Abstract

Neuropeptide S (NPS) was identified as the endogenous ligand of an orphan receptor now referred to as the NPS receptor (NPSR). In the frame of a structure-activity study performed on NPS Gly5, the NPSR ligand [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS was identified. [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS up to 100 μM did not stimulate calcium mobilization in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells stably expressing the mouse NPSR; however, in a concentration-dependent manner, the peptide inhibited the stimulatory effects elicited by 10 and 100 nM NPS (pKB, 6.62). In Schild analysis experiments [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (0.1–100 μM) produced a concentration-dependent and parallel rightward shift of the concentration-response curve to NPS, showing a pA2 value of 6.44. Ten micromolar [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS did not affect signaling at seven NPSR unrelated G-protein-coupled receptors. In the mouse righting reflex (RR) recovery test, NPS given at 0.1 nmol i.c.v. reduced the percentage of animals losing the RR in response to 15 mg/kg diazepam and their sleeping time. [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (1–10 nmol) was inactive per se but dose-dependently antagonized the arousal-promoting action of NPS. Finally, NPSR-deficient mice were similarly sensitive to the hypnotic effects of diazepam as their wild-type littermates. However, the arousal-promoting action of 1 nmol NPS could be detected in wild-type but not in mutant mice. In conclusion, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS behaves both in vitro and in vivo as a pure and selective NPSR antagonist but with moderate potency. Moreover, using this tool together with receptor knockout mice studies, we demonstrated that the arousal-promoting action of NPS is because of the selective activation of the NPSR protein.

Neuropeptide S (NPS) is a newly discovered peptide that binds and activates a previously orphan G-protein-coupled receptor, now referred to as NPSR (Xu et al., 2004). NPS and NPSR are expressed at high levels in the brain and in a few peripheral tissues (Xu et al., 2004). The distribution of NPSR and the neurochemical characteristics of neurons expressing NPS in the rat brain were recently reported by the same group (Xu et al., 2007). In cells expressing recombinant NPSR, NPS was demonstrated to stimulate calcium mobilization and cAMP levels (Xu et al., 2004; Reinscheid et al., 2005). Little is known regarding the effects of NPS in tissues expressing the native NPSR. However, it has been reported recently that NPS modulates neurotransmitter release from mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes by inhibiting noradrenaline, serotonin, and glycine outflow (Raiteri et al., 2008). As far as in vivo actions of NPS are concerned, the following animal studies demonstrated that the NPS/NPSR system modulates several biological functions, including locomotor activity (Xu et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2006; Rizzi et al., 2008), wakefulness (Xu et al., 2004; Rizzi et al., 2008), anxiety (Xu et al., 2004; Leonard et al., 2008; Rizzi et al., 2008; Vitale et al., 2008), and food intake (Beck et al., 2005; Ciccocioppo et al., 2006; Niimi, 2006; Smith et al., 2006).

To deeply investigate the physiological and pathological roles played by the NPS/NPSR system and to evaluate possible therapeutic indications of novel drugs interacting with NPSR, the identification of selective NPSR ligands, particularly antagonists, is mandatory. Until now, the only NPSR antagonists described in literature are two closely related bicyclic piperazines, SHA 66 and SHA 68 (Okamura et al., 2008). These compounds behaved as selective, competitive, and fairly potent (pA2 ≈ 7.5) NPSR antagonists in calcium mobilization studies performed on cells expressing the recombinant receptor (Okamura et al., 2008). In vivo in mice, 50 mg/kg SHA 68 was able to partially counteract the stimulatory effects of NPS on locomotion. However, this molecule has only limited blood brain barrier penetration, and this may explain why only half of the motor-activating effect of NPS was blocked at relatively high doses of antagonist (Okamura et al., 2008). Despite this, SHA 68 certainly represents a useful tool for NSP-NPSR system investigations as demonstrated by recent studies in which NPS evokes anxiolytic effects and facilitates extinction of conditioned fear responses when administered into the amygdala in mice, whereas SHA 68 exerts functionally opposing responses, indicating that the endogenous system is involved in anxiety behavior and extinction (Jüngling et al., 2008).

To identify novel interesting ligands for the NPSR receptor, we and others performed structure-activity studies on the NPS peptide sequence, which demonstrated that the N-terminal part of the peptide, in particular the sequence Phe2-Arg3-Asn4, is crucial for biological activity (Bernier et al., 2006; Roth et al., 2006). Subsequent studies were focused on conformation-activity relationships (Tancredi et al., 2007) and on Phe2 of the NPS sequence (Camarda et al., 2008). In the frame of these studies, some NPSR peptide ligands were identified, including [Ala3]NPS (Roth et al., 2006), [Aib5]NPS (Tancredi et al., 2007), and [4,4′-biphenyl-Ala2]NPS (Camarda et al., 2008), which behaved as partial agonists in vitro in the calcium mobilization assay. [Ala3]NPS was also evaluated in vivo where it partially blocked the stimulatory effect of NPS on mice locomotor behavior (Calo et al., 2006) and the inhibitory action of NPS on palatable food intake in rats (Ciccocioppo et al., 2006).

In a structure-activity study on position 5 of NPS, we identified [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS as a peptidergic NPSR receptor ligand. In the present study, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS has been characterized pharmacologically in vitro using HEK293 cells stably expressing the mouse NPSR (HEK293mNPSR) and the fluorometric imaging plate reader FlexStation II and in vivo investigating its effects in the mouse righting reflex (RR) recovery test. Moreover, in the RR test, under the same experimental conditions, the phenotype and sensitivity to NPS were assessed in wild-type [NPSR(+/+)] mice and in NPSR-deficient mice [NPSR(-/-)].

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture. HEK293mNPSR cells were generated as described previously (Reinscheid et al., 2005) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and hygromycin B (100 mg/l) and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified air. HEK293mNPSR cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells/well into poly-d-lysine-coated 96-well black, clear-bottom plates.

Calcium Mobilization Experiments. The following day, the cells were incubated with medium supplemented with 2.5 mM probenecid, 3 μM of the calcium-sensitive fluorescent dye Fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester, and 0.01% Pluronic acid for 30 min at 37°C. After that time, the loading solution was aspirated, and 100 μl/well assay buffer (Hanks' balanced salt solution) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM probenecid, and 500 μM Brilliant Black (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI) was added. Concentrated solutions (1 mM) of NPS and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS were made in bidistilled water and kept at -20°C. Serial dilutions were carried out in Hanks' balanced salt solution/20 mM HEPES buffer containing 0.02% bovine serum albumin fraction V. After placing both plates (cell culture and master plate) into the fluorometric imaging plate reader Flex-Station II (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), fluorescence changes were measured at room temperature (≈25°C). On-line additions were carried out in a volume of 50 μl/well. The in vitro data were expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of at least four independent experiments made in duplicate. Maximum change in fluorescence, expressed in percentage of baseline fluorescence, was used to determine agonist response. Nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) allowed logistic iterative fitting of the resultant responses and the calculation of agonist potencies and maximal effects. Agonist potencies are given as pEC50 (the negative logarithm to base 10 of the molar concentration of an agonist that produces 50% of the maximal possible effect). [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS antagonist properties were evaluated in inhibition experiments, and the antagonist potency was expressed as pKB derived from the following equation: KB = IC50/((2 + ([A]/EC50)n)1/n - 1), where IC50 is the concentration of antagonist that produces 50% inhibition of the agonist response, [A] is the concentration of the agonist, EC50 is the concentration of agonist producing a 50% maximal response, and n is the Hill coefficient of the concentration-response curve to the agonist (Kenakin, 2004). Moreover, to investigate the type of antagonism exerted by [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS at NPSR, the classical Schild protocol (Schild, 1973) was performed, and in this case, the antagonist potency was expressed as pA2.

Animals. All experimental procedures adopted for in vivo studies complied with the standards of the European Communities Council directives (86/609/EEC) and national regulations (D.L. 116/92). Male Swiss mice (3–4 months old; weight, 30–38 g) and 129S6/SvEv Taconic NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) littermates (4–6 months; weight, 20–28 g) were used. They were housed in 425 × 266 × 155-mm cages (Tecniplast, Montreal, QC, Canada), under standard conditions (22°C, 55°C humidity, 12-h light/dark cycle, lights on at 7:00 AM) with food (MIL, standard diet; Morini, Reggio Emilia, Italy) and water ad libitum for at least 10 days before the experiments began. Each animal was used only once. NPS and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS were given intracerebroventricularly. Intracerebroventricular injections (2 μl/mouse) were given ether anesthesia under light (just sufficient to produce a loss of the righting reflex) into the left ventricle according to the procedure described by Laursen and Belknap (1986) and routinely adopted in our laboratory (Rizzi et al., 2001). All procedures were randomized across test groups.

Generation of NPSR(-/-) Mice. NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) littermates were obtained by mating heterozygous NPSR(+/-) 129S6/SvEv mice (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY), and all were genotyped using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to determine the target disruption of the NPSR gene. DNAs were prepared from tail biopsies using the Eazy Nucleic Acid Isolation Tissue DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA). One microliter of genomic DNA was added to a PCR reaction mix containing 3 mM MgCl2, deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (Promega, Madison, WI), and primers in a final concentration of 4 μg/ml. Three oligonucleotide primers were used. The first one was a forward primer specific to the endogenous NPSR locus [5′-CCTTATCCTCAAACCACGAAGTAT-3′]. The second one was a common reverse primer [5′-GTGGGTACATGAGAAGGTTAGGAG-3′], and the third one was a forward primer [5′-AAATGCCTGCTCTTTACTGAAGG-3′] specific to the targeting plasmid. The reagents were mixed in a Green GoTaq ThermoPol Reaction Buffer (Promega). GoTaq DNA Polymerase (Promega) (2.5 units/reaction) and an aliquot of water were added to bring the reaction mix to 50-μl total volume. The reaction was placed in a thermal cycler and heated to 94°C for 1 min. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 39 cycles as follows: 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Finally, the reaction was heated to 72°C for 2 min and then stored at 4°C. The reaction products were separated in 1% agarose by horizontal gel electrophoresis in Tris acetate-EDTA buffer, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV light.

Mouse Righting Reflex Recovery Test. The RR assay was performed according to the procedures described previously in detail (Rizzi et al., 2008). In brief, mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 15 mg/kg diazepam. When the animals lost the RR, they were placed in a plastic cage, and the time was recorded by an expert observer blind to drug treatments. Animals were judged to have regained the RR response when they could right themselves three times within 30 s. Sleeping time is defined as the amount of time between the loss and regaining of the RR; it was rounded to the nearest minute. The ability of NPS (0.1 nmol i.c.v.) and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (1 and 10 nmol i.c.v.) to modify the number (percentage) of animals responding to 15 mg/kg diazepam and their sleeping time (minutes) were evaluated. NPS and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS were administered 5 min before the injection of diazepam.

Drugs and Reagents. NPS and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS were synthesized according to published methods (Camarda et al., 2008) using Fmoc/tBu chemistry with a SYRO XP multiple peptide synthesizer (Syro-MultiSynTech, Bochum, Germany). Crude peptides were purified by preparative reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, and the purity was checked by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry using a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) and an ESI Micromass ZMD-2000 mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The vehicle used for injecting NPS and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS was 0.9% saline.

Terminology and Statistical Analysis. The pharmacological terminology adopted in this article is consistent with International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology recommendations (Neubig et al., 2003). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of n experiments/animal. For agonist and antagonist potencies, 95% confidence limits were given. Data were analyzed using the Student's t test, one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test, or the Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's test, as specified in the figure legends. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

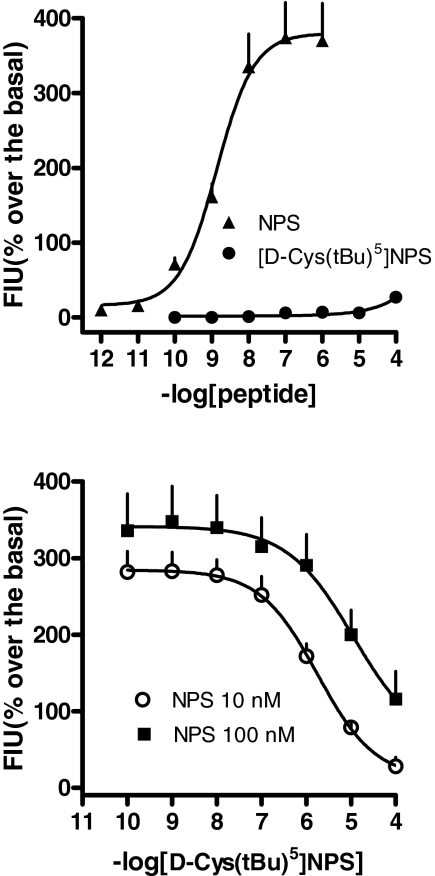

Calcium Mobilization Assay. In the calcium mobilization assay performed on HEK293mNPSR cells, NPS increased the intracellular calcium concentrations in a concentration-dependent manner, with pEC50 and Emax values of 8.86 (CL95%, 8.46–9.26) and 380 ± 50% over the basal, respectively (Fig. 1, top). [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS, up to concentrations as high as 100 μM, was found inactive (Fig. 1, top). Inhibition-response curves to [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (0.1 nM–100 μM) were then performed against the stimulatory effect of NPS at 10 and 100 nM, corresponding to submaximal and maximal concentrations, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, bottom, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS concentration-dependently inhibited 10 and 100 nM NPS effects, with pIC50 values of 5.75 and 4.64 (for the latter assuming a complete inhibition), respectively. A[d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS pKB value of 6.62 (CL95%, 6.40–6.84) was derived from these experiments.

Fig. 1.

Calcium mobilization assay performed on HEK293mNPSR cells. Concentration-response curves to NPS and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (top). Inhibition-response curve to [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (0.1 nM–100 μM) against the stimulatory effect of 10 and 100 nM NPS (bottom). Data are mean ± S.E.M. of four experiments.

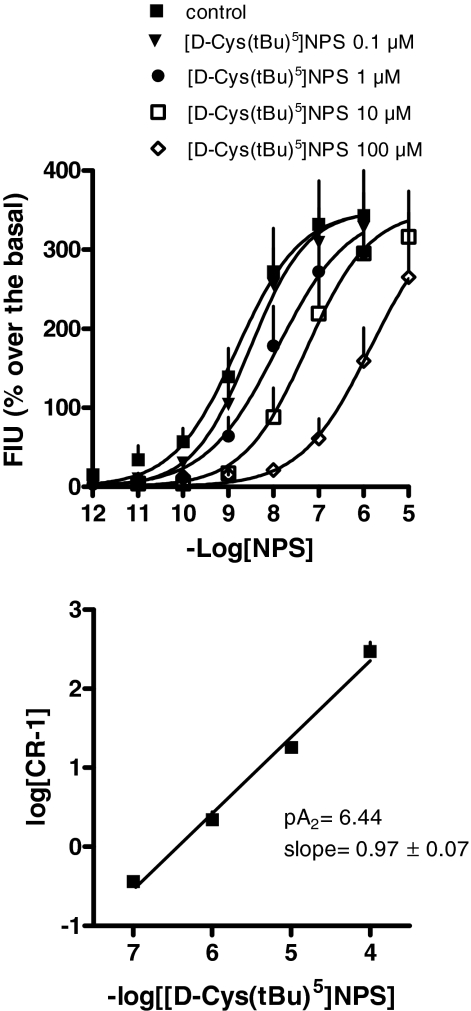

To get information on the nature of the antagonist action exerted by [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS, the classical Schild analysis was also performed. As depicted in Fig. 2, top, [d-Cys(tBu)5]-NPS, in the range 0.1 to 100 μM, did not have any effect per se but produced a rightward shift of the concentration-response curve to NPS in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas the curves remained parallel to the control and reached similar maximal effects. The corresponding Schild plot, which was linear (r2 = 0.99) with a slope of 0.97 ± 0.07, is shown in Fig. 2, bottom. The extrapolated pA2 value was 6.44.

Fig. 2.

Calcium mobilization assay performed on HEK293mNPSR cells. Concentration-response curve to NPS obtained in the absence (control) and in the presence of increasing concentrations of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (0.1–100 μM) (top); the corresponding Schild plot is shown at bottom. Data are mean ± S.E.M. of four experiments.

Finally, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS selectivity of action was investigated by challenging the peptide against a panel of G-protein-coupled receptors (Table 1). These include native muscarinic receptors expressed in HEK293 cells, native PAR-2 receptors expressed in A549 cells, and recombinant human NK-1, UT, and opioid receptors expressed in CHO cells. In these experiments, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS did not stimulate calcium mobilization up to 10 μM and did not modify the concentration-response curves to receptor agonists (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Selectivity profile of [D-Cys(tBu)5]NPS at seven different G-protein-coupled receptors Data are mean ± S.E.M. of three separate experiments performed in duplicate. The chimeric protein αqi5 (Coward et al., 1999) was used to force opioid receptors to couple with the calcium pathway.

|

Cell Lines

|

Receptor

|

Agonist

|

Control

|

[D-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (10 μM)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEC50 | Emax ± S.E.M. | pEC50 | Emax ± S.E.M. | |||

| % above baseline | % above baseline | |||||

| HEK293 | Native muscarinic | Carbachol | 5.60 (5.21–5.69) | 309 ± 31 | 5.44 (4.82–6.06) | 309 ± 33 |

| CHO | Recombinant hNK-1 | Substance P | 10.26 (9.88–10.64) | 122 ± 15 | 10.10 (9.51–10.69) | 110 ± 20 |

| CHO | Recombinant hUT | Urotensin-II | 8.31 (7.62–9.00) | 224 ± 21 | 8.37 (7.54–9.20) | 225 ± 23 |

| CHO-αqi5 | Recombinant hMOP | Dermorphin | 7.98 (7.85–8.11) | 186 ± 11 | 7.80 (7.16–8.44) | 194 ± 13 |

| CHO-αqi5 | Recombinant hDOP | [D-Pen2,D-Pen5]-enkephalin | 8.63 (8.41–8.84) | 169 ± 26 | 8.65 (8.52–8.78) | 155 ± 22 |

| CHO-αqi5 | Recombinant hKOP | Dynorphin A | 8.11 (7.72–8.50) | 143 ± 12 | 8.53 (8.00–9.06) | 144 ± 12 |

| A549 | Native hPAR-2 | SLIGKV-NH2 | 4.66 (4.43–4.89) | 449 ± 25 | 4.77 (4.31–5.23) | 433 ± 37 |

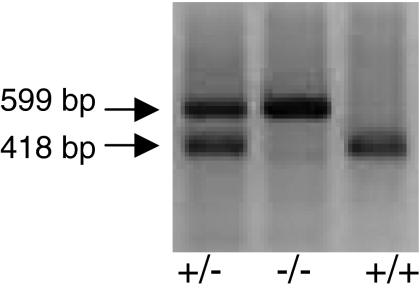

PCR Analysis of Tail Biopsy DNA from Offspring Obtained by Mating Heterozygous NPSR(+/-) Mice. All the results obtained in this study were performed using NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) littermates; all the mice were genotyped and divided in two experimental groups depending on the presence of different PCR products. As shown in Fig. 3, the PCR amplification of a 418-bp DNA fragment identifies a homozygous wild-type NPSR(+/+) mouse, whereas the 599-bp DNA fragment corresponds to a NPSR(-/-) mouse. Amplification of both DNA fragments is related to a heterozygous NPSR(+/-) mouse (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Typical PCR analysis of tail biopsies DNA from offspring obtained by mating heterozygous NPSR(+/-) mice. PCR product of 418 bp was from the homozygous wild-type mice [NPSR(+/+)]; a 599-bp DNA fragment was amplified from homozygous knockout mice [NPSR(-/-)]. The heterozygous NPSR(+/-) mice showed both the PCR products.

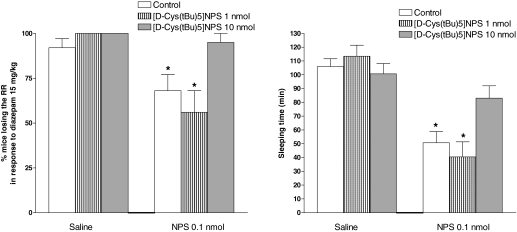

Righting Reflex Recovery Test. As shown in Fig. 4, intraperitoneal injection of diazepam at the hypnotic dose of 15 mg/kg produced loss of the RR in 92% of the mice, and approximately 105 min were needed to regain this reflex. NPS injected intracerebroventricularly at 0.1 nmol reduced the percentage of animals responding to diazepam to 58% and their sleeping time to approximately 50 min. On the contrary, the administration of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS at 1 and 10 nmol did not significantly modify the hypnotic effect of diazepam, either in terms of percentage of animals losing the RR or sleeping time. When 1 nmol [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS was coinjected with NPS, it did not significantly modify the action of the natural peptide; however, when the higher dose of 10 nmol was used, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS prevented the arousal-promoting effect of NPS (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Recovery of righting reflex in Swiss mice. Effects elicited by intracerebroventricularly injected NPS (0.1 nmol) and [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS (1–10 nmol) alone or coinjected on the percentage of animals losing the righting reflex in response to 15 mg/kg i.p. diazepam (left) and on their sleeping time (right). Sleeping time is defined as the amount of time between the loss and regaining of the righting reflex. Data are mean ± S.E.M. of 16 mice per group. *, p < 0.05 versus saline, according to Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's test (left) or one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons (right).

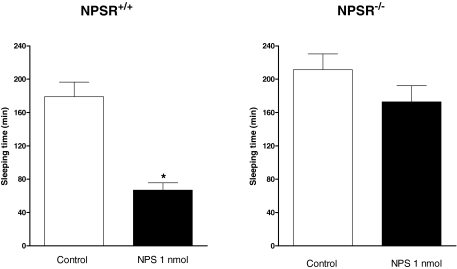

In a separate series of experiments, NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) mice were investigated for their phenotype and sensitivity to NPS in the RR assay. The intraperitoneal injection of diazepam at 15 mg/kg produced loss of the RR in 100% of both NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) mice, and 180 ± 18 and 211 ± 19 min were needed to regain this reflex in NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) mice, respectively (Fig. 5). In NPSR(+/+) mice, NPS injected intracerebroventricularly at the dose of 1 nmol did not modify the percentage of animals responding to diazepam; however, it clearly reduced their sleeping time to 67 ± 9 min. On the contrary, when tested in NPSR(-/-) mice, 1 nmol NPS failed to modify the hypnotic effect of diazepam (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Recovery of righting reflex in NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) mice. Effects elicited by 1 nmol i.c.v. injected NPS on the sleeping time of animals losing of the righting reflex in response to 15 mg/kg i.p. diazepam. Sleeping time is defined as the amount of time between the loss and regaining of the righting reflex. Data are mean ± S.E.M. of 10 to 12 mice per group. *, p < 0.05 versus saline, according to the Student's t test.

Discussion

The present findings demonstrate that [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS behaves as a pure, moderate potency, competitive, and selective NPSR antagonist. These features make [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS a useful tool for future studies on the roles played by the NPS/NPSR system in physiology and pathology. Moreover, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS will be adopted as a lead structure to develop more potent NPSR peptide antagonists. In addition, the present study provides converging in vivo evidence from both receptor antagonist and knockout studies demonstrating that the arousal-promoting action of NPS is solely because of selective NPSR activation.

The in vitro pharmacological features of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS were assessed in cells expressing the murine NPSR measuring intracellular calcium levels in a similar manner as we and others did in previous studies (Reinscheid et al., 2005; Roth et al., 2006; Tancredi et al., 2007; Camarda et al., 2008; Okamura et al., 2008). [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS at concentrations as high as 100 μM did not stimulate calcium mobilization in HEK293mNPSR cells but was able to completely inhibit, in a concentration-dependent manner, the stimulatory effect of NPS. These results demonstrate that [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS lacks efficacy and behaves as a pure NPSR antagonist. In inhibition-response curve experiments, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS antagonized NPS effects, with pIC50 values (5.75 versus 10 nM NPS, 4.64 versus 100 nM NPS) clearly influenced by the concentration of agonist, thus suggesting a competitive type of interaction (Kenakin, 2004). This was confirmed by classical Schild analysis where the peptide produced a concentration-dependent rightward shift of the concentration-response curves to NPS without modifying its maximal effects. The estimated potency of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS in the two series of experiments, namely Schild plot (pA2, 6.44) and inhibition experiments (pKB, 6.62), is virtually superimposable and allows the classification of this ligand as a moderate-potency, pure, and competitive antagonist.

Under the same experimental conditions, 10 μM [d-Cys(tBu)5]-NPS was found to be inactive both as agonist and antagonist at different G-protein-coupled receptors including muscarinic, opioid, NK-1, UT, and PAR-2 receptors. These results certainly allow the exclusion of the possibility that the antagonist action of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS versus NPS can be because of a nonspecific inhibitory effect on calcium signaling. However, the panel of receptors used is probably not enough for firmly classifying [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS as a selective NPSR antagonist. On the other hand, it is worthy of mention that [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS was generated by substituting a single residue into a 20-amino acid-long peptide characterized by high selectivity of action (Xu et al., 2004) and whose primary sequence is highly conserved among animal species (Reinscheid, 2007). These considerations make the possibility that [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS maintains the same high selectivity of action as the natural peptide extremely likely.

NPSR is expressed in several brain regions known to play a major role in the regulation of arousal (Xu et al., 2007), and NPS produces a robust arousal-promoting effect when administered supraspinally in rodents. In fact, in rat electroencephalographic studies, NPS given supraspinally increased the amount of wakefulness and decreased slow-wave sleep and rapid eye movement sleep (Xu et al., 2004). These experiments and findings were independently replicated in a different laboratory (Ahnaou et al., 2006). In addition, in mice, NPS administration mimicked the arousal-promoting action of caffeine by reducing the percentage of animals losing the RR in response to a hypnotic dose (15 mg/kg) of diazepam and markedly decreasing the sleeping time in those animals responding to the benzodiazepine (Rizzi et al., 2008). Thus, we used the mouse RR assay for investigating the in vivo action of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS. For this study, the NPS dose of 0.1 nmol was selected based on previous dose-response studies (Rizzi et al., 2008) as the lowest NPS dose producing statistically significant effects. In line with previous findings, 0.1 nmol NPS produced a clear arousal-promoting effect in the mouse RR assay. [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS tested at 1 nmol was found inactive per se and versus the effect elicited by NPS. At 10-fold higher doses, [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS did not modify per se the hypnotic effect of diazepam but fully prevented the arousal-promoting action of NPS. This result confirmed in vivo the antagonistic properties of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS. The in vivo dose range of activity of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS perfectly matches its in vitro potency at NPSR. In fact, the peptide was active when tested versus NPS in a 100:1 but not 10:1 dose ratio, and its in vitro antagonist potency (≈6.5) is 100-fold lower than NPS agonist potency (≈8.5).

The neurobiological implications of these experiments are 2-fold. First, with the use of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS, we demonstrated that the arousal-promoting effects of NPS are exclusively because of NPSR activation. This result is in line with previous reports about the stimulatory effect of NPS on locomotor activity using the nonpeptide antagonist SHA 68 (Okamura et al., 2008) and the peptide partial agonist [Ala3]NPS (Calo et al., 2006). Second, the lack of effect of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS per se at doses able to prevent the action of exogenously applied NPS suggests that endogenous NPS signaling is not activated under the present experimental conditions. This observation is at variance to the orexin system, a well known peptidergic arousal-promoting system (Bingham et al., 2006); in fact, orexin receptor antagonists not only prolonged barbiturate sleeping time in rats (Kushikata et al., 2003) and emergence from general anesthesia in mice (Kelz et al., 2008) but are also able per se to promote sleep in rats, dogs, and humans (Brisbare-Roch et al., 2007). It is clear that further studies are needed to firmly understand the role of the endogenous NPS/NPSR system in the regulation of wakefulness and sleep functions.

NPSR knockout mice were recently generated (Allen et al., 2006) to investigate the possible involvement of this receptor in respiratory diseases such as asthma (Laitinen et al., 2004). However, the elegant study performed by Allen et al. (2006) failed to support a direct contribution of NPSR to asthma pathogenesis. No data from receptor knockout studies are yet available regarding the involvement of NPSR in the control of central functions. Here, we used NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) mice for investigating their phenotype and sensitivity to NPS in the RR assay. These mice were more sensitive than Swiss mice to the hypnotic effect of diazepam, as suggested by the huge difference in sleeping time induced by the benzodiazepine (approximately 200 and 100 min, respectively) and by the fact that NPS reduced the percentage of animals losing the RR in response to diazepam in Swiss but not in NPSR(+/+) mice. This diverse diazepam sensitivity can be due to the difference in genetic background (Swiss versus 129S9/Sv/Ev) and/or age (3–4 versus 4–6 months). Results obtained from receptor knockout studies perfectly match those from antagonist studies. In fact, no differences were observed between NPSR(+/+) and NPSR(-/-) mice in terms of diazepam-induced sleeping time, and this parallels the lack of effect of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS per se in the RR test, corroborating the proposal that, under the present experimental conditions, the endogenous NPS/NPSR system is not activated. Moreover, the supraspinal administration of NPS reduced diazepam-induced sleeping time in NPSR(+/+) but not in NPSR(-/-) mice, and this parallels the lack of effect of NPS in the presence of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS, corroborating the proposal that the mechanism by which NPS promotes arousal is the selective activation of the NPSR protein.

In conclusion, the present study describes the in vitro and in vivo pharmacological features of [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS and demonstrates that this molecule behaves as a moderate potency, pure, competitive, and selective NPSR antagonist. Moreover, using this tool together with receptor knockout mice studies, it has been demonstrated that the arousal-promoting action of NPS is because of the selective activation of the NPSR protein. In the near future, the use of peptide (i.e., [d-Cys(tBu)5]NPS) and nonpeptide (i.e., SHA 68, Okamura et al., 2008) NPSR antagonists together with NPSR(-/-) animals will allow for a more detailed investigation of the NPS/NPSR system in several important central functions, such as sleep/wakefulness cycles, the response to stress, anxiety, and regulation of food intake. This information will be crucial for validating the therapeutic potential of new drugs acting as NPSR ligands.

This work was supported by the University of Ferrara [FAR Grant]; the Italian Ministry of University [Grant PRIN 2006]; and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health [Grant MH71313].

V.C. and A.R. contributed equally to this work.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.108.143867.

ABBREVIATIONS: NPS, neuropeptide S; NPSR, NPS receptor; SHA 66, 3-oxo-1,1-diphenyl-tetrahydro-oxazolo[3,4-a]pyrazine-7-carboxylic acid benzylamide; SHA 68, 3-oxo-1,1-diphenyl-tetrahydro-oxazolo[3,4-a]pyrazine-7-carboxylic acid 4-fluoro-benzylamide; HEK, human embryonic kidney; HEK293mNPSR, HEK293 cells expressing the mouse NPSR; RR, righting reflex recovery; NPSR(-/-), NPSR knockout mice; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary.

References

- Ahnaou A, Drinkenburg W, Huysmans H, Heylen A, Steckler T, and Dautzenberg F (2006) Differential roles of hypothalamic neuropeptides in sleep-wake modulation in rats. Soc Neurosci Abstr 32 458.1/CC11. [Google Scholar]

- Allen IC, Pace AJ, Jania LA, Ledford JG, Latour AM, Snouwaert JN, Bernier V, Stocco R, Therien AG, and Koller BH (2006) Expression and function of NPSR1/GPRA in the lung before and after induction of asthma-like disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291 L1005-L1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B, Fernette B, and Stricker-Krongrad A (2005) Peptide s is a novel potent inhibitor of voluntary and fast-induced food intake in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 332 859-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier V, Stocco R, Bogusky MJ, Joyce JG, Parachoniak C, Grenier K, Arget M, Mathieu MC, O'Neill GP, Slipetz D, et al. (2006) Structure-function relationships in the neuropeptide S receptor: molecular consequences of the asthma-associated mutation N107I. J Biol Chem 281: 24704-24712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham MJ, Cai J, and Deehan MR (2006) Eating, sleeping and rewarding: orexin receptors and their antagonists. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev 9 551-559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbare-Roch C, Dingemanse J, Koberstein R, Hoever P, Aissaoui H, Flores S, Mueller C, Nayler O, van Gerven J, de Haas SL, et al. (2007) Promotion of sleep by targeting the orexin system in rats, dogs and humans. Nat Med 13 150-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calo G, Roth A, Marzola E, Rizzi A, Arduin M, Trapella C, Corti C, Vergura R, Martinelli P, Salvadori S, et al. (2006) Structure activity studies on Neuropeptide S: identification of the amino acid residues crucial for receptor activation. Soc Neurosci Abstr 32 726.18/D56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarda V, Trapella C, Calo G, Guerrini R, Rizzi A, Ruzza C, Fiorini S, Marzola E, Reinscheid RK, Regoli D, and Salvadori S (2008) Synthesis and biological activity of human neuropeptide S analogues modified in position 2. J Med Chem 51 655-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Cannella N, Fedeli A, Cippitelli A, Calo G, Massi M, and Guerrini R (2006) Inhibition of palatable food intake by Neuropeptide S is reversed by its analogue [Ala3]hNPS. Soc Neurosci Abstr 32 809.7/O15. [Google Scholar]

- Coward P, Chan SD, Wada HG, Humphries GM, and Conklin BR (1999) Chimeric G proteins allow a high-throughput signaling assay of Gi-coupled receptors. Anal Biochem 270 242-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jüngling K, Seidenbecher T, Sosulina L, Lesting J, Sangha S, Clark SD, Okamura N, Duangdao DM, Xu YL, Reinscheid RK, et al. (2008) Neuropeptide S-mediated control of fear expression and extinction: role of intercalated GABAergic neurons in the amygdala. Neuron 59 298-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelz MB, Sun Y, Chen J, Cheng Meng Q, Moore JT, Veasey SC, Dixon S, Thornton M, Funato H, and Yanagisawa M (2008) An essential role for orexins in emergence from general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 1309-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T (2004) A Pharmacology Primer, Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Kushikata T, Hirota K, Yoshida H, Kudo M, Lambert DG, Smart D, Jerman JC, and Matsuki A (2003) Orexinergic neurons and barbiturate anesthesia. Neuroscience 121 855-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen T, Polvi A, Rydman P, Vendelin J, Pulkkinen V, Salmikangas P, MäkeläS, Rehn M, Pirskanen A, Rautanen A, et al. (2004) Characterization of a common susceptibility locus for asthma-related traits. Science 304 300-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen SE and Belknap JK (1986) Intracerebroventricular injections in mice: some methodological refinements. J Pharmacol Methods 16 355-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard SK, Dwyer JM, Sukoff Rizzo SJ, Platt B, Logue SF, Neal SJ, Malberg JE, Beyer CE, Schechter LE, Rosenzweig-Lipson S, et al. (2008) Pharmacology of neuropeptide S in mice: therapeutic relevance to anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 197 601-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubig RR, Spedding M, Kenakin T, and Christopoulos A (2003) International Union of Pharmacology Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug Classification: XXXVIII. Update on terms and symbols in quantitative pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 55 597-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimi M (2006) Centrally administered neuropeptide S activates orexin-containing neurons in the hypothalamus and stimulates feeding in rats. Endocrine 30 75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N, Habay SA, Zeng J, Chamberlin AR, and Reinscheid RK (2008) Synthesis and pharmacological in vitro and in vivo profile of 3-oxo-1,1-diphenyltetrahydro-oxazolo[3,4-a]pyrazine-7-carboxylic acid 4-fluoro-benzylamide (SHA 68), a selective antagonist of the neuropeptide S receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325 893-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri L, Luccini E, Romei C, and Salvadori S (2008) Neuropeptide s modulates neurotransmitter release from mouse frontal cortex nerve terminals, in Europen Opioid Conference with European Neuropeptide Club Joint Meeting; 8–11 April 2008; Ferrara, Italy. p 50.

- Reinscheid RK (2007) Phylogenetic appearance of neuropeptide S precursor proteins in tetrapods. Peptides 28 830-837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinscheid RK, Xu YL, Okamura N, Zeng J, Chung S, Pai R, Wang Z, and Civelli O (2005) Pharmacological characterization of human and murine neuropeptide S receptor variants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 315 1338-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi A, Bigoni R, Marzola G, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, Regoli D, and Calò G (2001) Characterization of the locomotor activity-inhibiting effect of nociceptin/orphanin FQ in mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 363 161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi A, Vergura R, Marzola G, Ruzza C, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, Regoli D, and Calo G (2008) Neuropeptide S is a stimulatory anxiolytic agent: a behavioural study in mice. Br J Pharmacol 154 471-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth AL, Marzola E, Rizzi A, Arduin M, Trapella C, Corti C, Vergura R, Martinelli P, Salvadori S, Regoli D, et al. (2006) Structure-activity studies on neuropeptide S: identification of the amino acid residues crucial for receptor activation. J Biol Chem 281 20809-20816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild HO (1973) Receptor classification with special reference to beta adrenergic receptors, in Drug receptors pp 29-36, University Park Press, Baltimore, MD.

- Smith KL, Patterson M, Dhillo WS, Patel SR, Semjonous NM, Gardiner JV, Ghatei MA, and Bloom SR (2006) Neuropeptide S stimulates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and inhibits food intake. Endocrinology 147 3510-3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tancredi T, Guerrini R, Marzola E, Trapella C, Calo G, Regoli D, Reinscheid RK, Camarda V, Salvadori S, and Temussi PA (2007) Conformation-activity relationship of neuropeptide S and some structural mutants: helicity affects their interaction with the receptor. J Med Chem 50 4501-4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale G, Filaferro M, Ruggieri V, Pennella S, Frigeri C, Rizzi A, Guerrini R, and Calò G (2008) Anxiolytic-like effect of neuropeptide s in the rat defensive burying. Peptides 29 2286-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YL, Gall CM, Jackson VR, Civelli O, and Reinscheid RK (2007) Distribution of neuropeptide S receptor mRNA and neurochemical characteristics of neuropeptide S-expressing neurons in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 500 84-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YL, Reinscheid RK, Huitron-Resendiz S, Clark SD, Wang Z, Lin SH, Brucher FA, Zeng J, Ly NK, Henriksen SJ, de Lecea L, and Civelli O (2004) Neuropeptide S: a neuropeptide promoting arousal and anxiolytic-like effects. Neuron 43 487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]