Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of acute angle-closure glaucoma resulting from spontaneous hemorrhagic retinal detachment.

Methods

An 81-year-old woman visited our emergency room for severe ocular pain and vision loss in her left eye. Her intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 14 mmHg in the right eye and 58 mmHg in the left eye. Her visual acuity was 0.4 in the right eye but she had no light perception in the left eye. The left anterior chamber depth was shallow and gonioscopy of the left eye showed a closed angle. In comparison, the right anterior chamber depth was normal and showed a wide, open angle. Computed tomography and ultrasonography demonstrated retinal detachment due to subretinal hemorrhage. After systemic and topical antiglaucoma medications failed to relieve her intractable severe ocular pain, she underwent enucleation.

Results

The ocular pathology specimen showed that a large subretinal hemorrhage caused retinal detachment and pushed displaced the lens-iris diaphragm, resulting in secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

Conclusions

Prolonged anticoagulant therapy may cause hemorrhagic retinal detachment and secondary angle-closure glaucoma. If medical therapy fails to relieve pain or if there is suspicion of an intraocular tumor, enucleation should be considered as a therapeutic option.

Keywords: Acute angle-closure glaucoma, Hemorrhage, Retinal detachment

Anticoagulant therapy may cause serious hemorrhagic complications, including subdural hematoma, epistaxis, melena, hematemesis and hematuria. In these circumstances, the bleeding is often associated with a preexisting disorder.1-4 In contrast, ocular complications in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy are uncommon, with subconjunctival hemorrhage being the most common. In addition, Gordan and Mead5 have reported retinal hemorrhage as a complication of anticoagulation therapy.1-4

However, spontaneous hemorrhagic retinal detachment causing acute secondary angle-closure glaucoma is a rare disorder and there have been no case reports in the literature to date in Korea.

We report the first case of acute angle-closure glaucoma caused by spontaneous massive hemorrhagic retinal detachment in Korea.

Case Report

An 81-year old woman visited our emergency room after 2 days of severe ocular pain and loss of vision in her left eye. Her medical history included a cerebrovascular accident and hypertension and her medications included astrix, plavix and a beta-blocker. For the previous year, she had visited our clinic for visual disturbances due to a cataract but she had refused further evaluation. At that time, her visual acuity was 0.6 in the right eye and 0.4 in the left eye and a fundus examination had not been performed because of the patient's refusal.

Upon visiting our emergency room, her visual acuity was 0.4 in the right eye, but she had no light perception in the left eye. Her intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 14 mmHg in the right eye and 58 mmHg in the left eye. There was moderate conjunctival injection and a fixed mid-dilated pupil in the left eye. The right anterior chamber depth was normal, but the left anterior chamber depth was shallow. Gonioscopy showed a wide-open angle in the right eye, but revealed a closed anterior chamber angle in the left eye. The left cornea was edematous with diffuse microcysts. Posterior segment examination of the right eye was not done because of patient refusal. In the left eye, a large subretinal mass abutting the posterior lens surface was suspected. B-scan ocular ultrasonography and computed tomography (Fig. 1) of the left eye showed a large, irregularly reflective mass that was thought to represent a large subretinal mass.

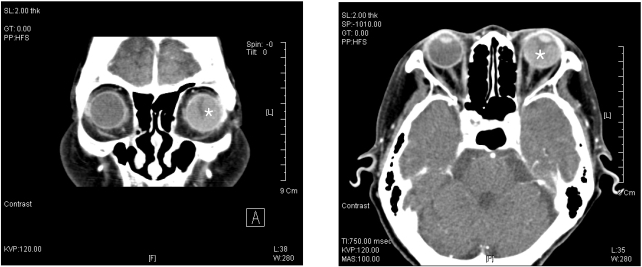

Fig. 1.

Orbital computed tomography with contrast enhancement showed a large hemorrhagic retinal detachment (asterisk) in the left eye.

The patient was treated with intravenous mannitol, oral acetazolamide, and topical betoptic, cosopt®, and pilocarpine. However, these regimens failed to relieve the severe ocular pain and the high IOP persisted. did not decrease. The next day, her blind and painful left eye was enucleated under general anesthesia. An intraocular implant was not inserted and her pain was relieved.

Ocular pathology

The enucleated left eyeball measured 2.5 cm in the antero-posterior dimension and 2.5 cm in vertical length and weighed 5.4 gm. On horizontal section, the shallow anterior chamber and anteriorly displaced swollen lens could be seen (Fig. 2). The cut surface contained a brownish tan colored homogenous gelatinous material. The totally detached retina was adherent to the posterior aspect of the swollen, cataractous lens and a large amount of degenerated blood filled the subretinal and subchoroidal space. Microscopic examination revealed that the anterior chamber was filled with serosanguinous fluid (Fig. 3). The retina was massively detached by degenerated and clotted blood. Blood was also present in the subretinal pigment epithelium.

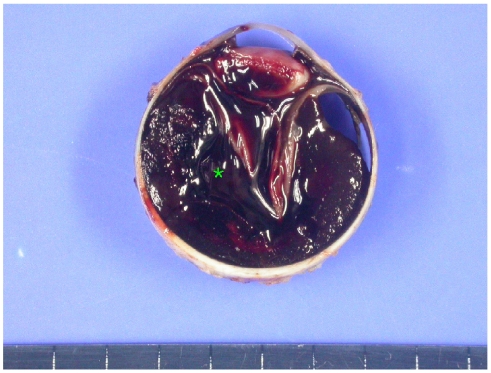

Fig. 2.

The firm left globe was horizontally sectioned. Massive amounts of degenerated blood (asterisk) filled the subretinal space. The totally detached retina touched the posterior surface of the lens and the anterior chamber was shallow.

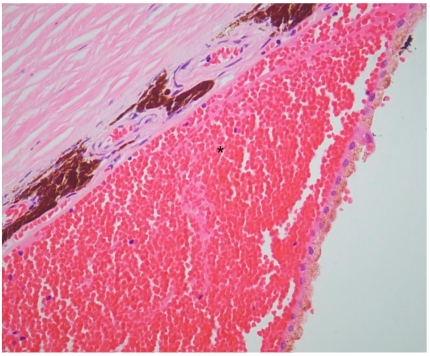

Fig. 3.

Hemorrhagic RPE detachment was found. Blood also filled the subretinal space (asterisk) (hematoxylin-eosin stain: original magnification, ×400).

Discussion

Spontaneous hemorrhagic retinal or choroidal detachment causing acute secondary angle-closure glaucoma is a rare ocular disorder.5 Since Parsons7 first described this entity in 1906, only 22 cases have been reported.1,6,8-11 All of these cases had at least one of the suspicious predisposing factors, including oral anticoagulant therapy at the time of bleeding, a blood dyscrasia, or systemic hypertension. These factors are thought to predispose patients to a massive intraocular hemorrhage.8

The source of the subretinal or choroidal hemorrhage in most reported cases has been suggested to be a macular disciform lesion with subretinal neovascularization.6 However, in our case, preoperative examination failed to reveal macular degeneration in either eye and the ocular pathology specimen did not reveal the source of bleeding. Another report by Kozlowski et al.12 reported massive subretinal hemorrhage with acute angle-closure glaucoma in a case of chronic myleocytic leukemia. They suggested that ocular hemorrhage in leukemia might be related to the invasion of vessel walls by leukemic cells or abnormalities in blood clotting mechanisms.

The proposed mechanism for the angle-closure is the abrupt forward displacement of the lens-iris diaphragm, resulting from a massively detached choroid and retina. The section of globe in our case showed that blood in the subretinal space had pushed the retina anteriorly so that the inner surface had become apposed and the iris was displaced against the cornea, thus obliterating the anterior chamber angle (Fig. 2, 3).

Patients afflicted with this condition usually had either systemic hypertension or a primary or anticoagulant-induced clotting disorder, as in our case. Hemorrhagic retinal detachment and secondary angle-closure glaucoma are potential complications of anticoagulation therapy.6-11 Carorina et al.13 documented a case of bilateral subretinal hemorrhage as a complication of warfarin therapy, causing bilateral non-pupillary block angle-closure glaucoma in a patient with bilateral nanophthalmos. Impaired local hemostasis is responsible for the uncontrolled bleeding and could be a predisposing factor for massive hemorrhage complicating macular degeneration. According to the literature14, 19-27% of patients with hemorrhagic ophthalmic complications were taking Coumadin or a NSAID.15,16 Other reports have estimated that bleeding as a complication of long long-term anticoagulant therapy occurs in up to 40% of ambulatory patients and that 2% to 10% will have a serious hemorrhage.17

When a massive subretinal or choroidal hemorrhage occurs, causing acute secondary angle-closure glaucoma, several underlying abnormalities should be suspected. If a patient has recently undergone intraocular surgery, a massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage may occur. Chen et al.8 observed serial funduscopic and echographic recordings after the initial stage of bleeding in two patients with acute angle-closure glaucoma resulting from spontaneous hemorrhagic retinal detachment. They found that the bleeding did not follow a rapid course as occurs in expulsive suprachoroid hemorrhage in intraocular surgery and did not occur in a hypotensive state. It took about 2 to 4 weeks for the spontaneous bleeding to build up into a retrolenticular hematoma under normal intraocular pressure. The source of bleeding also differs between the two hemorrhagic disorders. In massive expulsive hemorrhage, the bleeding is hypothesized to originate from a short posterior ciliary artery, while in most reported cases of spontaneous subretinal hemorrhage, in most reported cases, the bleeding seemed to originate from a disciform scar.1 Another possible abnormality to be excluded is choroidal or ciliary body melanoma. Approximately 3% of patients with posterior uveal melanoma present with a spontaneous subretinal or intravitreal hemorrhage causing acute or chronic angle-closure glaucoma.18

Ultrasonography helps differentiate a total hemorrhagic choroidal detachment from a choroidal melanoma.19 Computed tomography also provides an accurate means of visualizing the posterior uvea and reveals the nature of any choroidal disease.20 Magnetic resonance imaging may also serve as a diagnostic supplement.6

Medical treatment is reported to be rarely effective.6-11 Most of the previously reported patients underwent enucleation because of intractable pain. Other surgical modalities include retrobulbar alcohol injection, a cyclodestructive procedure, drainage of blood and anterior chamber restoration. However, in an eye with possible melanoma, surgical treatment is inadvisable because it could potentially facilitate tumor extension. If melanoma cannot be excluded entirely on clinical grounds, enucleation remains the most reasonable therapeutic option.8

The visual prognosis is grim because of the disruption of retinal architecture and the markedly elevated intraocular pressure. Prolonged elevated intraocular pressure impairs intraocular blood flow and induces ischemic changes in intraocular structures and phtyhsical changes inevitably follow.6-11

In conclusion, our case suggests that anticoagulant therapy may cause massive subretinal bleeding resulting in secondary angle-closure glaucoma. Therefore, ophthalmologists and physicians (must know about this) should be aware of this potential complication associated with anticoagulant treatment.

Footnotes

None of the authors have financial or proprietary interest in any of the materials mentioned.

References

- 1.Brown GC, Tasman WS, Shields JA. Massive subretinal hemorrhage and anticoagulant therapy. Can J Ophthalmol. 1982;17:227–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosley DH, Schatix IJ, Breneman GM, Keyes JW. Long-term anticoagulant therapy. JAMA. 1963;186:914–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollard JW, Hamilton MJ, Christensen NA, Achor R WP. Problems associated with long-term anticoagulant therapy. Circulation. 1962;25:311–317. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.25.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edward P. Massive choroidal hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration : a complication of anticoagulant therapy. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997;67:223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordan DM, Mead G. Retinal hemorrhage with visual loss during anticoagulant therapy: case report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:99–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb03975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pesin SR, Katz LJ, Augsburger JJ, et al. Acute angle-closure glaucoma from spontaneous massive hemorrhagic retinal or choroidal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:76–84. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parson JH. The pathology of the eye. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York: GP Putnam's Sons; 1906. pp. 1087–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SN, Ho CL, Ho JD, et al. Acute angle-closure glaucoma resulting from spontaneous hemorrhagic retinal detachment in age-related macular degeneration; case reports and literature review. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2001;45:270–275. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(00)00382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood WJ, Smith TR. Senile disciform macular degeneration complicated by massive hemorrhagic retinal detachment and angle-closure glaucoma. Retina. 1983;3:296–303. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198300340-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feman SS, Bartlett RE, Roth AM, Foos RY. Intraocular hemorrhage and blindness associated with systemic anticoagulation. JAMA. 1972;220:1354–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiemann T, Goins K, Smith T, et al. Acute angle closure glaucoma complicating hemorrhagic choroidal detachment associated with parenteral thrombolytic agents. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:752–753. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90722-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozlowski IMD, Hirose T, Jalkh AE. Massive subretinal hemorrhage with acute angle-closure glaucoma in chronic myelocytic leukemia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:832–833. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caronia RM, Sturm RT, Fastenberg DM, et al. Bilateral secondary angle-closure glaucoma as a complication in nonophthalmic patient. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:307–309. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Baba F, Jarrett WH, II, Harbin TS, et al. Massive hemorrhage complicating age related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:1581–1592. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butner RW, McPherson AR. Spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage. Ann Ophthalmol. 1982;14:268–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oyakawa RT, Michels RG, Blasé WP. Vitrectomy for nondiabetic vitreous hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:517–525. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pastror BH, Resnick ME, Rodman T. Serious hemorrhagic complications of anticoagulant therapy. JAMA. 1962;25:311–317. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanoff M. Glaucoma mechanisms in ocular malignant melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;70:898–904. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)92465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu TG, Cano MR, Green RL, et al. Massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage with central retinal apposition. A clinical and echographic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1575–1581. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080110111047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knopp EA, Chymm KY. Spontaneous expulsive choroidal hemorrhage: CT findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:1208–1209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]