Abstract

The Gpg1 protein is a Gγ subunit mimic implicated in the G-protein glucose-signaling pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and its function is largely unknown. Here we report that Gpg1 blocks the maintenance of [PSI+], an aggregated prion form of the translation termination factor Sup35. Although the GPG1 gene is normally not expressed, over-expression of GPG1 inhibits propagation of not only [PSI+] but also [PIN+], [URE3] prions, and the toxic polyglutamine aggregate in S. cerevisiae. Over-expression of Gpg1 does not affect expression and activity of Hsp104, a protein-remodeling factor required for prion propagation, showing that Gpg1 does not target Hsp104 directly. Nevertheless, prion elimination by Gpg1 is weakened by over-expression of Hsp104. Importantly, Gpg1 protein is prone to self-aggregate and transiently colocalized with Sup35NM-prion aggregates when expressed in [PSI+] cells. Genetic selection and characterization of loss-of-activity gpg1 mutations revealed that multiple mutations on the hydrophobic one-side surface of predicted α-helices of the Gpg1 protein hampered the activity. Prion elimination by Gpg1 is unaffected in the gpa2Δ and gpb1Δ strains lacking the supposed physiological G-protein partners of Gpg1. These findings suggest a general inhibitory interaction of the Gpg1 protein with other transmissible and nontransmissible amyloids, resulting in prion elimination. Assuming the ability of Gpg1 to form G-protein heterotrimeric complexes, Gpg1 is likely to play a versatile function of reversing the prion state and modulating the G-protein signaling pathway.

Keywords: [PIN+], [PSI+], [URE3], Gpg1, yeast prion

Prions are infectious, self-propagating protein conformations, behaving as a “protein only” genetic element (1). The first characterized prion, mammalian PrPSc, is the pathogenic agent of a series of neurodegenerative disorders (2). Prion proteins have also been characterized in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as non-Mendelian inheritable elements, notably [PSI+], [URE3], [PIN+], and [SWI+] (3–5). [PSI+] (6) is a prion form (3, 7–9) of the polypeptide release factor Sup35 (eRF3) that is essential for terminating protein synthesis at stop codons (8, 10, 11). When Sup35 is in the [PSI+] state, ribosomes often fail to release polypeptides at stop codons, causing a non-Mendelian trait easily detectable by nonsense suppression (9, 12, 13).

The [PSI+]-mediated suppression of auxotrophic markers ade1–14 or ade2–1 (nonsense alleles) have been widely used to select for and study [PSI+] because nonsense suppression by [PSI+] can be easily detectable: [PSI+] allows cells to grow on synthetic medium lacking adenine and prevents the buildup of adenine metabolites that would cause [psi−] cells (soluble Sup35, no nonsense suppression) to turn red on rich media. Contrary to the ade1- or ade2-based approach to the [PSI+] state, the chromosomal ura3–197 (nonsense mutation) marker provided us with a powerful tool to select for the [psi−] (i.e., loss-of-[PSI+]) state, in which yeast cells become viable in the presence of 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) that is toxic to the [PSI+] cells (14, 15). By using this tool, we have isolated multiple chromosomal hsp104 mutations (14) that revert [PSI+], and an N-terminal deletion mutant of Rnq1, Rnq1Δ100, that eliminates [PSI+] when expressed from a multicopy plasmid (15). To our surprise, one [PSI+]-eliminating clone isolated in this selection encoded a G-protein γ subunit homolog, Gpg1, of S. cerevisiae (16).

S. cerevisiae possess two known G-protein-medicated signaling pathways to detect extracellular pheromones to activate an MAPK cascade, and to detect glucose to activate adenylate cyclase to produce a cAMP signal (17, 18). Typically, G proteins function as heterotrimeric complexes, composed of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits, which are activated when GTP binds to and replaces bound GDP on the Gα subunit to cause its dissociation from the Gβγ dimer. S. cerevisiae has two Gα proteins, Gpa1 and Gpa2, which have been shown to regulate mating and glucose/cAMP-signaling pathways, respectively (18). Gpg1 is a Gγ-subunit mimic found in a Gβγ-like dimer associated with Gpa2 (16). However, the role of Gpg1 in glucose signaling or any cellular regulation is largely unknown. In this study, we found that Gpg1 functions to eliminate known yeast prions or amyloids, suggesting a unique functional correlation between the G-protein signaling pathway and prion propagation in yeast.

Results

[PSI+] Elimination by Gpg1.

The [PSI+]-mediated suppression of ura3–197 (nonsense mutation) confers toxicity on 5-FOA, such that [PSI+] prion-containing cells are not viable on SGal + 5-FOA plates, whereas [psi−] cells are viable (14). By using suppression as a tool, we selected S. cerevisiae genes which, when over-expressed on a plasmid, results in [PSI+] elimination (15). Of these, one plasmid clone, pN5, contained GPG1 and one other protein-coding sequence (Fig. 1A). Subcloning segments of this construct [see supporting information (SI) Text] revealed that the GPG1 gene, expressed from the strong constitutive GPD promoter in plasmid pGPG1, is solely responsible for conferring 5-FOA resistance through [PSI+] elimination (see Fig. 1A).

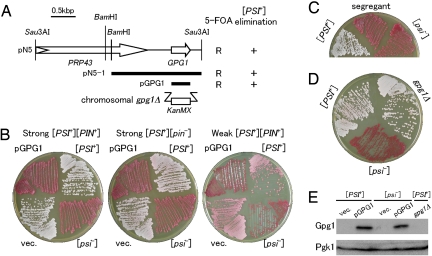

Fig. 1.

Over-expression of GPG1 eliminates the [PSI+] prion. (A) Schematic representation of genes cloned in plasmid pN5 and its derivatives. Open arrows identify protein-coding sequences. The bold bars indicate segments subcloned in constructing plasmids pN5–1 and pGPG1. The ability of these clones to confer 5-FOA resistance (R) and red color (i.e., [psi−]) (+) on a [PSI+] strain (NPK265; ade1–14 ura3–197) is indicated on the right. The gpg1Δ denotes a substitution of the KanMX marker for the chromosomal GPG1 gene. (B) [PSI+] elimination by the Gpg1-expressing plasmid, pGPG1. Strong or weak [PSI+] cells (ade1–14) were transformed with an empty vector (vec.: pRS413, single-copy plasmid with HIS3 marker) or pGPG1. Transformants were selected on SC-his after 3 days and regrown on YPD for 4 days to monitor colony color. [PSI+] and [psi−] control cells are also shown. Strains: Left, NPK265 (strong [PSI+] [PIN+]); Middle, NPK50 (strong [PSI+] [pin−]); Right, NPK197 (weak [PSI+] [pin−]). (C) Complete curing of [PSI+] after pGPG1 plasmid segregation. [PSI+] (NPK265 [PIN+]) cells were transformed with pGPG1 as shown in Fig. 1B (Left), and isolates that had spontaneously lost the plasmid were grown on YPD for 4 days. The “red” colonies remained red even in the absence of the pGPG1 plasmid. (D) Effect of chromosomal gpg1Δ on [PSI+] phenotype. Chromosomal GPG1 allele of NPK265 was nullified by substitution with the KanMX marker (strain BY4742 gpg1Δ) and colony color was monitored. (E) Gpg1 is visualized by immunoblotting. Equal amounts of total protein from whole cell lysates of NPK265 ([PSI+]) and its [psi−] derivative carrying plasmid pGPG1 or an empty vector (vec.), as well as from NPK563 (gpg1Δ), were separated by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Gpg1 antibody.

Plasmid pGPG1 also reverses the Ade+ phenotype of the NPK265 strain ([PSI+] ade1–14 nonsense allele), resulting in a buildup of adenine metabolites that cause cells to turn red on rich media (Fig. 1B Left). Ade+ (white)-to-Ade− (red) conversion by pGPG1 occurred in either a strong (white) or a weak (pink) [PSI+] strain, and in the presence or absence of [PIN+], the prion form of Rnq1 (19, 20) (see Fig. 1B). The [PIN+] independence of Gpg1-mediated [PSI+] elimination is distinct from Rnq1Δ100, which we previously identified to eliminate [PSI+] in the presence, but not the absence of [PIN+] (15). In these loss-of-[PSI+] transformants, complete curing of [PSI+] was confirmed in 3 independent pGPG1 segregants on nonselective media (Fig. 1C). In contrast to Gpg1 over-expression, the null gpg1Δ mutation did not affect [PSI+] (Fig. 1D). Western blotting using anti-Gpg1 antibody revealed that pGPG1-bearing transformants produced an excess of Gpg1 with a molecular mass of ≈15 kDa (Fig. 1E). We confirmed the absence of Gpg1 in the gpg1Δ strain and, under our growth conditions, Gpg1 wasn't detectable in the wild-type strain in the absence of pGPG1.

Expression of Gpg1 Eliminates [PIN+] and [URE3] Prions.

The above finding prompted us to investigate whether or not Gpg1 affects other yeast prions, [PIN+] and [URE3]. The [PIN+] prion was first examined by transforming the [PIN+] strain (NPK200 [psi−]) with pGPG1 or an empty vector, and the [PIN+] state was monitored by using a fusion of Rnq1 and green fluorescent protein (Rnq1-GFP) expressed from the CUP1 promoter. Rnq1-GFP formed foci with no diffuse fluorescence in the absence of pGPG1, whereas it was diffusely distributed in the presence of pGPG1 (Fig. 2A). In accordance with this finding, SDS-stable polymers of Rnq1 in [PIN+], a prion-specific aggregate detectable by semidenaturing detergent-agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE) (21), were eliminated on transformation with pGPG1 (Fig. 2B; note that the absence of Rnq1 polymers was confirmed after segregation of pGPG1 in 3 independent segregants). These results indicate that Gpg1 inhibits the maintenance of [PIN+].

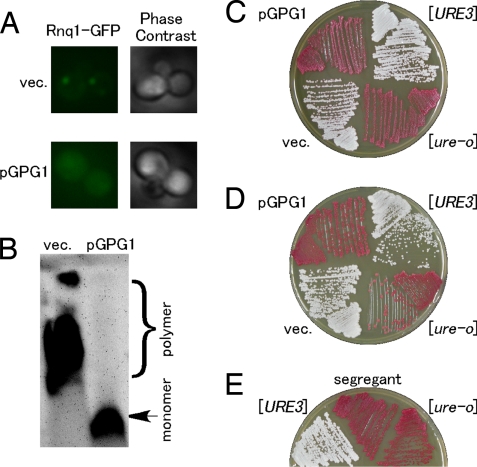

Fig. 2.

Elimination of [PIN+] and [URE3] prions by over-expression of Gpg1. (A) The [PIN+] strain (NPK200 [psi−]) was transformed with pGPG1 or an empty vector (vec.), and transformants were again transformed with pRS414CUP1p-Rnq1-GFP to visualize the [PIN+] or [pin−] state with Rnq1-GFP fusion protein. Rnq1-GFP expression under the control of the CUP1 promoter was induced by 50-μM CuSO4 for 6 h in liquid SC culture. Right and left panels show phase contrast image and fluorescent image of Rnq1-GFP, respectively. (B) Effect of pGPG1 on SDS-stable Rnq1 polymers in [PIN+] cells. NPK200 ([PIN+]) cells transformed with pGPG1 or an empty vector were harvested and lysed, and equal amounts of total protein from lysates were analyzed by SDD-AGE (1% SDS). Rnq1 was detected by immunoblotting using polyclonal rabbit anti-Rnq1 antibody. (C) [URE3] elimination by Gpg1 in the [pin−] state. The [URE3] [pin−] (NPK302) strain was transformed with pGPG1 or an empty vector, and the [URE3] state was monitored by the ADE2 color assay (23). In brief, the protein determinant of [URE3], Ure2, is a negative regulator of the transcription factor Gln-3 that activates the DAL5 promoter. The indicated reporter contains the ADE2 gene under the control of DAL5 promoter. A [ure-o] strain has active Ure2, which prevents ADE2 transcription and gives rise to red colonies on YPD. A [URE3] strain has inactive Ure2, which allows for ADE2 transcription and gives rise to white colonies on YPD. (D) [URE3] elimination by Gpg1 in the [PIN+] state with strain NPK304 ([URE3], [PIN+]). (E) Complete curing of [URE3] after segregation of the pGPG1 plasmid as per details described in Fig. 1C. Reproducibility was confirmed in 3 independent segregants.

[URE3] is the prion form of Ure2 (3), which is a regulator of nitrogen metabolism (22). The [URE3] prion was monitored by using test strains developed by Reed Wickner and colleagues (23), in which active Ure2 (i.e., in the [ure-o] state) negatively regulates the DAL5 promoter fusion to the ADE2 gene, giving red colonies on YPD, whereas the inactive Ure2 aggregate (i.e., in the [URE3] state) fails to turn off DAL5-ADE2 expression, giving white colonies on YPD. In this assay, [URE3] [pin−] (NPK302) and [URE3] [PIN+] (NPK304) cells turned red on transformation with pGPG1 (Fig. 2 C and D). The resulting red phenotype remained unchanged after segregation of pGPG1 (Fig. 2E), showing that Gpg1 completely eliminated the [URE3] prion.

Furthermore, over-expression of Gpg1 hampers toxic polyglutamine (polyQ) aggregates in [PIN+] cells in accordance with the previous notion that toxicity of polyQ is seen only in the presence of [PSI+] or [PIN+] prion (24, 25) (see SI Text and Fig. S1).

Effect of Gpg1 on Expression and Activity of Hsp104.

Hsp104, a protein-remodeling factor that disassembles denatured-protein aggregates (26), is required for the propagation of [PSI+], [URE3], and [PIN+] prions because it breaks up amyloid filaments to generate prion seeds for efficient prion transmission (9, 27, 28). To examine whether prion elimination by Gpg1 is mediated through disabled functionality of Hsp104 or not, we first monitored the cellular level of Hsp104 in NPK265 cells ([PSI+]) transformed with pGPG1. Western blotting using anti-Hsp104 antibody revealed that pGPG1 does not change the cellular abundance of Hsp104 (Fig. 3A). Then, the activity of Hsp104 in these transformants was examined by monitoring thermotolerance because Hsp104 is a heat-inducible protein required for thermotolerance and acts to resolubilize protein aggregates generated by severe stress, thereby allowing yeast to survive an otherwise lethal stress (29, 30). To measure thermotolerance, yeast cultures were exposed to 37 °C for 60 min as a pretreatment to induce the heat-shock response, then incubated at 50 °C for 20 min. The extent of survival was determined from 5-fold serial dilutions spotted to YPD+ade plates at 30 °C (Fig. 3B). In contrast to the hsp104Δ strain that shows no thermotolerance, pGPG1-bearing NPK265 strain showed no change in thermotolerance compared to the pGPG1-free strains. These results clearly demonstrate that prion elimination by Gpg1 is not caused by reduced functionality of Hsp104.

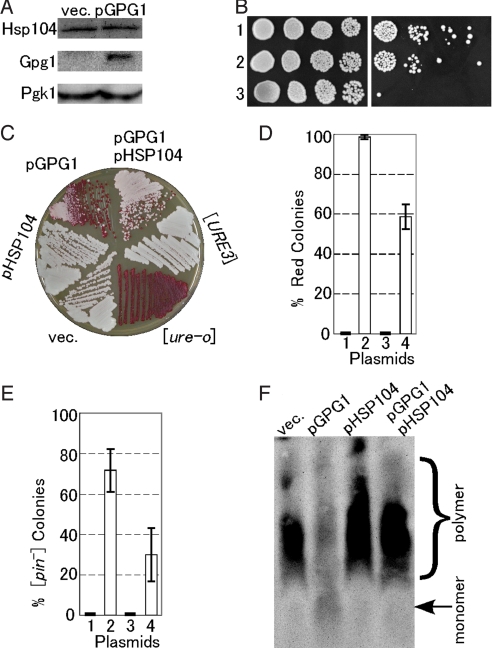

Fig. 3.

Effect of Gpg1 on expression and activity of Hsp104 and a compensatory effect of Hsp104 over-expression on prion elimination by Gpg1. (A) The cellular abundance of Hsp104. Equal amounts of total protein from whole cell lysates of NPK265 ([PSI+]) carrying plasmid pGPG1 or an empty vector (vec.) were separated by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Hsp104, -Gpg1, and -Pgk1 (control) antibodies. (B) Thermotolerance of Gpg1-overexpressing strain. Mid-log phase cultures of the indicated strains were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h to induce the heat-shock response and were then incubated for a further 20 min at 50 °C. The viability of heat-shocked cells (Right) was compared to untreated cells (Left) by 5-fold serial dilutions on YPD+ade agar. Cells were incubated at 30 °C for 2 days. Strains: 1, NPK265 carrying pGPG1; 2, NPK265 carrying an empty vector; 3, NPK339 (NPK265 derivative carrying hsp104Δ). (C) The DAL5-ADE2 reporter strain NPK302 ([URE3]) was transformed with pGPG1 and/or pHSP104, and the [URE3] state was monitored by colony color on YPD. (D) Semiquantitative estimation of the degree of [URE3] elimination. Strain NPK302 was transformed with the indicated plasmids. Fifty colonies from 3 independent transformations were grown on YPD plates; the frequency of red colonies was scored and the values are expressed with standard deviations. Plasmids: 1, empty vector; 2, pGPG1; 3, pHSP104; 4, pGPG1 plus pHSP104. (E) The [PIN+] strain (NPK200 [psi−]) transformants with pGPG1 and/or pHSP104 were transformed again with pRS414CUP1p-Rnq1-GFP, and the [PIN+] or [pin−] state was monitored by Rnq1-GFP fluorescent morphology as described in Fig. 2. Twenty transformant colonies, each from 3 independent transformations, were examined, scored for frequency of [pin−] colonies, and the values obtained are expressed with standard deviations. (F) The presence or absence of SDS-stable Rnq1 polymers in the above NPK200 transformants was analyzed by SDD-AGE as described in Fig. 2.

Prion-Eliminating Activity of Gpg1 Is Weakened by Over-Expression of Hsp104.

Although expression and activity of Hsp104 are not affected by Gpg1, it remains to be tested if the action of Hsp104 might affect Gpg1's activity. Hence, we examined the effect of co-expressing Hsp104 and Gpg1 on [URE3] and [PIN+] maintenance because Hsp104 over-expression is known to eliminate [PSI+] prion but not [URE3] or [PIN+] prion (31–33). As reported, Hsp104 over-expression did not affect the [URE3] state (i.e., white colonies) in the absence of pGPG1; however, it impaired Gpg1's ability to eliminate [URE3], leaving the majority of colonies white (Fig. 3C; semiquantitative estimation in Fig. 3D). A similar impairment of Gpg1 activity by Hsp104 was also observed in the [PIN+] strain, allowing the formation of Rnq1-GFP foci and SDS-stable Rnq1 polymers (Fig. 3 E and F). These findings suggest that Gpg1 and Hsp104 act oppositely at the same site, or in the same pathway during prion propagation. A similar compensatory effect of over-expressing Hsp104 was observed in [URE3] prion elimination by Rnq1Δ100, another prion-eliminating agent (Fig. S2).

Cellular Colocalization of Gpg1 and Sup35NM Aggregates.

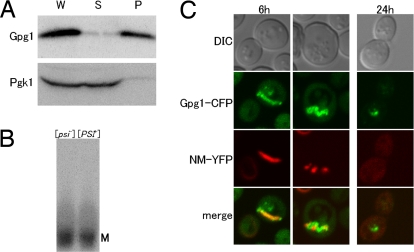

We have observed previously that Rnq1Δ100 is prone to self-aggregate and is occasionally colocalized with Sup35NM aggregates when expressed in [PSI+] cells (15). We found a similar protein tendency in Gpg1. When Gpg1 is expressed in a wild-type S. cerevisiae strain and its cell lysate is fractionated by a medium-speed (12,000 × g) centrifugation, Gpg1 is always found in pellet (Fig. 4A), showing that Gpg1 is prone to self-aggregate. However, the Gpg1 aggregate exhibits distinct properties compared with prion aggregates because it is SDS-unstable (as examined by the SDD-AGE analysis) (Fig. 4B) and is relatively diffuse compared with prion foci (as monitored by Gpg1-CFP fluorescence analysis) (shown below in Fig. 4C and Fig. S3). We investigated whether the Gpg1 aggregates colocalize with existing [PSI+] Sup35NM aggregates on coinduction of Gpg1-CFP and NM-YFP synthesis from the CUP1 promoter in [PSI+] strains. [Note that a direct fusion of Gpg1 to CFP leads to inactivation of Gpg1, and a peptide linker between Gpg1 and CFP is essential to maintain the activity (data not shown). Gpg1-CFP is also pelletable at 12,000 × g (Fig. S4).] Confocal fluorescence microscopy showed that although NM-YFP forms dot-like foci in the absence of Gpg1-CFP, it accumulates in the large, mostly peripherally located (but not filamentous) structures mostly colocalized with Gpg1-CFP aggregates 6 h after induction of Gpg1-CFP, and became disperse 24 h after the induction (see Fig. 4C and Fig. S3; note that a wider field image is presented in Fig. S3 and the indicated box-field image is presented in Fig. 4C). It is noteworthy that strand-like foci of NM-YFP appeared 6 h after induction of Gpg1-CFP (see Fig. 4C and Fig. S3), which are rarely seen in any experimental conditions except for wild-type Gpg1 coexpression. These findings are interpreted as indicating a direct transient association of Sup35NM with Gpg1 aggregates during [PSI+] elimination.

Fig. 4.

Gpg1 aggregation and transient colocalization of Sup35NM with Gpg1 aggregates. (A) Self-aggregation of Gpg1 protein. Cell lysates of strain NPK564 transformed with pGPG1 were fractionated by centrifugation at 12,000 × g, and each fraction was separated by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Gpg1 and anti-Pgk1 antibodies. Fractions: P, pellet; S, supernatant; W, whole lysate. (B) SDS sensitivity of Gpg1 aggregates. NPK564 ([psi−]) and NPK265 ([PSI+]) cells transformed with pGPG1 were harvested and lysed, and equal amounts of total protein from lysates were analyzed by SDD-AGE (1% SDS). Gpg1 was detected by immunoblotting using polyclonal rabbit anti-Gpg1 antibody. M denotes a monomer fraction. (C) The [PSI+] strain (NPK265) was transformed with pRS424CUP1p-Gpg1-CFP and pRS413CUP1p-NM-YFP. These transformants were grown to early log-phase and supplemented with 50-μM CuSO4, followed by growth for 6 and 24 h. Shown are differential interference contrast images and confocal fluorescent images of CFP (green), YFP (red), and their merge in which colocalization of Gpg1-CFP and NM-YFP is shown by yellow. NM-YFP coalesced into strand-like fluorescent foci at 6 h after induction and was diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm at 24 h after induction.

Loss-of-Activity gpg1 Mutations and Protein Architecture.

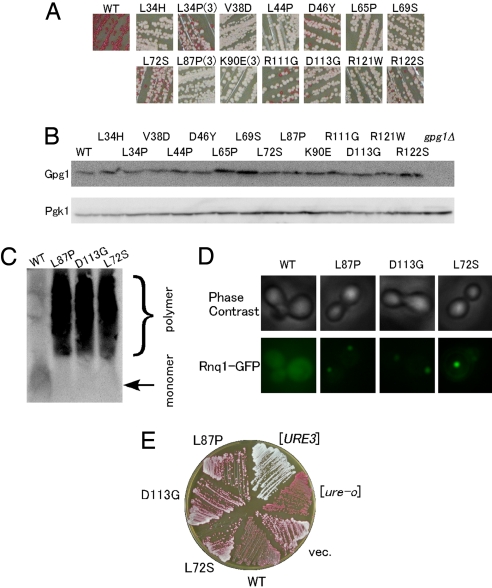

To prove the direct involvement of Gpg1 and to assess the protein domain or residues crucial for prion elimination, loss-of-activity mutants of Gpg1 were isolated from colonies that remained white after transformation of strain NPK265 ([PSI+] ade1–14; white) with a PCR mutated GPG1 plasmid (see Methods). Plasmid DNAs that gave a reproducible phenotype were characterized by DNA sequencing. Of the numerous independent isolates examined, we identified 14 distinct amino acid substitutions that impaired the ability of Gpg1 to eliminate [PSI+] (Fig. 5A). There was phenotypic diversity in the identified gpg1 mutants, with some mutants giving rise to all white colonies whereas others gave rise to a mixture of white and red colonies (see Fig. 5A). The abundance of mutant Gpg1 proteins in these transformants did not change appreciably (Fig. 5B), indicating that the loss of [PSI+] elimination ability is caused by the loss of protein activity, and not stability. All of these gpg1 mutants also hampered the ability to eliminate [PIN+] and [URE3] prions, to varying extents, as examined by the SDD-AGE analysis, GFP fluorescence, and colony-color assay (Fig. 5 C–E; data summarized in Table S1).

Fig. 5.

Loss-of-activity gpg1 mutants. (A) Color assay to determine the [PSI+]-eliminating ability of mutant Gpg1 proteins. NPK265 strain ([PSI+] ade1–14) was transformed with pGPG1 plasmids containing the indicated mutations, and transformants' color was monitored on YPD plates. Mutations isolated multiple times are marked by parentheses with the number of independent isolates, whereas the others are single isolates. WT denotes wild-type Gpg1. (B) The protein abundance of mutant Gpg1s. Lysates from the above transformants were examined by Western blotting as described in Fig. 1E. (C) SDD-AGE assay of [PIN+]-eliminating ability of mutant Gpg1 proteins. The formation of Rnq1 polymers in NPK200 ([PIN+]) transformants with pGPG1 plasmids carrying wild-type and the indicated gpg1 mutations was examined by SDD-AGE. (D) The same set of gpg1 mutant transformants as in (C) was transformed with pRS414CUP1p-Rnq1-GFP, and the [PIN+] state was examined by Rnq1-GFP fluorescence assay. (E) DAL5-ADE2-based color assay of [URE3]-eliminating activity of the gpg1 mutants. Experiments were performed as in Fig. 2D.

Three representative mutants, L72S, L87P, and D113G, were examined further. Centrifugation assay indicated that these Gpg1s are pelletable at 12,000 × g, similar to wild-type Gpg1 (Fig. S5A). Confocal microscopy showed that [PSI+] NM-YFP aggregates underwent a morphological change from dot-like foci to slightly diffuse foci 6 h after induction of mutant Gpg1-CFPs, and NM-YFP and mutant Gpg1-CFPs are mostly colocalized (Fig. S5B). NM-YFP foci, however, did not become fully disperse 24 h after the induction, unlike the wild-type Gpg1 (data not shown). These findings suggest that the disabled Gpg1 proteins could interact, directly or indirectly, with [PSI+] Sup35NM aggregates and remain a residual activity to trigger prion elimination only prematurely.

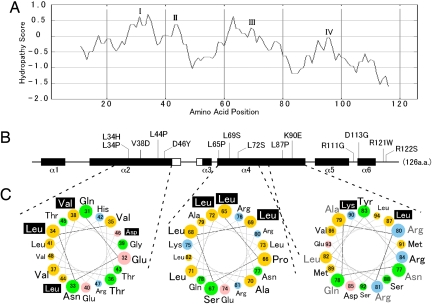

The hydropathy profile of Gpg1 reveals the protein to contain 4 hydrophobic regions, I through IV, with many loss-of-activity substitutions localized to the relatively hydrophobic regions (Fig. 6 A and B). Secondary protein structure predictions show that Gpg1 is rich in α-helical structures, α1 through α6, and 10 of 14 substitutions are mapped to 2 major α helices, α2 and α4 (see Fig. 6B). These two α helices are amphiphilic in nature, with asymmetric distribution of nonpolar and hydrophilic amino acid residues around the helices, as shown in the helical wheel projection (Fig. 6C). Importantly, most of the mutations are localized to one side of the hydrophobic surfaces of α2 and α4 (see Fig. 6C), suggesting that the hydrophobic surfaces could be involved in protein-protein interactions and that the loss-of-activity substitutions would disable these protein interactions.

Fig. 6.

Protein architecture of Gpg1 and structural localization of loss-of-activity gpg1 mutations. (A) The hydropathy profile of Gpg1 generated by (http://www-personal.umich.edu/∼ino/blast.html). Representative hydrophobic regions are named I–IV. (B) Secondary protein structure prediction generated from the PSIPRED Protein Structure Prediction Server (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred) (34). Open and closed boxes indicated β-sheets and α-helices (referred to α-1 through α-6), respectively, and bars indicate coils. Positions of amino acid substitutions are shown. Numbers represent the amino acid positions from the first Met codon. Note that the amino acid positions are shown in the same scale in (A) and (B) for comparison. (C) Helical wheel projection of residues in α-2 and α-4 of Gpg1. Residues 31–48 (helix α-2) and 65–94 (helix α-4) of Gpg1 are shown in a helical wheel projection created with the WheelApp applet (http://cti.itc.Virginia.EDU/∼cmg/Demo/wheel/wheelApp.html). Residues 65–94 (helix α-4) are split into 2 wheels in the same orientation: Note that residues 77–82 (gray, Right) are duplicated in both wheel projections in the same position. Acidic residues are shown in pink, basic residues in blue, neutral (uncharged polar) amino acids in green, and hydrophobic (nonpolar) amino acids in yellow. Loss-of-activity residues are designated with white text shadowed in black.

Effect of G-Protein α and β Subunit Deletions on Gpg1 Activity.

To clarify whether Gpg1's partners in the glucose-signaling pathway (i.e., G-protein α and β subunits) are involved in prion elimination by Gpg1, we constructed chromosomal Gα and Gβ gene deletions, gpa2Δ and gpb1Δ, respectively, and examined their effects by genetic manipulations. First, we failed to find any significant change in the frequency of [PSI+] maintenance in gpa2Δ and gpb1Δ deficient strains (data not shown). Second, Gpg1's ability to eliminate [PSI+] was unaffected in gpa2Δ and gpb1Δ strains (Fig. S6). Although the gpb2Δ construct remains to be tested, it seems unlikely that the G-protein complex containing Gpg1 plays a direct role in prion elimination.

Discussion

In this study, we isolated a unique general antagonist of prion propagation, Gpg1, by using the ura3–197 (nonsense mutation)-based selection (14). Over-expression of Gpg1 eliminates known S. cerevisiae prions, [PSI+], [URE3], and [PIN+], as well as the toxic polyglutamine aggregate. The prion-eliminating ability of Gpg1 differs from that of Rnq1Δ100, another prion-eliminating agent identified in the same selection method (15), at least in two aspects. Firstly, Gpg1 can eliminate [PIN+], whereas Rnq1Δ100 cannot. Secondly, the prion elimination by Gpg1 occurs in both [PIN+] and [pin−] cells, whereas Rnq1Δ100 requires the presence of [PIN+] to eliminate [PSI+] and [URE3] prions. The shared as well as distinct properties in prion elimination by Gpg1 and Rnq1Δ100 might reflect the mechanistic resemblance and difference.

It is highly surprising that a component of the G-protein signaling pathway, Gpg1, plays a negative role in the prion propagation in yeast. Gpg1 is a small, 126-residue protein, and has been isolated as a Gγ subunit mimic that forms a Gβγ-like dimer with Gpb1 or Gpb2, a Gβ subunit mimic, and binds to Gpa2, the Gα subunit responsible for glucose signaling (16). However, the sequence or architectural resemblance between Gpg1 and the authentic Gγ subunits is relatively low. It is speculated that Gpa2 doses not appear to have an authentic Gβγ partner and that a Gβγ-like dimer, Gpb1/2●Gpg1, might act as a pseudostructural inhibitor of the glucose/cAMP signaling pathway to negatively regulate haploid inactive, filamentous growth (18).

We might speculate two possible scenarios to explain the inhibition of prion propagation by Gpg1. A straightforward explanation is that Gpg1 binds to the growing tip of a prion aggregate and blocks its rapid growth, leading to its destabilization and loss (“capping” model; ref. 35). This is consistent with the finding that Gpg1 is prone to self-aggregate and is able to colocalize with the Sup35NM aggregate in [PSI+] cells until the dispersion of [PSI+] foci (see Fig. 4). The protein architecture analysis reveals that Gpg1 is largely hydrophobic and possesses two α helices, α2 and α4, of amphiphilic nature (see Fig. 6). Hydrophobic amino acids are clustered on one side of the α helices and are affected by multiple loss-of activity gpg1 mutations. Therefore, we would speculate that the hydrophobic surfaces of α2 and α4 are involved in a crucial interaction with prion amyloids or some cofactors, which might be impaired by gpg1 mutations. Confocal microscopy observation that disabled Gpg1s are colocalized with [PSI+] Sup35NM aggregates (see Fig. S5) suggests it less likely that the presumed hydrophobic surface serves as a direct interaction site for prion amyloids. The alternative explanation is that over-expression of Gpg1 affects the S. cerevisiae glucose/cAMP signaling pathway and exerts an inhibitory effect on the propagation of yeast prions indirectly by turning on or off downstream effectors. Although this possibility cannot be ruled out completely, we assume this unlikely because gpa2Δ and gpb1Δ null mutations did not affect prion maintenance and Gpg1-induced prion elimination.

The GPG1 gene appears to be normally silent (see Fig. 1E). This situation is favorable for the prion propagation as well as for glucose/cAMP signaling because Gpg1 is a potent inhibitor of (probably) both processes. Therefore, if a physiological or environmental condition exists that induces GPG1 expression, it might operate as a unique regulatory system to turn off prion propagation and change G protein signaling in S. cerevisiae.

Methods

Strains, Plasmids, and Manipulations.

S. cerevisiae strains used in the present study are listed in Table S2. Media and other manipulations, including fluorescence microscopy, colony color-based prion assay, and protein analysis are as described previously except that anti-Gpg1 rabbit polyclonal antibody was prepared against full-length Gpg1 in the present study (15). To isolate multicopy-plasmid-based antagonists of [PSI+], S. cerevisiae [PSI+] strain (NPK265; MATa ade1–14 leu2 ura3–197 his3 trp1) was transformed with a yeast genomic library cloned into pRS423, and the resulting His+ transformants were screened for 5-FOA resistance on SGal-his + 5-FOA plates (i.e., Ura− phenotype) and red colony color on YPD plates (Ade− phenotype), as described previously (15). pN5 (see Fig. 1A) is one such plasmid with a reproducible phenotype to eliminate [PSI+]. Plasmids used are pRS400 series vectors (Stratagene) and their expression derivatives (designated after the promoter, such as pRS423GPDp or pRS423CUP1p) containing the GPD or CUP1 promoter and the CYC1 terminator for expression of exogenous sequences (15). Details of plasmid and strain construction and other manipulations are described in the SI Text.

Isolation of Loss-of-Activity gpg1 Mutations.

The 0.7-kb fragment containing the GPG1 coding sequence, 5′-flanking (GPD promoter) and 3′-flanking (CYC1 terminator) sequences was amplified by error-prone PCR in vitro, and cotransformed into the NPK265 ([PSI+] ade1–14; white) strain with a linearized, BamHI-XhoI, plasmid pRS426 (multicopy 2μ, URA3) carrying the GPD promoter and CYC1 terminator. The mutagenized gpg1 sequences were inserted in vivo into the vector sequence at the GPD promoter and the CYC1 terminator sequences by homologous recombination. The resulting Ura+ transformants were selected on SC-ura plates and replica-plated onto YPD plates to screen for white (i.e., [PSI+]) colonies. Plasmids that gave a reproducible phenotype were characterized by DNA sequencing and genetic studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Reed B. Wickner (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), Koichi Ito (University of Tokyo), and Michael Y. Sherman (Boston University, Boston, MA) for the gift of strains and plasmids; and Colin G. Crist, Koreaki Ito, and Charles Yanofsky for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable comments. This work was supported in part by grants from The Ministry of Education, Sports, Culture, Science and Technology of Japan and the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy Control Project of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0808383106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Early evidence that a protease-resistant protein is an active component of the infectious prion. Cell. 2004;116:S109. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wickner RB. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: Evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sondheimer N, Lindquist S. Rnq1: An epigenetic modifier of protein function in yeast. Mol Cell. 2000;5:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du Z, Park KW, Yu H, Fan Q, Li L. Newly identified prion linked to the chromatin-remodeling factor Swi1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Genet. 2008;40:460–465. doi: 10.1038/ng.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox BS. ψ, a cytoplasmic suppressor of super-suppressor in yeast. Heredity. 1965;20:505–521. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ter-Avanesyan MD, Dagkesamanskaya AR, Kushnirov VV, Smirnov VN. The SUP35 omnipotent suppressor gene is involved in the maintenance of the non-Mendelian determinant [psi+] in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1994;137:671–676. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhouravleva G, et al. Termination of translation in eukaryotes is governed by two interacting polypeptide chain release factors, eRF1 and eRF3. EMBO J. 1995;14:4065–4072. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paushkin SV, Kushnirov VV, Smirnov VN, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Propagation of the yeast prion-like [psi+] determinant is mediated by oligomerization of the SUP35-encoded polypeptide chain release factor. EMBO J. 1996;15:3127–3134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stansfield I, et al. The products of the SUP45 (eRF1) and SUP35 genes interact to mediate translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:4365–4373. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrenberg M, Hauryliuk V, Crist CG, Nakamura Y. Translation Termination, Prion [PSI+], and Ribosome Recycling. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2007. pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebman SW, Sherman F. Extrachromosomal ψ+ determinant suppresses nonsense mutations in yeast. J Bacteriol. 1979;139:1068–1071. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.3.1068-1071.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patino MM, Liu JJ, Glover JR, Lindquist S. Support for the prion hypothesis for inheritance of a phenotypic trait in yeast. Science. 1996;273:622–626. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurahashi H, Nakamura Y. Channel mutations in Hsp104 hexamer distinctively affect thermotolerance and prion-specific propagation. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1669–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurahashi H, Ishiwata M, Shibata S, Nakamura Y. A regulatory role of the Rnq1 nonprion domain for prion propagation and polyglutamine aggregates. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3313–3323. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01900-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harashima T, Heitman J. The Galpha protein Gpa2 controls yeast differentiation by interacting with kelch repeat proteins that mimic Gbeta subunits. Mol Cell. 2002;10:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sprang SR. G protein mechanisms: Insights from structural analysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:639–678. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman CS. Except in every detail: Comparing and contrasting G-protein signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:495. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.3.495-503.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: The story of [PIN+] Cell. 2001;106:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osherovich LZ, Weissman JS. Multiple Gln/Asn-rich prion domains confer susceptibility to induction of the yeast [PSI+] prion. Cell. 2001;106:183–194. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liebman SW, Bagriantsev SN, Derkatch IL. Biochemical and genetic methods for characterization of [PIN+] prions in yeast. Methods. 2006;39:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magasanik B, Kaiser CA. Nitrogen regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 2002;290:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00558-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brachmann A, Baxa U, Wickner RB. Prion generation in vitro: Amyloid of Ure2p is infectious. EMBO J. 2005;24:3082–3092. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meriin AB, et al. Huntington toxicity in yeast model depends on polyglutamine aggregation mediated by a prion-like protein Rnq1. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:997–1004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gokhale KC, Newnam GP, Sherman MY, Chernoff YO. Modulation of prion-dependent polyglutamine aggregation and toxicity by chaperone proteins in the yeast model. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22809–22818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogura T, Wilkinson AJ. AAA+ superfamily ATPases: Common structure-diverse function. Genes Cells. 2001;6:575–597. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung G, Jones G, Masison DC. Amino acid residue 184 of yeast Hsp104 chaperone is critical for prion-curing by guanidine, prion propagation, and thermotolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9936–9941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152333299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ness F, Ferreira P, Cox BS, Tuite MF. Guanidine hydrochloride inhibits the generation of prion “seeds” but not prion protein aggregation in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5593–5605. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5593-5605.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez Y, Lindquist SL. HSP104 required for induced thermotolerance. Science. 1990;248:1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.2188365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsell DA, Kowal AS, Singer MA, Lindquist S. Protein disaggregation mediated by heat-shock protein Hsp104. Nature. 1994;372:475–478. doi: 10.1038/372475a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [psi+] Science. 1995;268:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Zhou P, Chernoff YO, Liebman SW. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;147:507–519. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moriyama H, Edskes HK, Wickner RB. [URE3] prion propagation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Requirement for chaperone Hsp104 and curing by overexpressed chaperone Ydj1p. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8916–8922. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8916-8922.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DT. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derkatch IL, Liebman SW. Prion–prion interactions. Prion. 2007;1:161–169. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.3.4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.