Abstract

Crucial roles of the placenta are disrupted in early and mid-trimester pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. The pathophysiology of these disorders includes a relative hypoxia of the placenta, ischemia/reperfusion injury, an inflammatory response and oxidative stress. Reactive oxygen species including nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide and superoxide have been shown to participate in trophoblast invasion, regulation of placental vascular reactivity and other events. Superoxide, which regulates expression of redox sensitive genes, has been implicated in up-regulation of transcription factors, antioxidant production, angiogenesis, proliferation and matrix remodeling. When superoxide and nitric oxide are present in abundance, their interaction yields peroxynitrite a potent pro-oxidant, but also alters levels of nitric oxide, which in turn affect physiological functions. The peroxynitrite anion is extremely unstable thus evidence of its formation in vivo has been indirect via the occurrence of nitrated moieties including nitrated lipids and nitrotyrosine residues in proteins. Formation of 3-nitrotyrosine (protein nitration) is a “molecular fingerprint” of peroxynitrite formation. Protein nitration has been widely reported in a number of pathological states associated with inflammation but is reported to occur in normal physiology and is thought of as a prevalent, functionally relevant post-translational modification of proteins. Nitration of proteins can give either no effect, a gain or a loss of function. Nitration of a range of placental proteins is found in normal pregnancy but increased in pathologic pregnancies. Evidence is presented for nitration of placental signal transduction enzymes and transporters. The targets and extent of nitration of enzymes, receptors, transporters and structural proteins may markedly influence placental cellular function in both physiologic and pathologic settings.

Introduction

In human pregnancy, the placenta plays a crucial role between the mother and fetus, anchoring the conceptus, providing an interface for exchange of nutrients, hormone and gases as well as functioning as an immune barrier protecting the fetus. To anchor the conceptus and establish a linkage to the maternal blood supply the invading trophoblasts disrupt the extracellular matrix components of the decidua and develop dilated capacitance vessels within the uteroplacental circulation. Abnormalities in this invasive process have been correlated with early and mid-trimester pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Common threads that run through the pathophysiology of these disorders include a relative hypoxia of the placenta, ischemia/reperfusion injury, an inflammatory response and oxidative stress. The nitric oxide (NO) system has important roles in mammalian reproductive physiology, especially in the utero-placental system. NO has been shown to participate in extravillous trophoblast invasion of decidua and myometrium, in regulation of vascular reactivity of utero-placental and fetal-placental circulations, in prevention of platelet and neutrophil aggregation and adhesion in the intervillous space and in trophoblast apoptosis. In addition other reactive oxygen species including carbon monoxide and superoxide appear to have roles in the placenta. In particular superoxide which regulates expression of redox sensitive genes has been implicated in signaling events leading to up-regulation of transcription factors, antioxidant production, angiogenesis, proliferation and matrix remodeling. In an environment (placenta) where superoxide and nitric oxide are present in abundance, the interaction of the two is inevitable to yield peroxynitrite, a potent pro-oxidant. Formation of peroxynitrite will alter levels of nitric oxide, which in turn will affect physiological functions. The peroxynitrite anion is extremely unstable with a half-life of 100 ms, due to which it is undetectable and evidence of its formation in vivo has been indirect via the occurrence of nitrated moieties including nitrated lipids, nitrated nucleotides and nitrotyrosine residues in proteins [1]. Formation of 3-nitrotyrosine in proteins (protein nitration) has come to be considered a “molecular fingerprint” of peroxynitrite formation [2]. Protein nitration has been widely reported in a number of pathological states associated with inflammation but is increasingly recognized to occur in normal physiology and is now thought of as a prevalent, functionally relevant post-translational modification of proteins [1]. Nitration of proteins can give either no effect, a gain or a loss of function. Thus the occurrence, the targets and extent of nitration may markedly influence cellular function in both physiologic and pathologic settings. This review will focus on our current knowledge of protein nitration and in particular its potential roles in the placenta.

Formation of Nitric Oxide, Superoxide and Peroxynitrite

Nitric Oxide

In the late 1980s, the endothelial-derived relaxing factor was identified as nitric oxide (NO). In the vasculature, the enzymatic sources and biological effects of NO have now been well characterized. NO is released in small amounts to regulate local blood flow and inhibit interactions between circulating platelets, white cells and the vessel wall [3]. A characteristic of NO is that it is scavenged by the superoxide anion thus reducing NO activity whereas conversely the half life and effect of NO is prolonged by the presence of superoxide dismutase (SOD) which inactivates superoxide. The balance between superoxide and nitric oxide is then important in determining the physiological effects of NO. In healthy vessels NO is synthesized from the essential amino acid L-arginine and molecular oxygen [4] by a calcium/calmodulin dependent endothelial NO synthase (eNOS, type III NOS) [5]. During inflammatory episodes, a cytokine inducible, calcium independent NO synthase, (iNOS, type II NOS) is expressed throughout the vessel wall which results in production of larger quantities of NO [5]. NO is also produced in the mitochondria by mitochondrial NOS (mtNOS), a variant of neuronal NOS, which is also a calcium/calmodulin dependent isoform [6]. We characterized [7] and immunohistochemically mapped distribution of the type III eNOS isoform to vascular endothelial cells and syncytiotrophoblast cells of placental villous tissue [8]. We found increased intensity of staining for eNOS in stem villous vessels of pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia in comparison with normotensive controls [9] which correlates with increased concentrations of nitrate, a breakdown product of nitric oxide, measured in fetal blood from preeclamptic pregnancies [10, 11]. We also found expression of the type II iNOS isoform in the hofbauer cell, the specialized fetal macrophage of the human placenta [12] and also found iNOS expression in vascular endothelium and syncytiotrophoblast of some but not all normal and pathologic pregnancies. This we attribute to possible variations in inflammatory response in these placentae that stimulates iNOS expression.

Superoxide

Superoxide is formed enzymatically by the univalent reduction of oxygen as well as by non enzymatic mechanisms [1]. Enzymes that generate superoxide include NAD(P)H oxidases (NOX), the major source of superoxide in many cell types, xanthine oxidase (XO) and NOS [13]. All these enzymatic sources of superoxide have been described in the placenta [14]. Among the NOX superfamily of genes we identified the NOX-1 and and NOX-5 isoforms in syncytiotrophoblast and vascular endothelium [15] and NOX-2 in the hofbauer cell of the placenta. Molecular oxygen can also react with semiubiquinone of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and produce superoxide [13]. Up to 2% of molecular oxygen is reduced to superoxide in mitochondria [16]. Superoxide anion is generally detoxified in cellular systems by the action of enzymes such as SOD, catalase and glutathione peroxidase but also by nonenzymatic antioxidants such as glutathione, ascorbate and alpha-tocopherol [13]. Oxidative stress resulting from overproduction of superoxide is emerging as a hallmark of hypertension, cardiovascular disease and preeclampsia, a pregnancy specific disorder originating in the placenta [13]. As described above superoxide is an effective trapping agent for NO, which however results in the formation of the more powerful oxidant peroxynitrite. Mitochondria can be considered a prime site for peroxynitrite formation due to the presence of NO produced by mtNOS and superoxide resulting from leaks in the mitochondrial electron transport chain.

Peroxynitrite

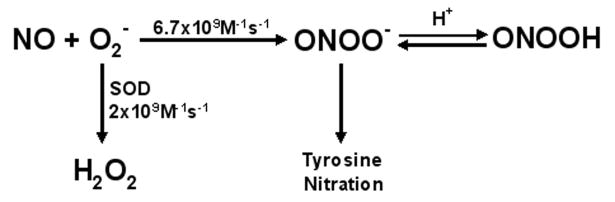

Peroxynitrite anion is formed mainly from the fast diffusion controlled reaction between nitric oxide and superoxide, where nitric oxide outcompetes SOD for superoxide [1]. Key regulators of peroxynitrite formation are therefore amounts of NO and superoxide (Figure 1). As peroxynitrite is a strong oxidant, it is rapidly consumed in target molecule reactions and has a half life less than 100 ms which allows it to travel distances of 5-20 μm (1-2 cell diameters) across extra and intracellular compartments.[1]. Peroxynitrite promotes biological effects via different types of reactions, which include direct redox reactions with thiols and metal centers, reaction with carbon dioxide, homolytic cleavage of peroxynitrous acid and incorporation of a nitro group in protein tyrosine [1]. Although NO is a highly diffusible free radical, able to diffuse 100 μm in its half life (0.5sec), superoxide is much shorter-lived and has restricted diffusion (0.4μm) in its half life. The formation of peroxynitrite is controlled by its diffusibility and half life of superoxide

Figure 1. Rate Constants for the Interaction of Nitric Oxide and Superoxide and Breakdown of Superoxide by SOD.

The rate constant for peroxynitrite formation is greater than that of dismutation of superoxide thus NO outcompetes SOD for superoxide to favor peroxynitrite formation.

Peroxynitrite production can be indirectly localized by the presence of nitrotyrosine residues [17]. Nitrotyrosine residues have been demonstrated in human atherosclerotic plaques [17], in lung sections of patients and animals with acute lung injury [18] in neurodegenerative disease and, as we have found, in the placenta in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia and pregestational diabetes [19]. Our demonstration of nitrotyrosine, in the vascular endothelium, surrounding smooth muscle and in the syncytiotrophoblast of the placenta supports local formation and action in the placenta [19]. The close proximity of eNOS [9] and NOX [15] in placental vascular endothelium and syncytiotrophoblasts also would facilitate the formation of peroxynitrite. The ability of peroxynitrite to cross cell membranes implies that peroxynitrite generated from a cellular source could influence surrounding target cells within one to two cell diameters.

Effects of peroxynitrite on biomolecules

Peroxynitrite formation in the placenta, particularly in the fetal-placental vasculature, depletes NO, an important regulator of vascular resistance in the human fetoplacental vasculature. Many biomolecules are oxidized and/or nitrated by peroxynitrite or peroxynitrite derived radicals. These include tyrosine residues, thiols, DNA and lipids. In proteins, peroxynitrite can cause tyrosine nitration, oxidation of cysteine (nitrosylation), histidine, methionine and tryptophan, and also form low levels of o-tyrosine, 3’3-dityrosine and protein carbonyls [20]. Peroxynitrite can cause both nitrosylation and nitration of lipids; these have been implicated in atherosclerotic plaques [21]. In addition peroxynitrite can also cause DNA strand breaks and oxidation and nitration of DNA bases such as guanine [21]. These modified bases can lead to DNA breaks and activate polyADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) [21] and more recently nitration of cGMP and its role in redox signaling in macrophages has been demonstrated [22]. Nitrotyrosine can also be formed by ONOO- independent pathways.. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) a heme protein expressed by leukocytes can form nitrotyrosine in the presence of nitrite [21].

Functional Consequences of Protein Nitration

Protein Activity

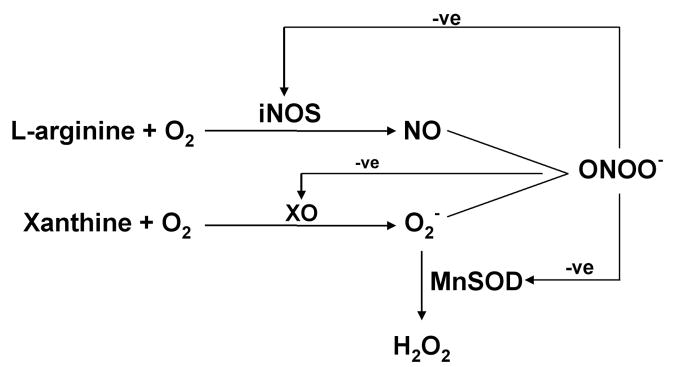

Protein nitration has been widely reported in a number of pathological states associated with inflammation, which leads to increased NO and superoxide generation, but is increasingly recognized to occur in apparently normal physiologic conditions [23] in numerous tissues and cells including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, neurons, vascular smooth muscle cells [24-26] and the placenta [19]. Nitration is now thought of as a prevalent, functionally relevant post-translational modification of proteins [1]. Many nitrated proteins have been identified including myofibrillar creatine kinase [27], prostacyclin (PGI2) synthase [28], heart succinyl-Co-A:3-oxoacid CoA transferase, [29] structural proteins such as myosin heavy chain, α-actinin and desmin [30] , insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) [31], the NMDA receptor [32] and mitochondrial enzymes involved in the citric acid cycle (malate dehydrogenase) and fatty acid β oxidation (acetyl CoA acyltransferase, enoyl-CoA hydratase and electron transfer flavoprotein) [33]. Increased protein tyrosine nitration is seen in numerous vascular and neurologic diseases [34], thus it may be considered a disease marker, indeed it is suggested to be the best indicator of cardiovascular disease [35]. Low levels of protein nitration may be a physiologic regulatory mechanism in redox regulation of signaling pathways by changing tyrosine into a negatively charged hydrophilic nitrotyrosine moiety and changing the function of a protein. A gain of function e.g. cyclooxygenase [36], poly-ADP ribose polymerase PARP [37], fibrinogen [38], protein kinase C epsilon [39] as well as no effect on function (chymotrypsin, transferrin) [38] were reported for peroxynitrite mediated effects. More commonly however inhibition of function is found e.g. MnSOD, p53, iNOS, PGI2 synthase [23, 34, 40-43] due to peroxynitrite action. Tyrosine nitration may also function as a feedback inhibitory mechanism as ONOO- inhibits inducible NOS activity [44] and XO activity and thereby O2- production [45]. Conversely as ONOO- inhibits SOD activity it may exacerbate oxidative stress [46] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Inhibitory Effects of Peroxynitrite on iNOS, Xanthine Oxidase and MnSOD.

By feedback inhibtion of the activity of iNOS, XO and MnSOD, peroxynitrite can either inhibit (iNOS or XO) or promote (MnSOD) its own formation

Protein Degradation

Tyrosine nitration may also change the rate of proteolytic degradation of a protein [47] . A number of soluble proteins treated with either peroxynitrite, or a generator of nitric oxide and superoxide are degraded by the 20 S proteasome faster than untreated proteins [48], although specific nitration and/or other modifications of these proteins were not demonstrated. Human red blood cell lysates also have been shown to degrade nitrated BSA at a rate 30% faster than non-nitrated protein [49]. There appears to be a consensus that nitrated proteins are degraded at a faster rate than non-nitrated proteins both in vivo (mammalian tissues [50], in cell culture models [47]) and in vitro studies [47], although the proteasomes (20S and 26S) as well as the ubiquitin conjugating enzymes are sensitive to inactivation by oxidants such as peroxynitrite [51-53].

Signal transduction

The concept of protein nitration functioning as a post-translational modification akin to phosphorylation is attractive and has been studied. Proteomics (2D gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry) has been used to identify nitrated proteins [54] and the effect on activity investigated. Peroxynitrite appears to act as both a positive and negative regulator of cellular signaling events. Early studies indicated peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration to inhibit phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase [55], PECAM-1, and the T cell receptor/CD3 complex [1]. Later studies have shown that nitration promoted tyrosine phosphorylation in a variety of cell types including red blood cells, bovine brain synaptosome, SH-SY5Y cells, pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells and endothelial cells [1]. Members of the MAPK family, Erk, p38 MAPK and JNK have been shown to be activated by peroxynitrite in a number of cell models [1]. A direct nitration of Erk in response to Ang II treatment of vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells has been demonstrated, but the nitrated residues have not been identified [56]. There are also reports of possible peroxynitrite mediated nitration down-regulating phosphorylation of Erk and p38 MAPK [57]. Our own data provides evidence of nitration of p38 MAPK in the placenta in association with decreased phosphorylation and activity of the enzyme [58]. Inhibition of p38 MAPK catalytic activity was more pronounced upon in vitro nitration of recombinant p38 MAPK [59]. Observations in human erythrocytes [60], where bolus additions of low concentrations of peroxynitrite induced band 3 tyrosine phosphorylation, and higher concentrations induced band 3 nitration, inhibiting phosphorylation suggest a concentration dependent activation/inhibition of phosphorylation by peroxynitrite.

Regulation of phosphotyrosine formation depends on the balance between phosphotyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) and phosphotyrosine kinases (PTKs). Peroxynitrite at low doses can inactivate PTPs by oxidation of a critical cysteine residue [61]. Receptor tyrosine kinases, particularly EGFR and PDGFR have been shown to be activated by peroxynitrite [1], although data obtained with EGFR is quite varied depending on the cell type studied with increase [62], no change [63] or a decrease in phosphorylation of EGFR [64] being observed. Similarly, Akt has been shown to be both activated [62] and inactivated by peroxynitrite [1]. The nonreceptor tyrosine kinase (NRTK) family member, src kinase has been shown to be a preferential target for peroxynitrite in a number of cell culture models [1]. This kinase has an unique activation mechanism via either a peroxynitrite induced dephosphorylation [65-67] or oxidation of cysteine [68]. The two diverse activation mechanisms have been observed in the src family members, lyn kinase [69] and hck kinase [70]. The equivalent of phosphatase activity that dephosphorylates a protein would be a denitrase. A putative denitrase activity has been demonstrated [49, 71, 72] however the protein responsible has not to date been isolated. There is however evidence for nitration/denitration being a dynamic process as illustrated by the reversible protein nitration seen in platelets [73] and the rapid oxygen regulated nitration/denitration of mitochondrial proteins [74]

Immunogenicity of Nitrated Proteins

Proteins carrying nitrotyrosine epitopes can elicit both humoral and cellular immune responses in mice. Involvement of nitrated proteins in autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematous [75], rheumatoid arthritis [76] and glomerular nephritis [77] has been recently reported. This is an emerging field which when applied to the area of reproductive biology might explain altered immune responses observed in preeclampsia.

Regulation and Specificity of Nitration

Due to its reactivity peroxynitrite anion could potentially nitrate all proteins in its path. Yet, in spite of the fact that peroxynitrite is a more powerful oxidant than its two parent molecules, NO and O2-, its reaction with electron rich groups is curiously slow, based on the rate constant.. It has been suggested that its limited reactivity with most molecules makes it unusually selective as an oxidant [1]. Peroxynitrite reacts more rapidly with CO2, (4.6× 104 M-1s-1) than its reaction with most other molecules [78] and therefore.CO2 concentrations in a cell would control tyrosine nitration.

Other factors regulating nitration include the proximity of the proteins to the nitrating agent [79]. Protein nitration may be residue-, protein- and tissue-specific, with not all tyrosine residues of a protein being nitrated and not all proteins nitrated [34, 80], depending on cellular location of the protein and the peroxynitrite generating system, the concentration of peroxynitrite produced and interaction with other molecules. The abundance of the protein and its tyrosine content have been proposed to influence protein nitration [80] as exemplified by the nitration of structural and cytoskeletal proteins such as tubulin [81], actin [82], actinin [30], myosin heavy chain [30], desmin [30] and tau [83] The frequency of tyrosine occurrence in proteins is 3-4 mol% [34] with proteins without tyrosine, such as the human Cu-Zn SOD, not being targets for nitration [34] . Interestingly, bovine Cu-Zn SOD has been shown to be nitrated on its unique tyrosine residue [84]. Other factors that influence nitration are location of the tyrosine residue (surface/packed within), neighbouring amino acids (particularly glutamic acid) [85], and presence of active site metals e.g. MnSOD [86], cytochrome C [87] or prostacyclin synthase [88] and heme proteins [89]. Tyrosine nitration may also be favored in a hydrophobic environment due to the fact that peroxynitrous acid can readily pass through lipid membranes [85, 90]. Although initially an absolute requirement of a consensus sequence for protein nitration could not be established [34], more recent work with mitochondrial protein nitration suggests the presence of a consensus sequence, [LMVI]-X-[DE]-[LMVI]-X-[FVLI]-X-Y (X is any amino acid and Y is the target tyrosine) in 10 of the 36 proteins found to be nitrated in the mitochondria [91]. However, despite the selectivity, a large number of proteins have been found to be nitrated in vivo.

Protein Nitration in Vascular Disease

Evidence from animal models and human studies implicates nitrative stress in the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) a fact underscored by the strong association between nitrotyrosine and coronary artery disease after correction for classical CV risk factors [35]. This is of particular importance in view of the fact that pregnancy per se has been described as a cardiovascular stress test [92-94]. Moreover, accumulating evidence indicates preexisting CVD to be a predisposing factor for preeclampsia as well as showing that women who develop preeclampsia are at risk for CVD in later life [93, 95]. Tyrosine nitrated proteins have been detected in several components of the cardiovascular system, ranging from plasma (fibrinogen, plasmin, Apo-1), vessel wall (Apo-B, cyclooxygenase, prostacyclin synthase, MnSOD) to myocardium (myofibrillar creatine kinase, alpha-actinin, sarcoplasmic Ca2+ ATPase) [40].

Peroxynitrite and Protein Nitration in Placenta: Occurrence and Functional Effects

The occurrence of nitrated proteins in vivo was first deduced from the observation of nitrotyrosine and its deaminated, decarboxylated metabolite 3-nitro-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid in the urine of humans with sepsis [79]. We first demonstrated increased nitrotyrosine staining in the vascular endothelium and surrounding vascular smooth muscle of placenta from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia [58] and pregestational diabetes. We subsequently demonstrated that in vitro peroxynitrite treatment of the placental vasculature from normal placenta altered vascular reactivity [96] such that the vascular responses resembled those seen from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia or pregestational diabetes, implying a functional effect. Increased nitrotyrosine residues have also been found in the maternal vasculature in preeclampsia [97].but whether this is pregnancy specific or preexists and identifies women with preexisting vascular disease (chronic hypertension, diabetes, and previous history of preeclampsia) who are at risk for developing preeclampsia in pregnancy is unknown [98]. If increased nitrative stress is considered to be an etiologic factor in preeclampsia, then it could possibly be due to preexisting nitrative stress resulting from a maternal vasculature previously compromised by cardiac disease or metabolic syndrome.

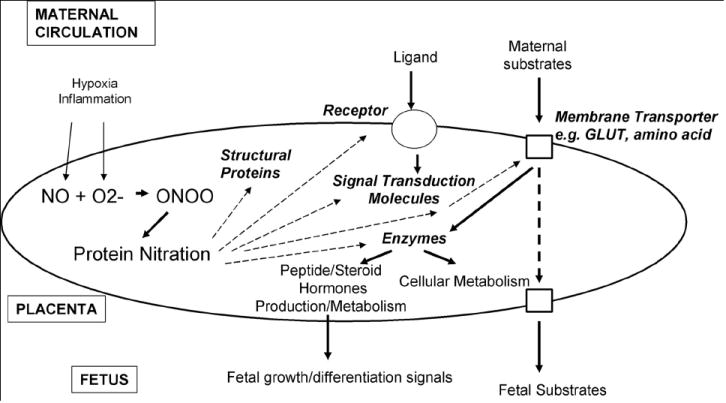

Potential targets for nitration with critical functions in the placenta could include membrane receptors, transporters, channels, signal transduction molecules, enzymes, structural proteins etc (Figure 3). We have shown p38 MAPK, a critical signaling molecule to be increasingly nitrated in the placenta in preeclampsia which results in loss of catalytic activity for the kinase [58] . We have also shown that p38 MAPK can be nitrated in vitro by authentic peroxynitrite with resultant loss of catalytic activity. LC-MS analysis identified 3 residues Y132, Y245 and Y258 to be nitrated in p38 MAPK [59]. Targeted inactivation of the p38 MAPKα is accompanied by early embryonic lethality in mice and is associated with defects in placental development due to loss of labyrinth and reduced spongiotrophoblast layers in the placenta, reduced vascularization of labyrinth and increased apoptosis [99]. Nitration of p38 MAPK and p53 (unpublished) in the placenta therefore could potentially affect growth, hypertrophy or apoptosis. Hypoxia-reoxygenation (a condition that favors oxidative and nitrative stress) in villous explants has been shown to cause activation of the p38 MAPK pathway [100]. It also regulates nitration/denitration of mitochondrial proteins [74]. Interestingly, a very recent report on hypoxia induced reactive species in ovine fetal pulmonary veins demonstrate nitration of protein kinase G with resultant decrease in PKG activity [101].

Figure 3. Targets for Protein Nitration in the Placenta.

Tyrosine nitration of key regulatory molecules in the placenta may potentially alter placental function

Immunoprecipitation with antinitrotyrosine antibodies reveals many nitrated proteins in the normal placenta again reinforcing the concept that nitration is a physiologically relevant covalent modification. Among these we have found p53, the tumor suppressor protein and Poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) to be nitrated. Previous reports have shown that nitration inactivates and activates these proteins respectively. We postulate that oxidative and nitrative stress may be mechanisms that alter placental function. We have shown increased nitration of the purinergic receptor P2X4 in the preeclamptic placenta [102]. Nitration of these ligand-gated ion channels may alter endothelium dependent vasodilation or smooth muscle contraction based on known functions of the purinergic receptor. We have also recently observed nitration of the taurine transporter (unpublished) in the placenta and find an increased proportion of nitration of the taurine transporter with preeclampsia plus IUGR compared to normotensive controls suggesting nitration may regulate amino acid transport across the placenta. and play a role in etiologies such as IUGR where hypoxia and resultant oxidative stress are seen.

Nitration of Vascular Proteins In the Placenta

Nitric Oxide Synthase

As previously stated NO has a major role during normal pregnancy being involved in maternal vasodilation, regulation of fetal-placental vascular reactivity, trophoblast invasion and apoptosis and platelet adhesion and aggregation in the intervillous space. Proinflammatory conditions such as occur in pregnancy complicated by IUGR, preeclampsia or diabetes, may see a 1000 fold increase in the respective amounts of superoxide and NO. This would result in a 1,000,000 fold increase in peroxynitrite production, as the rate of formation of the product, peroxynitrite is equivalent to the product of the concentration of the reactants, NO and superoxide [1]. The inducible NOS isoform has been found to be nitrated in murine lung epithelial cells treated with peroxynitrite with resultant decreased NO production [44] illustrating an inhibitory feedback mechanism. Decreased activity of recombinant iNOS when nitrated has been reported [103] and in vivo iNOS has been shown to be nitrated in skeletal muscle of patients with sepsis [103]. Potentially NOS may be nitrated in the placenta resulting in feedback inhibition. Such decreased activity of NOS may have a role in the vasoconstriction observed in preeclampsia.

Cylooxygenase and prostacyclin synthase

Eicosanoids are important in the normal homeostasis of endothelium and have a heightened role in pregnancy [104]. Production of thromboxane by COX-1 in platelets is required for platelet aggregation, thrombus formation and vasoconstriction [105]. Interestingly, COX-1 has been shown to be activated, resulting in increased thormboxane production, by low concentrations of peroxynitrite in human platelets Peroxynitrite interaction with COX-1 is however complex and has been shown to either activate [106] or inactivate [107] it depending on the nature of its interaction. Peroxynitrite as a peroxidase substrate can activate COX, but by tyrosine nitration also inhibit it. Increased thromboxane biosynthesis correlates with severity of preeclampsia and might be attributable to the actions of peroxynitrite [108].

PGI2 synthase, located on the endothelium produces PGI2 from PG endoperoxide that is formed by the action of COX. The capacity of blood vessels to generate PGI2 is essential to the integrity of the endothelium and this is possibly regulated due to the molecular cross talk between NO and prostaglandin pathways. NO and prostaglandin pathways are induced by the same cytokines [109, 110] and it is likely they are negatively regulated by peroxynitrite. Peroxynitrite has been shown to readily nitrate and inactivate PGI2 synthase in human aortic endothelial cells, bovine coronary artery segments and also in a mouse model of diabetes [88]. Interestingly PGI2 synthesis is reduced in preeclampsia [111] which may well be due to decreased activity of PGI2 synthase as a result of its nitration. Inactivation of PGI2 synthase would lead to accumulation of PG endoperoxide, which in turn would lead to activation of thromboxane receptors that would trigger vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation and apoptosis [112], all of which are hallmarks of preeclampsia. Peroxynitrite has a dual regulatory role on PGI2 synthase. At concentrations below 50 nM, it is almost essential for PGI2 activity, providing the “peroxide tone”, possibly stimulating the formation of PG endoperoxide, whereas at concentrations above 50 nM, it can inactivate and inhibit PGI2 synthase by tyrosine nitration [113].

The artery wall is a major source of nitrative protein modifications in several pathologies such as hypertension, atheromatosis and preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is associated with an exacerbation of inflammatory responses [114]. Complex metabolic changes resulting from the inflammatory process occur in the inflammatory microenvironment of the vessel wall. Cytokine activated endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells would produce superoxide in the vessel well [115-118]. Activated macrophages and neutrophils would release large amounts of superoxide, nitric oxide and MPO at the site of injury [115, 116]. Therefore, the vessel wall provides the optimal milieu for nitration reactions to occur. Nitration of LDL triggered release of TNF-alpha can further exacerbate oxidative and nitrative stress in the vessel wall [13]. It is possible that nitration of PGI synthase, NOS and COX-1 in the vasculature contributes to the endothelial dysfunction that is characteristic of preeclampsia. Increased nitrotyrosine residues have been demonstrated in the omental vessels from individuals with preeclampsia [97].

Peroxynitrite and Mitochondria

The considerable metabolic activity of the placenta and generation of reactive oxygen species means that normal pregnancy is a state of oxidative stress which is heightened in preeclampsia where there are further increases in production of reactive oxygen species and in consumption of antioxidant defenses, particularly in the placenta. Defective mitochondria generate more reactive oxygen species, primarily superoxide at complexes I and III by auto-oxidation and electron leaks. The mitochondria have been highlighted as the source of this increased oxidative stress in preeclampsia by Wang and Walsh [119] who found that not only were superoxide, oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation increased in the preeclamptic placenta but this was associated with an increase in the amount of mitochondria, in mitochondrial enzyme activity and in susceptibility of mitochondria to oxidation. Mitochondria may also play a role in apoptosis in the trophoblast as release of cytochrome c from the respiratory chain, has been shown to trigger apoptosis [120]. Increased cytosolic calcium is apoptogenic and linked to increased mitochondrial calcium uptake [121] and increased NOS activity. However this effect can be prevented by MnSOD [122], or by peroxynitrite scavengers [123], thus indicating the involvement of superoxide and peroxynitrite.

Peroxynitrite has been shown to exert significant inhibition on most components of the electron transport chain including complex I, III and V through cysteine oxidation, tyrosine nitration and damage of iron sulfur centers [124]. A list of mitochondrial proteins reported to be altered, their mechanism of alteration and model studied in is given in a review by Elfering et al [91] . One of the earliest proteins found to be nitrated in vivo (renal allografts) was the mitochondrial MnSOD [125]. Since then it has been detected in a number of human neurological disorders [126, 127], vascular aging [128] and in mice [129, 130]. This would prevent the breakdown of superoxide and its accumulation which further augments peroxynitrite formation. Peroxynitrite has been shown to alter proteins in all four compartments of mitochondria either by oxidation or nitration [91]. At low fluxes, peroxynitrite can be decomposed by reactions with cytochrome c oxidase, glutathione, ubiquinol and possibly NADH with limited damage. However at moderate to high doses, oxidation/nitration of critical mitochondrial proteins can trigger mitochondrial signaling of cell death due to alterations in calcium homeostasis and permeation transition pore opening [124]. Thus mitochondrial dysfunction caused by peroxynitrite can contribute both to altered energy metabolism and increased apoptosis, as seen in the syncytiotrophoblast in preeclampsia [131] and perhaps interfering with trophoblast invasion, which may lead then to the cascade of events that result in preeclampsia.

Oxidized and nitrated proteins are targeted for faster proteolytic degradation [47]. Exposure of mitochondria to NO at micromolar concentrations for long periods inhibits respiration and complex I activity while not affecting complex II and III [132]. This tyrosine nitration of complex I was prevented by SOD and uric acid thus being attributable to peroxynitrite. The nitrated tyrosine residues in complex I have been described [133]. Further during ischemia, NO and calcium, as described earlier, cause loss of mitochondrial cytochrome c and initiate caspase 3-dependent apoptosis [134].

Inflammation, Oxidative and Nitrative Stress

Pre-pregnancy obesity increases the risk of poor pregnancy outcome. In a retrospective cohort study Ray et al [135] found that women with features of the metabolic syndrome before pregnancy including obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia had a higher risk of placental dysfunction and fetal demise. Inflammatory disease increases the risk of poor pregnancy outcome. Maternal asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus and periodontal disease are all associated with reduced fetal growth (reviewed in Murphy et al [136]) suggesting that active inflammation during pregnancy may contribute to reduced fetal growth. Indeed elevated serum or placental inflammatory cytokines are associated with IUGR [137]. High altitude pregnancy is also associated with increased TNFα and IL-6 which may provide a link to altered growth [138].

Cytokines, the mediators of the inflammatory response, are secreted by cells of the immune system, by adipocytes and also by the placenta. In diabetes and obesity synthesis of cytokines is increased [139, 140]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-6 negatively regulate glucose and lipid metabolism and inhibit insulin action in insulin sensitive tissues [141]. Placental cytokines may induce fetal insulin resistance [142]. The placenta and adipose tissue both express adipose tissue related proteins (adipokines) and inflammatory genes, and their expression is increased in diabetic pregnancy [143]. This suggests the placenta can have a major role in control of glucose metabolism and insulin action and that it may function to link inflammatory mediators to metabolism. For example TNFα induces insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) phosphorylation therefore linking insulin action to inflammation. Recently peroxynitrite has been shown to impair insulin-stimulated glucose uptake by 3T3-L1 adipocytes [31] suggesting excessive inflammation and oxidative stress leading to nitrative stress could then have a deleterious effect. This was associated with repression of IRS-1-associated PI3-kinase activity. Mass spectrometric analysis revealed that peroxynitrite caused nitration of 4 tyrosine residues on IRS-1 including Tyr939 the docking site for a PI3-kinase subunit [31]. Nitration of the glucocorticoid receptor has recently been shown to enhance ligand binding and enhance anti-inflammatory effects [144]. Nitration may therefore regulate activity of key proteins in inflammatory responses, along with glucocorticoid and insulin action in the placenta.

We have recently found that protein nitration was increased in the placenta of obese individuals (BMI>30) compared to lean controls (BMI<25) (unpublished). This was accompanied by a relative decrease in the amount of protein carbonyls, a specific measure of protein oxidation caused predominantly by superoxide, with increasing obesity. We attribute this finding to increased nitric oxide, produced under the influence of inflammatory cytokines, scavenging superoxide and thus concomitantly reducing the potential for formation of protein carbonyls. Supporting evidence for this possibility comes from a similar finding of increased nitration in the placenta at high altitude coupled with a decrease in oxidative stress by Zamudio et al [145]. However, in several other situations, such as colon of patients with irritiable bowel syndrome [146], alzheimer’s disease, diabetes [147], morbidly obese individuals [148] and also in the placenta and decidua of women with preeclampsia and concurrent HELLP syndrome [149], higher levels of protein carbonyls have been found along with increased protein nitration. As protein nitration at tyrosine residues may have different functional effects than protein oxidation via carbonyl formation at lysine, arginine, proline and threonine residues [150] , this may alter placental function in a differential manner.

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress

Emerging data indicates that peroxynitrite can mediate endoplasmic reticulum stress with resultant activation of ER stress markers Gp96 and Grp78 in atherosclerosis [151-153] and in a number of cell culture models [153-156]. We (unpublished) and others [157] have shown that peroxynitrite can induce activation of ER stress components in trophoblasts. We have further demonstrated the upregulation of Gp96 in a proteomic screen in the preeclamptic placenta [158]. Interestingly in the placenta Gp96 demonstrates endothelial localization, where increased nitrotyrosine immunostaining has been previously observed.

Measurement of Nitrotyrosine and Disease Diagnosis

In vivo accurate determination of nitrotyrosine represents an experimental challenge. Several methods, including antibody based (dot blots and ELISA), gas chromatography, HPLC and mass spectrometry based methods have been used [159]. The current trend is to estimate nitrotyrosine in conjunction with tyrosine using stable isotope dilution with mass spectrometry [160, 161]. Pharmacological strategies including therapy with antioxidants, peroxynitrite scavengers, decomposition catalysts and inhibitors of superoxide formation (e.g. statins) have been shown to decrease vascular protein nitration and revert organ/tissue dysfunction in models of sepsis, heart senescence, angiotensin II-induced cerebral flow dysfunction and post ischemic heart apoptosis [162]. In a case controlled study, a strong association between systemic levels of protein-bound nitrotyrosine and coronary artery disease risk was found [162]. These investigators were also able to show in an interventional study that statin (superoxide formation inhibitors) therapy reduced nitrotyrosine levels significantly. Another useful approach to diagnosis is to estimate the urinary metabolite of 3-nitrotyrosine, 3-nitro-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (NHPA). Urinary elimination of NHPA has been suggested to be useful as biomarkers for overall nitrotyrosine formation [163] in vivo. A recent study that looked at the level of NHPA in the urine of neonates to find an association with preterm birth [164] did not however find any difference.

Conclusions

Although there is abundant evidence both from our studies and those of others demonstrating protein nitration as a pathological phenomenon based on its occurrence in many disease states, the occurrence of nitration in normal physiology, its involvement in signal transduction and the dynamic regulation of nitration suggests it is a physiologic and functionally relevant covalent modification. The isolation of a denitrase linked to reversibility of nitration would solidify the concept of nitration being akin to phosphorylation as a signaling mechanism. As an organ that exhibits oxidative and nitrative stress even in the “physiologic state” and heightened oxidative and nitrative stress in the pathologic state, the placenta may be particularly prone to the effects of peroxynitrite which significantly alters protein function, oxidizes lipids, alters critical mitochondrial functions and inflicts damage to nucleic acids. We find an increase in nitrotyrosine and nitrated proteins in the placenta in preeclampsia, with pregestational diabetes and with obesity as compared to normal pregnancies. The common linkage here may be the inflammatory milieu, well known to stimulate peroxynitrite formation. At the molecular, cellular and tissue level an important challenge is to demonstrate a direct relationship between protein nitration and functional changes in the placenta. A useful tool for the study of the effect of nitration on protein function may be the recently reported in vitro technique for the incorporation of nitrotyrosine into proteins at genetically encoded sites using amino acetyl tRNA synthase in a site specific manner [165]. Performing this modification in selected proteins may allow demonstration of distinct functional alterations as a result of nitration and broaden our knowledge of this modification as a regulator of protein function. Measurement of systemic levels of nitrotyrosine might provide an important diagnostic tool in pathologic pregnancies. Although purely speculative at this stage, a useful translation of this basic knowledge of nitration would be to identify and stratify women at risk for preeclampsia on the basis of nitrotyrosine levels in their serum/urine. This might target a population for possible interventional therapies to reduce nitrative stress. As the function of membrane receptors, transporters, enzymes, structural proteins and signal transduction molecules may all be affected by nitration, oxidative and nitrative stress may be subtle yet powerful modulators of many aspects of placental function and thus assume critical roles in fetal growth and development in both normal and abnormal pregnancy and also in fetal programming.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH grant HL075297

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimersthat apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric Oxide and Peroxynitrite in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radi R. Nitric oxide, oxidants, and protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4003–4008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannon RO., 3rd Role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular disease: focus on the endothelium. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1809–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koppenol WH. The basic chemistry of nitrogen monoxide and peroxynitrite. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raij L. Nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of cardiac disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2006;8:30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2006.06025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghafourifar P, Sen CK. Mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1072–1078. doi: 10.2741/2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myatt L, Brockman DE, Langdon G, Pollock JS. Constitutive calcium-dependent isoform of nitric oxide synthase in the human placental villous vascular tree. Placenta. 1993;14:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(05)80459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myatt L, Brockman DE, Eis AL, Pollock JS. Immunohistochemical localization of nitric oxide synthase in the human placenta. Placenta. 1993;14:487–495. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(05)80202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myatt L, Eis AL, Brockman DE, Greer IA, Lyall F. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in placental villous tissue from normal, pre-eclamptic and intrauterine growth restricted pregnancies. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:167–172. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyall F, Greer IA, Young A, Myatt L. Nitric oxide concentrations are increased in the feto-placental circulation in intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 1996;17:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(96)80009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyall F, Young A, Greer IA. Nitric oxide concentrations are increased in the fetoplacental circulation in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:714–718. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myatt L, Eis AL, Brockman DE, Kossenjans W, Greer I, Lyall F. Inducible (type II) nitric oxide synthase in human placental villous tissue of normotensive, pre-eclamptic and intrauterine growth-restricted pregnancies. Placenta. 1997;18:261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)80060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madamanchi NR, Vendrov A, Runge MS. Oxidative Stress and Vascular Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:29–38. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150649.39934.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myatt L, Cui X. Oxidative stress in the placenta. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:369–382. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui X-L, Brockman D, Campos B, Myatt L. Expression of NADPH oxidase isoform 1 (Nox1) in human placenta: Involvement in preeclampsia. Placenta. 2006;27:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carreras MC, Poderoso JJ. Mitochondrial nitric oxide in the signaling of cell integrated responses. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1569–1580. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00248.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beckman J, Ye Y, Anderson P, Chen J, Accqvitti M, Trapey M, White C. Extensive nitration of protein tyrosines in human atherosclerosis detected by immunohistochemistry. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1994;375:81–88. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1994.375.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haddad IY, Pataki G, Hu P, Galliani C, Beckman JS, Matalon S. Quantitation of nitrotyrosine levels in lung sections of patients and animals with acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2407–2413. doi: 10.1172/JCI117607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myatt L, Rosenfield RB, Eis AL, Brockman DE, Greer I, Lyall F. Nitrotyrosine residues in placenta. Evidence of peroxynitrite formation and action. Hypertension. 1996;28:488–493. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radi R, Peluffo G, Alvarez MN, Naviliat M, Cayota A. Unraveling peroxynitrite formation in biological systems. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:463–488. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen YR, Chen CL, Chen W, Zweier JL, Augusto O, Radi R, Mason RP. Formation of protein tyrosine ortho-semiquinone radical and nitrotyrosine from cytochrome c-derived tyrosyl radical. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feelisch M. Nitrated cyclic GMP as a new cellular signal. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:687–688. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1107-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenacre SA, Ischiropoulos H. Tyrosine nitration: localisation, quantification, consequences for protein function and signal transduction. Free Radic Res. 2001;34:541–581. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidge ST, Ojimba J, McLaughlin MK. Vascular function in the vitamin E-deprived rat: an interaction between nitric oxide and superoxide anions. Hypertension. 1998;31:830–835. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.3.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frustaci A, Kajstura J, Chimenti C, Jakoniuk I, Leri A, Maseri A, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Myocardial cell death in human diabetes. Circ Res. 2000;87:1123–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kajstura J, Fiordaliso F, Andreoli AM, Li B, Chimenti S, Medow MS, Limana F, Nadal-Ginard B, Leri A, Anversa P. IGF-1 overexpression inhibits the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2001;50:1414–1424. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mihm MJ, Coyle CM, Schanbacher BL, Weinstein DM, Bauer JA. Peroxynitrite induced nitration and inactivation of myofibrillar creatine kinase in experimental heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:798–807. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou MH, Leist M, Ullrich V. Selective nitration of prostacyclin synthase and defective vasorelaxation in atherosclerotic bovine coronary arteries. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1359–1365. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65390-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turko IV, Marcondes S, Murad F. Diabetes-associated nitration of tyrosine and inactivation of succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid CoA-transferase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2289–2294. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mihm MJ, Yu F, Carnes CA, Reiser PJ, McCarthy PM, Van Wagoner DR, Bauer JA. Impaired myofibrillar energetics and oxidative injury during human atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104:174–180. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nomiyama T, Igarashi Y, Taka H, Mineki R, Uchida T, Ogihara T, Choi JB, Uchino H, Tanaka Y, Maegawa H, Kashiwagi A, Murayama K, Kawamori R, Watada H. Reduction of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake by peroxynitrite is concurrent with tyrosine nitration of insulin receptor substrate-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zanelli SA, Ashraf QM, Mishra OP. Nitration is a mechanism of regulation of the NMDA receptor function during hypoxia. Neuroscience. 2002;112:869–877. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koeck T, Stuehr DJ, Aulak KS. Mitochondria and regulated tyrosine nitration. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1399–1403. doi: 10.1042/BST0331399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ischiropoulos H. Biological tyrosine nitration: a pathophysiological function of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;356:1–11. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Brennan ML, Fu X, Goormastic M, Pearce GL, Gokce N, Keaney JF, Jr, Penn MS, Sprecher DL, Vita JA, Hazen SL. Association of nitrotyrosine levels with cardiovascular disease and modulation by statin therapy. Jama. 2003;289:1675–1680. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landino LM, Crews BC, Timmons MD, Morrow JD, Marnett LJ. Peroxynitrite, the coupling product of nitric oxide and superoxide, activates prostaglandin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:15069–15074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szabo C, Zingarelli B, O’Connor M, Salzman AL. DNA strand breakage, activation of poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase, and cellular energy depletion are involved in the cytotoxicity of macrophages and smooth muscle cells exposed to peroxynitrite. Proc Natl Acad of Sci. 1996;93:1753–1758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gole MD, Souza JM, Choi I, Hertkorn C, Malcolm S, Foust RF, III, Finkel B, Lanken PN, Ischiropoulos H. Plasma proteins modified by tyrosine nitration in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L961–967. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.5.L961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balafanova Z, Bolli R, Zhang J, Zheng Y, Pass JM, Bhatnagar A, Tang X-L, Wang O, Cardwell E, Ping P. Nitric Oxide (NO) Induces Nitration of Protein Kinase Cepsilon (PKCepsilon), Facilitating PKCepsilon Translocation via Enhanced PKCepsilon -RACK2 Interactions. A novel mechanism of NO-triggered activation of PKC epsilon. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15021–15027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peluffo G, Radi R. Biochemistry of protein tyrosine nitration in cardiovascular pathology. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cobbs CS, Samanta M, Harkins LE, Gillespie GY, Merrick BA, MacMillan-Crow LA. Evidence for peroxynitrite-mediated modifications to p53 in human gliomas: possible functional consequences. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;394:167–172. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chazotte-Aubert L, Hainaut P, Ohshima H. Nitric oxide nitrates tyrosine residues of tumor-suppressor p53 protein in MCF-7 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:609–613. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacMillan-Crow LA, Thompson JA. Tyrosine modifications and inactivation of active site manganese superoxide dismutase mutant (Y34F) by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;366:82–88. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson VK, Sato E, Nelson DK, Camhi SL, Robbins RA, Hoyt JC. Peroxynitrite inhibits inducible (type 2) nitric oxide synthase in murine lung epithelial cells in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:986–991. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee CI, Liu X, Zweier JL. Regulation of xanthine oxidase by nitric oxide and peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9369–9376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Thompson JA. Peroxynitrite-mediated inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase involves nitration and oxidation of critical tyrosine residues. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1613–1622. doi: 10.1021/bi971894b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Souza JM, Choi I, Chen Q, Weisse M, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, Obin M, Ara J, Horwitz J, Ischiropoulos H. Proteolytic degradation of tyrosine nitrated proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;380:360–366. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grune T, Blasig IE, Sitte N, Roloff B, Haseloff R, Davies KJA. Peroxynitrite Increases the Degradation of Aconitase and Other Cellular Proteins by Proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10857–10862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gow AJ, Duran D, Malcolm S, Ischiropoulos H. Effects of peroxynitrite-induced protein modifications on tyrosine phosphorylation and degradation. FEBS Letters. 1996;385:63–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grune T, Reinheckel T, Davies K. Degradation of oxidized proteins in mammalian cells. FASEB J. 1997;11:526–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinheckel T, Sitte N, Ullrich O, Kuckelkorn U, Davies KJA, Grune T. Comparative resistance of the 20 S and 26 S proteasome to oxidative stress. Biochemical Journal. 1998;335:637–642. doi: 10.1042/bj3350637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jahngen-Hodge J, Obin MS, Gong X, Shang F, Nowell TR, Jr, Gong J, Abasi H, Blumberg J, Taylor A. Regulation of Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzymes by Glutathione Following Oxidative Stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28218–28226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glockzin S, von Knethen A, Scheffner M, Brune B. Activation of the Cell Death Program by Nitric Oxide Involves Inhibition of the Proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19581–19586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aulak KS, Miyagi M, Yan L, West KA, Massillon D, Crabb JW, Stuehr DJ. Proteomic method identifies proteins nitrated in vivo during inflammatory challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12056–12061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221269198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saeki M, Maeda S. p130cas is a cellular target protein for tyrosine nitration induced by peroxynitrite. Neurosci Res. 1999;33:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pinzar E, Wang T, Garrido MR, Xu W, Levy P, Bottari SP. Angiotensin II induces tyrosine nitration and activation of ERK1/2 in vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5100–5104. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiroycheva M, Ahmed F, Anthony GM, Szabo C, Southan GJ, Bank N. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in kidneys of beta(s) sickle cell mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1026–1032. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1161026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Webster RP, Brockman D, Myatt L. Nitration of p38 MAPK in the placenta: association of nitration with reduced catalytic activity of p38 MAPK in pre-eclampsia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006 doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Webster RP, Macha S, Brockman D, Myatt L. Peroxynitrite treatment in vitro disables catalytic activity of recombinant p38 MAPK. Proteomics. 2006;6:4838–4844. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mallozzi C, Di Stasi AM, Minetti M. Peroxynitrite modulates tyrosine-dependent signal transduction pathway of human erythrocyte band 3. Faseb J. 1997;11:1281–1290. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.14.9409547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takakura K, Beckman JS, MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP. Rapid and irreversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases PTP1B, CD45, and LAR by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;369:197–207. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klotz LO, Schieke SM, Sies H, Holbrook NJ. Peroxynitrite activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway in human skin primary fibroblasts. Biochem J. 2000;352(Pt 1):219–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van der Vliet A, Hristova M, Cross CE, Eiserich JP, Goldkorn T. Peroxynitrite induces covalent dimerization of epidermal growth factor receptors in A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31860–31866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uc A, Kooy NW, Conklin JL, Bishop WP. Peroxynitrite inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in Caco-2 cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2353–2359. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000007874.20403.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roskoski R., Jr Src kinase regulation by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lowell CA. Src-family kinases: rheostats of immune cell signaling. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:631–643. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pu M, Akhand AA, Kato M, Hamaguchi M, Koike T, Iwata H, Sabe H, Suzuki H, Nakashima I. Evidence of a novel redox-linked activation mechanism for the Src kinase which is independent of tyrosine 527-mediated regulation. Oncogene. 1996;13:2615–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mallozzi C, Di Stasi MA, Minetti M. Peroxynitrite-dependent activation of src tyrosine kinases lyn and hck in erythrocytes is under mechanistically different pathways of redox control. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:1108–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mallozzi C, Di Stasi AM, Minetti M. Nitrotyrosine mimics phosphotyrosine binding to the SH2 domain of the src family tyrosine kinase lyn. FEBS Lett. 2001;503:189–195. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuo WN, Kanadia RN, Shanbhag VP, Toro R. Denitration of peroxynitrite-treated proteins by ‘protein nitratases’ from rat brain and heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;201:11–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1007024126947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuo WN, Kocis JM, Webb JK. Protein denitration/modification by Escherichia coli nitrate reductase and mammalian cytochrome P-450 reductase. Front Biosci. 2002;7:9–14. doi: 10.2741/A734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Low SY, Sabetkar M, Bruckdorfer KR, Naseem KM. The role of protein nitration in the inhibition of platelet activation by peroxynitrite. FEBS Lett. 2002;511:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koeck T, Fu X, Hazen SL, Crabb JW, Stuehr DJ, Aulak KS. Rapid and selective oxygen-regulated protein tyrosine denitration and nitration in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27257–27262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khan F, Ali R. Antibodies against nitric oxide damaged poly L-tyrosine and 3-nitrotyrosine levels in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;39:189–196. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2006.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khan F, Siddiqui AA. Prevalence of anti-3-nitrotyrosine antibodies in the joint synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;370:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hsu HC, Zhou T, Kim H, Barnes S, Yang P, Wu Q, Zhou J, Freeman BA, Luo M, Mountz JD. Production of a novel class of polyreactive pathogenic autoantibodies in BXD2 mice causes glomerulonephritis and arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:343–355. doi: 10.1002/art.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Augusto O, Bonini MG, Amanso AM, Linares E, Santos CC, De Menezes SL. Nitrogen dioxide and carbonate radical anion: two emerging radicals in biology. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:841–859. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Freeman BA. NO-dependent protein nitration: a cell signaling event or an oxidative inflammatory response? Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Souza JM, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, Raman CS, Ischiropoulos H. Factors determining the selectivity of protein tyrosine nitration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;371:169–178. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Landino LM, Iwig JS, Kennett KL, Moynihan KL. Repair of peroxynitrite damage to tubulin by the thioredoxin reductase system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Neumann P, Gertzberg N, Vaughan E, Weisbrot J, Woodburn R, Lambert W, Johnson A. Peroxynitrite mediates TNF-alpha-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction and nitration of actin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L674–L684. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00391.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reynolds MR, Reyes JF, Fu Y, Bigio EH, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Berry RW, Binder LI. Tau nitration occurs at tyrosine 29 in the fibrillar lesions of Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10636–10645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2143-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oneda H, Inouye K. Effect of Nitration on the Activity of Bovine Erythrocyte Cu,Zn-Superoxide Dismutase (BESOD) and a Kinetic Analysis of Its Dimerization-Dissociation Reaction as Examined by Subunit Exchange between the Native and Nitrated BESODs. J Biochem. 2003;134:683–690. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bartesaghi S, Ferrer-Sueta G, Peluffo G, Valez V, Zhang H, Kalyanaraman B, Radi R. Protein tyrosine nitration in hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments. Amino Acids. 2007;32:501–515. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Quijano C, Hernandez-Saavedra D, Castro L, McCord JM, Freeman BA, Radi R. Reaction of peroxynitrite with Mn-superoxide dismutase. Role of the metal center in decomposition kinetics and nitration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11631–11638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cassina AM, Hodara R, Souza JM, Thomson L, Castro L, Ischiropoulos H, Freeman BA, Radi R. Cytochrome c nitration by peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21409–21415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909978199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zou MH. Peroxynitrite and protein tyrosine nitration of prostacyclin synthase. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;82:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mehl M, Daiber A, Herold S, Shoun H, Ullrich V. Peroxynitrite reaction with heme proteins. Nitric Oxide. 1999;3:142–152. doi: 10.1006/niox.1999.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bartesaghi S, Valez V, Trujillo M, Peluffo G, Romero N, Zhang H, Kalyanaraman B, Radi R. Mechanistic studies of peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration in membranes using the hydrophobic probe N-t-BOC-L-tyrosine tert-butyl ester. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6813–6825. doi: 10.1021/bi060363x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elfering SL, Haynes VL, Traaseth NJ, Ettl A, Giulivi C. Aspects, mechanism, and biological relevance of mitochondrial protein nitration sustained by mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H22–29. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00766.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Khalil RA, Crews JK, Novak J, Kassab S, Granger JP. Enhanced Vascular Reactivity During Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Synthesis in Pregnant Rats. Hypertension. 1998;31:1065–1069. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.5.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barden A. Pre-eclampsia: contribution of maternal constitutional factors and the consequences for cardiovascular health. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:826–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Williams D. Pregnancy: a stress test for life. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:465–471. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Newstead J, von Dadelszen P, Magee LA. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular risk. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2007;5:283–294. doi: 10.1586/14779072.5.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kossenjans W, Eis A, Sahay R, Brockman D, Myatt L. Role of peroxynitrite in altered fetal-placental vascular reactivity in diabetes or preeclampsia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1311–1319. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Roggensack AM, Zhang Y, Davidge ST. Evidence for Peroxynitrite Formation in the Vasculature of Women With Preeclampsia. Hypertension. 1999;33:83–89. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ray J. Metabolic syndrome and higher risk of maternal placental syndromes and cardiovascular disease. Drug Development Research. 2006;67:607–611. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adams RH, Porras A, Alonso G, Jones M, Vintersten K, Panelli S, Valladares A, Perez L, Klein R, Nebreda AR. Essential role of p38alpha MAP kinase in placental but not embryonic cardiovascular development. Mol Cell. 2000;6:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cindrova-Davies T, Spasic-Boskovic O, Jauniaux E, Charnock-Jones DS, Burton GJ. Nuclear Factor-{kappa}B, p38, and Stress-Activated Protein Kinase Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling Pathways Regulate Proinflammatory Cytokines and Apoptosis in Human Placental Explants in Response to Oxidative Stress: Effects of Antioxidant Vitamins. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1511–1520. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Negash S, Gao Y, Zhou W, Liu J, Chinta S, Raj JU. Regulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated vasodilation by hypoxia-induced reactive species in ovine fetal pulmonary veins. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1012–1020. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00061.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roberts VH, Webster RP, Brockman DE, Pitzer BA, Myatt L. Post-Translational Modifications of the P2X(4) purinergic receptor subtype in the human placenta are altered in preeclampsia. Placenta. 2007;28:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lanone S, Manivet P, Callebert J, Launay JM, Payen D, Aubier M, Boczkowski J, Mebazaa A. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) expressed in septic patients is nitrated on selected tyrosine residues: implications for enzymic activity. Biochem J. 2002;366:399–404. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carbillon L, Uzan M, Uzan S. Pregnancy, vascular tone, and maternal hemodynamics: a crucial adaptation. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000;55:574–581. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200009000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moncada S, Vane JR. Pharmacology and endogenous roles of prostaglandin endoperoxides, thromboxane A2, and prostacyclin. Pharmacol Rev. 1978;30:293–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Boulos C, Jiang H, Balazy M. Diffusion of Peroxynitrite into the Human Platelet Inhibits Cyclooxygenase via Nitration of Tyrosine Residues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zou M, Martin C, Ullrich V. Tyrosine nitration as a mechanism of selective inactivation of prostacyclin synthase by peroxynitrite. Biol Chem. 1997;378:707–713. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.7.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang YP, Walsh SW, Kay HH. Placental Lipid Peroxides and Thromboxane Are Increased and Prostacyclin Is Decreased in Women with Preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;167:946–949. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Salvemini D. Regulation of cyclooxygenase enzymes by nitric oxide. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1997;53:576–582. doi: 10.1007/s000180050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Clancy R, Varenika B, Huang W, Ballou L, Attur M, Amin AR, Abramson SB. Nitric oxide synthase/COX cross-talk: nitric oxide activates COX-1 but inhibits COX-2- derived prostaglandin production. J Immunol. 2000;165:1582–1587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Remuzzi G, Marchesi D, Zoja C, Muratore D, Mecca G, Misiani R, Rossi E, Barbato M, Capetta P, Donati MB, de Gaetano G. Reduced umbilical and placental vascular prostacyclin in severe pre-eclampsia. Prostaglandins. 1980;20:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(80)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bachschmid M, Thurau S, Zou MH, Ullrich V. Endothelial cell activation by endotoxin involves superoxide/NO-mediated nitration of prostacyclin synthase and thromboxane receptor stimulation. Faseb J. 2003;17:914–916. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0530fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Klumpp G, Schildknecht S, Nastainczyk W, Ullrich V, Bachschmid M. Prostacyclin in the cardiovascular system: new aspects and open questions. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57(Suppl):120–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Redman CW, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:499–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wolin MS, Ahmad M, Gupte SA. The sources of oxidative stress in the vessel wall. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1659–1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Dugo L, Di Paola R, Caputi AP, Salvemini D. Superoxide: a key player in hypertension. Faseb J. 2004;18:94–101. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0428com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.van der Loo B, Koppensteiner R, Luscher TF. How do blood vessels age? Mechanisms and clinical implications. Vasa. 2004;33:3–11. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.33.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Miller FJ, Jr, Gutterman DD, Rios CD, Heistad DD, Davidson BL. Superoxide production in vascular smooth muscle contributes to oxidative stress and impaired relaxation in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 1998;82:1298–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.12.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang Y, Walsh SW. Placental mitochondria as a source of oxidative stress in pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 1998;19:581–586. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(98)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stout AK, Raphael HM, Kanterewicz BI, Klann E, Reynolds IJ. Glutamate-induced neuron death requires mitochondrial calcium uptake. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:366–373. doi: 10.1038/1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Keller JN, Kindy MS, Holtsberg FW, St Clair DK, Yen HC, Germeyer A, Steiner SM, Bruce-Keller AJ, Hutchins JB, Mattson MP. Mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase prevents neural apoptosis and reduces ischemic brain injury: suppression of peroxynitrite production, lipid peroxidation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 1998;18:687–697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00687.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kruman I, Guo Q, Mattson MP. Calcium and reactive oxygen species mediate staurosporine-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 1998;51:293–308. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980201)51:3<293::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Radi R, Cassina A, Hodara R, Quijano C, Castro L. Peroxynitrite reactions and formation in mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1451–1464. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Kerby JD, Beckman JS, Thompson JA. Nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in chronic rejection of human renal allografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11853–11858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Macmillan-Crow LA, Cruthirds DL. Invited review: manganese superoxide dismutase in disease. Free Radic Res. 2001;34:325–336. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pittman KM, MacMillan-Crow LA, Peters BP, Allen JB. Nitration of manganese superoxide dismutase during ocular inflammation. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:463–471. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.van der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, Bachschmid M, Kilo J, Powell JM, Palacios-Callender M, Erusalimsky JD, Quaschning T, Malinski T, Gygi D, Ullrich V, Luscher TF. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1731–1744. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Justilien V, Pang JJ, Renganathan K, Zhan X, Crabb JW, Kim SR, Sparrow JR, Hauswirth WW, Lewin AS. SOD2 knockdown mouse model of early AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4407–4420. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jackson RM, Helton ES, Viera L, Ohman T. Survival, lung injury, and lung protein nitration in heterozygous MnSOD knockout mice in hyperoxia. Exp Lung Res. 1999;25:631–646. doi: 10.1080/019021499270060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ishihara N, Matsuo H, Murakoshi H, Laoag-Fernandez JB, Samoto T, Maruo T. Increased apoptosis in the syncytiotrophoblast in human term placentas complicated by either preeclampsia or intrauterine growth retardation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:158–166. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Riobo NA, Clementi E, Melani M, Boveris A, Cadenas E, Moncada S, Poderoso JJ. Nitric oxide inhibits mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone reductase activity through peroxynitrite formation. Biochem J. 2001;359:139–145. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Murray J, Taylor SW, Zhang B, Ghosh SS, Capaldi RA. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial complex I due to peroxynitrite: identification of reactive tyrosines by mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37223–37230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jekabsone A, Ivanoviene L, Brown GC, Borutaite V. Nitric oxide and calcium together inactivate mitochondrial complex I and induce cytochrome c release. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:803–809. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, McDonald S, Redelmeier DA. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of placental dysfunction. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]