Abstract

Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) methylates histone H3 tails at lysine 27 and is essential for embryonic development. The three core components of PRC2, Eed, Ezh2, and Suz12, are also highly expressed in embryonic stem (ES) cells where they are postulated to repress developmental regulators and thereby prevent differentiation to maintain the pluripotent state. We performed gene expression and chimera analyses on low and high passage Eednull ES cells to determine whether PRC2 is required for the maintenance of pluripotency. We report here that, although developmental regulators are overexpressed in Eednull ES cells, both low and high passage cells are functionally pluripotent. We hypothesize that they are pluripotent because they maintain expression of critical pluripotency factors. Given that EED is required for stability of EZH2, the catalytic subunit of the complex, these data suggest that PRC2 is not necessary for the maintenance of the pluripotent state in ES cells. We propose a positive-only model of embryonic stem cell maintenance, where positive regulation of pluripotency factors is sufficient to mediate stem cell pluripotency.

Keywords: embryonic stem cell, pluripotent, epigenetics, gene expression, embryo

Introduction

One of the earliest and most dynamic mechanisms of epigenetic gene regulation is covalent modification of histone tails by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2). PRC2 is comprised of three core components, EED, EZH2, and SUZ12. EZH2 is a histone methyltransferase and the catalytic subunit of the PRC2 complex. While the functions of EED and SUZ12 remain unknown, all three core components are minimally required for robust PRC2 activity1. EED, however, is required for the stability of the EZH2 and SUZ12 proteins and global H3K27 methylation2.

PRC2 methylates histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27). Trimethylated H3K27 (H3K27me3) recruits Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1)3, which in turn mediates chromatin condensation4, and may even recruit DNA methyltransferases5 to specific genes during development. This process leads to transcriptional silencing and inheritance of the silenced state to daughter cells6, 7. PRC2, through this heritable mechanism of epigenetic gene repression, functions in the maintenance of cellular identity in hematopoietic stem cells8, 9, differentiating trophoblast cells10, embryonic mesoderm11, and cancer stem cells12, 13. Reports also implicate PRC2 in the maintenance of the pluripotent state in embryonic stem cells14-17.

PRC2 binds to and represses the transcription of many developmental regulators that are markers of differentiated cell lineages in both mouse and human ES cells15, 16, 18. Additionally, H3K27me3 colocalizes with histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), a chromatin modification associated with active genes, in bivalent domains at several promoters that mark genes that are silenced but poised for activation15, 19, 20. Remarkably, about 50% of bivalent domains coincide with binding sites for OCT4, NANOG, or SOX2, transcription factors required for maintaining pluripotency in ES cells. OCT4 itself, was recently shown to bind to and activate the EED promoter in mouse ES cells17. These data point to an attractive hypothesis where ES cell identity is maintained by a careful balance between PRC2-mediated silencing and gene expression mediated by the transcription factors, OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2.

We wanted to determine whether PRC2 was required to maintain ES cell identity and the pluripotent state by comparing gene expression and functional measures of pluripotency in low and high passage Eednull ES cells. We report here that, although developmental regulators are overexpressed in Eednull ES cells, both low and high passage cells are functionally pluripotent. We hypothesize that they are pluripotent because they maintain expression of critical pluripotency factors and do not respond to differentiation signals. These data suggest that PRC2, and perhaps epigenetic silencing, is not necessary for maintaining the pluripotent state in embryonic stem cells. Rather, PRC2 may be important for transitions in cell fate (differentiation) and maintenance of multipotency in later progenitor cells. We propose a positive-only model of embryonic stem-cell maintenance, where positive regulation of pluripotency factors is sufficient to mediate stem cell pluripotency.

Materials and Methods

ES cells and culture

Eednull ES cell lines and their wild-type sibling ES lines were derived from the Eed17Rn53354SB strain of mice carrying the ROSA26 β-geo transgene21. These ES cells carry a homozygous point mutation in the Eed gene that results in a functionally null allele22, as well as a constitutively expressed β-geo gene that serves as a reporter and a selectable marker. Images and a detailed description of mutant ES cell morphology can be found in Figure S1.

Eednull ES cells were maintained on irradiated murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) using standard ES culture conditions. Specifically, cells were grown in ES media, consisting of MEM-α (Invitrogen) medium with 15% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) supplemented with non-essential amino acids, glutamate, sodium pyruvate, β-mercaptoethanol, pen-strep, and LIF. MEF conditioned media was also produced by growing irradiated MEFs in ES media for 48 hours and collecting the media. To generate RNA, ES cells were passaged onto a gelatinized plate and cultured with 50% MEF-conditioned media/50% ES media.

To generate high pass ES cells, both Eednull and wild-type ES cells were cultured for 25 additional passages. Low pass refers to ES cells at pass 7 (p7), while high pass refers to ES cells at pass 32 (p32) or higher. Eednull ES cells can be maintained with good morphology (Fig. S1). All ES lines used in this study were feeder and LIF dependent. For microarray analysis, p32 cells were used and for chimera analysis, p35 cells were used for high pass cultures.

Immunocytochemistry

ES cells were cultured on gelatin-coated coverslips with feeders as described above. Coverslips were treated with CSK buffer (100 mM NaCl, 300 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM PIPES [pH 6.8]) containing 0.5% Triton-X, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/1X PBS, and stored in 70% ethanol. Coverslips were washed in 1× PBS and incubated in a humid chamber with blocking buffer (1× PBS, 5% goat serum, 0.2% Tween-20, and 0.2% fish skin gelatin). Blocked samples were incubated with primary antibodies (anti-1mH3K27 [Upstate], anti-2mH3K27 [Upstate], anti-3mH3K27[Upstate], anti-OCT4[Santa Cruz], anti-NANOG[Santa Cruz])diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer. The coverslips were then washed in 1× PBS/0.2% Tween-20, blocked again in blocking buffer, and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (Goat anti-Rabbit Alexa 594, Goat anti-Rabbit Alexa 488, Goat anti-Mouse Alexa 594, or Goat anti-Mouse Alexa 488 [Molecular Probes]). Coverslips were washed in 1× PBS/0.2% Tween-20 and mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Stained slides were visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Microarray analysis

Eednull and wild-type ES cells were cultured in triplicate for microarray analysis. Samples were harvested and RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was further purified using RNeasy columns (QIAGEN). The quality of the RNA was confirmed prior to labeling using the Agilent Nano RNA Lab-on-a-Chip and the 2100 Bioanalyzer.

RNAs were combined with RNA spike-in control RNAs from the RNA Spike-In kit (two color, Agilent) and labeled using the RNA Low-Input Linear Amp Kit PLUS (two color, Agilent) with Cyanine 3-CTP (NEN) and Cyanine 5-CTP (NEN) dyes. The labeled RNAs were again purified using RNeasy columns (QIAGEN). Quality and labeling fidelity of the labeled RNAs was assessed using the Nano RNA Lab-on -a-Chip and the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent).

The following head-to-head experiments were performed using both dye directions (Cy3 vs Cy5 and then swapped). Low pass mutant versus low pass wild-type and high pass mutant versus high pass wild-type for each of the three replicates. In total, 12 microarrays were completed. Labeled RNAs were hybridized to the 4X44K mouse whole genome oligo microarray for at least 17 hours in Hi-RPM hybridization buffer (Agilent), according to manufacturer's protocols. Microarray slides were washed according to manufacturer's instructions and scanned on an Agilent microarray scanner. The microarray images were interpreted using Feature Extraction 9.5 software and further normalized using GeneSpring GX software. Default normalizations were performed that included Lowess normalization and dye swap transformation on appropriate arrays. Data were averaged only for the 3 replicates for any one dye direction. The dye swaps verified that the data did not suffer from dye bias.

Interpretation of microarray data

To identify genes overexpressed in Eednull ES cells, GeneSpring GX was used to sort genes in which the expression level of mutant relative to wild-type ES cells was greater than 2.0 in at least 6 of 12 instances. This would take into account both low and high pass comparisons, but assure that the results were technically repeatable. Correlation of H3K27me3 bound genes and overexpressed genes was determined by merging the list of overexpressed genes with the chromatin structure status of the promoters included in the supplementary data from Mikkelsen et al20.

Graphs comparing expression levels for developmental regulators and pluripotency genes were performed from the average of 3 technical replicates. All unique transcripts representing individual genes were included in the analysis. The data were plotted using the graph function of Excel. Error bars shown represent the standard error from the three technical replicates.

Real-time RT-PCR

Samples were prepared for real-time RT-PCR by pooling 3 wells each of low pass wild-type, high pass wild-type, low pass Eednull, and high pass Eednull ES cells, and harvesting RNA using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). RNAs were purified using RNeasy columns (QIAGEN). Two samples from each condition were provided for RT-PCR analysis. Real time RT-PCR was carried out on the RNA samples by Dr. Hyung-suk Kim in the Animal Clinical Chemistry and Gene Expression Facility at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill using Taqman technology (Applied Biosystems).

Generation and analysis of chimeras

Chimeric embryos were generated by the Animal Models Core at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We provided the core facility with either low pass or high pass ES cells that were grown on a MEF feeder layer for 48 hours and harvested by trypsinization. The Animal Models Core performed blastocyst injections using standard procedures. Pregnant females were dissected at 9.5, 10.5, or 12.5 dpc, where the date of blastocyst injection was considered as 3.5 dpc. Embryos were dissected in 1X PBS and fixed with 0.2% glutaraldehyde. Embryos were processed for XGal staining with ferric salts. Stained embryos were rinsed 3 times in 1× PBS, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and cleared using a glycerol gradient. Following photography, embryos were embedded in paraffin or OCT for sectioning. Embryos prepared for paraffin sections were dehydrated through an ethanol gradient and incubated with xylenes and permeating paraffin prior to embedding in paraffin. Paraffin embedded embryos were sectioned at 8 μM, deparaffinized, and counterstained with nuclear fast red before dehydration and mounting. Embryos prepared for frozen sections were cryoprotected using a sucrose gradient and OCT prior to embedding in OCT and freezing. Cryosections were 10 μM and were not counterstained prior to dehydration and mounting.

Results

Eednull ES cells retain H3K27 monomethylation

Our previous observation that Eednull ES cells lacked H3K27me1, me2, and me3 pertained to high passage Eednull ES cells2. We repeated the immunocytochemistry using antibodies specific for each of the three forms of H3K27 methylation on low and high passage Eednull ES cells to confirm this observation. Surprisingly, we found that H3K27me1 was readily detectable in low passage Eednull ES cells but not in high passage mutant ES cell lines (Fig. 1A & B). Figure 1A shows wild-type along with low and high pass Eed mutant ES cells stained with an antibody against H3K27me1. The loss of H3K27me1 was observed in two independent high passage Eednull ES cell lines (data not shown), as well as cells newly passaged for these experiments, indicating that loss of H3K27me1 was not an artifact of clonal variation. Figure 1B shows Eednull ES cells at a low passage number, stained with polyclonal antibodies against H3K27me1, 2me, and 3me. DAPI stains in the right panel identify the ES cell colony. Both low and high passage Eednull ES cells lack H3K27me2 and me3, consistent with previous reports.

Figure 1. H3K27 methylation in low pass Eednull ES cells.

(A.)Wild-type, low pass Eednull, and high pass Eednull ES cells were stained with an antibody against H3K27me1. Monomethylation is robust in wild-type ES cells and detectable in low pass Eednull ES cells, but absent in high pass mutant ES cells. (B.) Low pass Eednull ES cells were stained with antibodies against H3K27me1, me2, and me3. Low pass mutant ES cells stain positively for H3K27me1, but not for H3K27me2 or me3. Positively staining feeder cells serve as internal controls. Corresponding gray-scale images of DAPI stains are shown to the right.

Promoters of genes overexpressed in Eednull ES cells are bound by PRC2

Boyer et al. observed spontaneous differentiation in cultures of high pass Eednull ES cells18, supporting their hypothesis that ES cell identity is maintained, in part, by PRC2-mediated gene repression. Although we do not observe spontaneous differentiation using the same Eednull ES cells, we nonetheless wondered whether the presence of H3K27me1 in low passage Eednull ES cells supports self-renewal of pluripotent ES, and whether pluripotency is lost concurrent with loss of H3K27me1 in high passage cell lines. We used microarray expression analyses to assess changes in gene expression between low and high passage Eednull ES cells. We performed head-to-head expression experiments between low and high passage Eednull ES cells using passage-matched wild-type ES cells as controls. We assayed 41,267 unique transcripts, and found that 351 transcripts were upregulated more than 2-fold in high passage Eednull ES cells over low passage mutant ES cells. This number compares to the 295 transcripts that were upregulated more than 2-fold between high passage and low passage wild-type controls. These data suggest that the absence of H3K27me1 plays a minor role in global gene expression in Eed mutant ES cells.

PRC2 is purported to maintain pluripotency through repression of developmental regulators 16, 18, 23, 24. We wondered whether we could detect previously observed changes in gene expression between mutant and wild-type Eednull ES cells. We used microarray expression analysis to directly compare passage-matched Eednull and wild-type ES cells. We compared low passage mutant and wild-type ES cells, as well as high passage mutant and wild-type ES cells. In all, 2,037 transcripts, or 4.9% of the transcripts represented on the microarray, were determined to be upregulated by 2-fold or more in low and/or high pass Eednull ES cells. Only 106 of the 2,037 genes were overexpressed in high passage versus low passage Eednull ES cells, reinforcing the lack of large-scale differences between low and high pass mutant ES cells.

Data using single molecule-based sequencing technology for profiling histone modifications identified promoters containing H3K27me3, either alone or in a bivalent domain with the H3K4me3 modification in mouse ES, neural precursor (NPC), or embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells20. We correlated our expression data with these histone modification profiles, and found that 27% of the promoters modified with H3K27me3 or the bivalent marks in ES cells were upregulated by 2-fold or more in Eednull ES cells. Transcription factors required for the expression of some H3K27me3 bound genes may not be present in ES cells, and may explain why all PRC2 bound promoters are not activated in Eed mutant ES cells. Only 6% of promoters containing H3K27me3 alone are upregulated in Eednull ES cells, suggesting that an activating chromatin modification is largely required for expression of PRC2 silenced genes. These data are summarized in Table S1.

Of the 2,037 transcripts overexpressed in Eednull ES cells, 747 transcripts, representing almost 37% of all overexpressed transcripts, harbor bivalent promoters in ES cells. When we considered the histone modification profiles of the upregulated genes in lineage-committed cells, we found that 3% and 16% of upregulated genes were marked by bivalent promoters in NPCs and MEFs, respectively. These data are summarized in Table S2. All overexpressed transcripts are not marked with H3K27me3, suggesting that many transcripts overexpressed in Eednull ES cells are not directly regulated by PRC2 and may be secondary effects.

We then identified developmental regulators that were previously shown to be marked by H3K27me3 and upregulated by real-time PCR18 in our microarray data. Consistent with previous results, Gata genes that are Polycomb bound (Gata3, Gata4, and Gata6) were upregulated in mutant ES cells, but genes not bound by Polycomb (Gata1 and Hprt) had expression levels similar to wild-type ES cells (Fig. 2A). Three unique Gata6 transcripts were represented on the microarray. Interestingly, one of these is not upregulated in mutant ES cells, suggesting that the particular splice form may be regulated by tissue- or developmental stage-specific splicing that does not occur in ES cells. Many other Polycomb-bound developmental regulators were also found to be upregulated in Eednull ES cells (Fig. 2 B,C). Additionally, we found that expression levels of these genes were lower in low pass ES cells (Fig. 2B), and higher in high pass ES cells (Fig. 2C). These data support the previous finding that PRC2 is required for the repression of important developmental regulators in ES cells.

Figure 2. Developmental regulators are aberrantly expressed in Eednull ES cells.

Multiple listings for the same gene indicate independent transcripts represented on the microarray, and may represent alternate splice forms. A horizontal black line on each graph indicates a value of 1, indicating that mutant and wild-type ES cells have the same expression levels. Error bars indicate standard error calculated from 3 technical replicates. (A.) Microarray data reveals that Polycomb-bound Gata genes (Gata3, Gata4, and Gata6) show increased expression in Eednull ES cells. Gata1 and Hprt, which are not Polycomb bound are shown as controls. Gray bars represent low pass and black bars represent high pass Eednull ES cells. (B.) Microarray data from low pass Eednull ES cells show an increase in expression compared to wild-type ES cells for many Polycomb bound developmental regulators. These genes were also surveyed by Boyer et al18. (C.) Microarray data from high pass Eednull ES cells shows a further increase in expression levels for the same genes shown in B.

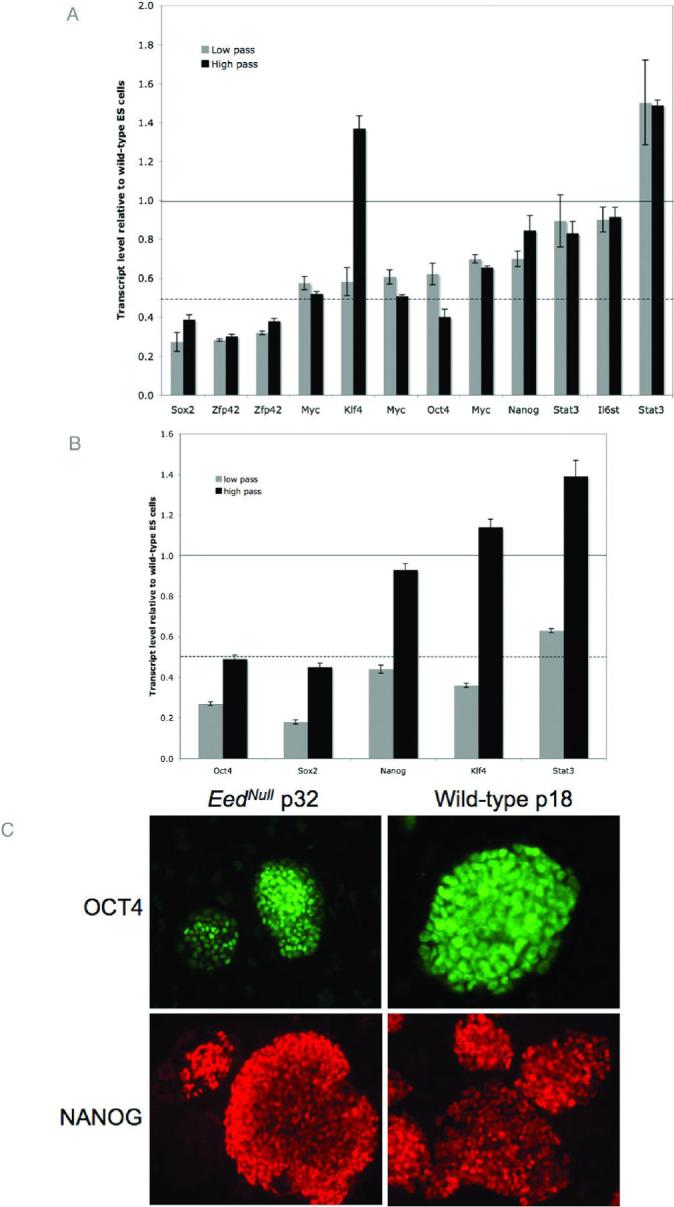

Expression of pluripotency genes in Eednull ES cells

Pluripotency is partly determined by positive regulation of a transcriptional program of expression conducive to maintaining the pluripotent state. The transcription factors, OCT4, SOX2, or NANOG are required to maintain the pluripotent state. Embryos lacking these proteins fail to maintain an inner cell mass, and ES cells lacking these factors cannot be derived25-27.

We assessed expression levels of previously known pluripotency factors in low and high passage Eednull ES cells to determine whether they are expressed in mutant ES cells. Figure 3A shows the microarray expression levels of known pluripotency factors in low and high pass Eednull ES cells relative to wild-type, passage-matched counterparts. Real-time PCR was used to verify the expression levels of some of these genes (Fig. 3B). We also analyzed protein expression using immunocytochemistry for OCT4 and NANOG (Fig. 3C). Most of the known pluripotency factors show reduced expression in mutant ES cells compared to wild-type ES cells (Fig. 3A & B), however, only Sox2, Zfp42, and Oct4 in high passage cells are expressed at levels less than 50% of wild-type levels, denoted by the dotted line. ES cells were cultured for 48 hours off of feeder cells prior to collecting RNA. Since Eednull ES cells are feeder dependent, reduced levels of pluripotency factors may reflect early differentiation resulting from feeder free culture conditions. Supporting this notion, immunocytochemistry for OCT4 on cells maintained on feeders showed intense staining in mutant ES cells, similar to their wild-type counterparts.

Figure 3. Expression of pluripotency factors in Eednull ES cells.

Multiple listings for the same gene indicate independent transcripts represented on the microarray and may represent alternate splice forms. Horizontal black lines indicate a value of 1, where mutant and wild-type ES cells have the same expression levels. Dashed black lines represent a value of 0.5, where mutant cells have half of the expression level as wild-type counterparts. (A.) The relative expression levels of several pluripotency markers in low (gray bars) and high (black bars) pass Eednull ES cells was determined by microarray analysis. While most factors have lower expression levels than wild-type ES cells, gene expression is maintained. With the exception of Klf4, low and high pass mutant cells have similar expression levels. Error bars indicate standard error calculated from 3 technical replicates. (B.) Real-time RT-PCR verification of selected genes represented in panel A shows that expression levels are reproducible. Real-time RT-PCR was carried out in duplicate on RNA generated from pooled cell samples (3 different samples per pool). Error bars represent standard error from 2 replicate pools. (C.) Wild-type and high pass Eednull ES cells were stained with antibodies against OCT4 and NANOG. Robust staining for is observed for both factors. Corresponding DAPI images are found in Figure S2.

Many of the pluripotency proteins mentioned above are transcription factors whose down-stream targets are the real effectors of self-renewal. Expression profiles of murine ES cells have been correlated with functional measures of pluripotency, such as the ability to form all germ layers in embryoid bodies and the ability to contribute to chimeric animals, to identify genes that mediate self-renewal28. We identified these genes in our microarray data (Figure 4A). Real-time PCR verification of data from fourz of the genes is shown in Figure 4B. Eednull ES cells maintain expression levels that are greater than or equal to expression levels in wild-type ES cells for most of the genes assayed. Wild-type expression levels are indicated by a relative expression level of 1.0, and are depicted by a black line. For most transcripts, low pass Eednull ES cells show higher expression levels than high pass mutant ES cells, however, high pass mutant ES cells maintain expression at wild-type levels or higher for most genes. These data suggest that although pluripotency-related transcription factors have reduced expression in Eednull ES cells, the expression profile of downstream genes that actually correlate with functional measures of pluripotency are not reduced.

Figure 4. Expression of downstream mediators of pluripotency.

(A.) Relative expression levels for transcripts identified by Palmqvist et al.28 as being closely correlated with functional pluripotency in low (yellow) and high (red) pass Eednull ES cells. Most genes are expressed at wild-type levels or higher in mutant ES cells. (B.) Real-time RT-PCR verification of selected genes represented in panel A. Real-time RT-PCR was carried out in duplicate on RNA generated from pooled cell samples (3 different samples per pool). Error bars for panel D represent standard error from 2 replicate pools.

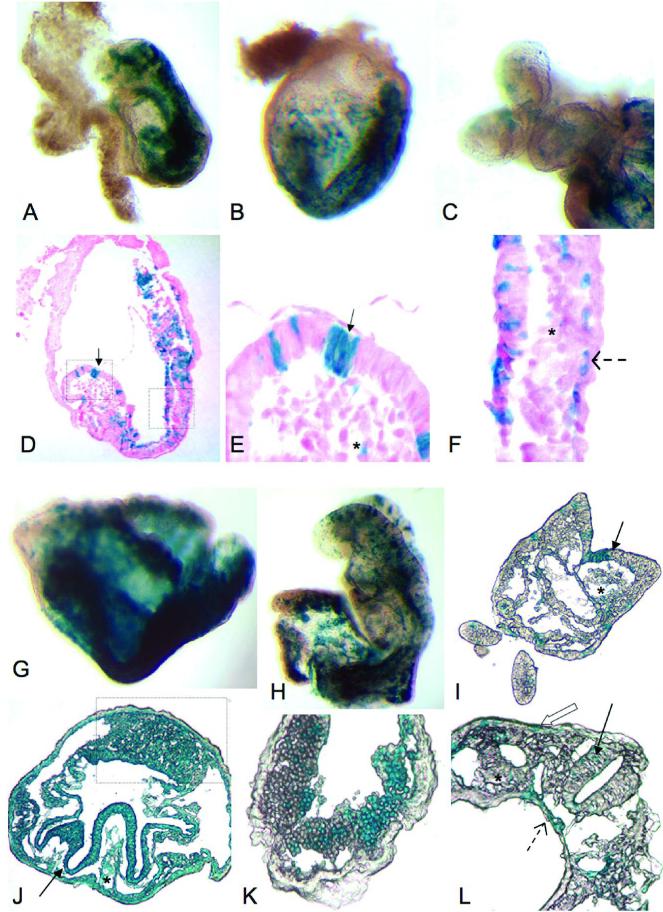

Eednull ES cells contribute to chimeras

The most stringent test of pluripotency for murine ES cells is whether the ES cells can contribute to all tissue lineages in chimeric embryos. Previously, we had published that Eednull ES cells could contribute to all lineages in embryoid bodies as well as chimeric embryos21. These experiments were completed using ES cells at an early passage number (p5). To determine whether EED and H3K27 methylation is required for the maintenance of the pluripotent state, we repeated chimera analysis using low and high pass Eednull ES cells. Low pass (p7) or high pass (p34) Eednull ES cells were injected into 3.5 dpc wild-type blastocysts. Chimeric embryos were dissected 6, 7, or 10 days after blastocyst injection (equivalent to 9.5, 10.5, or 12.5 dpc) and were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase activity. Eednull ES cells carry a β-geo cassette at the Rosa26 locus, allowing mutant cells to be tracked because of their blue color upon staining. Both low and high passage Eednull ES cells were able to contribute to all tissues in chimeric embryos. Table 1 summarizes results from blastocyst injections.

Table 1.

Summary of blastocyst injections

| Stage | Total embryos | Resorptions | Number of chimeras | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early passage (p7) Eednull ES | 9.5 dpc | 15 | 1 | 6 (43%) |

| Late passage (p34) Eednull ES | 9.5 dpc | 27 | 2 | 13 (52%) |

| Late passage (p34) Eednull ES | 10.5 dpc | 11 | 2 | 3 (33%) |

| Late passage (p34) Eednull ES | 10.5 dpc | 53 | 17 | ND |

| Late passage (p34) Eednull ES | 12.5 dpc | 7 | 0* | 3 (43%)* |

Total number of embryos from 3 females. Suggests that there may have been earlier resorptions.

High contribution chimeras were obtained with both sets of Eednull ES cells. From early pass ES cells, 4 embryos had at least 50% Eednull ES cell contribution. From late pass ES cells at 9.5 dpc, 8 embryos had at least 50% Eednull ES cell contribution. Figure 5A-C, and 5G and H, show representative high or moderate contribution chimeric embryos from low pass and high pass mutant cells, respectively. Eednull cells could be found in all tissues. Figure 5D-F, depicts histological sections from low pass chimeric embryos. Arrow, asterisk, and dashed arrow indicate ES cell contribution to neurectoderm, mesoderm, and gut endoderm tissues, respectively. Figure 5I-L, represents histological sections from high pass Eednull chimeras. Arrows, asterisks, and dashed arrows, indicate ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm derivatives, respectively. It is worth noting, as described previously21, high contribution chimeras produced with Eednull ES cells display some of the same defects as homozygous mutant embryos (Fig.5G & J). These defects include an overabundance of allantois (boxed area; Fig. 5J), a poorly developed neurectoderm (arrow; Fig. 5J), and paucity of embryonic mesoderm (asterisk, Fig. 5J). These defects are likely to cause embryonic lethality around 10.5 dpc in the highest contribution chimeras. Moderate chimeras develop normally, and Eednull cells appear morphologically normal in surface epithelia (open arrow; Fig. 5L), neurectoderm (arrow; Fig. 5I), and embryonic blood (Fig 5K). By the most stringent measures, both early and late passage Eednull ES cells are indeed pluripotent.

Figure 5. Chimeric contribution of Eednull ES cells.

Eednull cell contribution in chimeric embryos recovered at 9.5 dpc is visualized by β-galactosidase staining. Whole-mount embryos from chimeric embryos made with low pass Eednull ES cells (A-C) show fairly normal development of even moderately high contribution chimeras (A,B). Eednull cells can occasionally be seen in the embryonic forebrain and heart field (C), although these areas were reported to be relatively devoid of mutant cells in chimeric embryos21. Paraffin sections (D, with futher magnification in E and F) revealed that low pass Eednull ES cells contribute to tissues derived from all three embryonic germ layers, including neurepithelium (arrows; D, E), mesenchyme (asterisk; E,F) gut endoderm (dashed arrow; F). Results were similar to those previously reported in21. (G-L) High pass Eednull cell contribution in chimeric embryos recovered at 9.5 dpc is visualized by β-galactosidase staining. Whole-mount images representing high (G) and moderate (H) contribution chimeric embryos are shown. High contribution chimeras are almost exclusively Eednull ES cell derived, as indicated by blue staining in the whole-mount embryo (G) and cryosections (J). As reported previously21, high contribution chimeras suffer defects also seen in homozygous Eednull embryos, including an overgrown allantois (boxed area; J), poorly developed neurepithelium (arrow; J), and severe sparsity of embryonic mesoderm (asterisk; J). Moderate range chimeras show relatively normal development (G, I, and L), with Eednull cells contributing seamlessly to neurepithelium (solid arrows; I, L), surface epithelium (open arrow; L), mesenchyme (asterisk; I,L), and endoderm (dashed arrow; L). Even relatively well-differentiated cell types, such as embryonic blood (K) can be populated by Eednull cells.

Lethality of differentiated Eednull cells

Despite robust participation by Eednull cells in 9.5 dpc chimeric embryos, Eednull cells are scarce in 12.5 dpc embryos. In later stage chimeric embryos, Eednull cells appear to be limited to a few neurons (arrows, Fig. S3) and embryonic blood cells (asterisk, Fig. S3), occurring only in a few embryos. Reduced numbers of 12.5 dpc embryos were recovered from blastocyst injections, and many of those embryos were defective. We suspect that the lack of embryos and the defects observed may be due to the death of high contribution chimeric embryos and to the loss of differentiated Eednull cells that were previously contributing to moderate or low contribution chimeric embryos.

To determine whether terminally differentiated Eednull cells were capable of survival, we isolated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from 10.5 dpc chimeric embryos. We chose this stage because it preceded the wave of lethality of high to moderate contribution chimeras, but produced larger embryos with more cells. Whole 10.5 dpc embryos were dissociated by passage through a needle and plated. Eednull cells can be selected for using G418 because the mutant ES cells contain a β-geo cassette at the Rosa26 locus, which confers resistance to G418. Twenty-four hours after plating, G418 was added to some of the MEFs in culture. Although wild-type MEFs could be recovered from embryos without selection, Eednull MEFs were not recovered from dissociated embryos plated with or without G418. In some cases, poor cellular growth occurred from plated embryos, even in the absence of G418. In these cases, few cells attached to the tissue culture dish, and they failed to divide further. One similar MEF outgrowth was stained for β-galactosidase activity, and positive staining confirmed that the cells were Eednull. A few (4 total) LacZ positive cells were also seen in a robustly growing MEF culture without G418 selection, 4 days after initial plating. However, upon splitting this culture Eednull (LacZ positive) cells could not be found. These data suggest that Eednull MEFs cannot be maintained in culture.

Discussion

Previous studies demonstrated a role for PRC2 and H3K27me3 in the repression of developmental regulators15, 16, 18, 24. Boyer et al. extended this observation to suggest that PRC2 was required for maintenance of the pluripotent state because Eednull ES cells aberrantly express lineage-specific markers and spontaneously differentiate in culture16, 18. However, the same Eednull ES cells were previously shown to contribute to all tissue lineages in embryoid bodies and chimeric embryos, and are therefore functionally pluripotent21. These disparate results were obtained with high passage and low passage Eednull ES cells, respectively. We hypothesized that high passage Eednull ES cells were not pluripotent, and that differences between low and high passage ES cells would reveal the factors responsible for the loss of pluripotency.

Since previously published characterization of H3K27 methylation in Eednull ES cells was carried out on high passage cells, we first wanted to verify that low passage mutant ES cells lacked global H3K27 methylation. Previous data suggested that H3K27me1 may be mediated by a complex other than the canonical PRC2 complex and that EED is also a member of the alternate complex2, 29 (S. Chamberlain and T. Magnuson, unpublished data). To our surprise, low passage Eednull ES cells retained H3K27me1, while high passage mutant cell lines lacked this modification. H3K27me2 and me3 are found at the promoters of genes silenced by PRC2, but the function of H3K27me1 is poorly understood. H3K27me1 is thought to be a dynamic modification that is widely distributed across euchromatin, except for the transcriptional start sites of active genes30. We speculate that EED likely mediates monomethylation since it is absent in high passage mutant ES cells. However, the removal of H3K27me1 may occur passively, as opposed to H3K27me3, which can be actively removed by the histone demethylases UTX and JMJD3. Upon comparing cellular morphology and expression profiles of low passage and high passage Eednull ES cells, we found few changes, suggesting that global expression changes do not result from the loss of H3K27 monomethylation.

The changes in expression between Eednull ES cells and passage-matched wild-type ES cells that we observed agreed with previously published reports15, 18, 23 that demonstrated increased expression levels of developmental regulators in Eednull ES cells. Ectopic expression of lineage-specific genes was observed in both low and high passage Eed mutant ES cells. Expression levels of many genes became further increased in high passage mutant ES cells. These data support a role for PRC2 in the repression of developmental regulators.

Ectopic expression of developmental regulators can drive in vitro differentiation of ES cells. For instance, forced expression of Gata4 and Gata6 directs ES cell differentiation to primitive endoderm31, and overexpression of Cdx2 is sufficient to differentiate ES cells to trophectoderm32, 33. Differentiation induced by overexpression of Cdx2, Gata4 and Gata6 was reinforced by downregulation of Oct4 and Nanog. Furthermore, depletion of OCT4, NANOG, or SOX2 alone can result in the functional loss of pluripotency in embryos and ES cells25-27, 34, 35. Expression levels of Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 were reduced in Eednull ES cells, however, mutant ES cells retained expression of the pluripotency-associated transcription factors. Reduced expression levels of Oct4, Nanog and Sox2 may reflect early differentiation due to the brief feeder-free culture condition. Robust staining for OCT4 and NANOG proteins in Eednull ES cells maintained on feeders supports this possibility.

We also considered genes that were downregulated during the first 18 hours of differentiation by LIF removal28. The reduced expression of these genes most closely correlated with loss of functional pluripotency, suggesting that they were the downstream mediators of the pluripotent state. Many of these factors have promoters that are themselves bound by OCT4, NANOG, or SOX2 in mouse35 or human ES cells36, and thus are likely to represent part of the same transcriptional network. Eednull ES cells retain expression of these pluripotency markers. Additionally, low passage Eed mutant ES cells had higher expression levels than wild-type ES cells. Although transcription factors known to mediate pluripotency are reduced in Eednull ES cells, genes most closely correlated with functional pluripotency are not. This could occur because the level of transcription of pluripotency-associated transcription factors, although reduced, is sufficient to direct proper expression of downstream markers. Interestingly, recently reported induced pluripotent cell lines also show severely reduced levels of Oct4 and Sox2, but are functionally pluripotent37.

Eednull ES cells were previously shown to be pluripotent by their ability to form three germ layers and differentiate in vitro into various tissue types, including neurons, in embryoid bodies, and by incorporation into most tissues of chimeric embryos21. Furthermore, primordial germ cells are also specified in Eednull embryos, suggesting that mutant cells can even contribute to the germline11. While these experiments were performed with the earliest passages of Eednull ES cells, we have demonstrated here that both low and high passage Eednull ES cells are pluripotent by chimeric embryo analyses, the most stringent test of pluripotency for mouse ES cells.

Neurons can be generated from in vitro differentiation of Eednull ES cells21 but MEFs cannot. Consistent with this finding, high contribution Eednull chimeras have a paucity of mesoderm, but form neurectoderm. This suggests that although EED is dispensable for the maintenance of a pluripotent stem cell population, it is still required for differentiation and/or maintenance of multipotent progenitors. Interestingly, very few of the genes that are upregulated in Eednull ES cells are marked with bivalent chromatin modifications in NPCs compared to MEFs20. The bivalent modifications mark promoters that are silenced, but poised for expression in that cell type19. The overexpression of genes that are required to be repressed in MEFs may explain why we cannot derive that cell type from chimeric embryos. Conversely, few of the overexpressed genes are required to be silenced in NPCs, in agreement with the relatively normal development of neural precursor cells in embryoid bodies.

SUZ12-deficient ES cells have also been derived, and although it is not known whether they are pluripotent, they can be maintained in culture and stain positively for OCT4 and NANOG 38. In contrast to EED-deficient ES cells, SUZ12-deficient ES cells cannot form neurons after in vitro differentiation. While it is formally possible that a function for SUZ12 outside of the canonical PRC2 complex could explain the disparate results, we think that this is unlikely because SUZ12 protein is absent from EED-deficient ES cells2. One possible explanation is that the retinoic acid (RA)-induced differentiation scheme used by Pasini et al. induced PRC2-regulated genes that otherwise remained repressed in the EED-deficient embryoid bodies that were not differentiated using RA. A recent report demonstrates that RA directly induces expression of the JMJD3 histone demethylase, suggesting that RA induces activation of PRC2-regulated genes via JMJD339. A better understanding of the interplay between PRC2 and its corresponding histone demethylases during transcriptional activation is needed to fully understand this dilemma. In any case, SUZ12-and EED-deficient ES cells each maintain expression of key pluripotency factors while simultaneously expressing known differentiation factors. This creates a situation where factors both positively and negatively influencing stem cell self-renewal co-exist.

A minimal set of pluripotency factors may promote the necessary gene expression and cell proliferation that is required to support stem cell self-renewal. The forced co-expression of 4 transcription factors, Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and Myc can reprogram terminally differentiated fibroblasts into pluripotent ES-like cells that contribute to the germline37, 40, 41. OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 function as transcription factors or co-activators26, 42, 43, while MYC promotes the G1 to S phase transition44. While OCT4 may mediate gene repression by binding and activating the Eed promoter17, we have demonstrated that that gene repression mediated by EED is not necessary for the maintenance of pluripotent ES cells.

To our knowledge, no known epigenetic repressor is required for the maintenance of pluripotency. In fact, a histone lysine demethylase that reverses a repressive histone modification is essential for pluripotency45. We propose a positive-only model for the maintenance of pluripotency in ES cells (Figure 6). Expression of pluripotency factors or their downstream targets may be sufficient to sustain self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells, even when lineage-specific factors are aberrantly expressed. The notion that epigenetic repression is dispensable for embryonic stem cell self-renewal is further supported by observations that ES cells maintain an open chromatin conformation15, 46, 47 and transcribe a large number of genes48, 49 50, 51. These data support the hypothesis that pluripotency is the default state for genetic systems45, 52.

Figure 6. Positive-only model for the maintenance of stem cell pluripotency.

This cartoon demonstrates how pluripotency factors might regulate stem cell self-renewal in the absence of repressive factors. PRC2, and perhaps other repressive factors are dispensable for the maintenance of pluripotency in mouse ES cells.

Conclusions

Our findings challenge the idea that PRC2 is necessary for the maintenance of pluripotent stem cells.. We found that ES cells lacking PRC2 and H3K27 methylation are functionally pluripotent. This observation has important implications in the understanding of embryonic stem cell biology. First, although PRC2 is important in early embryo development, it is not required to maintain the pluripotent stem cell population. Secondly, maintainted pluripotency of PRC2-deficient ES cells in the presence of aberrantly expressed differentiation factors implies that repression of differentiation is also not required for the maintenance of pluripotent stem cells. Thus, the repressive activity of PRC2 on developmental regulators, while ultimately detrimental to the survival of differentiated cells, is dispensable for maintaining pluripotency in embryonic stem cells.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Eednull ES cells can be maintained with normal morphology. Phase-contrast images of low (p7, left) and high (p34, right) pass Eednull ES cells are shown. Both classes of ES cells display normal ES cell morphology when maintained on a MEF feeder layer, in contrast to data reported by Ura et al1. However, when Eednull ES cells are cultured off of the feeder layer, they develop a flatter morphology and undergo spontaneous differentiation.

Table S1: Promoters with bivalent histone modifications in ES cells are upregulated in the absence of EED

Table S2: Many overexpressed transcripts arise from bivalent promoters

Figure S2. Corresponding DAPI images for Figure 3C.

Wild-type and high pass Eednull ES cells were stained with antibodies against OCT4 and NANOG. These images represent DAPI staining to show colony boundaries.

Figure S3. Chimeric contribution of Eednull ES cells in 12.5 dpc embryos.

High pass Eednull ES cells were used to generate chimeric embryos that were allowed to develop to 12.5 dpc. Fewer embryos were recovered at this time point (Table 3), and embryos that were recovered showed lower contribution of Eednull cells in the chimeric embryo (a, b). Embryos also appeared more poorly developed, despite having fewer Eednull cells (a), suggesting that mutant cells may be lost, resulting in developmental defects.

Figure S4. Immunocytochemistry for CDX2 and OCT4 in Eednull ES cells.

Cdx2 mRNA is upregulated more than 2-fold in Eednull ES cells and its promoter is marked by a bivalent domain in ES cells. We wondered whether overexpression of Cdx2 mRNA resulted in overexpression of CDX2 protein. Wild-type (right panel) or mutant (left panel) ES cells were stained with antibodies against CDX2 and OCT4. CDX2 is marginally increased in mutant cells compared to wild-type cells, however CDX2 does not seem to preferentially stain areas of spontaneous differentiation.

Table S3 Legend:

Table of transcripts that are upregulated at least 2-fold in Eednull ES cells versus wild-type merged with chromatin modification profile data from Mikkelsen et al.2. Transcripts are upregulated in either low passage or high passage mutant ES cells. A value of 0 indicates that transcript was not represented in Mikkelsen et al. data., while a value of “None” indicates neither H3K4me3 nor H3K27me3 are found at the promoter of that transcript.

1. Ura H, Usuda M, Kinoshita K, et al. STAT3 and Oct-3/4 control histone modification through induction of Eed in embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. Jan 16 2008.

2. Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. Aug 2 2007;448(7153):553−560.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hyung-Suk Kim for quantitative RT-PCR support, Jade Zhang and the Animal Models Core for accommodating the blastocyst injections, Jessica Nadler for gene expression microarray assistance, and Andy Fedoriw for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by an NRSA Fellowship to S.J.C. and a grant from the NIH to T.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cao R, Zhang Y. SUZ12 is required for both the histone methyltransferase activity and the silencing function of the EED-EZH2 complex. Mol Cell. 2004 Jul 2;15(1):57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montgomery ND, Yee D, Chen A, et al. The murine polycomb group protein Eed is required for global histone H3 lysine-27 methylation. Curr Biol. 2005 May 24;15(10):942–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao R, Zhang Y. The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004 Apr;14(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoeftner S, Sengupta AK, Kubicek S, et al. Recruitment of PRC1 function at the initiation of X inactivation independent of PRC2 and silencing. Embo J. 2006 Jul 12;25(13):3110–3122. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xi S, Zhu H, Xu H, Schmidtmann A, Geiman TM, Muegge K. Lsh controls Hox gene silencing during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Sep 4;104(36):14366–14371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703669104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlando V. Polycomb, epigenomes, and control of cell identity. Cell. 2003 Mar 7;112(5):599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ringrose L, Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:413–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lessard J, Schumacher A, Thorsteinsdottir U, van Lohuizen M, Magnuson T, Sauvageau G. Functional antagonism of the Polycomb-Group genes eed and Bmi1 in hemopoietic cell proliferation. Genes Dev. 1999 Oct 15;13(20):2691–2703. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamminga LM, Bystrykh LV, de Boer A, et al. The Polycomb group gene Ezh2 prevents hematopoietic stem cell exhaustion. Blood. 2006 Mar 1;107(5):2170–2179. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalantry S, Mills KC, Yee D, Otte AP, Panning B, Magnuson T. The Polycomb group protein Eed protects the inactive X-chromosome from differentiation-induced reactivation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006 Jan 15; doi: 10.1038/ncb1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faust C, Schumacher A, Holdener B, Magnuson T. The eed mutation disrupts anterior mesoderm production in mice. Development. 1995 Feb;121(2):273–285. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bracken AP, Pasini D, Capra M, Prosperini E, Colli E, Helin K. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. Embo J. 2003 Oct 15;22(20):5323–5335. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widschwendter M, Fiegl H, Egle D, et al. Epigenetic stem cell signature in cancer. Nat Genet. 2007 Feb;39(2):157–158. doi: 10.1038/ng1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyer LA, Mathur D, Jaenisch R. Molecular control of pluripotency. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006 Oct;16(5):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, et al. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat Cell Biol. 2006 May;8(5):532–538. doi: 10.1038/ncb1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006 Apr 21;125(2):301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ura H, Usuda M, Kinoshita K, et al. STAT3 and Oct-3/4 control histone modification through induction of Eed in embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2008 Jan 16; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyer LA, Plath K, Zeitlinger J, et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006 May 18;441(7091):349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006 Apr 21;125(2):315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007 Aug 2;448(7153):553–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin-Kensicki EM, Faust C, LaMantia C, Magnuson T. Cell and tissue requirements for the gene eed during mouse gastrulation and organogenesis. Genesis. 2001 Dec;31(4):142–146. doi: 10.1002/gene.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumacher A, Faust C, Magnuson T. Positional cloning of a global regulator of anterior-posterior patterning in mice. Nature. 1996 Dec 19−26;384(6610):648. doi: 10.1038/384648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Hansen KH, Helin K. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 2006 May 1;20(9):1123–1136. doi: 10.1101/gad.381706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Squazzo SL, O'Geen H, Komashko VM, et al. Suz12 binds to silenced regions of the genome in a cell-type-specific manner. Genome Res. 2006 Jul;16(7):890–900. doi: 10.1101/gr.5306606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, et al. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003 May 30;113(5):631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998 Oct 30;95(3):379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avilion AA, Nicolis SK, Pevny LH, Perez L, Vivian N, Lovell-Badge R. Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 2003 Jan 1;17(1):126–140. doi: 10.1101/gad.224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmqvist L, Glover CH, Hsu L, et al. Correlation of murine embryonic stem cell gene expression profiles with functional measures of pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2005 May;23(5):663–680. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasini D, Bracken AP, Jensen MR, Lazzerini Denchi E, Helin K. Suz12 is essential for mouse development and for EZH2 histone methyltransferase activity. Embo J. 2004 Oct 13;23(20):4061–4071. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vakoc CR, Sachdeva MM, Wang H, Blobel GA. Profile of histone lysine methylation across transcribed mammalian chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Dec;26(24):9185–9195. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01529-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujikura J, Yamato E, Yonemura S, et al. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells is induced by GATA factors. Genes Dev. 2002 Apr 1;16(7):784–789. doi: 10.1101/gad.968802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niwa H, Toyooka Y, Shimosato D, et al. Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 determines trophectoderm differentiation. Cell. 2005 Dec 2;123(5):917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolkunova E, Cavaleri F, Eckardt S, et al. The caudal-related protein cdx2 promotes trophoblast differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006 Jan;24(1):139–144. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masui S, Nakatake Y, Toyooka Y, et al. Pluripotency governed by Sox2 via regulation of Oct3/4 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007 Jun;9(6):625–635. doi: 10.1038/ncb1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loh YH, Wu Q, Chew JL, et al. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2006 Apr;38(4):431–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005 Sep 23;122(6):947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006 Aug 25;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasini D, Bracken AP, Hansen JB, Capillo M, Helin K. The Polycomb Group protein Suz12 is required for Embryonic Stem Cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Mar 5; doi: 10.1128/MCB.01432-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jepsen K, Solum D, Zhou T, et al. SMRT-mediated repression of an H3K27 demethylase in progression from neural stem cell to neuron. Nature. 2007 Nov 15;450(7168):415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature06270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007 Jul 19;448(7151):313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007 Jun 6; doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan H, Corbi N, Basilico C, Dailey L. Developmental-specific activity of the FGF-4 enhancer requires the synergistic action of Sox2 and Oct-3. Genes Dev. 1995 Nov 1;9(21):2635–2645. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakatake Y, Fukui N, Iwamatsu Y, et al. Klf4 cooperates with Oct3/4 and Sox2 to activate the Lefty1 core promoter in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Oct;26(20):7772–7782. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00468-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hooker CW, Hurlin PJ. Of Myc and Mnt. J Cell Sci. 2006 Jan 15;119(Pt 2):208–216. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loh YH, Zhang W, Chen X, George J, Ng HH. Jmjd1a and Jmjd2c histone H3 Lys 9 demethylases regulate self-renewal in embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2007 Oct 15;21(20):2545–2557. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee JH, Hart SR, Skalnik DG. Histone deacetylase activity is required for embryonic stem cell differentiation. Genesis. 2004 Jan;38(1):32–38. doi: 10.1002/gene.10250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meshorer E, Yellajoshula D, George E, Scambler PJ, Brown DT, Misteli T. Hyperdynamic plasticity of chromatin proteins in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Dev Cell. 2006 Jan;10(1):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zipori D. The nature of stem cells: state rather than entity. Nat Rev Genet. 2004 Nov;5(11):873–878. doi: 10.1038/nrg1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roeder RG. Transcriptional regulation and the role of diverse coactivators in animal cells. FEBS Lett. 2005 Feb 7;579(4):909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abeyta MJ, Clark AT, Rodriguez RT, Bodnar MS, Pera RA, Firpo MT. Unique gene expression signatures of independently-derived human embryonic stem cell lines. Hum Mol Genet. 2004 Mar 15;13(6):601–608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007 Jul 13;130(1):77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niwa H. Open conformation chromatin and pluripotency. Genes Dev. 2007 Nov 1;21(21):2671–2676. doi: 10.1101/gad.1615707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Eednull ES cells can be maintained with normal morphology. Phase-contrast images of low (p7, left) and high (p34, right) pass Eednull ES cells are shown. Both classes of ES cells display normal ES cell morphology when maintained on a MEF feeder layer, in contrast to data reported by Ura et al1. However, when Eednull ES cells are cultured off of the feeder layer, they develop a flatter morphology and undergo spontaneous differentiation.

Table S1: Promoters with bivalent histone modifications in ES cells are upregulated in the absence of EED

Table S2: Many overexpressed transcripts arise from bivalent promoters

Figure S2. Corresponding DAPI images for Figure 3C.

Wild-type and high pass Eednull ES cells were stained with antibodies against OCT4 and NANOG. These images represent DAPI staining to show colony boundaries.

Figure S3. Chimeric contribution of Eednull ES cells in 12.5 dpc embryos.

High pass Eednull ES cells were used to generate chimeric embryos that were allowed to develop to 12.5 dpc. Fewer embryos were recovered at this time point (Table 3), and embryos that were recovered showed lower contribution of Eednull cells in the chimeric embryo (a, b). Embryos also appeared more poorly developed, despite having fewer Eednull cells (a), suggesting that mutant cells may be lost, resulting in developmental defects.

Figure S4. Immunocytochemistry for CDX2 and OCT4 in Eednull ES cells.

Cdx2 mRNA is upregulated more than 2-fold in Eednull ES cells and its promoter is marked by a bivalent domain in ES cells. We wondered whether overexpression of Cdx2 mRNA resulted in overexpression of CDX2 protein. Wild-type (right panel) or mutant (left panel) ES cells were stained with antibodies against CDX2 and OCT4. CDX2 is marginally increased in mutant cells compared to wild-type cells, however CDX2 does not seem to preferentially stain areas of spontaneous differentiation.

Table S3 Legend:

Table of transcripts that are upregulated at least 2-fold in Eednull ES cells versus wild-type merged with chromatin modification profile data from Mikkelsen et al.2. Transcripts are upregulated in either low passage or high passage mutant ES cells. A value of 0 indicates that transcript was not represented in Mikkelsen et al. data., while a value of “None” indicates neither H3K4me3 nor H3K27me3 are found at the promoter of that transcript.

1. Ura H, Usuda M, Kinoshita K, et al. STAT3 and Oct-3/4 control histone modification through induction of Eed in embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. Jan 16 2008.

2. Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. Aug 2 2007;448(7153):553−560.