Abstract

Objectives

To develop and implement an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) that would increase students' awareness of, acceptance of, and ability to apply public health concepts in pharmaceutical care.

Design

A 6-week APPE was developed that utilized a wide variety of activities including written assignments, role-play, direct patient care, reflective writing, and community outreach to explore various public health issues and their relation to the practice of pharmacy. To determine the students' perception of learning, a 5-question survey instrument was sent to students upon completion of the experience

Assessment

The results of the survey indicated high satisfaction with the APPE in a variety of different domains including provision of pharmaceutical care, providing patient education, exercising cultural competency, referring to community resources, and utilizing medication assistance programs.

Conclusion

The advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) provides students a unique opportunity to develop skills important to the practice of public health and expand understanding of the role of pharmacist in the public health setting.

Keywords: public health, experiential education, cultural competency, community engagement, advanced pharmacy practice experience

INTRODUCTION

The Institute of Medicine released a report in 2002 on disparities in healthcare provided to and received by racial and ethnic minorities and how healthcare providers themselves had contributed to the problem. In this report, the IOM discovered that it was “providers' own bias, prejudice, and stereotyping” that had created these disparities.1 The IOM recommended cross-cultural education of all current and future providers as an important tool in eliminating bias and prejudice and thereby closing the gap in quality of healthcare among minority and nonminority groups. Although physicians and nurses have traditionally been the leaders in and providers of public health services, pharmacists are becoming more involved. As a result, colleges and schools of pharmacy have begun incorporating public health principles into the curriculum. As the education of future pharmacists in the provision of public health expands, so too does the need for colleges and schools of pharmacy to provide opportunities for students to develop public health skills through experiential learning.

In April 2006, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy published “Caring for the Underserved: A delineation of educational outcomes organized within the Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework for Health Professions.”2 The framework identifies content areas with terminal educational outcomes for colleges and schools of pharmacy for the incorporation of public health issues into the curriculum. The document identifies several components of public health where pharmacists have a role and authority, including in evidence-based practice, clinical preventive services (health promotion), health systems and policy, community aspects of practice, and community services. Each of these components requires educating students in issues like cultural competency, health literacy, population-based health, health surveillance, and health policy. The Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) recommendations for Pharmacy Practice in 2015 include the provision of “patient-centered and population-based care” as well as the “promotion of wellness, health improvement, and disease prevention.”3 Both of these concepts can be identified as concepts related to public health, thereby strengthening the rationale for APPEs that focus in public health. These recommendations are also consistent with the definition of practicing culturally competent care. Cultural competency has many definitions, but may be defined most succinctly by Cross and colleagues as “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enables that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.”4

As a vital component of public health, cultural competency has gained attention as a necessary part of pharmaceutical education. There are several examples in the literature of didactic efforts and programs developed for doctor of pharmacy students to enhance cultural competency and health literacy awareness and skills.5,6 However, to date there has not been a description of these concepts being taught as skills in experiential learning. An APPE focused in public health serves to continue the students' acceptance and knowledge of public health concepts while giving them experiential opportunities to practice these skills.

The University of Missouri School of Pharmacy is located in the heart of the urban core of Kansas City. For over 10 years, the School of Pharmacy has had a partnership with the Kansas City Free Health Clinic (KCFHC), a nonprofit, “safety net” provider for over 12,000 uninsured and underinsured residents of the Kansas City metro area. As a “safety net” provider, KCFHC has a unique approach: all services are provided free of charge to the patient, including medications. In 2004 alone, almost 10,000 patients were served and over 24,000 prescription medications dispensed. Seventy-two percent of patients had a chronic disease (internal communication with KCFHC, September 2007). KCFHC is strongly committed to the Healthy People 2010 goals to reduce racial disparities in health care as 76% of the patients are minorities. The clinic serves as a training site for medical, social work, dental, mental health, occupational therapy, nursing, and pharmacy students from schools and colleges in the Kansas City area. These students are the primary providers of services and care to patients at KCFHC. In this setting, pharmacy students are given a unique opportunity to actively participate on an interdisciplinary care team while providing pharmaceutical care and medication therapy management to an underserved patient population.

Students in their final professional year are required to complete one 6-week General Medicine II APPE with pharmacy practice clinical faculty members. Currently there are 14 pharmacy practice clinical faculty members who teach General Medicine II, each of whom provides a unique experience based on their practice site while still accomplishing the overall goals of the APPE. The Kansas City Free Medical Clinic allows for the application of public health concepts such as cultural competency, framework of poverty, health belief models, medical interpretation, and health disparities in the provision of pharmaceutical care.

DESIGN

The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Curriculum Outcomes document focuses on educational outcomes in 3 categories: pharmaceutical care, systems management, and public health.7 From this framework, administrators and faculty members are encouraged to create discipline and content-specific outcomes that are meaningful within the context of their curriculum. Within the context of public health, outcomes in the provision of effective, quality health, and disease prevention services and the development of public health policy were recommended. The educational goals of the APPE were developed so as to incorporate these outcomes as well as to expand on them by including additional student outcomes in health literacy, health disparities, and cultural competency. These goals are best achieved when introduced and practiced throughout the curriculum and thus should be used in the development of APPE sites and activities.

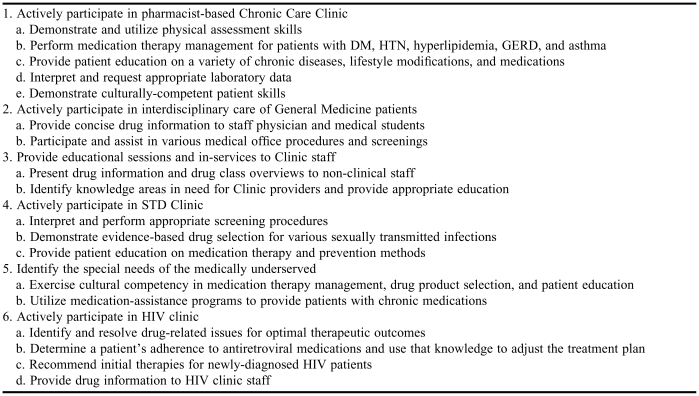

Goals and objectives for the APPE were developed utilizing the above recommendations as well as objectives required by the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Pharmacy. The objectives of the APPE are listed in Table 1. A variety of activities were used to accomplish these objectives and included direct patient care, written assignments, role play, and student presentations.

Table 1.

APPE Learning Objectives in Public Health

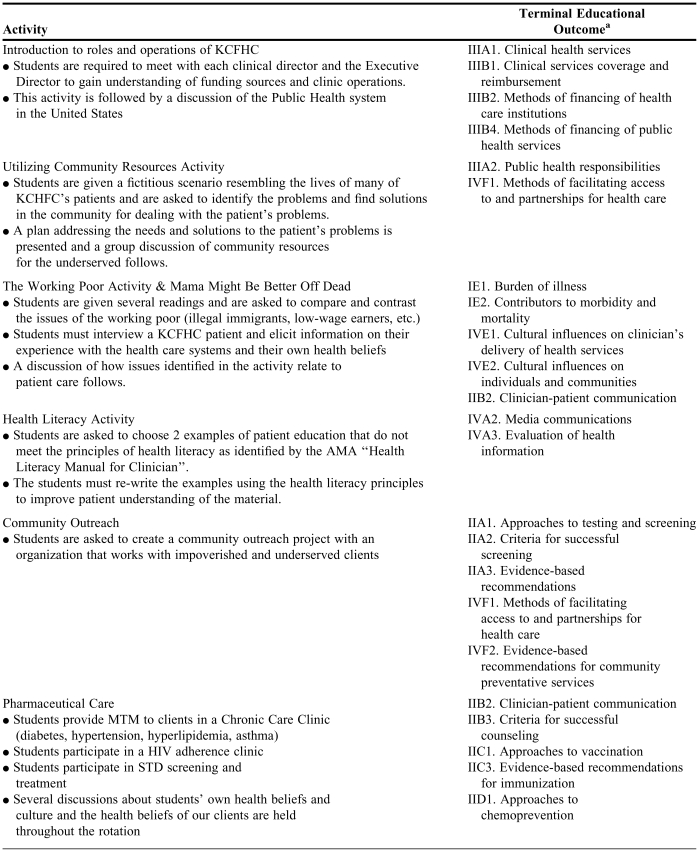

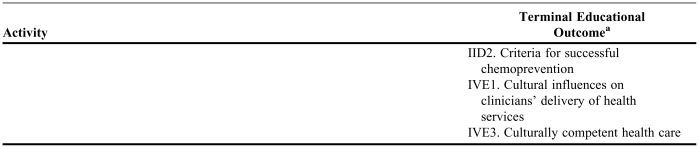

The students were required to participate in role-playing, written assignments, didactic teaching, and self-learning activities that covered various issues related to public health. They were then asked to incorporate concepts learned in these activities into the provision of pharmaceutical care at the Kansas City Free Medical Clinic. The activities were designed to give the students opportunities to practice these concepts and skills through facilitated simulation, and later in direct patient care. Table 2 lists the activities the students performed and their terminal educational outcomes.

Table 2.

Required Student Activities for an Advance Pharmacy Practice Experience in Public Health

American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Caring for the Underserved. A delineation of educational outcomes organized within the Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework for Health Professions. April 2006

Students were required to interview each clinical director and the Executive Director of the Kansas City Free Medical Clinic to help them better understand the organization of clinical and public health services. In doing so, the students were given an overview of clinic funding sources as well as clinic operations. This activity is followed by an informal discussion of the public health system in the United States in which students were introduced to a variety of public health concepts including health promotion, harm reduction, Healthy People 2010, and health-belief models.

As part of a community resource activity, students were given a fictitious scenario about a patient whose life situation resembled that of many of KCFHC's clients. The scenarios required that students identify issues related to the working poor, substance abuse, domestic violence, child abuse, malnutrition, children's health care, incarceration, government-funded social welfare programs, and access to healthcare. After identifying these issues in their scenario, they had to utilize real community resources to provide relief and/or assistance to their fictitious client. They were not allowed to utilize social workers in completion of this activity and they had to adhere to the limitations placed on their client (ie, if their client didn't have a telephone, they could not use the telephone to locate services). Additionally, the fictitious client had to actually qualify for the services utilized. The students were given approximately 1 week to complete this assignment which included providing a written plan for their client along with a personal reflection on difficulties, frustrations, and/or challenges encountered in acquiring services for their client. This activity was developed to facilitate student understanding of how to create partnerships for health care and other social services. A discussion of the activity followed completion of the written report. For the working poor activity, students were asked to read excerpts from the books, The Working Poor: Invisible in America, by David K. Shipler, and Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, by Barbara Ehrenreich. The readings discuss the problems common to the working poor, access to healthcare, and illegal immigrant issues. Students were asked to provide a written reflection of these readings including a discussion of common themes in the readings as well as a self-reflection on how these issues affect patient care. This activity served to continue to build the students' understanding of issues related to the provision of care in a resource-poor setting. Further discussion is had about the burden of illness, health disparities, and cultural influences on the delivery of health services.

For the health literacy activity, students were asked to read the American Medical Association's (AMA's) Health Literacy Manual for Clinicians in order to gain understanding of the basic concepts of health literacy, specifically written materials. The students were then asked to identify patient educational materials used at KCFHC that did not meet the principles of health literacy and thus could be confusing or misleading to patients. Once identified, the student had to recreate the material using concepts learned from the AMA manual. Additionally, the student had to provide a written analysis of what limitations the original material had and what changes were made for improvement of the new material

Along with their work at the KCFHC, the students were asked to create a community outreach day in an impoverished or underserved community within Kansas City and provide prevention education and outreach that matched the needs of the community. The students were responsible for identifying the community, speaking to community leaders in order to perform a needs assessment, designing an outreach activity, and implementing the activity. Students were encouraged to provide population-based health screenings. This allowed them to use knowledge gained during the “Utilizing Community Resources Activity” and apply it to direct patient care. Students reached out to a variety of community groups including a homeless shelter, a support group for commercial sex workers, and a walk-up fair for patients in an impoverished section of Kansas City. This activity not only encouraged the awareness of communities in need, but helped to create a sense of philanthropy in the students. Along with activities to encourage and enhance the students' understanding of the role of a pharmacist in public health, the students provided pharmaceutical care to clients with a variety of disease states at the KCFHC.

Students not only had to demonstrate their clinical knowledge in a pharmacist-managed chronic care clinic, but also practice the new skills developed in cultural competency, health literacy, and health belief models. The pharmaceutical care clinics served as a “laboratory” for the students to experiment with public health pharmacy practice issues. The students participated in several different clinics that provided pharmaceutical care to patients with disease states and prevention methods considered leading health indicators in Healthy People 2010, including obesity, smoking cessation, HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, and immunizations.8 The students also identified what diseases disproportionately affected minority patients were and incorporate that knowledge into their screening of patients at the office visit.

Students were given the opportunity to utilize a medical interpreter during the provision of pharmaceutical care. Proper communication techniques were taught and reinforced during visits that incorporated an interpreter. Students were encouraged to apply knowledge gained in the “working poor” activity on health needs specific to immigrants during these visits. Discussions on the role of culture and health belief models and subsequent discussion on the proper probing of patients for this information further enhanced the students' pharmacy practice skills.

The students were assessed a variety of different ways, both formally and informally. The students' written work was evaluated weekly. Students were evaluated not only on the grammatical and structural components of their writing, but also on their ability to reflect on their experiences.

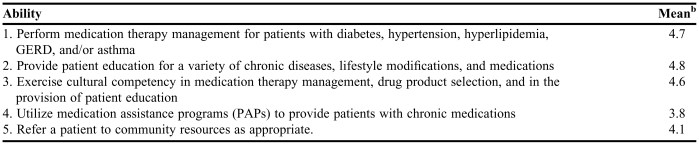

To determine the students' perception of learning, a 5-question survey instrument was sent to students who participated in the 2007-2008 APPE after they graduated. Five core objectives were determined and graduates were asked about their comfort level with their ability to perform stated objectives. Responses were based on a Likert scale on which 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree.

ASSESMENT

A wide variety of thought-provoking activities and a novel role for the pharmacist required the student to rethink the traditional role of the pharmacist on the healthcare team. Common themes emerged during the discussion of these activities, most commonly the concept of “competing priorities” in the provision of pharmaceutical care. The students are asked to make the connection between competing priorities and limited resources with the ability of the patient to adhere to the treatment plan. Another common theme to surface during discussion was the idea of health literacy and a patient or client's ability to navigate a health care system that is often above their literacy level. Lastly, this activity laid the groundwork for students as future practitioners to use knowledge of community resources to facilitate patient care. Students sometimes became frustrated at the beginning of the APPE as many of the activities did not have a “correct” or empirical answer, but rather, required the students to make connections with both social and behavioral ideas and the scientific practice of pharmacy. Students often struggled with the concepts, especially when the concepts of public health went against their own personally held beliefs (eg, harm reduction models, prevention of sexually transmitted diseases, condom usage, emergency contraception). Throughout the 6 weeks, students progressed from thinking in terms of absolutes and more towards developing the “art” of the practice of pharmacy. In their evaluations, many students expressed appreciation for the course and activities that pushed them to think about the practice of pharmacy as it relates to public health. Additionally, students reported that their understanding of the issues of the underserved were greatly enhanced by this experience.

Table 3 contains the results of the survey of graduates who had participated in the 2007-2008 APPE. Nine students responded. The results indicate high satisfaction and attainment of the objectives of the APPE. Students scored their ability to utilize medication assistance programs lowest.

Table 3.

Pharmacy Student's Postgraduation Assessment of an APPE in Public Health (N = 9)a

Abbreviations: APPE = advance pharmacy practice experience

One student only responded to question 1, therefore N = 8 for questions 2 through 5

1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree

DISCUSSION

An APPE in public health is a complement to cultural competency coursework in the curriculum. Cultural competence education is most effective when integrated into the curriculum and provided longitudinally. Students must be given the opportunity to “practice” what they learn and there is no better place to do that than in the experiential learning setting. An APPE in public health allows the preceptor to evaluate the students' knowledge, skills, and attitude in ways that case-based learning and simulation cannot. Future planning for the APPE includes the surveying of students prior to and after completion of the APPE to determine what affect the experience has on the students' perception of the role of pharmacists in public health and their own interest in pursuing a career in public health. A free health clinic provided an exceptional opportunity for students to gain knowledge in public health issues related to the practice of pharmacy. Further development of the site with complementary activities in core public health issues facilitated the students' understanding and acceptance of a pharmacist in a public health role.

Pharmaceutical care is defined as “the direct, responsible provision of medication-related care for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve a patient's quality of life.”9 From this definition, one can see the importance of pharmaceutical care as an essential, patient-centered component of caring for the underserved as it relates to the ultimate goal of increasing a patient's quality of life. One reason for the creation of IPPEs and APPEs that engage the community is that they plant seeds to continue engagement and expand the role of pharmacy.10 Students exposed to core issues related to the practice of pharmacy in the setting of public health can use that knowledge gained as future community leaders. The APPE then becomes more than a rewarding experience for the student; it becomes an opportunity to advance the profession. The impact of this will not only be seen in local communities, but in the global community as well. As Fincham stated, “We live in an ever shrinking world that is dangerous, yet so full of opportunities for us to exercise a public health mission that is global and in need of pharmacy expertise, impacts and outcome evaluations.”11

Barriers for implementation of an APPE in public health include clinical faculty funding, clinic acceptance, and faculty expertise. The clinical faculty position at the Kansas City Free Medical Clinic is 100% funded by the University of Missouri-Kansas City. The limited budgets of most free health clinics and federally qualified community health centers, combined with the limited scope of independent practice of pharmacists (as compared to nurse practitioners and physicians' assistants), leaves many clinics with the desire to have a pharmacist but an inability to find and justify funding for the position. However, as the ability of pharmacists to seek and receive reimbursement increases, the financial benefit of a pharmacist to a free health clinic or federally qualified community health clinic will be recognized. This will also enhance clinic administrators' understanding of the value of pharmaceutical care in the medical treatment of the underserved. Lastly, pharmacy faculty members may be reluctant to discuss issues like cultural competency, health disparities, medical interpretation, and caring for the underserved with students due to a deficit of their own training in these areas. Discussion of these issues in pharmacy school curriculum is a fairly recent trend. However, there are many excellent educational resources for pharmacists and pharmacy faculty members. Appendix 1 contains a brief list of resources for providers looking to gain or enhance their skills.

The APPE is the “icing on the cake” of a fully integrated cultural competency education framework that is sustainable and rewarding to students. As the profession continues to encourage expanded roles and responsibilities for pharmacists, APPEs focused in public health will become the foundation for this progress.

SUMMARY

An advanced pharmacy practice experience in public health that utilizes multiple modalities for learning is an effective way of incorporating cultural competency and health disparities into of the provision of pharmaceutical care. The APPE has been demonstrated to be sustainable, rewarding, and well accepted by doctor of pharmacy students and is replicable in diverse settings that care for underserved populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A special thanks to Sheridan Wood, Sally Neville, RN, MSN, and Craig Dietz, DO, at the Kansas City Free Medical Clinic for their continued support.

Appendix 1. Educational Resources for Cultural Competency Training

Addressing Health Care Disparities: Cultural Competence in Faculty Development Program. Center for the Health Professions. University of California, San Francisco. Information available at: http://www.futurehealth.ucsf.edu/TheNetwork/

Mutha S et al. (2002) Toward Culturally Competent Care—A Toolbox for Teaching Communication Strategies. San Francisco, California: Center for the Health Professions at the University of California, San Francisco. Available at: http://futurehealth.ucsf.edu/TheNetwork/Default.aspx?tabid=290

The Commonwealth Fund. Contains many online and written training guides for reducing health disparities and increasing cultural competence. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/

The California Endowment. Contains online and written training guides for enhancing cultural competency. Available at: http://www.calendow.org/Collection_Publications.aspx?coll_id=26&ItemID=316

Think Cultural Health. A program from the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health contains CME and CE programs. Available at: http://www.thinkculturalhealth.org/

National Center for Cultural Competency. Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Contains training for cultural and linguistic competency. Available at: http://www11.georgetown.edu/research/gucchd/nccc/foundations/frameworks.html

REFERENCES

- 1.Unequal Treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington D.C.: The National Academies Press: 2003. Board on Health Sciences Policy. Institute of Medicine. Available online at: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=030908265X [PubMed]

- 2.Caring for the Underserved. A delineation of education outcomes organized within the Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework for Health Professions. April 2006. American Association of Colleges of PharmacyAvailable online at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/CurricularResourceCenter/7701_CaringfortheUnderservedCurriculumFramework(2).pdf

- 3.Pharmacy Practice in 2015. Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. November 10, 2004.

- 4.Cross T, Bazron B, Dennis K, Isaacs M. Towards A Culturally Competent System of Care, Volume 1. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assemi M. Cullander Norman KS. implementation and evaluation of a cultural competency training for pharmacy students. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;38:781–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sicat BL, Hill LH. Enhancing student knowledge about low health literacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(4) Article 62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education Advisory Panel, Educational Outcomes 2004. American Academy of Colleges of PharmacyAvailable online at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/Resources/6075_CAPE2004.pdf.

- 8.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health Second Edition Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, November 2000 Available online at http://www.healthypeople.gov/

- 9.American Society of Health Systems Pharmacists. ASHP Statement on pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50:1720–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemire RE. Community Engagement. Presented at the 107th American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Annual Meeting. San Diego, California. July 2006

- 11.Fincham JE. Global public health and the academy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(1) doi: 10.5688/aj700114. Article 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]