Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to conduct a temporal examination of the associations among disordered eating behaviors, substance use, and use-related negative consequences in female college students—a population at high risk for developing eating and substance-use disorders.

Method:

Participants completed assessments of disordered eating behaviors, alcohol and drug use, and use-related negative consequences.

Results:

Results support previous research suggesting that disordered eating behaviors are more strongly associated with alcohol- and substance-related problems rather than use per se. With respect to temporal precedence, results indicated that binge eating preceded alcohol-use problems, but a bidirectional relationship was found for vomiting. With regard to drug problems, laxatives use preceded drug problems, whereas drug problems preceded fasting. These associations were not better accounted for by pre-existing eating or substance-use problems or psychiatric distress (e.g., depression, anxiety).

Conclusions:

This study further supports the importance of assessing consequences, in addition to use patterns, when examining substance use in individuals demonstrating threshold and subthreshold eating-disordered behaviors.

This study was designed to extend previous research examining associations between eating disorder symptomatology (binge eating, compensatory vomiting, laxative use, fasting) and substance-use problems (consequences of alcohol and drug use). Research suggests individuals who engage in disordered eating behaviors often suffer from co-morbid psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and substance misuse (O'Brien and Vincent, 2003; Stice, 1999; Striegel-Moore et al., 1999; Zaider et al., 2000). Because depression and anxiety have also been associated with increased substance use (Buckner et al., 2006; Kushner et al., 1990), it has been suggested that these psychiatric symptoms may be partly responsible for the relation between substance misuse and disordered eating (Baker et al., 2007; Dansky et al., 2000). Thus, it is important to account for depression and anxiety when examining associations between the two.

Numerous investigations of the association between disordered eating and substance use in clinical and subclinical populations report women who engage in disordered eating behaviors have a higher rate of substance use than their asymptomatic counterparts and there is a higher frequency of problematic eating behaviors in individuals with substance use disorders (Corcos et al., 2001; Holderness et al., 1994; Krahn et al., 2005; Schuckit et al., 1996). However, many of these studies suffer from methodological problems, resulting in variable prevalence rates.

One methodological limitation inherent in these studies is the failure to distinguish between various substances, resulting in the grouping of alcohol and illicit drugs into the same category. Combining substances into a single category erroneously assumes that individuals who use alcohol and those who use other drugs constitute a homogeneous population (Dansky et al., 2000) and renders it nearly impossible to draw conclusions about the strength of the association between disordered eating and problematic use of each substance. In addition, women with current eating problems are often grouped with those who report past symptomatology, and women with a history of substance use are often grouped with those who report current use.

An additional weakness of the literature is that very few studies have investigated the relation between disordered eating and substance use-related consequences. This is an important distinction, because individuals who are not frequent substance users may still experience severe substance-related problems, such as being fired from a job; being arrested because of drug or alcohol use; or missing school, work, or social events with friends or family as a result of being drunk or high (Wechsler et al., 2000). The few studies that have assessed the negative consequences of substance use have found women who engage in disordered eating behaviors report significantly more alcohol- and drug-related negative consequences than their asymptomatic counterparts (Adams and Araas, 2006; Anderson et al., 2005; Dams-O'Conner and Martens, 2005; Ross and Ivis, 1999). Our previous research (Dunn et al., 2002) indicates this appears to be true even when they do not report using substances more frequently or in higher quantities than their non-eating-disordered peers. Substance-related consequences reported by individuals who engage in disordered eating behaviors involve both short-and long-term difficulties, which traverse multiple domains: interpersonal, intrapersonal, legal, and occupational (Dunn et al., 2002). Thus, information about the quantity/frequency of alcohol and drug use alone may not be sufficient to identify high-risk substance use in this population. Because substance use and use-related consequences are not identical, it is important to assess both to better understand specific characteristics of the relation between eating disorder symptoms and substance use.

Finally, the cross-sectional nature of many studies allows only for descriptive data concerning the prevalence of individuals with concurrent eating and substance-use problems. Few studies have investigated the temporal relationship between disordered eating behaviors and substance use, which would allow for a better understanding of the influence of one problematic behavior on the other. Wiseman et al. (1999) focused on the potential impact of the developmental sequence of these problems in patients seeking treatment for an eating disorder. Those with comorbid substance dependence were asked to indicate which disorder developed first and then were categorized into two groups: eating disorder predated the substance use, or substance use predated the eating disorder. Individuals whose substance use predated their eating disorder reported the use of more substances. However, patients whose eating disorder predated their substance use had the greatest number of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses.

In the only prospective study to date, Franko et al. (2005) examined the bidirectional influence of patients' eating disorder on their alcohol use. The results indicated neither a history of an alcohol-use disorder nor current alcohol use influenced time to recover from an eating disorder. However, a number of disordered eating behaviors (e.g., vomiting, compulsive exercise, and overconcern with weight and shape) were shown to influence time to recover from an alcohol-use disorder. The authors preliminarily concluded the influence of disordered eating behaviors on alcohol use appears to be greater than the reverse. However, more research is needed to tease apart the influence of these problem behaviors on each other.

The aforementioned study also raises an important issue regarding the assessment of disordered eating behaviors. Research suggests that individuals who engage in binge eating are qualitatively different from those who primarily restrict their intake and from normal weight controls (Williamson et al., 2005; Wonderlich et al., 2007). There is also growing evidence that purging, both in the presence and absence of binge eating, is prognostically and clinically significant. That is, purging has been associated with lower treatment recovery rates, and individuals who purge but do not binge have been described as distinct from other eating-disordered individuals (Keel, 2007; Keel et al., 2005; Milos et al., 2005; Mond et al., 2006). Thus, it is potentially more relevant to group individuals based on the presence/severity of particular symptomatology (e.g., bingeing, purging) than by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), diagnosis.

In sum, the association between disordered eating behaviors and substance use has been well researched, but relatively few studies have considered substance use-related negative consequences, and even fewer have investigated the temporal association between these problems. Thus, the purpose of this study was to conduct a cross-lagged evaluation of disordered eating behaviors, substance use, and use-related consequences in non-treatment-seeking female college students, a population at high risk for developing eating and substance-use disorders.

Method

Participants

This study consists of secondary data analyses from two waves of a multisite, multiyear, Web-based study of college student drinking. Once enrolled, students were followed annually until graduation. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied. In Year 1, 9,751 women were invited to participate and 39.3% (n = 3,829) responded. Of the 3,829 Year 1 respondents, 54.6% (n = 2,090) were retained in Year 2. Of the 1,739 individuals who did not complete Year 2 assessments, 52.9% (n = 920) were seniors at baseline, the majority of whom likely graduated before the Year 2 assessment. Among individuals who at baseline were freshman, sophomores, or juniors, 68.8% were retained at 1-year follow-up. Thus, the sample used for the present analyses included 2,090 female students who completed assessments during two consecutive waves of data collection.

At baseline, 26.8% were freshman, 27.7% sophomores, 32.3% juniors, and 13.1% seniors. The majority identified themselves as white (74.2%), with Asian/Pacific Islander (16.6%), Hispanic/Latino (2.5%), Native American (1.0%), black (.8%), and other (4.8%) comprising the rest of the sample. The majority of participants identified themselves as heterosexual (94%), with the rest endorsing bisexual (3.8%), lesbian (0.9%), gay (0.1%), or questioning (1.1%). The mean (SD) age of participants was 20 (3.44) years.

In general, the results indicate that our sample was de-mographically representative of the populations from which they were drawn. One notable exception was age; the mean age of our sample was slightly lower than the average age of undergraduate women on each campus, although median and modal ages were comparable. A likely explanation is that we intentionally oversampled freshman and undersampled seniors to increase our chances of having multiyear data for as many participants as possible (because students were followed until graduation).

Procedures

Participants were selected through obtaining a random sample of enrolled students from the registrar's office on each campus. Letters were mailed providing participants with information about the study and instructions for completing informed consent and assessments online using 128-bit encryption. Nonresponders received email and postcard reminders, followed by a mailed survey packet and an additional reminder email or postcard. Partial completers (who began but did not complete the assessment online) were telephoned to remind them to complete and submit the survey. All measures and procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at each site. As an incentive for participation each year, individuals received their choice of entry into a drawing for a $ 1,000 gift certificate to the store of their choice, a $10 check, or two movie tickets (approximate value = $16.50).

Measures

The full assessment included numerous measures of college student drinking and eating and took 45-60 minutes. Only measures relevant to the current study are described.

Demographic information included participant age, birth gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, height, and weight. Height and weight were used to calculate body mass index.

Eating behaviors were assessed using the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS; Stice et al., 2000). The EDDS is a 20-item self-report measure designed to yield DSM-IV diagnoses of bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. The EDDS has excellent concordance with interview diagnoses (Stice et al., 2000). Single items, examining the frequency of each disordered eating behavior (e.g., vomiting, fasting, binge eating, laxative use), were used as independent measures for each symptom.

Alcohol use was assessed via the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985). Participants filled in seven boxes with numbers representing their typical drinking on each day of the week, averaged over the past 3 months. The 3-month estimation minimizes fluctuations resulting from variability in social calendars in a given month and provides a more stable estimate of drinking rates. The DDQ has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and convergent validity with measures of drinking (Baer et al., 1991; Borsari and Carey, 2000; Neighbors et al., 2004, 2006). In this study, alcohol use reflects the number of standard drinks consumed per week, on average, over the past 3 months.

Alcohol-related consequences were assessed using a modified version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989). The RAPI asks students to rate the frequency of 23 items reflecting alcohol's impact on social and health functioning over the past 6 months. Sample items include, “Not able to work or study for a test,” “Caused shame or embarrassment,” and “Was told by a friend or neighbor to stop or cut down on drinking.” Two items were added to assess the frequency of driving after consuming two or more drinks and after consuming four or more drinks. Response options range from 1 = never to 5 = more than 10 times. RAPI scores were computed as the sum of the 25 items (α = .88). This scale is highly reliable and accurately discriminates between normal and clinical samples (White and Labouvie, 1989).

Drug use and use-related consequences were both assessed using the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR; Brown et al., 1998). The CDDR was originally developed as an interviewer-administered measure but has been previously used as a self-report instrument with college student samples (Schafer and Brown, 1991). The CDDR was designed to assess the frequency of drug use and use-related negative consequences (Brown et al., 1998). Questions within these domains are assessed for both the past 3 months and lifetime use. For the current study, drug use frequency during the past 3 months and severity of use-related consequences (α = .84) were used.

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed using a modified version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis and Spencer, 1982). The BSI is a 53-item psychological symptom inventory. Respondents indicate on a 5-point scale how distressed they are by various problems. The BSI yields nine primary symptom scale scores and a global index of distress. The anxiety and depression subscales, common comorbid conditions of eating disorders, were used to measure the severity of psychiatric distress (α = .90 and .82, respectively). The psychometric properties of the BSI are well established (Derogatis and Spencer, 1982).

Analytic strategy

Data were analyzed using path analysis in a cross-lagged panel design (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Shadish et al., 2002). This approach allows for evaluation of temporal precedence between constructs by controlling for their cross-sectional association and for the stability of each individual construct. In this context, tests of parameter coefficients for cross-lagged associations provide a conservative test representing the proportion of change in one construct that is uniquely the result of the other construct.

Primary analyses were conducted using AMOS 4.0 (Ar-buckle and Wothke, 1999). The advantages of this approach are the availability of indices evaluating overall model fit and a state-of-the-art approach for handling missing responses. Model fit was evaluated with the Normed Fit Index (NFI; Bentler and Bonett, 1980), Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne and Cudeck, 1993). Values greater than .95 on the NFI and CFI indicate good fit. RMSEA values less than .05 indicate good fit, values around .08 indicate reasonable fit, and values greater than .10 indicate poor fit (Browne and Cudeck, 1993).

Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation is considered a best practice for the treatment of missing data, allowing estimation of means, variances, and covariances using full information without imputing missing values (Schafer and Graham, 2002). However, in most cases where FIML or Multiple Imputation are described as appropriate for making interpretations about longitudinal associations among individuals who are missing assessment points, individuals have contributed more than one assessment point (Shafer and Graham, 2002; Streiner, 2002). Because in this study there were only two assessment points, no dropouts had more than one assessment point; thus, we did not include these participants in the results.

Analyses were conducted systematically examining temporal stability and cross-lagged relations between disordered eating behaviors (bingeing, vomiting, laxative use, and fasting) and substance use (alcohol use quantity; drug use frequency) or substance use-related consequences (alcohol problems and drug problems), controlling for baseline depression and anxiety.

Results

Attrition analyses

Attrition analyses were conducted examining differences in age, ethnicity, substance use, disordered eating behaviors, depression, and anxiety at Year 1 between women who did and did not complete the assessment at Year 2. Results indicated that women who completed the Year 2 assessment were younger (20.12 vs 22.38, p < .001) and were less likely to be white (73.3% vs 76.5%, p < .05) and more likely to be Asian (16.4% vs 12.0%, p < .001) but did not differ with respect to other ethnicities. Completers also reported fewer drinks per week (4.60 vs 3.96, p < .05), less substance use (the average difference in prevalence across substances was 7.9%; all p < .001), less laxative use (.050 vs .158, p < .001), and marginally fewer alcohol problems (3.53 vs 3.92, p = .05). No significant differences were found for drug problems, vomiting, bingeing, fasting, or mood or anxiety symptoms. Thus, with respect to the primary variables of interest in this study (i.e., alcohol- and substance-use problems and disordered eating behaviors), the present sample underrepresented those with more alcohol problems and laxative use.

Preliminary analyses

Results indicated that 25.5% of participants reported engaging in one or more disordered eating behaviors (e.g., binge eating, vomiting, fasting, or laxative use) weekly during the past 3 months. No differences were found at baseline between participants who engaged in disordered eating behaviors and those who did not for age, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. However, women who engaged in disordered eating behaviors reported higher depression and anxiety (t = 10.82, 2,046 df, p < .001; t = 8.04, 2,046 df, p < .001, respectively) than their asymptomatic peers.

At the initial assessment, 17.6% of participants indicated that they were currently abstaining from alcohol, and 9.6% had never tried alcohol; thus, 72.8% were current alcohol users. The most commonly reported drug used at the initial assessment was cannabis, with 43.9% reporting lifetime use. Prevalence of lifetime use was considerably lower for other substances: hallucinogens (15.7%), opiates (11.9%), barbiturates (8.5%), amphetamines (6.5%), cocaine (4.9%), and inhalants (4.9%). Means and standard deviations for the number of occasions of alcohol and drug use in the previous 3 months are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for alcohol and drug use variables at each time

| Variable | Time 1 |

Time 2 |

||

| Mean (SD) | Prevalence | Mean (SD) | Prevalence | |

| Alcoholic drinks consumed per week | 3.96 (6.01) | 90.43% | 3.98 (5.14) | 94.55% |

| Marijuana use | 3.13(6.70) | 43.92% | 2.72 (6.41) | 47.61% |

| Barbiturate use | 0.56 (3.34) | 8.47% | 1.80(5.00) | 8.80% |

| Cocaine use | 0.81 (3.53) | 4.93% | 0.54(1.51) | 6.56% |

| Opiate use | 0.71 (2.24) | 11.87% | 0.72 (2.62) | 13.21% |

| Amphetamine use | 0.49 (2.54) | 6.51% | 0.31 (1.04) | 6.36% |

| Hallucinogen use | 0.24 (.85) | 15.65% | 0.24(1.62) | 17.37% |

| Inhalant use | 0.12 (.61) | 4.88% | 0.16 (.87) | 4.35% |

Notes: Prevalence values reflect the proportion of students reporting ever having used. Alcohol use reflects the number of standard drinks consumed per week, on average, for the past 3 months. Drug use reflects the number of days used per month, on average, for the past 3 months.

Disordered eating and substance use

Consistent with previous findings (Dunn et al., 2002), results revealed little association between eating behaviors (bingeing, vomiting, laxative use, and fasting) and alcohol use or the use of seven assessed drugs. Specifically, only 8 of 96 comparisons of concurrent (i.e., correlation between T1 symptom and T1 substance use) and prospective (i.e., T1 symptom → T2 substance use; T1 substance use → T2 symptom) associations between eating-disordered behaviors and substance use were statistically significant, as indicated by tests of path coefficients in cross-lagged models (2 of 12 for alcohol; 6 of 84 for drugs). In addition, low prevalence rates for the use of specific substances (e.g., cocaine, inhalants) in this population resulted in unstable parameter estimates in several cases and demand considerable caution when interpreting these limited significant findings. Given the primary focus of this study on alcohol- and substance-use problems, as well as the complexity of reporting these largely null results, we elected to provide a brief summary of the significant associations, for completeness (see Table 2). It is noteworthy that associations were more evident for alcohol use than for drug use, with concurrent relations between alcohol use and both vomiting and fasting, and that temporal findings suggest that use more often preceded disordered eating behaviors than the reverse. Additional details regarding these analyses are available on request.

Table 2.

Significant parameter estimates examining concurrent and prospective relationships between disordered eating behaviors and substance use

| Relationship | β | t | p |

| Vomiting ↔ Alcohol use | .09 | 2.07 | .039 |

| Vomiting → Amphetamine use | .37 | 2.88 | .004 |

| Laxative use ↔ Amphetamine use | .35 | 3.11 | .002 |

| Laxative use ← Opiate use | .21 | 1.98 | .048 |

| Laxative use ← Inhalant use | −.96 | −24.14 | .000 |

| Laxative use ← Amphetamine use | −.70 | −6.15 | .000 |

| Fasting ↔ Alcohol use | .08 | 1.98 | .048 |

| Fasting ↔ Cocaine use | .24 | 2.61 | .009 |

Notes: Bidirectional arrows denote concurrent relationship; unidirectional arrows denote prospective relationship in the direction of the arrow. Alcohol use reflects the number of standard drinks consumed per week, on average, for the past 3 months. Drug use reflects the average number of days used per month, on average, for the past 3 months.

Binge eating.

Binge eating was not associated concurrently or temporally with the use of alcohol or any illicit substance.

Vomiting.

Vomiting was positively associated with concurrent alcohol consumption and prospective amphetamine use.

Laxative use.

Laxative use was not associated concurrently or temporally with alcohol consumption. However, the use of laxatives was positively associated with concurrent amphetamine use. In addition, opiate use was prospectively associated with greater laxative use, whereas inhalant and amphetamine use were prospectively associated with less reliance on laxatives.

Fasting.

Fasting was positively associated with concurrent alcohol consumption, as well as concurrent cocaine use.

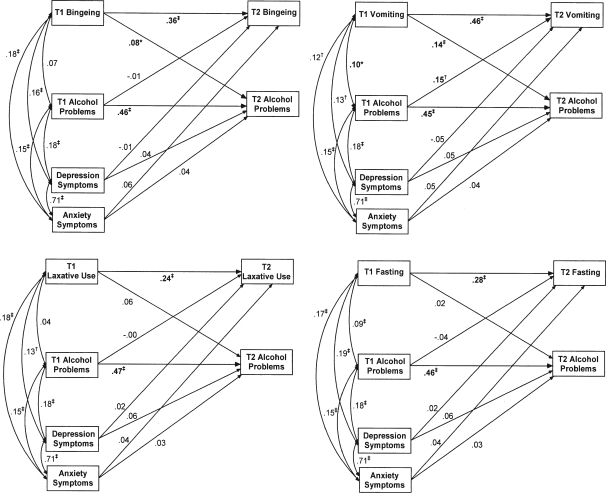

Disordered eating and alcohol problems

Four separate models examined temporal relations among each disordered eating behavior and alcohol problems. Depression and anxiety were included as covariates in all analyses. Table 3 presents estimated means and standard errors for these variables. Estimated means and standard errors were derived from a saturated model, which included Time 1 and Time 2 variables for binge eating, vomiting, laxative use, fasting, alcohol problems, drug problems, and baseline symptoms of depression and anxiety. Standardized parameter estimates for all four models examining cross-lagged associations between disordered eating behaviors and alcohol problems are presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Estimated means and standard errors from Full Information Maximum Likelihood saturated model for eating behaviors and substance-related problems

| Variable | Mean (SE) |

| T1 Binge eating | 1.38 (0.082) |

| T2 Binge eating | 1.20(0.074) |

| T1 Vomiting | 0.14(0.053) |

| T2 Vomiting | 0.14(0.061) |

| T1 Laxative use | 0.05(0.018) |

| T2 Laxative use | 0.07(0.031) |

| T1 Fasting | 0.24 (0.023) |

| T2 Fasting | 0.11(0.012) |

| T1 Alcohol problems | 3.45 (0.121) |

| T2 Alcohol problems | 3.09 (0.123) |

| T1 Drug problems | 1.55 (0.078) |

| T2 Drug problems | 1.47 (0.077) |

| T1 Depression | 0.56(0.016) |

| T1 Anxiety | 0.41 (0.013) |

Notes: T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2.

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged relationships between eating behaviors and alcohol problems. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2. Bold reflects significant findings. *p<.05; †p< .01; ‡p < .001.

Binge eating.

Figure 1 (top left) presents a temporal model of binge eating and alcohol problems, controlling for depression and anxiety symptoms. Model fit indices revealed good overall fit (χ 2 = 5.33, 1 df, p < .05; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .045). Results demonstrated that alcohol problems remained moderately stable over a 1-year period, as did binge eating. Results indicated relatively small but significant concurrent associations between anxiety and depression and bingeing, as well as between psychiatric symptoms and alcohol problems. More importantly, binge eating was associated with increased alcohol problems over time, whereas alcohol problems were not uniquely associated prospectively with binge eating. Neither anxiety nor depression was prospectively associated with binge eating or drinking problems.

Vomiting.

Figure 1 (top right) provides a temporal model of compensatory vomiting and alcohol problems, controlling for depression and anxiety symptoms. Model fit indices revealed reasonably good fit (χ 2 = 2.17, 1 df, p = ns; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .024). Again, the results indicated vomiting was relatively stable across a 1-year period and revealed significant cross-sectional associations among vomiting, alcohol problems, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Moreover, vomiting was associated with increased drinking problems over time, beyond the effects of depression and anxiety. In addition, alcohol problems in Year 1 were found to be associated with increased vomiting for weight control in Year 2.

Laxative use.

Results for a model examining cross-lagged associations between laxative use and alcohol problems, controlling for symptoms of anxiety and depression, are presented in Figure 1 (bottom left). Model fit indices suggested reasonable fit (χ 2 = 8.80, 1 df, p < .01; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .061). Similar to the previous models, significant cross-sectional associations were found between laxative use and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Results also indicated laxatives use remained relatively stable over time. However, in contrast to previous models, laxative use was not prospectively associated with drinking problems, and alcohol problems were not associated prospectively with laxative use.

Fasting.

Figure 1 (bottom right) presents a model examining cross-lagged associations between fasting and alcohol problems, controlling for symptoms of anxiety and depression. Model fit indices suggested marginal fit (χ 2 = 18.80, 1 df, p < .001; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .092). Similar to previous models, fasting was found to have positive and significant cross-sectional associations with alcohol problems and symptoms of depression and anxiety, and fasting remained relatively stable over time. As with laxative use, neither cross-lagged relationship between fasting and alcohol problems was significant.

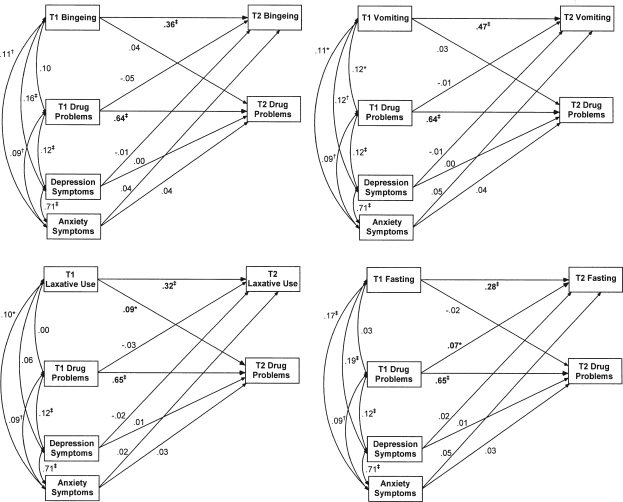

Disordered eating and drug problems

As with alcohol problems, four models examined temporal relations among each disordered eating behavior and drug problems, with depression and anxiety included as covariates in each analysis. Estimated means and standard errors for these variables are displayed in Table 3. Standardized parameter estimates for models examining cross-lagged associations between disordered eating behaviors and drug problems are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cross-lagged relationships between eating behaviors and drug problems. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2. Bold reflects significant findings. *p<.05;†p<.01; ‡p<.001.

Binge eating.

Figure 2 (top left) presents cross-lagged associations between binge eating and drug problems, control ling for symptoms of anxiety and depression (χ 2 = 1.01, 1 df, p = ns; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .003). As in the alcohol models, significant cross-sectional associations were found between binge eating and symptoms of depression and anxiety, and between these psychiatric symptoms and drug use problems. Results also indicated that binge eating and drug use problems were relatively stable over time. However, in contrast to results examining temporal relations between binge eating and alcohol problems, binge eating was not found to be associated with unique variance in prospective drug use problems. Moreover, current drug use problems were not significantly associated with prospective binge eating.

Vomiting.

Cross-lagged associations between vomiting and drug problems are presented in Figure 2 (top right). Overall model fit was good (χ 2 = 3.16, 1 df, p = ns; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .032). As in the alcohol model, significant cross-sectional associations were found among vomiting, drug use problems, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Results also indicated that vomiting and drug problems were relatively stable across a 1-year period. However, vomiting was not uniquely associated with increased drug problems over time, and drug use problems were not associated with increases in compensatory vomiting.

Laxative use.

Results for the examination of cross-lagged relationships between laxative use and drug problems are presented in Figure 2 (bottom left). Model fit indices revealed good fit (χ 2 = 1.58, 1 df, p= ns; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .016). As in previous models, results demonstrated that laxative use and drug problems were relatively stable over time. Interestingly, in contrast to all previous models, laxative use was found to be associated only with concurrent anxiety but not depression. Moreover, in contrast to the alcohol model, wherein no temporal relations were found between laxative use and alcohol-related problems, laxative use was associated with increased subsequent drug use problems, although drug use problems were not associated with prospective laxative use.

Fasting.

Finally, cross-lagged relationships between fasting and drug problems are presented in Figure 2 (bottom right). Model fit indices suggested good fit (χ 2 = 4.52, 1 df, p < .05; NFI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .041). Similar to previous models, results indicated cross-sectional relationships between fasting and psychiatric symptoms, and both fasting and drug problems demonstrated stability over time. However, in contrast to each of the previous models regarding negative consequences, drug problems were associated with increased fasting behavior, whereas fasting was not associated with prospective drug use problems.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to extend previous research by investigating the temporal association among disordered eating behaviors, substance use, and use-related consequences in a non-treatment-seeking sample of female college students. Results are relatively consistent with previous research suggesting stronger associations between disordered eating behaviors and substance-use problems rather than use per se (Dunn et al., 2002). In these data, 8 of 76 (10%) associations were found between eating behaviors and use, whereas 5 of 16 (31%) were found between disordered eating behaviors and use-related consequences.

With regard to alcohol, binge eating was not related to alcohol use; yet purging and fasting were associated with concurrent, but not prospective, alcohol use. However, both bingeing and purging were associated with prospective alcohol problems. These results support research that found that women who met criteria for an eating disorder reported more negative consequences of alcohol use, despite not drinking more frequently or in higher quantities than their asymptomatic peers (Dunn et al., 2002). They also support research findings that the presence of an alcohol-use disorder did not influence recovery from an eating disorder, but disordered eating symptoms (i.e., vomiting, overconcern with weight and shape) predicted onset and recovery from an alcohol-use disorder (Franko et al., 2005). Increased use-related consequences in a disordered eating population may be indicative of alcohol differentially affecting women who binge or who engage in weight-control strategies (i.e., use may result in loss of control over eating, alcohol effects may be felt more quickly or intensely if consumed on an empty stomach).

It is important to note that the relation between vomiting and alcohol in the current study is relatively complex in that there was a bidirectional relationship between vomiting and alcohol consequences. Specifically, the use of vomiting as a weight-control method at Time 1 was associated with increased negative consequences of drinking at Time 2, and alcohol problems at Time 1 were associated with increased vomiting for weight control at Time 2. This latter finding might be explained by the need for individuals who are struggling with disordered eating cognitions (e.g., overconcern about shape or weight) to use vomiting to compensate for increased caloric intake as a result of drinking or as a way to cope with anxiety or negative affect (Keel et al., 2005) stemming from alcohol-related problems (e.g., fights with friends or family).

With regard to illicit drugs, bingeing was not associated with concurrent or prospective drug use or with drug use problems. Moreover, no relations were observed between disordered eating behaviors and the use of marijuana, the most commonly reported drug used in this sample, despite reported effects of marijuana on appetite enhancement (Lee et al., 2007), which one might expect to deter some women from its use for fear of weight gain. Analyses examining associations among disordered eating behaviors and the use of less frequently endorsed substances should be interpreted cautiously but suggest that vomiting, fasting, and laxative use were more strongly associated with the use of stimulants compared with other drugs.

The association between inappropriate weight-control methods and stimulant use is not surprising, because stimulants have appetite suppressant effects and, therefore, are often used by eating-disordered individuals to control their weight. In fact, a recent investigation of drug abuse in women with eating disorders (Herzog et al., 2006) found cocaine and amphetamines to be the two most commonly abused substances in a treatment-seeking sample of women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Similarly, Dams-O'Connor and Martens (2005) reported substance use increased across the continuum of disordered eating behaviors, with those who engaged in “unhealthy” weight loss methods reporting a higher frequency of cocaine and amphetamine use than participants who were not trying to lose weight or who were using “healthy” weight loss strategies. Moreover, strong associations were reported between the risk for an eating disorder and lifetime use of cocaine and amphetamines in a nationally representative sample of Canadian women (Gadalla and Piran, 2007).

The lack of association between bingeing and substance use in the current study mirrors that found in a previous investigation of college students (Dunn et al., 2002) and research conducted in community samples (Dansky et al., 2000; Welch and Fairburn, 1996) and with adolescents (Stock et al., 2002) but is not in line with findings from other studies that report higher rates of substance use in bulimic individuals than in anorexic or asymptomatic individuals (Braun et al., 1994; Franko et al., 2005; Herzog et al., 2006; Holderness et al., 1994; Nagata et al., 2002; Wiederman and Pryor, 1996). It is important to note that the current investigation focused on the relation between substance use and specific disordered eating behaviors, rather than on any particular diagnostic group (e.g., bulimia nervosa), because the majority of individuals who struggle with disordered eating do not meet full diagnostic criteria for anorexia or bulimia nervosa (Fairburn and Bohn, 2005; Herzog et al., 2006; Mitchell et al., 2005).

It is apparent that the relation between eating disorders and substance-use disorders is complex and depends on which substance, disordered eating behavior, and substance-related outcome (i.e., use or use-related problems) is focused on. This complexity might explain some of the inconsistencies in prevalence rates and strengths of association reported previously in the literature. Although this study addressed many of the specific methodological problems inherent in previous investigations, it has a number of limitations that are important to consider. First is its reliance on self-report assessment measures. Although the chosen self-report measures have been shown to be reliable and valid proxies for interviews (Schafer and Brown, 1991; Stice et al., 2000), interviews are necessary for precise estimation of the frequency and severity of eating, drinking, and drug use behaviors. Second, despite measuring symptoms of depression and anxiety, we did not obtain diagnoses of Axis I or Axis II disorders, which have been previously associated with eating disorders and substance use (Dansky et al., 2000; Kozyk et al., 1998).

It is also important to acknowledge that, although examination of the temporal relations among eating disorder symptoms and substance-use problems in this population offers important and unique information, effect sizes were invariably small. With respect to substance use and use-related problems, this may be the result, in part, of the high stability from Time 1 to Time 2, which makes it difficult to find a significant cross-lagged association when controlling for baseline measures. Larger effects might be evident over a period longer than 1 year. In addition, attrition analyses revealed that the sample was underrepresentative with respect to substance use, alcohol problems, and laxative use, as well as overrepresentative of participants identifying as being of white or Asian ethnicity. More generally, despite the large study sample (which might increase confidence in external validity), the use of a college student sample, low recruitment, and high attrition rates limit the generalizability of these findings. Finally, we must acknowledge potential problems with assessment frequency. Research assessments were completed annually; more frequent assessments may have provided more accurate information regarding participant eating and substance-use behaviors. Despite these limitations, this investigation represents a valuable contribution to the literature via its prospective examination of the association among disordered eating, substance use, and use-related consequences.

In sum, the present findings indicate modest associations between disordered eating behaviors and negative consequences resulting from alcohol and drug use among collegiate women and suggest that temporal precedence depends on the particular symptoms and substances assessed. Because the combination of problematic substance use and disordered eating is potentially deadly (Keel et al., 2003), both substance use and use-related consequences should be assessed and continuously monitored in individuals engaging in disordered eating behaviors. Moreover, research on the development and implementation of integrated treatment programs for women with concurrent eating and substance-use disorders is warranted.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01AA012547 awarded to Mary E. Larimer.

References

- Adams TB, Araas TE. Purging and alcohol-related effects on college women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006;39:240–244. doi: 10.1002/eat.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DA, Martens MP, Cimini MD. Do female college students who purge report greater alcohol use and negative alcohol-related consequences? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005;37:65–68. doi: 10.1002/eat.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 User's Guide. Chicago, IL: SmallWaters; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JH, Mazzeo SE, Kendler KS. Association between broadly defined bulimia nervosa and drug use disorders: Common genetic and environmental influences. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007;8:673–678. doi: 10.1002/eat.20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun DL, Sunday SR, Halmi KA. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with eating disorders. Psychol. Med. 1994;24:859–867. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Myers MG, Lippke L, Tapert SF, Stewart DG, Vik PW. Psychometric evaluation of the customary drinking and drug use record (CDDR): A measure of adolescent alcohol and drug involvement. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1998;59:427–438. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Eggleston AM, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: The mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behav. Ther. 2006;37:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-Experimentation Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Corcos M, Nezelof S, Speranza M, Topa S, Girardon N, Guilbaud O, Taieb O, Bizouard P, Halfon O, Venisse JL, Perez-Diaz F, Flament M, Jeammet PH. Psychoactive substance consumption in eating disorders. Eat. Behav. 2001;2:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(00)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dams-O'Connor K, Martens MP. Substance use and negative consequences along a disordered eating continuum; Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Washington, DC. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dansky BS, Brewerton TD, Kilpatrick DG. Comorbidity of bulimia nervosa and alcohol use disorders: Results from the national women's study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000;27:180–190. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<180::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Spencer PM. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Towson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. Alcohol and drug-related negative consequences in college students with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002;32:171–178. doi: 10.1002/eat.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorders NOS (EDNOS): An example of the troublesome “Not Otherwise Specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005;43:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, Jackson S, Manzo MP, Herzog DB. How do eating disorders and alcohol use disorder influence each other? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005;38:200–207. doi: 10.1002/eat.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla T, Piran N. Eating disorders and substance abuse in Canadian men and women: A national study. Eat. Disord. 2007;15:189–203. doi: 10.1080/10640260701323458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog DB, Franko DL, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, Jackson S, Manzo MP. Drug abuse in women with eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006;39:364–368. doi: 10.1002/eat.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holderness CC, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. Co-morbidity of eating disorders and substance abuse: Review of the literature. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994;16:1–34. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199407)16:1<1::aid-eat2260160102>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK. Purging disorder: Subthreshold variant or full-threshold eating disorder? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2007;40(Suppl):S89–S94. doi: 10.1002/eat.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Kamryn TE, Franko D, Charatan DL, Herzog DB. Predictors of mortality in eating disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 2003;60:179–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Haedt A, Edler C. Purging disorder: An ominous variant of bulimia nervosa? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005;38:191–199. doi: 10.1002/eat.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozyk JC, Touyz SW, Beaumont RJV. Is there a relationship between bulimia nervosa and hazardous alcohol use? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1998;24:95–99. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199807)24:1<95::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn DD, Kurth CL, Gomberg E, Drewnowski A. Pathological dieting and alcohol use in college women: A continuum of behaviors. Eat. Behav. 2005;6:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MC, Sher KJ, Beitman BD. The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. Amer. J. Psychiat. 1990;147:685–695. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Woods BA. Marijuana motives: Young adults' reasons for using marijuana. Addict. Behav. 2007;32:1384–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milos G, Spindler A, Schnyder U, Fairburn CG. Instability of eating disorder diagnoses: Prospective study. Brit. J. Psychiat. 2005;187:573–578. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Cook-Myers T, Wonderlich SA. Diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa: Looking ahead to DSM-V. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005;37(Suppl):S95–S97. doi: 10.1002/eat.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond J, Hay P, Rodgers B, Owen C, Crosby R, Mitchell J. Use of extreme weight control behaviors with and without binge eating in a community sample: Implications for the classification of bulimic-type eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006;39:294–302. doi: 10.1002/eat.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Kawarada Y, Ohshima J, Iketani T, Kiriike N. Drug use disorders in Japanese eating disorder patients. Psychiat. Res. 2002;109:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien KM, Vincent NK. Psychiatric comorbidity in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: Nature, prevalence, and casual relationships. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2003;23:57–74. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE, Ivis F. Binge eating and substance use among male and female adolescents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999;26:245–260. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199911)26:3<245::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Brown SA. Marijuana and cocaine effect expectancies and drug use patterns. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 1991;59:558–565. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol. Meth. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Anthenelli RM, Bucholz KK, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI., Jr Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in alcohol-dependent men and women and their relatives. Amer. J. Psychiat. 1996;153:74–82. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Clinical implications of psychosocial research on bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 1999;55:675–683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199906)55:6<675::aid-jclp2>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL. Development and validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychol. Assess. 2000;12:123–131. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock SL, Goldberg E, Corbett C, Katzman DK. Substance use in female adolescents with eating disorders. J. Adolesc. Hlth. 2002;31:176–182. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. The case of missing data: Methods of dealing with dropouts and other research vagaries. Can. J. Psychiat. 2002;47:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Garvin V, Dohm F-A, Rosenheck RA. Eating disorders in a national sample of hospitalized female and male veterans: Detection rates and psychiatric comorbidity. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999;25:405–414. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199905)25:4<405::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. J. Amer. Coll. Hlth. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch SL, Fairburn CG. Impulsivity or comorbidity in bulimia nervosa: A controlled study of deliberate self-harm and alcohol and drug misuses in a community sample. Brit. J. Psychiat. 1996;169:451–458. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW, Pryor T. Substance use and impulsive behaviours among adolescents with eating disorders. Addict. Behav. 1996;21:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DA, Gleaves DH, Stewart TM. Categorical versus dimensional models of eating disorders: An examination of the evidence. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005;37:1–10. doi: 10.1002/eat.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman CV, Sunday SR, Halligan P, Korn S, Brown C, Halmi KA. Substance dependence and eating disorders: Impact of sequence on comorbidity. Comprehen. Psychiat. 1999;40:332–336. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Joiner TE, Jr, Keel PK, Williamson DA, Crosby RD. Eating disorder diagnoses: Empirical approaches to classification. Amer. Psychol. 2007;62:167–180. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaider TI, Johnson JG, Cockell SJ. Psychiatri c comorbidity associated with eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents in the community. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000;28:58–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200007)28:1<58::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]