Abstract

Background

An understanding of the mechanisms that down-regulate the human anti-pig cellular response is key for xenotransplantation. We have compared the ability of human regulatory T cells (Tregs) to suppress xenogeneic and allogeneic responses in vitro.

Methods

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), CD4+T cells, or CD4+CD25-T cells were stimulated with irradiated human or wild-type (WT) or α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout (GT-KO) pig PBMC in the presence or absence of human CD4+CD25highTregs. In separate experiments, CFSE-labeled human CD4+T cells were stimulated with human or pig PBMC. The expansion and precursor frequencies of alloand xeno-reacitve Tregs were assessed by labeling with FoxP3 mAb and flow cytometric analysis.

Results

The responses of human PBMC, CD4+T cells, and CD4+CD25-T cells to pig PBMC were stronger than to human PBMC (p<0.05). Human anti-GT-KO responses were weaker than anti-WT responses (p<0.05). Human CD4+CD25highTregs suppressed proliferation of CD4+CD25-T cells to both human and pig PBMC stimulator cells with the same efficiency. Allo-reactive CD4+CD25+FoxP3high responder T cells proliferated more than their xeno-reactive counterparts (p<0.05), although xeno-reactive CD4+CD25+T cells proliferated more than allo-reactive cells (p<0.05). There was no difference in precursor frequency between allo- and xeno-reactive CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells.

Conclusions

Human T cell responses to pig cells are stronger than to allogeneic cells. The human response to GT-KO PBMC is weaker than to WT PBMC. Although human Tregs can suppress both responses, expansion of CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells against pig PBMC is weaker than against human PBMC. More human Tregs may be required to suppress the stronger xenogeneic response.

Keywords: Human, Mixed lymphocyte reaction, Pig, Regulatory T cells, Xenotransplantation

INTRODUCTION

While there are several barriers to successful pig-to-human xenotransplantation, the immune responses of the host remain the most important (1). The production of α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout (GT-KO) pigs has reduced the risk of early antibody-mediated rejection related to the presence of anti-Galα1,3Gal (Gal) antibodies in the host (2, 3). More attention now needs to be directed to the potential problems of cellular immunity (4).

Early studies in the mouse suggested a weak xenogeneic response (5, 6), but, in the pig-to-human model, the cellular responses measured in vitro are comparable to, or greater than, the corresponding allogeneic responses (6-8). However, the strength of the cellular response to a xenograft in vivo remains uncertain (4). In particular, there is no definitive report of the human T cell response to GT-KO pig cells.

The cellular immune response to a donor organ is mediated by host T cells that recognize donor allo-antigen. The relative contributions of the direct and indirect pathways in xenotransplantation remain uncertain. Recently, CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been demonstrated to induce a state of T cell hyporesponsiveness, or even unresponsiveness, to an allograft (9, 10). Human Tregs were also found to suppress the xenogeneic response in vitro (11).

In an allogeneic system, the T cell response elicited through the direct pathway is critical in acute rejection, whereas indirect allorecognition predominates later during chronic rejection. By contrast, there is little information on the contribution of direct T cell recognition during the rejection or potential acceptance of xenografts. In the present study, we compared the in vitro behavior of human T cells and Tregs in response to stimulation by allo- and xeno-geneic antigen-presenting cells (APCs) through the direct pathway.

We have investigated the human anti-pig cellular response by the mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR), where T cell and Treg proliferation in response to allo- or pig APCs was assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation or by 5-(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-dilution of proliferating T cells analyzed by flow cytometry.

METHODS

Sources of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from six healthy unrelated human volunteers, with informed consent; blood types were A (n=2), O (n=2), and AB (n=2). PBMC were also obtained from buffy coats from eight human donors (Institute for Transfusion Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA); blood types were A (n=2), B (n=2), O (n=2), and AB (n=2). The volume of each buffy coat was approximately 70-80ml, yielding 500-800×106 PBMC. Therefore, PBMC from a total of 14 human donors were used as responders in MLR to test the allogeneic and xenogeneic (pig) proliferative responses. The stimulator PBMC for the alloresponse were from the same and additional human volunteers with the same blood type as the responder. In allo-combinations, whenever possible responder and stimulator cells were chosen from subjects who hailed from different countries (to try to ensure differences in MHC), but were matched for ABO blood type.

Pig blood was obtained from three wild-type (WT) pigs and three GT-KO pigs (all from Revivicor, Inc., Blacksburg, VA) (2), all of blood group O, and all of a close, but not identical, genetic background (the major difference being the absence of Gal in the GTKO pigs).

Cell Isolations

Human and pig PBMC were isolated by density gradient centrifugation of heparinized whole blood over Ficoll Paque (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The PBMC were washed with RPMI medium twice and the contaminating red cells were lysed with ammonium chloride/potassium solution, when necessary.

Bulk CD4+T cells were isolated from PBMC by negative selection with the CD4+T cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). CD4+T cell purity was >98% by flow cytometric analysis (BD™ LSR II flow cytometer, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). CD4+CD25highT cells and CD4+CD25-T cells were isolated by positive and negative selection from purified (untouched) bulk CD4+T cells using CD25 microbeads (Miltenyi) as previously described (11). By using this approach, CD4+CD25highT cells were isolated from CD4+CD25low/negT cells. The purity of CD4+CD25highT cells and CD4+CD25-T cells was >92% and >98%, respectively. CD4+T cells were used as responders in direct MLR. The CD4+CD25-T cells were used as responders in direct MLR and suppression assays.

3H-thymidine MLR

The MLR was designed to detect responses to autologous, allogeneic, and xenogeneic (WT and GT-KO pig) PBMC. Human bulk PBMC, bulk CD4+T cells, and CD4+CD25-T cells were used as responders. All three responder cells were stimulated with (i) autologous PBMC, (ii) allogeneic human PBMC of the same blood type as the responder cells, (iii) WT pig PBMC, and (iv) GT-KO pig PBMC. For the bulk MLR, 4×105 human PBMC were incubated with an equal number of irradiated (2,500cGy) stimulator cells per well in 96-well round-bottom plates (Corning, Lowell, MA) for 5 days. For the CD4+ direct MLR, 105 CD4+T cells were incubated with 5×105 stimulator cells for 7 days. For the CD4+CD25- direct MLR, 5×104 CD4+T cells were incubated with 2.5×105 stimulator cells for 7 days. All assays were performed in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 1% HEPES buffer, 50U/mL penicillin, and 50μg/mL streptomycin. The optimal conditions for the MLR in our model were determined in preliminary experiments using different stimulator:responder cell ratios and different incubation times.

Each combination of responder-stimulator cells was tested in triplicate. The cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2, and 3H-thymidine (1μCi/well) was added to each well 18h before harvesting. Cells were collected on glass-fiber filter mats with a cell harvester, and were analyzed by β-scintillation counting on a liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The mean result of triplicate cultures was expressed as 3H-thymidine uptake.

Suppression MLR

To assess the ability of isolated CD4+CD25highT cells to suppress the proliferation of allo- or xeno-stimulated CD4+CD25-T cells, 5×104 CD4+CD25-T cells were co-cultured with 2.5×105 irradiated allogeneic or xenogeneic PBMC in 96-well round-bottom plates, and various concentrations of CD4+CD25highT cells were added to the wells (at CD4+CD25highT cells to responder ratios of 1:1, 1:4, 1:16, 1:64 and 1:256). In suppression MLR, responder cells, stimulator cells, and Tregs were incubated together at the same time. The results were harvested after co-culture for 7 days.

CFSE Cell Division Assay

CD4+T cells were labeled with 5μM CFSE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 15min, then washed, recounted, and 1×105 cells were cultured with 2×105 stimulator cells. After 5 days culture, cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4 (PE-Cy7, clone SK3; BD Pharmingen™, San Jose, CA), anti-CD25 (APC-Cy7, clone MA251; BD), and anti-FoxP3 (APC, clone PCH101, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. In some experiments, CFSE-labeled responder cells were stained with PE-IFN-y mAb (clone B27; BD) after restimulating with 5μg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3 (BD) and 1μg/ml soluble anti-CD28 mAb (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 5h.

The harvested CFSE-labeled responder cells were labeled with mAb as described above, and the responder cell proliferation and the precursor frequency was calculated by flow cytometry analysis (12-14) as follows:

where M denotes mitotic events from the experimentally obtained values of the proportion of T cells under each division peak n (Xn) and the total T cell yield (T). Calculation of the total number of mitotic events involved extrapolation of precursor numbers for each division peak. Precursor frequency = total number of reactive precursors / total absolute number of precursors.

Statistical Methods

Values are presented as mean±SEM. The statistical significance of differences was determined by Student’s t test (paired test) or nonparametric tests, as appropriate. The statistical tests were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 4 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences were considered to be significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

1. The human anti-pig MLR response was stronger than the allo-response (in both bulk and direct MLR)

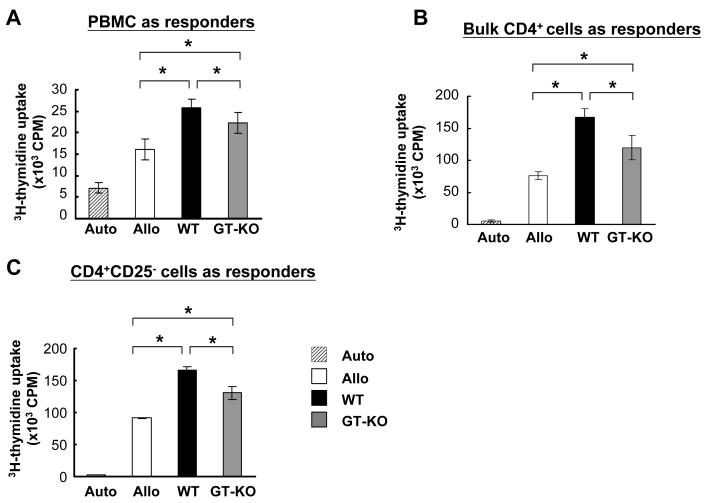

We initially characterized the human anti-allo and anti-pig responses by bulk MLR. After 5 days of culture in bulk MLR, both the anti-WT and anti-GT-KO responses were stronger compared to the anti-allo response (p<0.05) (Figure 1A). In direct MLR using bulk CD4+T cells, the anti-pig responses were also stronger than the anti-allo response (p<0.05) (Figure 1B). In addition, when CD4+CD25-T cells were stimulated by allo or pig PBMC, the anti-pig responses were again stronger than the allo-response (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Human anti-allo and anti-pig MLR. Three types of responder cells were tested — bulk PBMC (A), bulk CD4+ (B and D), and CD4+CD25- (C). The human anti-pig response was consistently stronger than the allo-response (p<0.05), and the human anti-GT-KO pig response was consistently weaker than the anti-WT pig response (p<0.05).

(A) Bulk MLR: human bulk PBMC were used as responder cells and stimulated by irradiated auto, allo, WT, and GT-KO PBMC (n=8).

(B) Human bulk CD4+T cells were used as responder cells to test the direct pathway of human xenogeneic MLR (n=8).

(C) Human CD4+CD25-T cells were used as responder cells and stimulated by irradiated auto, allo, WT, and GT-KO PBMC (n=8).

(Auto = autologous response; Allo = allogeneic response; WT = human anti-WT pig response; GT-KO = human anti-GT-KO pig response.)

2. The human MLR response was weaker to GT-KO than to WT pig PBMCs

There have been no reports comparing the human anti-WT and anti-GT-KO pig responses. In bulk MLR, and bulk CD4+ or CD4+CD25-T cells in direct MLR, the human anti-GT-KO response was weaker than the anti-WT response (p<0.05) (Figures 1A-C).

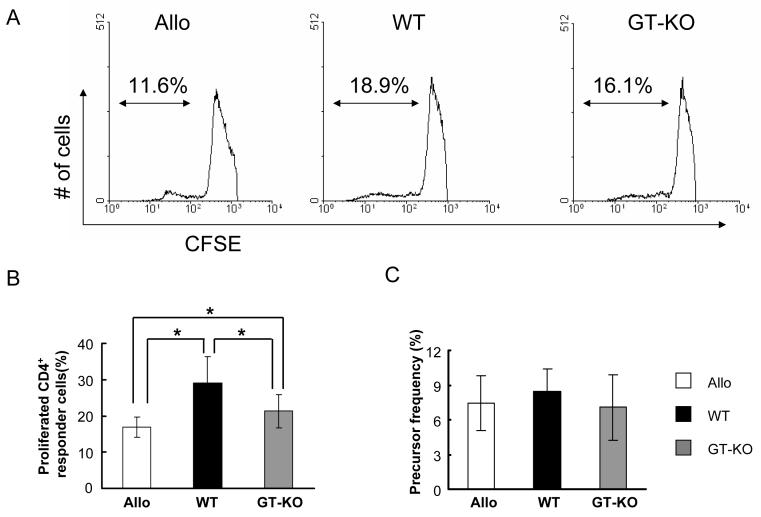

3. The strength of the human anti-pig response correlated with greater proliferation of human pig-reactive CD4+T cells

We speculated that the strength of the anti-pig response was related to the presence of more anti-pig precursor T cells in human blood or more extensive proliferation of xeno-reactive T cells than of allo-reactive T cells. To study the proliferation of human xeno-reactive T cells in direct MLR, CFSE MLR was carried out by staining bulk CD4+T responder cells with CFSE. The numbers of proliferating WT-reactive and GT-KO-reactive CD4+T cells were greater than of allo-reactive CD4+T cells (Figures 2A and B). The mean percentage of proliferating allo-reactive CD4+T cells was 17%, which was significantly lower than that of proliferating WT-reactive or GT-KO-reactive CD4+T cells (29% and 21%, respectively; p<0.05) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Proliferation of allo-, WT-, and GT-KO-reactive CD4+T cells in CFSE MLR. Human bulk CD4+T responder cells were stained with CFSE and stimulated by allo, WT, or GT-KO PBMC in MLR. The responder cells were harvested after 5 days culture, and proliferating CD4+ responder cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

(A) Percentages of proliferating allo-, WT-, and GT-KO-reactive CD4+ responder cells (Representative data of 6 experiments).

(B) Cumulative results of percentage of proliferating allo-, WT-, and GT-KO-reactive CD4+ responder cells (n=6). The “y” axis represents the percentage of proliferated CD4+ responder cells (*p<0.05).

(C) Precursor frequency of allo-, WT-, and GT-KO-reactive CD4+ responder cells (n=6). The “y” axis represents the percentage of allo-, WT-, or GT-KO-reactive CD4+ precursors in the responder cell population.

4. Precursor frequency was the same for pig-reactive and allo-reactive CD4+T cells

The precursor frequency of CD4+T cells was determined under the stimulation of allo- or xeno-PBMC by using CFSE MLR. Although pig-reactive CD4+T cells proliferated more extensively than allo-reactive CD4+T cells, the precursor frequency of xeno-reactive CD4+T cells was not different from that of allo-reactive CD4+T cells (Figure 2C).

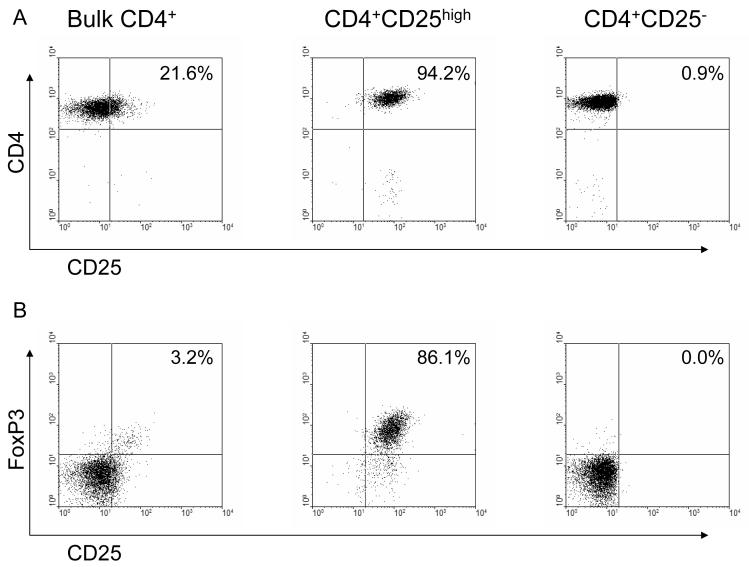

5. Human CD4+CD25highT cells were isolated from PBMC with high purity and with the characteristics of Treg

It is accepted that Tregs can control the T cell immune response (15-20). Although the more efficient expansion of pig-reactive CD4+T cells (Figure 2B) might be sufficient to account for the observation that the human anti-pig response was greater than the allo-response, it was also possible that human Tregs might respond differently to allo or xeno-stimulation. We first isolated the human CD4+CD25highT cells from PBMC (Figure 3A), and tested whether the isolated human CD4+CD25highT cells possessed the characteristics of Tregs. High purity human CD4+CD25highT cells were isolated from bulk CD4+T cells by anti-CD25 microbeads (Figure 3A). More than 80% of the isolated CD4+CD25highT cells exhibited high expression of the Treg marker FoxP3 (representing naturally-occuring Treg, Figure 3B) whereas purified CD4+CD25-T cells were FoxP3-negative. When isolated CD4+CD25highT cells were stimulated with PBMC, neither allo nor pig PBMC was able to induce proliferation of these cells (Figure 4A). Failure of proliferation under T cell receptor stimulation is one of the main features of Tregs in in vitro studies (21).

Figure 3.

Expression of CD25 and FoxP3 in human bulk CD4+ (left), CD4+CD25high (middle), and CD4+CD25- (right) T cells. Human bulk CD4+, CD4+CD25high, and CD4+CD25- T cells were stained for expression of CD4 and CD25 (A) and intracellular expression of FoxP3 (B). Results of one representative experiment are shown.

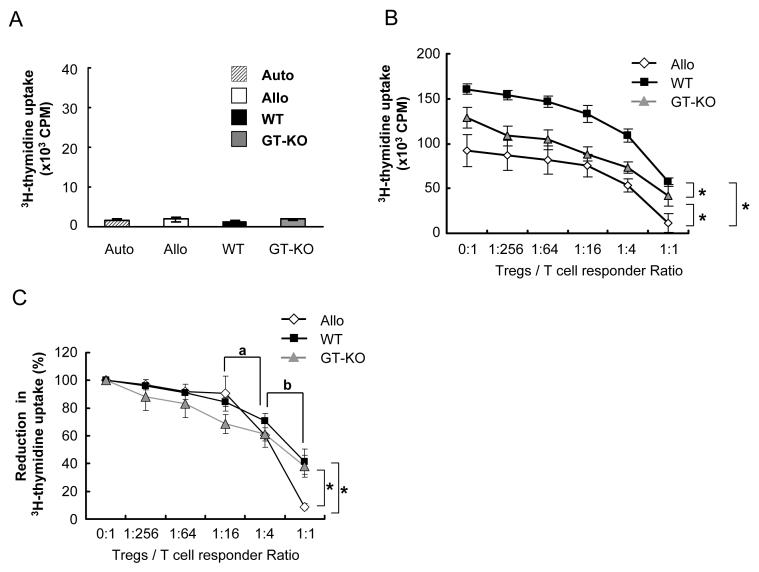

Figure 4.

The suppressive function of human Tregs on allogeneic or xenogeneic MLR.

(A) Anergic state of human CD4+CD25highT cells under allogeneic or xenogeneic PBMC stimulation. Human CD4+CD25highT cells were isolated from human PBMC, and were stimulated by irradiated autologous, allo, WT, or GT-KO PBMC for 7 days (n=7).

(B) Suppressive function of isolated human CD4+CD25highT cells on MLR is demonstrated by 3H-thymidine uptake. Human CD4+CD25-T cells were used as responder cells and stimulated by allo, WT, or GT-KO PBMC, and co-cultured with different numbers of human CD4+CD25highT cells (n=7). The suppressive effect on allogeneic antigen-presenting cells was greater than on pig cells (*p<0.05). (For suppression MLR, responder cells, stimulator cells, and CD4+CD25highT cells were incubated at the same time.)

(C) The suppressive function of human CD4+CD25highT cells on human anti-allo or anti-pig responses is demonstrated by reduction in 3H-thymidine uptake, which was converted from (B) by resetting the 0:1 CD4+CD25highT cell:responder ratio to 100%. “a” indicates that the percentage inhibition at a ratio of 1:4 was significantly greater than at a ratio of 1:16 for allo, WT, and GT-KO reactions (n=7, p<0.05). “b” indicates that the percentage of suppression at a ratio of 1:1 was significantly greater than at a ratio of 1:4 for allo, WT, and GT-KO responses (n=7, p<0.05). “*” indicates that the reduction in 3H-thymidine uptake of the allo-response was significantly greater than the WT- and GT-KO-reactive responses (n=7, p<0.05).

6. Human Tregs suppressed both the allo- and xeno-responses, and in high concentration suppressed the allo-response more efficiently

We established suppression MLR using CD4+CD25-T cells as responder cells, with the addition of different numbers of CD4+CD25highT cells to test the efficiency of suppression. Human CD4+CD25highT cells suppressed both the allo- and xeno-responses (Figure 4B). When the number of CD4+CD25highT cells was increased, the MLR responses were suppressed in a dose-dependent fashion with the same efficiency (Figure 4B). Allo, WT, and GT-KO suppression MLR revealed statistically different 3H-thymidine uptakes. However, since the count for 3H-thymidine uptake for allo, WT, and GT-KO responses differed (as evidenced in Figure 1C), we cannot directly compare the efficiency of suppression by CD4+CD25highT cells in these three groups. We determined the reduction in 3H thymidine uptake for allo, WT, and GT-KO responses by adjusting the 3H thymidine uptake in each case to an identical start point of 100% (in the absence of CD4+CD25highT cells). Again, human CD4+CD25highT cells suppressed all responses in a dose-dependent pattern (Figure 4C). A ratio of 1:16 of CD4+CD25highT cells to responders significantly suppressed the responses. As the concentration of CD4+CD25highT cells became greater, the curve of reduction in 3H-thymidine uptake became steeper.

At each ratio of CD4+CD25highT cells to responder cells, the anti-pig response was stronger than the allo-response, and the anti-WT response was stronger than the anti-GT-KO response (Figure 4B). These results were consistent with those of the xenogeneic MLR (Figure 1). However, when the results of the 3H-thymidine uptake suppression MLR were converted into reduction in 3H-thymidine uptake, a significant difference in suppression by CD4+CD25highT cells was observed only at a ratio of 1:1, and a more efficient suppression of the allo-response than of the xeno-response was demonstrated; the allo response was limited to 8.8%, whereas the WT and GT-KO responses remained at 41% and 38%, respectively (Figure 4C).

7. The percentage of proliferated allo-reactive CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells was higher than that of xeno-reactive CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells, but the precursor frequency remained the same

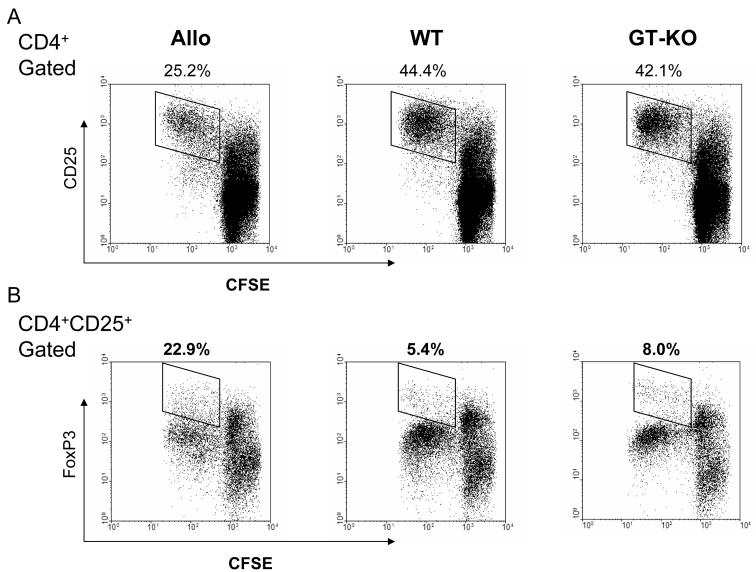

Since human CD4+CD25+T cells suppressed the allo-response more efficiently than the xeno-response, we studied how CD4+CD25+T cells proliferated in response to allo- or xeno-stimulation. We established CFSE MLR by using CFSE-stained bulk CD4+T cells as responder cells stimulated by allo or pig PBMC. The cells were then harvested and stained with monoclonal antibodies for CD4, CD25, FoxP3, and IFN-γ.

Human CD4+T cells proliferated more extensively in response to pig stimulators than to allo-stimulators, as evidenced by higher expression of CD25+ in proliferating cells (Figure 5A). This result was consistent with those of 3H-thymidine uptake (Figure 1). However, greater proliferation of CD25+T cells did not correlate with greater proliferation of FoxP3+ cells. The percentage of CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cell proliferation was determined by calculating the ratio of the proliferated fraction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells to the proliferated fraction of CD25+T cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Proliferation of allo-, WT-, and GT-KO-reactive human Tregs in CFSE MLR. Human bulk CD4+T cells, stained with CFSE, were used as responder cells and stimulated by irradiated allo, WT, or GT-KO PBMC for 5 days. The responder cells were then harvested and stained for CD4, CD25, and FoxP3, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

(A) Responder cells were gated on the CD4+ population, and proliferation of the CD25+ fraction was detected (indicated). The fractions of proliferating allo-reactive, WT-reactive, and GT-KO-reactive CD25+ responder cells are indicated in the upper left, upper middle, and upper right figures, respectively.

(B) The responder cells were gated on the CD4+CD25+ population, and analyzed for their expression of FoxP3. The fractions of proliferating CD25+FoxP3+ cells in the responder cell populations are indicated. The percentage denotes the percentage of proliferating CD25+ cells that are CD25+FoxP3high cells (representative data from 8 experiments).

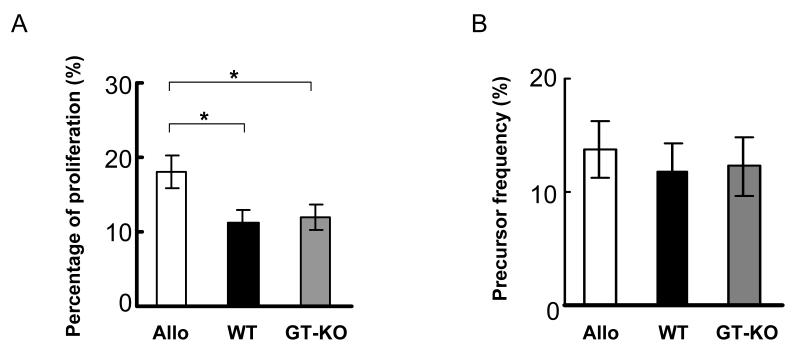

The percentage of proliferated allo-reactive CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells was statistically greater than that of xeno-reactive CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells, with 18% of proliferated CD25+T cells being allo-reactive FoxP3high T cells, while WT- and GT-KO-reactive FoxP3high T cells constituted only 11% (p<0.05) (Figure 6A). Although allo-reactive FoxP3high T cells proliferated more extensively, they did not demonstrate higher precursor frequency compared with those of xeno-reactive CD4+CD25+FoxP3high cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

The percentage of proliferating allo-reactive human CD25+FoxP3high cells was higher than that of either WT- or GT-KO-reactive human CD25+FoxP3high cells, but the precursor frequency of allo-reactive human CD25+FoxP3high cells was not different.

(A) Human bulk CD4+T cells were stimulated by allo, WT, or GT-KO PBMC, and the percentage of proliferating CD25+FoxP3+ cells was calculated (n=8, *p<0.05).

(B) The precursor frequencies of allo-, WT-, and GT-KO-reactive human CD25+FoxP3high cells were calculated from the CFSE MLR (cumulative results from 8 experiments).

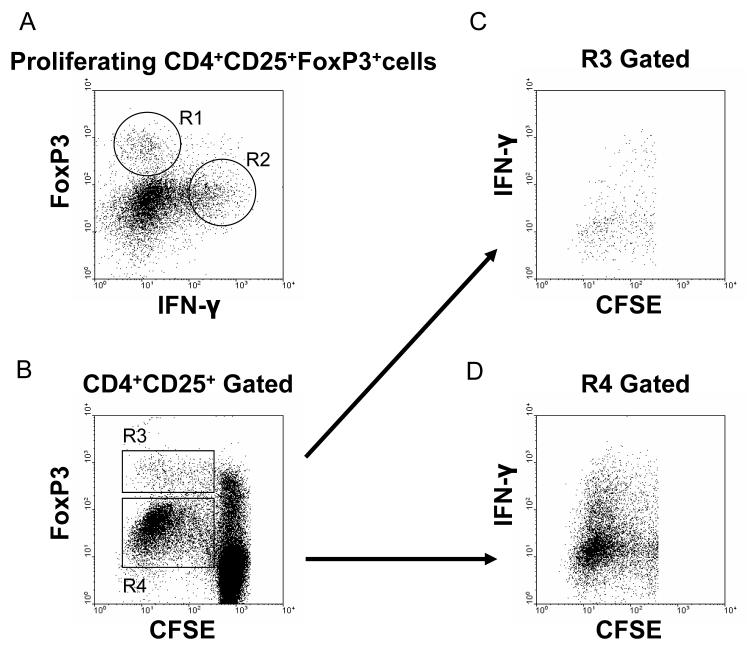

8. FoxP3 was up-regulated in stimulated CD4+T cells

FoxP3 expression is considered necessary and sufficient for Tregs development and function in murine models (20, 22). However, its specificity in humans remains controversial because induction of FoxP3 in activated T cells may occur without suppressive activity (23-25). In the present experiments, FoxP3 expression was distributed into two populations, FoxP3low and FoxP3high (Figure 5B). For the following reasons, only the FoxP3high population was considered to be true Tregs. First (as shown in Figure 5B), proliferated CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells in the allo, WT, or GT-KO groups showed both FoxP3low and FoxP3high cells, with more FoxP3low than FoxP3high cells. If both the FoxP3low and FoxP3high cells were considered to be Tregs, more than 96% of CD4+CD25+T cells would be composed of FoxP3+ cells. Such a high percentage of Tregs in CD4+CD25+T cells has never been reported. In addition, there were no FoxP3- cells in the proliferated population after stimulation (Figure 5B). Second, when stained with anti-IFN-γ, two groups of stimulated CD4+ responder cells were observed, i.e., FoxP3high/IFN-ylow and FoxP3low/IFN-yhigh (Figure 7). Most FoxP3low cells showed high expression of IFN-y, which is a marker for effector cells rather than for regulatory cells (26, 27) (Figures 7B-D).

Figure 7.

FoxP3high cells in proliferated CD4+T responder cells were considered to be regulatory T cells. Human bulk CD4+T cells, stained with CFSE, were co-cultured with allo, WT, or GT-KO PBMC for 5 days, harvested, and stained for CD4, CD25, FoxP3, and IFN-y.

(A) Two populations of FoxP3+ cells were identified in the CD4+CD25+ population of responder cells. The proliferating responder cells were gated on CD4+CD25+FoxP3+. FoxP3high cells (R1) expressed a low level of IFN-y, yet FoxP3low cells (R2) had high expression of IFN-y.

(B) Two subpopulations of FoxP3+ cells were identified in the proliferating responder population (R3 = FoxP3high; R4 = FoxP3low).

(C) FoxP3high cells (R3) expressed a low level of IFN-γ.

(D) FoxP3low cells (R4) expressed a high level of IFN-γ, suggesting them to be effector cells.

Data are from one experiment representative of three performed.

DISCUSSION

Pig-to-human transplantation offers a potentially unlimited source of donor organs. Since the production of GT-KO pigs, hyperacute rejection has been largely prevented (28). Cell-mediated rejection, previously obscured by hyperacute rejection, is incompletely understood, and its control will be necessary (29).

Although not all reports agree (30, 31), the anti-pig response is believed to be stronger than the allo-response (7, 32-34). SLA class II has been reported to be the key determinant in the stimulation of human T cells (32, 35-37), but the mechanism by which human T cells proliferate more extensively in response to porcine stimulation has not been delineated. Little is known about the relative importance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in human anti-pig immunity (30).

T cells are essential for both acute and chronic graft rejection. Xenogeneic graft recognition can be direct and/or indirect (36, 38). Activated pig endothelial cells have been reported to directly stimulate highly-purified human CD4+T lymphocytes by a SLA class II-restricted, direct presentation pathway (35, 39-41).

In the present study, the human anti-pig response was determined to be consistently and significantly stronger than the allo-response in both the bulk and direct MLR. We report for the first time that the human anti-GT-KO pig response is weaker than the human anti-WT response, even though these two types of pig were of close (but not identical) genetic background. The level of SLA class II expression in WT and GT-KO PBMC was found to be the same (data not shown). We did not investigate why the human T cell proliferative response to these two types of pig cells differed. One possible explanation is that antigenicity was reduced by the absence of Gal antigens in GT-KO pigs, resulting in a reduction in the strength of the memory response of pig-specific T cells. Naturally-occurring xeno-specific memory T cells have been detected in humans (42). . In support of the role of Gal is the work of Li et al (43), who demonstrated that the human T cell response to PAEC stimulators decreased when Gal was removed from the PAEC. It has also been demonstrated that the human cytokine response to WT pig cells is greater than to allo cells and to GT-KO pig cells (44, 45).

A second possible explanation, however, is that the human T cell response differed because the WT and GTKO pigs might have expressed slightly different SLA class II antigens (even though the level of expression of SLA class II was not measurably different). However, the T cell responses of all the humans tested against all three of the GTKO pigs were consistently less than to the three WT pigs, suggesting that the absence of Gal was a major factor in the reduced response.

We speculate that the T cell responses stimulated by allo- or pig cells are the summation of pro-proliferation and anti-proliferation factors. A higher precursor frequency or a stronger proliferative capacity of antigen-specific T cells would collectively result in greater proliferation. A high percentage of antigen-specific T cells (i.e., actual responders) in the lymphocyte pool (i.e., all potential responders) and an increased “strength” of the proliferative response (i.e., the frequency of division of each responding T cell) both contribute to the proliferation of an antigen-specific response (46). In contrast, natural Tregs, that suppress antigen-specific proliferation, have a negative influence.

The precursor frequency of T cells with receptors that recognize allo-antigen through the direct pathway has been reported to be between 1-10% (47). In the present study, we utilized CFSE-MLR in combination with flow cytometric analysis (47-49), which has been demonstrated to be a useful tool to study lymphocyte division kinetics and differentiation in a variety of in vitro and in vivo systems (12, 46). Previous studies have compared allo-and xeno-reactive human T cell precursor frequencies by means of the limiting dilution assay (LDA), a technique based on the statistical probability that T cells cultured individually develop effector function. However, the LDA only provides information on the number of cytotoxic T cell precursors, and the results can be highly variable (39, 44, 50). Unlike the LDA, CFSE-MLRs provide information on T cell proliferation (through CFSE-dilution) and also on the surface and intra-cellular phenotypes of T cells (i.e., CD25, FoxP3, cytokines). We detected the precursor frequency of human CD4+T cells to allo-stimulators to be no higher than that of pig-reactive CD4+T cells. It is surprising that T cells recognize alloantigens with the same frequency as SLA class II antigens because allogeneic HLA molecules are more like self than SLA class II molecules (51). The large size of the human T cell receptor repertoire may explain why the precursor frequencies of human T cells that recognize SLA and allogeneic HLA are similar. However, pig-reactive CD4+T cells proliferated more than allo-reactive CD4+T cells, a result consistent with those of the 3H-thymidine experiments.

A growing body of evidence indicates that CD4+CD25+Tregs maintain transplantation tolerance in addition to peripheral tolerance to self-antigens (38, 52-57). Given the fact that Tregs have a diverse T cell receptor repertoire, it is reasonable to anticipate that they are capable of cross-reactivity on both allo- and pig antigens (38, 58, 59), similar to other T cells (9). Our findings and those of others (7, 32, 34) indicate that human T cells can proliferate in response to pig cells, suggesting that human Tregs may also react to pig antigens.

Human Tregs of CD25highFoxP3+ phenotype are defined by their anergic state when stimulated through the T cell receptor, and by their ability to suppress the proliferation of CD25-T cells. In the present study, the isolated naturally-occurring human Tregs fulfilled these criteria (26, 55, 58-60).

Human Tregs suppress anti-pig responses in addition to the allo-response (11), a finding we confirmed by suppression MLR. Suppression of the allo, WT, and GTKO responses was dose-dependent, and our data suggest that the efficiency of suppression of these three responses was similar (Figure 4). However, more Tregs are likely to be required to suppress the xeno-responses because these are stronger than the allo-response. We have not investigated other Treg:T effector cell ratios. However, it is very likely that increasing numbers of Tregs would exert a more suppressive effect on the T cell xenoresponse, as occurs in the T cell alloresponse.

Human CD4+T cells proliferated more extensively in response to pig than allo stimulation but, even though the precursor frequency of pig- and allo-reactive Tregs was equivalent, pig-reactive Tregs demonstrated a weaker proliferative capacity compared with allo-reactive Tregs. More Tregs were required to control the xeno-response to the same extent as the allo-response.

We also investigated human T cell and Treg allo responses in the presence of ABO-incompatibility. We did not find significant differences between the T cell and Treg responses to human ABO-compatible and incompatible APCs (not shown). Taken together, these findings suggest that the differences in human T cell response seen in our model were mainly dependent on the levels of HLA disparity between responder and stimulator cells.

Positive intracellular staining of FoxP3 is considered an important marker for human Tregs (61). In the current studies, although two populations of proliferating FoxP3+ cells were identified, only FoxP3high cells were considered to be Tregs. FoxP3low cells were regarded as effector cells. To our knowledge, different levels of FoxP3 expression in activated human CD4+T cells stimulated by allo or pig antigens have not been reported previously. A limitation of our study is that we did not isolate the FoxP3high cells for further functional suppressor assays to prove their suppressive capacity, but we did demonstrate that FoxP3high cells expressed low levels of IFN-y. INF-y production is considered an essential function of effector cells, and Tregs are recognized for their ability to suppress the production of INF-y by effector cells (24, 26, 27). Functional studies of allo- or pig-reactive Tregs have been hampered by a lack of suitable cell-surface markers that specifically enable their purification (62). CD127 may prove to be a biomarker for human Tregs (63, 64), and may facilitate the purification of allo- or pig-reactive Tregs.

Recent studies demonstrating that FoxP3 expression in human Tregs does not precisely correlate with suppressive function partially support our finding of different levels of FoxP3 expression in activated human CD4+T cells (20, 65, 66). The suppressive function of T cells with attenuated expression of FoxP3 is compromised (67). The effects of FoxP3 may, therefore, represent a continuum rather than a binary on-off switch (68), and a sustained high level of FoxP3 expression may be required for Tregs phenotype and function in humans (66). FoxP3 may be behaving like an activation-induced gene in human CD4+ cells (20). Further study to test whether FoxP3high and FoxP3low cells possess the regulatory phenotype is required.

In conclusion, we have confirmed that the human anti-pig cellular response is significantly stronger than the allo-response. Since we found the human anti-GT-KO pig response to be weaker that the anti-WT response, the GT-KO pig should provide an advantage in respect of both humoral and cellular immunities as a xenograft donor. Although in vivo large animal studies will be needed to confirm the human Treg effect in organ xenotransplantation, our in vitro studies suggest that, although naturally-occurring human Tregs suppress T cell proliferation induced by both allo and pig antigens with the same efficiency, more Tregs might be needed to suppress the stronger xeno-response than the allo-response. Both CD4+T cells and Tregs individually have the same precursor frequencies in the recognition of allo and pig antigens, but CD4+T cells have a greater proliferative capacity to pig antigens than to allo-antigens, whereas Tregs proliferate more in the allo-response than the xeno-response.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Yih Jyh Lin, M.D., was supported by the National Cheng Kung University, Tainan City, Taiwan. Hidetaka Hara, M.D., Ph.D. and Daisuke Tokita, M.D., Ph.D. are recipients of a grant from the Uehara Memorial Foundation, Japan. Research in our laboratory is funded in part by NIH Grant U01-AI068642 (DKCC) and by a Sponsored Research Agreement between Revivicor, Inc. and the University of Pittsburgh.

ABBREVIATIONS

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CFSE

5-(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- Gal

Galα1,3Gal

- GT-KO

α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout

- LDA

limiting dilution assay

- MLR

mixed lymphocyte reaction

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- WT

wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper DK. Clinical xenotransplantion--how close are we? Lancet. 2003;362(9383):557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phelps CJ, Koike C, Vaught TD, et al. Production of alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science. 2003;299(5605):411. doi: 10.1126/science.1078942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolber-Simonds D, Lai L, Watt SR, et al. Production of alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase null pigs by means of nuclear transfer with fibroblasts bearing loss of heterozygosity mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(19):7335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307819101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buhler LH, Cooper DK. How strong is the T cell response in the pig-to-primate model? Xenotransplantation. 2005;12(2):85. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2004.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auchincloss H., Jr Cell-mediated xenoresponses: strong or weak? Clin Transplant. 1994;8(2 Pt 2):155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auchincloss H, Jr., Sachs DH. Xenogeneic transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada K, Sachs DH, DerSimonian H. Human anti-porcine xenogeneic T cell response. Evidence for allelic specificity of mixed leukocyte reaction and for both direct and indirect pathways of recognition. J Immunol. 1995;155(11):5249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platt JL. Immunobiology of xenotransplantation. Transpl Int. 2000;13(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1007/s001470050265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood KJ, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(3):199. doi: 10.1038/nri1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldmann H, Graca L, Cobbold S, Adams E, Tone M, Tone Y. Regulatory T cells and organ transplantation. Semin Immunol. 2004;16(2):119. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter CM, Bloom ET. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress anti-porcine xenogeneic responses. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(8):2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells AD, Gudmundsdottir H, Turka LA. Following the fate of individual T cells throughout activation and clonal expansion. Signals from T cell receptor and CD28 differentially regulate the induction and duration of a proliferative response. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(12):3173. doi: 10.1172/JCI119873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nitta Y, Nelson K, Andrews RG, Thomas R, Gaur LK, Allen MD. CFSE dye dilution mixed lymphocyte reactions quantify donor-specific alloreactive precursors in non-human primate cardiac graft rejection. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(12):326. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokita D, Ohdan H, Onoe T, Hara H, Tanaka Y, Asahara T. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells contribute to alloreactive T-cell tolerance induced by portal venous injection of donor splenocytes. Transpl Int. 2005;18(2):237. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2004.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shevach EM, McHugh RS, Piccirillo CA, Thornton AM. Control of T-cell activation by CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:58. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckner JH, Ziegler SF. Regulating the immune system: the induction of regulatory T cells in the periphery. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(5):215. doi: 10.1186/ar1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang S, Lechler RI, He XS, Huang JF. Regulatory T cells and transplantation tolerance. Hum Immunol. 2006;67(10):765. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aluvihare VR, Betz AG. The role of regulatory T cells in alloantigen tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:330. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franzke A, Hunger JK, Dittmar KE, Ganser A, Buer J. Regulatory T-cells in the control of immunological diseases. Ann Hematol. 2006;85(11):747. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziegler SF. FOXP3: of mice and men. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baecher-Allan C, Brown JA, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1245. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):20. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, et al. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25- T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(9):1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan ME, van Bilsen JH, Bakker AM, et al. Expression of FOXP3 mRNA is not confined to CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells in humans. Hum Immunol. 2005;66(1):13. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allan SE, Passerini L, Bacchetta R, et al. The role of 2 FOXP3 isoforms in the generation of human CD4+ Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(11):3276. doi: 10.1172/JCI24685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longhi MS, Hussain MJ, Mitry RR, et al. Functional study of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in health and autoimmune hepatitis. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):4484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Jones KL, Woollard DJ, et al. Defining target antigens for CD25+ FOXP3 + IFN-gamma- regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85(3):197. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tseng YL, Kuwaki K, Dor FJ, et al. alpha1,3-Galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pig heart transplantation in baboons with survival approaching 6 months. Transplantation. 2005;80(10):1493. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000181397.41143.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorling A. Clinical xenotransplantation: pigs might fly? Am J Transplant. 2002;2(8):695. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirk AD, Li RA, Kinch MS, Abernethy KA, Doyle C, Bollinger RR. The human antiporcine cellular repertoire. In vitro studies of acquired and innate cellular responsiveness. Transplantation. 1993;55(4):924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T, Li YP, Yang ZM. [Direct and indirect recognition in pig-to-man xenotransplantation] Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1999;13(6):373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorling A, Lombardi G, Binns R, Lechler RI. Detection of primary direct and indirect human anti-porcine T cell responses using a porcine dendritic cell population. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(6):1378. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorling A, Lechler RI. T cell-mediated xenograft rejection: specific tolerance is probably required for long term xenograft survival. Xenotransplantation. 1998;5(4):234. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.1998.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonenfant C, Vallee I, Sun J, et al. Analysis of human CD4 T lymphocyte proliferation induced by porcine lymphoblastoid B cell lines. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10(2):107. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bravery CA, Batten P, Yacoub MH, Rose ML. Direct recognition of SLA- and HLA-like class II antigens on porcine endothelium by human T cells results in T cell activation and release of interleukin-2. Transplantation. 1995;60(9):1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dorling A, Binns R, Lechler RI. Significant primary indirect human T-cell anti-pig xenoresponses observed using immature porcine dendritic cells and SLA-class II-negative endothelial cells. Transplant Proc. 1996;28(2):654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vallee I, Guillaumin JM, Thibault G, et al. Human T lymphocyte proliferative response to resting porcine endothelial cells results from an HLA-restricted, IL-10-sensitive, indirect presentation pathway but also depends on endothelialspecific costimulatory factors. J Immunol. 1998;161(4):1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang S, Herrera O, Lechler RI. New spectrum of allorecognition pathways: implications for graft rejection and transplantation tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(5):550. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray AG, Khodadoust MM, Pober JS, Bothwell AL. Porcine aortic endothelial cells activate human T cells: direct presentation of MHC antigens and costimulation by ligands for human CD2 and CD28. Immunity. 1994;1(1):57. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rollins SA, Kennedy SP, Chodera AJ, Elliott EA, Zavoico GB, Matis LA. Evidence that activation of human T cells by porcine endothelium involves direct recognition of porcine SLA and costimulation by porcine ligands for LFA-1 and CD2. Transplantation. 1994;57(12):1709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charreau B, Coupel S, Boulday G, Soulillou JP. Cyclosporine inhibits class II major histocompatibility antigen presentation by xenogeneic endothelial cells to human T lymphocytes by altering expression of the class II transcriptional activator gene. Transplantation. 2000;70(2):354. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200007270-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartig CV, Haller GW, Sachs DH, Kuhlenschmidt S, Heeger PS. Naturally developing memory T cell xenoreactivity to swine antigens in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164(5):2790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Li T, Bu H, Cheng J, Chen Y, Yang Z. Xenoantigenacity of Chinese Neijiang pig-related to xenotransplantation. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(5):875. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu XC, Goodman J, Sasaki H, Lowell J, Mohanakumar T. Activation of natural killer cells and macrophages by porcine endothelial cells augments specific T-cell xenoresponse. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(4):314. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saethre M, Schneider MK, Lambris JD, et al. Cytokine secretion depends on Galalpha(1,3)Gal expression in a pig-to-human whole blood model. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gudmundsdottir H, Wells AD, Turka LA. Dynamics and requirements of T cell clonal expansion in vivo at the single-cell level: effector function is linked to proliferative capacity. J Immunol. 1999;162(9):5212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suchin EJ, Langmuir PB, Palmer E, Sayegh MH, Wells AD, Turka LA. Quantifying the frequency of alloreactive T cells in vivo: new answers to an old question. J Immunol. 2001;166(2):973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyons AB. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243(12):147. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tokita D, Shishida M, Ohdan H, et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells that endocytose allogeneic cells suppress T cells with indirect allospecificity. J Immunol. 2006;177(6):3615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunningham AC, Butler TJ, Kirby JA. Demonstration of direct xenorecognition of porcine cells by human cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunology. 1994;81(2):268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alam SM, Travers PJ, Wung JL, et al. T-cell-receptor affinity and thymocyte positive selection. Nature. 1996;381(6583):616. doi: 10.1038/381616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor PA, Noelle RJ, Blazar BR. CD4(+)CD25(+) immune regulatory cells are required for induction of tolerance to alloantigen via costimulatory blockade. J Exp Med. 2001;193(11):1311. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gregori S, Casorati M, Amuchastegui S, Smiroldo S, Davalli AM, Adorini L. Regulatory T cells induced by 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and mycophenolate mofetil treatment mediate transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;167(4):1945. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Weber M, Domenig C, Strom TB, Zheng XX. Tracking the immunoregulatory mechanisms active during allograft tolerance. J Immunol. 2002;168(5):2274. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Graca L, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. Identification of regulatory T cells in tolerated allografts. J Exp Med. 2002;195(12):1641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng XX, Sanchez-Fueyo A, Sho M, Domenig C, Sayegh MH, Strom TB. Favorably tipping the balance between cytopathic and regulatory T cells to create transplantation tolerance. Immunity. 2003;19(4):503. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ochando JC, Homma C, Yang Y, et al. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(6):652. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hara M, Kingsley CI, Niimi M, et al. IL-10 is required for regulatory T cells to mediate tolerance to alloantigens in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):3789. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quezada SA, Fuller B, Jarvinen LZ, et al. Mechanisms of donor-specific transfusion tolerance: preemptive induction of clonal T-cell exhaustion via indirect presentation. Blood. 2003;102(5):1920. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(6):389. doi: 10.1038/nri821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. A well adapted regulatory contrivance: regulatory T cell development and the forkhead family transcription factor Foxp3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(4):331. doi: 10.1038/ni1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Banham AH. Cell-surface IL-7 receptor expression facilitates the purification of FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(12):541. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203(7):1701. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203(7):1693. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bacchetta R, Passerini L, Gambineri E, et al. Defective regulatory and effector T cell functions in patients with FOXP3 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI25112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gavin MA, Torgerson TR, Houston E, et al. Single-cell analysis of normal and FOXP3-mutant human T cells: FOXP3 expression without regulatory T cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(17):6659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509484103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Regulatory T-cell functions are subverted and converted owing to attenuated Foxp3 expression. Nature. 2007;445(7129):766. doi: 10.1038/nature05479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Curiel TJ. Regulatory T-cell development: is Foxp3 the decider? Nat Med. 2007;13(3):250. doi: 10.1038/nm0307-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]