Abstract

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE

Although chemotherapy has been used in most clinical trials for children with high-grade glioma, no drug regimen has so far stood out as particularly beneficial for these patients.

Based on pre-clinical and clinical experience in adults with similar tumors, we report for the first time the results of a Phase I study which used erlotinib during and after radiotherapy in children with high-grade glioma. We characterized the acute and chronic toxicities associated with erlotinib therapy. Within the context of a Phase I study, we also performed extensive pharmacokinetic and molecular studies.

We observed preliminary encouraging outcome in a subgroup of our patients, particularly those with anaplastic astrocytoma. Therefore, the current study established a platform for future clinical trials to incorporate erlotinib in the treatment of high-grade glioma in children.

Purpose

To estimate the maximum-tolerated dose (MTD) of erlotinib administered during and after radiotherapy (RT), and to describe the pharmacokinetics of erlotinib and its metabolite OSI-420 in patients between 3 and 25 years with newly diagnosed high-grade glioma who did not require enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants.

Experimental Design

Five dosage levels (70, 90, 120, 160, and 200mg/m2 per day) were planned in this Phase I study. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were evaluated during first 8 weeks of therapy. Local RT (dose between 54 and 59.4 Gy) and erlotinib started preferentially on the same day. Erlotinib was administered once daily for a maximum of 3 years. Pharmacokinetic studies were obtained after first dose and on day 8 of therapy. Mutational analysis of EGFR kinase domain, PIK3CA, and PTEN was performed in tumor tissue.

Results

Median age at diagnosis of 23 patients was 10.7 years (range, 3.7 to 22.5 years). MTD of erlotinib was 120mg/m2 per day. Skin rash and diarrhea were generally well controlled with supportive care. DLTs were diarrhea (n=1), increase in serum lipase (n=1), and rash with pruritus (n=1). The pharmacokinetic parameters of erlotinib and OSI-420 in children were similar to those described in adults. However, there was no relationship between erlotinib dosage and drug exposure. No EGFR kinase domain mutations were observed. Two patients with glioblastoma harbored mutations in PIK3CA (n=1) or PTEN (n=1).

Conclusions

Although the MTD of erlotinib in children with newly diagnosed high-grade glioma was 120mg/m2 per day, pharmacokinetic studies demonstrated wide inter-patient variability in drug exposure.

Keywords: children, erlotinib, glioma, high-grade, radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Whereas high-grade gliomas, in particular glioblastoma, represent more than 50% of all primary malignant brain tumors in adults, similar neoplasms arising outside the brainstem constitute only 10% of all primary brain tumors in children.1 Like adults, the combination of maximum safe surgery, radiotherapy (RT), and standard chemotherapy has not improved the outcome of children older than 3 years with high-grade glioma (1).

Recently, the combination of RT and temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide showed superior outcome compared to RT only in the treatment of adults with newly diagnosed glioblastoma (2). Several studies have used temozolomide in the treatment of children with high-grade glioma; however, the results so far have been disappointing (3–6).

New biologic agents which inhibit relevant cellular targets have been employed in the treatment of adults with high-grade glioma (7). Although high-grade gliomas in children are biologically distinct from those in adults (8–10), abnormalities in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway are prevalent in both age groups (9, 11, 12). Although EGFR amplification is rare in pediatric high-grade glioma (9, 11, 13, 14), these tumors commonly overexpress EGFR (9, 11).

Erlotinib (Tarceva®, OSI Pharmaceuticals, Melville, NY; Roche, Basel, Switzerland; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), a small-molecule inhibitor of EGFR, is also an antiangiogenic agent. Although EGFR inhibitors, and particularly erlotinib, have shown benefit when combined with RT in preclinical models of glioblastoma (15, 16), to our knowledge these studies have not been performed in xenografts derived from pediatric patients. Several clinical trials demonstrated modest activity of erlotinib in the treatment of adults with recurrent high-grade glioma (17–19).

Therefore, we conducted this study to estimate the maximum-tolerated dose (MTD) and to characterize the pharmacokinetics of erlotinib administered concurrently with and after RT in pediatric patients with newly diagnosed high-grade glioma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients between 3 and 25 years of age with newly diagnosed high-grade glioma were eligible for this study. Additional eligibility criteria consisted of: (i) Interval between surgery and start of therapy ≤ 42 days; (ii) Performance score ≥ 40; (iii) Adequate hematologic (absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1,000/μL, platelet count ≥ 100,000/μL, and hemoglobin concentration ≥ 8g/dL), renal (serum creatinine concentration < 2 times the institutional normal values for age), and hepatic (total bilirubin concentration < 1.5 times the institutional upper limit of normal, SGPT < 5 times the institutional upper limit of normal, and albumin ≥ 2g/dL) function. Exclusion criteria consisted of: (i) Diagnosis of diffuse brainstem glioma; (ii) Diagnosis of secondary high-grade glioma; (iii) Presence of leptomeningeal metastatic disease; (iv) Use of enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants (EIACs); (v) Use of other concomitant anticancer therapy; (vi) Presence of other significant concomitant medical problems; (vii) Pregnant or lactating patients. Female patients of childbearing age and male patients of child-fathering potential had to agree to use safe contraceptive methods. For patients who were weaned off EIACs, at least 7 days were required between discontinuation of EIACs and start of erlotinib. Central histologic review of all cases was conducted by a neuro-pathologist (D.W.E).

Our institutional review board approved this protocol before initial patient enrollment and continuing approval was maintained throughout the study. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from patients or their legal guardians, and assents were obtained when appropriate.

Study Design and Treatment Plan

This single institution study followed a standard Phase I-study design. The dosage of erlotinib was increased by about 30% in each dosage level starting at 80% of the MTD in adults with solid tumors (20). Five dosage levels were planned (70, 90, 120, 160, and 200 mg/m2 per day). A traditional 3+3 dose escalation scheme was used to estimate the MTD. MTD was defined as the highest dosage level in which no more than one of six assessable patients had experienced DLTs. The DLT-evaluation period comprised the first eight weeks of therapy. DLT was defined as any of the following toxicities attributable to erlotinib therapy: thrombocytopenia grade 3 and 4; neutropenia grade 4; or any grade 3 and 4 nonhematologic toxicity except for grade 3 diarrhea and grade 3 nausea and vomiting lasting ≤48 hours in patients not receiving optimal supportive therapy, grade 3 skin rash which did not affect normal daily activities, grade 3 fever or non-neutropenic infection, grade 3 seizures, grade 3 weight gain or loss, and grade 3 transaminase elevation that returned to grade 1 or baseline within 7 days. After enrollment of the first four patients on study, we also excluded as DLT grade 3 and 4 electrolyte abnormalities that resolved to ≤ grade 2 within 7 days. Toxicities were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0.

Erlotinib and local RT started on the same day except for three patients who were weaned off EIACs before the start of erlotinib. In the latter cases, erlotinib therapy was started within 6 days from beginning of RT. Three-dimensional conformal RT was delivered as 1.8-Gy fractions to a total dose of 59.4 Gy. The treatment volume encompassed the tumor bed, the surrounding residual T2-weighted signal abnormality, a 2-cm margin to account for microscopic disease, and a 0.3 to 0.5-cm margin to account for uncertainty in immobilization and patient’s positioning. Whole brain RT was administered at a dose of 54 Gy for patients with > 70% of the brain volume involved by tumor. Erlotinib was administered as 25-, 100-, and 150-mg tablets 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals once daily during and after RT. Maximum planned treatment duration was 3 years. The day 2 dose of erlotinib was held in patients undergoing pharmacokinetic studies. For patients not receiving erlotinib at the MTD, the drug dose could be increased once to the next dosage level if therapy had been well tolerated during first 6 cycles of therapy.

Radiologic evaluation consisting of brain and spine MRI were done within 2 weeks before enrollment on study. Brain MRI was repeated 8 weeks after start of therapy, and every 12 weeks thereafter. Complete and partial responses were defined as complete disappearance and ≥ 50% reduction of tumor as measured by bi-dimensional measurements, respectively. Stable or improved neurologic findings for at least 6 weeks on a stable or decreasing dose of corticosteroids were required in both instances. Progressive disease was defined as worsening neurologic findings attributed to tumor progression, and/or increase of > 25% in bi-dimensional tumor measurements, and/or appearance of tumor in previously uninvolved areas and/or need of increasing doses of corticosteroid to maintain stable neurologic exam. Stable disease consisted of all other situations not defined above.

Pharmacokinetic Studies

Blood samples for optional pharmacokinetic studies were obtained in consenting patients. Two milliliters of blood were collected in heparinized tubes before and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 (±2), 30 (±4), and 48 (±4) hours after first dose of erlotinib, and before and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 (±2) hours after dose on day 8. Once collected, blood samples were centrifuged and the plasma was stored at −80°C until analysis. Pharmacokinetic analysis of erlotinib and its primary metabolite OSI-420 was performed by high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (21). The lower limits of quantification for erlotinib and OSI-420 were 10 ng/ml and 1 ng/ml, respectively. The inter-assay precision during validation was < 7% for both erlotinib and OSI-420 at all concentrations. Pharmacokinetic parameters consisting of maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), area under concentration-time curve during dosing intervals (AUC0→24 and AUC0→48), and time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax) after day 1 and 8 of therapy were calculated using standard noncompartmental methods from the plasma concentration-time profiles of erlotinib and OSI-420.

Molecular and Immunohistochemical Studies

DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue using standard techniques. The entire PTEN coding sequence (exons 1 to 9), exons 1, 9, and 20 of PIK3CA, which contain hotspots for mutations, and exons 17 to 24 of EGFR, which encode its kinase domain, were evaluated using exon-specific polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) amplification with previously described primers (22–24). PCR products were purified from agarose gels using QIAEX II Purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and direct DNA sequencing was performed using Applied Biosystem 3730XL DNA Analyzers. All potential mutations were verified by re-amplification from genomic DNA and direct sequencing of the mutated exon.

Unstained slides were available for immunohistochemistry in 21 cases. Immunohistochemistry was performed for PTEN, phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT) and S6 (p-S6; #9559, 1:100; #9271, 1:50 and #2211, 1:100, respectively; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) (25). Endothelial cells served as an internal positive control for PTEN. Brain tissue sections from Pten conditional knockout or control mice also served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Tumor lesions were considered positive if greater than 25% cells were immunoreactive. Immunoreactivity was graded as strongly positive (++), weakly positive (+), or negative (−).

Statistical Analysis

Progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated according to the method of Kaplan and Meier (26). Standard error estimates were calculated by the method of Peto et al. (27). PFS reflected the interval between diagnosis and clinical and/or radiologic tumor progression, or death. OS was defined as the interval between diagnosis and death. Patients not experiencing an event were censored at their last follow-up date.

RESULTS

Twenty-three patients were enrolled on study between March 2005 and June 2007. The patients’ characteristics before start of therapy are shown in Table 1. Three patients were older than 18 years at diagnosis. We retrospectively found that one patient had undergone placement of carmustine–loaded wafers before start of RT and erlotinib therapy at another institution; this patient was considered assessable for DLT evaluation. One patient harbored an anaplastic astrocytoma which originated in the brainstem and exophytically extended towards the left cerebellopontine angle.

Table 1.

Patients Characteristics at the Start of Therapy

| Characteristics | No. of Patients(n =23) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||

| Median | 10.7 | |

| Range | 3.7–22.5 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 13 | 57 |

| Female | 10 | 43 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Glioblastoma | 12 | 52 |

| Anaplastic Astrocytoma | 8 | 35 |

| Other High-Grade Gliomas¶ | 3 | 13 |

| Location | ||

| Cerebral Hemispheres | 15 | 65 |

| Thalamus | 5 | 22 |

| Cerebellum | 2 | 9 |

| Other § | 1 | 4 |

| Performance Status | ||

| 90–100 | 11 | 48 |

| 70–80 | 5 | 22 |

| 50–60 | 7 | 30 |

| Degree of Resection | ||

| Gross/Near Total | 11 | 48 |

| Subtotal | 6 | 26 |

| Partial/Biopsy | 6 | 26 |

, anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (n =2) and anaplastic ganglioglioma (n =1)

, This patient had an anaplastic astrocytoma originating from the lateral brainstem and extending towards the cerebellopontine angle

Toxicities

Of three patients initially enrolled on the 70mg/m2 dosage level, one patient experienced grade 3 hypokalemia which was easily corrected with oral potassium supplementation. The protocol was then opened for three additional patients at the same dosage level. A second patient enrolled on the 70mg/m2 dosage level also developed easily reversible grade 3 hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia. Following the amendment to exclude as DLTs grade 3 and 4 electrolyte abnormalities that resolved to ≤ grade 2 within 7 days, none of three additional patients enrolled on the 70mg/m2 dosage level experienced DLTs. Likewise, all three patients treated at the 90mg/m2 dosage level tolerated therapy well. Erlotinib dosage was increased to 120mg/m2 and one patient experienced grade 3 diarrhea despite optimal supportive care. None of five other assessable patients treated at this dosage level experienced DLTs. One patient at the 120mg/m2 dosage level was not assessable for toxicity because of early tumor progression. Of three patients enrolled on the 160mg/m2 dosage level, one patient experienced DLT consisting of grade 3 increase in serum lipase concomitant with episodes of abdominal pain but without other findings compatible with pancreatitis. Of three additional patients enrolled at the same dosage level, one patient experienced grade 3 intolerable skin rash and pruritus. Therefore, 120mg/m2 per day was established as the MTD for our patients. Table 2 provides a summary of significant toxicities during the DLT-evaluation period.

Table 2.

Summary of Toxicities During the Dose-Limiting Toxicity-Evaluation Period

| 70mg/m2 (n=7) § | 90mg/m2 (n=3) | 120mg/m2 (n=7) ‡ | 160mg/m2 (n=6) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of Actual Dosage (mg/m2) | 68–83 | 85–87.5 | 107–128 | 151.5–167 | ||||||||||

| Toxicity (Grade) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Lymphopenia | 1 | 3 | 1 ¶ | 2 ¶ | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 ¶ | 1 ¶ | - | - | 3 ¶ | 1 ¶ |

| Rash | 1 | 5 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 1 † | - |

| Diarrhea | 2 | - | - | - | 3 | - | 5 | - | 1 † | - | 4 | - | - | - |

| Nausea | 5 | - | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 1 | - | - | 3 | - | - | - |

| Vomiting | 3 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| Hypokalemia | 1 | - | 2 ¶ | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 ¶ | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| Hypophosphatemia | 2 | 1 | 1 ¶ | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Indirect hyperbilirubinemia | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Mucositis | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Fatigue | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| Anorexia | 2 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Elevation of SGPT | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | - | 3 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| Infection without neutropenia | - | 3 | 1 ¶ | - | 1 | - | 1 | 4 | - | - | 1 | 3 | - | - |

| Increase of serum lipase | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 † | - |

Four patients were treated before and three patients after the study was amended to exclude grade 3 and 4 electrolyte abnormalities that resolved to at least grade 2 within 7 days

One patient was not assessable for toxicity because of early tumor progression

dose-limiting toxicity

These toxicities were not considered dose-limiting toxicities according to the study criteria

Chronic therapy with erlotinib has been well tolerated. Treatment duration in our patients ranged from 6 weeks to 26 months. Eighteen and 12 patients have received treatment for at least 6 and 12 months, respectively. One patient with left thalamic glioblastoma developed a second neoplasm (rhabdomyosarcoma) outside the RT field within 6 months of start of therapy. One patient with a thalamic tumor died of intratumoral hemorrhage at the time of radiologic progression and following ventricular decompression due to hydrocephalus. Although the hemorrhage was definitely related to the surgical procedure, it could be possibly associated with erlotinib therapy. Other chronic toxicities included grade 1/2 indirect hyperbilirubinemia, grade 1–3 hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia, and grade 1–3 lymphopenia.

Pharmacokinetic Studies

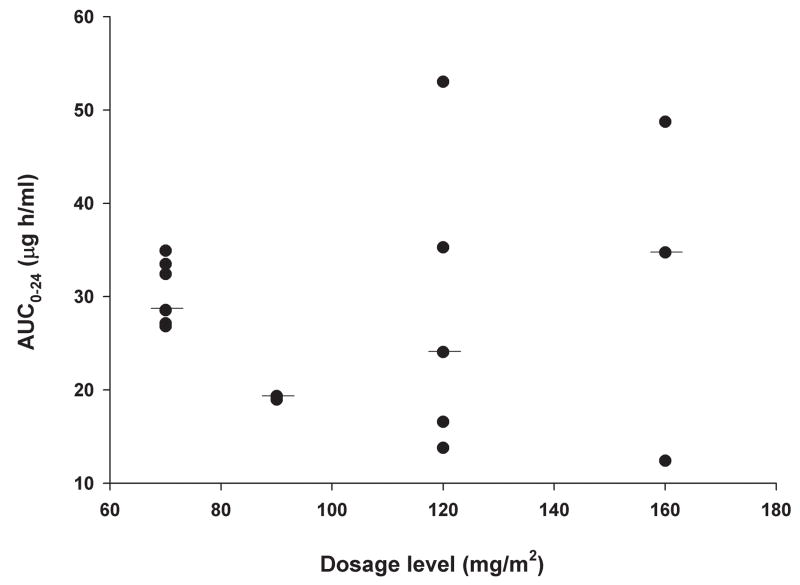

The results of the pharmacokinetic parameters, which were obtained in 17 patients, are summarized in Table 3. Although the calculated dose of erlotinib was rounded to the nearest 25 mg, the actual dosage administered to patients was within 12% of the prescribed dosage in all but one patient. The latter patient received erlotinib at the lowest dosage level and the actual dosage was 19% higher than the calculated dose. The AUC0→48 (after first dose) and AUC0→24 (day 8 of therapy) of erlotinib did not increase with increasing dosage (Figure 1). No correlation was identified between AUC0→48 of erlotinib and OSI-420 normalized to dosage and patient age at diagnosis.

Table 3.

Summary of Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Erlotinib and OSI-420

| AFTER FIRST DOSE | DAY 8 OF THERAPY | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erlotinib | OSI-420 | Erlotinib | OSI-420 | |||||||

| Dosage Level (mg/m2) | Cmax(mg/ml) | Tmax (h) | AUC0→∞ (mg·h/ml) | Cmax (mg/ml) | AUC0→∞ (mg·h/ml) | Cmax (mg/ml) | Tmax (h) | AUC0→∞ (mg·h/ml) | Cmax (mg/ml) | AUC0→∞ (mg·h/ml) |

| 70 (n =7) | 1.3 (0.94–2.2) | 4 (2.1–8.2) | 34.9 (23.1–52.6) | 0.13 (0.05–0.2) | 2.1 (1.2–3.3) | 1.8 (1.7–2.8) | 2.1 (1–4.1) | 28.8 (21.8–30.9) | 0.25 (0.2–0.6) | 3.3 (2–6.9) |

| 90 (n =2) | 1.6 (1.3–1.8) | 3.1 (2–4.1) | 23.9 (14.4–33.3) | 0.16 (0.12–0.2) | 1.9 (1.4–2.3) | 1.3 | 2.6 (1.2–4) | 21.2 (18.1–24.2) | 0.17 | 2.1 (1.7–2.4) |

| 120 (n =5) | 1.2 (0.5–2) | 2.2 (1–4) | 27.8 (18.9–28.8) | 0.14 (0.1–0.3) | 2.5 (1.7–2.7) | 1.4 (1–3) | 1.75 (1.3–4) | 23.1 (11.8–51.2) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 2.8 (1.9–5.9) |

| 160 (n =3) | 1.8 (1.3–3) | 2.2 (2–2.5) | 37.1 (33.1–50.6) | 0.32 (0.26–0.33) | 4.2 (4.1–5.2) | 2 (1.3–2.4) | 2.2 (1–4) | 35.5 (23.7–51) | 4.3 (3.8–6.1) | |

Note: Values are provided as median with range in parenthesis

Abbreviations: Cmax, maximal concentration; Tmax, time for maximal concentration; AUC0→∞, area under concentration-time curve from zero to infinity

Figure 1.

Erlotinib exposure after first dose (area under concentration-time curve from 0 to 48 hours; Figure 1A) and on day 8 of therapy (area under concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 hours; Figure 1B)

Molecular and Immunohistochemical Studies

One PTEN (R130*) and one PIK3CA (H1047R) mutation were identified in patients with glioblastoma. No EGFR kinase domain mutations were identified.

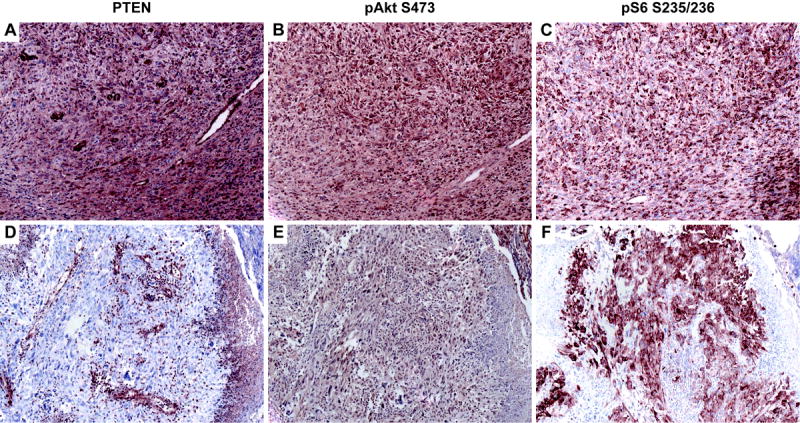

Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the tumor containing a PIK3CA mutation expressed normal levels of PTEN, while the tumor containing a truncating PTEN mutation showed loss of PTEN protein in tumor cells, while normal and reactive cells expressed PTEN (Figure 2). Both tumors showed elevated levels of p-AKT and p-S6, indicating activation of downstream effectors in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway (Figure 2). However, elevated levels of p-AKT (19 of 19) and p-S6 (15 of 20) were also detected in tumors lacking mutations in PIK3CA or PTEN.

Figure 2.

Representative PTEN, phosphorylated AKT and S6 immunostaining of high grade gliomas. The tumor containing a PIK3CA mutation (A–C) expressed high levels of PTEN (A), and showed evidence of PI3K pathway activation by strong immunoreactivity for both phosphorylated AKT (B) and S6 (C). The tumor cells harboring PTEN mutation (D–F) showed loss of PTEN expression in tumor cells, with normal expression in surrounding normal cells (D). Consistent with an absence of functional PTEN, tumor cells were positive for phosphorylated AKT (E) and S6 (F).

Outcome

No objective radiologic responses to therapy were observed. Disease stabilization was documented in 16 patients. Four patients have remained without evidence of disease after undergoing gross tumor resection at a median of 2.15 years (range, 1.5 to 2.2 years). Sixteen patients have already experienced tumor progression (Table 4).

Table 4.

Details About Treatment and Outcome for all Patients

| Patient Number | Dosage Level(mg/m2) | Age at Diagnosis/Gender | Histologic Diagnosis | Tumor Location | Surgical Resection | PFS (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | 7.5/M | Anaplastic Astrocytoma | Cerebellum | Biopsy | 0.7 |

| 2 | 70 | 10/M | Glioblastoma | Multifocal | PR | 2.2 |

| 3 | 70 | 8.2/F | Glioblastoma | Thalamus | STR | 0.5 |

| 4 | 70 | 6.3/F | Glioblastoma | Thalamus | NTR | 0.7 |

| 5 | 70 | 9.9/F | Glioblastoma | Gliomatosis Cerebri | PR | 0.9 |

| 6 | 70 | 10.4/F | Anaplastic Astrocytoma | Gliomatosis Cerebri | Biopsy | 1.9 |

| 7 | 70 | 14/M | Glioblastoma | Temporal Lobe | NTR | 1.3 |

| 8 | 90 | 22.5/M | Anaplastic Oligoastrocytoma | Temporal Lobe | GTR | 1.9 |

| 9 | 90 | 11.8/M | Anaplastic Ganglioglioma | Frontal Lobe | GTR | 2.2 + |

| 10 | 90 | 18.1/F | Anaplastic Astrocytoma | Temporal Lobe | GTR | 2.2 + |

| 11 | 120 | 13.1/M | Glioblastoma | Temporal Lobe | GTR | 2.1 + |

| 12 | 120 | 14.4/F | Glioblastoma | Frontal Lobe | NTR | 0.6 |

| 13 | 120 | 3.7/F | Glioblastoma | Frontal Lobe | NTR | 0.2 |

| 14 | 120 | 7.2/M | Glioblastoma | Bi-thalamic | Biopsy | 0.4 |

| 15 | 120 | 13.7/M | Glioblastoma | Frontal Lobe | STR | 0.4 |

| 16 | 120 | 6.2/M | Anaplastic Oligoastrocytoma | Parietal Lobe | GTR | 1.5 + |

| 17 | 120 | 19/M | Anaplastic Astrocytoma | Frontal Lobe | STR | 1.5 + |

| 18 | 160 | 13.2/F | Anaplastic Astrocytoma | Brainstem | NTR | 1.3 + |

| 19 | 160 | 14.8/M | Glioblastoma | Frontal Lobe | NTR | 0.6 |

| 20 | 160 | 10.7/F | Glioblastoma | Thalamus | STR | 0.2 |

| 21 | 160 | 8/F | Anaplastic Astrocytoma ‡ | Thalamus | Biopsy | 1.2 |

| 22 | 160 | 14.3/M | Anaplastic Astrocytoma | Frontal Lobe | STR | 1 + |

| 23 | 160 | 7.4/M | Anaplastic Astrocytoma ‡ | Cerebellum | STR | 0.9 |

Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial resection; STR, subtotal resection; NTR, near-total resection; GTR, gross total resection

Histologic diagnosis was changed to glioblastoma at second operation

The 1-year PFS and OS for all patients were 56% ± 10% and 78% ± 9%, respectively. The 2-year PFS and OS for all patients were 35% ± 12% and 48% ± 12%, respectively. The 1-year PFS and OS for patients with glioblastoma were 33% ± 12% and 67% ± 13%, respectively. The 1-year PFS and OS for patients with anaplastic astrocytoma were 75% ± 14% and 86% ± 12%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that erlotinib administered during and after RT at a dosage of 120mg/m2 per day is well tolerated by pediatric patients with newly diagnosed high-grade glioma. The MTD reached in the current study is higher than the established MTD of erlotinib for children (28) and adults with recurrent solid tumors, (20) and equivalent to the MTD established for adults with recurrent high-grade glioma who did not receive EIACs (17). Smoking or use of EIACs influence the pharmacokinetics of erlotinib by increasing its metabolism, and hence the tolerance to therapy (17, 29). None of our patients smoked or required EIACs during therapy. Unlike previous studies, we arbitrarily mandated a shorter interval of 7 days between discontinuation of EIACs and start of erlotinib. Of 9 patients who were weaned off EIACs before start of therapy; five discontinued EIACs less than 10 days before start of erlotinib. However, the DLT-evaluation period of 8 weeks in the current study was much longer than previous studies (17, 20, 28). Therefore, we considered negligible the impact of previous use of EIACs on the evaluation of toxicities in the current study. We can not elaborate on the influence of corticosteroids on the exposure to erlotinib since only one of five patients who received dexamethasone during initial pharmacokinetic studies went on to have repeat evaluation 2 weeks after discontinuation of corticosteroids; the clearance of erlotinib remained stable in this patient.

The side effects of erlotinib observed in our patients were very similar to those reported in adults (17, 20). Hypokalemia during erlotinib therapy had been previously described; (30) however, hypophosphatemia had only been reported when erlotinib therapy was combined with other medications (31). The mechanism of electrolyte abnormalities associated with erlotinib therapy is not clear. Like other pediatric Phase I studies, we excluded electrolyte abnormalities as DLTs based on the lack of clinical significance of these toxicities and with the hope of reaching higher drug concentrations of erlotinib in the central nervous system with the use of higher dosage levels (21). We also removed tolerable grade III skin rash as a DLT because of the reported better outcome of patients with other cancers who experienced this toxicity during erlotinib therapy (32).

We were also able to assess the long-term side effects of erlotinib therapy in children since more than three-fourths of our patients have received therapy for at least 6 months. No significant long-term toxicities possibly associated with erlotinib therapy have been observed except for a second neoplasm and a fatal episode of intratumoral hemorrhage in the context of tumor progression. The short interval from start of therapy and the diagnosis of second neoplasm and its occurrence outside the RT fields suggest a reason unrelated to therapy; however, no evidence in history, physical exam, or molecular analysis of tumor samples supported a predisposition to develop a second cancer in this patient.

The results of our pharmacokinetic studies obtained at steady-state, the inter-patient variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters of erlotinib, and the ratio of erlotinib to OSI-420 exposure were similar to previously published data in adults (17, 20). In the study of Prados et al., patients not requiring EIACs who received erlotinib at a dose of 200mg per day had mean Cmax, Tmax, and AUC0→24 of 1.44 μg/ml, 1.8 h, and 21.2 μg·h/ml, respectively (17). We reported very similar results in patients who received erlotinib at 120mg/m2 per day, which is equivalent to an adult dose slightly above 200mg. In the current study, no association was observed between the dosage of erlotinib and exposure. Likewise, Prados et al. did not observe a relationship between the dose of erlotinib and exposure in patients treated with erlotinib alone (17).

Several studies have evaluated the relationship between molecular characteristics of high-grade glioma in adults and response to treatment with small-molecule EGFR inhibitors (33–38). Haas-Kogan et al. showed that patients with glioblastoma whose tumors expressed high levels of EGFR and low levels of p-AKT responded better to erlotinib therapy (34). In another study, co-expression of EGFRvIII and PTEN was associated with better response of patients with high-grade glioma to EGFR inhibitors (36). Unlike non-small cell lung cancer, (22, 39) EGFR kinase domain mutations are rarely found in high-grade gliomas in adults (33–38). Likewise, EGFR kinase domain mutations were not observed in our patients. Since the activity level of the PI3K/AKT pathway seems to influence the tumor response to EGFR inhibitors, (34) we performed an exploratory evaluation of two key regulatory genes (PIK3CA and PTEN) and three immunohistochemical markers (PTEN, p-AKT and p-S6) of this pathway. Similar to previous studies, (9, 13, 40, 41) we demonstrated mutations in either one of these genes in a subset of our patients with glioblastoma. Immunohistochemistry showed strong expression of p-AKT and p-S6 in the tumors bearing mutation in PIK3CA or PTEN, consistent with activation of the PI3K pathway. However, similar evidence of PI3K pathway activation was observed in the majority of tumors lacking detectable mutations in PIK3CA or PTEN, suggesting that the pathway is engaged by alternative mechanisms in this cohort of pediatric high-grade glioma. Despite our detailed molecular and immunohistochemical analysis in the context of a Phase I study, no correlation was found between markers of PI3K/AKT pathway activation and response to the current therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support [CORE] Grant P30 CA21765; Musicians Against Childhood Cancer (MACC); the Noyes Brain Tumor Foundation; Ryan McGhee Foundation; OSI Pharmaceuticals Inc.; Genentech Inc.; and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

This work was partially supported by Genentech Inc. and by OSI Pharmaceuticals Inc.; the first author received remuneration as a consultant for OSI Pharmaceuticals Inc.

We thank Annemarie McCllelan for her support in conducting this study.

Footnotes

The results of this manuscript were presented at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, June 1–5, 2007, and the 13th International Symposium on Pediatric Neuro-Oncology, Chicago, June 29–July 2, 2008

Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States: 2004–2005 Statistical Report: Primary Brain Tumors in the United States Statistical Report, 1998–2002. http://www.cbtrus.org/reports//2005-2006/2006report.pdf

References

- 1.Broniscer A, Gajjar A. Supratentorial high-grade astrocytoma and diffuse brainstem glioma: two challenges for the pediatric oncologist. Oncologist. 2004;9:197–206. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-2-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, Van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lashford LS, Thiesse P, Jouvet A, et al. Temozolomide in malignant gliomas of childhood: a United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group and French Society for Pediatric Oncology Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4684–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broniscer A, Chintagumpala M, Fouladi M, et al. Temozolomide after radiotherapy for newly diagnosed high-grade glioma and unfavorable low-grade glioma in children. J Neurooncol. 2006;76:313–9. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-7409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruggiero A, Cefalo G, Garré ML, et al. Phase II trial of temozolomide in children with recurrent high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2006;77:89–94. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson HS, Kretschmar CS, Krailo M, et al. Phase 2 study of temozolomide in children and adolescents with recurrent central nervous system tumors: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2007;110:1542–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omuro AM, Faivre S, Raymond E. Lessons learned in the development of targeted therapy for malignant gliomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1909–19. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rickert CH, Sträter R, Kaatsch P, et al. Pediatric high-grade astrocytomas show chromosomal imbalances distinct from adult cases. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1525–32. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, James CD, et al. Rarity of PTEN deletions and EGFR amplification in malignant gliomas of childhood: results from the Children’s Cancer Group 945 cohort. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:418–24. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faury D, Nantel A, Dunn SE, et al. Molecular profiling identifies prognostic subgroups of pediatric glioblastoma and shows increased YB-1 expression in tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1196–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bredel M, Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression and gene amplification in high-grade non-brainstem gliomas of childhood. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1786–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher EA, Furnari FB, Bachoo RM, et al. Malignant glioma: genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1311–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.891601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raffel C, Frederick L, O’Fallon JR, et al. Analysis of oncogene and tumor suppressor gene alterations in pediatric malignant astrocytomas reveals reduced survival for patients with PTEN mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4085–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korshunov A, Sycheva R, Gorelyshev S, et al. Clinical utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in nonbrainstem glioblastomas of childhood. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1258–63. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chakravarti A, Chakladar A, Delaney MA, et al. The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway mediates resistance to sequential administration of radiation and chemotherapy in primary human glioblastoma cells in a RAS-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4307–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkaria JN, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, et al. Use of an orthotopic xenograft model for assessing the effect of epidermal growth factor receptor amplification on glioblastoma radiation response. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2264–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prados MD, Lamborn KR, Chang S, et al. Phase 1 study of erlotinib HCl alone and combined with temozolomide in patients with stable or recurrent malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2006;8:67–78. doi: 10.1215/S1522851705000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cloughesy TF, Yung WA, Vrendenberg K, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib in recurrent GBM: molecular predictors of outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:115s. suppl; abstr 1507. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogelbaum MA, Peereboom DM, Stevens G, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib single agent therapy in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Eur J Cancer. 2005;3:135. suppl; abstr 486. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidalgo M, Siu LL, Nemunaitis J, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of OSI-774, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3267–79. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broniscer A, Panetta JC, O’Shaughnessy M, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of erlotinib and its active metabolite OSI-420. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1511–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tashiro H, Blazes MS, Wu R, et al. Mutations in PTEN are frequent in endometrial carcinoma but rare in other common gynecological malignancies. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3935–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser MM, Zhu X, Kwon CH, Uhlmann EJ, Gutmann DH, Baker SJ. Pten loss causes hypertrophy and increased proliferation of astrocytes in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7773–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34:585–612. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakacki RI, Tersak J, Blaney S, et al. A pediatric phase I trial and pharmacokinetic (PK) study of erlotinib (ERL) followed by the combination of ERL with temozolomide (TMZ): a Children’s Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:18s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2306. (suppl; abstract 9015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamilton M, Wolf JL, Rusk J, et al. Effects of smoking on the pharmacokinetics of erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2166–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Lindeman NI, et al. Phase II clinical trial of chemotherapy-naive patients > or = 70 years of age treated with erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:760–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duran I, Hotté SJ, Hirte H, et al. Phase I targeted combination trial of sorafenib and erlotinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4849–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Soler R. Phase II clinical trial data with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib (OSI-774) in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2004;6:S20–3. doi: 10.3816/clc.2004.s.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rich JN, Rasheed BK, Yan H. EGFR mutations and sensitivity to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1260–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haas-Kogan DA, Prados MD, Tihan T, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor, protein kinase B/Akt, and glioma response to erlotinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:880–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lassman AB, Rossi MR, Razier JR, et al. Molecular study of malignant gliomas treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: tissue analysis from North American Brain Tumor Consortium Trials 01–03 and 00–01. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7841–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I, et al. Molecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2012–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marie Y, Carpentier AF, Omuro AM, et al. EGFR tyrosine kinase domain mutations in human gliomas. Neurology. 2005;64:1444–5. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158654.07080.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JC, Vivanco I, Beroukhim R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation in glioblastoma through novel missense mutations in the extracellular domain. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallia GL, Rand V, Siu IM, et al. PIK3CA gene mutations in pediatric and adult glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:709–14. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartmann C, Bartels G, Gehlhaar C, Holtkamp N, von Deimling A. PIK3CA mutations in glioblastoma multiforme. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2005;109:639–42. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]