Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the result of re-operation on the deviated eye of recurred, consecutive or undercorrected sensory strabismus after surgery.

Methods

The medical records of 11 patients who had received second strabismus operation on the deviated eye due to recurred, consecutive or undercorrected sensory strabismus were studied retrospectively.

Results

Among the 11 patients, five patients were operated for recurred exotropia after surgery of sensory exotropia (group 1), two for consecutive exotropia after surgery of sensory esotropia (group 2), and four for undercorrected esotropia after surgery of sensory esotropia (group 3). Re-operation was performed 19.2±12.6 years after the first operation and the mean preoperative deviation before re-operation was 30.0±8.66 prism diopters (PD), 32.5±10.6PD, and 32.5±8.66PD, respectively. In all cases, a small amount of recession or resection compared with the usual surgical dosage was applied in re-operation on the deviated eye. The mean follow-up period after re-operation was 12.3±14.2 (1-48 months). Among the 11 patients, postoperative deviations less than 10PD were achieved postoperatively in 8 (72.7%) at 1 month and of the 8 patients with follow-up data beyond 6 months, 5 (62.5%) showed orthotropia within 10PD at 6 months or later.

Conclusions

The surgical result of re-operation on the deviated eye of recurred, consecutive or undercorrected sensory strabismus after the first surgery was satisfactory in spite of the reduced amount of surgical correction compared with the surgical dosage recommended for the non-operated eye.

Keywords: Recurred sensory strabismus, Re-operation, Sensory strabismus, Strabismus surgery

Sensory heterotropia occurs as a result of primary sensory deficit followed by partial or complete disruption of fusion. Because of the altered tonic vergence movement in sensory heterotropia, the preoperative measured angle of deviation may be inconstant, and the surgical results are less predictable than when visual acuity is normal in each eye. Furthermore, maintaining the postoperatively corrected position of the eyeball is considered difficult because the very nature of sensory heterotropia precludes restoration of binocular function and sensory fusion.1-3

Since most patients with sensory heterotropia want to avoid surgery on the sound eye, as they are very dependent on it, surgery for sensory heterotropia is, if possible, confined to the eye with the visual deficit.4-6 However, in cases of recurred or undercorrected sensory heterotropia, it is difficult to perform re-operation on the deviated eye due to adhesions after the primary surgery, and is often impossible to re-recess or re-resect adequately according to surgical dosage tables on the already recessed or resected muscles. Besides, planning surgery and predicting postsurgical results are difficult due to the occasional unavailability of medical records of the previous surgery. For these reasons, some physicians favor operating on the sound eye for recurred sensory heterotropia. Despite these obstacles, if the surgical result of re-operation on strabismic eye is comparable with that of the primary operation, the physician will not have to operate on the sound eye which can produce discomfort for monocular patients. To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined re-operation on the deviated eye in sensory heterotropia. Therefore, the present study was aimed to evaluate the results of re-operation on the deviated eye of recurred, consecutive or undercorrected sensory strabismus after surgery.

Materials and Methods

The medical records from 1995 to 2006 were reviewed for consecutive patients who had received strabismus surgery on the deviated eye for recurred, undercorrected or consecutive sensory heterotropia after the primary surgery. Patients with best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) ≥20/100 on the deviated eye and patients with strabismic amblyopia were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All patients were informed before surgery of the merits and demerits of re-operation on strabismic eye and were asked to choose which eye they wanted to be operated on.

Through comprehensive history taking and, if available, review of the medical records from the time of the primary operation, the causes of vision loss, type of strabismus, amount of ocular deviation in prism diopters (PD), laterality of the operated eye and the amount of surgery at the time of the primary operation were investigated. BCVA of both eyes, preoperative ocular deviation and amount of surgery, intraoperative findings and postoperative alignment at the time of reoperation were also reviewed. The angle of deviation of sensory heterotropia was measured in PD by modified Krimsky test.

Secondary surgeries were performed by 3 experienced surgeons without immediate postoperative adjustment. Recession or resection of the single rectus muscle, or recession and resection of the horizontal recti muscles were performed in all patients according to the preoperative deviation angle. The amount of surgery was reduced by 1-2 mm compared to that in the surgical table7 so that the total amount of surgery, including the previous one, would be confined to ≤10 mm for the medial rectus muscle and ≤12 mm for the lateral rectus muscle. The surgical amount was measured with a Castroviejo caliper (Storz ophthalmic, E2404, St. Louis, USA) in all patients. All patients were followed up for more than one month.

Results

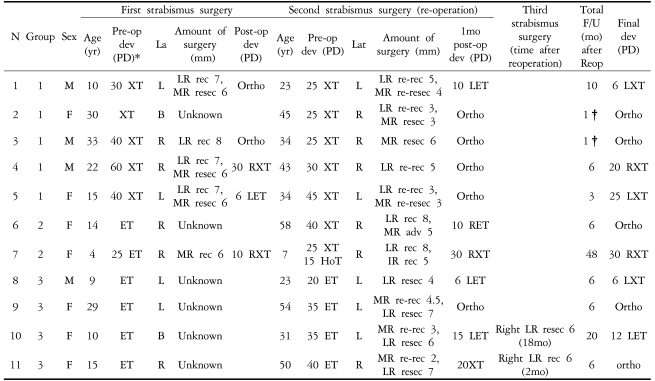

Using the hospital database from 1995 to 2006, 16 patients were found to have had surgery for recurred, undercorrected or consecutive sensory heterotropia. Five of those patients had received re-operation on the non-deviated eye and were excluded from this study. Among the remaining 11 patients, 5 had received re-operation for recurred or undercorrected sensory exotropia (group 1), 2 for exotropia after surgery for sensory esotropia (group 2) and 4 for recurred or undercorrected sensory esotropia (group 3) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data of 11 patients who underwent second strabismus surgery on the deviated eye

Group 1=Surgery on the deviated eye for recurred exotropia after surgery of sensory exotropia on the deviated eye; Group 2=Surgery on the deviated eye for exotropia after surgery of sensory esotropia on the deviated eye; Group 3=Surgery on the deviated eye for recurred esotropia after surgery of sensory esotropia on the deviated eye; F=female; M=male; Dev=deviation; PD=prism diopters; Lat=laterality of operated eye; R=right; L=left; B=bilateral; R(L)ET=right (left) esotropia; R(L)XT=right (left) exotropia; Ortho=orthophoria; MR=medial rectus muscle. LR=lateral rectus muscle; IR=inferior rectus muscle; Post-op=postoperative; F/U=follow-up; Rec=recession; Resec=resection; Reop=reoperation; *insufficient information due to loss of medical chart or incorrect information; †lost to follow-up after 1 month.

The average age of the patients at the time of primary surgery was 17.4±9.7 years (range: 4 to 33 years), and the male to female ratio was 4:7. The causes of vision loss were corneal opacity (2), congenital cataract (2), optic disc coloboma (1), retinal detachment (2) and anisometropic amblyopia (4). Six (54.5%) patients had a history of previous ophthalmic surgery other than strabismus correction: corneal laceration repair (2), cataract extraction and intraocular lens insertion (2), scleral buckling (1) and pars plana vitrectomy surgery (1).

Previous medical records of the primary surgery were available for 5 patients. At primary surgery, 4 exotropic eyes had monocular lateral rectus recession with medial rectus resection and one esotropic eye had medial rectus recession. The remaining 6 patients' medical records were unavailable because they had had the primary surgery many years ago at other hospitals. However, history taking and observation of the conjunctival incision scar revealed that one had bilateral surgery for exotropia, another had bilateral surgery for esotropia and 4 had unilateral surgery on the deviated eye for esotropia.

The average interval between the first and the second operations was 19.2±12.6 years (1 to 44 years) and the average age at the time of the second operation was 36.5±15.3 years (7 to 58 years). The average follow-up after the second operation was 9.64±13.6 months (1 to 48 months).

In group 1, the average deviation was 30.0±8.66PD. In case 2, with no records about the primary operation, the lateral rectus was confirmed to be 6 mm recessed from the original insertion site and the medial rectus was resected, although the amount of resection could not be evaluated. In four patients who had received recession and resection of horizontal recti during the primary operation, the lateral rectus was 3-5 mm recessed and the medial rectus was 3-4 mm resected. In one patient (case 3) who had previously had recession of the lateral rectus muscle, only the medial rectus was resected. One month postoperatively, all patients in group 1 had alignment within 10PD of orthophoria. However, case 4 showed 20PD exotropia at 6 months and case 5 showed 25PD exotropia at 3 months postoperatively.

In group 2, the mean preoperative amount of exodeviation was 32.5±10.6PD. In case 6, with unavailable previous medial records, intraoperative findings revealed that the medial rectus was 6 mm recessed from the original insertion site and that the lateral rectus was resected status. In case 6, lateral rectus recession of 8 mm and medial rectus advancement of 5 mm was performed for 40PD exotropia, and follow-up examination showed 10PD esotropia at 1 month and orthotropia at 6 months. In case 7, who underwent medial rectus recession on primary surgery, lateral rectus of 8 mm recession and inferior rectus recession of 5 mm was performed for 25PD exotropia and 15PD hypotropia. Follow-up examination showed 30PD exotropia at both 1 month and 48 months postoperatively.

In group 3, the mean preoperative exodeviation was 32.5±8.7PD. Although, previous medial records were unavailable in all 4 patients in group 3, intraoperative findings showed that the medial recti were recessed by 5 to 8 mm from the original insertion site. In case 8, the medial rectus was found to be recessed by 8 mm during primary operation, and so, only the lateral rectus muscle was resected for 20PD esotropia in second surgery. In the 3 other patients, the medial recti were recessed by 2-4.5 mm and the lateral recti were resected by 6-7 mm. Cases 8 and 9 showed 6PD esotropia and orthophoria at postoperative 1 month, respectively, and 6PD exotropia and orthophoria at postoperative 6 months, respectively. Case 10 showed 15 and 25PD esotropia at postoperative 1 month and 18 months, respectively, and therefore underwent a third operation (6 mm lateral rectus resection) on the non-deviated normal eye. Follow-up examination at 2 months after the third surgery showed 12PD esotropia. As case 11 showed 20PD exotropia at 1 month after second surgery, 6 mm lateral rectus recession was performed on the deviated eye and follow-up examination after 4 months showed orthotropic.

Overall, 8 (72.7%) of the 11 patients achieved a successful postoperative result (alignment within 10PD of orthophoria) at 1 month. Of the 8 patients with follow-up data beyond 6 months, 5 (62.5%) showed orthotropia within 10PD at the final examination.

Discussion

Treatment of sensory heterotropia is directed toward improving the cosmetic appearance by means of surgical correction.1 In sensory exotropia with a large angle of deviation, straightening the eyes with strabismus surgery is more difficult and undercorrection remains common.3,5,6 The long term maintenance of postsurgical alignment in sensory heterotropia is expected to be poor and the recurrence rate is high due to the low chance of regaining stable fusion.2,3

In sensory heterotropia from monocular visual loss, it is advisable to operate only on the eye with poor vision because it is easier to persuade patients who would be reluctant to undergo surgery on their sound eye.4-6 However, secondary surgery on the deviated eye for recurred sensory heterotropia presents a challenge because an adequate surgical dosage table has not been well established for this situation which renders the results less predictable than those for primary surgery. Besides, medical records of the first surgery in these patients are often unavailable which makes it even more difficult to decide the surgical amount before surgery.

In our study, patients had second surgery at 19.2±12.6 years after the first surgery and the medial records were unavailable in 6 (54.5%) patients. Nevertheless, we decided the surgical dosage and kind of muscle during secondary operation following confirmation of previously operated muscle and recession amount under direct visualization intraoperatively.

Eight (72.7%) of the 11 patients showed alignment within 10PD at 1 month postoperatively. Among the 8 patients who were postoperatively followed up for more than 6 months, 5 (62.5%) showed alignment within 10PD at the last follow-up, an average of 13.5±14.8 months postoperatively. Although the results of strabismus surgery are generally evaluated after long-term follow-up, we considered that the efficacy of the strabismus surgery itself on the sensory strabismus could be evaluated on the basis of the early postoperative results because the surgically corrected alignment of the sensory strabismus cannot be maintained for a long period due to the disruption of fusion.3,8 Our result of 72.7% at 1 month postoperatively was judged to be successful and should enable the reduction of preoperative anxiety which is caused by previous unpredictability of the surgical results. This result is also comparable with those of previous studies for primary surgery on sensory heterotropia, in which a success rate of up to 75% has been achieved.3,9

In the once operated strabismic eye, the dose-effect relationship between surgical amount of reoperation and reduction of deviation angle is very difficult to predict. Some studies have reported on the dose-effect relation between the millimeters of reoperation and the reduction of the deviation angle in the previously operated eye.10,11 However, these studies were performed on small patient groups, and the dose-effect relationship was evaluated for the recession or advancement of only one rectus muscle. Therefore, the results of these studies cannot be applied in the two muscle surgeries of resection and recession, which are commonly used in sensory heterotropia patients. In our study, the two cases of 25PD exotropia (cases 1 and 2) underwent lateral rectus recession by 3-5 mm and medial rectus resection by 3-4 mm. For 35PD esotropia (case 9), the medial rectus was recessed by 4.5 mm and the lateral rectus was resected by 7 mm. In primary surgery for strabismus, we usually perform 6 mm recession of the lateral rectus muscle and 5 mm resection of the medial rectus muscle for 25PD exotropia, and 5 mm recession of the medial rectus muscle and 8mm resection of the lateral rectus muscle for 35PD esotropia, according to the surgical table.7,12 Comparing the amount of surgery in the present study to that of usual primary strabismic surgery, recession and resection were performed by 1-2 mm less, but the result was successful.

An example in which correction of large angle can be achieved even with a small amount of recession is Duane syndrome. Esotropia associated with Duane syndrome can be corrected only by 3.0-3.5 mm resection of the lateral rectus muscle, which is not effective for common esotropia. The lateral rectus muscle in Duane syndrome is stiffer, reduced in elastic muscle fibers and has a reduced arc of contact to the globe which results in a higher length tension curve than that of a normal lateral rectus muscle.13 It is known that the eye with long standing sensory exotropia often develops mechanical abnormalities such as lateral rectus shortening or contracture with limitation, which are similar to those in Duane retraction syndrome.3 In our cases, the average interval between primary and secondary surgeries was 19.2±12.6 years and most of the patients had a history of long standing sensory strabismus. In addition, the previous strabismus surgery in our cases may have caused inflammatory reaction and contributed to extraocular muscles fibrosis and stiffness. In our opinion, these similar characteristics of extraocular muscle in sensory strabismus and Duane retraction syndrome can explain the satisfactory results achieved in our study with a lower amount of surgery than the usual surgical dosage. However, this assumption needs further evaluation.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the results of re-operation in the affected eye of patients with sensory heterotropia. These results will be helpful for surgeons to decide the surgical amount when performing re-operation on the deviated eye in sensory heterotropia. The limitation of our study was the relatively small number of patients due to the lack of sufficient cases of re-operation on sensory heterotropia. Further collaborative study on a larger cohort of patients is needed to confirm our results.

In conclusion, we obtained successful results for the re-operation of the deviated eye in patients with sensory heterotropia by using a smaller amount of resection and/or recession than the surgical dosage recommended for the non-operated eye.

References

- 1.von Noorden GK, Campos EC. Binocular vision and ocular motility. 6 th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 2002. pp. 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelman PM, Brown MH. The stability of surgical results in patients with deep amblyopia. Am Orthopt J. 1977;27:103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum AL, Santiago AP. Clinical Strabismus Management. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1999. pp. 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright KW, Spiegel PH. Pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2003. p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens PL, Strominger MB, Rubin PA, et al. Large angle exotropia corrected by intraoperative botulinum toxin A and monocular recession resection surgery. J AAPOS. 1998;2:144–146. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raab EL. Unilateral four muscle surgery for large angle exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:1441–1450. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(79)35377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foundation of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basis and clinical science course. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2006. pp. 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson JM, Kousoulides L, Lee JP. Long term results of botulinum toxin in consecutive and secondary exotropia: outcome in patients initially treated with botulinum toxin. J AAPOS. 1998;2:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott WE, Kutschke PJ, Lee WR. 20th annual Frank Costenbader Lecture adult strabismus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1995;32:348–352. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19951101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yazdian Z, Ghiassi G. Re recession of the lateral rectus muscles in patients with recurrent exotropia. J AAPOS. 2006;10:164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langmann A, Lindner S, Koch M, et al. Dose-effect relation in revision surgery for consecutive strabismus divergens in adults. Ophthalmologe. 2005;102:869–872. doi: 10.1007/s00347-005-1210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spierer A, Ben Simon GJ. Unilateral and bilateral lateral rectus recession in exotropia. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2005;36:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morad Y, Kraft SP, Mims JL., 3rd Unilateral recession and resection in Duane syndrome. J AAPOS. 2001;5:158–163. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2001.114187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]