Abstract

Objective

To estimate the safety and efficacy of treatment with 2 mg nicotine gum for smoking cessation during pregnancy.

Methods

Pregnant women who smoked daily received individualized behavioral counseling and random assignment to a 6-week treatment with 2 mg nicotine gum or placebo, followed by a 6-week taper period. Women who did not quit smoking were instructed to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked by substituting with gum. Measures of tobacco exposure were obtained throughout the study.

Results

Participants in the nicotine (N=100) and placebo (N=94) groups were comparable in age, race/ethnicity, and smoking history. Biochemically-validated smoking cessation rates were not significantly higher with nicotine replacement therapy compared with placebo (after 6 weeks of treatment: 13% vs. 9.6%, p= .45; at 32-34 weeks of gestation: 18% vs 14.9%, p= .56). Using a completer analysis, nicotine replacement therapy significantly reduced the number of cigarettes smoked per day [nicotine replacement therapy: -5.7 (SD=6.0); placebo: -3.5 (SD=5.7); p=.035], and cotinine concentration [nicotine replacement therapy: -249 ng/mL (SD=397); placebo: -112 ng/mL (SD=333); p=.04]. Birth weights were significantly greater with nicotine replacement therapy vs. placebo [3287 g (SD=566 and 2950 g (SD=653, respectively; p<.0001]. Gestational age was also greater with NRT than placebo (38.9 wk [SD=1.7] and 38.0 wk [SD=3.3], respectively; p=.014).

Conclusion

Despite not reducing smoking during pregnancy, use of nicotine gum increased birth weight and gestational age, two key parameters in predicting neonatal wellbeing.

Introduction

Tobacco smoke contains more than 3,500 chemicals, including 100 carcinogens and mutagens, carbon monoxide (CO), nicotine, and hydrogen cyanide, all of which can be very harmful to fetal development (1). Smoking doubles the risk of delivering a low birth weight (<2500 grams) or premature infant (<37 weeks gestation) and increases the risk of numerous adverse perinatal and infant outcomes (2,3). Very low birth weight infants (<1500 grams), in particular, have exponential increases in morbidity and mortality compared to infants of normal weight (4). Smoking by pregnant women has been blamed for 12% of perinatal deaths and 10% of infant deaths in the United States (3).

Approximately 12% of U.S. women smoke during pregnancy (2), and smoking is most prevalent among women who are socioeconomically disadvantaged (5). The majority of pregnant women who smoke prior to becoming pregnant continue to smoke during pregnancy (6), with behavioral interventions alone yielding quit rates that rarely exceed 18% (7).

Given these circumstances, a need exists to examine the safety and efficacy of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Nicotine replacement therapies (NRT’s) approximately double quit rates relative to placebo in studies in non-pregnant individuals (7). However, there are conflicting findings as to whether NRT is a safe and effective adjunctive treatment for smoking cessation during pregnancy (8,9).

We conducted a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of 2-mg nicotine gum in pregnant smokers. We chose this nicotine formulation because our previous work suggested that 2 mg nicotine gum reduced nicotine exposure and generally had a lesser effect on maternal and fetal hemodynamics than ad libitum smoking (10). Moreover, based on evidence from the general population showing that different NRT formulations are similar in efficacy but an intermittent form (e.g., gum) may deliver a lower dose of nicotine than a continuous form (e.g., patch) (7), the intermittent form is recommended for smoking cessation during pregnancy. The primary outcome for this study was biochemically-confirmed, 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates at two time points: following 6 weeks of gum use and at the end of pregnancy. Other major endpoints included the birth weight of the offspring and measures of smoking reduction (11).

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Connecticut Health Center (Farmington, CT) and at each of the enrollment sites: Hartford Hospital (Hartford, CT), Hospital of Central Connecticut (New Britain, CT), and Baystate Medical Center (Springfield, MA). The study was conducted under an Independent New Drug Application by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (IND # 64,648) and was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00115687). An independent Data and Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed ongoing trial data including efficacy rates and serious adverse events throughout the study. Subjects were recruited from July 30, 2003 to September 25, 2006, with the last study subject completing participation on April 17, 2007. Subjects were primarily recruited from prenatal clinics at Hartford Hospital, New Britain General Hospital, and Baystate Medical Center. Clinic personnel would identify smokers and inquire whether the patient was interested in a research study. If so, on site research personnel would meet with potential participants. We also accepted referrals from private practitioners.

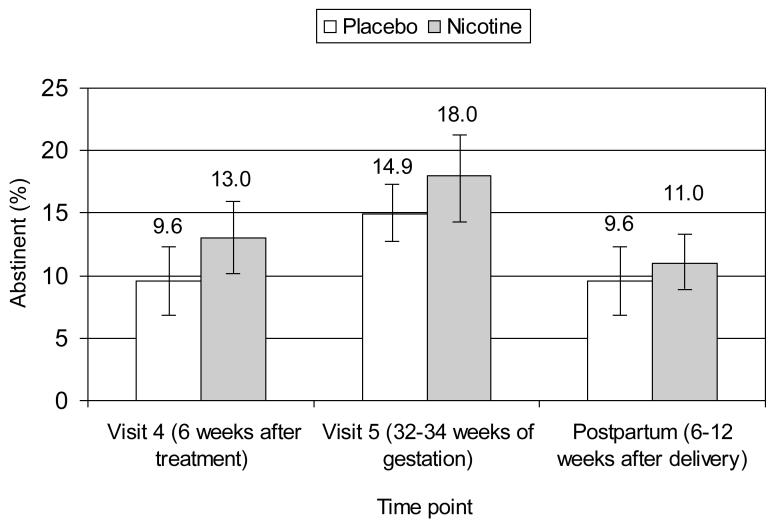

The study protocol consisted of eight visits. At the screening visit, we obtained written consent, and assessed inclusion/exclusion criteria. At the next two visits (baseline and visit 1) women received individual smoking cessation counseling by a smoking cessation therapist. At the baseline visit and every visit thereafter, the study nurse dispensed study medication, assessed smoking cessation progress, encouraged cessation, and collected information on adverse events. The timing of study visits is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study. * Significantly different follow-up rates between nicotine and placebo groups (<0.05). LTF: Lost to Follow-up and no birth outcomes obtained.

We obtained written informed consent from all participants prior to implementing any study procedures. The consent form was available in English and Spanish. We obtained parental consent and participant assent from minors enrolled at the three sites in Connecticut; however, in Massachusetts pregnant teens aged 16-18 years are emancipated, so that parental consent was not required.

Pregnant women were included if they were: a) currently smoking at least 1 cigarette per day; b) at ≤26 weeks gestation; c) ≥16 years of age; d) able to speak English or Spanish; e) intending to carry their pregnancy to term; and f) living in a stable residence. Exclusion criteria were: a) evidence of a current illicit drug or alcohol use disorder within the proceeding month (women taking methadone maintenance were included if they reported not currently using illicit drugs); b) twins or other multiple gestation; c) or an unstable psychiatric problem (e.g., suicidal ideation), an unstable medical problem (e.g., pre-eclampsia, threatened abortion) or a medical problem that would interfere with study participation (e.g., temporo-mandibular joint problems). Women with high-risk pregnancies (e.g., with diabetes or HIV) were included if they were medically stable.

A medical history and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV to assess major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (12) were administered prior to treatment. Other assessments included a smoking history, the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (13), selected questions from the Rhode Island Stress and Coping questionnaire (14), and the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) (15).

The research pharmacy used a computerized urn randomization program to balance subject assignment in the two treatment groups The balancing variables were maternal age, gestational age at study entry, number of cigarettes smoked per day, health insurance (public or private), and use of methadone maintenance (16).

Subjects received two 35-minute counseling sessions (in English or Spanish) delivered by a research assistant trained to deliver smoking cessation counseling using a motivational interviewing approach (17,18), which was previously shown to be effective when used in the same patient population (19). Research assistants (including two native Spanish speakers) received 6 hours of didactic training, reviewed videotaped smoking cessation counseling sessions, and observed two counseling sessions delivered by the trainer. In addition to the counseling sessions, subjects received printed educational materials that were tailored for use in pregnancy and twice-monthly telephone calls to monitor progress until delivery.

The counseling sessions were delivered at Baseline and Visit 1 and began with an assessment of readiness to quit smoking based (20). The initial counseling session: 1) discussed the benefits of quitting smoking during pregnancy; 2) assessed the stage of change, 3) motivated the subject to quit and 4) had the subject set a quit date within the next week. Subjects who did not commit to a quit date were instructed to reduce by half the number of cigarettes smoked per during the first week and by another half during the second week, with the goal of achieving complete cigarette abstinence by the end of the third week of treatment. The second counseling session was scheduled within one week after the quit or reduction date, and focused on strategies to deal with smoking urges and withdrawal symptoms, with the goal of smoking cessation.

The study nurse dispensed study gum [nicotine 2 mg or placebo (Fertin Pharma)] at the baseline visit and at each subsequent visit. The placebo gum had a peppery taste to mimic the taste of nicotine gum. Gum was packaged in the same ziplock foil packets to maintain the integrity of the blind. Subjects were instructed to chew one piece of gum for every cigarette they usually smoked per day, beginning on their quit date. However, subjects were instructed to not chew more than 20 pieces per day. Subjects who did not commit to a quit date were managed as above and were instructed to substitute one piece of nicotine gum daily for each cigarette that they eliminated.

Subjects received 6 weeks of treatment with the gum followed by a 6-week taper period. Subjects were encouraged to continue use of the gum as long as they were actively trying to quit smoking and were allowed to use study medication post partum to prevent smoking relapse.

At every visit, study nurses monitored patients’ smoking status (i.e., cigarettes smoked/day, exhaled CO) and adverse events. The following questionnaires were administered at every visit: Minnesota Withdrawal Symptom Checklist (20), the Rhode Island Stress and Coping Inventory (14), and the CESD (15).

The concentration of urinary cotinine, the major metabolite of nicotine and a measure of overall nicotine intake (11), was obtained prior to treatment (at both screening and baseline visits) and at visits 2, 4, and 5. Urine samples obtained at screening, baseline and visit 2 (or the next available sample) were analyzed within 1 week to identify increased nicotine exposure due to gum use. Samples were analyzed by radioimmunoassay (with a detection level of 50 ng/mL). Subjects were informed (by a research assistant not otherwise involved in patient contact) when the cotinine concentration while on treatment exceeded by 50% the higher of the screening or baseline cotinine measures and subjects were instructed to reduce their smoking and/or gum use until the cotinine concentration returned to pretreatment values.

Urine for measurement of anabasine and anatabine concentrations was obtained at baseline and visits 4 and 5. Samples were analyzed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (with a detection level of 1 ng/mL). Anabasine and anatabine are minor tobacco alkaloids that are not altered by NRT (11).

Information on adverse events (AE’s), including serious adverse events (SAE’s) was collected throughout the study. Study nurses also abstracted data on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes from the medical chart after delivery. A priori criteria for SAE’s assessed by chart review included preterm (less than 37 weeks gestation) delivery, low birth weight (<2500 grams), spontaneous abortion (unintended pregnancy loss at ≤20 weeks gestation), intrauterine fetal demise (fetal death in utero at >20 weeks gestation but prior to delivery), newborn death (age 0-28 days), maternal hospitalization for a reason other than labor and delivery, and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

We had planned to recruit 268 subjects, which would have provided power in excess of 80% (with alpha = .05, two-sided) to detect a doubling of quit rates (18% vs. 36%) and a 150-gram difference in birth weight assuming a standard deviation of 425 grams . However, after reviewing the efficacy data at the 6-week time point for 147 subjects, the DSMB recommended that enrollment be stopped due to lack of efficacy. At the time of the interim analysis, the quit rate was approximately 14% in the nicotine gum group, and 7% in the placebo group and the DSMB reasoned that a much larger sample would be needed to detect a difference of this magnitude.

Analyses were performed using SPSS, version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago Ill, 2006). Group means were compared using t-tests and frequencies were compared with the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The statistical significance for quit rates was adjusted from p<.05 to p<.018 to account for interim analyses. Non-normally distributed variables were transformed as appropriate. The test for group differences at visits 4 and 5 was based on the change scores from baseline. For group differences at visits 4 and 5, two comparisons were made, one for completers (i.e., women who provided data at these follow-up points), and one using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method.

Results

As shown in Figure 1, 250 women gave written consent for study participation and 194 women were randomly assigned to treatment (128 women recruited from Hartford Hospital, 35 women from Baystate Medical Center, and 31 from New Britain General Hospital), with 100 women allocated to receive nicotine gum and 94 women allocated to the placebo control group. The groups were comparable on all demographic, smoking history, treatment history, and pregnancy history variables (Table 1). The mean age of participants was 25.1 years (SD=5.8). The majority of the sample was Hispanic, one-half did not complete high school, only 30% were married or cohabiting, and approximately one-third were currently working.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics*

| Placebo (n=94) | Nicotine (n=100) | P-Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years | 24.7 (5.4) | 25.5 (6.8) | 0.31 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.32 | ||

| Hispanic | 52 (55%) | 53 (53%) | |

| Non Hispanic, White | 30 (32%) | 38 (38%) | |

| Non Hispanic, Black | 7 (7%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Other | 5 (5%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Education | 0.26 | ||

| Less than high school | 44 (47%) | 53 (53%) | |

| High school | 36 (39%) | 28 (28%) | |

| More than high school | 13 (14%) | 19 (19%) | |

| % Married or partnered | 28 (30%) | 30 (30%) | 0.91 |

| Insurance | 0.45 | ||

| Public | 80 (85%) | 81 (81%) | |

| Private | 14 (15%) | 19 (19%) | |

| Methadone Maintenance | 6 (7%) | 6 (6%) | 0.57 |

| Antidepressant Use | 8 (9%) | 6 (6%) | 0.51 |

| Treatment History | |||

| Mental health | 38 (41%) | 42 (42%) | 0.87 |

| Substance abuse | 19 (20%) | 17 (17%) | 0.57 |

| Smoking | |||

| # cigs/day before pregnancy | 17.8 (9.3) | 17.5 (9.6) | 0.83 |

| # cigs/day last 7 days | 8.7 (5.7) | 10.2 (6.6) | 0.10 |

| # Previous quit attempts | 2.55 (5.66) | 3.03 (5.69) | 0.34 |

| Fagerstrom score | 3.55 (1.95) | 3.83 (1.91) | 0.31 |

| Pregnancy | |||

| Number of pregnancies | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0.96 |

| Gestational age at entry (wk) | 17.1 (5.5) | 17.1 (5.6) | 0.92 |

| History preterm delivery | 16 (17%) | 13 (13%) | 0.41 |

| First pregnancy | 16 (17%) | 16 (16%) | 0.80 |

continuous variables reported as mean (standard deviation). Ordinal variables are reported as median (IQR)

χ2 for frequencies, t-test for means, Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal variables IQR, interquartile range (25thto 75thpercentile)

Participants smoked an average of 18 cigarettes/day prior to pregnancy and approximately 10 cigarettes/day during the week prior to study enrollment. The mean FTND score was <4, indicating mild-to-moderate severity of nicotine dependence (13). This was the first pregnancy for more than 15% of the women. Approximately 15% had a history of preterm delivery. Participants entered the study at a mean gestational age of 17.1 (SD=5.6) weeks.

After the baseline visit, overall, the nicotine group was more likely to attend study visits than the placebo group (71% vs. 60%; t(10)= 3.67, p=.004). The nicotine group participated at a significantly higher rate at visits 3 (χ2(1)= 5.26, p=.022) and 5 (χ2(1)= 4.74, p=.029) and at the postpartum visit (χ2(1)= 4.47, p=.035).

There were no statistically significant differences among the three sites for any of the smoking outcomes or for any of the birth outcomes. Also, there were no significant interactions between center and treatment for any of the smoking outcomes. The intraclass correlation coefficient, which measures the homogeneity of the outcome variable within clusters (centers), was small for most outcomes (<5%) suggesting that center was not an important factor for the outcomes.

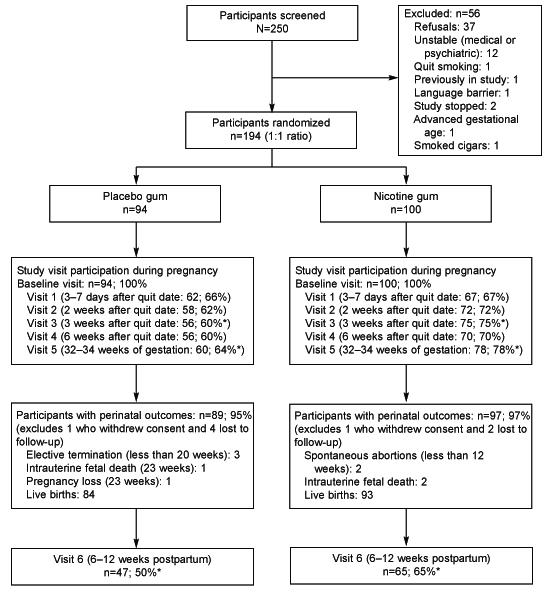

Figure 2 shows that biochemically-validated (exhaled CO value of ≤8ppm), 7 day point prevalence smoking cessation rates were non-significantly higher with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) than placebo (after 6 weeks of treatment: 13% vs. 9.6%, p= .45; at 32-34 weeks gestation: 18% vs 14.9%, p= .56). Subjects who did not attend the visit were treated as smokers.

Figure 2.

Seven-day point prevalence cigarette abstinence rates using an intent to treat analyses (N=194). Values are mean (±SE). Abstinence was confirmed by an exhaled CO of at least 8ppm.

Table 2 displays measures of tobacco exposure by treatment group for baseline and study visits 4 and 5. Across both groups there was a significant decrease from baseline to visits 4 and 5 in the number of cigarettes smoked daily (t(125) = 11.03, p<.001 and t(135) = 9.26, p<.001, respectively), exhaled CO concentration (t(123) = 4.24, p<.001 and t(134) = 5.25, p<.001, respectively), and cotinine concentration (t(114) = 3.77, p<.001 and t(124) = 5.66, p<.001, respectively). Concentrations of anatabine and anabasine did not decrease significantly at visit 4 (t(117) = 0.99, p=.33 and t(117) = 1.25, p=.21, respectively); however, both decreased significantly at visit 5 (t(124) = 2.65, p=.009 and t(124) = 2.20, p=.030, respectively).

Table 2.

Measures of Tobacco Exposure throughout the Study

| Placebo/Nicotine No. of Subjects |

Placebo Mean (SD) |

Nicotine Mean (SD) |

P-Value* | P-Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes Per Day | |||||

| Screen/Baseline | 94/100 | 8.84 (5.7) | 9.99 (6.1) | ||

| Visit 4 | 56/70 | 4.56 (5.4) | 4.59 (4.7) | 0.16 | 0.120 |

| Visit 5 | 60/76 | 5.04 (6.1) | 4.59 (4.9) | 0.077 | 0.035 |

| Cotinine (ng/mL) | |||||

| Screen/Baseline | 93/98 | 633 (559) | 672 (438) | ||

| Visit 4 | 51/64 | 577 (582) | 542 (454) | 0.10 | 0.047 |

| Visit 5 | 54/72 | 512 (531) | 492 .45(443) | 0.17 | 0.043 |

| Exhaled Carbon monoxide (ppm) | |||||

| Baseline | 94/100 | 8.69 (7.3) | 9.43 (6.3) | ||

| Visit 4 | 54/70 | 6.79 (6.6) | 7.53 (6.0) | 0.99 | 0.63 |

| Visit 5 | 57/78 | 6.36 (6.6) | 6.76 (6.2) | 0.70 | 0.53 |

| Anatabine Concentration (ng/mL) | |||||

| Baseline | 78/88 | 6.39 (10.1) | 5.67 (7.2) | ||

| Visit 4 | 40/46 | 6.38 (10.4) | 5.19 (8.3) | 0.67 | 0.32 |

| Visit 5 | 34/50 | 5.18 (8.8) | 3.71 (5.1) | 0.53 | 0.33 |

| Anabasine Concentration (ng/mL) | |||||

| Baseline | 78/90 | 4.73 (6.6) | 4.74 (5.7) | ||

| Visit 4 | 40/47 | 4.94 (7.1) | 4.18 (6.0) | 0.30 | 0.086 |

| Visit 5 | 35/51 | 4.17 (6.6) | 3.23 (4.4) | 0.31 | 0.61 |

substitution of missing data with the last available value (last observation carried forward) in analysis of change scores

analysis of change scores for participants with follow-up data (completer analyses)

The last two columns of Table 2 show the significance level for the change scores between baseline and visit 4 or visit 5 using LOCF and completer analyses. Using a completer analysis, the NRT vs, placebo group showed significantly greater reductions in cigarettes smoked per day [-5.7 cigarettes/day (SD=6.0) vs. -3.5 cigarettes/day (SD=5.7); p=.035] and in cotinine concentration [-249 ng/mL (SD=397) vs. -112 ng/mL (SD=333); p=.04]. There was also a non-significant trend in favor of the nicotine group on anabasine concentration at visit 4. Using the LOCF analysis, none of the smoking outcomes differed significantly by treatment group, with only the number of cigarettes smoked/day showing a non-significant reduction with NRT.

Birth outcomes by treatment group are shown in Table 3. There were clinically important and statistically significant differences in favor of NRT in birth weight and gestational age. There were non-significant differences favoring NRT for infant length, head circumference, and Apgar score at 5 minutes. Although Apgar scores [i.e., medians and 25th to 75th percentile interquartile range (IQR)] were the similar between groups, the full range of Apgar scores at 5 minutes was 1 to 10 for the placebo group and 5 to 10 for the nicotine group.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) Birth Outcomes*

| Placebo/Nicotine No. of subjects |

Placebo Mean (SD) |

Nicotine Mean (SD) |

P-Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Weight | ||||

| Grams | 84/93 | 2950 (653) | 3287 (566) | <0.001 |

| Gestational Age | ||||

| Weeks | 84/93 | 38.0 (3.3) | 38.9 (1.7) | 0.014 |

| Infant Length | ||||

| Cms | 80/92 | 49.0 (4.4) | 50.0 (2.7) | 0.065 |

| Head Circumference | ||||

| Cms | 72/90 | 33.5 (2.0) | 34.0 (1.7) | 0.075 |

| Apgar Score ‡ | ||||

| 1 Minute | 84/93 | 8 (1) | 8 (1) | 0.62 |

| 5 Minutes | 9 (0) | 9 (0) | 0.061 | |

| Infant Length of Stay | ||||

| Days | 81/91 | 5.46 (11.5) | 3.60 (5.6) | 0.24§ |

outcomes obtained on live born infants

t-test with nonequal variance adjustment when necessary

median value (IQR) with p value from Mann-Whitney U test

p-value from square root transformation because of excessive skewness

A non-significantly greater proportion of mother/infant pairs in the placebo group experienced at least one serious adverse event [33/87 (37.9%) vs. 24/97 (24.7%) receiving NRT] (Table 4). A striking difference, however, was the nine-fold incidence of babies with low birth weight and two-fold incidence of preterm delivery in the placebo group compared with the NRT group. Although not statistically significant, the proportion of infants with very low birth weight (<1500 grams) and neonatal intensive care unit admissions, and of newborn deaths was also lower in the nicotine group. The two infant deaths that occurred in the placebo group occurred in infants that were born prematurely and who weighed <1500 grams. The infant in the nicotine group that died was of normal birth weight and the death occurred at 2-3 weeks of age. Although the autopsy report was not available, so the cause of death is unknown, the pregnancy course was complicated by the mother’s new-onset HIV infection and the infant death was determined by an independent obstetrician to be unrelated to study treatment. The two cases of spontaneous abortion among mothers in the nicotine group occurred before 12 weeks gestation and both women had a history of previous spontaneous abortions. The incidence of other medical conditions was comparable in the treatment groups: gestational diabetes (placebo: n=6, NRT: n=7), preeclampsia (placebo: n=3, NRT: n=5), preterm premature rupture of membranes (placebo: n=4, NRT: n=6) and placental abruption (placebo: n=1, NRT: n=2). Additionally, 7 subjects in the placebo group and 9 subjects receiving NRT had evidence of other substance use at the time of delivery.

Table 4.

Frequency of Serious Adverse Events*

| Placebo (N=87) | Nicotine (N=97) | P-Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Hospitalization | 8 (9%) | 9 (9%) | 0.90 |

| Low Birth Weight | |||

| <2500 grams | 16 (18 %) | 2 (2%) | <0.001 |

| Very Low Birth Weight | |||

| < 1500 grams | 4 (5 %) | 1 (1%) | 0.19 |

| Preterm Delivery | 16 (18 %) | 7 (7.2%) | 0.027 |

| Ranges in Weeks | |||

| 22–27 | 3 (3 %) | 0 (0%) | |

| 28–31 | 1 (1 %) | 1 (1%) | |

| 32–35 | 4 (5 %) | 1 (1%) | |

| 36–37 | 8 (9 %) | 5 (5%) | |

| Spontaneous Abortion | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0.50 |

| Intrauterine Fetal Demise | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0.54 |

| Second Trimester | 1(1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.47 |

| Pregnancy Loss‡ | |||

| New Born Death | 2 (2 %) | 1 (1%) | 0.60 |

| NICU Admission | 11 (13%) | 7 (7%) | 0.20 |

| Any SAE | 33 (37.9%) | 24 (24.7%) | 0.06 |

Excludes subjects who reported elective terminations or who were lost to follow-up (i.e., did not have an SAE prior to being lost to follow-up and who had missing perinatal outcomes)

χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (when expected cell size is<5)

Pregnancy loss reported at 23 weeks; medical information not available (cause unknown) NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

Headache, dizziness, fatigue, heartburn, nausea and vomiting were the most common non-serious adverse events (moderate or greater severity reported by at least 10% of subjects) during treatment. Dizziness, heartburn, and vomiting increased significantly for both groups during treatment (McNemar change test: p<.001 for dizziness and heartburn and p=.017 for vomiting). The incidence of nausea increased more from baseline to treatment in the NRT group (20% vs. 40% ) than in the placebo group (32% vs. 34% ) (Wald χ2(1)= 4.47, p=.019).

Gum usage did not differ significantly by treatment group at any of the study visits, ranging from about 90% usage at visit 1 to 30% usage at visit 5. Similarly, neither the number of days of gum use [placebo: 29.9 (SD=3.4); NRT: 37.8 (SD=3.8)] nor the average number of pieces of gum used per day [placebo: 3.22 (SD=2.27); NRT: 3.04 (SD=2.43)] differed significantly by treatment group. There was no difference between those women who used gum and those who did not on whether they quit at visit 4 (χ2=2.16, p=.14) or visit 5 (χ2=3.18, p=.075), although there was a trend for quitters to be more likely to use gum. However, using average pieces of gum as the outcome, quitters used significantly fewer pieces of gum at visit 4 [mean (SD) = 1.72 (1.41) vs. 2.86 (2.49), t(174) = 2.09, p=.038] and visit 5 [1.61 (1.34) vs. 2.96 (2.53), t(174) = 2.94, p=.004]. A similar proportion of subjects in both groups stopped gum use due to an AE [placebo: 14/94 (15%); NRT: 12/100 (12%); χ2(1)= .35, p=0.55]. The two groups could not distinguish accurately the treatment they received, with approximately one-half of subjects in each group believing that they received NRT and approximately one-quarter believing that they received placebo gum (χ2(2)= 3.71, p=.16).

Discussion

These findings show that during pregnancy individual smoking cessation counseling with adjunctive use of 2-mg nicotine gum is associated with a modest reduction in smoking, but no increase in smoking cessation rates. NRT was, however, associated with a lower risk of preterm delivery and greater infant birth weight (i.e., yielding a weight similar to that of an infant born to a nonsmoker). There was also a trend seen for reduced infant length of stay and likelihood of NICU admission and higher Apgar scores at 5 minutes. If replicated, these findings have important implications for the management of smoking during pregnancy.

Our study population consisted primarily of socioeconomically disadvantaged women, including some who were being treated for mental health problems or who had a history of a substance use disorder (with some receiving methadone maintenance). These factors may have increased the external validity of the study, but may have also have lowered the observed efficacy rates. Nonetheless, our findings agree with those from a large 11-week comparison of nicotine with placebo patch in which non-significant differences in the rate of smoking cessation at the end of treatment (32% vs. 26%) and at the end of pregnancy (28% vs. 25%) favored the active treatment (8). Our efficacy results differ from those obtained in an open-label study of adding NRT to behavioral counseling (9). In that study, NRT improved overall quit rates. However, biochemically confirmed quit rates were low in both groups at the end of pregnancy (2% and 14%, for the placebo and nicotine groups, respectively).

In our study, the goal of the majority of women (85%) was to stop smoking, with the goal of the remainder being to reduce smoking as a precursor to cessation, an approach that has been utilized in harm reduction studies in non-pregnant smokers (22). We continued to provide gum to women as long as they were actively trying to quit. Our findings suggest that nicotine gum substitution may be effective for tobacco reduction during pregnancy. However, we cannot definitively conclude that nicotine gum reduced tobacco exposure since an effect on cigarettes smoked/per day and on biomarkers (i.e., cotinine and anabasine) was observed only in a completer analysis, not when using a more conservative LOCF approach.

Birth weight is considered to be a directly observed biomarker that is sensitive to changes in tobacco exposure during pregnancy (23). In our study, we found that birth weight was a more reliable outcome measure than other measures of tobacco exposure (as evidenced by a coefficient of variation of 17-22% for birth weight compared with 80-90% for cotinine or other measures of tobacco exposure). Additionally, follow-up data were much more complete for birth weight than for the other biomarkers (for which 30-40% of samples were missing). As a consequence, there was greater statistical power for the analysis of birth weight as an outcome measure than for cotinine or other measures of tobacco exposure, which may explain the significant effect of NRT on birth weight but less consistent effects on the other measures.

One of the major reasons to treat pregnant smokers aggressively is to improve perinatal outcomes. The better perinatal outcomes (i.e., birth weight and gestational age) with NRT in the present study may have been due to a greater reduction in smoking in that group. Another possible explanation for these findings is a beneficial effect of exogenous nicotine administration. Wisborg et al. showed that the nicotine patch was associated with a birth weight that was 150 g greater than that seen with placebo treatment, despite no evidence of a greater reduction in tobacco use (8). The authors suggested that nicotine could have an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the production of thromboxane, which may increase birth weight by reducing placental vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation. The better outcomes in the nicotine group could also have been mediated by greater treatment retention in that group, which could reflect greater compliance overall with prenatal care and could yield better birth outcomes.

Irrespective of the mechanism, the decreased risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery associated with NRT is clinically important. Two of the very low birth weight infants in the placebo group died shortly after delivery. Other low birth weight infants who survived had NICU stays of up to 3 months. These infants are at a high risk of long-term morbidity (24, 25). Moreover, the cost of treating these low birth weight infants is approximately one million dollars. With the prevalence of smoking in pregnant women being 12%, a modest reduction in the risk of low birth weight and premature delivery can, in the aggregate, be very great.

Although we examined the effect of nicotine gum on both smoking cessation and reduction, we do not recommend that nicotine gum be used routinely in prenatal care to promote smoking reduction. Cotinine monitoring was necessary to ensure that nicotine exposure was not increased above that resulting from smoking. In animal studies, nicotine causes abnormalities of cell proliferation and differentiation, leading to a reduced number of neurons and eventually to altered synaptic activity, suggesting a link to sudden infant death syndrome (26).

In summary, this study suggests that 2-mg nicotine gum does not increase smoking cessation rates, but may reduce overall tobacco exposure during pregnancy. Nicotine gum was associated with greater birth weight and gestational age than placebo gum, yielding parameters similar to those of a nonsmoker.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R01 DA15167, GCRC grant M01 RR006192, P50 DA013334, P50 AA015632. Nicotine Gum was provided free of charge from Glaxo-Smith Kline.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Oncken has received consulting fees and honoraria from Pfizer (New York, NY) for advisory board meetings. She has received at no cost nicotine and/or placebo products from Glaxo-SmithKline (Philadelphia, PA) for smoking cessation studies (i.e., for pregnant women, postmenopausal women). She has received grant funding from Pfizer for smoking cessation studies and from Nabi Biopharmaceuticals (Boca Raton, FL) for a nicotine vaccine study. Dr. Kranzler has received consulting fees from Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals (Raritan, NJ), H. Lundbeck A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark), Forest Pharmaceuticals (St. Louis, MO), elbion NV (Leuven, Belgium), Sanofi-Aventis (Bridgewater, NJ), Solvay Pharmaceuticals (Bruxelles, Belgium), and Alkermes, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). He has received research support from Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (New York, NY), and honoraria from Forest Pharmaceuticals and Alkermes, Inc. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Precis: Although nicotine gum did not increase quit rates during pregnancy, its use was associated with greater birth weight and gestational age than was placebo treatment.

References

- 1.Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I. The changing cigarette. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1997;50(4):307–364. doi: 10.1080/009841097160393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ventura SJ, Brady E, Hamilton BE, Mathews TJ, Chandra A. Trends and variations in smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight: Evidence from Birth Certificate, 1990-2000. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1176–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoyert DL, Mathews TJ, Menacker F, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics:2004. Pediatrics. 2006;117:168–183. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiClemente CC, Dolan-Mullen P, Windsor RA. The process of pregnancy smoking cessation: implications for interventions. Tobacco Control. 2000;9(Suppl III):16–21. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:541–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, Md.: 2000. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wisborg K, Henriksen TB, Jespersen LB, Secher NJ. Nicotine patches for pregnant smokers: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:967–71. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollak KI, Oncken CA, Lipkus IM, Lyna P, Swamy GK, Pletsch PK, et al. Nicotine replacement and behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in pregnancy. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oncken CA, Hatsukami DK, Lupo VR, Lando HA, Gibeau LM, Hansen RJ. Effects of short-term nicotine gum use in pregnant smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;59:654–661. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob P, Hatsukami D, Severson H, Hall S, Yu L, Benowitz NL. Anabasine and anatabine as biomarkers for tobacco use during nicotine replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2002;11:1668–1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Biometrics Research. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSMIV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition with Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fava JL, Ruggerio L, Grimley DM. The Development and Structural Confirmation of the Rhode Island Stress and Coping Inventory. J Behav Med. 1998;21(6):601–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1018752813896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;(Supplement No 12):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollnick S, Butler CC, Stott N. Helping smokers make decisions: the enhancement of brief intervention for general medical practice. Patient Education and Counseling. 1997;31:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)01004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rollnick S, Heather N, Bell A. Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: The development of brief motivational interviewing. Journal of Mental Health. 1992;1992(1):25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dornelas EA, Magnavita J, Beazoglou T, Fischer EH, Oncken C, Lando H. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a clinic-based counseling intervention tested in an ethnically diverse sample of pregnant smokers. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model. J Clin & Consult Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Picken RW, Svikis D. Tobacco withdrawal symptoms: an experimental analyses. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:231–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00427451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD005231. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005231.pub2. Review.

- 23.Hatsukami DK, Benowitz NL, Rennard SI, Oncken C, Hecht SS. Biomarkers to assess the utility of potential reduced exposure tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:169–191. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C. Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1235–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomura Y, Brooks-Gunn J, Davey C, Ham J, Fifer WP. The role of perinatal problems in risk of co-morbid psychiatric and medical disorders in adulthood. Psychol Med. 2007;10:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slotkin TA. Fetal nicotine or cocaine exposure: Which one is worse? Pharmacol Exper Ther. 1998;285:931–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]