SYNOPSIS

Objective

The primary goal of this paper was to evaluate independent effects of stepfather parenting behaviors within the context of a parent training efficacy trial designed for recently married couples with children exhibiting behavior problems. A secondary goal was to examine measurement properties of a multiple-method, multiple-source construct of effective stepfathering including direct observation. Stepfather hypotheses were derived from a social interaction learning model of child adjustment and specifically evaluated the Oregon model of Parent Management Training (PMTO) intervention

Design

In a randomized control trial, 110 recently married families consisting of an early-elementary-school-aged focal child, biological mother, and stepfather were assessed over 2 years. Assessment included direct observation of stepfather - stepchild interactions. Analyses first tested intervention effects on change in stepfathering and second tested independent effects of stepfathering on change in children’s depression and noncompliance at follow-ups.

Results

The intervention produced medium effect sizes at 6 and 12 months for improved stepfathering with parenting effects diminishing at 24 months. Hierarchical regression models showed that intervention group improvements in stepfathering predicted greater reductions in children’s depression and noncompliance at 2 years relative to controls, controlling for change in mothering.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the preventive utility of the PMTO intervention for stepfathers. Implications for research, translation, timing of intervention, and implementation are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

In reviews of parenting effects on child and adolescent psychopathology, the proportion of studies including fathers has changed little over the past two decades (Phares & Compas, 1992; Phares, Fields, Kamboukos, & Lopez, 2005). In 2005, 45% of studies involved mothers only, 25% included mothers and fathers analyzed for maternal and paternal effects separately, 28% included both fathers and mothers but did not analyze them separately or did not specify parental gender. Two percent involved fathers only (Phares et al., 2005). We know even less about the direct and indirect effects of stepfathers (Amato & Sobolewski, 2004), not to mention studies evaluating the impact of stepfathering within the context of interventions. The focus of this report is to evaluate a theoretically driven parent training intervention to address the following questions: (1) Can intervention benefit stepfathers in a controlled randomized trial? (2) Do stepfathers produce independent effects on children’s developmental outcomes controlling for effects of mothers? (3) Do prior validated observation-based measures of parenting provide convergent validity and sensitivity to change for effective stepfathering in an experimental design?

Stepfamilies and Intervention

With shifts over the last three decades in divorce and subsequent repartnering, it is now estimated that one in three children the United States will live with a stepparent, the large majority being a stepfather (Amato & Sobolewski, 2004; Hofferth, Stueve, Pleck, Bianchi, & Sayer, 2002; Marsiglio, 2004). Although stepfamilies are becoming increasingly normative, appropriate parenting roles within these families tend to be poorly defined (Bray, 1999; Fine, Coleman, & Ganong, 1998; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). Studies that evaluate parenting practices in differing family structures often find decreasing childrearing effectiveness with each family structure transition, with two nondivorced biological parents being most effective (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 1999; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). It is becoming ever more imperative to identify intervention methods for mechanisms that can increase healthy development for children in stepfather families.

Finding ways to empower stepfathers without interfering with the biological mother’s function as care provider can be particularly challenging for intervention programs. Challenges include: differing family histories; children’s membership in two households; parent - child bonds are older compared to adult-spousal bonds; and potentially incongruent individual, marital, and family life cycles (Ganong & Coleman, 2004). Stepfamilies often have unrealistic expectations and can have difficulty clarifying roles and forming cohesive relationships, all factors that can increase distance between stepfathers and stepchildren. This distancing is particularly evident for stepfather parenting behaviors. Studies comparing step and biological fathers consistently find stepfathers more deficient in parenting both young and adolescent children. Stepfathers are less involved in discipline and monitoring (Fisher, Leve, O’Leary, & Leve, 2003; Hagan, Hollier, O’Connor, &: Eisenberg, 1992), exhibit low to moderate positive affect and low negative affect (Fine et al., 1998; Hetherington & Henderson, 1997), provide fewer directions to children (Vuchinich, Hetherington, Vuchinich, & Clingempeel, 1991), and employ less well-defined discipline practices (Bray, 1988). Interpersonal problem solving is also more conflicted in stepfamilies resulting in poorer problem-solving outcomes (Bray & Berger, 1993; Capaldi, Forgatch, & Crosby, 1994; DeGarmo & Forgatch, 1999). As a result of these distinctions, stepfathers have been characterized as “polite strangers” (Hetherington & Henderson, 1997) and as “playful spectators” (Patterson, 1982).

Given demographic trends it is surprising there are very few systematic evaluations of family interventions focused on parenting in stepfamilies (Lawton & Sanders, 1994). It is important to know if preventive interventions can promote positive, nurturing, and involved stepfathering that can enhance the healthy development of children. The Marriage And Parenting in Stepfamilies (MAPS) intervention program utilized the Oregon model of Parent Management Training (PMTO; Patterson, 2005).

PMTO is based on a social interaction learning model (SIL) in which parenting practices are hypothesized mechanisms predicting children’s adjustment outcomes (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992; Reid, Patterson, & Snyder, 2002). This clinical and preventive method has evolved over the course of 40 years for families with youngsters who have or are at risk for antisocial behavior and commonly co-occurring problems, such as depression and school failure. Risk factors for these youth include stressors within the social environment, such as family structure transitions, parental psychological or physical problems, poverty, trauma, and a wide range of adversities that challenge healthy family functioning. PMTO intervention emphasizes the influence of the social environment in shaping over-learned patterns of behavior that can generalize across social settings, for example, from home to school. When parents divorce (an important transition itself) and the custodial parent remarries (a second transition), parenting patterns often change and, of course, children have to adjust to the new family constellation. A PMTO efficacy trial focusing on divorced mothers demonstrated beneficial intervention effects on maternal parenting practices (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999). Improved parenting was subsequently shown to mediate long-term intervention effects on child outcomes of noncompliance, externalizing, delinquency, and internalizing behavior problems (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005; DeGarmo, Patterson, & Forgatch, 2004; Martinez & Forgatch, 2001).

In MAPS, remarriage was the risk variable for negative child outcomes because it is associated with disrupted parenting practices, the presumed mediators of developing externalizing and internalizing problems for children in stepfamilies. Stepparents bring with them histories and parenting practices that are unfamiliar to children and to their new partner. The couple may be happy with their own relationship, but their children may not be. Because both divorce and remarriage are risk factors associated with disrupted parenting, Forgatch and colleagues more tailored PMTO principles for single-mother families to the context of recently married stepfamilies (Forgatch, DeGarmo, & Beldavs, 2005). Unlike the group format for single-mothers, stepfamilies in MAPS received the intervention individually. The initial MAPS’ evaluation focused on couples’ coparenting and demonstrated improvements in combined parenting scores (Forgatch et al., 2005). It remains to be seen, however, whether measures focusing on stepfather behaviors demonstrate unique improvements or independent effects on child outcomes. To date, the MAPS study is one of two randomized controlled studies evaluating behavioral interventions for stepfamilies (Forgatch et al., 2005); the other was by Nicholson and Sanders (1999). We are aware of no studies that have examined independent effects of stepfathering in the context of a randomized control trial.

To address the above questions we examined psychometric properties of parenting scales based on observations of stepfather behaviors directed to the stepchild in structured family interaction tasks. We focused on observed stepfather - child interaction and paternal behaviors hypothesized to promote child adjustment. These behaviors are akin to paternal engagement: the direct interaction with the child in the form of caregiving, play, or leisure (Lamb, 1997; Pleck, 1997).

More specifically, the MAPS intervention was based on core parenting practices hypothesized to be controlling and reinforcing contingencies of child development (Patterson, 2005; Reid et el., 2002). A child’s interpersonal style and behavioral repertoire learned within the family is presumed to carry over to his or her interactions with peers and adults in other settings. In the absence of skilled parenting, a child may progress from a display of trivial aversive behaviors to aggressive behaviors inflicting harm on people or property. From the PMTO perspective, the parenting practices relevant for the prevention of behavior problems and those shown relevant for stepfamilies include effective monitoring and supervision, noncoercive discipline, skill encouragement, positive involvement, and effective problem solving (Bray, 1999; Kurdek, Fine, & Sinclair, 1995; Patterson, 2005).

Gender, Developmental Status, and Child Adjustment in Stepfamilies

A majority of children whose parents have divorced or remarried adapt well to changes in family structure (Hetherington, Bridges, & Insabella, 1998). However, children in newly remarried stepfamilies tend to demonstrate more adjustment problems than those in nondivorced, divorced, and one-parent households (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). Risks include poor psychological adjustment, behavior problems, academic problems, and greater substance use. Compared to nondivorced families, for example, representative data show that stepfamilies have higher levels of behavioral and emotional adjustment problems, three times greater need for psychological help, and 50% greater likelihood for repeating a grade (Zill, 1988). Children in stepfamilies also exhibit higher levels of noncompliance than children in nondivorced families (Vuchinich et al., 1991).

Prior evidence frequently reported divorce being more problematic for boys and remarriage for girls (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992), with boys increasing in conduct disorder and girls increasing in depression (Emery, 1982). In general, preadolescent boys are also significantly more likely to be identified as exhibiting behavioral problems than are girls (Anderson, Williams, McGee, & Silva, 1987). However, findings are mixed. Other reviews state that gender differences in response to divorce and remarriage are less consistent than previously thought, suggesting that increases in noncustodial and custodial father involvement following divorce may be more beneficial for boys, possibly vitiating previously noted gender differences (Amato & Keith, 1991; Hetherington et al., 1998).

Many studies report that adolescence is a risk period for children in stepfamilies (Hetherington et al., 1998; Hetherington, Stanley-Hagan, & Anderson, 1989). Father involvement and closeness with children in general declines during adolescence for father and stepfather relationships (Stewart, 2005), and shows that relative to biological father - son relationships, stepfather - stepson relationships decrease in positive interactions over time (Anderson & White, 1986; Bray, 1999; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). There is also evidence that nonresident father families (King, 2002) and stepfamilies show more problematic stepparent stepchild relations for girls (Amato & Keith, 1991; Coleman, Ganong, & Fine, 2000; Hetherington et al., 1998). These findings underscore the need for pre-adolescent prevention and adolescent intervention for both boys and girls.

Stepfather Hypotheses

Antisocial fathering has long been recognized as an influence on yountsters’ developmental outcomes (Dishion, Owen, & Bullock, 2004; Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, &: Taylor, 2003). For example, Patterson and Dishion (1988) showed that parental stressors and antisocial qualities for both mothers and fathers are associated with higher levels of irritable and explosive discipline practices. Relative to mothers, fathers’ inept discipline explained twice the variance in children’s problem behavior (Patterson et al., 1992). We expect coercive discipline behaviors that are problematic for biological fathers to be salient for stepfathers as well. The SIL model also specifies the significance of positive parenting practices (e.g., skill encouragement, monitoring, and problem solving skills) as a necessary context for promoting the development of prosocial behavior while effectively reducing coercive strategies (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2004).

Given risk of deficient parenting behaviors by stepfathers, we expected stepfathers with parent training to exhibit increases in effective parenting practices relative to stepfathers with no training. Improved stepfathering was expected to predict reductions in children’s problem behaviors in both externalizing (i.e., observed noncompliance to mothers) and internalizing problems (i.e., self-reported depression). Both child domains are salient outcomes during family structure transitions (DeGarmo et al., 2004). Noncompliance is a primary marker for the development of conduct disorder during divorce and remarriage (Forgatch et al 2005; Martinez & Forgatch, 2001) and is, therefore, a key criterion to evaluating the efficacy of a parent training intervention designed to prevent conduct disorder. We modeled noncompliance to mothers in stepfamilies as a criterion for two reasons. The first was because of low base-rate frequency in which fathers supply commands and directions (Patterson, 1982). This is particularly true for observational studies of noncompliance in step-families (Vuchinich et al., 1991). The second was because the MAPS PMTO curriculum focused on couples supporting each other in their parenting strategies to shape children’s behavioral contingencies. The stepfamily intervention literature recommends that the best approach for stepfathers in compliance issues is to support mothers in their directives to children (Visher & Visher, 1996). Further, we test whether stepfathers independently influence children’s behavior to the mother.

METHODS

Participants

Families were recruited from a metropolitan area in the Pacific Northwest through media advertisements (e.g., newspapers, radio spots, public flyers). Participants were 110 recently married couples that included a stepfather. Inclusion criteria required marriage within the prior 2 years and the focal child reside with the biological mother and be in Kindergarten through Grade 3. Children’s mean age at baseline was 7.47 (SD = 1.15). Seventy percent of children were boys. The sample was originally restricted to young boys who displayed early signs of conduct problems because they are more likely than girls to exhibit early externalizing after marital transitions. At midway study recruitment, girls were added to complete the recruitment schedule on time. Children were screened into the study for moderate levels of conduct problems with the goal of preventing the onset of conduct disorder. Boys had to have at least four externalizing behaviors and girls could have either four internalizing or externalizing behaviors on a checklist of 35 problem behaviors. These criteria were chosen because prior studies have shown that, in addition to acting out, girls are also susceptible to internalizing problems. The intervention curriculum was designed to focus on effective parenting practices expected to be relevant for both genders.

Couples had been married an average of 15.58 months (SD = 12.56), with mothers married an average of 2.06 times (SD = .79) and stepfathers 1.54 times (SD = .73). The mean number of children under 18 in the home was 2.22 (SD = 1.06). Most mothers and stepfathers had some education beyond high school (less than 2 years). Ten percent of the mothers and 11% of stepfathers had less than a high school education, and 36 and 32%, respectively, had completed high school with no further education. The average gross annual household income was $39,432 (SD = $21,537). The average age for mothers and stepfathers at baseline respectively was 31.3 and 32.7 (SD = 5.37, 6.60).

Theory-based Intervention and Design

Sixty-one percent of families were randomly assigned to the experimental condition and 39% to the control (i.e., randomization was set a priori at 6:4). Unequal group assignments provided better power to examine within group intervention processes (Vinokur, van Ryn, Gramlich, & Price, 1991). Prior to randomization, parents were told about the study and that participation in the intervention would be randomly determined. Because this was a prevention study in which families were not seeking assistance, families in the control condition received no intervention. If help was requested, however, families were given referral support. Families in both conditions were assessed on the same follow-up assessment timelines. Each participant was paid $10 an hour for assessments.

PMTO intervention operates by coaching parents to become the agents of change for their children because they are most proximal shaping agents with continuing involvement. Intervention content and procedures are described in Forgatch and Rains (1997), a manual that contains information for professionals and all necessary parent materials. The manual details 13 sessions in terms of agenda, objectives, rationales, sample dialogue, procedures, exercises, role-plays, and process suggestions. Parent materials include summaries of the session content, parenting principles, home practice assignments, charts, contracts, and other necessary supplies. Because the intervention is principle-based, and therefore rather flexible, interventionists are urged to pace the timing and application of the principles to fit each family’s needs. During development, expert stepfamily clinicians (Visher, 1994; Visher & Visher, 1996) offered consultation for adapting and enriching the PMTO program with strategies for managing stepfamily issues including: presenting a united parenting front, the role of stepparents, and debunking common stepfamily myths. For families electing to do so, we also offered marital-enhancement strategies based on marital research (Christensen, Jacobson, & Babcock, 1995) before initiating parent training components, although approximately one-fourth of the couples declined direct help with their relationship. For them, we redirected the communication and problem-solving skills training from couple issues to stepfamily issues. The parenting principles encompassed five core dimensions: skill encouragement, effective limit setting (e.g., discipline), monitoring, interpersonal problem solving, and positive involvement.

Program components and skills were provided in a progressive and integrated fashion. First, couples specified family expectations and goals and discussed stepfamily issues. Next, family strengths, couple communication skills, and couple problem-solving strategies were covered. Parents learned to provide effective directives, strategies to promote prosocial behavior with skillful teaching techniques, and contingent positive reinforcement. Next, parents learned noncorporal and noncoercive discipline strategies such as time out, work chores, and privilege removal, as well as the importance of balancing encouragement with limit setting at an approximate ratio of 5 positives to 1 negative. Communication and problem-solving skills for family meetings came next. Monitoring children in settings away from home, such as at school and with friends, was followed by positive involvement and reinforcement for school-related and other prosocial behavior. Finally, parents were helped to identify expected setbacks and challenges and strategize ways to manage them on their own.

The mean number of sessions attended was 11.71 (SD = 4.71). The average duration until termination was 27.42 weeks (SD = 16.15), more than twice as many weeks as sessions. Out of 67 intervention families, 56 attended at least one session. The analyses to follow were conducted as intent to treat analyses, the conservative standard for assessing randomized group effects regardless of intervention dosage or attendance.

There were one male and three female interventionists. Two had Masters and two had Doctorate degrees. Two had served as PMTO interventionists previously; the others had not conducted PMTO sessions before. They were trained and supervised in weekly meetings where videotapes of intervention sessions were viewed and role-plays were conducted. Evaluation of the interventionists’ competence and adherence to the method was evaluated with an observation-based measure of fidelity, the Fidelity of Implementation Code (FIMP: Knutson, Forgatch, & Rains, 2003). The FIMP measure is used to assess competent adherence to the intervention in terms of five dimensions: knowledge of the core parenting components, session and content structuring, skillful teaching (e.g., interactive as opposed to didactic), process skills (e.g., using sophistical clinical techniques such as support, joining), and successful application (e.g., adjusting procedures to family needs, apparent family satisfaction, making progress during the session) of principles and procedures. The FIMP measure was evaluated and demonstrated that higher levels of fidelity and adherence were associated with greater improvements in parenting within the experimental condition (Forgatch et al., 2005).

Measures

Extensive multiple-method data were obtained from questionnaires, interviews, and direct observation during four center visits, pre-intervention baseline, and three subsequent post-intervention follow-ups. Control group families were scheduled and assessed at center visits using the same assessment procedures as the intervention group. Assessors and observational coders were blind to which families were assigned to intervention and control groups. Although multiple sources of data were collected in the study, the stepfather parenting constructs in the present analyses were based solely on scored observations of videotaped interactions involving stepfathers and the focal child. For child outcomes, noncompliance was obtained from coded interactions involving the mother and the focal child, and child depression was obtained from an interviewer guided computerized questionnaire for children.

Observations of parent - child interactions were obtained during 7 structured family laboratory tasks: (1) refreshments (5 min – mother, child, stepfather), (2) problem solving – mother selected issue (7 min – mother and child only), (3) problem solving – child selected issue (7 min – mother, child, and stepfather), (4) family cooperation task (5 min – mother, child, and stepfather), (5) problem solving – couple selecting a parenting issue (7 min – mother, child, and stepfather), (6) problem solving – stepfather selected issue (5 min – stepfather and child only), and (7) a teaching task (10 min – mother and child only). Each of the laboratory tasks had been previously validated (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999) and was designed to elicit a range of prosocial or coercive parenting behaviors. The tasks structured opportunities for contingent encouragement, problem solving, monitoring, and positive involvement, or conversely coercive parenting (i.e., negative reciprocity, negative reinforcement, negative, and hostile engagement).

The refreshment task was a “warm up” in which families were asked to take a break from interviews and filling out questionnaires. Each of the problem solving discussions focused on current conflicts within the family selected from a checklist of common parent - child conflicts. They were asked to resolve issues rated as “hottest.” For the cooperation task, families were instructed to try and work together to make a structure from rubber building blocks as tall as possible. In the teaching task, mothers were asked to work with the child on a typical homework problem in which the materials were a grade level beyond the child’s current grade. In all, there were 48 min of videotaped interaction with 31 min of stepfather - child interaction.

Trained observers scored family interactions with the Family and Peer Process Code (FPP; Stubbs, Crosby, Forgatch, & Capaldi, 1998). FPP contains discrete positive, negative, and neutral behaviors scored in real-time and provides information on the initiator, recipient, sequence, content, affect, and duration. Following micro-social scoring using the FPP, coders rated global aspects of the interchanges (Forgatch, Mayne, & Knutson, 1998). Approximately 15% of interactions were randomly selected for blind reliability checks. Cohen’s Kappa, an indicator of coder agreement above chance, was .74 at baseline for content behaviors and .69 for affect for all of the FPP coded family interactions. Kappas were .63, .57, .66, and .64 over time specifically for stepfather negative codes initiated to the child used for computing coercive fathering indicators. Coders were also blind to random assignment so as not to introduce any coder biases in the efficacy evaluation.

Stepfathers’ Parenting Construct

Stepfather indicators were measures obtained from discrete micro-social behavior codes, Likert-type scales rated by coders, and Likert-type items rated by family interviewers. In selecting indicators for data reduction, we began with available micro-social and coder rated global parenting indicators that have shown clinical significance and predictive validity for fathers (Patterson, 1982; Patterson et al., 1992). These have included initiating negative engagement, negative reciprocity, and negative reinforcement. Global scales have included ratings of coercive discipline, positive involvement, problem-solving skills, and monitoring. The same validated parenting scores were obtained to control for mothering effects.

Positive involvement

This indicator was an 8-item scale rated for each of the interaction tasks in which the stepfather was involved. Items were rated on a 7-point scale and included ratings on warmth, empathy, encouragement, affection, and acceptance. Items were aggregated across tasks first and then combined as a scale score. Cronbach’s αs were .89, .88, .90, and .93 at baseline, 6,12, and 24 months, respectively.

Problem solving

This indicator was a 9-item scale scored from 7 min of interaction between stepfather and child attempting to resolve an issue selected by the stepfather. Items were rated on a 7-point scale and included items on solution quality, extent of resolution, apparent satisfaction, and likelihood of follow through (αs = .93, .96, .89, and .92 over time).

Monitoring and supervision

This indicator was a scale score from 3 parent-interviewer-rated items and 2 coder-rated items from the laboratory interaction tasks. Items were rated on a 5-point scale and evaluated supervision during the assessment and outside the laboratory (αs = .94, .85, .89, and .85). Sample items included: skillful in supervising, kept close track of youngster, knows what child is doing on a day-to-day basis, and allows antisocial behavior.

Coercive discipline

This indicator was a 12-item scale score rated on a 5-point scale; items included overly strict, authoritarian, erratic, and inconsistent (αs = .85, .88, .89, and .94 over time).

Negative reciprocity

This was a micro-social score derived from the Haberman binomial Z score (Gottman & Roy, 1990). The score depicts the conditional probability that the parent reciprocates a child’s aversive behavior with an aversive behavior.

Negative engagement

This indicator was a micro-social score computed as the proportion of negative behaviors a father initiated to a child divided by the total frequency of positives and negatives.

Negative reinforcement

This indicator was a micro-social score defined as the frequency of negative exchanges initiated by the stepfather and terminated by the child. Negative exchanges were the parental introduction of an aversive behavior preceded by at least 12 s of no aversive behavior, followed by an aversive behavior of the child within 12 s, followed by at least 12 s of no aversive behaviors.

Child Outcomes

Noncompliance

This discrete behavior score was the proportion of non-compliance computed as the total number of noncompliance divided by total compliance plus noncompliance given maternal directives observed during the interaction tasks.

Depression

This outcome was a construct score averaged from two child-reported indicators: depressed mood and loneliness and peer rejection. The first measure was reported by the child on the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985), a 27-item symptom-oriented summative index rated on a 3-point scale. Some items were reverse-scored so that all indicated increasing depression. Sample items were: feel sad, feel like crying, things bother you, feel alone, others love you (αs = .82, .76, .86, and .79, respectively). The second variable was measured with the Loneliness in Children Scale (LCS; Asher, Hymel, & Renshaw, 1984), a 16-item scale of loneliness and dissatisfaction with peer relations rated on a 3-point scale. Ten items were scored to indicate increasing loneliness. Sample items were: have nobody to talk to in class, lonely in school, don’t have any friends in school, feel left out (αs = .86, .81, .84, and .88).

Control variables

Sex of child was entered as 0 for boys and 1 for girls. Child age was measured in years of age since birth.

Attrition

As noted, the study design included four assessment periods: pre-intervention baseline, and 6, 12, and 24-month follow-ups. The participation rates were 91, 91, and 80 % at the respective follow-ups with no differential rates of attrition by intervention group assignment for any given follow-up. We also examined longitudinal patterns of missing data for each of the variables used in the analyses to follow. A missing-values analysis on the continuous level predictors and outcomes and categorical control variables indicated the data were missing completely at random (MCAR) over time, Little’s MCAR χ2 (67) was 58.14, p = .77, meaning there was no significant difference between estimated covariances among study variables for partial data families compared to complete data families. Furthermore, an attrition analyses indicated no significant differences on predictors or outcomes when comparing families retained and families not assessed at follow-up.

RESULTS

Analyses were conducted in three main steps including: (1) a factor analysis of stepfathering indicators, (2) an evaluation of intervention effects on changes in stepfathering using mean comparisons, and (3) an evaluation of stepfathering effects on children’s follow-up outcomes using hierarchical regression models.

Factor Analysis and Construct Score

A principal components factor analysis was conducted with varimax rotation of stepfathering indicators. Results of data reduction are presented in Table 1 with factor loadings lower than .30 suppressed. Single-factor solutions were extracted for each wave from baseline to 24 months with eigen-values greater than 2.0. The extracted factors explained 35 to 45% of the variance in effective parenting. Counter to expectations, micro-social indicators of negative reciprocity, and negative reinforcement did not load consistently as part of the core stepfathering construct over time. Negative reinforcement, central to coercion theory, did load at two of the four waves.

TABLE 1.

Principal Components Factor Analysis of Stepfather Indicators with Varimax Rotation1

| Parenting Indicator | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Involvement | .88 | .85 | .87 | .89 |

| Problem Solving - stepfather selected topic | .33 | .76 | .71 | .83 |

| Monitoring Construct | .76 | .59 | .68 | .71 |

| Coercive Discipline Scale | −.67 | −.80 | −.83 | −.80 |

| Negative Reciprocity | - | - | - | - |

| Negative Engagement (frequency proportion) | −.62 | −.63 | −.70 | −.68 |

| Negative Reinforcement (child terminate conflict) | −.35 | - | −.49 | - |

| Eigenvalue | 2.48 | 2.69 | 3.16 | 3.14 |

Note. Coefficients below .30 suppressed.

For all subsequent modeling, therefore, we computed a construct score based on the indicators demonstrating consistent factor structure over time, positive involvement, problem solving, monitoring, coercive discipline, and negative engagement. To examine change in the construct score over time, each continuous indicator was rescaled 0 to 1 before averaging. For example, the minimum and maximum ranges of any Likert-type rated indicator was rescaled 0 to 1 at each wave. For frequency counts of observed behaviors, scores were bounded by the minimum and maximum values across all waves. Therefore, the construct score was assessed on the same scale across time ranging from 0 to 1.

Intervention Effect Size on Stepfathering

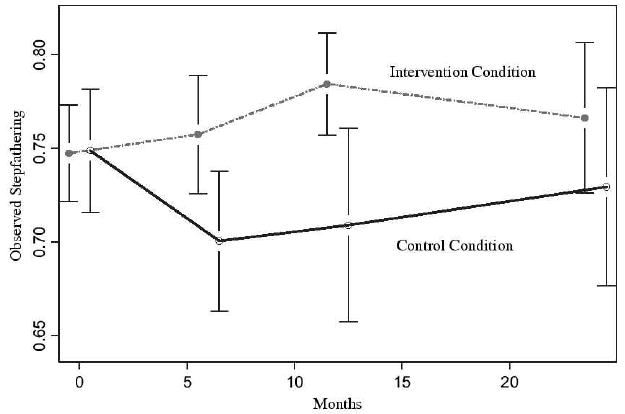

We next examined intervention impact on the stepfathering. Construct means and their 95th percent confidence intervals by group condition are plotted in Figure 1. Significant mean differences occur at any post-test follow-up period where a mean score for one group condition falls outside the confidence intervals of the other group condition. Significant intervention effects were obtained at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, M = .76, SD = .11, for intervention and M =.70, SD = .11, for controls, t = −2.28, p < .03 at 6 months; M = .78, SD = .10, and M = .71, SD = .15, t = −2.78, p<.01 at 12 months. No mean differences were found at 24 months, indicating 6- and 12-month intervention effects were not maintained at 2 years.

FIGURE 1.

Group by time means plot of effective stepfathering construct with 95% confidence intervals.

The 6- and 12-month effect sizes produced ds of .54 and .46, respectively. Cohen (1988) characterized d =.2 as small, d =.5 as medium, and d = .8 as large. Therefore, the intervention effect on stepfathering produced a medium effect size on improved stepfathering. We also explored intervention effects for the micro-social indicators that did not load in the above factor analyses. No intervention effects were found for negative reciprocity; however, small to medium effect sizes were obtained for negative reinforcement at 6 and 12 months.

Effects of Stepfathering on Developmental Outcomes

We next conducted a set of time-ordered hierarchical regressions to test effects of change in stepfathering. We entered early changes in stepfathering, those most proximal in time to the intervention, as predictors of long-term follow-up of children’s developmental outcomes. Entering time ordered effects provides greater theoretical confidence for causal inference by modeling lagged effects of the most proximal target of the intervention, presumed to change first (Singer & Willett, 2003). Supporting this specification, the prior PMTO efficacy trial for the single-mothers demonstrated that early changes in parenting within the first year that were most predictive of longer-term 3-year child outcomes (DeGarmo et al., 2004). Therefore, the criterion outcomes in this stepfamily report were modeled as change in child depression and noncompliance at the 12- and 24-month follow-ups, and stepfathering was entered as change from baseline to the 6-month follow-up assessment exhibiting the largest effect size.

Pre- and post-difference scores were computed as measures of change. Baseline (Time 1) was also entered to control for effects of initial status (see Kessler & Greenberg, 1981). Four blocks of variables were entered in the regressions. Model 1 included control variables, group assignment, entered as effects coding contrasts, scored “−1” for controls and “1” for intervention (Cohen & Cohen, 1983), and change in stepfathering. Model 1 stepfathering change represented effects of stepfathering for the whole sample. The change by group contrast entered in Model 2 represented intervention contrasts for the effect of stepfathering predicting child outcomes. Models 3 and 4 then entered change in mothering and change in mothering by group condition, respectively, to control for effects of mothering and to examine independent effects of stepfathering.

Results for the 12-month follow-up are shown in Table 2 in the form of standardized betas. Models 1 and 2 for change child depression and change in noncompliance did not demonstrate significant intervention group effects for stepfathering predicting child outcomes. However, there was a trend in the expected direction that approached significance for greater reductions in the experimental group relative to the controls, β = −.14, p <.08. Among the control variables, girls showed greater reduction in noncompliance relative to boys from baseline to 12 months. For assessing independent effects, change in mothering and fathering scores were strongly correlated, r =.57, p<.001, but were within tolerable ranges of colinearity for regression models.

TABLE 2.

Standardized Betas for 12 Month Change in Child Depression and Child Noncompliance regressed on Change in Stepfathering and Mothering by Intervention Group Contrasts

| 12 month Δ Child Depression |

12 month Δ Noncompiliance to Mother |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Intervention Group Contrast | −.05 | −.07 | −.07 | −.07 | .03 | .03 | .04 | .05 |

| Time 1 Child Outcome | −.68*** | −.66*** | −.66*** | −.66*** | −.73*** | −.74*** | −.73*** | −.73*** |

| Sex of Child | −.02 | −.01 | .00 | .00 | −.16* | −.16* | −.18* | −.18* |

| Age of Child | −.11 | −.12 | −.11 | −.11 | −.03 | −.03 | −.04 | −.04 |

| Time 1 Stepfathering | −.10 | −.07 | −.02 | −.02 | −.07 | −.09 | −.16 | −.17 |

| 6 Month Δ Stepfathering | −.02 | .01 | .05 | .05 | −.08 | −.10 | −.10 | −.08 |

| Group × Δ Stepfathering | - | −.14 | −.15 | −.15 | - | .09 | .09 | .03 |

| Time 1 Mothering | - | - | −.09 | −09 | - | - | .12 | .11 |

| 6 Month Δ Mothering | - | - | −.05 | −.06 | - | - | −.02 | −.05 |

| Group × Δ Mothering | - | - | - | .01 | - | - | - | .09 |

| Adjusted R2 | .44 | .44 | .43 | .42 | .54 | .54 | .54 | .54 |

Δ = Change;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Results for the 24-month follow-up are shown in Table 3. Hypotheses were supported for the 24-month follow-up. Model 2 showed a significantly greater effect of increases in effective stepfather predicting reductions in child depression in the intervention group relative to controls, β = −.17, p <.05. This effect remained significant controlling for changes in mothering. Similarly, models for noncompliance showed that early intervention effects on stepfather ing were associated with greater reductions in child noncompliance, independent of change in mothering, β = −.25, p <.01. Among the control variables, older children exhibited increases in noncompliance over time.

TABLE 3.

Standardized Betas for 24 Month Change in Child Depression and Child Noncompliance regressed on Change in Stepfathering and Mothering by Intervention Group Contrasts

| 24 month Δ Child Depression |

24 month Δ Noncompliance to Mother |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Intervention Group Contrast | −.01 | −.03 | −.03 | −.03 | .15 | .13 | .12 | .12 |

| Time 1 Child Outcome | −.70*** | −.68*** | −.67*** | −.67*** | −.69*** | −.68*** | −.69*** | −.69*** |

| Sex of Child | .02 | .03 | .05 | .05 | .01 | .02 | .04 | .04 |

| Age of Child | −.10 | −.11 | −.10 | −.10 | .16* | .15* | .16* | .16* |

| Time 1 Stepfathering | −.03 | −.01 | .04 | .04 | −.02 | .02 | .08 | .08 |

| 6 Month Δ Stepfathering | −.13 | −.10 | −.06 | −.04 | −.05 | −.02 | .01 | .02 |

| Group × Δ Stepfathering | - | −.17* | −.18* | −.23* | - | −.23** | −.24** | −.25** |

| Time 1 Mothering | - | - | −.09 | −.09 | - | - | −.11 | −.11 |

| 6 Month Δ Mothering | - | - | −.07 | −.09 | - | - | −.05 | −.06 |

| Group × Δ Mothering | - | - | - | .07 | - | - | - | .02 |

| Adjusted R2 | .47 | .49 | .49 | .49 | .50 | .55 | .54 | .55 |

Δ = Change;

p <.05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

In summary, the prediction models displayed a time-ordered pattern of intervention effects such that early improvements in stepfathering had beneficial impact on children’s developmental outcomes that appeared at 24 months. We note that non-significant effects for mothers stepped in the hierarchical regression subsequent to stepfathering effects did not mean that changes in mothering were not significantly associated with changes child outcomes. Rather, they were not independent of changes in stepfathering. In exploratory modeling not shown, mothering predicted child outcomes. This is consistent with the strongest effects for couples’ combined parenting scores in predicting child adjustment (Forgatch et al., 2005). Therefore, these findings imply that stepfathers played a unique role, independently and in conjunction with mother-driven improvements.

DISCUSSION

The present analyses addressed the question of whether stepfathers can provide independent effects on children’s adjustment outcomes within the context of a randomized efficacy trial. We first focused on factor analyses of several theoretically derived indicators of effective parenting. The goal was to examine factor convergence and sensitivity to change within a PMTO prevention study. We then tested the effects of changes in stepfathering on changes in child depression and child noncompliance over time. Stepfathering measures provided construct validity and criterion validity as an outcome, and more importantly, intervention effects on stepfathering were associated with decreases in children’s problem behaviors over time, with increasing effects at 2 years post baseline.

For the factor analyses, findings showed that key components of the social interaction learning model were extracted with consistency over time: coercive discipline, negative engagement, monitoring, problem solving, and positive involvement. The convergent factor was sensitive to the PMTO intervention in the efficacy analysis that followed. Counter to expectations, two observationally coded scores of discrete stepfather parenting behaviors did consistently not load over time as part of the core stepfathering construct. Negative reinforcement did load at two of the four assessment periods, and we noted that negative reinforcement demonstrated a small intervention effect benefiting families in the experimental condition. Further exploration is needed to understand why this theoretical indicator was unique relative to the main factor structure. We believe that more time sampling is needed to obtain a more reliable sequential score for stepfather - stepchild interactions (e.g., we only sampled 31 min). Additionally, because the MAPS design did not include a structured teaching task for stepfather and stepchild, we did not obtain an observational measure of skill encouragement. We also believe this is an essential dimension of fathering needing further evaluation.

In the second part of the analyses we found evidence of efficacy of the MAPS intervention on stepfathering detected at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. These effects produced medium effect sizes and were not detected at the 24-month follow-up. The group by time-mean plots showed that the intervention effect was maintained at higher levels; however, the control group eventually improved with time, consistent with prior studies. In terms of the less pronounced effect size at 2 years in stepfathering behaviors, we believe more research is needed to delineate mechanisms that contribute to the decline in this effect. It is likely that marital dynamics contribute to the differences in effect sizes over time for parenting measures as well as child adjustment outcomes (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Raymond, 2004).

The timing of effect sizes increasing to 1 year and then attenuating provides three possible implications. First, disruptions in effective family management for stepfathers and the difficulties in negotiating newly defined parenting roles following remarriage may be more problematic early on for stepfathers but may eventually be improved in the natural life-course of stepfamily formation following remarriage, as suggested in previous research (Hetherington & Henderson, 1997). Note that it is not so much decay in the parenting quality of the intervention stepfathers as it is increases (and larger variance) in the control group stepfathers that accounts for the loss of the effect. This would support Hetherington’s notion that, with time and before adolescence, stepfather families improve, at least in terms of stepfathers’ parenting. But the children whose stepfathers improved in parenting quality early on did better at 2 years compared with their control counterparts. If this is the case, it also suggests that effective parent training programs can accelerate the rate of adjustment to remarriage and prevent consequent negative developmental outcomes.

The findings for loss of parenting effects at 2 years suggest that booster sessions may be needed to maintain higher levels of effective parenting. The findings did provide evidence that early intervention after a transition was beneficial. More importantly, impacts on stepfathering were associated with beneficial reductions children’s outcomes at longer-term follow-up and probably longer. This finding is consistent with previous PMTO findings for single-mothers. In that study early intervention benefits to parenting had a positive impact on children’s outcomes 2 to 3 years later (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005). Most researchers agree that early intervention is best for child adjustment, but these findings also suggest that timing the intervention to take place as soon as possible after the marital transition may be effective for parenting as well.

Although the findings underscored the utility of parent training for stepfathers, there were several limitations to the current study. The study was conducted with a relatively small, homogeneous, and nonrepresentative sample. In two respects, however, it had some advantages; the sample was larger than almost all intervention studies of stepfamilies, and there were 2-year follow-up data. Multiple-method assessment was conducted at all times, and ITT analyses were conducted. The sample obtained medium effect sizes for changes in stepfathering behaviors. To our knowledge there is no another randomized controlled intervention study with follow-up data in stepfather samples. Unfortunately, the sample is potentially underpowered for examining unique moderating effects on, and effects of, developmental trajectories for boys versus girls.

The current analyses also focused on stepfathering. The stepfamily system also necessitates an understanding of the marital relationship over time. The model needs expanded to incorporate the role of the marital dynamics and potential moderating effects among parenting and the marital domain as predictors of child adjustment. Studies have also shown evidence that children’s behaviors affect the marital domain (Jenkins, Simpson, Dunn, Rasbash, & O’Connor, 2005) and that stepparent-stepchild relationships are generally the strongest predictor of marital quality (Pasley, Ihinger-Tallman, & Lofquist, 1994). The role of involvement by the biological father is also omitted and potentially important for the stepfamily couple as well as child adjustment (MacDonald & DeMaris, 2002). Such analyses are beyond the scope of the current paper but need further attention (see Cummings et al., 2004).

In spite of limitations, the current findings have important implications. They underscore that stepfather parenting practices are malleable to intervention, and that such improvements can have unique effects on children’s developmental outcomes. Such efforts can inform intervention development for other father populations including divorced fathers, non-residential fathers, and incarcerated fathers. For many fathering initiatives, it is rare that developmental outcomes of children are included and many rely on single sources of data (Parke, Dennis, Flyr, Morris, Killian, McDowell, & Wild, 2004). We believe there is a great need for more specified work and replication work on factors associated with determinants of effective fathering using intervention technologies and randomized trials for other nontraditional fathers. Very few systematic or randomized control trials have been conducted based on theoretically supported interventions regarding fathering behaviors (McBride & Lutz, 2004).

Another area needing attention regards aspects of fathering identity, commitment, and role taking that are unique compared to mothers. These factors have been hypothesized to be moderators of involvement but their role in direct relation to parenting practices is less understood. In addition to further translation work, we need to know if implementation is feasible in community settings. Currently, implementation of PMTO within community agencies is being assessed in a national level in Norway (see Ogden, Forgatch, Askeland, Patterson, & Bullock, 2005) and statewide in Michigan (see Hodges, Forgatch, & Wotring, in press). Do efficacious programs replicate and can their effectiveness be sustained at the community level?

Given current demographic trends that are not likely to reverse, non-traditional family structures are becoming the norm. This makes it even more imperative to identify malleable mechanisms and intervention methods that can increase healthy development for children in these families. We must test ways to empower stepfathers without interfering with the biological mother’s function as care provider. The present study demonstrated the beneficial utility of the PMTO model for stepfathers.

Acknowledgments

Research directly reported in this paper was supported by grant RO1 MH 54703 Child and Adolescent Treatment and Preventive Intervention, Research Branch, DSIR, NIMH. Support was also provided in part by RO1 HD 42115, Demographic and Behavioral Sciences Branch, NICHD and P20 DA 017592 funded by the NIDA. Authors would also like to thank Kelly Bryson for editorial assistance, and the intervention and coding teams at the Oregon Social Learning Center.

References

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Sobolewski JM. The effects of divorce on fathers and children: Non-residential fathers and stepfathers. In: Lamb M, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JZ, White GD. An empirical investigation of interaction and relationship patterns in functional and dysfunctional nuclear families and stepfamilies. Family Process. 1986;25:407–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1986.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Williams SM, McGee, Silva RS. DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children: Prevalence in a large sample from the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44(1):69–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800130081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Hymel S, Renshaw PD. Loneliness in children. Child Development. 1984;55:1456–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH. Children’s development during early remarriage. In: Hetherington EM, Arasteh JD, editors. Impact of Divorce, Single Parenting, and Stepparenting on Children. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH. From marriage to remarriage and beyond: Findings from the Developmental Issues in StepFamilies Project. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage: A risk and resiliency perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH, Berger SH. Developmental issues in StepFamilies Research Project: Family relationships and parent–child interactions. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;7(1):76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Forgatch MS, Crosby L. Affective expression in family problem-solving discussions with adolescent boys. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1994;9(1):28–49. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Jacobson NS, Babcock JC. Integrative behavioral couple therapy. In: Jacoboson NS, Gurman AS, editors. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy. New York: Guilford; 1995. pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Social Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong L, Fine M. Reinvestigating remarriage: Another decade of progress. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1288–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Raymond J. The Role of the Father in Child Development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict; pp. 196–221. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Contexts as predictors of changing parenting practices in diverse family structures: A social interactional perspective to risk and resilience. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping with Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage: A Risk and Resiliency Perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 227–252. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Putting problem solving to the test: Replicating experimental interventions for preventing youngsters’ problem behaviors. In: Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, editors. Continuity and Change in Family Relations: Theory, Methods, and Empirical Findings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 267–290. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Early development of delinquency within divorced families: Evaluating a randomized preventive intervention trial. Developmental Science. 2005;8(3):229–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. How do outcomes in a specified parent training intervention maintain or wane over time? Prevention Science. 2004;5(2):73–89. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000023078.30191.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Owen LD, Bullock BM. Like father, like son: Toward a developmental model for the transmission of male deviance across generations. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2004;1(2):105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. Interparental conflict and the children of discord and divorce. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92:310–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine MA, Coleman M, Ganong LH. Consistency in perceptions of the step-parent role among step-parents, parents and stepchildren. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15(6):810–828. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Leve LD, O’Leary CC, Leve C. Parental monitoring of children’s behavior: Variation across stepmother, stepfather, and two-parent biological families. Family Relations. 2003;52:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single-mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:711–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS, Beldavs Z. An efficacious theory-based intervention for stepfamilies. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:357–365. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Mayne T, Knutson NM. MAIS FPP Coder Impressions: Center Assessment Families (CAF) Eugene, OR: 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity; Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training (PMTO) Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Rains L. MAPS: Marriage and Parenting in Stepfamilies, Parent Training Manual. Eugene, OR: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ganong L, Coleman M. Stepfaniily Relationships: Development, Dynamics, and Intervention. New York, NY: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Roy AK. Sequential analysis: A Guide for Behavioral Researchers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan MS, Hollier EA, O’Connor TG, Eisenberg M. Parent-child relationships in nondivorced, divorced single-mother, and remarried families. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3):94–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Bridges M, Insabella GM. What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children’s adjustment. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):167–184. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3):1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Henderson SH. Fathers in stepfamilies. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 212–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Stanley-Hagan M, Anderson ER. Marital transitions: A child’s perspective. American Psychologist. 1989;44(2):303–312. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges K, Forgatch MS, Wotring J. A performance measurement system facilitates implementation of EBTs: A case study with PMTO. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL, Stueve JL, Pleck J, Bianchi S, Sayer L. The demography of fathers: What fathers do. In: Tamis-LeMonda CS, Cabrera N, editors. Handbook of Father Involvement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A. Life with (or without) father: The benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father’s antisocial behavior. Child Development. 2003;74(1):109–126. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J, Simpson A, Dunn J, Rasbash J, O’Connor TG. Mutual influence of marital conflict and children’s behavior problems: Shared and nonshared family risks. Child Development. 2005;76(1):24–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Greenberg DF. Linear panel analysis: Models of quantitative change. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- King V. Parental divorce and interpersonal trust in adult offspring. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;66:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson NM, Forgatch MS, Rains LA. Fidelity of Implementation Code Revised (coding manual) Eugene, OR: Oregon Social Learning Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression, Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21(4):995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA, Fine MA, Sinclair RJ. School adjustment in sixth graders: Parenting transitions, family climate, and peer norm effects. Child Development. 1995;66:430–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M. Fathers and child development: An introductory overview and guide. In: Lamb M, editor. The Role of Fathers in Child Development. Third. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton JM, Sanders MR. Designing effective behavioral family interventions for stepfamilies. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14(5):463–496. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald WL, DeMaris A. Stepfather - stepchild relationship quality: The stepfatiler’s demand for conformity and the biological father’s involvement. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23(1):121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W. Stepdads: Stories of Love, Hope, and Repair. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Jr, Forgatch MS. Preventing problems with boys’ noncompliance: Effects of a parent training intervention for divorcing mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:416–428. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Lutz MM. Intervention: Changing the nature and extent of father involvement. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. Fourth. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. pp. 446–475. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JM, Sanders MR. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral family intervention for the treatment of child behavior problems in stepfamilies. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 1999;30(34):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden T, Forgatch MS, Askeland E, Patterson GR, Bullock BM. Implementation of Parent Management Training at the national level: The case of Norway. Journal of Social Work Practice. 2005;19:319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Dennis J, Flyr ML, Morris KL, Killian C, McDowell DJ, Wild M. Fathering and children’s peer relationships. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of the Father in Child Development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. pp. 307–340. [Google Scholar]

- Pasley K, Ihinger-Tallman M, Lofquist A. Remmarriage and stepfamilies: Making progress in understanding. In: Pasley K, Ihinger-Tallman M, editors. Stepparenting: Issues in Theory, Research, and Practice. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1994. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castilia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ. Multilevel family process models: Traits, interactions, and relationships. In: Hinde RA, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within Families: Mutual Influences. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1988. pp. 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. A Social Interactional Approach: Antisocial Boys. Vol. 4. Eugene, OR: Castilia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. The next generation of PMTO models. Behavior Therapist. 2005;28(2):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Compas B. The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. American Psychologist. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Lopez E. Still looking for Pappa. American Psychologist. 2005 October;:735–736. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck J. Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. In: Lamb ME, editor. The Role of Fathers in Child Development. Third. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 66–103. [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder J, editors. Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents: A Developmental Analysis and Model for intervention. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SD. How the birth of a child affects involvement with stepchildren. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J, Crosby L, Forgatch MS, Capaldi DM. Family and peer process code: A Synthesis of Three Oregon Social Learning Center Behavior Codes (Training manual.) 1998 Available from Oregon Social Learning Center; 10Shelton McMurphey Boulevard, Eugene, OR 97401. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokur AD, van Ryn M, Gramlich EM, Price RH. Long-term follow-up and benefit-cost analysis of the Jobs Program: A preventive intervention for the unemployed. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1991;76(2):213–219. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visher JS. Stepfamilies: A work in progress. American journal of Family Therapy. 1994;22(4):337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Visher EB, Visher JS. Therapy with stepfamilies. Vol. 6. New York: Brunenr/Mazel; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich S, Hetherington EM, Vuchinich RA, Clingempeel WG. Parent - child interaction and gender differences in early adolescents’ adaptation to stepfamilies. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(4):618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Zill N. Behavior, achievement, and health problems among children in stepfamilies: Findings from a national survey of child health. In: Hetherington EM, Arastech JD, editors. Impact of Divorce, Single Parenting, and Stepparenting on Children. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 325–368. [Google Scholar]