Abstract

DNAs harbored in both nuclei and mitochondria of eukaryotic cells are subject to continuous oxidative damage resulting from normal metabolic activities or environmental insults. Oxidative DNA damage is primarily reversed by the base excision repair (BER) pathway, initiated by N-glycosylase apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) lyase proteins. To execute an appropriate repair response, BER components must be distributed to accommodate levels of genotoxic stress that may vary considerably between nuclei and mitochondria, depending on the growth state and stress environment of the cell. Numerous examples exist where cells respond to signals, resulting in relocalization of proteins involved in key biological transactions. To address whether such dynamic localization contributes to efficient organelle-specific DNA repair, we determined the intracellular localization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae N-glycosylase/AP lyases, Ntg1 and Ntg2, in response to nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that Ntg1 is differentially localized to nuclei and mitochondria, likely in response to the oxidative DNA damage status of the organelle. Sumoylation is associated with targeting of Ntg1 to nuclei containing oxidative DNA damage. These studies demonstrate that trafficking of DNA repair proteins to organelles containing high levels of oxidative DNA damage may be a central point for regulating BER in response to oxidative stress.

Oxidative DNA damage, which occurs frequently in all cells, is linked to aging and human disease, such as cancer and various degenerative disorders (6, 13, 45, 81, 83). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a by-product of normal cellular metabolic processes that can cause oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins (79). Unrepaired oxidative DNA lesions can result in mutations and lead to arrest of both DNA replication and transcription (34). In order to combat such continuous insults to the genome, cells have evolved DNA repair and DNA damage tolerance pathways (2).

Base excision repair (BER) is the primary process by which oxidative DNA damage is repaired (74, 90). BER is initiated by the recognition and excision of a base lesion by an N-glycosylase, resulting in an apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site (47, 48). The resulting AP site is processed by an AP endonuclease or an AP lyase, which cleaves the sugar-phosphate DNA backbone on the 5′ side or 3′ side of the AP site, respectively (5). Subsequent processing involving DNA repair polymerases replaces the excised nucleotides, and DNA ligase completes the repair process (8).

Very little is known about how eukaryotic cells regulate events that initiate BER in response to oxidative stress. Deleterious oxidative DNA damage can occur in both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes, adding a level of complexity to this cellular response. In this case, the intracellular localization of BER proteins would be regulated dynamically in response to the introduction of either nuclear or mitochondrial DNA damage. Controlled protein localization has been implicated in the regulation of a number of critical cellular processes (24, 29, 37, 58). For example, under normal growth conditions the human c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase is cytoplasmic, but in response to cellular stress that results in DNA damage, c-Abl translocates into the nucleus, where it induces apoptosis (88). Yap1 is a critical transcription factor in the oxidative stress response in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) that is imported from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, where it regulates many stress response genes in response to oxidative stress (43). The human DJ-1 protein, mutations of which are implicated in Parkinson's disease (9), translocates to mitochondria following oxidative stress in order to protect against cytotoxicity (11, 46). Since subcellular localization is a regulatory component of numerous non-DNA repair pathways, it is possible that DNA repair is regulated in a similar manner.

If subcellular localization of BER proteins is regulated, then such events might be modulated through posttranslational modification. Phosphorylation, myristoylation, and numerous other modifications affect nuclear localization of certain proteins, such as c-Abl, FoxO proteins, and p53 proteins (10, 71, 88). Another posttranslational modification that has been implicated in modulation of intracellular localization, especially that of nuclear proteins, is modification by the ubiquitin-like protein SUMO (22, 30). Several proteins involved in DNA repair and maintenance are sumoylated, conferring a range of functions (55). For example, sumoylation of human thymine DNA glycosylase affects its glycosylase activity and localization to subnuclear regions (28, 54). SUMO modification also affects the nuclear localization of proteins such as mammalian heat shock transcription factor and the repressor of transcription, TEL, in response to environmental stress (27, 33, 42, 82). Sumoylated heat shock transcription factor colocalizes with nuclear stress granules, facilitating transcription of specific heat shock genes (33). SUMO modification of TEL is required for TEL export from the nucleus in response to cellular stresses, such as heat shock and exposure to UV radiation (27). Thus, SUMO modification is a major mechanism for regulation of subcellular protein localization.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been utilized extensively to investigate the mechanisms that underlie DNA repair, as the DNA damage management pathways are conserved between yeast and humans (18, 53). To determine whether targeting of BER proteins to the appropriate organelle harboring oxidative DNA damage is likely to represent a general regulatory component of DNA repair, we evaluated the localization of BER proteins in response to oxidative stress. This study focused on the S. cerevisiae BER proteins, Ntg1 and Ntg2, which are both homologs of Escherichia coli endonuclease III, possessing N-glycosylase/AP lyase activity that allows recognition and repair of oxidative base damage (primarily of pyrimidines) as well as abasic sites (3, 25, 73, 89). Because Ntg1 and Ntg2 play an important role in the repair of oxidative DNA damage in S. cerevisiae, the aim of this study was to determine how oxidative stress and sumoylation influence subcellular localization of these proteins. Consistent with the presence of predicted nuclear localization signals and a mitochondrial targeting sequence (4, 89), Ntg1 is found in both the nucleus and mitochondria (1, 90). In contrast, Ntg2, which contains only a putative nuclear localization signal but no mitochondrial targeting sequence, is localized exclusively to the nucleus (1, 90).

In this study, we evaluated the localization of Ntg1 and Ntg2 following exposure to nuclear and/or mitochondrial oxidative stress. The results show that the localization of Ntg1 is dynamically regulated in response to nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress. However, Ntg2 remains nuclear regardless of the oxidative stress state of the cell. Importantly, we provide evidence that dynamic localization of Ntg1 is a response to DNA damage rather than a general response to ROS. Additionally, sumoylation is associated with nuclear localization of Ntg1 that occurs in response to oxidative stress. These results indicate that the localization of BER proteins can likely be regulated by the introduction of nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage and suggest that sumoylation plays a role in modulating the localization of BER proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

Haploid S. cerevisiae strains and all plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Yeast cells were cultured at 30°C in rich YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, 0.005% adenine sulfate, and 2% agar for plates) or YPGal medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% galactose, 0.005% adenine sulfate, and 2% agar for plates). In order to introduce plasmids or integrated chromosomal gene modifications, yeast cells were transformed by a modified lithium acetate method (35).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description or genotype | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| FY86 (ACY193) | MATaura3-52 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 | 90 |

| ACY737 | MATaulp1ts ulp2Δ lys2 trp1 | 70 |

| SJR751 (DSC0025) | MATα ade2-101oc his3Δ200 ura3ΔNco lys2ΔBgl leu2-R | 75 |

| SJR1101 (DSC0051) | MATα ade2-101oc his3Δ200 ura3ΔNco lys2ΔBgl leu2-R ntg1Δ::LEU2 ntg2Δ::hisG apn1Δ::HIS3 rad1Δ::hisG | 75 |

| DSC0221 | MATaulp1ts ulp2Δ lys2 trp1 GAL-HA-SMT3 GAL-GST-NTG1 | This study |

| DSC0222 | MATaulp1ts ulp2Δ lys2 trp1 GAL-HA-SMT3 GAL-GST-NTG2 | This study |

| DSC0282 | MATaura3-52 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 ntg1::KAN bar1::HYG | This study |

| DSC0283 | MATaura3-52 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 ntg2::blasticidin bar1::HYG | This study |

| DSC0291 | MATaleu2Δ1 his3Δ200 ntg1::blasticidin bar1::HYG pNTG1-GFP [rho0] | This study |

| DSC0295 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met 15Δ0 ura3Δ0; TET-repressible C-terminally TAP-tagged Ntg1 | This study |

| DSC0296 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met 15Δ0 ura3Δ0; TET-repressible C-terminally TAP-tagged Ntg2 | This study |

| YSC1178-7499106 (DSC0297) | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0; C-terminally TAP-tagged Ntg1 | Open Biosystems |

| YSC1178-7502650 (DSC0298) | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0; C-terminally TAP-tagged Ntg2 | Open Biosystems |

| BY4147 (DSC0313) | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Open Biosystems |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNTG1-GFP | NTG1-GFP; 2μm URA3 Ampr | 41, 84, 90 |

| pNTG2-GFP | NTG2-GFP; 2μm URA3 Ampr | 41, 84, 90 |

| pNTG1K364R-GFP | NTG1 K364R-GFP; 2μm URA3 Ampr | This study |

| pFA-KMX4 | KanrCEN Ampr | 80 |

| pAG32 | Hygromycin B phosphotransferase MX4r Ampr | 23 |

| pCM225 | tet07CEN KanMX4 Ampr | 7 |

| p1375 | 3HA CEN TRP1 Ampr | 51 |

| p2245 | pGAL1-GST; CEN TRP1 Ampr | 51 |

The pPS904 green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression vector (2μm URA3) was employed for generation of C-terminally tagged Ntg1-GFP and Ntg2-GFP fusion proteins (41). The S. cerevisiae haploid strain FY86 was utilized for all localization studies (84). ΔNTG1 and ΔNTG2 strains (DSC0282 and DSC0283, respectively) were generated by precisely replacing the NTG1 and NTG2 open reading frames in FY86 with the kanamycin antibiotic resistance gene (pFA-KMX4 [80]; selected with 150 mg/liter G418 [U.S. Biologicals]) and blasticidin antibiotic resistance gene (BsdCassette vector pTEF1/Bsd 3.6 kb [Invitrogen]; selected with 100 mg/liter blasticidin S HCl [Invitrogen]), respectively. Plasmids encoding Ntg1-GFP or Ntg2-GFP were introduced into ΔNTG1 or ΔNTG2 cells. Plasmid mutagenesis of Ntg1-GFP to create Ntg1 K364R-GFP was performed using a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), and these plasmids were introduced into ΔNTG1 cells.

For studies of cells lacking mitochondrial DNA, a [rho0] yeast strain (DSC0291) was generated by incubating 4 × 106 ΔNTG1 cells in ethidium bromide as previously described (17). Following this incubation, cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Sigma) and MitoTracker Red CMXRos stain (Invitrogen) and evaluated via fluorescence microscopy in order to verify that no mitochondrial DNA was present.

Haploid yeast strains expressing integrated genomic copies of C-terminally tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tagged Ntg1 and Ntg2 were obtained from Open Biosystems (Ntg1-TAP [DSC0297] and Ntg2-TAP [DSC0298]). A tetracycline-repressible promoter (Tet off) from the plasmid pCM225 was integrated at the N termini of the NTG1 and NTG2 products by use of the kanamycin resistance gene to generate tetracycline-repressible Ntg1-TAP and tetracycline-repressible Ntg2-TAP strains (DSC0295 and DSC0296, respectively) as previously described (7). Cells expressing galactose-inducible Smt3-HA and Ntg1-GST (DSC0221) or Smt3-HA and Ntg2-GST (DSC0222) were generated by integrating the hemagglutinin (HA) tag from the vector p1375 and the GAL promoter and glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag from the vector p2245 (51) at the C termini of the SMT3 and NTG1 or NTG2 products in the haploid strain ACY737 (70). ACY737 contains mutations in the sumoylation-deconjugating enzymes, Ulp1 and Ulp2, which can aid in the isolation of sumoylated proteins (70).

Exposure to DNA damaging agents.

Cells were grown in 5 ml YPD to a density of 5 × 107 cells/ml, centrifuged, and washed with water. Cells were then resuspended in 5 ml water containing the appropriate DNA damaging agent, i.e., 2 to 20 mM H2O2 (Sigma), 25 to 55 mM methyl methanesulfonate (MMS; Sigma), or 10 μg/ml antimycin A (Sigma). Cells were exposed to an agent(s) for 1 hour at 30°C. Cytotoxicities of agents were evaluated by growing cells in agent, plating cells, and counting colonies.

Fluorescence microscopy.

For all experiments, cells (grown and treated as described above) were treated as follows: no treatment, 5 mM H2O2, 10 mM H2O2, 20 mM H2O2, 25 mM MMS, 55 mM MMS, 10 μg/ml antimycin, 5 mM H2O2 plus 10 μg/ml antimycin, 10 mM H2O2 plus 10 μg/ml antimycin, or 20 mM H2O2 plus 10 μg/ml antimycin. During exposure to DNA damaging agents, cultures were also incubated with 25 nM MitoTracker in order to visualize mitochondria. Following washes, cells were placed in 1 ml of water containing 1 μg DAPI to visualize DNA and then incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were washed and analyzed by direct fluorescence confocal microscopy, employing a Zeiss LSM510 Meta microscope. Images were analyzed using Carl Zeiss LSM image browser software, and cells were evaluated for nuclear only or nuclear plus mitochondrial Ntg1-GFP or Ntg2-GFP localization. Mitochondrion-only localization was negligible. At least 200 cells were counted for each strain and treatment condition, and each microscopic evaluation was repeated at least twice. Standard deviations were calculated for each strain and treatment condition. The image analysis software program Metamorph 6.2 was utilized in order to quantify the intensities of GFP in nuclei and mitochondria of individual cells. Mitochondrial GFP intensities were determined by subtracting nuclear GFP intensity from the total cellular GFP intensity. The fraction of cells with a mitochondrial GFP intensity score of >500 was determined for cells exposed to H2O2 and H2O2 plus antimycin, and the t test was employed to determine P values.

Measurement of ROS levels by flow cytometry.

For all experiments, cells were grown and treated as described above. Following exposure to DNA damaging agents, cells were washed with water and resuspended in YPD at a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml. Dihydroethidium (DHEt) was added to the YPD to a concentration of 160 μM to detect cellular superoxide (67), MitoSox (Molecular Probes) was added to the YPD to a concentration of 5 μM per the manufacturer's instructions to detect mitochondrial superoxide, or cells were left untreated. Cells were incubated for 45 min in the fluorescent dye, washed, and resuspended in 2 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The fluorescence intensity of 10,000 cells for each strain and condition was assessed by employing a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Excitation and emission wavelengths employed to evaluate cells were 488 nm and 595 nm, respectively, for DHEt and 488 nm and 575 nm, respectively, for MitoSox.

Ntg1 and Ntg2 analysis.

Purification of TAP-tagged Ntg1 and Ntg2 was achieved as follows. Four liters of tetracycline-repressible Ntg1-TAP (DSC0295) or Ntg2-TAP (DSC0296) was grown in YPD to a density of 5 × 107 cells/ml without tetracycline in order to overproduce Ntg1-TAP and Ntg2-TAP. Cells were then pelleted and washed with water. Cell pellets were frozen at −80°C. A version of the previously published TAP method was utilized (63), with the following modifications. Cell pellets were crushed with a mortar and pestle, and powdered yeast lysate was suspended in 10 ml buffer A (10 mM K-HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 mM benzamidine, 1 μM leupeptin, 2.6 μM aprotinin) with 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma) and 10 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma). Lysate was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, and supernatant was recentrifuged at 88,000 × g for 1 1/2 h. Dialysis, incubation with immunoglobulin G (IgG) beads, and incubation with tobacco etch virus (AcTEV; Invitrogen) protease were performed as instructed. Western analysis was performed on 50 μl of eluate. Anti-TAP antibody (1:3,333 dilution; Open Biosystems) was employed for Western analysis. Ntg2-TAP migrates as a slightly smaller species in Western analysis than the predicted TAP-tagged Ntg2 (∼53 kDa), while Ntg1-TAP migrates at its expected size of 55 kDa.

In order to purify GST-tagged Ntg1 and Ntg2, 1 liter of cells expressing galactose-inducible Smt3-HA and Ntg1-GST (DSC0221) or galactose-inducible Smt3-HA and Ntg2-GST (DSC0222) was grown in YPGal to a density of 5 × 107 cells/ml. Cells were centrifuged, and pellets were washed and frozen at −80°C. Cell pellets were crushed with a mortar, and powdered lysate was suspended in 500 μl PBS with 0.5 mM PMSF and 3 μg/ml (each) leupeptin and aprotinin. Lysate was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, and supernatant was applied to 150 μl washed glutathione-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (Amersham Biosciences). Beads and lysate were incubated at 4°C overnight. Beads were washed three times with 1 ml PBS, and then 50 μl of 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis loading buffer (50% [wt/vol] glycerol, 10% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% [vol/vol] 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.1% bromophenol blue) was applied to beads to elute the bound fraction. Western analysis was performed on 20 μl of eluate. Anti-HA (1:1,000 dilution; Covance) and anti-GST (1:1,000 dilution; Oncogene) antibodies were employed for immunoblotting.

Sucrose gradient subcellular fractionation.

In order to fractionate yeast cells into nuclear and mitochondrial preparations, 1 liter of cells expressing tetracycline-repressible Ntg1-TAP (DSC0295) or tetracycline-repressible Ntg2-TAP (DSC0296) was grown in YPD to a density of 5 × 107 cells/ml without tetracycline in order to overproduce Ntg1-TAP or Ntg2-TAP, respectively. Crude mitochondrial and nuclear protein lysate fractions were generated using a differential centrifugation protocol as described previously (14). Following this procedure, mitochondrial fractions were further purified using sucrose gradient centrifugation (61). Solutions of 20%, 40%, and 60% (wt/vol) sucrose in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF were prepared. The crude mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in the 20% sucrose solution. The 60% sucrose solution was placed in the bottom of a Beckman Ultraclear centrifuge tube, followed by the 40% sucrose solution and the 20% sucrose solution containing mitochondria. The tubes were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The mitochondria were removed from the 40%-60% interface, concentrated, resuspended in storage buffer (0.6 M sorbitol, 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 20% glycerol, 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 10 mM iodacetamide, 5 mg/ml aprotinin, 5 mg/ml leupeptin, and 0.1 M PMSF), and stored at −80°C.

The crude nuclear pellets were further purified using sucrose step gradient purification as previously described (66). The step gradient contained solutions of 58.2%, 68.8%, 71.9%, and 78.7% sucrose in sucrose buffer (8% polyvinylpyrrolidone 40, 11.5 mM KH2PO4, 8.4 mM K2HPO4, 0.75 mM MgCl2, pH 6.53). The nuclei were removed from the 71.9%-78.7% sucrose interface, concentrated, and resuspended in storage buffer. Western analysis was performed using 10 μg of nuclear or mitochondrial protein lysate. Anti-TAP, anti-Por1 (1:25,000 dilution; MitoSciences), and anti-Nop1 (1:25,000 dilution; EnCor) antibodies were employed for Western analysis. Anti-Nop1 and anti-Por1 antibodies were used to ensure enrichment of nuclear (Nop1) and mitochondrial (Por1) fractions (62). To optimize visualization, Western blot exposures were variable for each protein analyzed. Analysis of Western blots by chemiluminescence was employed in order to determine the change in sumoylated Ntg1 in the nuclear fraction. The ratio of modified to unmodified Ntg1 in the nuclear fraction was determined, and values for each condition were normalized to that for the no-treatment condition. The standard error of the mean was calculated for each strain and treatment condition, and the t test was employed to determine P values.

Functional analysis of Ntg1 in vivo.

To assess the function of Ntg1 in vivo, we utilized BER−/nucleotide excision repair-negative (NER−) (ntg1 ntg2 apn1 rad1) cells (SJR1101/DSC0051), which are highly sensitive to oxidative stress (75). BER−/NER− cells containing Ntg1-GFP or Ntg1 K364R-GFP plasmid were assessed for the ability of the episomal Ntg1 protein to function in vivo and decrease the sensitivity of these cells to treatment with H2O2. Cytotoxicity assays were carried out as described above for exposure to DNA damaging agents. The steady-state level of each GFP fusion protein was assessed by immunoblotting whole-cell lysates with a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:5,000 dilution) (72). Anti-phosphoglycerate kinase antibody (1:5,000 dilution; Invitrogen) was utilized to determine the relative levels of protein loaded per lane.

RESULTS

Ntg1 and Ntg2 localization under normal growth and oxygen conditions.

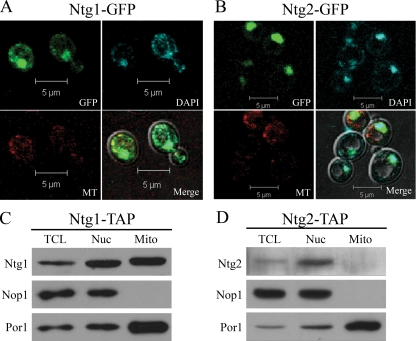

To determine whether changes in the subcellular distribution of Ntg1 and Ntg2 occur in response to oxidative stress-induced DNA damage, the localization of Ntg1-GFP and Ntg2-GFP was evaluated in live yeast cells. Under normal growth conditions, Ntg1 is localized to both nuclei and mitochondria, while Ntg2 localization is exclusively nuclear (1, 90). This localization pattern was verified by analyzing cells expressing either Ntg1-GFP or Ntg2-GFP by direct fluorescence microscopy. As expected, Ntg1-GFP was localized to both nuclei and mitochondria (Fig. 1A), whereas Ntg2-GFP localization was strictly nuclear (Fig. 1B). To biochemically confirm the organellar distribution of Ntg1 and Ntg2, sucrose gradient subcellular fractionation (see Materials and Methods) was performed on lysates from cells expressing Ntg1-TAP or Ntg2-TAP to separate nuclear and mitochondrial fractions. Nuclear and mitochondrial protein lysate fractions were evaluated for purity by use of antibodies against a nuclear protein, Nop1, and a mitochondrial membrane protein, Por1 (62). Mitochondrial fractions were free of nuclear proteins, as indicated by the detection of Por1 but not Nop1 (Fig. 1C and D). Nuclear fractions were enriched for nuclear proteins, with some mitochondrial contamination (Fig. 1C and D). These results were expected, as cytoplasmic contaminants have routinely been documented in conjunction with nuclear fractionation of S. cerevisiae (57, 65, 91). The localization of Ntg1-TAP and Ntg2-TAP was determined by probing nuclear and mitochondrial fractions. Sucrose gradient subcellular fractionation verified that Ntg1 was present in both nuclear and mitochondrial fractions (Fig. 1C), and Ntg2 was detected only in nuclear fractions (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Subcellular localization of Ntg1 and Ntg2 under normal growth conditions. (A and B) Localization of GFP-tagged proteins was assessed via direct fluorescence microscopy. GFP, DAPI, MitoTracker (MT), and merged images of cells expressing Ntg1-GFP or Ntg2-GFP are displayed. (C and D) Sucrose gradient subcellular fractionation (see Materials and Methods) and Western analysis were performed on Ntg1-TAP and Ntg2-TAP cells. Antibodies to Nop1 (nuclear marker protein), Por1 (mitochondrial marker protein), and the calmodulin domain of the TAP tag (to detect Ntg1 or Ntg2) were utilized to detect proteins present in total cell lysate (TCL), nuclear (Nuc), and mitochondrial (Mito) fractions.

Nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress induction by H2O2, antimycin, and MMS.

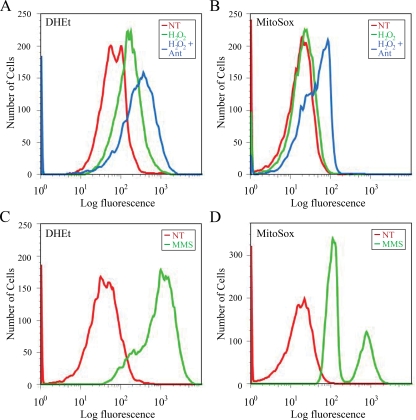

ROS levels increase in response to DNA damage in cells exposed to genotoxic agents, including MMS, UV light, and H2O2 (19, 67, 68). In order to determine whether increased ROS levels influence the localization of Ntg1 and Ntg2, wild-type cells were exposed to H2O2 to directly increase oxidative stress or to the DNA-alkylating agent MMS to indirectly increase ROS levels in response to DNA damage (68). In addition, cells were exposed to H2O2 plus antimycin to increase mitochondrial oxidative stress. Antimycin blocks oxidative phosphorylation (60), and exposure of cells to H2O2 plus antimycin increases oxidative stress, leading to induced oxidative DNA damage in yeast mitochondria (17). The relative levels of cellular ROS in different cellular compartments were determined following exposure to H2O2, H2O2 plus antimycin, and MMS by use of the fluorescent probes DHEt and MitoSox. DHEt is a general cellular superoxide probe (78), whereas MitoSox accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix, allowing determination of superoxide levels specifically in mitochondria (40). Analysis of cells by flow cytometry revealed that H2O2 exposure resulted in elevated levels of cellular superoxide compared to those in unexposed cells (Fig. 2A) but did not increase levels of mitochondrial superoxide (Fig. 2B). Flow cytometry analysis also revealed that H2O2 plus antimycin exposure resulted in a general cellular increase in superoxide levels, including an increase in mitochondrial superoxide, revealed by both the DHEt and MitoSox fluorescent probes (Fig. 2A and B). Exposure of cells to nonoxidative DNA damaging agents, such as MMS and UV light, can also increase cellular ROS levels (19, 67, 68). Consistent with this observation, exposure of cells to MMS resulted in a substantial elevation in both total cellular and mitochondrial superoxide levels compared to those in untreated controls (Fig. 2C and D). Evaluation of mitochondrial superoxide levels following treatment with MMS revealed two subpopulations of cells, each containing levels of mitochondrial superoxide higher than those observed with no treatment (Fig. 2D). These two subpopulations may represent cell stress and death response groups. Collectively, these results demonstrate that oxidative stress can be targeted to nuclei or mitochondria by exposure to specific agents. Importantly, a combination of H2O2 and antimycin or MMS exposure induces mitochondrial oxidative stress in a manner that is distinct from the primarily nuclear oxidative stress that results from exposure to H2O2 alone.

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of cells to determine intracellular ROS levels following nuclear or mitochondrial oxidative stress. (A and B) Cells were left untreated (NT) (red) or exposed to 20 mM H2O2 (green) or 20 mM H2O2 plus 10 μg/ml antimycin (blue) and incubated with DHEt or MitoSox to assess relative levels of total cellular superoxide (DHEt) or mitochondrial superoxide (MitoSox). (C and D) Cells were left untreated (red) or exposed to 55 mM MMS (green) and incubated with DHEt or MitoSox.

Relocalization of Ntg1 in response to increased nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress.

In order to assess whether the steady-state localization of Ntg1 is altered in response to nuclear oxidative stress, Ntg1-GFP localization was evaluated before and after a 1-hour induction of oxidative stress with various concentrations of H2O2 (Fig. 3A and B). The cytotoxicities for H2O2 exposures of 0 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM, and 20 mM were 0%, 64%, 68%, and 75%, respectively (data not shown). The localization of Ntg1-GFP was assessed by direct fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3B, Ntg1-GFP appeared more enriched in nuclei upon exposure to H2O2. In order to provide a quantitative measure of Ntg1-GFP localization, the subcellular localization of Ntg1-GFP was designated nuclear only or nuclear plus mitochondrial, based on colocalization with nuclear DAPI, mitochondrial DAPI, and MitoTracker staining in all cells displaying a GFP signal. The percentage of cells with nuclear only or nuclear plus mitochondrial localization of Ntg1-GFP was determined for several hundred cells for each treatment group. A dose-dependent increase in nuclear only Ntg1-GFP was observed following H2O2-induced nuclear oxidative stress (Fig. 3D). This result correlated with a dose-dependent decrease in the number of cells with a nuclear plus mitochondrial distribution of Ntg1-GFP, reflecting a decrease in mitochondrial localization of Ntg1. These results suggest that Ntg1 can be targeted to nuclei in response to nuclear oxidative stress.

FIG. 3.

Subcellular localization of Ntg1 following exposure to nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress. Localization of GFP-tagged Ntg1 was assessed via direct fluorescence microscopy following exposure to the indicated oxidative stress agent for 1 h. (A) GFP images of untreated cells expressing Ntg1-GFP. (B) GFP images of cells exposed to 20 mM H2O2. (C) GFP images of cells exposed to 20 mM H2O2 plus 10 μg/ml antimycin A. Arrows indicate increased mitochondrial Ntg1 localization observed by Metamorph image analysis. (D) Ntg1-GFP localization analysis. Cells were left untreated (NT) or were exposed to H2O2, MMS, and/or antimycin (Ant) as indicated (see Materials and Methods). Localization of Ntg1-GFP to nuclei only (nuclear) or nuclei plus mitochondria (nuc + mito) was determined for each cell and plotted as a percentage of the total cells evaluated. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Oxidative stress can be induced in mitochondria by exposing cells to H2O2 in combination with antimycin (Fig. 2B), resulting in increased mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage (17). We treated cells with H2O2 plus antimycin to determine whether elevated mitochondrial ROS trigger increased localization of Ntg1 to mitochondria. As shown in Fig. 3C, localization of Ntg1-GFP to mitochondria increased following H2O2-plus-antimycin-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress. The intensity of the GFP signal located in mitochondria of cells exposed to H2O2 plus antimycin was statistically greater than the intensity of the GFP signal located in mitochondria of H2O2-induced cells, as determined via image analysis using the software program Metamorph 6.2. Specifically, the fraction of cells containing a mitochondrial GFP intensity score of >500 was significantly greater for cells exposed to H2O2 plus antimycin (0.78 ± 0.08) than for cells exposed to H2O2 (0.63 ± 0.09) (P value = 0.04). These data indicate that Ntg1 localization is influenced by mitochondrial ROS. In addition to increased mitochondrial localization, Ntg1 nuclear localization was increased following exposure to low doses of H2O2 plus antimycin. H2O2 plus antimycin induces oxidative stress not only in mitochondria but also in nuclei, thus increasing Ntg1 nuclear localization as well (Fig. 2A and B).

Under normal growth conditions, Ntg2 is localized exclusively to nuclei (1, 90). Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether Ntg2 localization was affected by nuclear or mitochondrial oxidative stress. The localization of Ntg2-GFP was examined following exposure to nuclear (H2O2) or mitochondrial (H2O2 plus antimycin) oxidative stress. Ntg2-GFP localization remained exclusively nuclear following either nuclear or mitochondrial oxidative stress (data not shown), indicating that Ntg2 is not responsive to changes in either nuclear or mitochondrial oxidative stress.

Relocalization of Ntg1 in response to MMS exposure.

To determine whether other DNA damaging agents that do not directly cause oxidative DNA damage are also capable of inducing a change in the localization of Ntg1, cells were exposed to the DNA-alkylating agent MMS, resulting in an increase in intracellular ROS (68) (Fig. 2C and D). Survival of cells treated with 0 mM, 25 mM, and 55 mM MMS was 100%, 30%, and 3%, respectively (data not shown). An increase in nuclear only localization of Ntg1-GFP was observed following exposure to MMS (Fig. 3D) (P values of <0.04 for comparing nuclear only localization for no-treatment and MMS exposures). This result indicates that in addition to the ability of Ntg1 to respond to oxidative stress caused by H2O2 exposure, Ntg1 also responds to oxidative stress caused by DNA damaging agents, such as MMS, that do not directly introduce oxidative DNA damage.

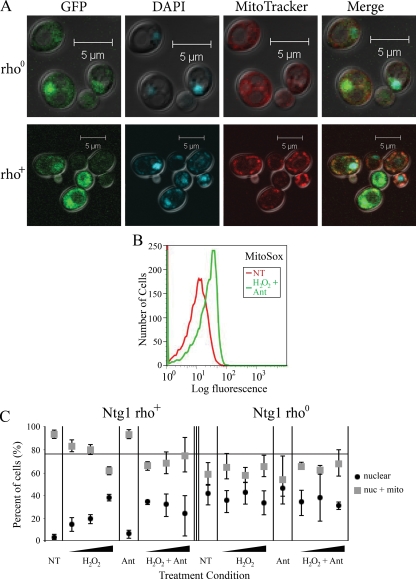

Oxidative stress-induced relocalization of Ntg1 to mitochondria is due to a DNA damage response.

Oxidative stress could provoke a change in localization of Ntg1 via a direct response to elevated levels of ROS or in response to the presence of oxidative DNA damage. In order to distinguish between these possibilities, [rho0] cells were generated as described in Materials and Methods. [rho0] mitochondria do not contain DNA, whereas [rho+] mitochondria contain intact DNA (20). The absence of mitochondrial DNA in [rho0] cells was confirmed by direct fluorescence microscopy, as evidenced by the absence of any extranuclear DAPI staining (Fig. 4A). In [rho0] cells, a lack of Ntg1 mitochondrial localization following increased mitochondrial oxidative stress (exposure to H2O2 plus antimycin) would indicate that Ntg1 responds to the presence of mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage rather than to ROS. Flow cytometric analysis of [rho0] cells revealed that mitochondrial superoxide levels increased in response to H2O2 plus antimycin exposure (Fig. 4B). Regardless of exposure to ROS-generating agents, fewer [rho0] mitochondria than [rho+] mitochondria contained Ntg1-GFP, as determined by colocalization of GFP with MitoTracker (Fig. 4A) and quantification of cells with nuclear or nuclear plus mitochondrial GFP-Ntg1 localization (Fig. 4C). The results indicate that [rho0] cells subjected to increasing levels of mitochondrial oxidative stress did not exhibit a change in Ntg1 localization (Fig. 4C). In contrast, [rho+] cells subjected to the same mitochondrial oxidative stress conditions displayed a significant increase in mitochondrial localization of Ntg1. Exposure of [rho+] cells to H2O2 plus antimycin results in increased mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage (17) caused by increased mitochondrial ROS (Fig. 2). The difference in Ntg1 localization observed between [rho0] and [rho+] cells indicates that mitochondrial oxidative stress induces DNA damage that results in the relocalization of Ntg1 to mitochondria. Importantly, these data suggest that the mitochondrial localization of Ntg1 is directed by the presence of mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage and not simply by elevated levels of mitochondrial ROS.

FIG. 4.

Mitochondrial localization of Ntg1 is influenced by mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage. [rho+] cells and [rho0] cells were analyzed in order to assess the change in localization of Ntg1-GFP in the presence and absence of mitochondrial DNA in response to mitochondrial oxidative stress. (A) Fluorescence microscopy was performed in order to confirm the [rho] status of the cells. Panels from left to right show GFP (Ntg1-GFP), DAPI (DNA), MitoTracker, and merged images. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of ROS levels in [rho0] cells. Cells were left untreated (NT) (red) or were exposed to 20 mM H2O2 plus 10 μg/ml antimycin (Ant) (green) and incubated with MitoSox to assess the levels of mitochondrial superoxide. (C) Quantification of Ntg1-GFP localization in [rho+] or [rho0] cells. Cells were left untreated (NT) or were exposed to H2O2 and/or antimycin (Ant) as indicated (see Materials and Methods). Localization of Ntg1-GFP to nuclei only (nuclear) or nuclei plus mitochondria (nuc + mito) was determined for each cell and plotted as a percentage of the total cells evaluated. Error bars represent standard deviations in the data. The gray line references an overall higher percent localization of Ntg1-GFP to mitochondria in [rho+] cells than in [rho0] cells (H2O2 plus antimycin).

Ntg1 and Ntg2 are posttranslationally modified by sumoylation.

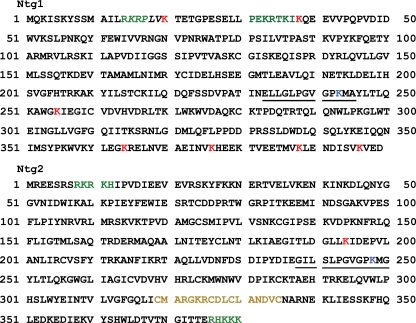

Posttranslational modification of various proteins via sumoylation can direct subcellular localization in response to environmental signals (27, 33, 42, 82). Several lines of evidence indicate that Ntg1 and Ntg2 may be modified posttranslationally by SUMO. Ntg1 and Ntg2 contain seven and one putative sumoylation site (Fig. 5), respectively, as predicted using the SUMO prediction program SUMOsp 1.0 (64, 85). Cell lysates from yeast that express Ntg1-GFP and Ntg2-GFP reveal a major species corresponding to the size of the fusion protein and a second, minor species of higher molecular size corresponding to the predicted size for monosumoylated Ntg1 and Ntg2 (90). In addition, a recent study cataloging sumoylated yeast proteins reported that Ntg1 interacts with the Smt3 gene (26), which encodes yeast SUMO (16, 39, 52); however, covalent modification of Ntg1 by Smt3 was not assessed in that study.

FIG. 5.

Amino acid sequences of Ntg1 and Ntg2. The amino acid sequences of Ntg1 (top) and Ntg2 (bottom) are shown. The following domain structures are indicated: potentially sumoylated lysines with a [hydrophobic]-K-X-[ED] motif (red) predicted by the SUMOsp 1.0 program (85), predicted nuclear localization sequences (green) determined with the NUCDISC subprogram of PSORTII (56), a predicted mitochondrial targeting sequence in Ntg1 (bold and italicized) determined with the MITDISC subprogram of PSORTII (56), predicted helix-hairpin-helix active-site regions (underlined) and active-site lysine (blue) determined due to significant homology with endonuclease III and its homologs (4, 31), and the [4Fe-2S] cluster (brown) characterized by the sequence C-X6-C-X-X-C-X5-C (44).

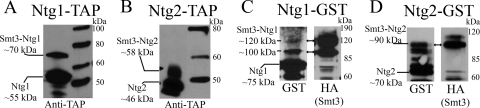

In order to test for sumoylation of Ntg1 and Ntg2, we looked for the presence of high-molecular-weight forms of Ntg1 and Ntg2. Western analysis of TAP-purified Ntg1 and Ntg2 revealed species corresponding to the sizes of Ntg1-TAP (55 kDa) and monosumoylated Ntg1-TAP (70 kDa) as well as Ntg2-TAP (46 kDa) and monosumoylated Ntg2 (58 kDa) (Fig. 6A and B). The sizes of the higher-molecular-size species correspond to the sizes predicted for addition of a single SUMO moiety (12 kDa) to both Ntg1 and Ntg2. To determine whether Smt3 is covalently attached to Ntg1 and Ntg2, GST-tagged Ntg1 and Ntg2 were purified from cells expressing both GST-tagged Ntg proteins and HA-tagged Smt3. Detection of the same high-molecular-weight species with both GST and HA antibodies would reveal covalent modification of Ntg1 and Ntg2. Western analysis confirmed the covalent modification of Ntg1 and Ntg2 by SUMO, as indicated by the codetection of a high-molecular-weight species by both GST and HA antibodies (Fig. 6C and D). Collectively, these results are consistent with the conclusion that both Ntg1 and Ntg2 are posttranslationally modified by sumoylation.

FIG. 6.

Posttranslational modification of Ntg1 and Ntg2 by SUMO. (A and B) Western analysis of TAP-purified Ntg1-TAP and Ntg2-TAP utilizing an anti-calmodulin TAP antibody. Nonsumoylated and sumoylated species of Ntg1 and Ntg2 are indicated. Protein sizes are indicated in the right margins. (C and D) Western analysis of purified Ntg1-GST and Ntg2-GST detected with antibodies to GST (Ntg1 or Ntg2) and HA (Smt3). Nonsumoylated and sumoylated species of Ntg1 and Ntg2 are indicated. Protein sizes are indicated in the right margin. Double-headed arrows indicate sumoylated Ntg1 and Ntg2 detected simultaneously with GST and HA antibodies.

Sumoylated Ntg1 accumulates in the nucleus following oxidative stress.

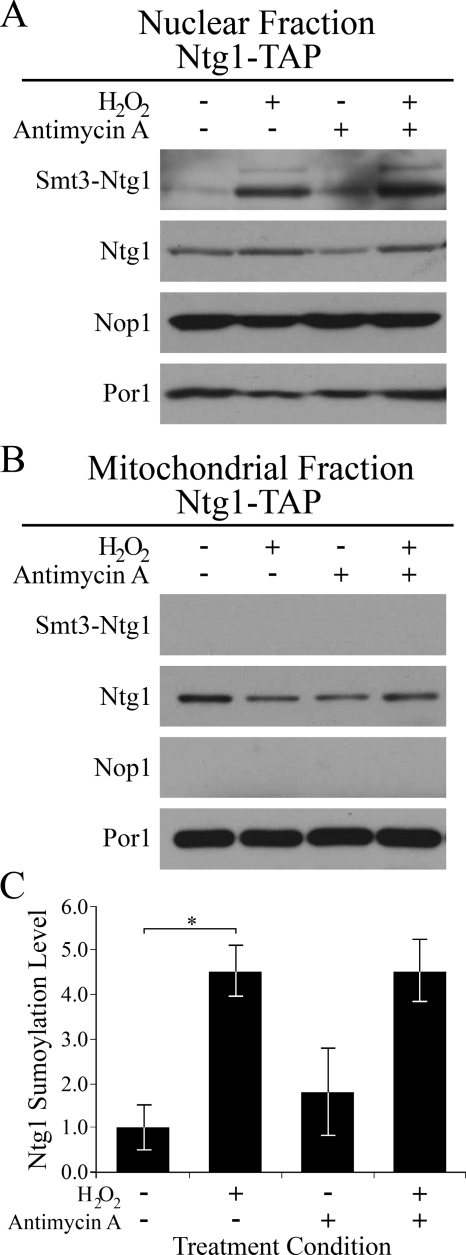

To address whether sumoylation could play a role in the subcellular localization of Ntg1, cells expressing TAP-tagged Ntg1 were exposed to H2O2 (nuclear oxidative stress) or H2O2 plus antimycin (mitochondrial oxidative stress) and subjected to sucrose gradient subcellular fractionation (see Materials and Methods). Mitochondrial fractions were free of nuclear proteins, as determined by Western analysis using Por1 and Nop1 as mitochondrial and nuclear protein markers (62), respectively, whereas nuclear fractions were enriched for nuclear proteins (Fig. 7A and B). Sumoylated Ntg1 was detected in nuclei and increased in amount relative to unmodified Ntg1-TAP following both nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress (Fig. 7A and B). Analysis of sumoylated and nonsumoylated Ntg1-TAP in nuclear fractions by chemiluminescence revealed that exposure to oxidative stress results in an approximately fivefold increase in nuclear sumoylated Ntg1 (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that sumoylation of Ntg1 is associated with the nuclear localization of Ntg1 in response to oxidative stress.

FIG. 7.

Sumoylation of nuclear Ntg1 increases in response to oxidative stress. Cells were exposed to no treatment, 10 mM H2O2, 10 μg/ml antimycin, or 10 mM H2O2 plus 10 μg/ml antimycin. Sucrose gradient subcellular fractionation (see Materials and Methods) was employed to assess the localization of Ntg1 to nuclei and mitochondria following exposure to nuclear (H2O2) or mitochondrial (H2O2 plus antimycin) stress-inducing agents. (A) Western analysis of nuclear fractions, utilizing antibodies to Nop1 (nuclear marker), Por1 (mitochondrial marker), and the calmodulin domain of TAP to detect Ntg1 and Smt3-Ntg1. (B) Western analysis of mitochondrial fractions. (C) Levels of nuclear sumoylated Ntg1 species detected by chemiluminescence in response to oxidative stress. Nucleus-enriched and mitochondrial subcellular fractions were generated (see Materials and Methods) and evaluated by Western analysis. Following chemiluminescence evaluation of nuclear Ntg1, unmodified and sumoylated Ntg1 proteins were quantified, and the change in percent sumoylated Ntg1 was calculated. Error bars represent standard errors of the means. The asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.005).

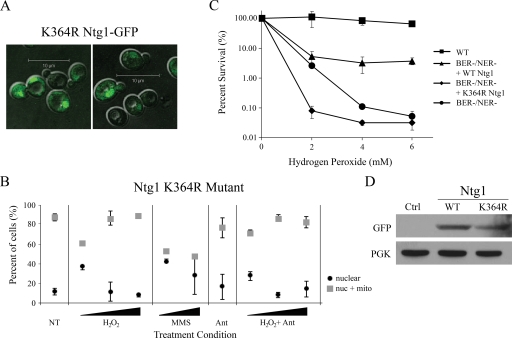

Subcellular localization and function of mutant Ntg1 lacking a predicted SUMO site.

The sumoylation prediction program SUMOsp 1.0 (85) was utilized to determine lysine residues where Ntg1 is most likely to be sumoylated. SUMOsp 1.0 predicted that lysine 364 within the sequence KREL was most likely to be sumoylated among the 36 lysines present in Ntg1. To assess the possible requirement for lysine 364 in Ntg1 function, lysine 364 was replaced with arginine. This amino acid substitution retains the positive charge of the residue but blocks sumoylation (32). In order to determine whether sumoylation could affect the subcellular distribution of Ntg1, the intracellular localization of Ntg1 K364R-GFP was compared to that of wild-type Ntg1-GFP. Ntg1 K364R-GFP was localized to both nuclei and mitochondria (Fig. 8A); however, the relocalization of Ntg1 K364R-GFP in response to H2O2 exposure (nuclear oxidative stress) or MMS exposure (Fig. 8B) was markedly different from that of wild-type Ntg1-GFP (Fig. 3). Specifically, the fraction of nuclear only Ntg1 K364R-GFP decreased in response to either H2O2 or MMS exposure, while the nuclear only localization of wild-type Ntg1-GFP increased in response to both agents (compare Fig. 3D and 8B). These results indicate that the predicted Ntg1 sumoylation site, K364, is important for relocalization of Ntg1 in response to nuclear oxidative stress, likely resulting in oxidative DNA damage, and provide further evidence of a role for SUMO in the dynamic localization of Ntg1.

FIG. 8.

Subcellular localization and function of the Ntg1 K364R mutant. (A) GFP image of cells expressing Ntg1 K364R-GFP. (B) Quantification of Ntg1 K364R-GFP localization. Cells were not treated (NT) or were exposed to the indicated oxidative stress-inducing agent for 1 h (see Materials and Methods). Localization of Ntg1 K364R-GFP to nuclei only (nuclear) or nuclei plus mitochondria (nuc + mito) was determined for each cell and plotted as a percentage of the total cells evaluated. Error bars represent standard deviations. Refer to Fig. 3D for localization of wild-type Ntg1. (C) Functional analysis of Ntg1 K364R. The H2O2 sensitivity of wild-type (WT) cells, BER−/NER− deficient cells, and BER−/NER− deficient cells containing an episomal copy of wild-type Ntg1-GFP or Ntg1 K364R-GFP was assessed. Cells were exposed to 0, 2, 4, or 6 mM H2O2. The percent survival was set to 100% for untreated samples. Error bars indicate standard deviations in the data. (D) Steady-state expression levels of wild-type Ntg1-GFP and mutant Ntg1 K364R-GFP in BER−/NER− deficient cells. Western analysis of whole-cell lysates from BER−/NER− deficient (ntg1 ntg2 apn1 rad1) cells (Ctrl) and BER−/NER− deficient cells containing an episomal copy of wild-type Ntg1-GFP (WT) or mutant Ntg1 K364R-GFP (K364R) was performed utilizing an anti-GFP antibody (to detect Ntg1) and anti-phosphoglycerate kinase antibody (to determine relative levels of protein loaded per lane).

In order to assess the function of Ntg1 K364R, which cannot properly relocalize in response to oxidative stress, we exploited BER−/NER− (ntg1 ntg2 apn1 rad1) defective cells (75). These BER−/NER− defective cells are severely compromised in the repair of oxidative DNA damage and are highly sensitive to H2O2 (75). Importantly, these cells lack endogenous Ntg1, so the function of Ntg1 K364R could be assessed as the only cellular copy of Ntg1. For this experiment, plasmids encoding wild-type Ntg1-GFP or Ntg1 K364R-GFP were transformed into BER−/NER− cells, and the sensitivity of these cells to H2O2 was determined (Fig. 8C). An episomal copy of wild-type Ntg1 substantially increased cell survival following H2O2 exposure compared to that of BER−/NER− cells. In contrast, following H2O2 treatment, the survival of BER−/NER− cells expressing Ntg1 K364R was comparable to or less than the survival of the control BER−/NER− cells, demonstrating that Ntg1 K364R is not properly localized in vivo to mediate its DNA repair function in the nucleus. To ensure that the compromised function of Ntg1 K364R was not due to decreased expression of the mutant protein, we assessed the steady-state levels of both Ntg1-GFP and Ntg1 K364R-GFP in cell lysates by immunoblotting with an anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 8D). This analysis revealed that the level of Ntg1 K364R was equivalent to that of wild-type Ntg1. These results suggest that the predicted Ntg1 sumoylation site, K364, is important for the function of Ntg1 in conferring cellular survival following oxidative stress.

DISCUSSION

To gain insight into the regulation of BER in response to oxidative stress-induced DNA damage, the localization and posttranslational modification of S. cerevisiae Ntg1 and Ntg2 were evaluated. We demonstrate that Ntg1 relocalizes in response to both nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage. In contrast, Ntg2 is exclusively nuclear, and this localization does not change in response to oxidative DNA damage. Furthermore, sumoylation of Ntg1 is associated with nuclear localization in response to nuclear oxidative stress.

ROS are a by-product of environmental factors and important cellular processes, including oxidative phosphorylation. Nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress occurs due to inefficiencies and malfunctions of these processes. Furthermore, increased nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress has been observed in cells with compromised nuclear and mitochondrial ROS scavenging systems (36, 50). Mitochondrial oxidative stress is increased when cellular oxidative phosphorylation activity is particularly high or disrupted (79). Furthermore, aging and various diseases have been associated with increased nuclear and mitochondrial ROS levels (13, 45, 81, 83). Under conditions where nuclear oxidative stress is high, nuclear oxidative DNA damage is elevated (19, 86). Likewise, conditions that increase mitochondrial oxidative stress are associated with high levels of mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage (17, 79). When oxidative stress is increased, it is essential for the cell to respond to oxidative DNA damage rapidly in order to prevent the detrimental consequences of unrepaired DNA, and a rapid response to oxidative DNA damage requires explicit regulation of BER components.

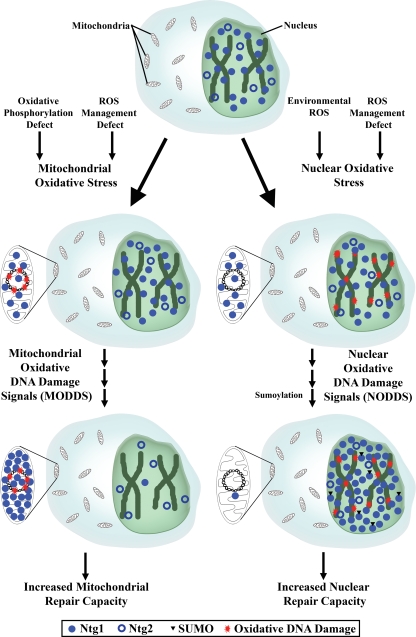

Regulating the localization of proteins is a way for cells to respond quickly to a stimulus without having to produce more protein. Because localization is a significant component of regulation for many processes (24, 29, 37, 58), we evaluated the localization of the BER proteins Ntg1 and Ntg2 in response to oxidative stress and determined that the localization of Ntg1 is influenced by nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress, whether the stress is caused by an oxidizing agent (H2O2) or indirectly by MMS, a nonoxidative DNA-alkylating agent (Fig. 3). In addition to Ntg1, the human transcription factor/AP endonuclease Ref1/hAPE was previously reported to translocate to nuclei and mitochondria following exposure to a DNA damaging agent (15, 21, 76, 77), adding further credibility to our claim that dynamic localization is a mechanism for regulation of BER in eukaryotic systems in general. In addition to demonstrating the dynamic localization of Ntg1, we were able to delineate the origin of the signal that results in targeting of Ntg1 to mitochondria by utilizing [rho0] yeast cells. Specifically, we demonstrated that Ntg1 responds to mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage and not simply to elevated levels of ROS (Fig. 4). To our knowledge, this is the first experimental strategy that has been able to distinguish between protein localization caused by ROS and its DNA damage products. We hypothesize that the nuclear localization of Ntg1 is similarly controlled by high levels of nuclear oxidative DNA damage. Because the localization of several human DNA repair proteins is affected by oxidative stress (15, 21, 49, 76, 77, 87, 88) and because BER is highly conserved between S. cerevisiae and humans, we suggest that modulation of DNA repair protein localization is a general mechanism by which BER is regulated in eukaryotic cells. We propose a model in which BER proteins such as Ntg1 are located in nuclei and mitochondria in cells under normal growth and oxygen conditions (Fig. 9). When nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress occurs, nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative DNA damages result. We hypothesize that specific signals are generated in response to oxidative DNA damage to target BER proteins such as Ntg1 to nuclei and mitochondria in order to increase the capacity to repair these lesions rapidly.

FIG. 9.

Proposed model for regulation of BER proteins in response to oxidative stress. The oxidative stress state of a cell is affected by its environment and metabolic processes. Nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage occurs as a result of nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative stress. Nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage initiates signaling of BER proteins, such as Ntg1, to sites of damage. NODDS and MODDS are responsible for recruiting BER proteins to nuclei and mitochondria, respectively. NODDS likely include the sumoylation machinery and influence nuclear protein localization. SUMO modification (triangles) of Ntg1 concentrates Ntg1 in the nucleus following oxidative stress. When the target BER proteins are contacted by NODDS or MODDS, relocalization to nuclei and/or mitochondria occurs, depending on the level of oxidative DNA damage present in each organelle. Following recruitment of BER proteins into the nucleus and mitochondria, the capacity for repair of oxidative DNA damage increases accordingly. In order to maintain a steady-state (baseline) level of BER proteins in nuclei, BER proteins such as Ntg2 do not relocalize in response to oxidative DNA damage.

Nuclear oxidative DNA damage signals (NODDS) and mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage signals (MODDS) are likely to involve various proteins and pathways, including components of the BER pathway, components of other DNA damage management pathways, and other molecules that are involved in cellular stress responses. Since oxidative DNA damage can be produced spontaneously, other types of spontaneous DNA damage, such as alkylation, methylation, deamination, and depurination, could alter the subcellular localization of BER proteins through signals similar to NODDS and MODDS. Our observation that Ntg1 relocalizes in response to MMS exposure supports the idea that a variety of spontaneous DNA damages can trigger recruitment of BER proteins. The signals from nonoxidative species of spontaneous DNA damage could recruit BER proteins directly or indirectly. Using alkylation as an example, abasic sites generated during repair of the alkylation damage may signal for recruitment of BER proteins directly, or the ROS produced as a result of the alkylation damage may cause oxidative DNA damage, which in turn recruits BER proteins through NODDS and MODDS.

We hypothesize that components of the sumoylation pathway are NODDS molecules. Several DNA repair and other DNA maintenance proteins are sumoylated (55), and sumoylation has been implicated in the nuclear localization of a number of proteins (59). Our results indicate that Ntg1 and Ntg2 are modified posttranslationally by sumoylation and are consistent with a model where sumoylation plays a role in the localization of Ntg1 to the nucleus in response to increased nuclear oxidative stress (Fig. 6 and 7). A fivefold increase in nuclear sumoylated Ntg1 was observed following oxidative stress. We found that 1% of the Ntg1 pool is sumoylated in cells under normal conditions, increasing to 5% in cells exposed to oxidative stress. These results are consistent with data describing other sumoylated proteins, where often less than 1% of the substrate can be detected as sumoylated at any given time (38). Sumoylation of a human BER N-glycosylase, thymine-DNA glycosylase, has been hypothesized to occur in a cyclical pattern of sumoylation and desumoylation (28, 38). In this case, sumoylated thymine-DNA glycosylase promotes a single event whose consequences persist after desumoylation (28). We hypothesize that sumoylation of Ntg1 occurs in order to concentrate Ntg1 within nuclei but that desumoylation occurs very quickly, making it very difficult to detect the pool of sumoylated Ntg1. Furthermore, we provide evidence that Ntg1 K364 is a potential target site of sumoylation that may contribute to the nuclear localization and function of Ntg1, although further experimentation is necessary to confirm this notion (Fig. 8). We predict that other nuclear BER proteins may be sumoylated in order to allow intricate regulation of DNA repair protein localization. The function of sumoylated Ntg2 is unknown, but it is possible that SUMO plays a role in modulating the intranuclear localization of Ntg2.

SUMO could contribute to the localization of BER proteins in several ways. Sumoylation of Ntg1 and other BER proteins could modulate interactions with nuclear transport receptors, as sumoylation modulates interaction with the nuclear transport receptors for various proteins (59). Sumoylation could also block BER proteins from exiting the nucleus in the event of oxidative DNA damage (Fig. 9). Sumoylation is also implicated in the regulation of subnuclear localization of numerous proteins. Localization of proteins to nucleoli, promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies, and other subnuclear locations is associated with sumoylation (22, 30). Therefore, sumoylation could allow Ntg1 and other BER proteins to accumulate in certain subnuclear, subgenomic regions containing oxidative DNA damage.

As Ntg1 localizes to both nuclei and mitochondria, the proportion of the pool of Ntg1 that localizes to each organelle must be adjusted so that some level of repair is maintained in nuclei and mitochondria at all times. Various factors are likely to influence the localization of Ntg1 to nuclei or mitochondria. Yeast mitochondrial DNA contains two to three times more oxidative lesions than nuclear DNA following oxidative stress induced by various agents (69). When more Ntg1 is needed in mitochondria, relocalization diminishes nuclear Ntg1 pools. Nuclear DNA will not accumulate significant DNA damage in the absence of Ntg1 because nuclear Ntg2, NER proteins, and Apn1 are available to repair baseline levels of oxidative DNA damage (75). Yeast mitochondria do not contain Ntg2 or NER proteins, leaving mitochondrial DNA vulnerable in the absence of Ntg1 (12). Because of the numerous factors influencing Ntg1 localization, a careful balance of NODDS and MODDS is required in order to increase repair capacity in one organelle without diminishing repair in the other. Such a balance of NODDS and MODDS is illustrated in [rho0] cells, as unexposed [rho0] cells display increased nuclear Ntg1 localization compared to unexposed [rho+] cells (Fig. 4C). We speculate that the increased nuclear localization results from elimination of MODDS-mediated recruitment of Ntg1 to mitochondria that results in enhanced recruitment of Ntg1 to nuclei by NODDS.

Very few investigations have addressed the issue of dynamic localization of BER proteins in the process of initiating BER in response to oxidative stress. Our studies have uncovered what is likely to be a major component of the regulation of BER. By controlling the subcellular localization of BER proteins, cells can rapidly mobilize repair machinery to sites of oxidative DNA damage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants ES 011163 (P.W.D.), GM 066355 (K.D.W.), GM0 58728 (A.H.C.), and GM008490 (training grant).

We thank the microscope core facility at the Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University School of Medicine, especially Katherine Hales and Adam Marcus. We thank the flow cytometry core facility at Emory University School of Medicine, especially Robert E. Karaffa II. We also thank the members of the Doetsch lab for helpful suggestions regarding the writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 November 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alseth, I., L. Eide, M. Pirovano, T. Rognes, E. Seeberg, and M. Bjoras. 1999. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologues of endonuclease III from Escherichia coli, Ntg1 and Ntg2, are both required for efficient repair of spontaneous and induced oxidative DNA damage in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 193779-3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., D. R. Walker, and E. V. Koonin. 1999. Conserved domains in DNA repair proteins and evolution of repair systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 271223-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augeri, L., K. K. Hamilton, A. M. Martin, P. Yohannes, and P. W. Doetsch. 1994. Purification and properties of yeast redoxyendonuclease. Methods Enzymol. 234102-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Augeri, L., Y. M. Lee, A. B. Barton, and P. W. Doetsch. 1997. Purification, characterization, gene cloning, and expression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae redoxyendonuclease, a homolog of Escherichia coli endonuclease III. Biochemistry 36721-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes, D. E., T. Lindahl, and B. Sedgwick. 1993. DNA repair. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5424-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckman, K. B., and B. N. Ames. 1997. Oxidative decay of DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 27219633-19636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belli, G., E. Gari, M. Aldea, and E. Herrero. 1998. Functional analysis of yeast essential genes using a promoter-substitution cassette and the tetracycline-regulatable dual expression system. Yeast 141127-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boiteux, S., and M. Guillet. 2004. Abasic sites in DNA: repair and biological consequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 31-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonifati, V., P. Rizzu, M. J. van Baren, O. Schaap, G. J. Breedveld, E. Krieger, M. C. J. Dekker, F. Squitieri, P. Ibanez, M. Joosse, J. W. van Dongen, N. Vanacore, J. C. van Swieten, A. Brice, G. Meco, C. M. van Duijn, B. A. Oostra, and P. Heutink. 2003. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science 299256-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calnan, D. R., and A. Brunet. 2008. The FoxO code. Oncogene 272276-2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canet-Avilés, R. M., M. A. Wilson, D. W. Miller, R. Ahmad, C. McLendon, S. Bandyopadhyay, M. J. Baptista, D. Ringe, G. A. Petsko, and M. R. Cookson. 2004. The Parkinson's disease protein DJ-1 is neuroprotective due to cysteine-sulfinic acid-driven mitochondrial localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1019103-9108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clayton, D. A., J. N. Doda, and E. C. Friedberg. 1974. The absence of a pyrimidine dimer repair mechanism in mammalian mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 712777-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooke, M. S., M. D. Evans, M. Dizdaroglu, and J. Lunec. 2003. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 171195-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diekert, K., A. I. de Kroon, G. Kispal, and R. Lill. 2001. Isolation and subfractionation of mitochondria from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Cell Biol. 6537-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding, S. Z., A. M. O'Hara, T. L. Denning, B. Dirden-Kramer, R. C. Mifflin, V. E. Reyes, K. A. Ryan, S. N. Elliott, T. Izumi, I. Boldogh, S. Mitra, P. B. Ernst, and S. E. Crowe. 2004. Helicobacter pylori and H2O2 increase AP endonuclease-1/redox factor-1 expression in human gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 127845-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohmen, R. J., R. Stappen, J. P. McGrath, H. Forrov, J. Kolarov, A. Goffeau, and A. Varshavsky. 1995. An essential yeast gene encoding a homolog of ubiquitin-activating enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 27018099-18109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doudican, N. A., B. Song, G. S. Shadel, and P. W. Doetsch. 2005. Oxidative DNA damage causes mitochondrial genomic instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 255196-5204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisen, J. A., and P. C. Hanawalt. 1999. A phylogenomic study of DNA repair genes, proteins, and processes. Mutat. Res. 435171-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evert, B. A., T. B. Salmon, B. Song, L. Jingjing, W. Siede, and P. W. Doetsch. 2004. Spontaneous DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae elicits phenotypic properties similar to cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27922585-22594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferguson, L. R., and R. C. von Borstel. 1992. Induction of the cytoplasmic ‘petite’ mutation by chemical and physical agents in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 265103-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frossi, B., G. Tell, P. Spessotto, A. Colombatti, G. Vitale, and C. Pucillo. 2002. H2O2 induces translocation of APE/Ref-1 to mitochondria in the Raji B-cell line. J. Cell Physiol. 193180-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill, G. 2004. SUMO and ubiquitin in the nucleus: different functions, similar mechanisms? Genes Dev. 182046-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker. 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 151541-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorlich, D. 1998. Transport into and out of the cell nucleus. EMBO J. 172721-2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna, M., B. L. Chow, N. J. Morey, S. Jinks-Robertson, P. W. Doetsch, and W. Xiao. 2004. Involvement of two endonuclease III homologs in the base excision repair pathway for the processing of DNA alkylation damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair 351-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannich, J. T., A. Lewis, M. B. Kroetz, S.-J. Li, H. Heide, A. Emili, and M. Hochstrasser. 2005. Defining the SUMO-modified proteome by multiple approaches in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2804102-4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanson, C. A., L. D. Wood, and S. W. Hiebert. 2008. Cellular stress triggers TEL nuclear export via two genetically separable pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 104488-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardeland, U., R. Steinacher, J. Jiricny, and P. Schar. 2002. Modification of the human thymine-DNA glycosylase by ubiquitin-like proteins facilitates enzymatic turnover. EMBO J. 211456-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartl, F.-U., N. Pfanner, D. W. Nicholson, and W. Neupert. 1989. Mitochondrial protein import. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Biomembr. 9881-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heun, P. 2007. SUMOrganization of the nucleus. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilbert, T. P., R. J. Boorstein, H. C. Kung, P. H. Bolton, D. Xing, R. P. Cunningham, and G. W. Teebor. 1996. Purification of a mammalian homologue of Escherichia coli endonuclease III: identification of a bovine pyrimidine hydrate-thymine glycol DNAse/AP lyase by irreversible cross linking to a thymine glycol-containing oligoxynucleotide. Biochemistry 352505-2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoege, C., B. Pfander, G.-L. Moldovan, G. Pyrowolakis, and S. Jentsch. 2002. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 419135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong, Y., R. Rogers, M. J. Matunis, C. N. Mayhew, M. Goodson, O.-K. Park-Sarge, and K. D. Sarge. 2001. Regulation of heat shock transcription factor 1 by stress-induced SUMO-1 modification. J. Biol. Chem. 27640263-40267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ide, H., Y. W. Kow, and S. S. Wallace. 1985. Thymine glycols and urea residues in M13 DNA constitute replicative blocks in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 138035-8052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata, and A. Kimura. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jamieson, D. J. 1998. Oxidative stress responses of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 141511-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jans, D. A., C. Xiao, and M. H. C. Lam. 2000. Nuclear targeting signal recognition: a key control point in nuclear transport? BioEssays 22532-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson, E. S. 2004. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73355-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson, E. S., I. Schwienhorst, R. J. Dohmen, and G. Blobel. 1997. The ubiquitin-like protein Smt3p is activated for conjugation to other proteins by an Aos1p/Uba2p heterodimer. EMBO J. 165509-5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson-Cadwell, L. I., M. B. Jekabsons, A. Wang, B. M. Polster, and D. G. Nicholls. 2007. ‘Mild uncoupling’ does not decrease mitochondrial superoxide levels in cultured cerebellar granule neurons but decreases spare respiratory capacity and increases toxicity to glutamate and oxidative stress. J. Neurochem. 1011619-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahana, J. A., B. J. Schnapp, and P. A. Silver. 1995. Kinetics of spindle pole body separation in budding yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 929707-9711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kono, K., Y. Harano, H. Hoshino, M. Kobayashi, D. P. Bazett-Jones, A. Muto, K. Igarashi, and S. Tashiro. 2008. The mobility of Bach2 nuclear foci is regulated by SUMO-1 modification. Exp. Cell Res. 314903-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuge, S., M. Arita, A. Murayama, K. Maeta, S. Izawa, Y. Inoue, and A. Nomoto. 2001. Regulation of the yeast Yap1p nuclear export signal is mediated by redox signal-induced reversible disulfide bond formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 216139-6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuo, C. F., D. E. McRee, C. L. Fisher, S. F. O'Handley, R. P. Cunningham, and J. A. Tainer. 1992. Atomic structure of the DNA repair [4Fe-4S] enzyme endonuclease III. Science 258434-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenaz, G. 1998. Role of mitochondria in oxidative stress and ageing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 136653-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, H. M., T. Niki, T. Taira, S. M. M. Iguchi-Ariga, and H. Ariga. 2005. Association of DJ-1 with chaperones and enhanced association and colocalization with mitochondrial Hsp70 by oxidative stress. Free Radic. Res. 391091-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindahl, T. 1979. DNA glycosylases, endonucleases for apurinic/apyrimidinic sites, and base excision-repair. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 22135-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindahl, T. 1976. New class of enzymes acting on damaged DNA. Nature 25964-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, W., A. F. Nichols, J. A. Graham, R. Dualan, A. Abbas, and S. Linn. 2000. Nuclear transport of human DDB protein induced by ultraviolet light. J. Biol. Chem. 27521429-21434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, X. F., I. Elashvili, E. B. Gralla, J. S. Valentine, P. Lapinskas, and V. C. Culotta. 1992. Yeast lacking superoxide dismutase. Isolation of genetic suppressors. J. Biol. Chem. 26718298-18302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meluh, P. B., and D. Koshland. 1995. Evidence that the MIF2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a centromere protein with homology to the mammalian centromere protein CENP-C. Mol. Biol. Cell 6793-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Memisoglu, A., and L. Samson. 2000. Base excision repair in yeast and mammals. Mutat. Res. 45139-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohan, R. D., A. Rao, J. Gagliardi, and M. Tini. 2007. SUMO-1-dependent allosteric regulation of thymine DNA glycosylase alters subnuclear localization and CBP/p300 recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27229-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muller, S., A. Ledl, and D. Schmidt. SUMO: a regulator of gene expression and genome integrity. Oncogene 231998-2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Nakai, K., and P. Horton. 1999. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2434-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nathanson, L., T. Xia, and M. P. Deutscher. 2003. Nuclear protein synthesis: a re-evaluation. RNA 99-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nigg, E. A. 1997. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: signals, mechanisms and regulation. Nature 386779-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palancade, B., and V. Doye. 2008. Sumoylating and desumoylating enzymes at nuclear pores: underpinning their unexpected duties? Trends Cell Biol. 18174-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Potter, V. R., and A. E. Reif. 1952. Inhibition of an electron transport component by antimycin A. J. Biol. Chem. 194287-297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Querol, A., and E. Barrio. 1990. A rapid and simple method for the preparation of yeast mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 181657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rieder, S. E., and S. D. Emr. 2001. Overview of subcellular fractionation procedures for the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2001unit 3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rigaut, G., A. Shevchenko, B. Rutz, M. Wilm, M. Mann, and B. Seraphin. 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 171030-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodriguez, M. S., C. Dargemont, and R. T. Hay. 2001. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 27612654-12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rout, M. P., and G. Blobel. 1993. Isolation of the yeast nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 123771-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rout, M. P., and J. V. Kilmartin. 1990. Components of the yeast spindle and spindle pole body. J. Cell Biol. 1111913-1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rowe, L. A., N. Degtyareva, and P. W. Doetsch. 2008. DNA damage-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 451167-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salmon, T. B., B. A. Evert, B. Song, and P. W. Doetsch. 2004. Biological consequences of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 323712-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santos, J. H., B. S. Mandavilli, and B. Van Houten. 2002. Measuring oxidative mtDNA damage and repair using quantitative PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 197159-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schwienhorst, I., E. S. Johnson, and R. J. Dohmen. 2000. SUMO conjugation and deconjugation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263771-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scoumanne, A., K. L. Harms, and X. Chen. 2005. Structural basis for gene activation by p53 family members. Cancer Biol. Ther. 41178-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seedorf, M., M. Damelin, J. Kahana, T. Taura, and P. A. Silver. 1999. Interactions between a nuclear transporter and a subset of nuclear pore complex proteins depend on Ran GTPase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 191547-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Senturker, S., P. Auffret van der Kemp, H. J. You, P. W. Doetsch, M. Dizdaroglu, and S. Boiteux. 1998. Substrate specificities of the Ntg1 and Ntg2 proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for oxidized DNA bases are not identical. Nucleic Acids Res. 265270-5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Slupphaug, G., B. Kavli, and H. E. Krokan. 2003. The interacting pathways for prevention and repair of oxidative DNA damage. Mutat. Res. 531231-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Swanson, R. L., N. J. Morey, P. W. Doetsch, and S. Jinks-Robertson. 1999. Overlapping specificities of base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, recombination, and translesion synthesis pathways for DNA base damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 192929-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tell, G., L. Pellizzari, C. Pucillo, F. Puglisi, D. Cesselli, M. R. Kelley, C. Di Loreto, and G. Damante. 2000. TSH controls Ref-1 nuclear translocation in thyroid cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 24383-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tell, G., A. Zecca, L. Pellizzari, P. Spessotto, A. Colombatti, M. R. Kelley, G. Damante, and C. Pucillo. 2000. An ‘environment to nucleus’ signaling system operates in B lymphocytes: redox status modulates BSAP/Pax-5 activation through Ref-1 nuclear translocation. Nucleic Acids Res. 281099-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trushina, E., R. B. Dyer, J. D. Badger, II, D. Ure, L. Eide, D. D. Tran, B. T. Vrieze, V. Legendre-Guillemin, P. S. McPherson, B. S. Mandavilli, B. Van Houten, S. Zeitlin, M. McNiven, R. Aebersold, M. Hayden, J. E. Parisi, E. Seeberg, I. Dragatsis, K. Doyle, A. Bender, C. Chacko, and C. T. McMurray. 2004. Mutant huntingtin impairs axonal trafficking in mammalian neurons in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 248195-8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Valentine, J. S., D. L. Wertz, T. J. Lyons, L. L. Liou, J. J. Goto, and E. B. Gralla. 1998. The dark side of dioxygen biochemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pöhlmann, and P. Philippsen. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 101793-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wallace, D. C. 1992. Diseases of the mitochondrial DNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 611175-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang, Y., I. Ladunga, A. R. Miller, K. M. Horken, T. Plucinak, D. P. Weeks, and C. P. Bailey. 2008. The small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) and SUMO-conjugating system of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics 179177-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wei, Y. H. 1998. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial DNA mutations in human aging. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 21753-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Winston, F., C. Dollard, and S. L. Ricupero-Hovasse. 1995. Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast 1153-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xue, Y., F. Zhou, C. Fu, Y. Xu, and X. Yao. 2006. SUMOsp: a web server for sumoylation site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 34W254-W257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yakes, F. M., and B. Van Houten. 1997. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94514-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoon, J. H., J. Qiu, S. Cai, Y. Chen, M. E. Cheetham, B. Shen, and G. P. Pfeifer. 2006. The retinitis pigmentosa-mutated RP2 protein exhibits exonuclease activity and translocates to the nucleus in response to DNA damage. Exp. Cell Res. 3121323-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yoshida, K., and Y. Miki. 2005. Enabling death by the Abl tyrosine kinase: mechanisms for nuclear shuttling of c-Abl in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle 4777-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.You, H. J., R. L. Swanson, and P. W. Doetsch. 1998. Saccharomyces cerevisiae possesses two functional homologues of Escherichia coli endonuclease III. Biochemistry 376033-6040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.You, H. J., R. L. Swanson, C. Harrington, A. H. Corbett, S. Jinks-Robertson, S. Senturker, S. S. Wallace, S. Boiteux, M. Dizdaroglu, and P. W. Doetsch. 1999. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ntg1p and Ntg2p: broad specificity N-glycosylases for the repair of oxidative DNA damage in the nucleus and mitochondria. Biochemistry 3811298-11306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zinser, E., and G. Daum. 1995. Isolation and biochemical characterization of organelles from the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 11493-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]