Abstract

To report the association of a unilateral serous macular detachment with severe postoperative pain. A 71-year-old woman presented with a sudden decrease in vision in the right eye, seven days after a total knee replacement arthroplasty. The patient's history was unremarkable except for a severe pain greater than the visual analog scale of 8 points for about 2 days after surgery. Retinal examination showed a well differentiated serous detachment that was about 3.5 disc diameter in size and located in the macular area. Fluorecein angiography and indocyanine green angiography showed delayed perfusion of the choriocapillaris without leakage points in the early phase and persistent hypofluorescence with pooling of dye in the subretinal space in the late phase. There was a spontaneous resolution of the serous detachment and the choroidal changes with residual pigment epithelial changes. Severe postoperative pain may influence the sympathetic activity and introduce an ischemic injury with a focal, choroidal vascular compromise and secondary dysfunction of overlying RPE cells in select patients.

Keywords: Choroidal ischemia, Pain, Serous retinal detachment, Total knee replacement arthroplasty

Serous retinal detachment secondary to choroidal ischemia have been reported in very few cases in the literature but is a well-documented cause of visual loss in preeclampsia or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).1,2 We report the case of a 71-year-old woman who developed unilateral choroidal ischemia with serous retinal detachment associated with severe pain following total knee replacement arthroplasty (TKRA). There were spontaneous resolutions of the serous detachment and the choroidal changes with residual pigment epithelial changes. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing serous macular detachment following severe postoperative pain.

Case Report

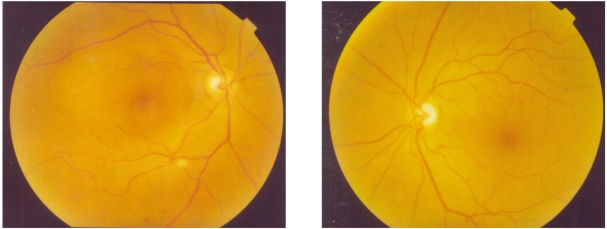

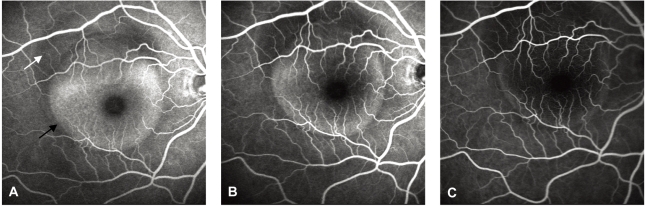

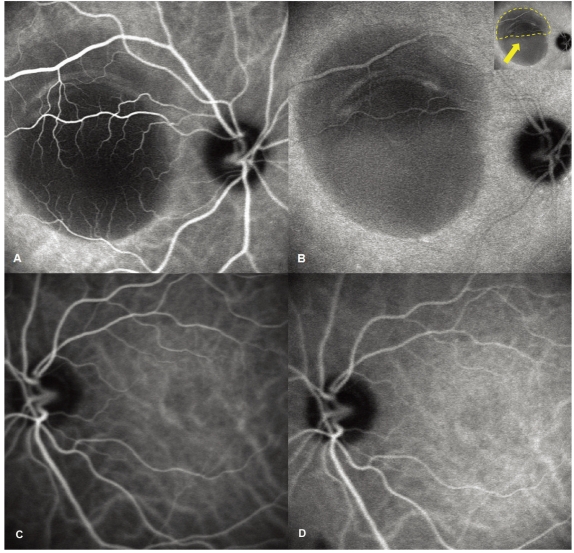

A 71-year-old woman presented with a complaint of sudden decrease in vision in the right eye, 7 days after TKRA. The patient's history was unremarkable except a severe pain of more than the visual analog scale of 8 points for about 2 days, because the analgesic dose given was not adequate for the pain after the surgical operation. On examination the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/100 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. Retinal examination showed a well differentiated serous detachment that was about 3.5 disc diameter in size and located on the macular area in the right eye. No disc edema, retinal cotton wool spots, hemorrhages, or vascular abnormalities were noted in both eyes (Fig. 1). A fluorescein angiography (FA) of right eye performed at the first visit revealed choroidal hypoperfusion and a serous detachment without any leakage points in the early phase of the angiogram (Fig. 2A). In the mid and late phases, the area of non-perfusion showed pooling of the dye in the subretinal space without a leakage point (Fig. 2B, C). Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography was also performed on the same day and showed delayed perfusion of the choriocapillaris without a leakage point in the early phase followed by slow filling of neurosensory detachment without a focal source of leakage in the late phase (Fig. 3A, B). The areas of choroidal hypoperfusion corresponded to the serous detachment seen clinically. There was no disturbance of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). After 2 months, the symptoms and clinical findings began to improve gradually and at the follow-up examination 6 months after the first clinic visit, there was a complete resolution of the serous detachment of macula. The BCVA had improved to 20/20 in the right eye and the fluorescein angiogram showed minor disturbances in the RPE only (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Fundus photographs at the first visit show a serous elevation of the macular area in the right eye.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescein angiogram of right eye performed at the first visit (A) Early phase shows choroidal hypoperfusion (white arrow) and serous detachment (black arrow) without a leakage point, (B)(C) mid and late phases show pooling of the dye in the subretinal space without a leakage point.

Fig. 3.

Indocyanine green angiography angiogram performed at the first visit. (A) Early phase shows delayed perfusion of the choriocapillaris without a leakage point, and (B) late phase shows persistent hypofluorescence (arrow) with slow filling of neurosensory detachment without a focal source of leakage. (C), (D) show no disturbance of the posterior pole in the left eye.

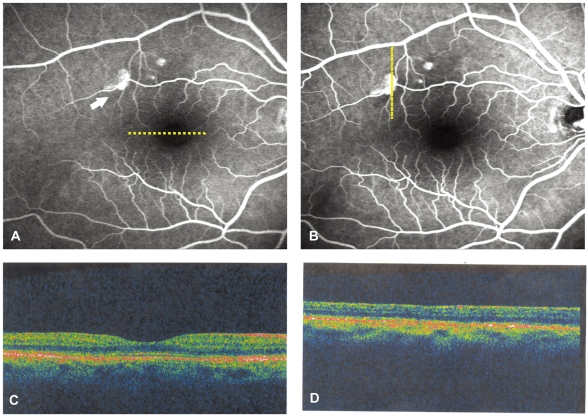

Fig. 4.

Follow-up examination 6 months following the first clinic visit shows complete resolution of the serous detachment of macula. (A) Early phase fluorescein angiogram shows three hyperfluorescent spots (arrow), not seen on previous exam, and (B) late phase fluorescein angiogram shows one of the points leaking slightly and two fade out slowly. Horizontal (C) and vertical (D) crosshair scan of optical coherence tomography at fovea and the leakage point show no serous detachment or pigment epithelium detachment.

Discussion

Serous detachment of the neurosensory retina can occur due to any process that disrupts the outer blood-ocular barrier controlled by the RPE.3 Diagnosis of a serous detachment is made clinically, although optical coherence tomography has recently been used for the detection of clinically occult serous elevations of the retina. The underlying mechanisms of subretinal exudation are thought to include choroidal vascular perfusion and permeability changes, which result in increased choroidal interstitial fluid with further extension into the subretinal space.3 In our case, this 71-year-old woman presented with a unilateral choroidal ischemia with serous macular detachment detected by FA and ICG angiography. The most common cause of this finding is the neovascular form of age related macular degeneration.3,4 However, the patient did not have subretinal hemorrhages, exudates or fibrosis at any time.5 Other signs of choroidal neovascualr membrane including a gray-green membrane and pigment epithelial detachment were also absent. Subretinal leakage, due to altered choroidal vascular perfusion and permeability, occurs in systemic inflammatory and infectious diseases with fluid extension into the subretinal space.3 Systemic malignant hypertension, toxemia of pregnancy, and hypercoagulable states may result in choriocapillaris occlusion and choroidal ischemia with subsequent breakdown of the outer blood ocular barrier and serous detachment.3,6 However, the patient had no significant ophthalmic history and her medical history and review of systems were unremarkable. In addition, there was no history of systemic steroid use. Other causes of serous macular detachment include acute and chronic central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC). However, FA failed to show focal RPE leaks, RPE stippling, or gravitational fluid tracts consistent with CSC.7,8 The ICG angiography showed a slow pooling of ICG in the subneurosensory space but failed to demonstrate focal leaks or frank choroidal leakage as seen in CSC. Idiopathic CSC in a resolving phase with early resolution of fluorescein leakage and persistence of subretinal fluid, might present with serous macular detachment. However, the acute onset of visual loss in a close temporal relationship to severe postoperative pain that interfered with sleep for 2 days after surgery (visual analog scale: 8 points) and the constant pain (visual analog scale: 2~4 points) despite narcotic analgesics suggest a different etiology. A search of the medline database (search words used: choroidal ischemia, pain, serous retinal detachment) showed no studies on choroidal hypoperfusion and serous detachment related to severe pain. Generally, pain reacts to nociceptive stimulation, and primarily secretes histamine or substance P, and serotonin; secondary stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system follows.9 It is possible that the sympathetic innervation produced vasoconstriction and alteration of blood flow in the choroidal vascular beds leading to choroidal hypoperfusion. Compromised function of the retinal pigment epithelium and/or choroid would lead to accumulation of subretinal fluid as is observed in our patient with a serous detachment. A recent survey investigation of the severity of pain, following ambulatory surgery in 5,703 patients, indicated that 30%(1,712) of the patients experienced moderate-to-severe pain postoperatively. However, because individual tolerance to pain varies, patients who have pain do not always present with ocular symptoms.10 Therefore, we propose that severe postoperative pain influences sympathetic activity that can result in ischemic injury with focal choroidal vascular compromise and secondary dysfunction of the overlying REP cells; this may occur in some patients and lead to leakage across the RPE and accumulation of subretinal fluid. Further investigation of the potential impact of pain on the delicate balance of fluid homeostasis, at the outer blood-ocular barrier, may be warranted.

References

- 1.Cogan DG. Ocular involvement in disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:1–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valluri S, Adelberg DA, Curtis RS, Olk RJ. Diagnostic indocyanine green angiography in preeclampsia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:672–677. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70485-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfensberger TJ, Tufail A. Systemic disorders associated with detachment of the neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:455–461. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200012000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowder CY, Gutaman FA, Zegarra H, et al. Macular and paramacular detachment of the neurosensory retina associated with systemic diseases. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;79:347–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fine SL, Berger JW, Maguire MG, Ho AC. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:483–492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002173420707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fastenberg DM, Ober RR. Central serous choroidopathy in pregnancy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1055–1058. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020057010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iida T, Yannuzzi LA, Spaide RF, et al. Cystoid macular degeneration in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2003;23:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yannuzzi LA, Shakin JL, Fisher YL, Altomonte MA. Peripheral retinal detachments and retinal pigment epithelial atrophic tracts secondary to central serous pigment epitheliopathy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1554–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pertovaara A. Noradrenergic pain modulation. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;80:53–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGrath B, Elgendy H, Chung F, et al. Thirty percent of patients have moderate to severe pain 24 hr after ambulatory surgery: a survey of 5,703 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:886–891. doi: 10.1007/BF03018885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]