Abstract

Objective

To develop and implement learning activities within an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) to improve students' cultural competence.

Design

During their AAPE at Community Access Pharmacy, students participated in topic discussions with faculty members, used interpreters to interview Hispanic patients, visited a Mexican grocery store, evaluated nontraditional medicine practices in the Hispanic community, and served as part of a patient care team at a homeless shelter and an HIV/AIDS clinic. The students reflected on these activities in daily logs and completed a final evaluation of their experiences.

Assessment

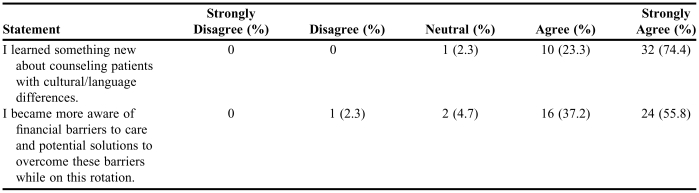

Forty-three students completed the rotation from 2004-2007. Almost all learned something new about counseling patients with cultural/language differences (98%) and became more aware of financial barriers to health care and potential solutions to overcome them (93%). Students' reflections were positive and showed progression toward cultural competence.

Conclusion

A culturally diverse patient population provided opportunities for APPE students to develop the skills necessary to become culturally competent pharmacists. Future work should focus on potential evaluation tools to assess curricular cultural competency outcomes in APPE's.

Keywords: experiential education, cultural competency, diversity

INTRODUCTION

Teaching cultural competence is vital to transform pharmacy students into future practitioners who can provide true pharmacy care to an increasingly diverse patient population. Cultural competence is defined by the Office of Minority Health as “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables effective work in cross-cultural situations.”1 To optimize patient outcomes, pharmacists must understand the variety of factors that help shape a patient's healthcare experience. A source of the health disparities that exist in culturally diverse populations may come from a lack of cultural competence among health practitioners. The Institute of Medicine's report, “Unequal Treatment,” underscores the importance of incorporating cross-cultural curricula to educate future health care providers about methods to address these disparities.2

The demographic characteristics of the US population are changing rapidly, with Hispanics representing the fastest growing ethnic group. According to the US Census, the Hispanic population is expected to increase by 34.1% between 2000-2010, while the non-Hispanic white population is expected to be the slowest growing segment of the population over the next 50 years.3 These changes have many important implications for the healthcare system. Pharmacists must understand that culture is not simply defined by ethnicity or race. Culture can be influenced, in varying degrees, by factors such as language, customs, values, beliefs, religion, and social groups, irrespective of ethnicity or race.1 Although the ethnic dimensions of culture receive the most attention, pharmacists should have the ability to consider each of these characteristics when interacting with patients and developing drug therapy plans.

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) adopted guidelines in 2006 that require pharmacy programs to prepare students to practice in a culturally competent manner.4 The ACPE's Standard 12 states that providing patient care entails “taking into account relevant legal, ethical, social, cultural, economic, and professional issues…that may impact therapeutic outcomes.” Pharmacy colleges are looking at ways to weave the thread of cultural competence training into their curricula. A study by Onyoni and Ives5 evaluated trends in adding curricular content related to cultural competency by surveying curriculum committee chairs and student leaders. They found that 94% (n = 46) of respondents felt it necessary to add cultural competency topics to required courses. Of those colleges already offering cultural competency training in their curricula, the most common methods were through didactic (51%) or case-based (26%) lessons. Experiential education as a method of teaching cultural competency only occurred in 18% (n = 9) of programs surveyed.

The framework and conceptual understanding of culturally diverse interactions should be in place before students are given the opportunity to learn from individual patients in a pharmacy practice setting. Pharmacy courses and training sessions have been described previously by Evans and Assemi.6,7 These types of courses play an important role in educating pharmacy students. Experiential education, including advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs), should serve as a bridge for translating these concepts into practice through real patient encounters. As with other topics in the curriculum, it is necessary to create opportunities for students to learn in APPEs which enhance their understanding of classroom material. It is essential to allow students time to care for patients whose culture is different from their own. Quist and Law developed an Agenda for Cultural Competency Using Literature and Evidence (ACCULTURE)8 which outlines 2 primary goals for pharmacists: (1) understand a patient's current situation, and (2) communicate back to the patient to ensure patient adherence to prescription regimens and counseling. Practicing these skills with diverse patients during APPEs is necessary to help students develop into culturally competent pharmacists.

The APPE at Community Access Pharmacy encourages students to interact with diverse patient populations. Two of the primary learning objectives for this APPE are to develop culturally sensitive communication strategies and to improve understanding of methods to increase health care access for disadvantaged patients. Activities are designed to support achievement of rotation objectives with an ultimate goal of progression towards cultural competency.

DESIGN

In the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program at the Drake University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences students learn about cultural competency throughout the professional curriculum. The Pharmacy Skills and Applications (PSA) sequence builds on 8 core areas: professionalism, communications, clinical reasoning, cultural competence, drug information, distribution systems and processes, calculations, and systems management. The course, which is required each semester, is comprised of a 1-hour lecture and a 2-hour laboratory, along with an experiential component. In the first year, students learn how to define cultural competence. They also discuss recognition of cultural differences and perform a cultural competency self-assessment. The second year focuses on incorporating cultural competence into communication, including patients who do not speak English. The third year of the PSA curriculum teaches students to use cultural understanding to identify drug therapy problems and improve patient counseling. Experiential learning offers opportunities for students to practice what they have learned in class. The PSA sequence is comprised of both required and elective experiential learning, including a required diversity service-learning project.

Following completion of their third year in the professional pharmacy program, Drake pharmacy students completed eight 5-week APPEs. The APPE at Community Access Pharmacy (CAP) allowed students exposure to a diverse patient population. As a 340B pharmacy, CAP served uninsured and underinsured patients in Des Moines, Iowa, a significant percentage of which are Hispanic. The pharmacy also filled prescriptions for patients positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who were seen at a Ryan White clinic, as well as indigent patients, some of whom were homeless or lived in shelters. Clinical services, including diabetes education and smoking cessation, were provided to these patients at the pharmacy by a faculty member from Drake University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences. APPE students played an integral role in the provision of clinical services at CAP. Two students were assigned to the pharmacy during each APPE block. Activities were coordinated by the faculty member throughout the APPE, allowing students to develop knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards becoming culturally competent.

Topic discussions were held on a regular basis throughout the community pharmacy APPE. While some of the topics were clinical in nature, such as asthma, diabetes, and hypertension, others focused on an understanding of what it means to be a culturally competent pharmacist. Two faculty members (the CAP pharmacist and the pharmacist at a nearby free clinic) and their students joined together for the cultural competency discussions. Specific topics were initiated by the faculty members and students actively participated by sharing personal comments and professional experiences. To prepare for the discussions, students were required to read the American Pharmacists Association's (APhA) Working with Hispanic Populations during the first week of the rotation.9 This article provided the student with basic information about the Hispanic community, cultural considerations, traditional healing beliefs, interviewing techniques, and potential language barriers. Students were asked about their impressions of the reading and what implications could arise from cultural differences between patients and pharmacists. Throughout the discussion, an emphasis was placed on the importance of avoiding stereotypes and generalizations and seeing patients as individuals.

Students were provided models to follow in eliciting patients' health beliefs. The way a patient views his or her own disease or condition has a large impact on determining the most appropriate healthcare intervention. Kleinman developed a series of 8 questions that provide guidance on eliciting health beliefs.10 These questions encourage patients to disclose information so healthcare providers can work with them to achieve a common solution to the problem. Students reflected on each of the questions and then participated in a group discussion. They were encouraged to generate situations in which the answer provided by one of Kleinman's questions would be integral to developing the best health care plan for a patient. Students were challenged to apply Kleinman's questions in patient encounters, when appropriate, throughout the APPE. Other methods of eliciting health beliefs that were introduced to students were the LEARN Model11 and the RESPECT Model.12

Students were posed questions about how they would approach a situation in which a patient had a health belief that was different from their own. A discussion often developed, with a variety of opinions and strategies raised by the students. The faculty member emphasized the importance of promoting an environment where patients feel comfortable sharing necessary culturally specific health care beliefs. This required that the students become aware of any personal stereotypes or biases they had and consciously minimize the role these beliefs played when engaging in a patient interaction. The faculty member also highlighted an approach to negotiating therapy choices. Students learned that when patients' health beliefs did not align with the culture of pharmacy, they should not dispel the patients' choice or belief, but rather work with the patient to determine a plan that satisfied both the patient and pharmacist.

Following the topic discussion, students practiced using Spanish interpreters at CAP. Patient counseling, collecting patient information, and conducting disease state management appointments all occurred on a regular basis with the assistance of an interpreter. The pharmacy employed 1 full-time bilingual technician and 1 part-time interpreter to facilitate conversations with Spanish-speaking patients. Students learned about the staff members' interpretation styles and also asked the interpreters questions to gain deeper insights into the Latino culture. These insights helped students expand their understanding of the dynamics between health and culture. There were also instances when the Language Line, a telephone interpreter service, was necessary. Students were introduced to this service as an alternative when an interpreter could not be physically present.

To understand the importance of customizing disease management programs to fit patients' lifestyles, students visited a local Mexican grocery store to become familiar with the foods offered. Students then developed an appropriate diabetic food plan for 1 day based on the products available in the store. The students spent approximately 1 hour with a Latina woman at the store comparing labels, asking questions about food preparation, and looking over the items on the shelves. When they returned to the pharmacy, they worked together to develop a complete food plan, including serving sizes. These food plans were then used as tools for the diabetes education program.

Because of the prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use within the Hispanic community, students were encouraged to ask patients if they used these products. Patients are often reluctant to disclose information about traditional medicine and therapy they use unless they are confident they will not be judged by the healthcare provider. Thus, pharmacy students were taught to remove the perceived stigma associated with CAM by beginning their series of questions with a statement that showed sensitivity towards CAM use. Students were also instructed to give examples of products or treatments that they had seen used in the culture so that patients had a clearer understanding about the question. Finally, the patients were told the reason the pharmacist needed to have a complete list of medications and therapies, so they would not worry about the consequences of their answers. Traditional healers (curanderos) are also used in the Mexican community, so students at CAP were taught to be aware of their purpose and prepared to encounter patients who use them.

Students also spent a 3-4 hour block of time in both an outreach clinic at a homeless shelter and an HIV/AIDS clinic. During each of these experiences, the student engaged in appropriate clinic activities with supervision from a healthcare provider. Students were given an overview of how the clinic operated, the typical patients seen, and the challenges as well as opportunities for patient care. Students were introduced to services that improved patient access to care and served as part of the healthcare team during patient appointments.

Achievement of APPE goals related to diversity were assessed, in part, through evaluation of daily log reflections and a student self-assessment survey of learning. The students used Likert-type scales to rate their level of agreement with 13 statements related to all aspects of the APPE. Assessment of diabetes knowledge, perceived value of rotation activities, impression of workload, opinion of preceptor accessibility, communication with diverse patient groups, and awareness of solutions to improve access to care were included in the evaluation tool, which has not been validated. Students were required to complete the self-assessment survey during the final week of the APPE.

ASSESSMENT

Forty-three students completed the CAP APPE from December 2004 through December 2007. Most of those who participated in the APPE were non-Hispanic white students from the Midwest. Although their life experiences varied, many of them had not practiced in a pharmacy with significant cultural diversity. There was some initial hesitancy by students to immerse themselves in their patients' culture, but once the first week of the rotation was over, they became more comfortable with the patient interactions. Responses to the site-specific evaluation were collected from 100% of the CAP APPE students (Table 1). Over 90% of students agreed that experiences at CAP taught them about counseling culturally diverse patients as well as methods to improve medication access to this population.

Table 1.

Student Self-Assessment of Learning Related to Diversity and Medication Access (N = 43)

Two major themes were identified in students' comments on the evaluation. Students were, for the most part, naive to professional interactions with diverse patient groups. Many made comments about not realizing the scope and magnitude of healthcare problems for uninsured and underinsured patients, especially those from culturally diverse backgrounds. Another theme from student evaluations was the positive responses generated from learning activities that centered on direct patient interactions. Students appreciated the chance to see how the healthcare team interacts with patients outside of traditional settings.

Students' daily logs captured many reflections about their journey towards cultural competence. Topic discussions were viewed as useful by students who recognized that talking about patient diversity could help them anticipate situations they might encounter in practice. Several students found conducting a patient counseling session with an interpreter to be a challenge and significantly more difficult than one-on-one counseling with an English-speaking patient. Student evaluation of the grocery store activity illustrated that it was an interesting and educational experience which raised awareness of another aspect of culture. Describing the multiple barriers to care that prevented patients from achieving optimal health outcomes was frequently documented in daily logs. The provider services and programs to improve medication access in health care settings were seen by students as invaluable.

DISCUSSION

Pharmacy students should not only learn about diverse patient groups in the classroom, but practical experiences should also be arranged that allow them to develop their skills. A survey of 50 pharmacy faculty members concerning potential barriers to implementing cultural competence material into curricular content found that 33% thought lack of APPE/clerkship sites that provide diverse patient populations was either a very important or an extremely important factor.13 Sites that serve culturally diverse groups should explore options for adding activities that advance students' cultural development. The activities at CAP may provide a framework for other APPE programs to consider. Although the primary focus of the CAP APPE was with Hispanic patients, students should be able to translate their learning to other ethnically diverse groups. Students also spent significant time interacting with indigent patients, whose health care options may have been different from what many students had experienced. These interactions taught students different options to improve access to health services, which could be translated to future pharmacy settings.

Other health professions have formed recommendations about teaching health disparities. According to suggestions from the Society of General Internal Medicine Health Disparities Task Force, health disparities should be reinforced repeatedly throughout the curriculum.14 Instead of a dedicated course, the task force believes it is more effective to use an integrated, combined approach. It helps to reinforce the “complexity and pervasiveness of disparities when a physician considers clinical care.” The Task Force goes on to offer that learning objectives centered on health disparities should focus on “examining and understanding attitudes,” “gaining knowledge of…health disparities,” and “acquiring skills to effectively communicate and negotiate.” The CAP APPE offers students all of these opportunities. The path towards becoming a culturally competent pharmacist is not short. It is a continuous process that requires both experiences and reflection for students to make progress. One cultural development model describes a 6-step process.15 It includes steps of cultural incompetence, cultural knowledge, cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, cultural competence, and cultural proficiency. Although completing one APPE will not make students culturally proficient, the goal is for the experience to move them forward in the process.

Students generally seemed to appreciate the cultural diversity they experienced during the community pharmacy APPE. Based on student comments, they were eager to interact professionally with diverse patients, which is something that many had not previously experienced. The clinic visits with HIV/AIDS and homeless patients allowed students to learn about programs most never knew existed. The grocery store visits allowed for learning to occur not only about nutrition, but it also provided an opportunity for students to grow in their cultural competence. For many students, this was their first step into a culturally diverse business, especially one where English was not the first language. This increased cultural awareness may allow students to be more appreciative of diverse populations.

Many student comments encouraged the development of additional clinic activities to allow students opportunities to interact with diverse patients, in addition to the HIV/AIDS clinic and homeless shelter. One of these potential student experiences is through a statewide migrant health project. The organization, which receives federal and state funding, operates temporary clinics that take primary health care to agricultural sites across Iowa. Resources are limited and schedules are often unpredictable, but pharmacy students could play an integral role in this setting.

One of the limitations to the survey were changes made to the CAP APPE between 2004 and 2007. There were variations in the activities offered not only due to availability of the activity and schedule of facilitators, but also modifications based on student feedback and preceptor discretion. This may have impacted the results because each student's experience was not exactly the same from year to year. Another limitation was that the self-assessments were not completely anonymous, which may have caused students to rate the experience higher, resulting in a potential bias towards favorable results. Evaluation of learning on this APPE occurred using a non-validated student self-assessment. While self-assessments can be useful, other professional methods to evaluate cultural competence such as the Patient Reported Physician Cultural Competency (PRPCC) Scale may be preferable.16 A more comprehensive evaluation of the students' degree of cultural competence is desirable and will be the focus of future work.

SUMMARY

Community Access Pharmacy APPE activities such as discussing issues surrounding diversity, interviewing patients with interpreters, visiting a Mexican grocery store, evaluating CAM , and experiencing outreach health care services helped prepare pharmacy students to interact with a diverse patient population and to raise awareness of solutions increasing access to care.

REFERENCES

- 1.What is Cultural Competency? Office of Minority Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.omhrc.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=11 Accessed October 1, 2008.

- 2.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin. US Census Bureau. Available at: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/ Accessed October 1, 2008.

- 4.Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.doc Accessed October 1, 2008.

- 5.Onyoni EM, Ives TJ. Assessing implementation of cultural competency content in the curricula of colleges of pharmacy in the United States and Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71 doi: 10.5688/aj710224. Article 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans E. An elective course in cultural competence for healthcare professionals. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70 doi: 10.5688/aj700355. Article 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assemi M, Cullander C, Suchanek Hudmon K. Implementation and evaluation of cultural competency training for pharmacy students. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:781–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quist RM, Law AV. Cultural competency: agenda for cultural competency using literature and evidence. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy. 2006;2:420–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez de Bittner M, Sias JJ. Washington DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2004. Working with Hispanic populations. APhA Partners in Self Care. Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berlin EA, Fowkes WC., Jr A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care – application in family practice. West J Med. 1983;139:934–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutha S, Allen C, Welch M. San Francisco, CA: Center for Health Professions, University of California at San Francisco; 2002. Toward Culturally Competent Care: A Toolbox for Teaching Communication Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assemi M, Mutha S, Suchanek Hudmon K. Evaluation of a train- the-trainer program for cultural competence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71 doi: 10.5688/aj7106110. Article 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:654–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells MI. Beyond cultural competence: a model for individual and institutional cultural development. J Community Health Nurs. 2000;17:189–99. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1704_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thom DH, Tirado MD, Woon TL, et al. Development and evaluation of a cultural competency training curriculum. BMC Medical Education. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]