Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. The Global Burden of Disease study has concluded that COPD will become the third leading cause of death worldwide by 2020, and will increase its ranking of disability-adjusted life years lost from 12th to 5th. Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) are associated with impaired quality of life and pulmonary function. More frequent or severe AECOPDs have been associated with especially markedly impaired quality of life and a greater longitudinal loss of pulmonary function. COPD and AECOPDs are characterized by an augmented inflammatory response. Macrolide antibiotics are macrocyclical lactones that provide adequate coverage for the most frequently identified pathogens in AECOPD and have been generally included in published guidelines for AECOPD management. In addition, they exert broad-ranging, immunomodulatory effects both in vitro and in vivo, as well as diverse actions that suppress microbial virulence factors. Macrolide antibiotics have been used to successfully treat a number of chronic, inflammatory lung disorders including diffuse panbronchiolitis, asthma, noncystic fibrosis associated bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis. Data in COPD patients have been limited and contradictory but the majority hint to a potential clinical and biological effect. Additional, prospective, controlled data are required to define any potential treatment effect, the nature of this effect, and the role of bronchiectasis, baseline colonization, and other cormorbidities.

Keywords: macrolide therapy, antibiotics, AECOPD

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects between 12 and 24 million people in the United States, where it is the fourth leading cause of death, accounting for over 106,000 deaths in 1996. Worldwide, COPD is the sixth leading cause of death (Petty 2000; Ward et al 2000; Halbert et al 2003; Halpern et al 2003; Wouters 2003) and is the only condition in the top 10 causes of death with an increasing prevalence and mortality (Pauwels et al 2001; Mannino et al 2002; Petty 2000; Stoller 2002). The Global Burden of Disease study undertaken by the World Bank and the World Health Organization concluded that COPD will become the third leading cause of death worldwide by 2020, and its ranking relative for number of disability-adjusted life-years lost will increase from 12th to 5th (Gulsvik 2001). Currently, oxygen therapy for hypoxemic patients and cigarette-smoking cessation are the only interventions known to alter the natural history of COPD.

Although an exact definition of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) remains controversial (Pauwels et al 2004), a generally accepted definition is that of ‘a sustained worsening of the patient’s condition, from the stable state and beyond normal day-today variations, that is acute in onset and necessitates a change in regular medication in a patient with underlying COPD’ (Rodrigues-Roisin 2000). Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) account for about 13 million office visits each year in the US (Niederman et al 1999; Sethi 1999; Gonzales et al 2001), and account for 31%–68% of the total cost of COPD in the US and Europe (Ward et al 2000; McGuire et al 2001; Strassels et al 2001; Andersson et al 2002; Miravitlles et al 2002). In 1996, acute exacerbations of COPD resulted in the sixth highest use of hospital bed days/yr in the US (176 million) and the sixth highest number of days lost from work (57.5 million) (Druss et al 2002). As such, AECOPDs are a major source of health-care expenditure (Halpern et al 2003). This cost is particularly evident in those AECOPDs that require hospitalization (Miravitlles et al 2002; Oostenbrink and Ruttenvan Molken 2004).

The negative implications of AECOPDs have been highlighted by numerous investigators. A review of eighteen studies confirmed that AECOPD worsen health-related quality of life (HRQL) (Schmier et al 2005). A two-year longitudinal study noted that more frequent exacerbations had a deleterious effect on health status in patients with moderate disease (forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] 35%–50% predicted) (Miravitlles et al 2004). The greatest improvement in HRQL occurs during the first four weeks after a single episode, although continued improvement occurs over 26 weeks. Conversely, recurrence of AECOPD markedly attenuates improvement (Spencer et al 2003).

AECOPDs also result in measurable, albeit modest, acute effects on pulmonary function (Seemungal et al 2000). A modest improvement in pulmonary function, particularly in lung volume, has been reported over the first several weeks after therapy is initiated (Parker et al 2005; Stevenson et al 2005) Repeated AECOPDs are associated with loss of pulmonary function; the decrement in FEV1 has ranged from 7–8 mL/yr for patients with more frequent episodes (Donaldson et al 2002; Kanner et al 2001).

Thus, AECOPD are associated with very significant healthcare expenditures, deterioration in HRQL that may be sustained, and appreciable deterioration in pulmonary function. Accordingly, preventing AECOPDs, or reducing their severity, should have favorable clinical, physiological and economical effects in COPD patients.

COPD is an inflammatory disease

Over the past several years, numerous studies have confirmed the important role of inflammation in the airways and lung parenchyma of COPD (Hill et al 1999; Sethi 2000; Aaron et al 2001; Gompertz et al 2001; Wedzicha 2002; Pietila and Thomas 2003; White et al 2003). Many have advocated a central pathogenic role of this inflammatory response (Hogg et al 2004; Shapiro and Ingenito 2005; Traves and Donnelly 2005; Wouters 2005). This inflammatory response contributes to the increased oxidative stress noted during an AECOPD (Tsoumakidou et al 2005). Both neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammation have been described, with a multitude of inflammatory mediators implicated including interleukin-8 (IL-8), leukotriene B4 (LTB4), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GMCSF), regulated upon activation: normal T cell expressed/secreted (RANTES), and endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Hill et al 1999; Sethi 2000; Gompertz et al 2001; Roland et al 2001; White et al 2003). One group followed 68 patients with COPD and an emphysematous phenotype for 2–3 years, with 30 developing an AECOPD associated with expectorated sputum adequate for analysis (Fujimoto et al 2005). During an AECOPD, total sputum cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, IL-8, neutrophil elastase, eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP), and RANTES increased compared to the stable state. Prospective studies using bronchoscopic techniques have confirmed increased expression of RANTES in both the surface epithelium and subepithelial lymphomononuclear cells, increased numbers of neutrophils, as well as increases in CXCL5 (ENA-87), CXCL8 (IL-8), and CXCR2 during an AECOPD (Zhu et al 2001; Qiu et al 2003; Drost et al 2005). Collectively, these data confirm a local, inflammatory process and increased oxidant stress status during exacerbations. Novel pathways promulgating this inflammatory response have recently been defined (Ito et al 2005).

As COPD progresses, the lungs are infiltrated by activated macrophages (Rutgers et al 2000; Amin et al 2003; Caramori and Adcock 2003) and lymphocytes (Saetta et al 1993; O’Shaughnessy et al 1997; Hogg et al 2004). Macrophages and lymphocytes, are not only increased in the airways and alveoli in COPD (Di Stefano et al 2004; Shapiro and Ingenito 2005), but the prevalence of these two cell types, rather than of neutrophils as previously suspected, correlates with the severity of airflow obstruction (Di Stefano et al 1996, 2001; O’Shaughnessy et al 1997; Kemeny et al 1999; Hill et al 2000; Turato et al 2002; Hogg et al 2004) and emphysema (Finkelstein et al 1995; Russell, Culpitt, et al 2002; Russell, Thorley, et al 2002).

Macrophages are key cells of the innate immune system, secreting cytokines and chemokines when stimulated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Many of the lung lymphocytes are type 1 cytokine-producing CD8 T cells (Saetta et al 1998, 1999, 2002; Majo et al 2001; Grumelli et al 2004). The CD8+ T cells predominance has been most evident in studies that used chronic bronchitis as an entry criteria (Saetta et al 1997), and is less evident when study design selected against chronic bronchitis (Hogg et al 2004). Although macrophages and CD8+ T cells could synergistically contribute to progressive lung destruction in COPD in several ways (Barnes et al 2003), the exact mechanism remains unproven. The systemic nature of COPD and AECOPDs have been recently documented (Agusti 2005). Plasma fibrinogen, IL-6, C-reactive protein, and endothelin-1 concentrations increase during AECOPDs (Dev et al 1998; Wedzicha 2000; Roland et al 2001; Hurst et al 2006).

Lung infections increase the inflammation of COPD

Various infectious and noninfectious stimuli can stimulate the inflammatory response associated with an AECOPD. Environmental pollutants, including particulate matter and nonparticulate gases can provoke an inflammatory response in-vitro and in in-vivo (Devalia et al 1994; Ohtoshi et al 1998; Rudell et al 1999). Epidemiological studies have suggested increased respiratory symptoms and mortality during times of increased air pollution (Sunyer et al 1993; Garcia-Aymerich et al 2000; Sunyer et al 2000). Despite these data, a large proportion of AECOPDs are felt to reflect infection, whether bacterial or viral (Sethi 2004). Viral infections are a well recognized cause of AECOPD (Wilkinson et al 2004; Johnston 2005). The most frequently reported agents include rhinovirus, coronavirus, influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and human metapneumovirus (Stott et al 1968; Gump et al 1976; Seemungal et al 2001; Greenberg 2002; Rhode et al 2003; Tan et al 2003; Pletz et al 2004; Wedzicha 2004; Hamelin et al 2005).

Atypical infectious agents, including Chalmydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Legionella species, have been reported to cause AECOPD, although the majority of the data involve C. pneumoniae (Beaty et al 1991; Blasi et al 1993; Mogulkoc et al 1999; Karnak et al 2001; Lieberman et al 2001; Seemungal et al 2002). The etiologic role of bacteria in individual AECOPD episodes has been a subject of much controversy (Hirschmann 2000; Murphy et al 2000). Recent comprehensive reviews have highlighted the evolution of these concepts (Sethi and Murphy 2001; Sethi 2004). Sputum cultures have been the classic methodological approach to identifying potentially pathogenic bacteria in AECOPD, with the most frequently isolated organisms being nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Other, less frequently identified organisms include Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative rods. Pseudomonas spp. or other enteric Gram-negative rods have been identified in the sputum of patients with greater airflow obstruction (Eller et al 1998; Miravitlles et al 1999) and prior use of antimicrobial agents (Monso et al 2003).

Bronchoscopic studies using bronchoalveolar lavage or protected specimen brush have confirmed that potentially pathogenic bacteria are identified in many COPD patients at baseline and during AECOPDs (Fagon et al 1990; Monso et al 1995; Pela et al 1998; Soler et al 1998). An analysis of pooled data from six published studies confirmed a high frequency of colonization in stable COPD patients in contrast with healthy subjects; a clear shift to higher potentially pathogenic organism load was noted during an AECOPD (Rosell et al 2005). Importantly, several groups have demonstrated that bacterial colonization, as defined by sputum cultures, is associated with a greater sputum and systemic inflammatory response, more frequent clinical AECOPD episodes and greater symptoms and worse health status (Soler et al 1999; Bresser et al 2000; Hill et al 2000; Patel et al 2002; Banerjee et al 2004).

Novel methodological approaches have provided even more compelling data implicating bacterial pathogens in AECOPD. The longitudinal use of sputum culture and molecular typing of bacterial pathogens isolated from sputum has demonstrated that acquisition of a bacterial strain with which the patient had not been previously infected is associated with a greater than twofold increase in the risk of an exacerbation (Sethi et al 2002). Although the identification of a new strain of nontypeable H. influenzae was not associated with a symptomatic exacerbation in the majority of patients, collaborative work has highlighted inherent differences in new H. influenzae strains associated with symptomatic exacerbations which lead to greater neutrophil recruitment, adherence to epithelial cells and greater IL-8 release from epithelial cell cultures compared to those not associated with such a clinical response (Chin et al 2005). A similar approach has confirmed the same increased risk of AECOPD for M. catarrhalis (Murphy et al 2005).

An immune response to one or more microbial pathogens has been utilized recently to define further the role of bacteria in individual AECOPD episodes. This methodological approach has been most widely reported for H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis (Musher et al 1983; Yi et al 1997; Bakri et al 2002; Sethi 2004; Murphy et al 2005), and to examine the interaction between bacterial and viral infection (Bandi et al 2003). In one such study, 16/35 exacerbations (46%) were associated with evidence of acute viral infection, whereas 11 (31%) were associated with the development of new serum IgG to homologous H. influenzae isolates; evidence of a viral infection was identified in 24/35 exacerbations (79%) (Bandi et al 2003). These data show that viral and bacterial infections can co-exist during symptomatic AECOPD, although antecedent viral infection is not required for H. influenzae- associated exacerbations.

Macrolides in COPD

Treatment of AECOPD

Given compelling data that bacterial infection is likely etiologic in approximately 50% of AECOPDs, it is not surprising that antimicrobial therapy has been intensively studied in this disease. Numerous placebo-controlled trials of antibiotics in AECOPDs have been published, with systematic reviews suggesting a modest treatment effect favoring antimicrobial therapy (Bach et al 2001; McCrory et al 2001; Saint et al 2001). Saint and colleagues (2005) examined nine placebo controlled trials and concluded that there was a small but statistically significant improvement with antibiotic therapy, which was especially significant in patients with low baseline flow rates. The American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Physicians, and the American Society for Internal Medicine systematically analyzed 11 randomized, placebo-controlled studies of antibiotic treatment and also concluded that antibiotics are beneficial (Bach et al 2001; McCrory et al 2001; Snow et al 2001). Additional studies have been published since these systematic reviews were published. Allegra and colleagues (2001) noted that overall clinical response rate was improved with amoxicillin-clavulanate versus placebo in a multi-center trial in well-defined AECOPD; response clearly varied by the severity of baseline airflow obstruction, with the greatest difference between placebo and antimicrobial agent noted in patients with the lowest FEV1. Nouria and colleagues (2001) demonstrated dramatic improvement with ofloxacin therapy compared with placebo in a group of patients with severe COPD admitted with respiratory failure.

Based on data such as these, most recent international guidelines have incorporated recommendations as to which AECOPD patient is more likely to have bacterial infection likely to benefit from an antimicrobial agent (Blasi et al 2006). Patients with at least two cardinal symptoms of an AECOPD (increase in dyspnea, increase in sputum production, and/or change in sputum color) experience a benefit with antibiotic therapy (Anthonisen et al 1987). An exacerbation associated with sputum purulence may also be more likely to benefit from antibiotic treatment (Stockley et al 2000; Wilson 2005). Increasing sputum purulence has been clearly associated with bacterial growth in sputum samples (Allegra et al 2005; Blasi et al 2006). Measurement of serum procalcitonin levels have recently been suggested to define AECOPD patients with a higher likelihood of bacterial infection (Reichenberger et al 2001; Christ-Crain et al 2004). Hence, the available data suggest that antimicrobial therapy provides benefit in carefully selected patients with more severe disease and more severe exacerbations.

Numerous controlled trials have compared newer agents with established ones. These studies have generally been designed as noninferiority trials for registrational purposes and therefore provide limited comparative information regarding clinical response for various antimicrobial classes (Miravitlles and Torres 2004; Sethi 2004; Wilson 2005). Not surprisingly, clinical response in these trials is generally similar among different antimicrobial classes. However, more recent trials using novel experimental designs have suggested interesting differences between different antimicrobial classes. For example, in defining ‘bacterial eradication’ by sputum culture, White and colleagues (2003) noted that patients with persistent bacteria after a ten day course of antimicrobial therapy exhibited elevated sputum inflammatory markers. In addition, some investigators have suggested that a more rapid resolution of symptoms may be seen with quinolones in contrast to comparator agents (Miravitlles et al 2004; Martinez et al 2005). These data suggest that eradication of bacterial pathogens may be associated with important clinical outcomes.

The most provocative data have revolved around the finding that some agents may lengthen the disease-free interval (DFI), ie, the time between exacerbations (Anzueto et al 1999; Saint et al 2001; Chodosh 2005; Wilson 2005). Because antimicrobial therapy that completely eradicates bacteria is associated with reduced inflammation (White et al 2003), such agents should result in greater symptomatic resolution and better long-term clinical outcomes (Anzueto et al 1999; Chodosh 2005; Wilson 2005). Based on these considerations, AECOPD clinical trials have increasingly, incorporated an assessment of how different antibiotics affect the DFI (Martinez et al 2005). An early study demonstrated equivalence between antibiotics in short-term clinical response, although post-hoc analysis suggested that failure to clear the organism from the sputum post-therapy was associated with a shorter DFI (Chodosh et al 1998). Wilson and colleagues (2002) noted fewer recurrences of AECOPD with gemifloxacin (29%) compared to clarithromycin (41.5%, P = 0.016). The MOSAIC study investigators contrasted moxifloxacin with various comparators (cefuroxime, clarithromycin or amoxicillin) (Wilson et al 2004). Although all antibiotics resulted in equivalent short-term clinical response, moxifloxacin-treated patients required fewer additional antibiotics and experienced a longer DFI. In contrast, Lode and colleagues (2004) did not demonstrate a difference between levofloxacin and clarithromycin with respect to the DFI, although the patient population was a bit less ill. Thus, the effect of antibiotic class on DFI remains a crucial endpoint for future studies of AECOPD.

In general, macrolides have provide adequate coverage for the most frequently identified pathogens in AECOPD (Martinez 2004), although differences among the compounds in H. influenzae activity have been evident. For example, azithromycin appears to have improved bacteriologic and clinical activity relative to clarithromycin (Martinez et al 2005). The role of the macrolides in AECOPD therapy remains controversial although they have been generally included in published guidelines (Balter et al 2003; Pauwels et al; Martinez 2004; Woodhead et al 2005; Blasi et al 2006). These guidelines usually advocate stratification of patients by likelihood of clinical failure, with macrolide therapy suggested for patients with milder underlying disease, a low likelihood of infection with organisms which are not covered with standard antibiotic regimens (eg, P. aeruginosa, drug-resistant bacteria), or host factors that predict treatment failure.

Macrolides as immunomodulatory agents

Macrolides are macrocyclical lactones consisting of greater than 8-membered rings. This very large class (>2000 compounds) comprises both natural substances isolated from fungi and other organisms, as well as synthetic molecules of a similar structure (Jain and Danziger 2004). The most commonly, clinically used agents are semi-synthetic 14-, 15-, or 16-membered ring antibiotics related to erythromycin (Figure 1). These include erythromycin, roxithromycin and clarithromycin as typical members of the 14-member class, and azithromycin as the prototypical 15-member compound (Labro 2004). Macrolide antibiotics bind to 50S ribosomes of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, inhibiting transpeptidation or translocation of nascent peptides. Macrolides have good bioavailability by the oral route, superb tissue penetration, favorable side-effect profiles, and prolonged tissue persistence. For these reasons, and their broad efficacy against Gram-positive, some Gram-negative, mycobacterial, chlamydial, mycoplasmal, and Legionella species, macrolides are well established in the therapy of respiratory infections.

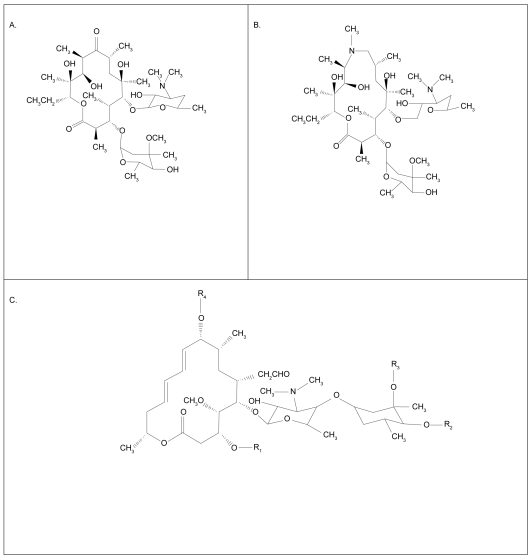

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of 14 member macrolides (erythromycin, A), fifteen member compounds (azithromycin, B) and a 16 member compound (C) (Jaffe and Bush 2001).

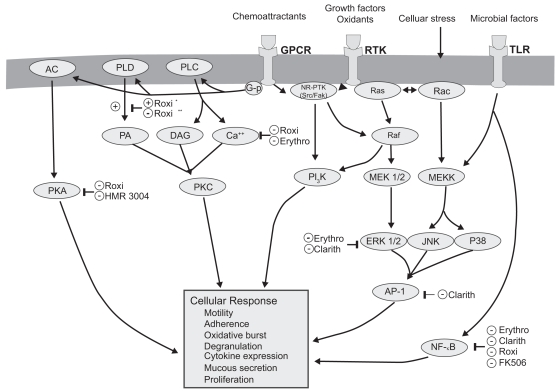

Macrolides exert broad-ranging immunomodulatory effects on mammalian cells in vitro and in vivo, as comprehensively reviewed by others and briefly summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 2 (Zalewska-Kaszubska and Gorska 2001; Labro 2004; Tsai and Standiford 2004). Among their many activities, macrolides have been shown to exert effects on a wide range of cells including nasal and bronchial epithelial cells, alveolar macrophages, monocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes. The effect on signaling pathways including NF-κB and AP-1 (Desaki et al 2000, 2004, Kikuchi et al 2002) is evident in Figure 2. Macrolides exert a host of effects that collectively limit tissue damage by neutrophils. In addition to effects on chemoattractants, these include inhibiting their oxidant burst, impairing degranulation, and increasing the rate of neutrophil apoptosis. There is also evidence that macrolides decrease mucus viscosity (Tamaoki et al 1995), and suppress angiogenesis (Yasunami and Hayashi 2001). Importantly, all these immunomodulatory effects are evident at concentrations attainable clinically by low-dose administration, and are not seen using 16-member macrolides. Most immunomodulatory effects are shared by the 14- and 15-member agents, although in some cases the effects vary among the individual compounds. For example, roxithromycin appears to exhibit consistent effects in vitro and in vivo (Agen et al 1993; Scaglione and Rossoni 1998). Similarly, clarithromycin and azithromycin induce apoptosis of peripheral blood lymphocytes to a qualitatively greater extent than josamycin (Ishimatsu et al 2004). Hence, macrolides have many properties that could mitigate the neutrophilic inflammation central to airway damage, and might also improve aspects of airflow obstruction.

Figure 2.

Molecular targets of macrolides (Tsai and Standiford 2004).

Macrolides also exert diverse actions that suppress microbial virulence factors (Shryock et al 1998; Pechere 2001; Wozniak and Keyser 2004). Although P. aeruginosa possesses high innate resistance in vitro (MIC ≥ 128 μg/ml), macrolides accumulate within the microbes over time, and suppress elaboration of elastase, lecithinase, and pyocyanin. Macrolides also alter the structure of LPS and outer membrane proteins, with a net effect of decreasing microbial adhesion to host cells. By in hibiting alginate production, macrolides destroy pseudomonal biofilm, facilitating killing by other antibiotics. Finally, sub-inhibitory concentrations of macrolides impede microbial motility of both P. mirabilis and P. aeruginosa by inhibiting flagellin synthesis. Importantly, these activities are also common to 14- and 15-ring macrolides, and have not seen using rokitamycin, a 16-member ring macrolide that has potent bactericidal activity against susceptible organisms. Furthermore, differences among individual agents have been reported with azithromycin exhibiting the greatest effect on quorum sensing (Molinari et al 1993). Given these immunomodulatory properties and unique effects on bacterial pathogens macrolide antimicrobial agents have the potential to serve a unique role in the management of chronic inflammatory lung disorders, including COPD.

Macrolides in non-COPD chronic pulmonary inflammatory disorders

Macrolides have increasingly been used for their immunomodulatory properties in a wide range of chronic disorders. These will not be discussed in detail but results in chronic, inflammatory pulmonary disorders will be highlighted with a goal of presenting the rationale for their potential use in COPD.

Diffuse panbronchiolitis

Diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the respiratory bronchioles and adjacent centrilobular regions. It is seen mainly, but not exclusively, in Japan, and presents with chronic cough, exertional dyspnea, and reticulonodular infiltrates on chest radiography (Koyama and Geddes 1997). Chronic sinusitis is almost always noted. In fact, in geographical locations where this disease is found, the presence of airflow obstruction and chronic sinusitis in a nonsmoker should immediately raise suspicion of DPB. The appearance on high resolution computed tomography of the chest is characteristic (Akira et al 1988; Nishimura et al 1992). Early in the disease course, H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae are cultured from respiratory secretions, while in many cases P. aeruginosa is noted in advanced stages (Kadota et al 2003).

The majority of investigators have confirmed a marked increase in neutrophils in BAL fluid of DPB patients (Ichikawa et al 1993; Mukae et al 1995; Kadota et al 2001; Hiratsuka et al 2003). The percentage of neutrophils appears to be higher in DPB patients with P. aeruginosa infection (Oishi et al 1994). Not unexpectedly, neutrophil chemotactic activity is markedly increased in DPB patients compared to normal, healthy volunteers (Kadota et al 1993; Oda et al 1994). Similarly, DPB patients have high concentration of IL-8 in BAL fluid (Sakito et al 1996), particularly in those infected with P. aeruginosa (Oishi et al 1994). Importantly, the histologic pattern of DPB includes bronchiolar wall thickening with an infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes (Homma et al 1983). Some investigative groups have noted that DPB patients have a higher number of lymphocytes and a reduced CD4/CD8 ratio compared to patients with idiopathic bronchiectasis and healthy subjects (Mukae et al 1995). β-defensins have noted to be elevated in the BAL fluid of DPB patients, with the plasma concentration of β-defensin 2 (HBD-2) correlating with the concentration in BAL fluid (Hiratsuka et al 2003). All these findings support a central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of DPB, and suggest that Pseudomonas involvement is at least associated with more severe involvement, and may contribute to an accelerated deterioration.

Prior to the onset of chronic macrolide therapy, the prognosis of DPB was dismal, with a 10 year survival of approximately 75% in cases without P. aeruginosa infection but less than 22% with P. aeruginosa infection (Koyama and Geddes 1997; Kudoh et al 1998). In the mid-1980’s, Kudoh and colleagues first noted that erythromycin therapy improved outcome in DPB (Kudoh et al 1984; Kudoh et al 1987). Subsequent case series (Koyama and Geddes 1997) and a randomized, placebo-controlled trial confirmed this beneficial effect (Yamamoto 1991). Importantly, this favorable effect was independent of the presence of P. aeruginosa infection (Sawaki et al 1986; Nagai et al 1991) or the presence of chronic respiratory failure (Ohno et al 1993). In addition to erythromycin, beneficial results have been confirmed with clarithromycin (Takeda et al 1989), roxithromycin (Ashitani et al 1992; Nakamura et al 1999), and azithromycin (Kobayashi et al 1995).

Increasing mechanistic insight on the clinical effects of macrolide therapy in DPB has become available. Improved symptoms, pulmonary function and arterial blood gases have been noted regardless of the presence of Pseudomonas infection, although there appears to be less marked improvement in pulmonary function in patients in whom bacteria persist after macrolide therapy, compared to those in whom sputum cultures become negative (Fujii et al 1995). As such, the effect of macrolides is unlikely to exclusively reflect an antibacterial effect, as clinical improvement may be seen despite lack of change in bacterial isolates or number in at least 50% of treated patients (Kadota et al 2003; Nakamura et al 1999).

Numerous investigators have demonstrated favorable effects of macrolide therapy on the inflammatory process in DPB. It is unlikely that the effect is purely a result of the antibacterial activity of the macrolide, because the maximal serum and sputum levels of erythromycin have been documented to be below the MICs of the clinically identified isolates (H. influenzae and P. aeruginosa) (Nagai et al 1991). Supporting an anti-inflammatory effect, clinical treatment with a macrolide has been shown to decrease neutrophils (Ichikawa et al 1993; Kadota et al 1993; Oda et al 1994; Oishi et al 1994; Fujii et al 1995; Nakamura et al 1999; Hiratsuka et al 2003), neutrophil chemotactic activity (Kadota et al 1993; Oda et al 1994), neutrophil-derived elastolytic-like activity (Ichikawa et al 1993), and concentrations of IL-8 and LTB4 (Nakamura et al 1999). The latter has been shown to be independent of the ability to ‘eradicate’ organisms from sputum culture. However, patients in whom bacteria persist despite chronic macrolide therapy are less likely to experience improvement in BAL fluid neutrophil percentage (Fujii et al 1995). In addition, macrolide therapy decreases the percentage of BAL lymphocytes and BAL concentration of HBD-2, which suggests a primary effect on the underlying pathogenic process (Hiratsuka et al 2003). In summary, these data confirm that marked beneficial effects are seen with macrolide therapy in DPB patients, and these effects likely reflect the anti-inflammatory properties of these agents and in addition to potential antimicrobial effects. The similarities to potential effects in COPD are evident.

Macrolides in asthma

Asthma has a number of biological features that are distinct from COPD (Douwes et al 2002; Sutherland and Martine 2003). Macrolide antibiotics have been utilized in asthma for more than forty years. For example, troleandomycin (TAO) was extensively studied as a steroid-sparing agent in asthma (Niven and Argyros 2003), with inconclusive results (Evans et al 2003). Other investigators have examined more widely available macrolide agents. The most widely reported outcome has been a modest improvement in bronchial hyperresponsiveness (Miyatake et al 1991; Shimizu et al 1994; Kamoi et al 1995; Amayasu et al 2000; Kostadima et al 2004). Clinical response has been more difficult to judge in uncontrolled studies (Garey et al 2000). Several controlled trials have been published, as has a recent Cochrane systematic review (Richeldi et al 2005). In general, these studies have documented modest symptomatic improvement but little change in standard spirometric indices (Shoji et al 1999; Amayasu et al 2000).

Other investigators have provided mechanistic data regarding the effect of macrolide therapy in patients with asthma. Kraft and colleagues (2002) noted improved FEV1 in patients with evidence by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of mycoplasma or chlamydia in upper or lower respiratory tract specimens (38/55 patients). PCR-positive patients treated with clarithromycin experienced a decrease in TNF-α, IL-5 and IL-12 mRNA in BAL fluid and TNF-α mRNA in airway tissue; PCR-negative patients treated with clarithromycin exhibited decreased TNF-α and IL-12 mRNA in BAL and TNF-α mRNA in airway tissue. No significant changes were seen in subjects treated with placebo. Black and colleagues (2001) conducted a multicenter, multinational study of 232 adults with mild to moderate asthma and serological evidence of C. pneumoniae infection, randomizing patients to roxithromycin 150 mg bid or placebo for six weeks. A modest increase in peak expired flow was noted in the macrolide treated patients after six weeks; daytime and nighttime symptoms showed nonsignificant improvements, as did improved quality of life scores. The differences between these two studies may reflect disparity in patient characteristics at baseline, differing macrolides administered, and differing definition of an atypical infection. These points may be important in interpreting data in COPD patients, in whom chronic infection with Chlamydia has been felt to be important (Blasi et al 2002).

Macrolides in noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is a disorder of the bronchi and bronchioles manifesting cough, chronic sputum production, dyspnea, and wheezing (Barker 2003). The cornerstones of therapy include early identification and treatment of acute exacerbations, suppression of the microbial load, treatment of underlying conditions, promotion of bronchial hygiene, control of bronchial hemorrhage, surgical resection of extremely damaged/focal disease and reduction of excessive pulmonary inflammation (Barker 2003).

It is likely that bronchiectasis involves a vicious cycle of infection with subsequent inflammation and mediator release. Investigators have confirmed an intense cellular infiltrate with mononuclear cells (CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages), a prominent neutrophilia and increased IL-8 expression (Gaga et al 1998). Increased expression of IL-8 and other potent chemoattractants (TNF-α and LTB4) have also been reported (Angrill et al 2001; Richman-Eisenstat et al 1993; Tsang et al 2000). In addition, patients colonized with potentially pathogenic organisms experience a greater inflammatory response which includes higher BAL neutrophil count and higher BAL concentrations of elastase, myeloperoxidase, TNF-α and IL-8 (Angrill et al 2001).

Bronchiectasis patients with P. aeruginosa in the sputum have more severely impaired pulmonary function and greater sputum volume (Ho et al 1998). These patients also appear to exhibit the highest concentration of TNF-α and LTB4 (Tsang et al 2000). It is evident that bronchiectasis is characterized by augmented airway inflammation that appears related to bacterial colonization, organism load and differing bacterial species.

A small number of studies have examined the effect of chronic macrolide therapy in bronchiectasis unrelated to cystic fibrosis. After 12 weeks of roxithromycin (4 mg/kg bid) children with bronchiectasis and increased airway hyperreactivity experienced little change in FEV1 but experienced improvement in sputum purulence and airway responsiveness (Koh et al 1997). In a placebo-controlled trial, Tsang and colleagues (1999) administered erythromycin (500 mg bid) for eight weeks to 11 patients with bronchiectasis (Tsang et al 1999). P. aeruginosa was identified at baseline in ten of the patients and H. influenzae in the eleventh. Patients treated with macrolides experienced an improvement in spirometry and 24-hour sputum volume, but no parallel improvement in sputum pathogens, sputum leukocytes, or levels of IL-1α, IL-8, TNF-α or LTB4 (Tsang et al 1999). Tagaya and colleagues (2002) noted improved sputum production in 16 patients with bronchiectasis (n = 11) or chronic bronchitis (n = 5) treated with clarithromycin (400 mg/day) compared to patients treated with amoxicillin or cefaclor. Davies and Wilson (2004) examined thrice weekly (after initial loading) azithromycin therapy in 39 patients with bronchiectasis, greater than four exacerbations in the previous 12 months, and persistent symptoms. Only modest improvements were noted in pulmonary function, although symptoms scores and acute exacerbations decreased; these findings were independent of P. aeruginosa colonization. In a small, cross-over study, Cymbala and colleagues (2005) noted a decrease in acute exacerbation rate and mean 24-hour sputum volume, but no change in pulmonary function with twice weekly azithromycin therapy for six months. These data are particularly germane, given the frequent development of bronchiectasis following AECOPD (O’Brien et al 2000).

Macrolides in cystic fibrosis

A robust body of literature has emerged demonstrating that macrolide antibiotics are beneficial in the treatment of cystic fibrosis (CF) lung disease (Equi et al 2002; Wolter et al 2002; Saiman et al 2003; Southern et al 2005). Numerous studies have strengthened the conclusion that there is excessive inflammation in CF airways. Khan and colleagues (1995) noted higher inflammatory cells and mediators in infants with CF, even when no evidence of bacterial infection was identified. This augmented inflammatory response may be intrinsic to CF airway epithelial cells, as DiMango and colleagues (1998) noted that in response to Pseudomonas, epithelial cells having mutations in the cystic fibrosis gene (CFTR) elaborated higher levels of inflammatory mediators than cells with normal CFTR.

As with other inflammatory pulmonary disorders, a high prevalence of chronic airway infection occurs in CF. P. aeruginosa appears to be the most prevalent organism, with 80% of patients infected by 18 years of age (Trulock et al 2003). This infection has major consequences, as the survival of CF patients harboring Pseudomonas aeruginosa is shorter than that of CF patients uninfected by Pseudomonas.

A series of studies have confirmed the benefit of macrolide therapy in CF. Jaffe and colleagues (1998) performed an open-label study of daily azithromycin in children with CF in the UK, noting a modest improvement in spirometry with azithromycin therapy. The first well-constructed clinical trial of azithromycin in CF was reported by Wolter and colleagues (2002). Sixty CF patients (mean age 27.9 years) were randomly assigned in a double-blind fashion to 250 mg azithromycin daily or placebo for 3 months. A modest improvement favoring the macrolide was noted in spirometry, the requirement for intravenous antibiotic treatment for acute exacerbations, and quality of life. Equi and colleagues (2002) performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of 41 CF patients (age range 8–18 years). Patients received daily azithromycin adjusted to body weight or placebo for 6 months. After a 2-month washout period, patients were crossed over to the alternative therapy for 6 months. A modest improvement in FEV1 was noted favoring azithromycin; however, there was no difference in FVC, FEF25–75, pulmonary exacerbation rate, antibiotic use, changes in exercise tolerance, quality of well-being, bacterial culture densities, or sputum levels of interleukin-8 and neutrophil elastase.

The largest trial of macrolide therapy in CF was completed by Saiman and colleagues (2003), who performed a multi-centered, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of 185 patients ≥6 years of age who were chronically infected with P. aeruginosa and had a percent predicted FEV1 ≥30. Patients were treated with weight-adjusted azithromycin dosage. After 24 weeks treatment, the percent predicted FEV1 improved in the azithromycin group (4.4%), whereas it declined in the placebo group (1.8%, p = 0.001). Furthermore, azithromycin-treated patients were less likely to experience an exacerbation than those treated with a placebo (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44–0.95, p = 0.03). Subsequent post-hoc analyses confirmed that the improvement in secondary endpoints was independent of the change in FEV1 (Saiman et al 2005).

The mechanism for this favorable macrolide effect remains controversial and is likely multifactorial (Martinez and Simon 2004). There is growing evidence that macrolides may be beneficial by directly altering P. aeruginosa biology (Jaffe and Bush 2001; Nguyen et al 2002; Wagner et al 2005). Suggested mechanisms include: (1) microbicidal effects on P. aeruginosa that are in stationary as opposed to exponential growth phase; (2) reduction in the elaboration of virulence factors; (3) alteration in biofilm formation; (4) decrease in bacterial adherence to epithelial cells; (5) inhibition of bacterial motility; and (6) providing a synergistic effect to other antibiotics (Martinez and Simon 2004). It is likely that beneficial anti-inflammatory effects also play a role (Table 1) (Jaffe and Bush 2001; Nguyen et al 2002; Martinez and Simon 2004).

Table 1.

Anti-inflammatory and bacterial virulence effects of macrolide antibiotics

Abbreviations: IL, GM-CSF, TNF-α, PMN.

Macrolides in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

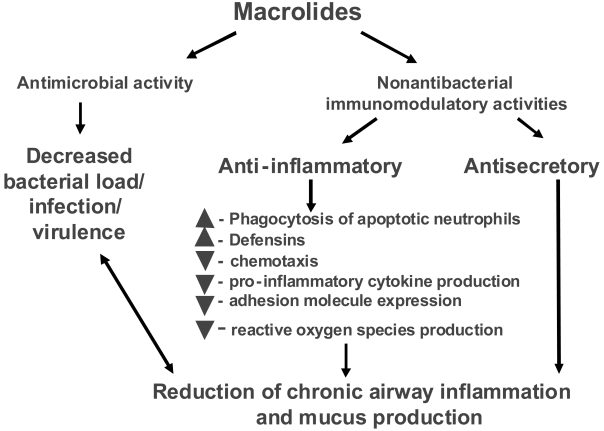

Taken together, the available data confirm that a macrolide can result in clinical improvement in patients with severe, chronic inflammatory lung diseases associated with frequent bacterial colonization and chronic infection. These data provide a rationale for expansion of the study of macrolide therapy to other, more common, inflammatory airway disorders, including COPD. Given the importance of inflammation and bacterial infection in the pathogenesis of COPD and its exacerbations, it is evident that macrolides may offer unique advantages as disease-modifying agents and that such an effect could be multifactorial (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Potential beneficial effects of macrolides in COPD patient.

This possibility is supported by three older published studies. First, a randomized trial contrasting moxifloxacin with clarithromycin in acute exacerbations confirmed clinical response to clarithromycin in 88.4% of patients, despite achieving bacteriologic eradication in only 48.8% (Wilson et al 1999). An immunomodulatory effect of the macrolide was suggested to explain this discrepant finding (Wilson 2005). Second, Suzuki and colleagues (2001) reported results of an open-label, prospective randomized trial of erythromycin therapy (200–400 mg/day) versus riboflavin (10 mg/day) for twelve months in COPD patients (FEV1 ~ 1.4 liters). During the course of therapy, the risk and frequency of experiencing a common cold using a predefined, standardized definition and subsequent acute exacerbations were prospectively evaluated. Table 2 enumerates the significant benefits noted with macrolide therapy. Although the results are intriguing, the unblinded data collection limits the strength of the conclusions in this study.

Table 2.

Effect of 12 months of erythromycin therapy on common colds and AECOPDs in patients with COPD

| Outcome | Treatment group

|

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (riboflavin) (n = 54) | Erythromycin (n = 55) | ||

| Total common colds, N | 245 | 67 | 0.0002 |

| Total number of exacerbations, N | 64 | 14 | <0.0001 |

| Mild/moderate exacerbations | 53 | 14 | 0.0087 |

| Severe | 11 | 0 | 0.0007 |

| Total patients with one or more exacerbations, N | 30 | 67 | <0.0001 |

| Mild/moderate | 20 | 6 | 0.0004 |

| Severe | 10 | 0 | 0.0004 |

Copyright © 2001. Reproduced with permission from Suzuki T, Yanai M, Yamaya M, et al. 2001. Erythromycin and common cold in COPD. Chest, 120:730–3.

Third, Gomez and colleagues (2000) identified 54 patients with a long history of chronic bronchitis (>10 years), a frequency more than five episodes per year, and at least two respiratory hospitalizations in the previous year. Patients were treated with azithromycin 500 mg daily for three days every 21 days from September through May and were compared to a similar, retrospective group of untreated COPD patients. Although there were no baseline differences between the treated patients and the control patients, over the course of follow-up macrolide treated patients experienced fewer exacerbations and hospitalizations per year (Table 3). Not unexpectedly, during exacerbations the azithromycin treated group experienced infection with S. pneumoniae (n = 21), P. aeruginosa (n = 6), and K. pneumoniae (n = 3). Interestingly, within the first 15 days of prophylactic treatment, 21 of these exacerbations were caused by S. pneumoniae isolates with diminished susceptibility to macrolides and penicillins. In the control group, the predominant isolates during an exacerbations included H. influenzae (n = 29) and S. pneumoniae (n = 9; two exhibiting diminished sensitivity to azithromycin). This study, although using a suboptimal, uncontrolled design, suggests that a beneficial response can be seen with chronic macrolide prophylaxis in high-risk COPD patients. The mechanism of improvement was not addressed, but could be related to the antibacterial activity (particularly with regards to H. influenzae).

Table 3.

Effect of azithromycin prophylactic therapy in COPD patients at high risk of AECOPD and treatment failure

| Outcome | Treatment group

|

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin (n = 54) | Control (n = 40) | ||

| Exacerbations/year | 187 | 249 | 30.0001 |

| Hospitalizations/year | 22 | 45 | 30.05 |

Copyright © 2000. Reproduced with permission from Gomez J, Baños V, Simarro E, et al. 2000. Estudio prospective y comparative (1994–1998) sobre la influencia del tratamiento corto profilactico con azitromicina en pacientes con EPOC evolucionada. Rev Esp Quimioterap, 13:379–83.

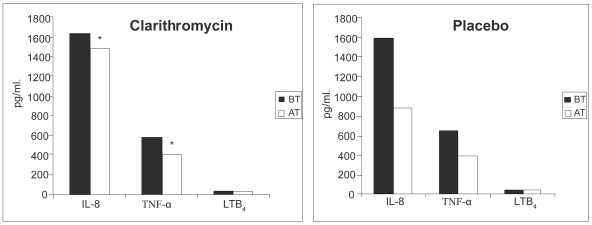

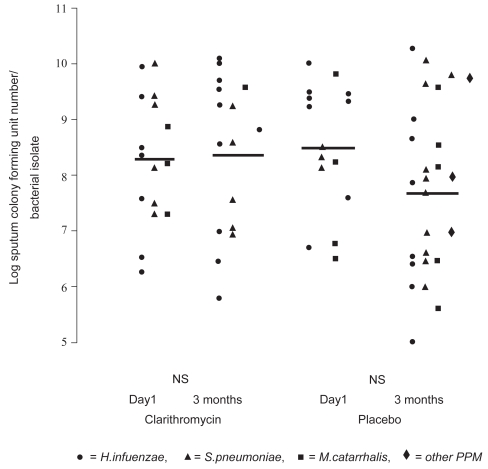

More recently, two groups have reported small controlled studies. Basyigit and colleagues (2004) randomized 30 stable male COPD patients (mean age ~69 yrs, FEV1~ 36% predicted) to clarithromycin (500 mg bid) or placebo for two weeks in addition to standardized bronchodilator therapy. Although no baseline differences were noted between the treatment groups, clarithromycin-treated patients experienced significantly improved sputum inflammatory markers (Figure 4), whereas physiologic studies did not change. The results of serum inflammatory markers were qualitatively similar in the two groups. In a second controlled study, 67 patients with moderate to severe COPD (mean age ~ 67 yrs, FEV1 ~43% pred) were randomized to three months of clarithromycin (500 mg of sustained release preparation daily) or placebo (Banerjee et al 2004). In contrast to the previous study, all patients were taking inhaled corticosteroids. Clarithromycin was associated with a significant improvement in the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) symptom score (10.2 units) and the SF-36 Physical Function Score (12.9 units) but no difference in overall SGRQ score, shuttle walk distance, spirometry or CRP levels. During the relatively short time of follow-up there were five total AECOPDs (3 in the clarithromycin and 2 in the placebo group). No difference was seen in quantitative sputum cultures obtained in the stable state (Figure 5). In contrast to the previous study, sputum IL-8, TNF-α, or LTB4 levels did not differ between clarithromycin versus placebo treatment, although there was a modest macrolide-associated improvement in sputum neutrophil differential and neutrophil chemotaxis (Banerjee et al 2004).

Figure 4.

Levels of induced-sputum inflammatory markers in clarithromycin- and placebo-treated COPD patients before and after treatment. AT, after treatment; BT, before treatment; IL-8, interleukin-8; LTB4, leukotriene B4; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α. *p < 0.05 before versus after treatment. Copyright © 2004. Reproduced with permission from Basyigit I, Yildiz F, Ozkara SK, et al. 2004. The effect of clarithromycin on inflammatory markers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: preliminary data. Ann Pharmacother, 38:783–92.

Figure 5.

The effect of clarithromycin and placebo on sputum colony forming units (Cfu) numbers/bacterial (PPM) isolate. Cfu numbers are logged. Weighted bars indicate the mean for the whole group. There was no statistically significant difference between pre- and post-therapy Cfu numbers for both clarithromycin and placebo groups. NS indicates not significant. Copyright © 2004. Reproduced with permission from Banerjee D, Honeybourne D, Khair OA. 2004. The effect of oral clarithromycin on bronchial airway inflammation in moderate-to-severe stable COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Treat Respir Med, 3:59–65.

Other investigators have proposed mechanistic rationale for improvement with chronic macrolide therapy in COPD patients. Tagaya and colleagues (2002) suggested that chronic bronchitis or bronchiectasis patients treated with clarithromycin (400 mg qd for seven days) experienced greater decrease in sputum volume than patients treated with a β-lactam. Parnham and colleagues (2005) treated 16 COPD patients (mean FEV1 1.8 liters) with azithromycin (500 mg daily) for three days and eight with placebo. Azithromycin resulted in an early transient increase in overall nitrite plus nitrate concentration, but later (days 11–18) decreases in total blood leukocyte count, serum CRP, IL-8- and oxidative burst of isolated blood granulocytes. No difference was noted in sputum inflammatory markers between azithromycin- treated and placebo-treated patients.

There is potential risk to chronic macrolide therapy in this patient population. Macrolide use may be associated with an increased risk of subsequent infection with macrolide nonsusceptible bacteria, particularly S. pneumoniae (Klugman and Lonks 2005; Vanderkooi et al 2005). An increase in macrolide-nonsusceptible S. pneumoniae has been reported with chronic erythromycin (Aberg et al 2001; Kasahara et al 2005), clarithromycin (Kasahara et al 2005) and azithromycin therapy (Gomez et al 2000; Aberg et al 2001). Similarly, these agents may be associated with gastrointestinal intolerance (Saiman et al 2003; Basyigit et al 2004; Cymbala et al 2005), cardiac toxicity (Iannini 2002; Milberg et al 2002), and ototoxicity (Haydon et al 1984; Swanson et al 1992; Wallace et al 1994). The frequency and severity of these toxicities varies with the agent, the dose and duration of therapy. These potential complications and the high prevalence of medical comorbitidies in COPD patients highlight the potential risk of chronic empiric macrolide therapy in this patient population.

Conclusions

Macrolide antibiotics have assumed an important role in the management of AECOPDs because of their broad-spectrum coverage and excellent safety profile. Increasingly, data are becoming available that macrolides have beneficial effects that are independent of their antibacterial activity. These potent anti-inflammatory effects may be particularly important in chronic inflammatory airway disorders. These latter actions may be of greatest benefit for selected patients with COPD, a disorder characterized by augmented pulmonary inflammation at baseline, frequent bacterial colonization/infection, and recurrent exacerbations of disease which further increase lung inflammation.

The role of chronic macrolide therapy in these patients requires additional study to better define a series of concerns, including:

What is the treatment-effect of chronic macrolide therapy in COPD patients treated maximally with conventional therapies?

Do macrolides attenuate baseline inflammation or do they prevent or attenuate AECOPD episodes?

Does the therapeutic effect reflect antimicrobial activity, an immunomodulatory effect, or both?

Does the therapeutic effect vary by host factors, including disease severity, presence of bronchiectasis, presence of baseline colonization with typical (including P. aeruginosa) or atypical pathogens (including C. pneumoniae), or the presence of comorbidity?

What is the toxicity of chronic therapy in COPD patients?

What is the risk-benefit of macrolide therapy in COPD patients?

Resolution of these vital questions will require additional, well-designed, placebo-controlled trials. To our knowledge three large studies are currently ongoing which should yield answers to all or most of these vital questions before widespread use of macrolide prophylaxis can be recommended in COPD patients.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH 2K24 HL004212, U10 HL074422 and HL082480 and HL56309 from the USPHS; and by Merit Review funding and a Research Enhancement Award Program (REAP) grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Aaron SD, Angel JB, Lunau M, et al. Granulocyte inflammatory markers and airway infection during acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:349–55. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2003122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberg JA, Wong MK, Flamm R, et al. Presence of macrolide resistance in respiratory flora of HIV-infected patients receiving either clarithromycin or azithromycin for Mycobacterium avium complex prophylaxis. HIV Clin Trials. 2001;2:453–9. doi: 10.1310/13GY-1LBY-355N-89HF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi T, Motojima S, Hirata A, et al. Eosinophil apoptosis caused by theophylline, glucocorticoids, and macrolides after stimulation with IL-5. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:S207–15. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agen C, Danesi R, Blandizzi C, et al. Macrolide antiboitics as antiinflammatory agents: roxithromycin in an unexpected role. Agents Actions. 1993;38:85–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02027218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agusti AGN. COPD, a multicomponent disease: implicationis for management. Respir Med. 2005;99:670–82. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira M, Kitatani F, Lee YS, et al. Diffuse panbronchiolitis: evaluation with high-resolution CT. Radiology. 1988;168:43–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.2.3393662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allegra L, Blasi F, de Bernardi B, et al. Antibiotic treatment and baseline severity or disease in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a re-evaluation of previously published data of a placebo-controlled randomized study. Pulm Pharmacol Therapeut. 2001;14:149–55. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allegra L, Blasi F, Diano PL, et al. Sputum color as a marker of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2005;99:742–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amayasu H, Yoshida S, Ebana S, et al. Clarithromycin suppresses bronchial hyperresponsiveness associated with eosinophilic inflammation in patients with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;84:594–8. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62409-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin K, Ekberg-Jansson A, Lofdahl CG, et al. Relationship between inflammatory cells and structural changes in the lungs of asymptomatic and never smokers: a biopsy study. Thorax. 2003;58:135–42. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson F, Borg S, Jansson SA, et al. The costs of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Respir Med. 2002;96:700–8. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrill J, Agusti C, De Celis R, et al. Bronchial inflammation and colonization in patients with clinically stable bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1628–32. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2105083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthonisen N, Manfreda J, Warren C, et al. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Int Med. 1987;106:196–204. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-2-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzueto A, Rizzo JA, Grossman RF. The infection-free interval: its use in evaluating antimicrobial treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Clin Inf Dis. 1999;28:1344–5. doi: 10.1086/517802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshiba K, Nagai A, Konno K. Erythromycin shortens neutrophil survival by accelerating apoptosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:872–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashitani J, Doutsu Y, Taniguchi H, et al. A case of diffuse panbronchiolitis relieved rapidly by the treatment of roxithromycin (Japanese) J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis. 1992;66:657–8. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.66.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach PB, Brown C, Gelfand SE, et al. Management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a summary and appraisal of published evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:600–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-7-200104030-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakri F, Brauer AL, Sethi S, et al. Systemic and mucosal antibody response to Moraxella catarrhalis after exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:632–40. doi: 10.1086/339174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balter MS, La Forge J, Low DE, et al. Canadian guidelines for the management of acute exacerbations of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Can Respir J. 2003;10(Suppl B):3B–32B. doi: 10.1155/2003/486285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi v, Jakubowycz M, Kinyon C, et al. Infectious exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with respiratory viruses and non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;10:69–75. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Honeybourne D, Khair OA. The effect of oral clarithromycin on bronchial airway inflammation in moderate-to-severe stable COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Treat Respir Med. 2004;3:59–65. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200403010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Khair OA, Honeybourne D. Impact of sputum bacteria on airway inflammation and health status in clinical stable COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:685–91. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00056804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker AF. Bronchiectasis. New Eng J Med. 2003;346:1383–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Shapiro SD, Pauwels RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:672–88. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basyigit I, Yildiz F, Ozkara SK, et al. The effect of clarithromycin on inflammatory markers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: preliminary data. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:783–92. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann U, Fischer JJ, Gudowius P, et al. Buccal adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis under long-term therapy with azithromycin. Infection. 2001;29:7–11. doi: 10.1007/s15010-001-0031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty CD, Grayston JT, Wang SP, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae, strain Twar, infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1408–10. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.6.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black PN, Blasi F, Jenkins CR, et al. Trial of roxithromycin in subjects with asthma and serological evidence of infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:536–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2011040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi F, Damato S, Cosentini R, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae and chronic bronchitis: association with severity and bacterial clearance following treatment. Thorax. 2002;57:672–6. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.8.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi F, Legnani D, Lombardo VM, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in acute exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi F, Ewig S, Torres A, et al. A review of guidelines for antibacterial use in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2006;19:361–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresser P, Out TA, van Alphen L, et al. Airway inflammation in nonobstructive and obstructive chronic bronchitis with chronic Haemophilus influenzae airway infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:947–52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9908103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramori G, Adcock I. Pharmacology of airway inflammation in asthma and COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2003;16:247–77. doi: 10.1016/S1094-5539(03)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin CL, Manzel LJ, Lehman EE, et al. Haemophilus influenzae from COPD patients with exacerbation induce more inflammation than colonizers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:85–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1687OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodosh S. Clinical significance of the infection-free interval in the management of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Chest. 2005;127:2231–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodosh S, McCarty J, Farkas S, et al. Randomized, double-blind study of ciprofloxacin and cefuroxime axetil for treatment of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. The Bronchitis Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:722–9. doi: 10.1086/514930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded interventionl trial. Lancet. 2004;363:600–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culic O, Erakovic V, Cepelak I, et al. Azithromycin modulates neutrophil function and circulating inflammatory mediators in healthy human subjects. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002 doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cymbala AA, Edmonds LC, Bauer MA, et al. The disease-modifying effects of twice-weekly oral azithromycin in patients with bronchiectasis. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:117–22. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G, Wilson R. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment of bronchiectasis with azithromycin. Thorax. 2004;59:540–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaki M, Okazaki H, Sunazuka T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of anti-inflammatory action of erythromycin in human bronchial epithelial cells: possible role in the signaling pathway that regulates nuclear factor-κB activation. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2004;48:1581–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1581-1585.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaki M, Takizawa H, Ohtoshi T, et al. Erythromycin suppresses nuclear factor-kB and activator protein-1 activation in human bronchial epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Res Com. 2000;267:124–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev D, Wallace E, Sankaran R, et al. Value of C-reactive protein measurements in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 1998;92:664–7. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalia JL, Rusznak C, Herdman MJ, et al. Effect of nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide on airway response of mild asthmatic patients to allergen inhalation. Lancet. 1994;344:1668–71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano A, Capelli A, Lusuardi M, et al. Decreased T lymphocyte infiltration in bronchial biopsies of subjects with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:893–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano A, Caramori G, Ricciardolo FLM, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an overview. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1156–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano A, Turato G, Maestrelli P, et al. Airflow limitation in chronic bronchitis is associated with T-lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration of the bronchial mucosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:629–32. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMango E, Ratner AJ, Bryan R, et al. Activation of NF-kappaB by adherent Pseudomonas aeruginosa in normal and cystic fibrosis respiratory epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2598–605. doi: 10.1172/JCI2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, et al. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57:847–52. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douwes J, Gibson P, Pekkanen J, et al. Non-eosinophilic asthma: importance and possible mechanisms. Thorax. 2002;57:643–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.7.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drost EM, Skwarski KM, Sauleda J, et al. Oxidative stress and airway inflammation in severe exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2005;60:293–300. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.027946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, et al. The most expensive medical conditions in America. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:105–11. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller J, Ede A, Schaberg T, et al. Infective exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Relation between bacteriologic etiology and lung function. Chest. 1998;113:1542–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.6.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Equi A, Balfour-Lynn IM, Bush A, et al. Long term azithromycin in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Lancet. 2002;360:978–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DJ, Cullinan P, Geddes DM, et al. Troleandomycin as an oral corticosteroid sparing agent in stable asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagon JY, Chastre J, Trouillet JL, et al. Characterization of distal bronchial microflora during acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis: use of the protected specimen brush technique in 54 mechanically ventilated patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:1004–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.5.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R, Fraser RS, Ghezzo H, et al. Alveolar inflammation and its relation to emphysema in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1666–72. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.5.7582312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fost DA, Leung DY, Martin RJ, et al. Inhibition of methylprednisolone elimination in the presence of clarithromycin therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:1031–5. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T, Kadota J, Kawakami K, et al. Long term effect of erythromycin therapy in patients with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Thorax. 1995;50:1246–52. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.12.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Yasuo M, Urushibata K, et al. Airway inflammation during stable and acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:640–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00047504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaga M, Bentley AM, Humbert M, et al. Increases in CD4+ T lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and interleukin 8 positive cells in the airways of patients with bronchiectasis. Thorax. 1998;53:685–91. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.8.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Tobias A, Anto JM, et al. Air pollution and mortality in a cohort of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:73–4. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey KW, Rubinstein I, Gotfried MH, et al. Long-term clarithromycin decreases prednisone requirements in elderly patients with prednisone-dependent asthma. Chest. 2000;118:1826–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.6.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis RJ, Iglewski BH. Azithromycin retards Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5842–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5842-5845.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez J, Baños V, Simarro E, et al. Estudio prospective y comparative (1994–1998) sobre la influencia del tratamiento corto profilactico con azitromicina en pacientes con EPOC evolucionada. Rev Esp Quimioterap. 2000;13:379–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompertz S, O’Brien C, Bayley DL, et al. Changes in bronchial inflammation during acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:1112–19. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.99114901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Inf Dis. 2001;33:757–62. doi: 10.1086/322627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SB. Viral respiratory infections in elderly patients and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2002;112 (6A):28S–32S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)01061-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumelli S, Corry DB, Song LZ, et al. An immune basis for lung parenchymal destruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. PLOS Med. 2004;1:75–83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulsvik A. The global burden and impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease worldwide. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2001;56:261–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gump DW, Phillips CA, Forsyth BR. Role of infections in chronic bronchitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;113:465–73. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.113.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert RJ, Isonaka S, George D, et al. Interpreting COPD prevalence estimamtes: what is the true burden of disease? Chest. 2003;123:1684–92. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern MT, Higashi MK, Bakst AW, et al. The economic impact of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis in the United States and Canada: A literature review. J Manages Care Pharm. 2003;9:353–9. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern MT, Stanford RH, Borker R. The burden of COPD in the USA: results from the Confronting COPD survey. Respir Med. 2003;97 (Suppl C):S81–9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin ME, Cote S, Laforge J, et al. Human metapneumo-virus infection in adults with community-acquired pneumonia and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:498–502. doi: 10.1086/431981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N, Kawabe T, Hara T, et al. Effect of erythromycin on matrix metalloproteinase-9 and cell migration. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;137:176–83. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2001.112726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon RC, Thelin JW, Davis WE. Erythromycin ototoxicity: analysis and conclusions based on 22 case reports. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:678–84. doi: 10.1177/019459988409200615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AT, Campbell EJ, Bayley DL, et al. Evidence for excessive bronchial inflammation during an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with a1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZ) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1968–75. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9904097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AT, Campbell EJ, Hill SL, et al. Association between airway bacterial load and markers of airway inflammation in patients with stable chronic bronchitis. Am J Med. 2000;109:288–95. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsuka T, Mukae H, Lliboshi H, et al. Increased concentration of human β-defensins in plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Thorax. 2003;58:425–30. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschmann JV. Do Bacteria cause exacerbations of COPD? Chest. 2000;118:193–203. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PL, Chan KN, Ip MSM, et al. The effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection on clinical parameters in steady-state bronchiectasis. Chest. 1998;114:1594–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.6.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Eng J Med. 2004;350:2645–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma H, Yamanaka A, Tanimoto S. Diffuse panbronchiolitis: a disease of the transitional zone of the lung. Chest. 1983;83:63–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.83.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst JR, Perera WR, Wilkinson TMA, et al. Systemic, upper and lower airway inflammation at exacerbation of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:71–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-704OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannini PB. Cardiotoxicity of macrolides, ketolides and fluoroquinolones that prolong the QTc interval. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2002;1:121–8. doi: 10.1517/14740338.1.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa Y, Ninomiya H, Koga H, et al. Erythromycin reduces neutrophils and neutrophil-derived elastolytic-like activity in the lower respiratory tract of bronchiolitis patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:1064–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimiya T, Takeoka K, Hiramatsu K, et al. The influence of azithromycin on the biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro. Chemotherapy. 1996;42:186–91. doi: 10.1159/000239440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura Y, Higashiyama Y, Tomono K, et al. Azithromycin exhibits bactericidal effects on Pseudomonas aeruginosa through interaction with the outer membrane. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2005;49:1377–80. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1377-1380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura Y, Yanagihara K, Mizuta Y, et al. Azithromycin inhibits MUC5AC production induced by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa auto-inducer N-(3-Oxododecanoyl) homoserine lactone in NCI-H292 cells. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2004;48:3457–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3457-3461.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamura K, Ohta N, Fukase S, et al. The effects of erythromycin on human peripheral neutrophil apoptosis. Rhinology. 2000;38:124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Okamoto R, Okubo T, et al. Comparative in-vitro activity of RP 59500 against clinical bacterial isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;30 (Suppl A):45–51. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.suppl_a.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu Y, Kadota J, Iwashita T, et al. Macrolide antibiotics induce apoptosis of human peripheral lymphocytes in vitro. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;24:247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa K, Suzuki T, Yamaya M, et al. Erythromycin increases bactericidal activity of surface liquid in human airways epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L565–73. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00316.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Ito M, Elliott WM, et al. Decreased histone deacetylase activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:1967–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A, Bush A. Anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides in lung disease. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2001;31:464–73. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A, Francis J, Rosenthal M, et al. Long-term azithromycin may improve lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 1998;351:420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Danziger LH. The macrolide anbiotics: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3045–53. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston SL. Overview of virus-induced airway disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:150–6. doi: 10.1513/pats.200502-018AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota J, Mukae H, Ishii H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of clarithromycin treatment in patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Resp Med. 2003;97:844–50. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota J, Mukae H, Tomono K, et al. High concentrations of β-chemokines in BAL fluid of patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Chest. 2001;120:602–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.2.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota J, Sakito O, Kohno S, et al. A mechanism of erythromycin treatment in patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:153–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota JI, Mizunoe S, Kishi K, et al. Antibiotic-induced apoptosis in human activated peripheral lymphocytes. Int J Antimicrob Agent. 2005;25:216–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoi H, Kurihara N, Fujiwara H, et al. The macrolide antibacterial roxithromycin reduces bronchial hyperresponsiveness and superoxide anion production by polymorphonuclear leukocytes in patients with asthma. J Asthma. 1995;32:191–7. doi: 10.3109/02770909509089507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai K, Asano K, Hisamitsu T, et al. Suppression of matrix metal-loproteinase production from nasal fibroblasts by macrolide antibiotics in vitro. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:671–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00057104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner RE, Anthonisen NR, Connett JE. Lower respiratory illnesses decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with promote FEV1 mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:358–64. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnak D, Bengsun S, Beder S, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Respir Med. 2001;95:811–16. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]