Abstract

HCV-796 is a nonnucleoside inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) nonstructural protein 5B (NS5B) polymerase, and boceprevir is an inhibitor of the NS3 serine protease. The emergence of replicon variants resistant to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir was evaluated. Combining the inhibitors greatly reduced the frequency with which resistant colonies arose; however, some resistant replicon cells could be isolated by the use of low inhibitor concentrations. These replicons were approximately 1,000-fold less susceptible to HCV-796 and 9-fold less susceptible to boceprevir. They also exhibited resistance to anthranilate nonnucleoside inhibitors of NS5B but were fully sensitive to inhibitors of different mechanisms: a pyranoindole, Hsp90 inhibitors, an NS5B nucleoside inhibitor, and pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN). The replicon was cleared from the combination-resistant cells by extended treatment with Peg-IFN. Mutations known to confer resistance to HCV-796 (NS5B C316Y) and boceprevir (NS3 V170A) were present in the combination-resistant replicons. These changes could be selected together and coexist in the same genome. The replicon bearing both changes exhibited reduced sensitivity to inhibition by HCV-796 and boceprevir but had a reduced replicative capacity.

An estimated 170 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and are at risk for the development of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (26, 38, 39). The current standard of care for chronic HCV infection is prolonged treatment with a combination of pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN) and ribavirin. For the genotype 1 strains, which are the most prevalent in the developed world, this regimen achieves a sustained virologic response in only about 50% of treated patients, is poorly tolerated, and requires injection (6, 24, 32). There is an urgent need for a treatment that is more effective, less toxic, and easier to administer than the present therapy.

HCV is an enveloped RNA virus and a member of the Hepacivirus genus of the family Flaviviridae (for a review, see reference 21). HCV isolates can be classified into six genotypes, which can be subdivided into more than 70 subtypes (34). A further level of diversity is apparent within an infected individual, where the viral population exists as a quasispecies. The heterogeneity of HCV is due to the high rate of replication, approximately 1012 virions per day (28), and the error-prone nature of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). If treatment does not completely suppress replication, these factors are likely to result in the rapid selection of drug-resistant HCV variants. Knowing the basis of resistance, as well as the nature and the fitness of resistant variants, will aid the design of drugs that may not be readily circumvented by the virus. For all small-molecule anti-HCV compounds characterized to date, a single mutation in the target gene was sufficient to significantly reduce the susceptibility of the HCV replicon. Such mutations have often been associated with deleterious effects on the replicative capacity of the replicon. The fitness of resistant mutants is likely to be a critical determinant of the efficacy of an anti-HCV therapy.

The nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) serine protease, with its cofactor NS4A, is responsible for cleavage of the HCV polyprotein at sites downstream of NS3. Clinical trials have validated the NS3 protease as an antiviral target in infected patients. Telaprevir (VX-950) and boceprevir (SCH-503034) are peptidic ketoamide inhibitors of the NS3 protease that are currently being developed for the treatment of HCV (31, 33). Results from replicon resistance studies, confirmed in biochemical assays, revealed that single amino acid mutations were capable of reducing susceptibility to these protease inhibitors. For example, the NS3 mutation V170A reduced susceptibility to boceprevir (35).

Nucleoside inhibitors (NIs) and nonnucleoside inhibitors (NNIs) of the NS5B RdRp have been reported. The validation of NS5B as a therapeutic target was demonstrated with the NI valopicitabine (NM283; Idenix), a prodrug of 2′-C-methylcytidine (7). Following conversion to the active 5′-triphosphate, NIs function as competitive substrate analogs that terminate nascent RNA chains (for a review, see reference 4). Numerous structurally diverse NNIs that bind to multiple sites on NS5B have been reported (for recent reviews, see references 5, 15, and 40). NNIs may act through allosteric mechanisms that inhibit the initiation of synthesis or the elongation of RNA by NS5B. Similar to the protease inhibitors, single amino acid changes reduce susceptibility to the NIs and NNIs characterized to date.

HCV-796 is a benzofuran NNI with potent and specific activity against the HCV RdRp, inhibiting RNA synthesis in both cell-free and replicon assays (14a). HCV-796 binds near the NS5B active site. Changes in amino acids adjacent to the active site conferred reduced susceptibility to HCV-796, with a major resistance mutation generated in the replicon being C316Y (12). In phase 1b studies, the combination of HCV-796 with Peg-IFN and ribavirin resulted in an enhanced antiviral activity and an ∼3.3-log-unit reduction in HCV RNA levels in infected patients (37). The clinical development of HCV-796 was, however, halted due to elevations in liver enzyme levels in the blood of some patients after prolonged treatment. Efforts to eliminate the side effects in this class of inhibitors may yet yield clinically useful compound.

An optimal anti-HCV regimen is likely to include several drugs targeting different steps in replication, to achieve maximal efficacy and curtail the development of resistance. Previously, we demonstrated that the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir had an additive inhibitory effect on the HCV replicon (14). In the study described here, we used the HCV replicon to investigate the resistance that might arise upon treatment with this combination. We report that while the combination reduces the frequency with which resistant replicons arise, variants with reduced susceptibility to both agents can be isolated at suboptimal compound concentrations. The mutations responsible for this reduced susceptibility were identified and characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and materials.

Huh7, Huh7.5, and Huh7-BB7 cells bearing the Con1 strain (genotype 1b) subgenomic HCV replicon and the parental plasmid pHCVrep1b.BB7 were licensed from Apath, LLC (St Louis, MO). Cell monolayers were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT), nonessential amino acids, and penicillin-streptomycin. For the Huh7-BB7 cells, the medium was supplemented with 1 mg/ml Geneticin (G418; Invitrogen). PEG-intron, was obtained from Schering Corporation (Kenilworth, NJ), 2′-C-methylcytidine was obtained from Chemos GmbH (Regenstauf, Germany), and 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Frequency of emergence of resistant colonies.

Huh7-BB7 cells were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells per 100-mm dish in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS, 1 mg/ml G418, and various concentrations of HCV-796 and/or boceprevir with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a final concentration of 0.5% (vol/vol). The medium was removed and was replaced with fresh medium with the appropriate compound concentrations every 3 or 4 days. After 7 days, the cells were split 1 to 10, placed into fresh 100-mm dishes, and incubated with medium with the appropriate compound concentrations. After 20 days, the medium was removed and the cells were fixed with 7% (wt/vol) formaldehyde and stained with 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet in 50% (vol/vol) ethanol.

Selection of replicon variants resistant to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir.

Huh7-BB7 cells were seeded at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells per 25-cm2 tissue culture flask and cultured without G418 in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS, penicillin-streptomycin, 0.5% (vol/vol) DMSO, and various combinations of compounds. When the cells reached about 80% confluence (about 2 to 3 days), the cultures were split 1 to 3 and placed into fresh medium containing the appropriate compound concentrations. Each time that the cultures were passaged, 100,000 cells were collected, lysed with RLT buffer (RNeasy 96 kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and stored at −70°C until they were processed. The lysates were thawed; and the total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy 96 kit, eluted in nuclease-free water, and used for quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (qRT-PCR). To select for resistant replicons, following a 2-week treatment period, the cells were passaged in the presence of the appropriate concentrations of compounds, but with 0.33 mg/ml G418. Some cell death was observed 7 to 10 days following the addition of G418, but the surviving cells were allowed to grow back to confluence. Resistant colonies were selected and enriched by repeating this process and successively increasing the G418 concentration to 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 mg/ml. Subsequently, the selected cell populations were propagated in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS, the appropriate concentrations of HCV-796 and boceprevir, 1 mg/ml G418, and 0.5% (vol/vol) DMSO.

HCV replicon inhibition.

The 3-day assay for replicon inhibition was described previously (11). Briefly, cells were seeded at 7,000 cells per well of a 96-well plate in DMEM with 2% FBS and without G418. The compound under test was solubilized in 100% DMSO and was added to the wells as a 10-point two- or threefold dilution series to a final DMSO concentration of 0.5% (vol/vol). The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 days. After 3 days, the medium was removed and the total RNA was extracted by using the RNeasy 96 kit. The extracted RNA was eluted in nuclease-free water; and the amounts of HCV RNA, rRNA, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RNA were determined by qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCR was performed with an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as described previously (11). Briefly, 18S rRNA and HCV replicon RNA were quantified in a single-step duplexed reaction with rRNA predevelopment reagent and primers and probe specific for the neomycin phosphotransferase gene (Applied Biosystems), respectively. The RT reaction was carried out at 48°C for 30 min, followed by a denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min. The PCR amplification was conducted in 40 cycles, each of which was 95°C for 15 s followed by 60°C for 1 min. The amount of GAPDH RNA was determined in a separate reaction by using the GAPDH predevelopment reagent mix (Applied Biosystems). Total RNA extracted from replicon-bearing cells was used to construct standard curves. HCV RNA copies were quantified by the National Genetics Institute, and the total RNA concentration was determined by UV spectrophotometry. The amount of HCV RNA, 18S rRNA, or GAPDH RNA in each sample was determined by comparison to the standard curves and was expressed as the number of HCV RNA copies per μg of total RNA (by using rRNA as a marker for total RNA measurement) or the amount of GAPDH RNA relative to the amount of total RNA.

Replicon clearance assay with Peg-IFN.

The replicon clearance assay was done essentially as described previously (3, 19, 20). Resistant replicon cells obtained from selection with 40 nM HCV-796 plus 800 nM boceprevir were passaged twice in the absence of G418 and were then treated with 0, 110, or 1,100 ng/ml Peg-IFN for 30 days without G418 but with 40 nM HCV-796 and 800 nM boceprevir. Confluent monolayers were passaged every 3 to 4 days. Each time that the cells were split, a sample of 100,000 cells was lysed for qRT-PCR. To allow for receptor recycling and to prevent cell-signaling tolerization, at each passage the cultures were seeded into medium without Peg-IFN and were incubated for 24 h, and then Peg-IFN was added. After 30 days, the Peg-IFN was withdrawn and 0.25 mg/ml G418 was added to expand the cells that had not cleared the replicon. After approximately 7 days of treatment with G418, cell death was observed in several of the cultures. The surviving cells were permitted to grow back to confluence in the presence of 0.25 mg/ml G418; and the amounts of HCV RNA, rRNA, and GAPDH RNA were determined by qRT-PCR.

Replicon sequence analysis.

Total cellular RNA was extracted from replicon cells with the RNeasy purification system (Qiagen). For population sequencing of the HCV nonstructural genes, cDNA was synthesized with the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR system with Platinum Taq High-Fidelity enzyme (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was carried out in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 0.1 to 0.3 μg of total cellular RNA, 200 nM of each forward and reverse primer, 0.4 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.4 mM of magnesium sulfate in the buffer provided. The reaction mixture was incubated at 55°C for 30 min and 94°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 2 min and a final extension at 68°C for 7 min. The RT-PCR products were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis and were then purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) before sequencing.

To generate single RT-PCR products encompassing NS3 to NS5B, RT was performed with total cellular RNA, oligonucleotide A9412 (5′-CAGGATGGCCTATTGGCCTGGAG-3′), and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) at 55°C for 1 h. The RNA strands were removed by the addition of RNase H (2 U per reaction mixture) and incubation at 37°C for 20 min. A 6.4-kb product was then amplified according to the manufacturer's instructions with the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) with oligonucleotides 1419F (5′-GGTCTGTTGAATGTCGTGAAGGAA-3′) and 7761R (5′-CGTTCATCGGTTGGGGAGTA-3′) by using Expand Long Template Buffer 1 and 1 μl of the RT reaction mixture. Cycling conditions were as described previously (22). To avoid potential RT-PCR bias, seven independent PCRs were performed; and the amplicons were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis, pooled, and cloned with a Zero-Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen). The sequences of the inserts were determined by standard procedures.

Cloning and mutagenesis.

An HCV replicon expressing a secreted luciferase protein was constructed by replacing the neo gene of plasmid pHCVrep1b.BB7 with the luciferase gene from Gaussia princeps, amplified from pCMV-G-luc (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), to generate plasmid pHCVrep1b.BB7.G-luc. Following transcription and electroporation of the replicon RNA encoded by this plasmid, the Gaussia luciferase protein was secreted from cells that expressed the protein and the activity could be measured in the culture medium. Mutagenesis was performed with a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Mutations were generated in the appropriate shuttle vector, pMUT-middle (which contains the BsrGI-XhoI fragment from pHCVrep1b.BB7 and encompasses part of NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and most of NS5A) or pMUT-back (which contains the XhoI-HindIII site from pHCVrep1b.BB7 and encompasses part of NS5A, NS5B, and the 3′ untranslated region). The fragments of interest were subcloned back into the appropriate replicon vector: either pHCVrep1b.BB7 for the generation of stable cell lines or pHCVrep1b.BB7.G-luc for transient expression. The presence of each mutation was confirmed by sequencing of the final replicon plasmids. Amino acid mutations were designated by the single-letter amino acid code of the parental sequence, the residue number of the individual protein, and the altered amino acid present in the mutant construct.

RNA transcription and electroporation of cultured cells.

In vitro transcription was performed with a T7 MEGAScript kit (Applied Biosystems) and plasmid DNA templates linearized with ScaI. Following treatment with RNase-free DNase and purification with the RNeasy purification kit (Qiagen), the RNA yield was determined by quantification with a UV spectrophotometer. Subconfluent monolayers of Huh7.5 cells grown in 225-cm2 flasks were trypsinized and resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and the viable cell count was determined by trypan blue exclusion. The cells were washed twice by centrifugation at 250 × g for 5 min and resuspension in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (50 ml per flask) at room temperature and were then pelleted again and resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml in Cytomix [120 mM potassium chloride, 0.15 mM calcium chloride, 2 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 5 mM magnesium chloride, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.6]. A total of 4 × 106 cells were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, and ATP (100 mM in Cytomix) and glutathione (100 mM in water) were added to final concentrations of 2 and 5 mM, respectively. Ten micrograms of replicon RNA was then added to each tube, and the contents were mixed briefly and transferred to an electroporation cuvette with a 0.4-cm gap (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The cells were electroporated with a Gene Pulser II apparatus (Bio-Rad) at 950 μF and 270 V and were then immediately transferred to either 45 ml or 30 ml DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for colony formation and transient replication assays, respectively.

Efficiency of colony formation.

Following the electroporation of Huh7 cells with RNA generated from pHCVrep1b.BB7 templates, a 10-fold serial dilution of the electroporated cells was generated; and 15 ml of each of the 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1,000 dilutions (∼105, 104, and 103 electroporated cells, respectively) was seeded in 100-mm dishes. To select for replicon-bearing cells, the culture medium was supplemented with G418 at 0.375 mg/ml. To determine the efficiency of colony formation, the medium was removed; the cells were then fixed with formaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. Cell colonies were counted by using a Sorcerer image analysis system (Perceptive Instruments Ltd., Haverhill, United Kingdom), and the efficiency of colony formation was expressed as the number of CFU per μg of electroporated RNA.

Transient replication assay.

Following the electroporation of Huh7.5 cells with RNA generated from pHCVrep1b.BB7.G-luc templates, 0.1 ml of electroporated cells was seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. To determine the susceptibility of mutant replicons to inhibition by compounds, the medium was removed 48 h after electroporation and replaced with DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS and the compound under test. At 72 h after compound addition, samples of the cell culture medium were taken and the luciferase activity from 25 μl of culture medium was measured by using the Gaussia luciferase assay kit (New England Biolabs). The 50% effective concentration (EC50) was defined as the compound concentration necessary to inhibit 50% of the luciferase activity from untreated cells, after the subtraction of the background signal.

RESULTS

Use of a combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir reduces the frequency with which resistant variants emerge.

Individually, HCV-796 and boceprevir demonstrate anti-HCV activity in patients and on the HCV replicon. Combining the two compounds had an additive inhibitory activity on the replicon, and mutants resistant to one agent were fully susceptible to the other (14), suggesting that use of the combination might enhance antiviral efficacy while diminishing the selection of resistant variants. We used the HCV replicon to study whether resistance might arise upon treatment with both HCV-796 and boceprevir.

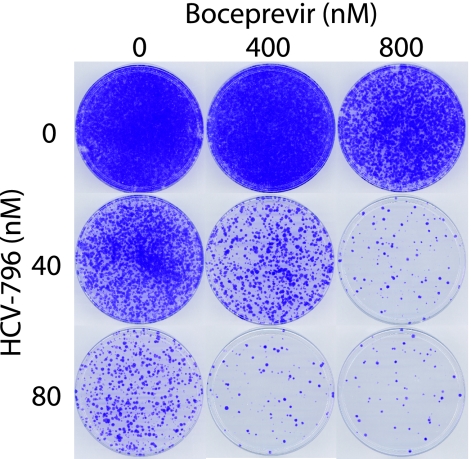

To determine if the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir affected the frequency with which resistant replicons emerged, a genotype 1b subgenomic HCV replicon with the neo selectable marker was used. Replicon cells were treated with 1 mg/ml G418 and combinations of the two compounds. HCV-796 was added to 40 or 80 nM (approximately 10 and 20 times the EC50 in a 3-day replicon inhibition assay, respectively) and boceprevir was added to 400 or 800 nM (approximately 2 and 4 times the EC50, respectively). The combinations are hereafter referred to as the nM concentration of HCV-796/the nM concentration of boceprevir (e.g., 40/800 refers to cell populations treated with 40 nM HCV-796 and 800 nM boceprevir). After 27 days of culture in the presence of compounds and G418, the surviving cell colonies were fixed and stained with crystal violet (Fig. 1). A confluent cell monolayer was apparent in the DMSO-only, vehicle control cells (0/0 cells), while increasing HCV-796 or boceprevir concentrations caused a decrease in the number of surviving colonies. The number of colonies was further reduced when the compounds were added together. Thus, replicon cells capable of growth in the presence of HCV-796 and boceprevir were isolated, but the frequency with which such variants arose was reduced by the use of a combination of the two compounds.

FIG. 1.

Frequency of selection of replicons resistant to combinations of HCV-796 and boceprevir. Huh7-BB7 cells bearing a subgenomic genotype 1b HCV replicon were seeded at 20,000 per 100-mm dish and treated with 1 mg/ml G418 and the indicated combinations of HCV-796 and boceprevir. Fresh medium, G418, and compounds at the appropriate concentration were added every 3 or 4 days. After 7 days, the cultures were split 1:10 and placed into a new 100-mm dish, and after 20 days, the surviving cell colonies were fixed and stained with crystal violet. A representative of the results of three independent experiments is shown.

Selection of HCV replicon variants resistant to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir.

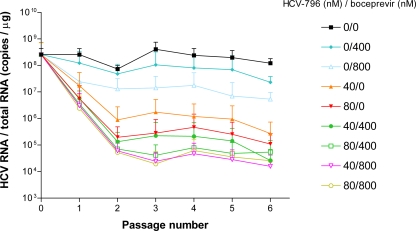

After establishing suitable concentrations of HCV-796 and boceprevir for the selection of resistant colonies (Fig. 1), we performed selection experiments to obtain resistant replicon variants. Replicon cells were cultured with HCV-796 and boceprevir, alone or in combination, but in the absence of G418. Three independent cultures were propagated for each combination tested. The cells were passaged and fresh medium and compounds were added every 2 or 3 days. At each passage, samples were analyzed to determine the HCV RNA, 18S rRNA, and GAPDH RNA levels.

For each culture, the levels of GAPDH RNA and rRNA remained approximately constant over the course of the experiment (data not shown). The control 0/0 cells showed little change in their HCV replicon contents; however, treatment with each compound alone caused dose- and time-dependent reductions in the HCV RNA level (Fig. 2). The use of a combination of the compounds enhanced the magnitude of this reduction; by the second passage, the HCV RNA levels were reduced by approximately 1 log unit in the 0/800 cells and 2 log units in the 40/0 cells but were reduced by ≥3 log units in the 40/800 cells.

FIG. 2.

Time course of treatment of HCV replicon cells with combinations of HCV-796 and boceprevir. HCV replicon cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells per 25-cm2 flask and propagated in the presence of combinations of HCV-796 and/or boceprevir, but in the absence of G418. Cells were passaged every 2 to 3 days, and each time that the cultures were split, a sample of the cells was taken. RNA was extracted from the cell lysates, and HCV and rRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR. rRNA was used as a marker for total RNA, as described in Materials and Methods. Each point is a mean HCV RNA/total RNA value from three independent experiments. The error bars above each point represent the standard errors of the means.

To select for replicon variants resistant to the combination of the two compounds, following six passages (∼18 days) without G418, the medium was gradually supplemented with increasing amounts of G418 (as described in Materials and Methods). Cells were enriched from each of the cultures treated with HCV-796 or boceprevir alone and from the cultures treated with the 40/400 and 40/800 combinations. By use of this selection procedure, no cells survived the 80/400 or the 80/800 treatments.

The ability of cell populations to grow in the presence of both HCV-796 and boceprevir was consistent with the selection of replicon variants with reduced sensitivity to both compounds. The susceptibility of these cells to the individual compounds was determined in a 3-day inhibition assay (Table 1). Untreated cells and 0/0 cells were also tested. No significant effect on GAPDH RNA or 18S rRNA levels in response to either compound was detected for any of the cultures (data not shown). The 40/400 and 40/800 cells were approximately 1,000-fold less susceptible to HCV-796 than the untreated or 0/0 cells. Similarly, these cultures were approximately 10-fold less susceptible to boceprevir than the untreated or 0/0 cells.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of replicon variants selected with a combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir to the individual compoundsa

| Concn (nM) used for cell selection

|

Replicon susceptibility

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV-796 (nM) | Boceprevir (nM) | HCV-796

|

Boceprevir

|

||

| EC50 ± SD (nM) | Fold resistance | EC50 ± SD (nM) | Fold resistance | ||

| —b | — | 4.6 ± 3.7 | — | 201 ± 8.7 | — |

| 0 | 0 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1 | 165 ± 25 | 1 |

| 40 | 400 | 2,459 ± 601 | 1,025 | 1,328 ± 305 (4) | 8 |

| 40 | 800 | 3,368 ± 1,068 | 1,403 | 1,577 ± 598 (4) | 10 |

Replicon-bearing cell populations, selected under the indicated treatments, were tested for their susceptibility to HCV-796 or boceprevir in a 3-day inhibition assay. The mean EC50 ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent determinations is shown, unless indicated otherwise in parentheses. The level of resistance relative to that of the 0/0 culture is shown.

—, untreated cells.

Susceptibility of replicons resistant to HCV-796 and boceprevir to diverse anti-HCV agents.

Multiple classes of HCV inhibitors have been discovered. To evaluate their utility against HCV variants resistant to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir, inhibitors with diverse mechanisms were tested against the 0/0 and 40/800 cells.

Inhibitors of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) also inhibit the HCV replicon (27, 30). The susceptibilities of the 0/0 and 40/800 cells to two Hsp90 inhibitors, geldanamycin and 17-DMAG, were not significantly different (Table 2; note that the variability of the EC50s for the compound-treated cells is three- to fourfold). Cytotoxicity was apparent for cells treated with both these Hsp90 inhibitors, which may account for the large variability in the EC50s (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility of replicons resistant to a combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir to different anti-HCV compoundsa

| Compound | Class | EC50b

|

Fold resistancec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells selected with 0/0 | Cells selected with 40/800 | |||

| Geldanamycin | Hsp90 inhibitor | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 1.2 ± 0.65 | 5 |

| 17-DMAG | Hsp90 inhibitor | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 3 |

| HCV-371 | Pyranoindole | 4,832 ± 1,077 (5) | 7,840 ± 2145 (2) | 2 |

| 14i | Anthranilate | 1,308 ± 267 | >20,000 | >15 |

| 14j | Anthranilate | 499 ± 269 | >15,000 | >30 |

| 2′-C-Methylcytidine (NM107) | Nucleoside | 1,143 ± 177 (5) | 1,623 ± 736 (4) | 1 |

| Peg-IFN | Inducer of innate immunity | 14.0 ± 11.7 | 16.9 ± 4.4 | 1 |

Replicon cell populations selected with the 0/0 or 40/800 treatments were tested for their susceptibility to miscellaneous HCV inhibitors in a 3-day inhibition assay.

The mean EC50 ± standard deviation from three independent determinations is shown, unless indicated otherwise in parentheses. EC50s are shown in nM for each compound except Peg-IFN, for which the EC50 is in ng/ml.

The fold resistance relative to that of the 0/0 control culture is shown.

HCV-371 is a pyranoindole NNI that binds to the thumb domain of NS5B and that inhibits RdRp activity (8, 11, 13). The 0/0 and 40/800 cells were similarly sensitive to HCV-371 (Table 2), indicating that the 40/800 cell replicons were not cross-resistant to HCV-371. In contrast, the 40/800 cells were much less sensitive (>15-fold) to inhibition by anthranilate derivatives than the 0/0 cells. Anthranilate derivatives are also NNIs of NS5B but bind approximately 7.5 Å from the active site (29). Both compound 14i and compound 14j, derivatives obtained through optimization of this inhibitor series, showed reduced potency against the 40/800 cells. 2′-C-Methylcytidine (NM107), the active component of valopicitabine (NM283), is an NI of NS5B with clinical efficacy. No significant difference in susceptibility to NM107 was observed between the 0/0 and the 40/800 cells.

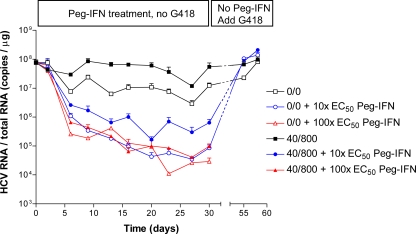

Since treatment with Peg-IFN plus ribavirin is the current standard of care for HCV infection, we assessed whether Peg-IFN was active against HCV variants resistant to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir. The 0/0 and 40/800 cells were equally susceptible to Peg-IFN (Table 2). We next determined if Peg-IFN could clear the replicon from these cells, using a protocol similar to that used to demonstrate replicon clearance by VX-950 (19, 20). Over a period of 30 days, the 40/800 cells were treated with 0, 110, or 1,100 ng/ml Peg-IFN (approximately equivalent to 0×, 10×, and 100× EC50 determined in the 3-day replicon inhibition assay), in the absence of G418. The cells grew normally and were split every 2 or 3 days, and at each passage a sample of cells was collected and HCV RNA and 18S rRNA levels were quantitated. After 30 days, the Peg-IFN was withdrawn and 0.25 mg/ml G418 was added to expand any cells that retained the replicon. Each untreated cell culture grew normally and, when the cells were assayed after 55 and 58 days, contained HCV RNA levels similar to those detected on day 0 (Fig. 3). For the cells treated with 10× EC50 Peg-IFN, cell death was apparent approximately 7 days after the addition of G418. Some cells survived, however, and grew to confluence; when assayed at 55 days, the HCV RNA level in these cells had returned to levels similar to those detected on day 0. Thus, the replicon had not been cleared from this cell population. In contrast, when G418 was added to the cells treated with 100× EC50 Peg-IFN, cell death occurred after 7 days and no cells survived, suggesting that Peg-IFN had succeeded in clearing the replicon from these cells.

FIG. 3.

HCV replicon variants resistant to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir can be cleared by Peg-IFN. A previously selected 40/800 cell population was seeded at 1 × 106 cells per 25-cm2 flask, cultured for 30 days in the presence of 40 nM HCV-796 and 800 nM boceprevir, and treated with Peg-IFN, as described in Materials and Methods. After 30 days, the Peg-IFN was withdrawn and 0.25 mg/ml G418 was added to select for cells that had retained the replicon. Three replicate cultures were treated, and HCV RNA and rRNA were quantified. rRNA was used as a marker for total RNA, as described in Materials and Methods. The mean HCV RNA/total RNA value at each time point was plotted. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means. No cells that were treated with 100× EC50 Peg-IFN survived the selection process.

Mapping amino acid changes in replicons resistant to HCV-796 and boceprevir.

To identify the mutations responsible for reduced susceptibility to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir, the sequences of the nonstructural genes from the selected replicon cell lines were determined.

The individual NS3/4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B genes were amplified and the population sequences of the RT-PCR products from at least two independently selected replicon cultures were determined. The inferred amino acid sequences were compared to the sequence from the parental replicon plasmid and are summarized in Table 3. No mutations of note were detected in NS4A, NS4B, or NS5A or in the NS3-protease cleavage sites; but differences from the originating plasmid sequence, present in multiple cultures, were found in NS3 and NS5B.

TABLE 3.

Sequences from cells selected with combinations of HCV-796 and/or boceprevir by population sequence analysis and clonal sequence analysis of nonstructural genes

| Type of analysis and culture or clone | NS3 amino acid at position:

|

NS5B amino acid at position:

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 86 | 158 | 170 | 176 | 260 | 282 | 344 | 583 | 316 | 353 | 424 | 440 | 445 | 572 | |

| Population sequence analysisa | ||||||||||||||

| 0/0-A | ||||||||||||||

| 0/0-B | Q/R | |||||||||||||

| 0/400-A | Q/R/K | T/K/E/A | ||||||||||||

| 0/400-B | Q/R | E/G | ||||||||||||

| 0/400-C | Q/R | E/G | T/K/E/A | |||||||||||

| 0/800-A | Q/R | V/A | E/G | T/K/E/A | ||||||||||

| 0/800-B | Q/K | V/A | E/G | T/K | I/V | L/F | ||||||||

| 0/800-C | Q/K | V/A | E/G | G/S | T/K | |||||||||

| 40/0-A | Q/R | M/V | E/G | T/A | G/S | T/I | G | C/F | ||||||

| 40/0-B | Q/K | M/V | G | G/S | T/K | C/Y | C/F | |||||||

| 40/0-C | M/V | G | G/S | C/Y | C/F | |||||||||

| 80/0-A | R | A | E | E/G | F | L | ||||||||

| 80/0-B | G | Y | ||||||||||||

| 80/0-C | Q/R | E/G | T/A | Y | ||||||||||

| 40/400-A | Q/R | K/E | C/Y | |||||||||||

| 40/400-B | Q/R | Y | L/P | I/V | ||||||||||

| 40/400-C | K/E | Y | I/V | |||||||||||

| 40/800-A | M | G | Y | L/P | I/V | |||||||||

| 40/800-B | M | G | —b | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||

| 40/800-C | A | G/S | Y | |||||||||||

| pBB7 | Q | V | V | E | T | G | T | K | C | P | I | E | C | F |

| Polyprotein | 1112 | 1184 | 1196 | 1202 | 1284 | 1308 | 1370 | 1609 | 2735 | 2772 | 2843 | 2859 | 2864 | 2991 |

| Clonal sequence analysisc | ||||||||||||||

| 0/0-A #1 | R | |||||||||||||

| 0/0-A #2 | R | Q | ||||||||||||

| 0/0-A #3 | E | |||||||||||||

| 0/0-A #4 | R | E | ||||||||||||

| 0/0-A #5 | ||||||||||||||

| 40/800-A #1 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-A #2 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-A #3 | G | R | Y | L | V | |||||||||

| 40/800-A #4 | I | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-A #5 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-B #1 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-B #2 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-B #3 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-B #4 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-B #5 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-C #1 | A | Y | ||||||||||||

| 40/800-C #2 | M | G | A | I | G | F | L | |||||||

| 40/800-C #3 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-C #4 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| 40/800-C #5 | M | G | S | Y | L | V | ||||||||

| pBB7 | Q | V | V | E | T | G | T | K | C | P | I | E | C | F |

| Polyprotein | 1112 | 1184 | 1196 | 1202 | 1284 | 1308 | 1370 | 1609 | 2735 | 2772 | 2843 | 2859 | 2864 | 2991 |

RNA from independently selected replicon cultures (A, B, and C) was extracted; and the genes for the nonstructural proteins NS3/NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B were amplified and sequenced. Sporadic amino acid changes that were present in only a single culture are not shown, nor are changes from the parental sequence that were present in all the cultures (including the control-treated cells). Polymorphisms were assigned by visual appraisal of the sequence chromatograms.

—, not performed.

RNA from independently selected replicon cultures (0/0-A or 40/800-A, -B, or -C) was extracted, and the cDNA encoding the nonstructural coding region was amplified and cloned. Five different clones derived from each selected culture (clones 1 to 5) were sequenced. Only amino acid positions noted as being of interest from the population sequencing are shown. Amino acid numbering within NS3 and NS5B, the predicted amino acids present in the parental pBB7 plasmid, and polyprotein numbering according to the Con1 sequence (GenBank accession no. AJ238799) are shown.

Two previously reported cell-culture-adaptive mutations were found in the selected replicons: NS3 Q86R (2) and E176G (16). These adaptive mutations may compensate for debilitated sequences, restoring replicon fitness. The NS3 E176G mutation was not found in the 0/0 cells but was detected in the majority of the compound-treated replicons, suggesting that it may have been coselected with resistance mutations that cause a debilitation in replicative capacity. The NS3 V170A mutation confers resistance to boceprevir (35) and was detected in three of three cultures selected with 0/800 and in one of three cultures selected with 40/800, although it was not detected in the 0/400 or 40/400 cells. This suggests that boceprevir at 800 nM, but not 400 nM, exerted sufficient selective pressure for the V170A mutation to emerge. Changes at A156, associated with high-level resistance to NS3 protease inhibitors, were not detected in any of the cultures treated with boceprevir, either alone or in combination with HCV-796, probably due to the low compound concentrations used. An important resistance mutation for HCV-796 is NS5B C316Y. This change was found in replicons selected with HCV-796, either alone or in combination with boceprevir. The mutation NS5B C445F was detected in replicons treated with HCV-796 alone. This change was previously reported as being present in replicons selected with anthranilates or HCV-796 (12), but its phenotype was not characterized. To determine if the NS3 and the NS5B mutations were present together in the same genome, we amplified, cloned, and sequenced the entire nonstructural region from the three 40/800 cultures (40/800-A, -B, and -C, respectively). Five clones from each culture were sequenced. Several sporadic mutations, present in only a single clone, were identified but were not investigated further. The amino acid positions identified as being of interest by the population sequencing are shown in Table 3. For NS3, the protease domain consists of the N-terminal approximately 180 amino acids, and the ATPase/helicase region constitutes the remaining C-terminal sequence (for reviews, see references 1 and 21). The results of the clonal sequencing of the 40/800 replicon cells were generally consistent with those of the population sequencing, with NS3 V158M, E176G, and G282S and NS5B C316Y, P353L, and I424V being notably prevalent among the sequenced clones. The HCV-796 resistance mutation NS5B C316Y was found in 13 of the 14 clones sequenced. The boceprevir resistance mutation NS3 V170A was found in only a single clone from the 40/800 cell cultures (Table 3, 40/800-C #1), which also carried NS5B C316Y, indicating that these two resistance mutations can coexist in the same replicon genome. Only one clone did not carry the NS5B C316Y mutation, and this particular clone (40/800-C #2) also carried changes in NS5B (NS5B C445F, E440G, and F572L) that were not present in any of the other clones.

In summary, amino acid changes previously shown to confer resistance to HCV-796 (NS5B C316Y) and boceprevir (NS3 V170A) as well as cell-culture-adaptive mutations (NS3 Q86R and E176G) and some changes not previously characterized were found in the selected replicons. The two primary resistance mutations NS3 V170A and NS5B 316Y coexisted in the same genome under the selection pressure of boceprevir and HCV-796. In addition to NS5B C316Y, NS3 V170A, and NS3 E176G, the following mutations were found in more than two of the selected cell cultures and were chosen for further investigation: NS3 V158M, NS3 G282S, NS3 K583T, NS5B I424V, and NS5B C445F.

Identification of mutations responsible for reduced susceptibility to HCV-796 and boceprevir.

To determine the phenotype conferred by the mutations found in replicons treated with the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir, each individual mutation was reintroduced into a parental replicon that had the neo gene replaced with luciferase from Gaussia princeps. The susceptibility of each mutant to HCV-796 and boceprevir was tested in a transient expression assay following electroporation of the replicon RNA. The Gaussia luciferase protein was secreted from expressing cells and was assayed in the culture medium 72 h after the addition of compound. The EC50s for HCV-796 and boceprevir for the parental replicon in the transient expression assay were comparable to those obtained in the 3-day inhibition assay with the stable replicon cells; the EC50 for HCV-796 in the transient expression assay was 14 nM, whereas it was 5 nM for the stable replicon; and the EC50 for boceprevir in the transient expression assay was 608 nM, whereas it was 201 nM for the stable replicon (compare the data in Table 4 and Table 1).

TABLE 4.

Characterization of individual mutationsa

| Mutation(s) | Protein(s) | HCV-796

|

Boceprevir

|

Efficiency of colony formation (103 CFU/μg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM) | Fold resistance | EC50 (nM) | Fold resistance | |||

| Parent sequence | NA | 14 ± 7 (12) | 1 | 608 ± 255 (12) | 1 | 15.0 ± 12.9 (11) |

| V158M | NS3 | 9 ± 4 (6) | 1 | 377 ± 211 (6) | 1 | 4.8 ± 4.7 (7) |

| V170A | NS3 | 13 ± 4 (9) | 1 | 3,170 ± 1,110 (9) | 5 | 14.0 ± 13.6 (8) |

| E176G | NS3 | 38 ± 23 (9) | 3 | 2,152 ± 1,028 (9) | 4 | 36.2 ± 25.7 (7) |

| G282S | NS3 | 22 (2) | 2 | 1,937 ± 182 | 3 | 26.9 ± 19.3 (5) |

| K583T | NS3 | 15 ± 9 | 1 | 738 ± 395 | 1 | 18.7 ± 16.0 (5) |

| C316Y | NS5B | 1,936 ± 779 (9) | 138 | 781 ± 504 (9) | 1 | 7.1 ± 6.1 (8) |

| I424V | NS5B | 13 ± 3 | 1 | 647 ± 105 | 1 | 5.9 ± 7.4 (8) |

| C445F | NS5B | 114 ± 26 (9) | 8 | 795 ± 473 (9) | 1 | 12.3 ± 10.0 (6) |

| V170A and C316Y | NS3 and NS5B | 1,335 ± 995 | 95 | 4,362 ± 573 | 7 | 8.3 ± 6.6 |

| C316Y and C445F | NS5B and NS5B | 25,680 ± 6,020 (6) | 1,834 | 821 ± 363 (6) | 1 | 5.9 ± 3.7 |

| Pol− | NS5B | 0 | ||||

The susceptibility of replicon mutants to HCV-796 or boceprevir was determined by using a transient luciferase replicon. The mean EC50 ± standard deviation from three independent determinations, unless indicated otherwise in parentheses, and the level of resistance compared to that of the cells with the parental replicon sequence are shown. The efficiency of colony formation was determined following electroporation of Huh7.5 cells with mutant replicon RNA and selection with G418. The efficiency of colony formation was determined for each mutant replicon in three separate electroporations on different days with independently derived RNA preparations. The mean efficiency of colony formation ± the standard deviation from three independent determinations is shown, unless indicated otherwise. The results for a replication-defective RNA (Pol−) are shown as a negative control. NA, not applicable.

In the transient expression assay, NS5B C316Y conferred a 138-fold reduced susceptibility to HCV-796 but had no effect on susceptibility to boceprevir. The NS3 V170A mutation conferred a fivefold reduced susceptibility to boceprevir but had no effect on susceptibility to HCV-796. When both of the primary resistance mutations NS3 V170A and NS5B C316Y were introduced together, the mutant with the double mutation exhibited reduced susceptibility to both compounds: 7-fold to boceprevir and 95-fold to HCV-796. The NS5B C445F mutation conferred an eightfold reduced susceptibility to HCV-796 but had no effect upon inhibition by boceprevir. The resistance to HCV-796 contributed by NS5B C316Y and C445F was more than additive, as a replicon bearing both mutations had ∼1,800-fold reduced susceptibility.

Mutants with the cell-culture-adaptive mutation NS3 E176G showed a slightly reduced susceptibility to inhibition by both HCV-796 (threefold) and boceprevir (fourfold). This was likely due to an increased replication level and not a specific mechanism of resistance. A similar mechanism may explain the slightly reduced susceptibility to both compounds conferred by NS3 G282S. Three mutations found in the selected replicons did not affect susceptibility to either HCV-796 or boceprevir in the transient expression assay: NS3 V158M, NS3 K583T, and NS5B I424V.

Characterization of mutant fitness.

The replicative fitness of resistant viral variants is likely to be a critical factor that determines whether such mutant viruses emerge during drug treatment. We attempted to use the Gaussia luciferase reporter replicons described above to determine fitness, as has been reported by others (18, 23). In these experiments, the mutants with the NS3 V158M and the NS5B I424V mutations expressed significantly less luciferase than the parental replicon, but the expression from each of the other mutants was not significantly different from that from the parental sequence (data not shown). The high degree of stability of the Gaussia luciferase protein compared to that of the firefly luciferase used by others may cause this assay to poorly resolve fitness phenotypes. Instead, we used other methods to evaluate mutant fitness.

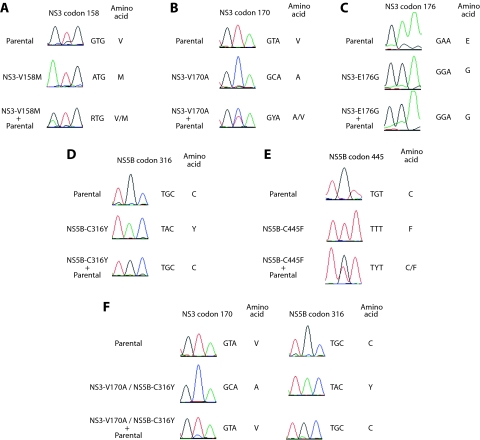

The replicative capacity relative to that of the parental replicon was determined by competition experiments between the parent and mutant replicons. Previous studies used the coculture of cells bearing parental and mutant replicons to assess relative fitness (17, 35). Since this analysis may be complicated by the relative growth rates of the replicon-bearing cell lines, which may be independent of the fitness of the replicon itself, we used an alternative method. Huh7 cells were electroporated with either the parental replicon, the mutant replicon, or equal amounts of the parental and the mutant replicons. After G418 selection and expansion (16 to 20 days after electroporation) in the absence of inhibitor selection, the NS3 and NS5B genes were amplified and sequenced to determine if the mutant or the parental sequence predominated in the selected cell population (Fig. 4). When equal amounts of the parental replicon and the mutant with the cell-culture-adaptive mutation NS3 E176G were electroporated, the predominant sequence at NS3 position 176 after selection was E176G (Fig. 4C), consistent with the cell-culture-adapted mutant possessing a competitive advantage over the parental sequence. In contrast, when the mutants with the NS3 V158M, NS3 V170A, and NS5B C445F mutations were introduced with equal amounts of the parental replicon, the resulting cell populations maintained both the parent and the mutant sequences (Fig. 4A, B, and E), suggesting that the fitness of these mutants was not significantly impaired and was similar to that of replicons with the parental sequence. These mixed replicon populations appeared to be relatively stable, as each carried both the parental and the respective mutant sequence 5 weeks after the initial sequencing (data not shown). Electroporation of the parent replicon and the mutant with the NS5B C316Y mutation yielded a replicon population that was predominantly parental (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the NS5B C316Y change debilitated fitness, and as a result, this mutant was outcompeted by the parental replicon sequence. Consistent with this, when the mutant with the double NS3 V170A and NS5B C316Y mutation was introduced together with the parental replicon, the resulting cell population predominantly bore the parental sequence at both positions (Fig. 4F), providing further evidence that reduced fitness is associated with NS5B C316Y and, consequently, the double mutation. The competition experiment was performed three times, and similar results were obtained each time, except on one occasion when the mutant with the NS5B C445F mutation electroporated alone reverted and possessed mixed mutant and parental sequences at NS5B position 445 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Competition with the parental replicon sequence as a measure of mutant relative replicative capacity. Huh7 cells were electroporated either with parental replicon RNA, mutant replicon RNA, or equal amounts of parental and mutant replicon RNAs. Following G418 selection in the absence of inhibitor selection, RNA was extracted from the replicon cell populations and the NS3 and NS5B genes were amplified. The sequences of the PCR product populations were determined. (A) NS3 V158M; (B) NS3 V170A; (C) NS3 E176G; (D) NS5B C316Y; (E) NS5B C445F; (F) NS3 V170A and NS5B C316Y. Representative sequencing chromatograms (from at least two sequencing reactions), the nucleotide sequences, and the inferred amino acid sequences at the mutant codon are shown. Sequences from cells electroporated with only the parent replicon RNA and only the mutant replicon RNA are shown above those from the coelectroporated cells.

To obtain a further measure of mutant fitness, the efficiency of colony formation following electroporation was determined (Table 4). The parental replicon had an efficiency of 15 × 103 CFU/μg of RNA. The mutations could be divided into three groups. The first group comprised those that increased the efficiency of colony formation above that of the parental replicon, including the cell-culture-adaptive change NS3 E176G, but also NS3 G282S (36 × 103 and 27 × 103 CFU/μg, respectively). The second group of mutations did not significantly alter the efficiency of colony formation and included NS3 V170A, NS3 K583T, and NS5B C445F (14 × 103, 19 × 103, and 12 × 103 CFU/μg, respectively). The final group of mutants caused a decrease in the efficiency of colony formation and included NS3 V158M, NS5B C316Y, and NS5B I424V (5 × 103, 7 × 103, and 6 × 103 CFU/μg, respectively), consistent with these changes causing a debilitation of HCV replication.

DISCUSSION

There are now more than 20 antiretroviral agents that target multiple steps in replication and that are approved for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Current guidelines suggest an initial antiretroviral therapy consisting of two NIs of the HIV reverse transcriptase, in combination with an NNI or an HIV protease inhibitor(s) (9). Such combinations provide the best chance of achieving maximal antiviral efficacy and curtailing the development of resistance. For HCV, an optimal antiviral regimen is also likely to include several drugs that target different steps in replication.

HCV-796 (an NNI of HCV NS5B) and boceprevir (an inhibitor of the NS3 serine protease) both demonstrated antiviral activity in HCV-infected patients (33, 36). In the replicon system, combinations of HCV-796 and boceprevir had an additive inhibitory effect, and variants resistant to one agent were fully susceptible to the other (14). These preclinical results suggest that combination of the two compounds might enhance clinical efficacy and diminish the possibility of the selection of resistant variants. To explore this hypothesis, we tested combinations of HCV-796 and boceprevir for their abilities to generate resistant replicon variants, determined the susceptibility of these replicon variants to anti-HCV agents with different mechanisms of action, and identified and characterized the mutations that arose in response to the combination treatment.

The frequency with which resistant colonies emerged was reduced by the use of the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir (Fig. 1), but dually resistant replicon variants could be isolated. Replicons selected in the presence of 40 nM HCV-796 and 800 nM boceprevir were resistant to both compounds (approximately 1,000-fold and 10-fold, respectively; Table 1) and also to two anthranilate derivatives (Table 2). This cross-resistance is explained by the fact that anthranilates and HCV-796 have overlapping binding sites on NS5B (data not shown). The combination-resistant replicon cells were, however, fully sensitive to inhibition by another NNI (HCV-371, a pyranoindole), as well as to the NI 2′-C-methylcytidine, inhibitors of Hsp90, and Peg-IFN. The replicon could be cleared by extended treatment with Peg-IFN (Fig. 3).

The major resistance mutation for HCV-796, NS5B C316Y, was identified in several of the replicon populations selected with HCV-796. This change was previously shown to confer an 8-fold reduced susceptibility to HCV-796 in a cell-free enzyme assay and a 166-fold reduced susceptibility in the stable replicon (12). In the transient luciferase replicon, NS5B C316Y conferred a 138-fold reduced susceptibility to HCV-796 (Table 4). The NS5B C316Y mutation was associated with a reduced replicative capacity, as the mutant was outcompeted by the parental replicon when both were introduced into cells (Fig. 4D), and the NS5B C316Y change decreased the efficiency of colony formation by approximately twofold (Table 4). These findings are consistent with those in a previous report indicating a reduced replicative capacity for this mutant (25).

A previously described boceprevir resistance mutation was found in the combination-selected replicons; NS3 V170A had little effect on the catalytic efficiency of the NS3 protease but did decrease the affinity for the compound (35). In one report of a study that used a strain N replicon, V170A increased the replication efficiency (10), but we observed that V170A had little impact on fitness, either by competition with the parent replicon (Fig. 4B) or in the colony formation assay (Table 4). The NS3 A156T mutation, which conferred the highest level of replicon resistance to boceprevir in a previous study (35), was not seen in the combination-treated replicon cells. A long exposure to, or high concentrations of, boceprevir were necessary to induce the appearance of A156 mutations (35).

The individual resistance mutations NS5B C316Y and NS3 V170A were detected by population sequencing of the NS5B and NS3 genes. To determine if replicons bearing both mutations in the same genome had arisen during the selection process, the entire nonstructural region from the 40/800 combination-resistant replicons was amplified, cloned, and sequenced. The NS3 V170A mutation was not abundant in these sequences, probably due to the low EC90 multiple (2×) of boceprevir used for selection, but we did isolate a clone that bore both the NS3 V170A and the NS5B C316Y mutations. This suggests that these two resistance mutations can be selected together and coexist in the same genome. A luciferase replicon engineered to contain both mutations exhibited resistance to both compounds in a transient expression assay. The extent of resistance in the transient expression assay was similar to that conferred by the individual mutations to their respective compounds. The fitness of the mutant with the double NS3 V170A and NS5B C316Y mutations was debilitated, as it was outcompeted by the parental replicon sequence in the competition experiment (Fig. 4F) and had a reduced efficiency of colony formation (Table 4).

The NS5B C445F mutation was detected during selection with anthranilate inhibitors of NS5B (A. Y. M. Howe et al., unpublished data) and in previous selection experiments with HCV-796 alone (12), but it was not previously characterized for its effect on susceptibility to HCV-796. In the transient luciferase replicon, NS5B C445F conferred an eightfold reduced susceptibility to HCV-796. NS5B C445F did not have a detectable effect on HCV replication, as it was not outcompeted when it was electroporated together with the parental replicon, nor did it have a significant effect on the efficiency of colony formation. While such a clone was not isolated from the combination-treated replicon cells, we were interested in determining the phenotype of a replicon bearing both NS5B C316Y and NS5 C445F. The reduced susceptibility conferred by these mutations was more than additive, as the EC50 of HCV-796 for the mutant with the double mutation was ∼1,800-fold greater than that for the parental replicon (Table 4). This suggests that the selection of the NS5B C445F mutation, together with the selection of NS5B C316Y, would result in a viral variant with high-level resistance to HCV-796. The fitness of this mutant with the double mutation was not assessed in the competition assay, but it did possess a reduced efficiency of colony formation similar to that conferred by the C316Y mutation alone.

In addition to the resistance mutations, several other changes were detected in the selected replicon cells. NS3 V158M was selected in the presence of HCV-796 alone and in combination with boceprevir but not with boceprevir alone. Similarly, NS5B I424V was selected in the presence of boceprevir alone and in combination with HCV-796 but not with HCV-796 alone. When they were reintroduced into the parental replicon sequence, neither NS3 V158M nor NS5B I424V affected susceptibility to HCV-796 or boceprevir, but both had a debilitating effect on the replicative capacity. These may be secondary changes that arose after other mutations had emerged and may not have such deleterious effects in that context. The interactions of these mutations with other changes remain to be investigated.

Although the development of HCV-796 was halted, a compound that is derived from this class of inhibitors but that lacks the hepatoxicity associated with HCV-796 may be clinically useful. Our replicon data suggest that the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir would provide increased antiviral efficacy compared to that of either agent alone; however, our ability to select a dually resistant replicon variant with the NS3 V170A and NS5B C316Y mutations suggests that viral variants with reduced susceptibility to both agents may arise under some treatment conditions. Our replicon cross-resistance studies suggest that dually resistant variants such as those with the NS3 V170A and NS5B C316Y mutations might also be selected if a mechanistically similar second-generation compound was substituted for HCV-796. However, the replicon variants selected in response to the combination of HCV-796 and boceprevir showed reduced fitness and remained sensitive to Peg-IFN. Taken together, these data provide a rationale for the clinical evaluation of a three-part combination of Peg-IFN, boceprevir, and a second-generation analog of HCV-796.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ellen Murphy for expert bioinformatics assistance and Jan Kieleczawa and Tony Li for sequencing support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appel, N., T. Schaller, F. Penin, and R. Bartenschlager. 2006. From structure to function: new insights into hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 281:9833-9836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blight, K. J., A. A. Kolykhalov, and C. M. Rice. 2000. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science 290:1972-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blight, K. J., J. A. McKeating, and C. M. Rice. 2002. Highly permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 76:13001-13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll, S. S., and D. B. Olsen. 2006. Nucleoside analog inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 6:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Francesco, R., and G. Migliaccio. 2005. Challenges and successes in developing new therapies for hepatitis C. Nature 436:953-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried, M. W., M. L. Shiffman, K. R. Reddy, C. Smith, G. Marinos, F. L. Goncales, Jr., D. Haussinger, M. Diago, G. Carosi, D. Dhumeaux, A. Craxi, A. Lin, J. Hoffman, and J. Yu. 2002. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:975-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godofsky, E. W., N. Afdhal, V. Rustgi, L. Shick, L. Duncan, X. L. Zhou, G. Chao, C. Fang, B. Fielman, M. Myers, and N. A. Brown. 2004. First clinical results for a novel antiviral treatment for hepatitis C: a phase I/II dose escalation trial assessing tolerance, pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity on NM283, a novel antiviral treatment for hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 126:A681. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gopalsamy, A., K. Lim, G. Ciszewski, K. Park, J. W. Ellingboe, J. Bloom, S. Insaf, J. Upeslacis, T. S. Mansour, G. Krishnamurthy, M. Damarla, Y. Pyatski, D. Ho, A. Y. Howe, M. Orlowski, B. Feld, and J. O'Connell. 2004. Discovery of pyrano[3,4-b]indoles as potent and selective HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 47:6603-6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammer, S. M., M. S. Saag, M. Schechter, J. S. Montaner, R. T. Schooley, D. M. Jacobsen, M. A. Thompson, C. C. Carpenter, M. A. Fischl, B. G. Gazzard, J. M. Gatell, M. S. Hirsch, D. A. Katzenstein, D. D. Richman, S. Vella, P. G. Yeni, and P. A. Volberding. 2006. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA panel. JAMA 296:827-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, Y., M. S. King, D. J. Kempf, L. Lu, H. B. Lim, P. Krishnan, W. Kati, T. Middleton, and A. Molla. 2008. Relative replication capacity and selective advantage profiles of protease inhibitor-resistant hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 protease mutants in the HCV genotype 1b replicon system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1101-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howe, A. Y., J. Bloom, C. J. Baldick, C. A. Benetatos, H. Cheng, J. S. Christensen, S. K. Chunduru, G. A. Coburn, B. Feld, A. Gopalsamy, W. P. Gorczyca, S. Herrmann, S. Johann, X. Jiang, M. L. Kimberland, G. Krisnamurthy, M. Olson, M. Orlowski, S. Swanberg, I. Thompson, M. Thorn, A. Del Vecchio, D. C. Young, M. van Zeijl, J. W. Ellingboe, J. Upeslacis, M. Collett, T. S. Mansour, and J. F. O'Connell. 2004. Novel nonnucleoside inhibitor of hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4813-4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howe, A. Y., H. Cheng, S. Johann, S. Mullen, S. K. Chunduru, D. C. Young, J. Bard, R. Chopra, G. Krishnamurthy, T. Mansour, and J. O'Connell. 2008. Molecular mechanism of hepatitis C virus replicon variants with reduced susceptibility to a benzofuran inhibitor, HCV-796. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3327-3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howe, A. Y., H. Cheng, I. Thompson, S. K. Chunduru, S. Herrmann, J. O'Connell, A. Agarwal, R. Chopra, and A. M. Del Vecchio. 2006. Molecular mechanism of a thumb domain hepatitis C virus nonnucleoside RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:4103-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howe, A. Y. M., R. Ralston, R. Chase, X. Tong, A. Skelton, M. Flint, S. Mullen, B. A. Malcolm, C. Broom, and E. Emini. 2007. Favorable cross-resistance profile of two novel hepatitis C virus inhibitors, SCH-503034 and HCV-796, and enhanced anti-replicon activity mediated by the combined use of both compounds. J. Hepatol. 46:S165. [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Howe, A. Y. M., et al. 2006. 13th Int. Meet. Hepatitis C Virus Related Viruses, abstr. 717.

- 15.Koch, U., and F. Narjes. 2006. Allosteric inhibition of the hepatitis C virus NS5B RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 6:31-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger, N., V. Lohmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 2001. Enhancement of hepatitis C virus RNA replication by cell culture-adaptive mutations. J. Virol. 75:4614-4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lahser, F. C., J. Wright-Minogue, A. Skelton, and B. A. Malcolm. 2003. Quantitative estimation of viral fitness using pyrosequencing. BioTechniques 34:26-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, C., C. A. Gates, B. G. Rao, D. L. Brennan, J. R. Fulghum, Y. P. Luong, J. D. Frantz, K. Lin, S. Ma, Y. Y. Wei, R. B. Perni, and A. D. Kwong. 2005. In vitro studies of cross-resistance mutations against two hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitors, VX-950 and BILN 2061. J. Biol. Chem. 280:36784-36791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, K., A. D. Kwong, and C. Lin. 2004. Combination of a hepatitis C virus NS3-NS4A protease inhibitor and alpha interferon synergistically inhibits viral RNA replication and facilitates viral RNA clearance in replicon cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4784-4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, K., R. B. Perni, A. D. Kwong, and C. Lin. 2006. VX-950, a novel hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3-4A protease inhibitor, exhibits potent antiviral activities in HCV replicon cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1813-1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindenbach, B. D., H. J. Thiel, and C. M. Rice. 2007. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 1101-1152. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA.

- 22.Lohmann, V., F. Korner, A. Dobierzewska, and R. Bartenschlager. 2001. Mutations in hepatitis C virus RNAs conferring cell culture adaptation. J. Virol. 75:1437-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu, L., T. J. Pilot-Matias, K. D. Stewart, J. T. Randolph, R. Pithawalla, W. He, P. P. Huang, L. L. Klein, H. Mo, and A. Molla. 2004. Mutations conferring resistance to a potent hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitor in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2260-2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manns, M. P., J. G. McHutchison, S. C. Gordon, V. K. Rustgi, M. Shiffman, R. Reindollar, Z. D. Goodman, K. Koury, M. Ling, and J. K. Albrecht. 2001. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 358:958-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCown, M. F., S. Rajyaguru, S. Le Pogam, S. Ali, W. R. Jiang, H. Kang, J. Symons, N. Cammack, and I. Najera. 2008. The hepatitis C virus replicon presents a higher barrier to resistance to nucleoside analogs than to nonnucleoside polymerase or protease inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1604-1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, M. E., J. E. Everhart, and J. H. Hoofnagle. 2006. Epidemiologic research and the action plan for liver disease research. Ann. Epidemiol. 16:861-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakagawa, S., T. Umehara, C. Matsuda, S. Kuge, M. Sudoh, and M. Kohara. 2007. Hsp90 inhibitors suppress HCV replication in replicon cells and humanized liver mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 353:882-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neumann, A. U., N. P. Lam, H. Dahari, D. R. Gretch, T. E. Wiley, T. J. Layden, and A. S. Perelson. 1998. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science 282:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nittoli, T., K. Curran, S. Insaf, M. DiGrandi, M. Orlowski, R. Chopra, A. Agarwal, A. Y. Howe, A. Prashad, M. B. Floyd, B. Johnson, A. Sutherland, K. Wheless, B. Feld, J. O'Connell, T. S. Mansour, and J. Bloom. 2007. Identification of anthranilic acid derivatives as a novel class of allosteric inhibitors of hepatitis C NS5B polymerase. J. Med. Chem. 50:2108-2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okamoto, T., Y. Nishimura, T. Ichimura, K. Suzuki, T. Miyamura, T. Suzuki, K. Moriishi, and Y. Matsuura. 2006. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by FKBP8 and Hsp90. EMBO J. 25:5015-5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reesink, H. W., S. Zeuzem, C. J. Weegink, N. Forestier, A. van Vliet, J. van de Wetering de Rooij, L. McNair, S. Purdy, R. Kauffman, J. Alam, and P. L. Jansen. 2006. Rapid decline of viral RNA in hepatitis C patients treated with VX-950: a phase Ib, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Gastroenterology 131:997-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichard, O., R. Schvarcz, and O. Weiland. 1997. Therapy of hepatitis C: alpha interferon and ribavirin. Hepatology 26:108S-111S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarrazin, C., R. Rouzier, F. Wagner, N. Forestier, D. Larrey, S. K. Gupta, M. Hussain, A. Shah, D. Cutler, J. Zhang, and S. Zeuzem. 2007. SCH 503034, a novel hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor, plus pegylated interferon alpha-2b for genotype 1 nonresponders. Gastroenterology 132:1270-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmonds, P., J. Bukh, C. Combet, G. Deleage, N. Enomoto, S. Feinstone, P. Halfon, G. Inchauspe, C. Kuiken, G. Maertens, M. Mizokami, D. G. Murphy, H. Okamoto, J. M. Pawlotsky, F. Penin, E. Sablon, I. T. Shin, L. J. Stuyver, H. J. Thiel, S. Viazov, A. J. Weiner, and A. Widell. 2005. Consensus proposals for a unified system of nomenclature of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 42:962-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong, X., R. Chase, A. Skelton, T. Chen, J. Wright-Minogue, and B. A. Malcolm. 2006. Identification and analysis of fitness of resistance mutations against the HCV protease inhibitor SCH 503034. Antivir. Res. 70:28-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villano, S., A. Howe, D. Raible, D. Harper, J. Speth, and G. Bichier. 2006. Analysis of HCV NS5B genetic variants following monotherapy with HCV-796, a non-nucleoside polymerase inhibitor, in treatment-naive HCV-infected patients. Hepatology 44:607A. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villano, S. A., D. Raible, D. Harper, J. Speth, P. Chandra, P. Shaw, and G. Bichier. 2007. Antiviral activity of the non-nucleoside polymerase inhibitor, HCV-796, in combination with pegylated interferon alfa-2b in treatment-naive patients with chronic HCV. J. Hepatol. 46:S24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasley, A., and M. J. Alter. 2000. Epidemiology of hepatitis C: geographic differences and temporal trends. Semin. Liver Dis. 20:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. 1997. Hepatitis C: global prevalence. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 72:341-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu, J. Z., N. Yao, M. Walker, and Z. Hong. 2005. Recent advances in discovery and development of promising therapeutics against hepatitis C virus NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 5:1103-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]