Abstract

Objective:

We explored the relationships between two domains of alcohol-related cognitions (expectations and reasons for drinking) and their associations with alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence. It is hypothesized that alcohol-related cognitions will relate directly to drinking behaviors and indirectly to alcohol dependence.

Method:

Data came from the 1995 National Alcohol Survey, which included black and Hispanic oversamples. The analysis was restricted to 2,817 respondents who reported alcohol consumption at least once in the past year. Path analysis, including key demographic factors, modeled the associations between expectations, reasons for drinking, frequency of heavy drinking, and alcohol dependence.

Results:

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses yielded separate latent variables for expectations (positive and negative), reasons for drinking (social and escape), frequency of heavy alcohol use, and alcohol-dependence symptoms. Associations between positive expectations and frequency of heavy drinking were partially mediated by social and escape reasons for drinking. Associations between negative expectancies and alcohol dependence were partially mediated by escape reasons for drinking. Associations between reasons for drinking and alcohol dependence were partially mediated by the frequency of heavy drinking. Associations between demographic variables and alcohol dependence were mediated by the frequency of heavy drinking; black race and Hispanic ethnicity also showed additional direct effects on dependence.

Conclusions:

Alcohol-related cognitions exhibit complex associations with drinking behaviors and alcohol dependence. Implications for research on ethnic minority health disparities and public policy are discussed.

Studies of alcohol-related cognitions (e.g., attitudes, beliefs, expectancies) have long been studied (Cahalan et al., 1969; Knupfer et al., 1963; Straus and Bacon, 1953). One consistent finding from general population surveys indicates that the most frequent reason related to alcohol consumption reported by respondents is to celebrate (i.e., sociability function), whereas a smaller proportion of the population cite drinking to relieve stress as a primary reason. Cahalan et al. (1969) operationalized the distinction between social and “escape drinking.” Knupfer et al. (1963) found that those who said they drank to “escape” or to modify their mood also usually gave sociability reasons for drinking; thus heavier drinkers tended to report more reasons for drinking than lighter drinkers.

Drawing on social learning theories, “escape” drinking has been conceptualized as drinking for emotional regulation (Lang et al., 1999), drinking to cope with distress (Abbey et al., 1993; Cooper et al., 1988; Smith et al., 1993), and tension-reduction drinking motives (Brown et al., 1980; Leigh and Stacy, 1993). Several studies report associations between the tendency to use alcohol to escape, avoid, or otherwise regulate unpleasant emotions and both alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders (Abbey et al., 1993; Carpenter and Hasin, 1999; Martin et al., 1992). Holahan (2001), in a random adult sample in the San Francisco Bay area, found that drinking to cope at baseline was related to heavier alcohol consumption and drinking problems across the 10-year study interval. Cronin (1997) found sociability reasons (i.e., social camaraderie) to be the strongest predictors of drinking rates, whereas escape (i.e., tension reduction) reasons were the strongest predictors of alcohol-related problems.

There is considerable evidence that alcohol expectancies are related to drinking behavior (Brown et al., 1980; Farber et al., 1980; Leigh, 1989a; Leigh and Stacy, 1993; Sher et al., 1996; Southwick et al., 1981). Expectancies have been shown to mediate other risk factors (e.g., parental models) and alcohol-related behavior (Brown et al., 1987; Sher et al., 1996). Although much of the evidence linking alcohol expectancies with drinking behavior places emphasis on positive effects, negative effects are also important predictors of drinking behavior (Leigh, 1989a). Leigh and Stacy (1993), however, found that positive expectancy was a more powerful predictor of drinking when compared with negative expectancy and suggest the reason for this may relate to the immediacy of the effect (i.e., negative effects having longer term consequences).

Although different domains of alcohol-related cognitions share common variance, some elements are more powerful predictors than others. Leigh (1989b) found that expectancies added significantly to the prediction of drinking behavior when general attitudes were included in the model. Cooper et al. (1988) included both alcohol expectancies and drinking as a coping strategy, finding the latter was a more powerful predictor of alcohol use than expectancies. Cronin (1997) also found that reasons for drinking accounted for more variance in alcohol-use measures than did expectancies for alcohol effects.

Studies indicate that alcohol can act as a primary biological reinforcer; that is, its intoxicating, anxiolytic, and other effects may reinforce continued alcohol consumption (Lewis and Lockmuller, 1990). Although alcohol expectancies and other general attitudes have been shown to precede actual drinking behaviors, among drinkers, alcohol's reinforcing effects may result in associated cognitive expectations regarding both general and specific outcomes. These expectancies, in turn, may form the basis for other alcohol-related cognitions (i.e., reasons for drinking).

The present study concerned the relationships between alcohol-related cognitions, heavy drinking, and alcohol dependence among current drinkers in a national sample of adults. Structural equation modeling was used to examine the underlying structure of both cognitive variables and their associations with alcohol dependence, considering mediational relationships in a path analysis. Hilton (1987) has shown that the association between socioeconomic variables (e.g., age, gender, education, and marital status) and alcohol-dependence symptoms is mediated by the frequency of heavy drinking. Although heavy drinking has been found in risk curve analyses to be a strong predictor of alcohol dependence, independent of volume (Caetano et al., 1997), racial/ethnic groups also have been found to show differences in the relationships between drinking and alcohol dependence (Caetano and Raspberry, 2000). Drawing on the literature, we hypothesized that reasons for drinking would mediate expectations and drinking behavior as well as alcohol dependence (Cooper et al., 1988; Cronin, 1997) and that heavy drinking would mediate the relationship between reasons for drinking and alcohol dependence as well as between demographic status and alcohol dependence. The following path model is tested: alcohol expectancies → reasons for drinking → frequency of heavy alcohol use → alcohol-dependence symptoms. Two crucial research questions are (1) what are the relationships among the two major cognitive constructs and the two alcohol-related constructs and (2) are these relationships invariant across demographic variables, especially the two main ethnic minority groups?

Method

Sample

This study uses the 1995 National Alcohol Survey (NAS; N9) because more recent NASs (N10 and N11 in 2000 and 2005, respectively) do not include cognitive measures meeting the study objectives. Face-to-face interviews for the 1995 NAS were conducted for the Alcohol Research Group by the Institute for Survey Research of Temple University using trained interviewers. The surveys used a stratified national household probability sample of adults age 18 years and older within the 48 contiguous states. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Public Health Institute, with informed consent obtained before the interviews. The NAS included large oversamples of black and Hispanic respondents. Analyses here were limited to respondents who reported consuming alcohol at least once a year (n = 2,817), excluding 51 American Indians, Alaskan natives, Asians, Asian Americans, or Pacific Islanders, leaving a total of 2,766 respondents. Response rates were from 76% to 77% (Caetano and Clark, 1998). For further methodological details on the NAS, see Greenfield et al. (2000). Weighting factors taking into account geographic distributions, age, and gender, and adjusting to the census, were developed independently for white, black, and Hispanic respondents. Analyses took into account the clustered sampling design in deriving standard errors.

Measures

Cognitions.

Measures of cognitions were derived from two domains related to reasons for drinking and expectations using ordered categorical variables (see Table 1 for items included).

Table 1.

Factor loadings for alcohol-related cognitions

| Reasons/expectancies | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

| Reasons for drinkinga | ||

| Drinking is a good way to celebrate. | .55 | .01 |

| It is what most of my friends do when we get together. | .61 | .16 |

| I drink to be sociable. | .81 | −.18 |

| I enjoy drinking. | .52 | .17 |

| Drinking helps me forget about my worries and my problems. | −.05 | .94 |

| Drinking gives me more confidence and makes me sure of myself. | .30 | .61 |

| I drink when I feel tense and nervous. | .02 | .81 |

| Alcohol expectancesb | ||

| If you were to drink enough alcohol to feel the effects, what are the chances that: | ||

| You would become more sociable? | .83 | −.10 |

| You would let loose? | .77 | .08 |

| You would forget your problems? | .57 | .17 |

| You would become less alert? | −.01 | .74 |

| You would feel high or drunk? | .11 | .75 |

| You would feel sick? | −.10 | .66 |

Notes: Items for reasons for drinking were measured in ordinal scales (3 = very important, 2 = somewhat important, 1 = not important, 0 = not a reason). Items for expectations were measured in ordinal scale (4 = very strong chance, 3 = strong chance, 2 = some chance, 1 = not much chance, 0 = no chance).

χ 2 = 15.9, 7 df, root mean square residual (RMSR) < .02;

χ 2 = 6.7, 4 df, RMSR <.01.

Heavy drinking.

Drinking measures included three items: the frequency of drinking five or more drinks of any alcoholic beverage in a day, frequency of drinking “enough to feel the effects,” and similarly “enough to feel drunk.” All items were measured in ordinal scales (see Table 3). Because respondents may differ regarding the effects of alcohol at similar intake levels (see Kerr et al., 2006; Midanik, 1999, 2003) and intoxication may relate to other factors besides intake, such as rate of drinking and body water (Graham et al., 1998), Knupfer (1984) has argued that measures of alcohol effects like these may be more useful predictors of alcohol problems than measures of the number of drinks (see also Greenfield, 1998; Greenfield and Kerr, 2008).

Table 3.

Standardized path coefficients for the modela

| Variable | Expectation |

Reasons |

Heavy drinking | Alcohol dependence | ||

| Positive | Negative | Social | Escape | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | .11* | −.05 | .10 | .06 | .32† | .07 |

| Age, in years | ||||||

| 18-34 | .10 | −.01 | .01 | .11 | .08 | −.06 |

| 35-54 (ref.) | ||||||

| ≥55 | −.46† | −.35† | .01 | −.03 | −.57† | .24 |

| Education | ||||||

| <12 years | −.07 | −.22† | −.02 | .34† | .03 | .15 |

| 12 years (ref.) | ||||||

| >12 years | −.01 | −.05 | .05 | −.14 | −.16† | −.09 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | .03 | −.04 | −.04 | −.17* | −.10* | .01 |

| Previously (ref.) | ||||||

| Never | .19* | −.08 | .05 | .02 | −.01 | .04 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White (ref.) | ||||||

| Hispanic | −.22† | −.06 | −.3.2† | −.03 | .26† | .20* |

| Black | −.08 | −.08 | −.09 | .01 | −.21† | .46† |

| Expectations | ||||||

| Positive | .42† | .41† | .12† | .01 | ||

| Negative | .04 | .17† | −.04 | .16† | ||

| Reasons | ||||||

| Social | .52† | −.20* | ||||

| Escape | .31† | .38† | ||||

| Heavy drinking | .65† | |||||

Notes: Items for heavy drinking were measured in ordinal scale (0 = never in the past year, 1 = once in the past year, 2 = twice in the past year, 3 = 3–6 times, 4 = 7–11 times, 5 = 1–3 times a month, 6 = 1–2 times a week, 7 = 3–4 times a week, 8 = every day or nearly every day). Ref. = referent.

χ 2 = 164.7, 42 df, p < .000; comparative fit index = .97; root mean square error of approximation = .03.

p <. 05;

p < .01.

Alcohol dependence.

A measure of alcohol dependence in the past year was based on 15 dichotomous symptoms related to the seven defining domains in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), criteria for alcohol dependence (Caetano and Tam, 1995; Caetano et al., 1998).

Demographic status.

Demographic variables included gender, age, marital status, years of education, and race/ ethnicity. Gender was defined as 1 = male, 0 = female. Two dummy variables were constructed for age for 18–34 years and 55 years and older, with 35–54 years as the referent group. Marital status was measured by two dichotomous variables indicating married/living with someone and never married, with previously married as the referent. Two dummy variables indicated education: less than high school and some college, with 12 years of education as the referent. Race/ethnicity involved two dichotomous variables comparing non-black Hispanic and non-Hispanic black, with non-Hispanic white respondents as the referent.

Statistical analysis

Structural equation modeling was used to investigate the relationships among demographic characteristics, cognitive measures, alcohol use, and dependence symptoms. As a preliminary step, the cognitive measures, alcohol-use variables, and alcohol-dependence symptom items were analyzed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using a split-half sample approach (EFA in a random half of the sample and a subsequent CFA on the remaining half). Factor analysis results were used to specify the factor structures in separate multiple-indicator and multiple-cause (MIMIC) models. The MIMIC model is a special case of structural equation modeling in which one or more latent variables intervene between a set of observed background variables predicting a set of observed response variables (e.g., Muthén, 1979, 1989; Muthén et al., 1993). Three sets of relationships were evaluated for each latent variable: the relationships between constituent items of the latent variable and the latent variable (the measurement model), the relationships among the latent variable and other covariates (the structural regression equations), and the relationships between the items measuring the latent variable and other observed covariates (the direct effects). The presence of direct effects in the latent variable model implies that, given the same factor mean, there are differences in the probabilities of reporting an item based on the covariates (i.e., the latent variable model may differ by population subgroup).

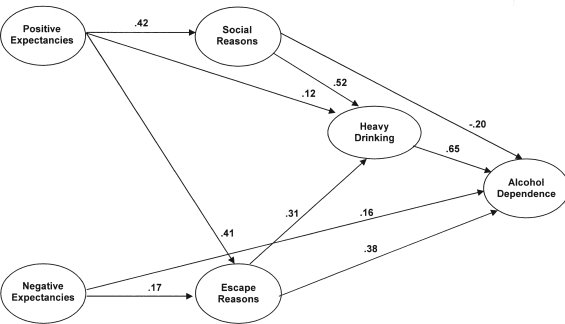

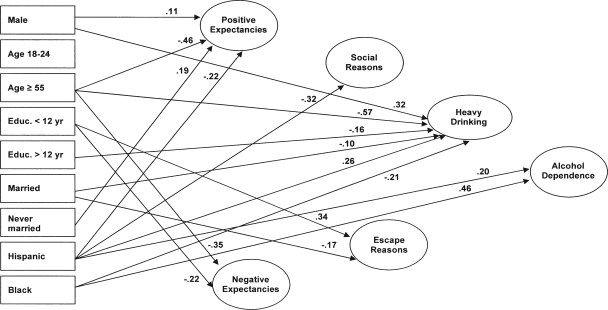

The literature-based hypothesized path model is shown in Figures 1a and 1b for legibility. Following structural equation modeling conventions, circles represent latent factors and rectangles represent observed variables. Analyses were conducting using the Mplus program (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2007, 2005) with the weighted least-squares estimator. Fit indices for measurement models included chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error approximation (RMSEA). Muthén and Muthén (2005) suggest the following cutoff values as indicators of good fit: CFI > .95; RMSEA < .06. For EFA, root mean square residuals (RMSR) should be less than .05. Sampling weights and adjustments for design effects of the 1995 NAS were used in the structural equation modeling, both being accounted for in parameter estimation as well as standard error and model fit calculations.

Figure 1A.

Path model of expectancies and reasons as predictors of heavy drinking and in turn alcohol dependence (standardized path coefficients between latent variables)

Figure 1B.

Same model as Figure 1a but showing standardized path coefficients between demographics and latent variables. Educ. = education; yr. = year.

Results

Approximately 56% of the current drinker sample was male, with other demographics distributed as follows: age 18–34, 44%; 35–54, 40%; 55 and older, 16%; less than 12 years of education, 22%; 12 years of education, 38%; 12 or more years of education, 40%; married, 61%; previously married, 18%; never married, 21%; white, 39%; Hispanic, nonblack, 31%; black, non-Hispanic, 30%.

Measurement model

Reasons for drinking.

The factor loadings of the EFA of the reasons for drinking items are presented in Table 1. Three items—nothing else to do, part of good diet, and like feeling high—had low and similar loadings on both factors and were excluded from further models. The presence of two eigenvalues greater than 1.0 suggested a two-factor model. The two-factor solution (χ2 = 15.9, 7 df; RMSR = .02) improved the fit over the one-factor solution (χ2 = 324.2, 11 df; RMSR = .10), although the two factors are moderately correlated (r = .57). The CFA yielded a good fit (χ2 = 57.7, 9 df; CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05). As shown in Table 1, Factor 1 (social reasons) was well measured by items “to celebrate,” “what friends do,” “to be sociable,” and “enjoy drinking.” Factor 2 (escape/mood self-efficacy reasons) was well measured by the items “forget worries,” “more confident,” and “feel tense.”

Expectancy.

The factor loadings of the EFA of the expectancy items are also given in Table 1. Two items—chances that you would feel more relaxed or become aggressive—had low and similar loadings on both factors and were subsequently excluded. The presence of two eigenvalues greater than 1.0 suggested a two-factor model. The two-factor solution (χ2 = 6.7, 4 df; RMSR = .01) improved the fit over the one-factor solution (χ2 = 663.9, 6 df; RMSR = .14), although the two factors are moderately correlated (r = .43). The CFA yielded a good fit (χ2 = 35.1, 4 df; CFI = .98, RMSEA = .07). As shown in Table 1, Factor 1 (positive expectations) was well measured by items to “become more sociable,” “let loose,” and “forget your problems.” Factor 2 (negative expectations) was well measured by the items “less alert,” “feel high or drunk,” and “feel sick.”

Alcohol dependence.

The factor loading and proportions of the 15 dependence symptoms are shown in Table 2. The single eigenvalue greater than 1 yielded an adequate one-factor solution (χ2 = 88.8, 42 df; RMSR = .06). The CFA yielded an adequate fit (χ2 = 34.7, 16 df; CFI = .98, RMSEA = .02).

Table 2.

Weighted item proportions (%) and factor loadings for alcohol-dependence symptomsa

| Item | % | Loading |

| My hands shook a lot in the morning after drinking. | 3.1 | .79 |

| I needed more alcohol than I used to, to get the same effect as before. | 3.8 | .81 |

| Sometimes I have awakened during the night or early morning sweating all over because of drinking. | 2.4 | .78 |

| Once I started drinking it was difficult for me to stop before I became completely intoxicated. | 4.4 | .81 |

| I sometimes kept on drinking after I had promised myself not to. | 8.6 | .90 |

| I deliberately tried to cut down or quit drinking, but I was unable to do so. | 5.8 | .91 |

| I started drinking even though I hadn't intended to. | 12.9 | .82 |

| I wanted to cut down or quit drinking. | 11.9 | .91 |

| I found that the same amount of drinking had much less effect than it used to. | 7.1 | .82 |

| I have give up or reduced important work or social activities for my drinking. | 1.7 | .91 |

| I have given up or neglected pleasures or interests in favor of drinking. | 2.4 | .92 |

| I spend a lot of my time on drinking or getting over the effects of drinking or doing things to get alcohol. | 1.6 | .97 |

| I kept on drinking although I knew I had a health problem caused by or made worse by my drinking. | 3.6 | .90 |

| I kept on drinking although I felt that my drinking was giving me psychological or emotional problems. | 3.4 | .94 |

| I saw, felt, or heard things that weren't really there when the effects of drinking were wearing off. | 1.7 | .78 |

χ 2 = 88.8, 42 df, root mean square residual = .06.

Frequency of heavy drinking/drunkenness.

The three drinking variables were highly correlated and served as indicators for the latent variable “heavy drinking/drunkenness.” With three categorical variables there are no degrees of freedom to assess the fit of the model (the model is just identified).

MIMIC model direct effects

The presence of direct effects for each latent variable indicates that not all of the effects of background variables are fully mediated by the latent variables, providing evidence of measurement noninvariance. The presence of direct effects in the MIMIC model implies that certain respondents (e.g., men) with the same value on a latent variable (e.g., negative expectation) have higher (or lower) probabilities of reporting a given criterion (e.g., item “feel sick”). There were several latent variable direct effects related to gender and race/ethnicity. Interpretations of direct effects should be viewed in conjunction with the structural estimates of the factors. Because of space limitations, these direct effect estimates will only be summarized. There was a negative direct effect of male gender for the negative expectation item “feel sick” (-.74). Thus, for those with the same value on the latent variable for negative expectation, men have a lower probability of reporting this item relative to women. There were positive effects for male gender related to the latent variable “social reasons for drinking.” For respondents with the same value on this latent variable, men compared with women had a higher probability of reporting “It is what most of my friends do” (.35) and “I enjoy drinking” (.29). Factors values being the same, men compared with women had a higher probability of reporting “frequency of heavy drinking occasions” (.53).

Given the same factor values for “social reasons,” His-panics had a higher probability of reporting “It is what most of my friends do” (.43) and, for “negative expectations,” a lower probability of reporting “become less alert” (-.36) than white respondents. For the latent variable “heavy drinking,” Hispanics had a lower probability of reporting “feeling the effects” (-.41) and “feeling drunk” (-.60). For the latent variable “alcohol dependence,” Hispanics had a lower probability of reporting “hands shake after drinking” (-.67), “need more alcohol for same effect” (-.80), and “difficult to stop drinking before becoming intoxicated” (-.50).

Given the same factor values for “negative expectations,” blacks had a higher probability of reporting “feel sick” (.22) and a lower probability of reporting “become less alert” (-.48) than white respondents. For the latent variable “frequency of heavy drinking,” blacks had a higher probability of reporting “getting high” (.59) and “getting drunk” (.64). For the latent variable “alcohol dependence,” blacks had a lower probability of reporting “need more alcohol for same effect” (-.65) and “difficult to stop drinking before becoming intoxicated” (-.88).

Several direct effects among indicators for each latent variable were included in the model as adjustments for coefficients, but these were of less conceptual relevance for the present study and so are not reported.

Structural equation path model

Path coefficients are summarized in Table 3, and significant standardized path coefficients are shown in Figures 1a and 1b. Because of the large number of significant coefficients, those associated with latent variables are presented in Figure 1a, and those associated with demographic factors are presented in Figure 1b. The inclusion of direct effects related to the latent variables in the MIMIC model improved model fit (χ 2 = 164.7, 42 df; CFI = .97, RMSEA = .03) when compared with the model without direct effects. The inclusion of these direct effects in the path model served to adjust the coefficients shown in Table 3, but the overall results of the two models were comparable. For ease of presentation, these direct effects are not included in Table 3.

Path coefficients in Table 3 indicate that men and those never married reported positive expectations, whereas older respondents and Hispanics (compared with white non-Hispanics) were less likely to report positive expectations. Older respondents and those with less than 12 years of education were less likely to report negative expectations.

Respondents with positive expectations were more likely to report social reasons for drinking. Additionally, Hispanics compared with white non-Hispanics were less likely to report social reasons for drinking. Respondents with either positive or negative expectations were more likely to report escape reasons for drinking, as were those with less than 12 years of education. Married respondents were less likely to report escape reasons for drinking.

Respondents who report social and escape reasons for drinking and positive expectations were more likely to report higher frequencies of heavy drinking. Men and Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites were more likely to report higher frequencies of heavy drinking. Older respondents, those with more than 12 years of education, those who were married, and blacks compared with non-Hispanic whites were less likely to report higher frequencies of heavy drinking.

Respondents who reported frequent heavy drinking were more likely to report alcohol-dependence symptoms. Respondents who reported escape reasons for drinking and those with negative expectancies were more likely to report alcohol-dependence symptoms, whereas those who reported social reasons for drinking were less likely to report these symptoms. Among demographic factors, black and Hispanic compared with non-Hispanic white respondents were more likely to report alcohol-dependence symptoms.

Discussion

The conceptual paradigm we used postulated that alcohol-related cognitions (i.e., reasons for drinking and alcohol expectancies) would be associated with drinking behaviors, which in turn would be associated with alcohol dependence. As shown in Figure 1a, higher positive alcohol expectancies are directly related to both social (.42) and escape (.41) reasons for drinking. Higher negative alcohol expectancies are related to escape (.17) but not social reasons for drinking. Both social (.52) and escape (.31) reasons for drinking are positively related to the frequency of heavy drinking. As indicated in Figure 1a, however, the paths between positive expectations and heavy drinking are not fully mediated by reasons for drinking. There is a positive direct path between positive expectations and frequency of heavy drinking (.12). The powerful effect of social reasons for heavy drinking on the frequency of heavy drinking is consistent with prior studies (Cooper et al., 1988; Cronin, 1997) but only partially mediates the association between positive expectation and heavy drinking. Negative expectations, however, are fully mediated by escape reasons for drinking.

As expected, there is a strong positive path between the frequency of heavy drinking and alcohol dependence (.65). As shown in Table 3, the nonethnic demographic associations with the frequency of heavy drinking are unrelated (directly) to alcohol dependence, which is consistent with the analysis reported by Hilton (1987). The paths between the cognitive domains, however, include both direct and indirect associations with alcohol dependence. The association between negative expectations and alcohol dependence (.16) is only partially mediated by escape reasons for drinking. Moreover, some of these direct effects take on signs opposite to the corresponding indirect effects. As shown in Figure 1a, there are positive indirect effects for social reasons for drinking and alcohol dependence (.52 between social reasons and heavy drinking and .65 between heavy drinking and dependence), whereas the direct effect between social reasons and alcohol dependence is negative (-.20). Therefore, the association between heavy alcohol use and dependence, although positive, is complex and may also be moderated by other factors not included in the present analysis. Further, not all heavy drinkers develop alcohol dependence, and among those that do develop dependence, social reasons may be relatively less powerful motivators than escape reasons for drinking. Future studies need to differentiate cognitive influences between nondependent heavy drinkers and alcohol-dependent drinkers and suggest appropriate therapeutic strategies for these two groups. In view of the established risk between heavy drinking and alcohol dependence, the presence of positive expectancies and social reasons for drinking needs to be addressed in targeted interventions for nondependent heavy drinkers.

Another explanation for the complex associations seen may be the cross-sectional design of the present study, which cannot assess directionality. It could be argued that both negative expectations and escape reasons for drinking are consequences of alcohol dependence or that these prior cognitions are both initial paths in the development of drinking patterns but may also be consequences of alcohol dependence. Another limitation besides lack of causal certainty is that reasons and expectancies were treated as conceptually distinct here; empirically, they may not have the assumed ordering, which was based on considering that reasons are more proximally related to intake than expectancies, however plausible this may appear.

Although studies on alcohol-related cognitions have generally ignored ethnic differences, the present study, with large ethnic minority oversamples, contributes to the sparse literature in this area (Caetano, 1984; Caetano and Medina Mora, 1990; Herd, 1985). As shown in Figure 1b, black compared with non-Hispanic white respondents exhibited both indirect effects through heavy drinking and direct effects for alcohol dependence, although the negative indirect effect (-.21) takes on a sign opposite to the corresponding direct effect (.46) and suggests that the lower frequency of heavy drinking among blacks actually suppresses, rather than strengthens, their direct effects on alcohol dependence. Although blacks are less likely to drink heavily than whites, once they do, they are more likely to develop alcohol dependence. The association between heavy alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence differs among white and black populations and is independent of cognitive domains (there were no significant associations between black race and either expectations or reasons for drinking). Among Hispanics compared with white non-Hispanic respondents, the association with alcohol dependence is only partially mediated by heavy drinking. Further, the associations between Hispanic ethnicity and cognitive domains (positive expectancies and social reasons) are negative, in contrast to the positive associations with heavy drinking and alcohol dependence. These ethnic differences may be important indicators of cultural differences in the development of alcohol expectancies and drinking patterns and cognitions related to reasons for drinking.

Several ethnic group differences in some of the measurement models were observed. For example, blacks showed a higher likelihood of reporting “feeling sick” as a negative expectation of drinking and also higher probabilities of reporting “getting high” or “getting drunk” in the heavy drinking construct compared with white respondents. Possibly both these results could be explained if the quantities per occasion that black respondents typically drank when drinking heavily were higher than the amounts drunk by whites, which would likely affect both their expectancies of a drinking event and the subjective intoxication state measurement coefficients in the heavy drinking construct. For example, distilled spirits drinks were found to be large at bars frequented by black patrons in a Northern California study (Kerr et al., in press). Regarding ethnic differences in the path coefficients in Figure 1b, both ethnic minority groups compared with whites have stronger direct effects on alcohol dependence. Together with several differences in the dependence measurement models for black versus white respondents, it appears that the construct “alcohol dependence” has a somewhat different meaning in these groups and that both ethnic minorities are overall more likely to report dependence symptoms, for reasons still not well understood. The differences between racial/ethnic subgroups on item responses indicate the need to direct attention to the importance of conducting more specific future analyses in these subgroups.

Several important limitations in this study must be noted. The cross-sectional design of the study limits interpretations of directionality among cognitions and drinking experiences. The absence of standardized questionnaires related to alcohol expectancies found in the literature is a further limitation, although items included here have similar content to other widely used scales (Schafer and Leigh, 1996). In addition, other studies based on limited measures of expectancy (Stacy et al., 1990) have found comparable predictability related to drinking measures. A further limitation in the present study is the use of global assessments of positive and negative expectancies. Leigh and Stacy (1993) reported significant associations between drinking and specific expectances for social facilitation and fun. Much of the literature on alcohol expectancies draws on college student populations, and the use of a general population sample in the present study serves to extend this literature.

In planning prevention and intervention programs, it is important to understand ethnic differences in the etiology of heavy drinking and alcohol dependence. Here, the large oversamples of black and Hispanic individuals permitted assessment of some important cognitive factors associated with problem drinking and alcohol dependence. In developing national alcohol policies, particularly those designed to enhance access to and reform of alcohol-related health services, we need to take into account the existing health disparities in ethnic minority populations in the United States (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2001; Schmidt et al., 2007), but we also need to understand the distinct ways in which alcohol problems may be developed and maintained in these ethnic minority populations. For this, basic epidemiological data for the groups in question are essential (Greenfield, 2001; Schmidt et al., 2006). But before we can properly address health disparities in these important subgroups, we need to better understand the varying course of alcohol problems and alcohol dependence. The present analysis represents a beginning, but for a more complete understanding, longitudinal work on cognitive domains and minority groups will be crucial (Caetano and Kaskutas, 1996).

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant P30 AA05595 awarded to the Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute. A version of this paper was presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, Philadelphia, PA, November 9–13, 2002.

References

- Abbey A, Smith MJ, Scott RO. Relationship between reasons for drinking alcohol and alcohol consumption: An interactional approach. Addict. Behav. 1993;18:659–670. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Creamer VA, Stetson BA. Adolescent alcohol expectancies in relation to personal and parental drinking patterns. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1987;96:117–121. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Goldman MS, Inn A, Anderson LR. Expectations of reinforcement from alcohol: Their domain and relation to drinking patterns. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1980;48:419–426. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. Ethnicity drinking in Northern California: A comparison among whites, blacks and Hispanics. Alcohol Alcsm. 1984;19:31–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark C. Trends in alcohol consumption patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1995. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1998;59:659–668. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL, Greenfield TK. Prevalence, trends, and incidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms: Analysis of general population and clinical samples. Alcohol Hlth Res. World. 1998;22:73–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Kaskutas LA. Changes in drinking problems among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984-1992. Subst. Use Misuse. 1996;31:1547–1571. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Medina Mora ME. Reasons and attitudes toward drinking and abstaining: A comparison of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. Rock-ville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute on Drug Abuse. Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse: Community Epidemiology Work Group Proceedings, June 1990. 1990:173–191.

- Caetano R, Raspberry K. Drinking and DSM-IV alcohol and drug dependence among White and Mexican-American DUI offenders. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2000;61:420–426. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Tam TW. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV and ICD-10 alcohol dependence: 1990 U.S. National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Alcsm. 1995;30:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Tam T, Greenfield T, Cherpitel C, Midanik L. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and drinking in the U.S. population: A risk analysis. Ann. Epidemiol. 1997;7:542–549. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D, Cisin IH, Crossley HM. American Drinking Practices: A National Study of Drinking Behavior and Attitudes, Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies Monograph No. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Drinking to cope with negative affect and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders: A test of three alternative explanations. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1999;60:694–704. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, George WH. Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1988;97:218–230. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin C. Reasons for drinking versus outcome expectancies in the prediction of college student drinking. Subst. Use Misuse. 1997;32:1287–1311. doi: 10.3109/10826089709039379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber PD, Khavari KA, Douglass FM., 4th A factor analytic study of reasons for drinking: Empirical validation of positive and negative reinforcement dimensions. J. Clin. Cons. Psychol. 1980;48:780–781. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.6.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Wilsnack R, Dawson D, Vogeltanz N. Should alcohol consumption measures be adjusted for gender differences. Addiction. 1998;93:1137–1147. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93811372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK. Evaluating competing models of alcohol-related harm. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22(Suppl. No. 2):52s–62s. doi: 10.1097/00000374-199802001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK. Washington, DC: Academy for Health Services Research and Health Policy, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Health Disparities in Alcohol-Related Disorders, Problems, and Treatment Use by Minorities. FrontLines: Linking Alcohol Services Research and Practice June 2001. 2001:3–7.

- Greenfield TK, Kerr WC. Alcohol measurement methodology in epidemiology: Recent advances and opportunities. Addiction. 2008;103:1082–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. A ten-year national trend study of alcohol consumption 1984-1995: Is the period of declining drinking over? Amer. J. Publ. Hlth. 2000;90:47–52. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. The Socio-Cultural Correlates of Drinking Patterns in Black and White Americans: Results from a National Survey. San Francisco, CA: University of California, San Francisco; 1985. Ph.D. Dissertation, [Google Scholar]

- Hilton ME. Demographic characteristics and the frequency of heavy drinking as predictors of self-reported drinking problems. Brit. J. Addict. 1987;82:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: A ten-year model. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2001;62:190–198. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Midanik LT. How many drinks does it take you to feel drunk? Trends and predictors for subjective drunkenness. Addiction. 2006;101:1428–1437. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Patterson D, Koenen MA, Greenfield TK. Large drinks are no mistake: Glass size, not shape, affects alcoholic beverage drink pours. Drug Alcohol Rev. in press doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knupfer G. The risks of drunkenness (or ebrietas resurrecta): A comparison of frequent intoxication indices and of population subgroups as to problem risks. Brit. J. Addict. 1984;79:185–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knupfer G, Fink R, Clark WB, Goffman AS. Factors Related to Amount of Drinking in an Urban Community. California Drinking Practices Study, Report No. 6. Berkeley, CA: California State Department of Public Health; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Lang AR, Patrick CJ, Stritzke WGK. Alcohol and emotional response: A multidimensional-multilevel analysis. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 2nd Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 328–371. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. Attitudes and expectancies as predictors of drinking habits: A comparison of three scales. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1989a;50:432–440. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. In search of the Seven Dwarves: Issues of measurement and meaning in alcohol expectancy research. Psychol. Bull. 1989b;105:361–373. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stacy AW. Alcohol outcome expectancies: Scale construction and predictive utility in higher-order confirmatory models. Psychol. Assess. 1993;5:216–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MJ, Lockmuller JC. Alcohol reinforcement: Complex determinant of drinking. Alcohol Hlth Res. World. 1990;14:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JK, Blum TC, Roman PM. Drinking to cope and self-medication: Characteristics of jobs in relation to workers' drinking behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1992;13:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Midanik L. Drunkenness, feeling the effects, and 5+ measures. Addiction. 1999;94:887–897. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94688711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT. Definitions of drunkenness. Subst. Use Misuse. 2003;38:1285–1303. doi: 10.1081/ja-120018485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. A structural model with latent variables. J. Amer. Stat. Assoc. 1979;74:807–811. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Dichotomous factor analysis of symptom data. Sociol. Meth. Res. 1989;18:19–65. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide, Version 4. Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Version 3.1. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Tam T, Muthén L, Stolzenberg R, Hollis M. Latent variable modeling in the LISCOMP framework: Measurement of attitudes towards career choice. In: Krebs D, Schmidt P, editors. New Directions in Attitude Measurement. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter; 1993. pp. 277–290. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Forecast for the Future: Strategic Plan to Address Health Disparities. 2001

- Schafer J, Leigh BC. A comparison of factor structures of adolescent and adult alcohol effect expectancies. Addict. Behav. 1996;21:403–408. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L, Greenfield TK, Mulia N. Unequal treatment: racial and ethnic disparities in alcoholism treatment services. Alcohol Res. Hlth. 2006;29:49–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: Results from the national alcohol survey. Alcsm: Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK, Raskin G. Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol use: A latent variable cross-lagged panel study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1996;105:561–574. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Abbey A, Scott RO. Reasons for drinking alcohol: Their relationship to psychosocial variables and alcohol consumption. Int. J. Addict. 1993;28:881–908. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick L, Steele C, Marlatt A, Lindell M. Alcohol-related expectancies: Defined by phase of intoxication and drinking experience. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1981;49:713–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.5.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Widaman KF, Marlatt GA. Expectancy models of alcohol use. J. Pers. Social Psychol. 1990;58:918–928. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus R, Bacon SD. Drinking in College. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]