Abstract

The Evans County Heart Study (ECHS), initiated in 1960, was one of the first major studies to document cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks for African Americans and Caucasians with elevated blood pressures. In the early 1970’s, the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program (HDFP), with a site in Georgia (HDFP-GA) was one of the first major studies to demonstrate that treating hypertension with stepped care (SC), versus referred care (RC), has better short-term outcomes. With this background, study objectives were to evaluate 30-year survival and cardiovascular outcomes of the HDFP-GA and to compare outcomes of these patients with 1619 hypertensive individuals (30-69 years of age) from the ECHS. HDFP-GA patients included 688 individuals (black [n=267]; white [n=421]) randomized to RC (n=341) and SC (n=347). The ECHS was comprised of 733 black and 886 white hypertensives. All-cause mortality and CVD mortality were assessed in the HDFP-GA and compared to the ECHS hypertensives. After 30-years of follow-up, 65.7% of the HDFP-GA cohort had died compared with a similar 65.8% of the ECHS hypertensives. However, CVD mortality rates, while similar for the SC and RC arms, were lower than in the HDFP-GA total study group than the hypertensive participants of ECHS (32.6% vs. 40.3% p<.001). CVD survival rates for both SC and RC HDFP-GA arms were significantly better than population-based hypertensive individuals in the ECHS, with consistent benefits in all four race-sex groups. These results identify the importance of long-term follow-up of individuals in hypertension studies and trials that include CVD outcomes.

Introduction

Population disease risk from high blood pressure was identified in the 1950s and 1960s in several prospective studies including Evans County1, Charleston Heart2, Framingham3, Tecumseh 4, Chicago5, and Minneapolis6. Thus, hypertension is a longstanding and well recognized risk factor for cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, peripheral vascular and renal disease1-6. The benefits of high blood pressure treatment and reduction identified from results from the Veterans Administration (VA) in the 1960’s.7 These results led to the recommendations for measurement in the clinical setting.8 The benefits of blood pressure reduction were further confirmed with a randomized control trial with the VA.9 These findings prompted further study to determine if hypertension treatment benefits could be achieved in the general population, and if the systematic medical care of high blood pressure was more effective than usual medical care in the community.10 The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program (HDFP) was implemented in 1972 to assess these benefits. The HDFP included 14 clinical centers in the United States and included hypertensive individuals age 30-69 years randomized to Stepped Care (SC) and Referred Care or regular/usual care (RC) for 5-year duration.11 The disease burden from elevated blood pressure is particularly high for African Americans and residents of the southeastern United States.1,2 These racial and geographic disparities in hypertension risks are independent of socio-economic status.1,2,5 Thus epidemiological studies should consider high risk geographic and race groups in population-based assessments. One of the 14 HDFP clinical sites was located in rural Georgia around Evans County (HDFP-GA), a Southeastern population with a large proportion of African American men and women.

Sustained blood pressure reduction was observed in both arms of the HDFP study, but better blood pressure control was achieved with SC.11 The reduction in total and cardiovascular mortality in the SC as compared to RC arms of HDFP were, in fact, attributed to better control in the SC group. Similar findings in reduced mortality was identified at 6.7 years of follow-up.12 Nevertheless, differential outcomes between the SC and RC arms of HDFP may have been limited by the relatively short length of follow-up and comparatively few cardiovascular events and deaths.11 The current study assessed long-term outcomes in the HDFP-GA cohort and compared the long-term outcomes of the hypertensive participants of the Evans County Heart Study (ECHS).

Methods

The analyses for this study compare all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in HDFP-GA with the individuals with elevated blood pressures in the ECHS population-based cohort. The blood pressure values were obtained from the ECHS baseline assessments in 1960. Thirty year CVD and all-cause mortality rates, as well as survival curves were, compared for the participants of the two study groups. Though the two cohorts resided in the same geographic area, the two study groups were independent of one another.

HDFP-GA

The HDFP-GA represents the HDFP site located in the Evans County region of Georgia. All 14 clinical sites, including HDFP-GA, followed the same protocol for sampling, screening, and physical assessments.13 All participants had diastolic blood pressures greater than 90 mm hg and were considered hypertensive. After population-based sampling and screening, 688 hypertensive individuals were randomized to the RC (n=341) and SC (n=347) arms for the trial13. The HDFP-GA study group included 158 Caucasian females, 263 Caucasian males, 148 African American females and 119 African American males. Vital status of the HDFP-GA cohort was determined through multiple means including Social Security Administration’s Death Index, Ancestry.com, review of newspaper obituaries and the National Death Index.14 Death certificate information was obtained on all deceased participants with causes of death and co-morbidities at time of death identified from the death records. A panel of six individuals participated in reconciling and adjudicating the vital status of the 688 subjects with cause of deaths and associated co-morbid conditions contributing to death obtained from the death certificates.

Evans County Heart Study

During the 1960-1962 period, all non-institutionalized residents of Evans County, Georgia, 40 years or older and 50% of those 15-39 years were invited to participate in an epidemiologic, closed community-based cohort study15. With 90% and higher consent rates across races and genders, 3,102 people completed the baseline assessment. In order to compare with the HDFP-GA cohort, only individuals identified with high blood pressure (140/90 mm hg) and ages 30-69 years were included resulting in 1619 individuals (453 (28%) Caucasians females, 433 (27%) Caucasian males, 406 (25%) African American females, and 327 (20%) African American males). Of the 1619, there were 218 hypertensives with isolated systolic hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm hg and diastolic blood pressure <90 mm hg). The initial blood pressure measurement recorded during the 1960 assessment used mercury sphygmomanometers with standard cuffs with subjects seated and assessment using the left arm. These blood pressure values from this assessment were not medically treated and were considered ‘natural’. Hypertension was defined as blood pressured greater than or equal to 140/90 mm hg. Vital status was assessed for 30 year follow-up using similar mechanisms as described for HDFP-GA. Cause of death was determined from death certificate. As hypertension in the HDFP-GA was based only with diastolic blood pressures, the analyses were repeated in the ECHS without the isolated systolic hypertensives.

Data Analysis

Seven-year and thirty-year mortality rates were determined by race-sex groups for the ECHS and HDFP-GA cohorts for all-cause and CVD. Rates between the studies were compared using chi-square tests. Survival curve estimates were calculated for 30-year all cause and CVD mortality using the Kaplan-Meier method. Heterogeneity in survival trends between ECHS and HDFP-GA was determined using the Log-Rank Test. All statistical tests were performed using two-sided alpha level of 0.05 using SAS software version 9.1 (Cary, NC). As a standard practice in the analysis of observational studies, adjustment for multiple comparisons was not included.

Results

In 1960, the majority (68.5% (1619 of the 3102 total cohort)) of ECHS adults 30-69 years were considered hypertensive with blood pressure values 140/90 mm hg and greater at the baseline examination. African American men and women had higher rates of high blood pressure than their Caucasian counterparts (81.3% vs. 60.1% and 83.4% vs. 60.2% respectively). For the ECHS hypertensive study cohort, 45% were African American and 55% were Caucasian.

In 1972, 39% of the 688 participants of HDFP-GA cohort were African American (148 women; 199 men) and 61% were Caucasian (158 women; 263 Caucasian men). The distribution of race-sex groups was similar in both the RC and the SC arms of the HDFP-GA study.

While all individuals in both the ECHS and HDFP-GA study groups were considered hypertensive, the blood pressure distributions were significantly higher (p<0.01) for the ECHS cohort. Mean systolic blood pressure for ECHS was 165 mm hg compared with 156 mm hg for HDFP-GA. Likewise, mean diastolic blood pressure were 101 mm hg and 99 mm hg, respectively. In addition, the EHS cohort included 218 individuals with isolated systolic hypertension.

All-Cause Mortality

Seven-year mortality was determined for both the ECHS and HDFP-GA cohorts (Table 1). Mortality rates after 7 years of follow-up were similar for both the RC and SC arms of the HDFP-GA with 12.1% of the study group deceased. Mortality rates were slightly higher among men in the HDFP-GA. Similarly 12.3% of the ECHS hypertensive cohort had died after 7 years of follow-up with similar race-sex patterns seen in the HDFP-GA.

Table 1.

7-year All Cause Mortality (percent of participants) for Hypertension-Detection and Follow-up Program-Georgia site (HDFP-GA) and Evans County Heart Study hypertensive cohort (ECHS)by race-sex group

| Cohort Group | Caucasian Females | Caucasian Males | African American Females | African American Males | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred Care | 12.2% | 13.3% | 12.5% | 18.6% | 13.8% |

| Stepped Care | 10.5% | 13.3% | 5.3% | 10.0% | 10.4% |

| P-value | 0.742 | 0.990 | 0.120 | 0.178 | 0.170 |

| Total HDFP-GA | 11.4% | 13.3% | 8.8% | 14.3% | 12.1% |

| ECHS | 8.0% | 17.1% | 8.6% | 16.5% | 12.3% |

| P-value | 0.189 | 0.185 | 0.952 | 0.570 | 0.879 |

Nearly two-thirds (65.7%) of the HDFP-GA cohort had died within the 30-year follow-up period. Similar to the 7-year all-cause mortality, no significant differences were observed between the RC and SC arms of the HDFP-GA after 30 years of follow-up (Table 2). The mortality rates were again higher for men than women. The all-cause 30-year mortality among the ECHS hypertensives was similar with 65.8% of the study group deceased. No differences were detected in mortality rates between the HDFP-GA and ECHS for any of the four race-sex groups after 30 years of follow-up.

Table 2.

30-year All Cause Mortality (percent of participants) for Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program-Georgia site (HDFP-GA) and Evans County Heart Study hypertensive cohort (ECHS) by race-sex group

| Cohort Group | Caucasian Females | Caucasian Males | African American Females | African American Males | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred Care | 63.4% | 68.0% | 63.9% | 72.9% | 66.9% |

| Stepped Care | 60.5% | 72.6% | 50.0% | 70.0% | 64.6% |

| P value | 0.709 | 0.412 | 0.088 | 0.728 | 0.524 |

| Total HDFP-GA | 62.0% | 70.3% | 56.8% | 71.4% | 65.7% |

| ECHS | 59.4% | 75.3% | 56.9% | 73.1% | 65.8% |

| P-value | 0.559 | 0.1521 | 0.977 | 0.728 | 0.969 |

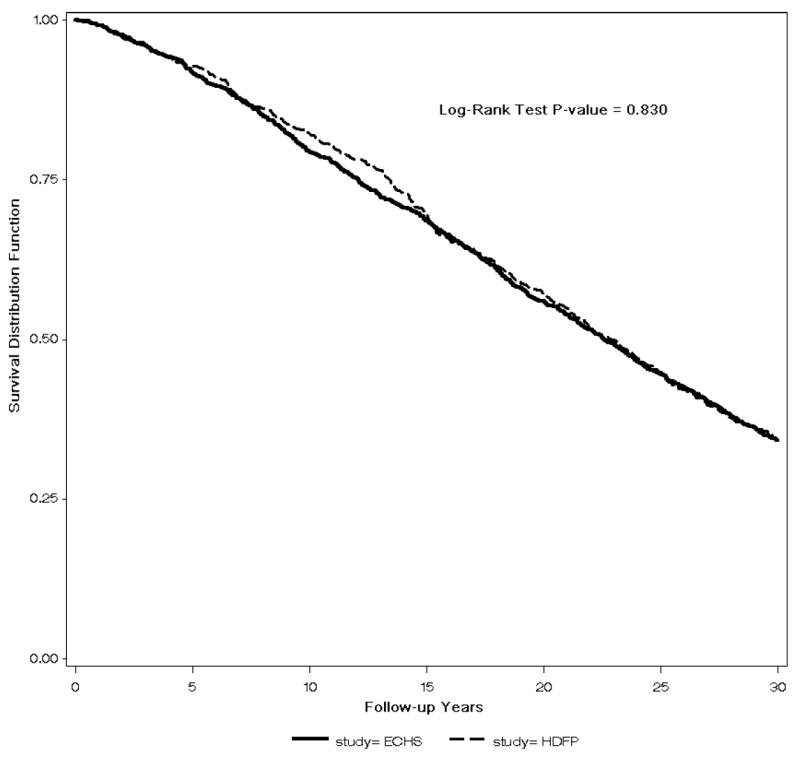

Figure 1 presents the 30-years survival curves for the HDFP-GA and ECHS cohorts. Survival trends were statistically similar for the 30-year follow-up period.

Figure 1.

Survival curves for all-cause mortality for Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program-Georgia Site (HDFP) and Evans County Heart Study hypertensive cohort (ECHS)

CVD Mortality

Table 3 presents the 7-year CVD mortality rates for the two cohorts. As reported for 7-year all-cause mortality, no significant differences for CVD mortality rates were detected for the two arms in HDFP-GA. The ECHS hypertensives and HDFP-GA cohorts were similar with the exception of African American females where the HDFP-GA showed significantly lower CVD mortality. However, after 7 years less than 10% of either cohort had died from CVD.

Table 3.

7--year Cardiovascular Disease Mortality (percent of participants) for Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program-Georgia site (HDFP-GA) and Evans County Heart Study hypertensive cohort ECHS) by race-sex group

| Cohort Group | Caucasian Females | Caucasian Males | African American Females | African American Males | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred Care | 6.1% | 6.3% | 2.8% | 11.9% | 6.5% |

| Stepped Care | 5.3% | 6.7% | 1.3% | 3.3% | 4.6% |

| P value | 0.821 | 0.891 | 0.528 | 0.078 | 0.291 |

| Total HDFP-GA | 5.7% | 6.5% | 2.0% | 7.6% | 5.5% |

| ECHS | 4.4% | 10.2% | 7.1% | 8.0% | 7.4% |

| P-value | 0.514 | 0.094 | 0.022 | 0.892 | 0.111 |

Nearly one-third of the HDFP-GA cohort had died from CVD after 30-years of follow-up (Table 4). The 30-year CVD mortality rates were similar for the two arms of the study with the exception of African American men, where rates for SC were significantly lower than RC. When compared with ECHS hypertensives, the HDFP-GA cohort had significantly lower 30-year CVD mortality rates. These lower rates for the HDFP-GA cohort were most evident for Caucasian men and African American women.

Table 4.

30-year Cardiovascular Disease Mortality (percent of participants) for Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program-Georgia site (HDFP-GA) and Evans County Heart Study hypertensive cohort (ECHS) by race-sex group

| Cohort Group | Caucasian Females | Caucasian Males | African American Females | African American Males | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referred Care | 29.3% | 34.4% | 26.4% | 44.1% | 33.1% |

| Stepped Care | 35.5% | 34.8% | 27.6% | 26.7% | 32.0% |

| P value | 0.401 | 0.940 | 0.865 | 0.047 | 0.748 |

| Total HDFP-GA | 32.3% | 34.6% | 27.0% | 35.3% | 32.6% |

| ECHS | 39.2% | 46.0% | 37.2% | 39.5% | 40.3% |

| P-value | 0.184 | 0.003 | 0.026 | 0.425 | 0.001 |

Figure 2 presents the 30-year CVD survival for the HDFP-GA and ECHS hypertensive cohorts. In contrast to the all-cause mortality where the survival curves were similar for the two study groups, the HDFP-GA had significantly better survival for CVD. The difference in survival is evident after 7 years of follow-up and remains consistent through the 30 years of follow-up (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for cardiovascular disease for Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program-Georgia Site (HDFP) and Evans County Heart Study hypertensive cohort (ECHS)

Discussion

The first noteworthy result is the significant difference in 30-year CVD mortality between HDFP-GA subjects and ECHS hypertensive subjects residing in this high risk region of the United States. This difference in CVD outcomes may be due in part to a direct or indirect consequence of the five-year period of antihypertensive therapy in HDFP-GA. Both study groups included a diverse population of hypertensive individuals residing in a similar rural area of Georgia. The observed difference was evident in CVD mortality with overall mortality similar for ECHS and HDFP-GA subjects. The mortality difference was observed at five to seven years after baseline, and persisted for the duration of the 30-year period of observation.

The results have re-emphasized the early studies of the ECHS identifying elevated blood pressure as exceptionally prevalent in the Evans County cohort, particularly among African Americans.16 A unique attribute of the ECHS was hypertension based on elevated blood pressures that would be considered ‘natural’, i.e. without treatment at the 1960 baseline examination. Interpretation of population-based studies of high blood pressure are complicated by differences in treatment practices that were prevalent in the 1970’s, as well as issues such as compliance with therapy, etc.17

Both all-cause and CVD mortality at 5-years and 6.7 years of follow-up were higher at the HDFP-GA site than the overall HDFP rates from all 14 sites.11,12 The geographic disease burden for residents of the Southeast is evident with this comparison. The CVD mortality rates reported at 5-years and 6.7 years from both SC and RC from the entire (all 14 sites) HDFP cohort were lower than either arm in the HDFP-GA study group.

The HDFP has demonstrated the success of systematic stepped care hypertension treatment protocols at the community health care setting with improvements in outcomes during the 5 year study period18-22. As hypertension represents a lifelong condition, 5 years represent a relatively limited follow-up period for hypertensive individuals. Likewise, the assessment of racial and geographic differences in hypertension-related outcomes is more robust with multiple years of follow-up. However, long-term follow-up of the entire HDFP cohort is complicated as the records and participant information are maintained separately at each of the 14 clinical sites.23 As described in the current study, the vital status and cause of death ascertainment required the use of multiple systems and data resources. Thus, long-term outcome assessment is most efficiently and practically completed at the individual clinical site, as done with the HDFP-GA site. Longer term follow-up is required to observe a greater number of adverse outcomes, even among individuals with hypertension. The results of these analyses from the HDFP-GA suggest similar outcomes for both Caucasian and African American hypertensives in a structured study.

Nonetheless, while blood pressure control is achieved primarily in the clinical setting, there are multiple factors outside the medical setting that should be considered.24 The comparison of the hypertensive participants from the ECHS with the HDFP-GA cohort resource provides an opportunity to assess blood pressure and outcomes in Caucasians and African Americans in a similar geographic setting. The results suggest that hypertension treatment strategies implemented in the early 1970’s as well as participation in a structured trial such as HDFP, may be associated with improved 30-year CVD outcomes.

While this assessment produces useful results, there are several limitations that should be considered. First, the baseline values from ECHS were attained in 1960 while the HDFP-EC values were from 1972. Medical practices and patient behaviors changed during this time period. In addition, while the blood pressures from ECHS were considered ‘natural’ and untreated in 1960, treatment regiments could have begun soon after the assessment. In particular, hypertension treatment has drastically changed with practice guidelines over the past 3 decades. Since 1977, the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC) has published guidelines on the diagnosis and management of hypertension.25-31 These reports have included the definitions of elevated blood pressure which have changed over the years. Likewise, treatment recommendations have evolved over the course of the JNC reports. In the early reports, only diuretics or β-blockers (BBs) were recommended for first-line therapy. As new classes of treatment were developed and studied, recommendations were adjusted accordingly. The most recent report, JNC 7, also advocates consideration of angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is), and/ or calcium-channel blockers (CCBs) for first-line use in uncomplicated hypertension.31 Likewise, the early JNC reports have generally advocated monotherapy as initial drug therapy for hypertension. However, the most recent report acknowledges that there may be a role for first-line combination therapy in treating patients with Stage 2 hypertension, defined as systolic BP ≥ 160 mm hg and diastolic BP ≥ 100 mm hg.31 An additional limitation includes the assessment of hypertension for the two study groups. For ECHS, hypertension was determined from the blood pressure measured at the 1960 baseline assessment while the HDFP-GA participants were screened prior to enrollment in the study. Thus, hypertension was based on multiple blood pressure measurements for HDFP-GA compared with a single measurement for ECHS.

These results indicate the importance of long-term follow-up for all individuals with elevated blood pressures. Studies and clinical trials, particularly those including CVD, should incorporate longer follow-up to accurately assess outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from Novartis and the Black Pooling Project NHLBI 1R01HL072377.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tyroler HA, Heyden S, Bartel A, Cassel J, Cornoni JC, Hames CG, et al. Blood pressure and Cholesterol as Coronary Heart Disease risk Factors. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1971;128:907–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lackland DT, Keil JE, Gazes PC, Hames CG, Tyroler HA. Outcomes of black and white hypertensive individuals after 30 years of follow-up. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 1995;17:1091–1105. doi: 10.3109/10641969509033654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein FH, Ostrander LD, jr, Johnson BC, Payne MW, Hayner NS, Keller JB, et al. Epidemiological studies of cardiovascular disease in a total community – Tecumseh, Michigan. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1965;62:1170–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-62-6-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamler J, Stamler R, Rhomberg P, Dyer A, Berkson DM, Reedus W, et al. Multivariate analysis of the relationship of six variables to blood pressure: findings from Chicago community surveys, 1965-1971. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1975;28:499–525. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(75)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keys A, Taylor HL, Blackburn H, Brozek J, Anderson JT, Simonson E. Coronary heart disease among Minnesota business and professional men followed fifteen years. Circulation. 1963;28:381–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.28.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. Veteran Administration. Cooperative Study group on Antihypertensive Agents. JAMA. 1967;202:1028–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkendall WM, Burton AC, Epstein FH, Freis ED. Recommendations for human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometers. Circulation. 1967;36:980–988. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.36.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steering Committee. The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program. The Epidemiology and Control of Hypertension. 1975;1:663–672. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Mortality by race-sex and age. Reduction of mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562–2571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daugherty SA. Mortality findings beyond five years in the Hypertension Detection and follow-up Program (HDFP) Journal of Hypertension. 1988;6(supp4):S597–S601. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198812040-00187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis BR, Ford CE, Remington RD, Stamler R, Hawkins CM. The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program design, methods, and baseline characteristics and blood pressure response of the study population. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 1986;29(Supl 1):11–28. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(86)90032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curb JD, Ford CE, Pressel S, Palmer M, Babcock C, Tyroler HA. Ascertainment of vital status through the National Death Index and The Social Security Administration. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1985;121:754–766. doi: 10.1093/aje/121.5.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hames CG. Evans County Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Epidemiologic Study. Introduction. Arch Int Med. 1971;128:883–886. doi: 10.1001/archinte.128.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson JL, Heineman EF, Heiss G, Hames CG, Tyroler HA. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and mortality among black women and white women aged 40-64 years in Evans County, Georgia. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;123:209–220. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong KL, Cheung BMY, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KSL. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999-2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HDFP Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the HDFP. I. reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562–2571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HDFP Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the HDFP. II mortality by race-sex and age. JAMA. 1979;242:2572–2577. doi: 10.1001/jama.1979.03300230028022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith EO, Hardy J, Cutter GR, Curb JD, Hawkins CM. Application of survival analysis techniques to evaluation of factors affecting compliance in clinical trials of hypertension control. Controlled Clinical Trails. 1980;1:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- 21.HDFP Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the HDFP. III Reduction in stroke incidence among persons with high blood pressure. JAMA. 1982;247:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy RJ, Hawkins CM. The impact of selected indices of antihypertension therapy on all cause mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:566–574. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HDFP Cooperative Group. Blood pressure studies in 14 communities: a two-stage screen for hypertension. JAMA. 1977;237:2386–2301. doi: 10.1001/jama.1977.03270490025018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banegas JR, Segura J, Sobrino J, Rofrigues-Artalejo F et al. Effectiveness of blood pressure control outside the medical setting. Hypertension. 2007;49:62–68. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000250557.63490.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. A cooperative study. JAMA. 1977;237:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The 1980 Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:1280–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The 1984 Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1047–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The 1988 Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1023–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Fifth Report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC V) Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:154–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]