines and excrescences of hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons--a quantitative study. Brain Res. 1995;694:312–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uno H, Tarara R, Else JG, Suleman MA, Sapolsky RM. Hippocampal damage associated with prolonged and fatal stress in primates. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1705–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01705.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wainwright PE, Levesque S, Krempulec L, Bulman-Fleming B, McCutcheon D. Effects of environmental enrichment on cortical depth and Morris-maze performance in B6D2F2 mice exposed prenatally to ethanol. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1993;15:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(93)90040-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe Y, Gould E, McEwen BS. Stress induces atrophy of apical dendrites of hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons. Brain Res. 1992;588:341–5. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Will BE, Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL, Hebert M, Morimoto H. Relatively brief environmental enrichment aids recovery of learning capacity and alters brain measures after postweaning brain lesions in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91:33–50. doi: 10.1037/h0077306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winocur G. Environmental influences on cognitive decline in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:589–97. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright RL, Conrad CD. Chronic stress leaves novelty-seeking behavior intact while impairing spatial recognition memory in the Y-maze. Stress. 2005;8:151–154. doi: 10.1080/10253890500156663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright RL, Lightner EN, Harman JS, Meijer OC, Conrad CD. Attenuating corticosterone levels on the day of memory assessment prevents chronic stress-induced impairments in spatial memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:595–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J, Hou C, Ma N, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Xu L, Li L. Enriched environment treatment restores impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity and cognitive deficits induced by prenatal chronic stress. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]